文章信息

- 陈子玥, 蔡珊, 马宁, 张依航, 张奕, 蒋家诺, 刘云飞, 党佳佳, 钟盼亮, 师嫡, 董彦会, 朱广荣, 马军, 宋逸.

- Chen Ziyue, Cai Shan, Ma Ning, Zhang Yihang, Zhang Yi, Jiang Jianuo, Liu Yunfei, Dang Jiajia, Zhong Panliang, Shi Di, Dong Yanhui, Zhu Guangrong, Ma Jun, Song Yi

- 中国9~18岁儿童青少年心理困扰流行现状

- Prevalence of psychological distress among Chinese children and adolescents aged 9-18 years

- 中华流行病学杂志, 2023, 44(10): 1537-1544

- Chinese Journal of Epidemiology, 2023, 44(10): 1537-1544

- http://dx.doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn112338-20230517-00304

-

文章历史

收稿日期: 2023-05-17

2. 清华大学万科公共卫生与健康学院, 北京 100084

2. Vanke School of Public Health, Tsinghua University, Beijing 100084, China

心理困扰是指与正常情绪波动相关并使人感到痛苦的一系列精神和身体症状,主要包括抑郁、焦虑等[1-2]。儿童青少年是心理健康问题的重点人群,2019年WHO和联合国儿童基金会联合报告称,全球20%的青少年患有精神障碍,约一半的精神障碍始于14岁之前[3]。这一时期产生的心理健康问题不仅会延续到成年[4],还可能导致自杀、自伤、吸烟、饮酒等健康危险行为的发生风险增加[5-9],给社会和家庭带来极大负担。我国儿童青少年心理健康问题形势严峻,学龄儿童青少年精神障碍总体患病率达17.5%,抑郁障碍与焦虑障碍的患病率分别为3.0%和4.7%,与其他国家的数据相比处于较高水平[10]。但目前中国关于儿童青少年心理健康状况的全国性数据较少,现有研究存在纳入地区和样本量不足等局限性。本研究使用2019年全国学生体质与健康调研数据开展分析,旨在全面了解中国儿童青少年心理困扰流行现状,并探究其影响因素,为中国儿童青少年心理健康问题的预防和整体心理健康水平的促进提供科学依据。

对象与方法1. 研究对象:来自2019年全国学生体质与健康调研数据,该调研采用多阶段分层整群抽样的方法,根据社会经济发展水平选择高、中、低3个片区[各省(自治区、直辖市)在抽样时综合考虑地级市的区域生产总值、人均年总收入、人均食物消费量、人口自然增长率和区域社会福利指数共5项指标,在每个省内将各地级市的社会经济水平按照从高到低的顺序分为3段,每段内随机抽取1个地级市,分别定义为选择高、中、低片区]。每个片区内,分别在城市和乡村地区采用分层整群随机抽样的方法抽取调研样本,首先确定调研点校(基本与1985年第一次调研的点校相同),再以年级分层,以班级为单位,采用随机整群抽样构成调研样本。根据性别和城乡特征分为4类(每省共3个片区12类),1岁一个年龄组,每片区每类每个年龄组至少50人参与体质与健康测试,其中四年级及以上的学生在知情同意基础上进行自填式问卷调查,问卷由接受培训和考核的检测队人员在现场组织并指导学生填写。本研究对全国30个省(自治区、直辖市)(未包括西藏自治区)9~18岁儿童青少年进行分析,共选取样本176 740名,剔除社会人口学信息或心理困扰量表信息不完整的样本后共纳入有效样本148 892名。

2. 研究指标:采用凯斯勒心理困扰量表(K10)对研究对象的心理困扰进行测量。K10被认为是筛查大规模人群心理健康状况的简明、有效和可信的工具,主要对疲劳、焦虑、抑郁、不安和低价值感进行评估[11-12]。量表包括10个条目,各条目均采用Likert 5点计分(1=几乎没有,2=偶尔,3=有些时候,4=大部分时间,5=所有时间),而后将10个条目所得分值求和。K10总分≤19、20~、25~、≥30分别表示无、轻度、中度、重度心理困扰,中度和重度心理困扰合称高心理困扰[13]。本研究中,K10评分的Cronbach's α系数为0.949,探索性因子分析结果显示,KMO值为0.959,共提取1个公因子(特征值> 1),解释总方差的68.515%,各条目因子负荷为0.613~0.750。

通过2019年全国学生体质与健康调研问卷调查获得研究对象的社会人口学信息,如年龄、性别、城乡、父亲文化程度以及母亲文化程度等。通过国家统计局官网(http://www.stats.gov.cn)获取2019年省级人均GDP数据,并根据五分位数将其分为5组:低(≤P20)、中低(> P20且≤P40)、中等(> P40且≤P60)、中高(> P60且≤P80)和高(> P80)水平。

3. 统计学分析:使用方差分析、t检验和χ2检验比较不同年龄、性别、城乡、人均GDP水平、父亲文化程度和母亲文化程度的儿童青少年K10评分和高心理困扰率的差异,使用方差分析和趋势χ2检验分析年龄、人均GDP水平、父亲文化程度和母亲文化程度与K10评分和高心理困扰率之间的线性趋势。使用地图展示各省份儿童青少年K10评分和高心理困扰流行情况,使用百分比堆积条形图展示不同程度心理困扰分年龄流行情况以及K10评分各条目选项分布情况。使用趋势χ2检验分析总体和各组不同程度心理困扰率随年龄变化的线性趋势。

logistic回归常用于分析暴露因素与二元结局的关系,但当结局事件常见时,其给出的OR值往往会高估RR值,这时可以使用log-binomial回归或修正的泊松回归模型进行估计[14]。泊松回归模型常用于结局为罕见事件的前瞻性研究,本研究为横断面研究,高心理困扰率遵循二项分布,在使用泊松回归时系数的方差往往被高估、得出较宽的置信区间。因此有学者提出可以在泊松回归中使用修正的方差估计方法(Huber的三明治估计法)改善这个问题[15]。由于本研究高心理困扰率 > 10%,故使用修正泊松回归模型分析高心理困扰的影响因素。除地图和百分比堆积条形图使用R 4.2.2软件外,其余分析均使用SPSS 26.0软件完成。双侧检验,检验水准α=0.05。

结果1. 一般情况:共纳入9~12岁儿童56 485名(37.9%),13~15岁青少年46 468名(31.2%),16~18岁青少年45 939名(30.9%);男生74 309名(49.9%),女生74 583名(50.1%);城市儿童青少年75 321名(50.6%),乡村儿童青少年73 571名(49.4%)。

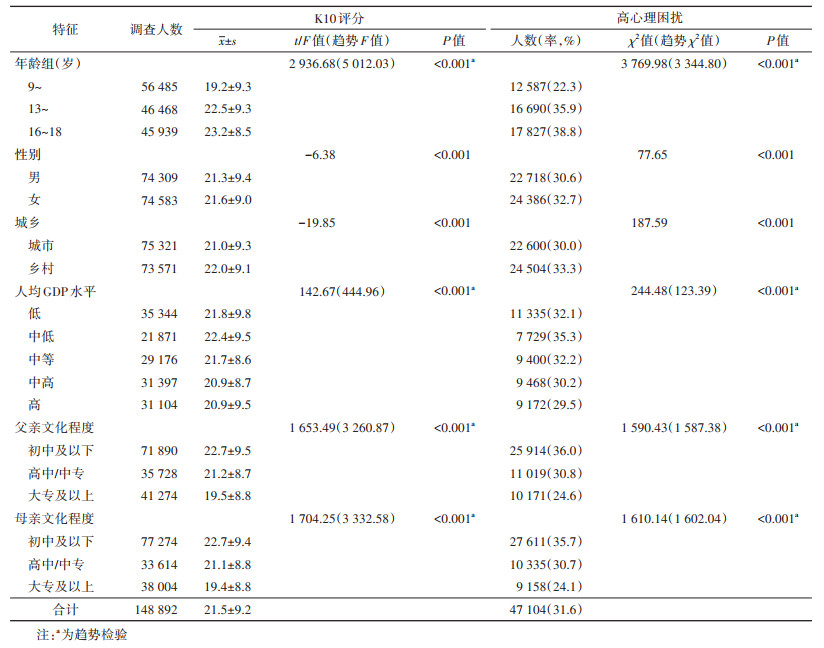

2. 儿童青少年K10评分和高心理困扰流行情况:2019年中国9~18岁儿童青少年K10评分为21.5±9.2,高心理困扰率为31.6%。9~、13~、16~18岁儿童青少年的高心理困扰率分别为22.3%、35.9%和38.8%,男生和女生的高心理困扰率分别为30.6%和32.7%,城市和乡村儿童青少年的高心理困扰率分别为30.0%和33.3%。在不同特征的调查对象中,年龄较高、女生、乡村、中低人均GDP水平地区、父/母文化程度较低的儿童青少年高心理困扰率更高(均P < 0.001)。随着年龄升高、父/母亲文化程度较低,儿童青少年K10评分和高心理困扰率均呈现上升趋势(趋势检验均P < 0.001);随着人均GDP水平降低,儿童青少年K10评分和高心理困扰率总体呈现上升趋势(趋势检验均P < 0.001)。见表 1。

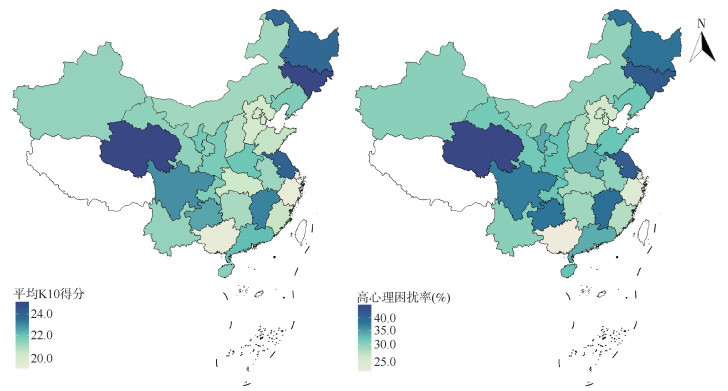

在各调查省份中,平均K10评分较低的为上海(19.2)和浙江(19.3),较高的为青海/吉林(均为25.2)和江苏(24.1);高心理困扰率较低的为广西(22.5%)和上海(23.8%),较高的为青海(46.0%)和吉林(42.0%)。见图 1。

|

| 注:审图号:GS(2019)1822号;由于西藏自治区仅调查了藏族儿童,而本研究分析汉族儿童心理困扰情况,因此西藏自治区未纳入分析 图 1 2019年中国各省份9~18岁儿童青少年K10评分和高心理困扰率 |

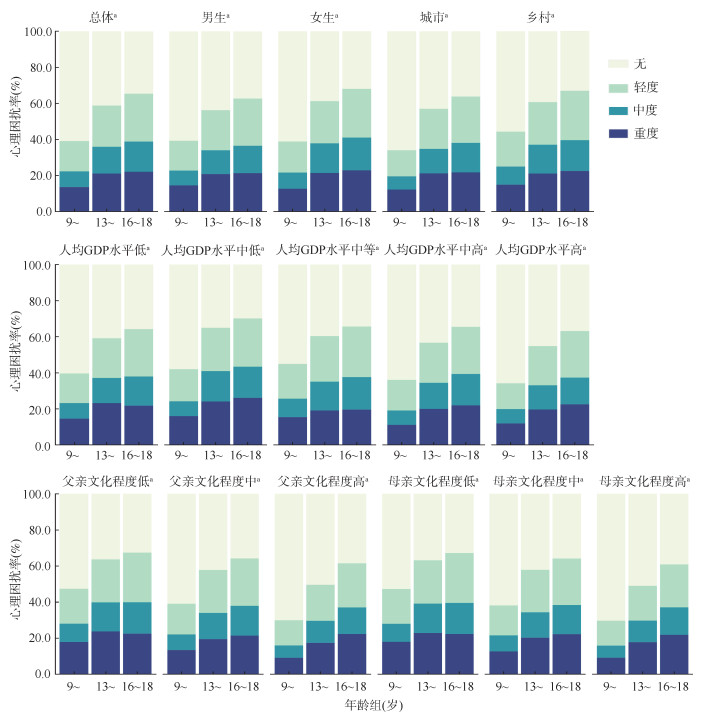

3. 儿童青少年不同程度心理困扰流行情况及年龄趋势:在不同特征的调查对象中,轻度、中度和重度心理困扰率也随年龄升高而总体呈现上升趋势(趋势检验均P < 0.001)。见图 2。

|

| 注:a趋势检验:P < 0.001;文化程度低、中、高分别代表初中及以下、高中/中专、大专及以上 图 2 2019年中国9~18岁儿童青少年不同程度心理困扰分年龄流行情况 |

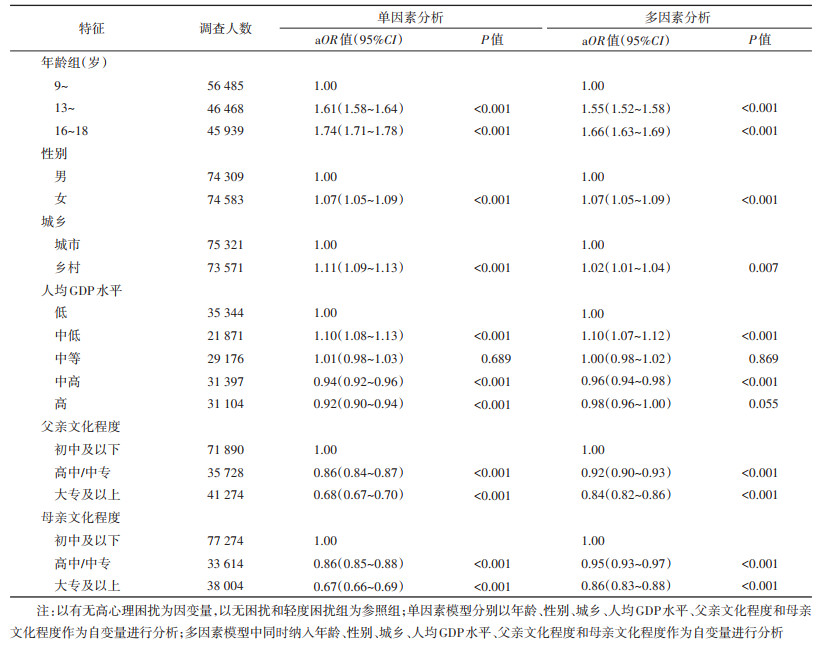

4. 2019年中国9~18岁儿童青少年高心理困扰的影响因素:单因素修正泊松回归分析结果显示,年龄较大、女生、乡村、中低人均GDP水平地区的儿童青少年高心理困扰风险更高(均P < 0.001),中高及高人均GDP水平地区、父/母亲文化程度较高的儿童青少年高心理困扰风险更低(均P < 0.001)。多因素修正泊松回归分析结果显示,13~15岁、16~18岁、女生、乡村和中低人均GDP水平地区的儿童青少年高心理困扰风险较高(均P < 0.05),其aOR值(95%CI)分别为1.55(1.52~1.58)、1.66(1.63~1.69)、1.07(1.05~1.09)、1.02(1.01~1.04)、1.10(1.07~1.12);中高人均GDP水平地区、父亲文化程度为高中/中专、大专及以上以及母亲文化程度为高中/中专、大专及以上的儿童青少年高心理困扰风险较低(均P < 0.05),其aOR值(95%CI)分别为0.96(0.94~0.98)、0.92(0.90~0.93)、0.84(0.82~0.86)、0.95(0.93~0.97)、0.86(0.83~0.88)。见表 2。

目前,中国儿童青少年心理问题形势严峻且存在上升趋势。本研究结果显示,2019年中国超过一半的9~18岁儿童青少年有不同程度的心理困扰;高心理困扰率为31.6%,高于印度12~19岁(10.3%)、澳大利亚11~17岁(21.7%)和中国香港地区12~19岁(31.3%)儿童青少年的调查结果[16-18]。对本研究人群中中国黑龙江省13~18岁青少年使用相同标准(K10≥22)计算后的心理困扰率(48.5%),显著高于2009年水平(40.1%)。在其他相关研究中也观察到了类似的上升趋势,我国儿童青少年抑郁患病率估计值由2000年之前的18.4%增长为2016年之后的26.3%[19];中国湖南省儿童青少年精神障碍总体患病率由1990年的14.9%增长为2005年的16.22%和2015年的18.2%[10, 20]。近年来,我国政府出台了多项针对儿童青少年心理健康的行动方案与工作计划,提出了减缓心理相关疾病上升趋势的行动目标[21-24]。应进一步落实相关文件的要求,并依据我国儿童青少年心理健康状况的特点和影响因素制定更具有针对性的举措,以切实达成这一行动目标。

研究发现,中国9~18岁儿童青少年心理困扰的流行情况具有以下特点:①随年龄升高的增长趋势显著;②女性和父母文化程度较低的儿童青少年心理困扰更加严重;③存在地区差异,乡村地区和中低人均GDP水平省份的儿童青少年心理困扰更加严重,城市地区和中高及高人均GDP水平省份的儿童青少年心理困扰程度较低。国内外其他研究也报告了心理问题随年龄升高而增长的趋势[25-27]。这一趋势可能与多巴胺能奖励系统和前额叶皮层的变化有关,其导致青少年较儿童时期的神经认知和奖励系统更敏感和脆弱[28]。此外,随着年龄增加,高年级学生也会面对更多来自学校、家庭和同伴的压力[29]。与本研究结果类似,在英国和澳大利亚青少年中,女生的心理困扰率也明显高于男生[17, 30]。一篇有关神经发育与社会认知的综述表明,女性进入青春期较早,且这一时期的大脑和认知发育更易受多种生理和社会因素的影响,因而更易产生抑郁、焦虑等情绪[31]。父母文化程度对儿童青少年心理健康的影响也已在多项研究中被证实[32-34],文化程度较高的父母更少使用强硬的养育策略、更多反思自身的行为,能为孩子营造更好的成长氛围[35]。本研究发现,乡村和经济发展较差地区的儿童青少年心理健康状况总体较差,这与国内其他相关研究结论一致[10, 26, 36]。但随着人均GDP升高,各省份的心理困扰率先上升后下降,且存在人均GDP高的省份儿童青少年心理困扰水平较高的情况,这可能是因为一方面乡村和经济发展较差地区获得心理健康服务较难,且存在“留守”现象导致的父母陪伴缺失[37];另一方面,经济较发达地区的父母工作压力与同伴竞争压力较大,也可能对孩子的心理健康造成不利影响[25]。

在本研究中,2019年中国9~18岁儿童青少年高心理困扰的影响因素包括年龄、性别、城乡、地区经济状况及父母文化程度,其中年龄对心理困扰的影响最强。这提示在心理健康监测与干预中,需重点关注这些高心理困扰风险的儿童青少年,及时识别他们的心理问题,并向其提供适宜的心理卫生服务。同时,可以通过针对高年级学生开设更加丰富的心理健康课程、加强乡村和欠发达地区的心理健康服务体系建设、加大对文化程度较低父母的心理健康知识宣传力度等方式有针对性地开展干预。除了社会人口学因素,相关研究还发现,个人层面的因素如睡眠或运动不足、过度使用互联网、低意义感、高空虚感,家庭层面的因素如多子女家庭、父母离世或离异、父母关系不良,学校层面的因素如同伴关系差、作业量增加等均为儿童青少年心理困扰的危险因素[14, 22, 24, 27, 32]。未来的研究应进一步探究儿童青少年心理困扰与不同因素间的关联与可能机制,为制定更高效精准的心理预防与干预措施提供依据。

本研究使用全国学生体质与健康调研数据,是样本量大、覆盖地区广的儿童青少年心理健康状况研究。研究描述了儿童青少年心理困扰的流行情况与流行特点,揭示了心理困扰的高危人群,为相关政策的制定与完善及后续研究的开展提供了线索。本研究存在局限性。第一,本研究为横断面调查,无法确定因果关联;第二,仅使用K10进行心理困扰评价,可能高估儿童青少年的心理健康问题;第三,仅纳入了社会人口学因素,未涉及其他可能与心理困扰相关的因素;第四,样本人群女性比例为50.1%,高于2019年全国10~19岁人群中女性的比例(44.18%)[38],由于研究显示女性心理困扰更加严重,因此研究可能高估我国该年龄段人口心理困扰的情况;第五,仅纳入了在校儿童青少年进行分析,但是根据教育部公布的《2019年全国教育事业发展统计公报》数据,截至2019年底中国小学阶段净入学率、初中阶段毛入学率和高中阶段毛入学率分别达99.94%、102.6%和89.5%[39],因此研究所使用的在校儿童青少年的数据很大程度上可以代表中国9~18岁儿童青少年的情况。

利益冲突 所有作者声明无利益冲突

作者贡献声明 陈子玥:统计分析、撰写论文;蔡珊、马宁:论文审阅、写作指导;张依航、张奕、蒋家诺、刘云飞、党佳佳、钟盼亮、师嫡:论文审阅;董彦会、朱广荣:采集数据、论文审阅、研究指导;马军:研究设计、论文审阅、行政/技术/材料支持、研究指导;宋逸:研究设计、论文审阅、经费支持

| [1] |

American Psychological Association. APA dictionary of psychology[EB/OL]. [2023-05-08]. https://dictionary.apa.org/psychological-distress.

|

| [2] |

Brooks RT, Beard J, Steel Z. Factor structure and interpretation of the K10[J]. Psychol Assess, 2006, 18(1): 62-70. DOI:10.1037/1040-3590.18.1.62 |

| [3] |

WHO, UNICEF. Increase in child and adolescent mental disorders spurs new push for action by UNICEF and WHO[EB/OL]. (2019-11-05)[2023-05-08]. https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/increase-child-and-adolescent-mental-disorders-spurs-new-push-action-unicef-and-who.

|

| [4] |

Roza SJ, Hofstra MB, van der Ende J, et al. Stable prediction of mood and anxiety disorders based on behavioral and emotional problems in childhood: A 14-year follow-up during childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood[J]. Am J Psychiatry, 2003, 160(12): 2116-2121. DOI:10.1176/appi.ajp.160.12.2116 |

| [5] |

Gili M, Castellví P, Vives M, et al. Mental disorders as risk factors for suicidal behavior in young people: A meta-analysis and systematic review of longitudinal studies[J]. J Affect Disord, 2019, 245: 152-162. DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2018.10.115 |

| [6] |

Nock MK, Green JG, Hwang I, et al. Prevalence, correlates, and treatment of lifetime suicidal behavior among adolescents: results from the national comorbidity survey replication adolescent supplement[J]. JAMA Psychiatry, 2013, 70(3): 300-310. DOI:10.1001/2013.jamapsychiatry.55 |

| [7] |

Portzky G, van Heeringen K. Deliberate self-harm in adolescents[J]. Curr Opin Psychiatry, 2007, 20(4): 337-342. DOI:10.1097/YCO.0b013e3281c49ff1 |

| [8] |

Guo L, Hong LY, Gao X, et al. Associations between depression risk, bullying and current smoking among Chinese adolescents: Modulated by gender[J]. Psychiatry Res, 2016, 237: 282-289. DOI:10.1016/j.psychres.2016.01.027 |

| [9] |

Tembo C, Burns S, Kalembo F. The association between levels of alcohol consumption and mental health problems and academic performance among young university students[J]. PLoS One, 2017, 12(6): e0178142. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0178142 |

| [10] |

Li FH, Cui YH, Li Y, et al. Prevalence of mental disorders in school children and adolescents in China: diagnostic data from detailed clinical assessments of 17, 524 individuals[J]. J Child Psychol Psychiatry, 2022, 63(1): 34-46. DOI:10.1111/jcpp.13445 |

| [11] |

周成超, 楚洁, 王婷, 等. 简易心理状况评定量表Kessler10中文版的信度和效度评价[J]. 中国临床心理学杂志, 2008, 16(6): 627-629. Zhou CC, Chu J, Wang T, et al. Reliability and validity of 10-item Kessler Scale (K10) Chinese version in evaluation of mental health status of Chinese population[J]. Chin J Clin Psychol, 2008, 16(6): 627-629. |

| [12] |

Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, et al. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress[J]. Psychol Med, 2002, 32(6): 959-976. DOI:10.1017/S0033291702006074 |

| [13] |

Huang JP, Xia W, Sun CH, et al. Psychological distress and its correlates in Chinese adolescents[J]. Aust N Z J Psychiatry, 2009, 43(7): 674-681. DOI:10.1080/00048670902970817 |

| [14] |

Chen WS, Qian L, Shi JX, et al. Comparing performance between log-binomial and robust Poisson regression models for estimating risk ratios under model misspecification[J]. BMC Med Res Methodol, 2018, 18(1): 63. DOI:10.1186/s12874-018-0519-5 |

| [15] |

Barros AJ, Hirakata VN. Alternatives for logistic regression in cross-sectional studies: an empirical comparison of models that directly estimate the prevalence ratio[J]. BMC Med Res Methodol, 2003, 3: 21. DOI:10.1186/1471-2288-3-21 |

| [16] |

TS J, Rani A, Menon PG, et al. Psychological distress among college students in Kerala, India—Prevalence and correlates[J]. Asian J Psychiatr, 2017, 28: 28-31. DOI:10.1016/j.ajp.2017.03.026 |

| [17] |

Hoare E, Milton K, Foster C, et al. Depression, psychological distress and Internet use among community-based Australian adolescents: a cross-sectional study[J]. BMC Public Health, 2017, 17(1): 365. DOI:10.1186/s12889-017-4272-1 |

| [18] |

Chan SM, Fung TCT. Reliability and validity of K10 and K6 in screening depressive symptoms in Hong Kong adolescents[J]. Vulnerable Child Youth Stud, 2014, 9(1): 75-85. DOI:10.1080/17450128.2013.861620 |

| [19] |

Li JY, Li J, Liang JH, et al. Depressive symptoms among children and adolescents in China: A systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Med Sci Monit, 2019, 25: 7459-7470. DOI:10.12659/MSM.916774 |

| [20] |

管冰清, 罗学荣, 邓云龙, 等. 湖南省中小学生精神障碍患病率调查[J]. 中国当代儿科杂志, 2010, 12(2): 123-127. Guan BQ, Luo XR, Deng YL, et al. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in primary and middle school students in Hunan province[J]. Chin J Contemp Pediatr, 2010, 12(2): 123-127. |

| [21] |

健康中国行动推进委员会. 健康中国行动(2019-2030年)[EB/OL]. (2019-07-09)[2023-05-11]. http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2019-07/15/content_5409694.htm?msclkid=3af03936b25c11ecb5543b1f15c25507.

|

| [22] |

中华人民共和国国务院办公厅. 国务院办公厅关于印发"十四五"国民健康规划的通知[EB/OL]. (2022-04-27)[2023-05-11]. http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2022-05/20/content_5691424.htm.

|

| [23] |

中华人民共和国国家卫生健康委员会, 中央精神文明建设指导委员会, 中华人民共和国教育部, 等. 关于印发健康中国行动——儿童青少年心理健康行动方案(2019-2022年)的通知[EB/OL]. (2019-12-27)[2023-05-11]. http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2019-12/27/content_5464437.htm.

|

| [24] |

中华人民共和国教育部, 中华人民共和国最高人民检察院, 中国共产党中央委员会宣传部, 等. 教育部等十七部门关于印发«全面加强和改进新时代学生心理健康工作专项行动计划(2023-2025年)»的通知[EB/OL]. (2023-04-27)[2023-05-11]. http://www.moe.gov.cn/srcsite/A17/moe_943/moe_946/202305/t20230511_1059219.html.

|

| [25] |

Pengpid S, Peltzer K. Prevalence and associated factors of psychological distress among a national sample of in-school adolescents in Morocco[J]. BMC Psychiatry, 2020, 20(1): 475. DOI:10.1186/s12888-020-02888-3 |

| [26] |

傅小兰, 张侃. 中国国民心理健康发展报告(2021~2022)[M]. 北京: 社会科学文献出版社, 2023. Fu XL, Zhang K. Report on national mental health development in China (2021-2022)[M]. Beijing: Social Sciences Academic Press, 2023. |

| [27] |

Qi H, Liu R, Chen X, et al. Prevalence of anxiety and associated factors for Chinese adolescents during the COVID-19 outbreak[J]. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci, 2020, 74(10): 555-557. DOI:10.1111/pcn.13102 |

| [28] |

Davey CG, Yücel M, Allen NB. The emergence of depression in adolescence: Development of the prefrontal cortex and the representation of reward[J]. Neurosci Biobehav Rev, 2008, 32(1): 1-19. DOI:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2007.04.016 |

| [29] |

Bluth K, Campo RA, Futch WS, et al. Age and gender differences in the associations of self-compassion and emotional well-being in A large adolescent sample[J]. J Youth Adolesc, 2017, 46(4): 840-853. DOI:10.1007/s10964-016-0567-2 |

| [30] |

Patalay P, Fitzsimons E. Psychological distress, self-harm and attempted suicide in UK 17-year olds: prevalence and sociodemographic inequalities[J]. Br J Psychiatry, 2021, 219(2): 437-439. DOI:10.1192/bjp.2020.258 |

| [31] |

Pfeifer JH, Allen NB. Puberty initiates cascading relationships between neurodevelopmental, social, and internalizing processes across adolescence[J]. Biol Psychiatry, 2021, 89(2): 99-108. DOI:10.1016/j.biopsych.2020.09.002 |

| [32] |

Park AL, Fuhrer R, Quesnel-Vallée A. Parents' education and the risk of major depression in early adulthood[J]. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol, 2013, 48(11): 1829-1839. DOI:10.1007/s00127-013-0697-8 |

| [33] |

Chi XL, Becker B, Yu Q, et al. Persistence and remission of depressive symptoms and psycho-social correlates in Chinese early adolescents[J]. BMC Psychiatry, 2020, 20(1): 406. DOI:10.1186/s12888-020-02808-5 |

| [34] |

赖富治, 张碧月. 家庭氛围和父母文化程度对未成年者抑郁的影响[J]. 中国预防医学杂志, 2020, 21(8): 934-936. DOI:10.16506/j.1009-6639.2020.08.020 Lai FZ, Zhang BY. The impact of family atmosphere and parental education on depression of minors in Quanzhou[J]. Chin Prev Med, 2020, 21(8): 934-936. DOI:10.16506/j.1009-6639.2020.08.020 |

| [35] |

van Holland de Graaf J, Hoogenboom M, de Roos S, et al. Socio-demographic correlates of fathers' and mothers' parenting behaviors[J]. J Child Fam Stud, 2018, 27(7): 2315-2327. DOI:10.1007/s10826-018-1059-7 |

| [36] |

王熙, 孙莹, 安静, 等. 中国儿童青少年抑郁症状性别差异的流行病学调查[J]. 中华流行病学杂志, 2013, 34(9): 893-896. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2013.09.008 Wang X, Sun Y, An J, et al. Gender difference on depressive symptoms among Chinese children and adolescents[J]. Chin J Epidemiol, 2013, 34(9): 893-896. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2013.09.008 |

| [37] |

Zhong BL, Ding J, Chen HH, et al. Depressive disorders among children in the transforming China: an epidemiological survey of prevalence, correlates, and service use[J]. Depress Anxiety, 2013, 30(9): 881-892. DOI:10.1002/da.22109 |

| [38] |

中华人民共和国国家统计局. 中国统计年鉴: 2020[M]. 北京: 中国统计出版社, 2020. National Bureau of Statistics of the People's Republic of China. China statistical yearbook: 2020[M]. Beijing: China Statistics Press, 2020. |

| [39] |

中华人民共和国教育部. 2019年全国教育事业发展统计公报[EB/OL]. (2020-05-20)[2023-07-13]. http://www.moe.gov.cn/jyb_sjzl/sjzl_fztjgb/202005/t20200520_456751.html?from=timeline&isappinstalled=07132.htm.

|

2023, Vol. 44

2023, Vol. 44