文章信息

- 国家免疫规划技术工作组流感疫苗工作组.

- National Immunization Advisory Committee (NIAC) Technical Working Group (TWG), Influenza Vaccination TWG

- 中国流感疫苗预防接种技术指南(2023-2024)

- Technical guidelines for seasonal influenza vaccination in China (2023-2024)

- 中华流行病学杂志, 2023, 44(10): 1507-1530

- Chinese Journal of Epidemiology, 2023, 44(10): 1507-1530

- http://dx.doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn112338-20230908-00139

-

文章历史

收稿日期: 2023-09-08

流行性感冒(流感)是流感病毒引起的对人类健康危害严重的急性呼吸道传染病。流感病毒抗原性易变,传播迅速,每年可引起季节性流行,在学校、托幼机构和养老院等人群聚集的场所易发生暴发疫情。人群对流感病毒普遍易感,孕妇、婴幼儿、老年人和慢性病患者等高危人群感染流感后危害更为严重。2023年2月中旬至4月底,我国呈现一波以甲型H1N1亚型为主的流感流行季,强度略高于新冠疫情前的自然流行年份,今冬明春可能会面临新冠、流感等呼吸道传染病交互或共同流行的风险。接种流感疫苗是预防流感、降低流感相关重症和死亡负担的有效手段,可以减少流感相关疾病带来的健康危害及对医疗资源的挤兑。自2018年起,中国疾病预防控制中心在每年流感流行季之前均更新并印发当年度的《中国流感疫苗预防接种技术指南》。2022年9月以来,新的研究证据在国内外发表,新的流感疫苗在我国上市,为更好地指导我国流感预防控制和疫苗使用工作,国家免疫规划技术工作组流感疫苗工作组收集和整理国内外最新研究进展,在2022年版指南的基础上进行更新和修订,形成了《中国流感疫苗预防接种技术指南(2023-2024)》。

本指南更新的内容主要包括:第一,增加了新的研究证据,尤其是我国的研究结果,包括流感疾病负担、疫苗效果、疫苗安全性监测、疫苗预防接种成本效果等;第二,更新了一年来国家卫生健康委员会、国家疾病预防控制局发布的流感防控有关政策和措施;第三,更新了2023-2024年度国内上市使用的流感疫苗种类;第四,更新了本年度三价和四价流感疫苗组分;第五,更新了2023-2024年度的流感疫苗接种建议。

一、病原学基础、临床特点和实验室诊断流感病毒属于正粘病毒科,是单股、负链、分节段的RNA病毒。根据病毒核蛋白和基质蛋白,分为甲、乙、丙、丁(或A、B、C、D)型[1]。甲型流感病毒根据病毒表面的血凝素(HA)和神经氨酸酶(NA)的蛋白结构和基因特性,可分为多种亚型。目前发现的HA和NA分别有18个(H1~18)和11个(N1~11)亚型。甲型流感病毒宿主众多,除感染人外,在动物中广泛存在,如禽类、猪、马、海豹以及鲸鱼和水貂等。乙型流感病毒根据HA基因型分为Victoria系和Yamagata系,既往多个流行季在人群中交替流行或混合流行[2]。2020年3月至今,全球几乎未再监测到自然流行的乙型Yamagata系流感病毒株[3],引起流感季节性流行的病毒主要是甲型流感病毒中的H1N1、H3N2亚型及乙型流感病毒中的Victoria系。丙型流感病毒可感染人、狗和猪,仅导致上呼吸道感染的散发病例[4-5]。丁型流感病毒主要感染猪、牛等,尚未发现感染人[6-7]。

流感感染主要以发热、头痛、肌痛和全身不适起病,体温可达39~40 ℃,可有畏寒、寒战,多伴全身肌肉关节酸痛、乏力、食欲减退等全身症状,常有咽喉痛、干咳,可有鼻塞、流涕、胸骨后不适,颜面潮红,眼结膜充血等。部分患者症状轻微或无症状。儿童的发热程度通常高于成年人,患乙型流感时恶心、呕吐、腹泻等消化道症状也较成年人多见。新生儿可仅表现为嗜睡、拒奶、呼吸暂停等。无并发症者病程呈自限性,大多于发病3~5 d后发热逐渐消退,全身症状好转,但咳嗽、体力恢复常需较长时间[8]。并发症中肺炎最为常见,其中继发性细菌性肺炎通常由肺炎链球菌、流感嗜血杆菌或金黄色葡萄球菌引起[9]。其他并发症有神经系统损伤、心脏损伤、肌炎和横纹肌溶解、休克等。儿童流感并发喉炎、中耳炎、支气管炎较成年人多见。流感的症状是临床常规诊断和治疗的主要依据,但由于缺乏特异性,易与普通感冒和其他上呼吸道感染相混淆[10]。流感确诊有赖于实验室诊断,检测方法包括病毒核酸检测、病毒分离培养、抗原检测和血清学检测[11]。

二、流行病学 (一) 传染源、传播方式、易感人群流感患者和无症状感染者是季节性流感的主要传染源。流感病毒主要通过感染者打喷嚏和咳嗽等产生的呼吸道飞沫传播,也可经口腔、鼻腔、眼睛等黏膜直接或间接接触感染。在特定场所,如人群密集且密闭或通风不良的房间内,也可能通过气溶胶的形式传播[12]。由于流感病毒易发生变异,每年流感流行株可能发生变化,导致之前通过自然感染或者免疫接种形成的抗体难以有效中和新的流行株,因此人群普遍易感。儿童由于免疫系统发育尚不完善,罹患流感风险更高。

(二) 流感在我国的流行特点和季节性流感在温带地区表现为每年冬春季的季节性流行和高发[13-14]。热带地区尤其在亚洲,流感的季节性呈高度多样化,既有半年或全年周期性流行,也有全年循环流行[15-16]。

我国南北方地区一般会在冬春季出现季节性流感高发流行,南方地区往往还会在夏季出现高发流行,既往引起夏季流行的主要为A(H3N2)亚型季节性流感病毒[2]。对我国2011-2019年度乙型流感流行特征进行的分析显示,我国乙型流感的流行强度低于甲型[17];但在部分地区和部分年份,乙型流感的流行强度高于甲型,且2020年之前,B(Yamagata)系和B(Victoria)系交替为优势株,以冬春季流行为主,不同系的流行强度在各年度间存在差异。

新冠大流行对流感活动造成了一定影响。自2020年3月开始,流感在我国呈极低流行水平;南方省份从2020年底至2021年9月流感活动呈缓慢升高,北方省份仅2021年3-5月有短期低水平流行;自2021年10月左右,南北方省份开始进入秋冬高发季节,并在2022年初达到冬季峰值,2022年3月逐步回落至低水平,以B(Victoria)系为主[18]。2022年5月开始,我国南方省份流感活动再次呈持续升高趋势,进入夏季高发期,达到近5年同期最高水平,以A(H3N2)亚型为绝对优势株;同期北方省份流感活动处于低水平,夏季高发期后,流感活动处于流行间期水平。直至2023年2月中旬至4月底,我国呈现一波以甲型H1N1亚型为主的流感流行季,强度略高于新冠疫情前的自然流行年份,但仍为季节性流行水平,较既往冬春流感季滞后约2个月,存在先北后南的地区差异。5月以来,我国南北方省份流感活动持续降低,未出现南方省份夏季流感高发[19]。

(三) 疾病负担1. 健康负担:流感与其他呼吸道传染病的共同感染可能会加重疾病带来的影响。英国一项研究评估了新冠病毒与流感、呼吸道合胞病毒(RSV)以及腺病毒等呼吸道病毒合并感染的临床结局,通过对6 965名新冠患者进行呼吸道多病原检测发现,8.4%的患者具有多病原感染,与单纯新冠病毒感染相比,新冠病毒合并流感病毒感染的住院患者,机械通气风险增加4.14(95%CI:2.00~8.49)倍,院内死亡的风险增加2.35(95%CI:1.07~5.12)倍,而合并感染RSV或腺病毒并未发现相应风险的增高[20]。

(1)全人群:据WHO估计,流感在全球每年可导致300万~500万的重症和29万~65万呼吸道疾病相关死亡[21]。人群对流感病毒普遍易感,儿童罹患率高于成年人。一项对全球32个流感疫苗接种随机对照试验(RCT)中未接种疫苗人群的流感罹患率统计,各年龄组感染率(包括有症状流感和无症状感染)分别为:儿童(<18岁)22.5%(95%CI:9.0%~46.0%)、成年人(18~64岁)10.7%(95%CI:4.5%~23.2%)、老年人(≥65岁)8.8%(95%CI:7.0%~10.8%)[22]。

一项研究通过系统文献检索获得有关参数来估算中国2006-2019年间流感相关健康负担,结果显示:我国每年流感导致的流感样病例(ILI)超额门急诊就诊例数平均为300.5万(95%CI:216.5万~391.2万),严重急性呼吸道感染(SARI)住院病例数平均为234.6万(95%CI:185.7万~288.7万),呼吸系统疾病超额死亡例数平均为9.2万(95%CI:7.5万~11.2万)[23]。一项研究基于全国流感监测和死因监测数据使用线性回归模型估计流感相关超额呼吸系统疾病死亡,发现2010-2011至2014-2015流行季,全国平均每年有8.8万(95%CI:8.4万~9.2万)例流感相关呼吸系统疾病超额死亡,其中≥60岁老年人的流感相关超额死亡数占全人群的80%,其超额死亡率显著高于<60岁人群(38.5/10万人年vs. 1.5/10万人年)[24]。

(2)慢性基础性疾病患者:与同龄健康人相比,慢性基础性疾病患者感染流感后,更易发展为重症甚至死亡,其流感相关住院率和超额死亡率更高。一项研究基于全球流感住院监测网络数据分析发现,2017-2018流行季,10.6%的流感相关住院病例出现严重临床结局,如需要机械通气、收住ICU或死亡等,患有慢性阻塞性肺疾病(COPD)和糖尿病等慢性基础性疾病者出现上述严重临床结局的风险更高[25]。2018-2019流行季,美国一项针对患有慢性基础性疾病儿童流感相关住院的回顾性研究发现,罹患至少一种基础性疾病的儿童的住院风险高出健康儿童数倍(OR=6.84,95%CI:3.78~12.37),且不同基础性疾病儿童患者住院风险也有差异,患有内分泌或代谢性疾病的儿童入院治疗风险是健康儿童的8.23(95%CI:4.42~15.32)倍,患有神经系统疾病的儿童的入院风险为6.35(95%CI:3.60~11.24)倍[26]。

(3)孕妇:在不同国家、不同时间开展的观察性研究发现,妇女在妊娠期间感染流感常见,且比产后发病率更高。我国苏州市18 724名年龄中位数为28岁的孕妇队列观察显示,2015-2018三个流行季流感发病率分别为0.7/100人月、1.0/100人月、2.1/100人月[27-28]。肯尼亚某地区在2015年6月至2020年5月期间连续纳入3 026名孕妇前瞻性观察妊娠期间和产后的流感发病情况,结果显示,妊娠期间孕妇实验室确诊流感发病率为10.3次/1 000人月(95%CI:8.6~11.8),是产后的2.6倍(4.0次/1 000人月,95%CI:2.6~5.5),感染HIV的孕妇妊娠期间发病率则更高(15.6次/1 000人月,95%CI:11.0~20.6)[29]。

妊娠后机体会出现免疫和生理上的变化[30-31],可能导致罹患流感时严重程度增加[32],住院、严重疾病和死亡风险增高,并增加死产风险[33]。2019年一项纳入了33个队列或病例对照研究的超过3万名感染流感的育龄女性个案数据的Meta分析发现,感染流感后孕妇的住院风险是非孕妇的6.80(95%CI:6.02~7.68)倍[34]。另有一项研究利用2000-2018年的美国全国住院患者样本对分娩住院情况进行了重复横断面分析,发现在分娩住院时确诊感染流感的产妇相较于未感染者出现严重并发症的风险更高(OR=2.24,95%CI:2.17~2.31)[35]。我国对2009年流感大流行期间住院病例的研究发现,因感染A(H1N1)pdm09亚型流感死亡的育龄女性中20%为孕妇(孕妇仅占育龄妇女人口数的3%);与未妊娠的健康育龄女性相比,孕妇出现严重疾病的风险增加3.3(95%CI:2.7~4.0)倍,孕中期(OR=6.10,95%CI:3.12~19.94)和孕晚期(OR=7.62,95%CI:3.99~14.55)出现严重疾病的风险进一步增加[36]。北京大学一项系统综述纳入了截至2020年11月的17项队列研究,目标人群超过200万,发现妊娠期间感染流感增加死产风险(RR=3.62,95%CI:1.60~8.20),但对早产、胎儿死亡、小于胎龄儿、低出生体重未见影响[33]。

(4)儿童:在不同国家进行的以家庭和社区为基础的研究表明,流感发病率在儿童中最高,并随着年龄的增长而下降,约20%~40%有症状的儿童可出现流感样症状(发热、伴咳嗽或咽痛),无症状的比例可达14%到50%以上不等[10]。我国北方2018-2019流行季儿童和成年人流感感染率的研究发现,儿童季节性流感总体感染率(31%)和A(H3N2)亚型感染率(17%)均显著高于成年人感染率(21%和10%)[37]。上海市一项基于流感监测数据的贝叶斯模型估计流感疾病负担的研究显示,2010-2017年间,0~14岁儿童平均每年流感相关ILI门诊超额就诊率最高(1 430.9/10万,95%CI:1 096.9/10万~1 773.4/10万),15~64岁成年人以及≥65岁老年人分别为781.9/10万(95%CI:664.7/10万~894.8/10万)和1 096.8/10万(95%CI:914.3/10万~1 261.6/10万)[38]。

<5岁儿童感染流感易出现重症,可导致死亡,患基础性疾病的儿童死亡风险显著高于健康儿童,但也有将近半数的死亡病例发生在健康儿童[39]。一项对全球<5岁儿童开展的流感相关呼吸系统感染疾病负担系统综述模型研究提示:2018年全球<5岁儿童约有1 010万[不确定区间(UR):680万~1 510万]流感相关急性下呼吸道感染(ALRI),87万(UR:54.3万~141.5万)流感相关ALRI住院病例,3.48万(UR:1.32万~9.72万)流感相关ALRI病例死亡[40]。一项对全球流感相关死亡的模型研究,纳入的92个国家每年约有9 243~105 690名<5岁儿童死于流感相关呼吸系统疾病[21]。

(5)学生:学校作为相对封闭的人群密集场所,容易发生流感病毒的传播[41-42],导致学龄儿童与其他人群相比流感感染率更高[43]。学龄儿童在学校、家庭和社区的流感传播中发挥重要的作用,流感流行可引起大量学龄儿童缺课和父母缺勤[44-45]。学校的流感疫情暴发往往早于社区,并加剧流感在社区的传播[46]。我国每年报告的流感暴发疫情中,90%以上发生在学校和托幼机构,如2019-2020流行季各类型学校和托幼机构报告ILI(含流感)暴发疫情占全年度暴发疫情的98.5%[47]。

(6)医务人员:由于其工作环境的特殊性,相较于普通人群,医务人员具有更高的流感感染风险[48]。一项在2009年流感大流行期间对医务人员感染A(H1N1)pdm09亚型流感的风险进行的系统综述和Meta分析显示,医务人员的感染风险明显高于普通人群(OR=2.08,95%CI:1.73~2.51)[49]。医务人员感染流感可导致缺勤率升高,造成医疗服务中断[50]。美国一项研究显示,罹患流感样症状的医护人员出勤率为92%[51],感染流感的医务人员可能进一步将流感传染给患者[52],使其面临严重疾病、并发症和死亡的高风险[53-54]。

(7)老年人:老年人感染流感可导致相当高的住院负担。北京市基于SARI监测的研究显示,≥60岁老年人在2014-2016两个流行季中流感相关SARI住院率分别为105/10万(95%CI:85/10万~129/10万)和66/10万(95%CI:50/10万~86/10万),远高于25~59岁成年人(分别为10/10万和4/10万)和15~24岁青少年(分别为2/10万和0/10万)[55]。在2010-2012流行季荆州市基于人群的SARI监测发现,≥65岁老年人中确诊流感导致的SARI病例住院率为89/10万~141/10万[56]。

老年人罹患流感后易出现严重并发症,面临较高的重症和死亡风险。一项纳入全球多个国家的系统综述表明,流感相关的住院风险随年龄的增长而增加,尤其对于长期居住在护理机构≥65岁、有基础性疾病的老年人;A(H3N2)亚型毒株为主的流行季,≥65岁老年人流感相关的住院、ICU收治和死亡的风险更高[57]。研究显示,我国≥65岁老年人流感相关的呼吸和循环系统疾病、全死因超额死亡率分别为64/10万~147/10万、75/10万~186/10万[58-60],与新加坡[59, 61]、葡萄牙[62]、美国[63]等国家接近。

与其他年龄组相比,流感相关死亡风险在老年人中最高,且随着年龄增长而增加。一项关于全球流感超额死亡率的模型研究表明,<60岁人群中因流感相关呼吸道超额死亡率为0.1/10万~6.4/10万,65~74岁人群超额死亡率为2.9/10万~44.0/10万,≥75岁人群为17.9/10万~223.5/10万[21]。≥65岁老年人流感相关超额死亡率远高于0~64岁组,80%~95%的流感相关超额死亡发生在≥65岁老年人[24, 58-60, 64]。

除学校和托幼机构之外,养老院、福利院等老年人集体居住的机构也是易发生流感暴发疫情的重点场所[65]。

2. 经济负担和健康相关生命质量:一项研究提示,2019年全国流感相关经济负担为263.81亿元,约占当年国内生产总值的0.266%,其中住院病例、门急诊病例和早亡引起生产力损失分别占总经济负担的86.4%、11.3%和2.4%[23]。流感相关经济负担在不同人群亚组间的差异具有显著性,≥60岁老年人的直接医疗费用较高;儿童和18~60岁人群误工成本导致的间接经济负担较重[66];患有慢性基础性疾病的流感患者其门诊和住院费均高于无基础性疾病的流感患者[66-67];未接种流感疫苗的老年ILI经济负担显著高于接种者[68-69]。

在罹患流感期间,患者的健康效用值显著下降,不同亚组流感患者的生存质量也存在一定差异。与无基础性疾病的流感病例相比,有基础性疾病的门诊和住院病例的健康效用值较低(门诊:0.57 vs. 0.63,住院:0.54 vs. 0.63)[70],接种流感疫苗的病例健康效用值较高(37.73 vs. 29.55,SF-8量表测量)[71]。

(四) 流感的预防治疗措施每年接种流感疫苗是预防流感的有效手段,可以显著降低接种者罹患流感和发生严重并发症的风险。神经氨酸酶抑制剂奥司他韦、扎那米韦、帕拉米韦等和聚合酶抑制剂巴洛沙韦等是甲型和乙型流感的有效治疗药物,早期尤其是发病48 h之内应用抗流感病毒药物能显著降低流感重症和死亡的发生率。抗病毒药物应在医生的指导下使用。

采取日常防护措施也可以有效减少流感的感染和传播,包括:保持良好的呼吸道卫生习惯,咳嗽或打喷嚏时,用纸巾、毛巾等遮住口鼻;勤洗手,尽量避免触摸眼睛、鼻或口;均衡饮食,适量运动,充足休息等;避免近距离接触流感样症状患者;在流感流行季尽量减少去人群聚集场所。一旦出现流感样症状,应居家休息,进行健康观察,不带病上班、上课,接触家庭成员时戴口罩,减少疾病传播;如发现病情进行性加重,则应尽快去医院就诊,患者及陪护人员要戴口罩,避免交叉感染。

三、流感疫苗 (一) 国内外上市的流感疫苗全球已上市的流感疫苗分为流感病毒灭活疫苗、流感病毒减毒活疫苗和流感病毒重组疫苗。按照疫苗所含组分,分为三价和四价流感疫苗,其中三价流感疫苗组分含有A(H3N2)亚型、A(H1N1)pdm09亚型和B型流感病毒株的一个系;四价流感疫苗组分含A(H3N2)亚型、A(H1N1)pdm09亚型和B(Victoria)系、B(Yamagata)系。根据生产工艺,又可分为基于鸡胚培养、基于细胞培养和重组流感疫苗。

2023-2024流行季我国使用的流感疫苗包括三价灭活流感疫苗(IIV3)、四价灭活流感疫苗(IIV4)和三价减毒活疫苗(LAIV3)。IIV3和IIV4均有0.25 ml和0.5 ml两种剂型,LAIV3为0.2 ml剂型。

(二) 免疫原性、效力和效果免疫原性是指抗原能够刺激机体形成特异抗体或致敏淋巴细胞的能力,评价指标主要为病毒株特异性血凝抑制(HI)抗体滴度和血清抗体阳转率,评价结果会受接种者年龄、免疫功能和接种前抗体水平的影响。疫苗保护效力通常是指其上市前在RCT理想条件下的有效性;疫苗保护效果则指其在人群中实际应用的有效性。评价流感疫苗效力和效果的观察终点主要包括实验室确诊流感、急性呼吸道疾病或ILI就诊、流感和肺炎相关住院或死亡等。

根据公开发表的多项研究显示,我国获批上市的IIV3和IIV4接种后各疫苗株的HI抗体阳转率、HI抗体几何平均效价(GMT)平均增长倍数(GMI)和血清抗体保护率等均达到检验标准,具有较好的免疫原性和效力效果。国内关于LAIV3和适用于≥6月龄人群接种的0.5 ml剂量IIV4发表的研究较少。现结合国内外研究进展阐述流感疫苗产品在不同人群中的免疫原性、效力和效果。

1. 全人群:灭活流感疫苗(IIV)在健康成年人中免疫原性良好。一项纳入了2011-2020流行季8项国内外RCT研究的Meta分析显示,在18~64岁人群中,对于甲型流感病毒株和IIV3中包含的B系,IIV4和IIV3的血清阳转率和血清保护率的差异无统计学意义,但IIV4对IIV3中未包括的B系血清阳转率和血清保护率差异有统计学意义[72]。2018-2019流行季,河南省开展的一项四价流感亚单位疫苗的Ⅰ期RCT研究结果显示,在≥3岁年龄组四价流感亚单位疫苗免疫原性非劣效于四价流感病毒裂解疫苗[73],随后的Ⅲ期RCT研究也显示在免疫原性整体上非劣效于裂解疫苗,针对4种疫苗株诱导出更强的免疫反应,GMT均高于裂解疫苗且差异有统计学意义[A(H1N1)pdm09亚型:400.39 vs. 333.46,P<0.001;A(H3N2)亚型:436.71 vs. 384.13,P=0.004;B(Victoria)系:77.80 vs. 67.90,P=0.001;B(Yamagata)系:267.60 vs. 180.63,P<0.001][74]。

国外RCT研究系统综述和Meta分析显示,在≥18岁人群中,几乎所有类型的流感疫苗均可有效降低实验室确诊流感感染风险;而在儿童中,与IIV3相比,LAIV3和三价灭活佐剂(MF59/AS03)疫苗保护效力更好[75]。

在健康成年人中,接种IIV可预防59%(95%CI:51%~67%)的实验室确诊流感[76];当疫苗株和流行株匹配时,接种IIV可减少42%(95%CI:9%~63%)的ILI就诊[77]。在全年龄组人群中,检测阴性病例对照研究的系统综述(包含2004-2015年的56项研究)提示流感疫苗对不同型别和亚型流感的保护效果有明显差异,其中B型为54%(95%CI:46%~61%),A(H1N1)pdm09亚型为61%(95%CI:57%~65%),A(H3N2)亚型为33%(95%CI:26%~39%)[78]。2022-2023流行季,我国石河子地区一项基于全人群的检测阴性设计研究发现,接种流感疫苗对甲型流感病毒的保护效果为56.3%(95%CI:13.6%~73.6%)[79]。

2. 孕妇:研究显示,孕妇接种IIV,具有良好免疫原性[80-82]。除HIV感染孕妇的抗体反应较低、持续时间相对较短外[83],孕妇和非孕妇对流感疫苗的抗体反应类似[81, 84]。

孕妇接种流感疫苗,不仅保护孕妇自身降低孕期患流感、孕期发热、子痫前期、胎盘早破的风险,也可通过胎传抗体保护<6月龄无法接种流感疫苗的新生儿免于罹患流感[85-88]。在4项RCT研究和3项观察性研究的Meta分析中,孕期接种流感疫苗对<6月龄婴儿实验室确诊流感的保护效果为48%(95%CI:33%~59%);在4项观察性研究的Meta分析中,孕期接种流感疫苗对<6月龄婴儿实验室确诊的流感相关住院的保护效果为72%(95%CI:39%~87%)[89]。2019年一项Meta分析指出,相较于孕早期接种流感疫苗,孕晚期接种流感疫苗的孕妇及其新生儿体内HI滴度上升倍数更高,且孕晚期接种流感疫苗更有利于抗体传递给胎儿[90]。一项对孕妇接种流感疫苗的时间与婴儿出生时抗体水平的观察性研究也发现,与孕早期相比,孕妇在孕中期或孕晚期接种流感疫苗其婴儿体内的抗体滴度会更高[91]。多国的回顾性队列观察累计超过35万人,显示产前接种流感疫苗总体上可降低早产发生率(OR=0.78,95%CI:0.74~0.82)、降低出生时小于胎龄儿的发生率(OR=0.83,95%CI:079~0.87),但不同研究间结果差异较大,可能与研究对象健康选择偏倚、未调整接种和暴露时间间隔、接种时的孕期、疫苗组分与流行株匹配程度等因素有关[92]。

3. 儿童:

(1)IIV:≥6月龄儿童按推荐的免疫程序接种IIV后对流感病毒感染有保护作用。2017-2020年间在欧洲地区和亚洲地区开展的一项多中心RCT研究中,IIV4对6~35月龄儿童的实验室确诊流感的总体保护效果为54%(95%CI:37%~66%),对匹配流行株的保护效果达到68%(95%CI:45%~81%)[93]。日本2022-2023流感流行季是第一次流感和新冠共同流行,研究发现在6~12岁年龄组住院病例中接种四价流感病毒裂解疫苗对A(H1N1)pdm09亚型的保护效果为76%(95%CI:21%~92%)[94]。一项在中国浙江省永康市和义乌市开展的流感疫苗保护效果研究中,将2016-2018流行季当地监测到的6~72月龄ILI作为研究对象,发现总体流感疫苗保护效果为58%(95%CI:31%~74%)[95]。

<9岁儿童首次接种IIV3时,接种2剂次比1剂次能提供更好的保护作用。对中国香港地区2011-2019流行季因急性呼吸道感染住院的6月龄~9岁儿童开展了接种2剂次和1剂次流感疫苗效果研究,发现首次接种流感疫苗完成2剂次程序和仅接种1剂次对流感确诊住院病例的保护效果分别为73%(95%CI:69%~77%)和31%(95%CI:8%~48%)[96]。国内的相关研究也发现类似结果[97]。

6~35月龄儿童的全剂量(0.5 ml)IIV已在多个国家或地区使用[98],我国也于今年上市供应。一项在美国和墨西哥开展的针对6~35月龄儿童的Ⅲ期随机观察者盲法试验发现全剂量IIV4对两种乙型疫苗株的免疫原性均优于半剂量IIV4,可能提高低龄儿童对乙型流感的保护效力[99]。2020年在我国开展的一项多中心RCT研究发现,6~35月龄儿童中全剂量IIV4对所有抗原的免疫应答优于半剂量IIV4[100]。美国儿科学会发布的2023-2024儿童流感防控建议中提到,全剂量IIV4可应用于6月龄以上的人群[101]。

接种流感疫苗可降低儿童流感相关就诊和住院,并预防相关并发症。中国北京市对2013-2016流行季流感疫苗效果模型研究发现,对于5~14岁儿童,3个季节接种流感疫苗分别可以减少约104 000(95%CI:101 000~106 000)例、23 000(95%CI:22 000~23 000)例和21 000(95%CI:21 000~ 22 000)例流感相关门急诊就诊[102]。中国苏州市一项关于6~59月龄儿童在2011年10月至2016年9月流行季接种流感疫苗效果的研究发现,在25万名儿童中,接种流感疫苗预估将减少731(95%CI:549~960)例流感住院病例,减少10 024(95%CI:7 593~12 937)例ILI[103]。

儿童接种流感疫苗还能减少父母缺勤及对其他人群起到间接保护作用。一项针对6~35月龄儿童的多中心RCT研究显示,与安慰剂对照组相比,接种IIV4的儿童确诊流感后医疗保健行为风险减少59%(95%CI:44%~70%)、父母缺勤风险减少70%(95%CI:33%~88%)[104]。中国香港地区的一项基于家庭的RCT研究探索了儿童接种流感疫苗对于家庭成员的保护作用,发现可减少其他家庭成员约20%的感染风险[105]。

另外,接种流感疫苗还可以减少儿童抗生素的使用。一项全球开展的多中心RCT研究显示,6~35月龄儿童使用IIV4后降低了39%(95%CI:27%~56%)的抗生素使用[104]。

(2)减毒活疫苗(LAIV):LAIV中含有鼻腔接种后可在鼻咽部复制的减毒流感病毒,其所含疫苗株有3个特点:毒力衰减(限制其反应原性和致病性)、温度敏感性(限制其在下呼吸道复制)和冷适应性(允许其在鼻咽部复制)[106]。经鼻腔接种LAIV后可诱导血清和鼻黏膜均产生抗体,同时也可诱导细胞介导的免疫反应[107]。

一项关于评价LAIV预防2~17岁儿童季节性流感的保护效果的研究,对2003-2018年间的14篇相关文献进行了Meta分析,结果显示LAIV预防儿童季节性流感的保护效果为49%(95%CI:40%~57%),预防A(H1N1)pdm09亚型、A(H3N2)亚型和B型流感的保护效果分别为35%(95%CI:5%~56%)、35%(95%CI:21%~46%)和71%(95%CI:55%~82%)[108]。一项2016-2017流行季在我国东部地区3~17岁儿童中开展的RCT研究评价了LAIV3的效力,结果发现疫苗对所有亚型流感的保护效力为62.5%(95%CI:27.6%~80.6%),对A(H3N2)亚型流感的保护效力为63.3%(95%CI:27.5%~81.5%)[109]。

除对实验室确诊流感有保护效果外,一项RCT研究显示,LAIV3可减少21%(95%CI:11%~30%)的发热性疾病,也可减少30%(95%CI:18%~45%)的中耳炎[110]。对6项RCT研究的Meta分析显示,LAIV3对6~83月龄儿童实验室确诊流感合并急性中耳炎的保护效力为85%(95%CI:78%~90%)[111]。

4. 学生:开展基于学校的流感疫苗接种可有效减少学龄儿童流感感染的发生。一项纳入37项检测阴性病例对照研究的Meta分析表明,在≤17岁的儿童和青少年中,流感疫苗对减少任何亚型流感患者住院的保护效果为53.3%(95%CI:47.2%~58.8%)[112]。疫苗株与流行株匹配的季节,北京市流感疫苗大规模集中接种可使流感集中发热疫情的发生风险降低89%(OR=0.11,95%CI:0.075~0.17)[113]。在疫苗株与流行株不完全匹配的情况下,北京市流感疫苗大规模集中接种仍可使流感集中发热疫情的发生风险降低50%(RR=0.50,95%CI:0.34~0.75)[114]。2018-2019流行季,中国香港地区的一项研究发现,接种流感疫苗的小学生与未接种的小学生相比,ILI发生率显著降低(7.7% vs. 14.1%),保护效果达45.3%[115]。

学生接种流感疫苗还可减少由于罹患流感导致的缺勤缺课。深圳市2017年12月至2020年6月在286所小学开展的研究显示,相比于非入校接种和低接种率,入校接种和高接种率可有效降低缺课的发生风险,对缺课的预防效果分别为32.6%(95%CI:17.0%~45.3%)和53.0%(95%CI:42.1%~61.8%)[116]。

5. 老年人:接种流感疫苗可有效降低老年人群的流感发病。2017年一项对检测阴性病例对照研究设计的社区老年人流感疫苗效果的Meta分析发现,无论流感疫苗与流行株是否匹配,接种流感疫苗均有效,疫苗株与流行株匹配时保护效果为44.4%(95%CI:22.6%~60.0%),不匹配时保护效果为20.0%(95%CI:3.5%~33.7%)[117]。我国研究者通过构建健康大数据平台动态分析流感疫苗保护效果,发现2020-2021流行季宁波市鄞州区接种流感疫苗对≥70岁老年人群门急诊ILI的保护效果为32.37%(95%CI:19.24%~43.37%)[118]。

接种流感疫苗还可降低老年人流感相关并发症发生率,减少流感相关住院及死亡。2013年一篇对95项研究的Meta分析发现,在流感季节,老年人接种流感疫苗可预防28%(95%CI:26%~30%)的流感相关并发症、39%(95%CI:35%~43%)的流感样症状以及49%(95%CI:33%~62%)的确诊流感[119]。2010-2016连续6个流行季,加拿大安大略省一项检测阴性病例对照研究表明,接种流感疫苗对≥65岁老年人流感病毒感染死亡的总保护效果为20%(95%CI:7%~30%)[120]。南半球智利、巴拉圭和乌拉圭的一项研究收集了2022年3-11月在18个哨点医院住院SARI病例的监测数据,分析发现接种流感疫苗对≥60岁老年人实验室确诊流感的保护效果为32%(95%CI:2%~52%),保护效果下降主要由于在2022年8-11月经历了第二波的A(H3N2)亚型和B型流感的流行[121]。

多项研究表明,老年人接种标准剂量的流感疫苗所产生的免疫原性与年轻人比较相对较低[122-123]。高剂量IIV将每种抗原组分的含量由标准的15 μg提高到60 μg[124]。与接种标准剂量流感疫苗相比,老年人接种高剂量流感疫苗可产生较高水平的流感抗体[125-126],对于预防流感确诊感染具有相对较好的保护效力[127-128],同时对于预防流感确诊感染、流感相关就诊、住院和死亡具有相对较好的保护效果[129-133]。除高剂量灭活疫苗外,国外还上市了佐剂疫苗、重组疫苗等,也可以给予老年人更好的保护[134-135]。

6. 慢性基础性疾病患者:流感疫苗对儿童和成年人哮喘患者有较好的免疫原性[136];哮喘患者接种流感疫苗能够有效减少流感感染和哮喘发作[137]。我国开展的队列研究表明,接种IIV3可以减少COPD和慢性支气管炎的急性感染和住院[138-139]。

冠心病患者接种流感疫苗后,可以减少急性冠脉综合征(ACS)患者的心血管不良事件发生率,降低其住院风险和与心脏病相关的死亡率[140]。近期一项系统综述纳入2000-2021年进行的6项RCT研究,发现接种流感疫苗将心血管疾病不良事件发生风险降低34%(95%CI:17%~47%),ACS发生风险降低45%(95%CI:25%~49%)[141]。流感疫苗还可降低心衰患者的死亡风险(HR=0.82,95%CI:0.81~0.84)[142]。

18~64岁的糖尿病患者接种流感疫苗对住院的保护效果为58%;老年人糖尿病患者接种流感疫苗,对住院的保护效果为23%,对全死因死亡的保护效果为38%~56%[143]。研究提示接种流感疫苗可以减少免疫功能受损的流感住院儿童并发症的发生风险,缩短住院时间[144]。

7. 医务人员:医务人员接种流感疫苗除有利于保护个人外,还有利于确保卫生系统的正常运转。一项系统综述和Meta分析研究证实,接种流感疫苗可以降低医务人员流感发病率,减少医务人员带病工作的风险,对保障医疗安全有重要意义[145]。2018-2019年一项在沙特阿拉伯王国开展的研究结果显示,接种流感疫苗对预防医务人员实验室确诊各型流感总的保护效果为42%,预防A(H3N2)亚型的保护效果为76%,预防A(H1N1)pdm09亚型流感的保护效果为55%[146]。为保护医务人员与患者,每年接种疫苗可以降低医务人员和患者流感相关疾病的发病率及其可能潜在的严重后果,减少由于流感导致的缺勤,阻断从医护人员到患者的传播,从而降低卫生系统更广泛的负担,因此应鼓励医务人员在流感季来临前接种流感疫苗[147]。

(三) 免疫持久性感染流感病毒或接种流感疫苗后获得的免疫力会随时间衰减,衰减程度与人的年龄和身体状况、疫苗抗原等因素有关。澳大利亚开展的一项流感疫苗抗体动力学研究显示,接种流感疫苗1个月后各型疫苗株诱导的抗体水平达到高峰,3个月左右后开始下降,在接种6个月后抗体水平仍高于基线,提示接种流感疫苗后抗体保护水平至少可维持6个月之久[148]。中国浙江省台州市开展一项研究也发现接种流感疫苗6个月后部分疫苗株介导的抗体水平仍较高[149]。研究显示,流感疫苗接种1年后体内血清抗体水平显著降低[150-151]。研究表明血清抗体降低与骨髓浆细胞数量下降相关,即特异性骨髓浆细胞在流感疫苗接种4周后增加,但在1年后降至接种前水平[152]。

为匹配不断变异的流感病毒,WHO在多数季节推荐的流感疫苗组分会更新一个或多个毒株,疫苗毒株与前一季节完全相同的情况也存在。为保证接种人群获得最大程度的保护,即使流感疫苗组分与前一季节完全相同,鉴于大多数接种者上一次接种产生的抗体滴度已显著下降,因此不管前一季节是否接种流感疫苗,仍建议在当年流感季节来临前接种。

疫苗效果研究同样证实了每年接种的必要性。中国香港地区对2012-2017连续五个流行季儿童住院病例中流感疫苗效果进行分析评估,发现流感疫苗接种后每个月保护效果约下降2%~5%[153]。江苏省的一项前瞻性血清流行病学研究显示,重复接种流感疫苗者体内抗体的几何平均滴度、滴度≥40的比例较单次接种者上升或与单次接种者相似,提示重复接种流感疫苗可以诱导与单次接种相似或更强的免疫保护抗体[154]。一项将疫苗接种史考虑在内用以评估疫苗效果的简单模型研究发现,之前流感季节接种过流感疫苗,即使在当季不接种的情况下仍存在一定保护作用[155]。

(四) 安全性接种流感疫苗的常见不良反应有局部反应(接种部位红晕、肿胀、硬结、疼痛、烧灼感等)和全身反应(发热、头痛、头晕、嗜睡、乏力、肌痛等)。通常是轻微的、自限的,一般在1~2 d内自行消退,极少出现重度反应。

1. IIV:通过肌内注射接种IIV是安全的,所有年龄段人群均具有良好的耐受性[77, 156-157]。研究显示,≥65岁老年人或18~64岁有一种或多种慢性疾病的住院患者在接种IIV后不良反应发生率无差别[158]。孕妇接种IIV后未见孕妇并发症、不良妊娠结局等不良反应的发生风险增加[159]。

用于≥3岁人群的四价流感亚单位流感疫苗和≥6月龄人群的全剂量(0.5 ml)四价裂解流感疫苗于2023年首次在我国上市使用。从疫苗制备工艺来看,亚单位疫苗去除病毒内部蛋白仅保留纯度较高的HA和NA抗原成分,相较于裂解疫苗具有更好的安全性[160]。亚单位疫苗的RCT研究显示,≥3岁人群接种流感亚单位疫苗报告的不良反应与裂解疫苗相比没有差异或更少[73-74, 161],四价流感亚单位疫苗与三价流感亚单位疫苗的安全性相似[162-163]。一项在河南省开展的Ⅲ期RCT研究显示,18~64岁年龄组四价流感亚单位疫苗总的不良事件发生率低于四价裂解疫苗(6.29% vs. 10.86%,P=0.031)[74]。6~35月龄儿童接种0.5 ml剂型四价裂解疫苗和0.25 ml剂型四价裂解疫苗后的安全性具有可比性[100]。

2018-2020流感季中国疑似预防接种异常反应(AEFI)信息系统的监测数据显示,接种IIV后,AEFI总报告发生率为41.04/10万,其中不良反应报告发生率为39.60/10万(一般反应和异常反应分别为37.41/10万、2.19/10万),一般反应中最多为高热(腋温≥38.6 ℃),其次为局部红肿(直径 > 2.5 cm)和局部硬结(> 2.5 cm),报告发生率分别为18.28/10万、5.95/10万和1.85/10万;非严重异常反应中,过敏性皮疹和血管性水肿报告较多,报告发生率分别为1.51/10万和0.16/10万;严重异常反应的报告发生率较低(0.29/10万),排名前两位的为热性惊厥和过敏性紫癜,报告发生率分别为0.16/万和0.07/10万[164]。热性惊厥在儿童中较为常见,2%~5%的6月龄~5岁儿童至少经历过一次热性惊厥,几乎所有出现热性惊厥的儿童均会快速康复[165],单独接种IIV未显著增加发生热性惊厥的风险[166-167]。

2. LAIV:LAIV在健康儿童和成年人中的安全性良好,具有良好的耐受性。一项系统综述显示,与接种安慰剂或IIV相比,接种LAIV后自限性的流鼻涕或鼻塞、咽痛、发热等症状的发生更常见[168]。一项针对2~17岁儿童青少年接种LAIV3疫苗安全性的大型队列研究发现,接种LAIV后不良反应的风险没有显著增加,仅观察到1例与接种LAIV相关的过敏反应(发生率为1.7/100万)和5例晕厥(发生率为8.5/100万)[93]。2016-2017流行季在我国开展了一项针对3~17岁健康儿童青少年接种LAIV3的Ⅲ期RCT研究共纳入2 000名健康儿童青少年,其中998名接种LAIV疫苗,1 001名接种安慰剂,疫苗组和安慰剂组分别报告7起和4起不良事件,均被认为与接种疫苗无关,但疫苗组发热发生率比安慰剂组高,且在3~9岁年龄组更加明显(26.9% vs. 18.8%)[109]。

经鼻腔喷雾免疫后,LAIV毒株的排出是正常现象,但疫苗成分中的流感减毒病毒导致无免疫力的人感染极为罕见。英国在2016-2017和2017-2018流行季连续开展队列研究观察接种LAIV后病毒排出情况,研究显示,在连续两个流行季,A(H1N1)pdm09、A(H3N2)、B(Victoria)、B(Yamagata)四种疫苗株病毒排出检出率为8.2%、19.3%、31.0%、27.9%,并且受接种者年龄越小,排出疫苗株病毒的风险越大[169]。

(五) 疫苗成本效果、成本效益接种流感疫苗有效减少流感相关门急诊、住院和死亡人数,继而降低治疗费用,产生明显的经济效益。中国台州[68]、深圳[170]、中山[171]和常州[172]等地采用前瞻性队列、流行病学类试验和模型研究等发现,老年人、儿童和慢性基础性疾病患者接种流感疫苗均有较高的成本效益。此外,国外研究显示,ACS患者、孕妇接种流感疫苗也具有较高的成本效益[173-175]。美国一项模型研究显示,按照美国每年400万的孕产妇分娩量估计,接种IIV3可减少1 632例死产、120例孕产妇死亡、340例婴儿死亡、32 856例早产以及减少641例中度脑瘫,节省37亿美元,增加了81 696个质量调整生命年(QALY)[176]。

我国一项决策分析模型评估了6月龄~18岁儿童青少年接种IIV3、IIV4和LAIV的卫生经济学效果[177]。研究发现,在6月龄~3岁的儿童中,接种IIV3具有成本效果;在3~18岁的人群中,相比于IIV3和LAIV,接种IIV4最具成本效果。一项研究通过构建马尔科夫模型,对北京市在老年人中同时接种IIV3和23价肺炎球菌多糖疫苗(PPV23)的成本效果进行了分析,提示与不免费接种上述两种疫苗或仅实施免费接种IIV3相比,当前实施的为≥60岁老年人免费接种IIV3和≥65岁老年人免费接种PPV23的策略可节省成本和提高QALY[178]。

(六) 流感疫苗与其他疫苗或药物的同时使用1. 与非新冠病毒疫苗的使用:2019年9月至2020年6月在我国浙江、贵州和河南等地开展的一项Ⅳ期、多中心RCT研究评估6~11月龄人群IIV3与肠道病毒71型灭活疫苗(EV71)同时接种的免疫原性与安全性研究显示,EV71与IIV3同时接种组的3种流感病毒抗体阳转率、免后GMT均非劣效于IIV3单独接种组,同时接种组的EV71抗体阳转率、免后GMT均非劣效于EV71单独接种组,安全性方面3组间的不良事件发生率差异无统计学意义[179]。我国开展另一项评价3~7岁儿童IIV3与PPV23联合接种的研究显示,在免疫原性方面,IIV3与PPV23联合接种非劣效于两种疫苗单独接种;在安全性方面,一级不良反应在不同接种组之间差异无统计学意义,联合接种组的二级不良反应略高于单独接种组,各组间未发生三级及以上不良反应[180]。2021年11月至2022年5月在江苏省泰州市开展的一项评估≥60岁老年人同时接种IIV4和PPV23的安全性研究显示,无论是健康老年人还是合并慢性基础性疾病的老年人,同时接种IIV4和PPV23的安全性良好,同时接种28 d内,总体不良反应的发生率仅为2.07%(51/2 461),主要为Ⅰ级不良反应1.83%(45/2 461),未观察到Ⅳ级及以上不良反应及与疫苗相关的严重不良事件[181]。上海市浦东新区的一项评价≥60岁老年人同时接种IIV4和PPV23保护效果的研究发现,单独接种流感疫苗对老年人肺炎发生无交叉保护作用,单独接种肺炎疫苗对老年人肺炎的保护效果约为26%(95%CI:11%~45%),肺炎疫苗与流感疫苗联合接种对老年人肺炎的保护效果约为42%(95%CI:28%~50%),可减少老年人因肺炎的就诊及住院次数[182]。

既往研究提示,除了低年龄组婴儿出现热性惊厥的风险有可能增加外,IIV与儿童常规接种的免疫规划疫苗同时接种不影响疫苗免疫原性和安全性[9]。也有研究指出,6~23月龄儿童中IIV与13价肺炎球菌多糖结合疫苗(PCV13)联合接种会导致接种后0~1 d发热风险增加[183],IIV与PCV13、破伤风疫苗及百日咳疫苗联合使用会导致接种后0~1 d热性惊厥风险增加[166-167],但大多数此类发热反应发作短暂且预后良好[184]。儿童同时接种LAIV、麻腮风疫苗及水痘疫苗,与单独接种相比不会降低任何一种成分的免疫原性[185]。

国外研究提示,成年人同时接种PCV13[186-187]、破伤风疫苗或百日咳疫苗[188]、IIV,可观察到免疫原性降低,但无明确临床意义。≥50岁人群中的研究发现,IIV与带状疱疹减毒活疫苗同时接种和间隔4周接种相比,产生的抗体反应基本相同[189-190]。≥65岁人群中研究发现,同时接种IIV4和PPV23与间隔2周接种相比,同时接种组4~6周后对B系流感抗原的血清保护率较低,但在接种6个月后,4种流感抗原的血清保护率没有差异[191]。此外,IIV与带状疱疹减毒活疫苗[189-190]、PCV13[186-187]、PPV23[191-192]、破伤风类毒素[188]或百日咳疫苗[188]分别同时接种于成年人,具有可靠的安全性。

上述研究结果提示,绝大部分研究均未发现影响IIV和联合接种疫苗的免疫原性减弱和安全性降低的明确证据。虽然目前LAIV与其他疫苗联合接种研究相对有限,但均未发现安全性问题。WHO和美国CDC也在其流感疫苗预防接种技术指南中推荐IIV可以与其他IIV及LAIV同时或依次接种;如果同时接种2种LAIV,则需要至少间隔4周。

2. 与新冠病毒疫苗同时接种:2022年5月WHO更新的《流感疫苗立场文件(2022)》认为基于现有有限证据,IIV与现行使用的新冠病毒疫苗同时接种未观察到疫苗安全性和有效性受到影响,建议IIV可以与新冠病毒疫苗同时接种[9]。

英国在18~59岁人群中开展一项流感疫苗和新冠病毒疫苗同时接种的Ⅳ期RCT研究,研究对象在接种第2剂次新冠病毒疫苗(分别为腺病毒载体新冠病毒疫苗和mRNA新冠病毒疫苗)时同时接种流感疫苗(分别为三价佐剂疫苗、细胞培养的四价疫苗、重组四价疫苗),结果发现同时接种2种疫苗不良反应发生的概率未提示存在差异,且2种疫苗的抗体阳转率及抗体滴度亦未减弱[193]。美国开展了一项关于mRNA新冠病毒疫苗加强剂和流感疫苗同时接种反应原性的真实世界回顾性队列研究,发现与单独接种mRNA新冠病毒疫苗加强针相比,同时接种mRNA新冠病毒疫苗加强针和流感疫苗在疫苗接种后1周内报告全身不良反应的风险有所增加,但多为疲乏、头痛、肌肉酸痛等轻中度不良反应[194]。荷兰的一项研究调查了联合接种mRNA新冠疫苗加强针和IIV对疫苗安全性和抗体反应的影响,结果显示同时接种2种疫苗是安全的,但与单独接种加强针相比,新冠病毒的抗体滴度和中和作用有所降低,不能排除同时接种mRNA新冠疫苗和IIV会降低新冠疫苗保护性的可能;但实验各组之间血清中的流感抗体滴度没有差异,这表明可能的干扰并未延伸到针对流感的免疫反应中,同时该研究没有发现额外或更严重的不良事件[195]。意大利进行的研究显示,联合接种IIV和mRNA新冠疫苗加强针与单独接种mRNA新冠疫苗加强针相比,产生的新冠病毒抗体滴度下降较为明显[196]。

2021年3-5月,我国一项在18~59岁组人群开展的IIV4与新冠灭活疫苗同时接种的非劣效、Ⅳ期RCT研究,纳入480名研究对象进行分析,研究结果提示同时接种未增加不良事件发生风险,且流感疫苗的抗体阳性率和阳转率在同时接种组和间隔接种组间亦未存在显著差异[197]。同期开展的另一项IIV4和新冠灭活疫苗同时接种的多中心、非劣效、Ⅳ期RCT研究,进一步扩大了样本量(1 132名参与者)和人群范围(≥18岁),研究结果也支持IIV4和新冠灭活疫苗同时接种具有较好的安全性和免疫原性[198]。目前缺乏LAIV与国产新冠病毒疫苗同时接种的有效性和安全性的有关数据。

结合WHO立场文件及其关于新冠病毒疫苗和流感疫苗同时接种的建议,以及目前国际上发表的和我国已开展的有限的关于同时接种研究结果,经审慎考虑,认为≥18岁人群同时接种IIV和新冠病毒疫苗安全性和免疫原性是可以接受的,可以降低感染流感病毒或新冠病毒后出现严重疾病的风险,能够提高免疫接种效率,减少接种者前往接种门诊的次数。同时接种时应在两侧肢体接种部位分别进行接种。另一方面,还需要加强疫苗接种后不良事件监测,并开展更多的研究以积累更充分的同时接种证据。对于接种LAIV以及<18岁的未成年人,由于目前和新冠病毒疫苗同时接种的证据缺乏,建议与新冠病毒疫苗接种间隔 > 14 d。

3. 与药物的同时使用:免疫抑制剂(如皮质类激素、细胞毒性药物或放射治疗、器官移植)的使用可能影响接种后的免疫效果[199-201],为避免可能的药物间相互作用,任何正在进行的治疗均应咨询医生。服用流感抗病毒药物预防和治疗期间也可以接种IIV。由于LAIV含有活的流感病毒,抗流感病毒药物的使用可能会干扰LAIV的复制,从而影响其接种后的免疫反应,不建议两者同时使用。如果在接种LAIV前48 h至接种后14 d的间隔内使用抗病毒药物,可能会降低疫苗的有效性[202]。

四、2023-2024年度接种建议每年接种流感疫苗是预防流感最经济有效的措施。目前,流感疫苗在我国属于非免疫规划疫苗,公民知情、自愿接种。2022年4月国务院印发的《“十四五”国民健康规划》,要求强化疫苗预防接种,做好流感疫苗供应保障,推动重点人群流感疫苗接种。国务院应对新型冠状病毒感染疫情联防联控机制综合组2022年印发的《关于做好2022-2023年流行季流感防控工作的通知》(联防联控机制综发〔2022〕94号)要求高度重视流感防控工作,继续全面实施“强化监测预警、免疫重点人群、推进多病共防、规范疫情处置、落实医疗救治、广泛宣传动员”的综合举措,落实防控措施,依法科学做好流感防控工作。一是各地要积极采取措施,多渠道筹集资金,降低疫苗接种费用,及时做好流感疫苗接种工作准备。二是根据流感疫苗预防接种技术指南等文件,制订适宜的免疫策略和接种方案,要特别针对≥60岁老年人、医务人员、慢性病患者、6月龄~5岁儿童等重点和高风险人群优先开展接种,并鼓励有条件的地方对上述人群实施免费接种,提升流感疫苗接种率,降低流感聚集性疫情的发生。三是各地要统筹做好新冠病毒疫苗、流感疫苗和其他常规疫苗接种工作。根据流感疫苗接种需求、现有设施条件、现有预防接种服务能力和服务区域,通过组织集中接种、设立临时接种点或成年人接种门诊等形式,提供规范、便利的接种服务,提升流感疫苗接种服务能力和信息化管理水平。

2022年5月WHO发布的《流感疫苗立场文件(2022)》认为,接种流感疫苗主要目的是保护高危人群免受严重流感相关疾病和死亡的影响。从全球来看,现使用的季节性流感疫苗是安全有效的,能够显著预防发病和死亡,并建议所有国家应考虑实施季节性流感疫苗免疫规划[9]。

为指导公众科学认识和预防流感,提升防护意识和健康素养,逐步提高重点人群的疫苗覆盖率,各级CDC要积极组织开展科学普及、健康教育、风险沟通和疫苗政策推进活动,组织指导疫苗接种时,应重点把握好剂型选择、优先接种人群、接种程序、接种禁忌和接种时机等技术环节。

(一) 抗原组分WHO推荐的2023-2024年度北半球基于鸡胚生产的三价流感疫苗组分:A/Victoria/4897/2022(H1N1)pdm09类似株、A/Darwin/9/2021(H3N2)类似株和B/Austria/1359417/2021(Victoria系)类似株。四价流感疫苗组分:包含B型毒株的2个系,为上述3个毒株及B/Phuket/3073/2013(Yamagata系)类似株。与上一年度相比,本年度WHO推荐的疫苗组分中更换了A(H1N1)pdm09流感病毒亚型疫苗株。

(二) 疫苗种类及适用年龄组我国批准上市的流感疫苗包括三价灭活疫苗(IIV3)、三价减毒活疫苗(LAIV3)和四价灭活疫苗(IIV4),其中IIV3有裂解疫苗和亚单位疫苗,可用于≥6月龄人群接种,包括0.25 ml和0.5 ml两种剂型;LAIV3为冻干制剂,用于3~17岁人群,每剂次0.2 ml;IIV4为裂解疫苗和亚单位疫苗,可用于≥6月龄人群接种,包括0.25 ml和0.5 ml两种剂型。

对可接种不同类型、不同厂家疫苗产品的人群,可自愿接种任何一种流感疫苗,无优先推荐。具体流感疫苗生产企业、适用人群及其产品信息见表 1。

流感疫苗安全、有效。建议所有≥6月龄且无接种禁忌的人接种流感疫苗。结合流感疫情形势和多病共防的防控策略,尽可能降低流感的危害,优先推荐重点和高风险人群及时接种。

1. 医务人员:包括临床救治人员、公共卫生人员、卫生检疫人员等。医务人员接种流感疫苗既可预防个人因感染流感导致工作效率低下或缺勤影响医疗机构运转,又可有效避免传染流感给同事或患者,保障和维持医疗机构的正常接诊和救治能力。

2. ≥60岁老年人:患流感后死亡风险最高,是流感疫苗接种的重要目标人群。

3. 罹患一种或多种慢性病者:患有心血管疾病(单纯高血压除外)、慢性呼吸系统疾病、肝肾功能不全、血液病、神经系统疾病、神经肌肉功能障碍、代谢性疾病(包括糖尿病)等慢性病患者、患有免疫抑制疾病或免疫功能低下者,患流感后出现流感相关重症疾病的风险很高,应优先接种流感疫苗。

4. 养老机构、长期护理机构、福利院等人群聚集场所脆弱人群及员工:以上人员感染流感后发生严重临床结局的风险较高,接种流感疫苗可降低重症和死亡的风险,同时降低此类集体场所发生聚集性疫情的风险。

5. 孕妇:国内外大量研究证实孕妇罹患流感后发生重症、死亡和不良妊娠结局的风险更高,国外对孕妇在孕期任何阶段接种流感疫苗的安全性证据充分,且接种疫苗对预防孕妇罹患流感及通过胎传抗体保护<6月龄婴儿的效果明确[203]。但由于疫苗企业尚未获得国内妊娠期及哺乳期妇女的临床试验数据,既往我国上市的流感疫苗产品说明书将孕妇列为接种禁忌,随着更多证据的积累,部分产品的说明书中已明确孕妇接种流感疫苗“建议与医生共同进行获益/风险评估后决定”。为降低我国孕妇罹患流感及严重并发症风险,本指南建议孕妇可在妊娠任何阶段接种流感疫苗。

6. 6~59月龄的儿童:患流感后出现重症的风险高,流感住院负担重,应作为优先接种人群之一。

7. <6月龄婴儿的家庭成员和看护人员:由于现有流感疫苗不可以直接给<6月龄婴儿接种,该人群可通过母亲孕期接种和对婴儿的家庭成员和看护人员接种流感疫苗间接获益,以预防流感。

8. 重点场所人群:托幼机构、中小学校、监管场所等是容易发生流感等呼吸道传染病暴发疫情的重点场所,此类场所人群接种流感疫苗,可降低人群罹患流感风险和减少流感聚集性疫情的发生。

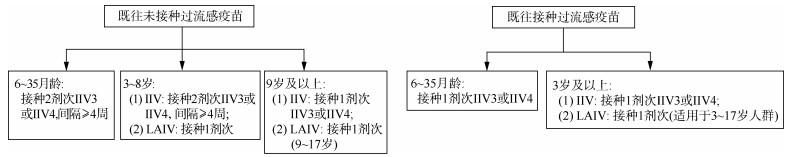

(四) 接种剂次1. 6月龄~8岁儿童:对IIV,首次接种流感疫苗的6月龄~8岁儿童应接种2剂次(2剂次选择同一剂型的疫苗),间隔≥4周;2022-2023年度或以前接种过1剂次或以上流感疫苗的儿童,则建议接种1剂次。对LAIV,无论是否接种过流感疫苗,仅接种1剂次。

2. ≥9岁儿童和成年人:仅需接种1剂次。见图 1。

|

| 图 1 各年龄组流感疫苗接种剂次图示 |

通常接种流感疫苗2~4周后,可产生具有保护水平的抗体。我国各地每年流感活动高峰出现的时间和持续时间不同,为保证受种者在流感高发季节前获得免疫保护,建议各地在疫苗可及后尽快安排接种工作,最好在当地流感流行季前完成免疫接种,接种单位在整个流行季节都可以提供免疫接种服务。同一流感流行季节,已按照接种程序完成全程接种的人员,无需重复接种。

孕妇在孕期的任一阶段均可接种流感疫苗,建议只要本年度的流感疫苗开始供应,可尽早接种。

(六) 接种部位及方法IIV的接种采用肌内注射。成年人和 > 1岁儿童首选上臂三角肌接种疫苗,6月龄~1岁婴幼儿的接种部位以大腿前外侧为最佳。LAIV的接种采用鼻内喷雾法,严禁注射。

(七) 疫苗储存IIV和LAIV的储存及运输都应保持在2~8 ℃条件下,严禁冻结。接种单位日常使用应按照《预防接种工作规范》和《疫苗储存和运输管理规范》的要求,做好温度监测。

(八) 接种禁忌对疫苗中所含任何成分(包括辅料、甲醛、裂解剂及抗生素)过敏者或有过任何一种流感疫苗接种严重过敏史者,禁止接种。

患有急性疾病、严重慢性疾病或慢性疾病的急性发作期以及发热患者,建议痊愈或者病情稳定控制后接种。既往接种流感疫苗后6周内出现格林-巴利综合征的患者,建议由医生评估后考虑是否接种。

禁止接种LAIV人群:①因使用药物、HIV感染等任何原因造成免疫功能低下者;②长期使用含有阿司匹林或水杨酸成分药物治疗的儿童及青少年;③2~4岁患有哮喘的儿童;④孕妇;⑤有格林-巴利综合征病史者;⑥接种前48 h使用过奥司他韦、扎那米韦等抗病毒药物者,或接种前5 d使用过帕拉米韦,或接种前17 d使用过巴洛沙韦者[202]。

《中华人民共和国药典》(2015版和2020版)均未将对鸡蛋过敏作为流感疫苗接种禁忌。药典规定流感全病毒灭活疫苗中卵清蛋白含量应≤250 ng/剂,裂解疫苗中卵清蛋白含量应≤200 ng/ml,暂无LAIV说明。我国常用的流感疫苗中的卵清蛋白含量测量显示含量最高不超过140 ng/ml[204]。国外学者对于鸡蛋过敏者接种IIV或LAIV的研究表明未见发生严重过敏反应[205-208]。美国免疫规划咨询委员会自2016年以来开始建议对鸡蛋过敏者亦可接种流感疫苗,且自2023-2024流感流行季起,无需采取额外的保障措施[202]。目前国内部分流感疫苗产品说明书中也未将鸡蛋过敏列为接种禁忌,因此本指南不将鸡蛋过敏作为流感疫苗接种禁忌。

(九) 与其他疫苗同时接种和药物对疫苗的影响1. 与非新冠病毒疫苗同时接种:综合考虑风险与收益,IIV与其他灭活疫苗及LAIV如EV71疫苗、肺炎球菌疫苗、带状疱疹疫苗、水痘疫苗、麻腮风疫苗、百白破疫苗可同时在不同部位接种。建议无PPV23接种史的≥60岁老年人,或前一剂PPV23接种间隔超过5年的≥65岁老年人,在当年流感季来临前联合接种流感疫苗和PPV23[209]。LAIV和其他疫苗同时接种的研究证据有限,LAIV与麻腮风疫苗或水痘疫苗同时接种不会干扰免疫反应[9]。在接种LAIV后,必须间隔4周以上才可接种其他LAIV[202]。

2. 与新冠病毒疫苗同时接种:综合多方证据,经审慎考虑,认为≥18岁人群可同时接种IIV和新冠病毒疫苗。同时接种时应在两侧肢体接种部位分别进行接种。另一方面,还需要加强疫苗接种后不良事件监测,并开展更多的研究以积累更充分的同时接种的证据。对于接种LAIV者以及<18岁的未成年人,由于目前和新冠病毒疫苗同时接种的证据缺乏,建议与新冠病毒疫苗接种间隔 > 14 d。

3. 药物对流感疫苗的影响:免疫抑制剂(如皮质类激素、细胞毒性药物或放射治疗、器官移植等)的使用可能影响接种后的免疫效果[200-201]。服用流感抗病毒药物预防和治疗期间也可以接种IIV[106]。预防或治疗性服用抗流感病毒药物会影响LAIV的免疫效果[202]。如正在或近期曾使用过任何其他疫苗或药物,包括非处方药,请接种前告知接种医生。为避免可能的药物间相互作用,任何正在进行的治疗均应咨询医生。

(十) 接种注意事项各接种单位要按照《预防接种工作规范》的要求开展流感疫苗接种工作。接种过程应遵循“三查七对一验证”的原则,同时要注意以下事项:

1. 疫苗瓶有裂纹、标签不清或失效者,疫苗出现浑浊等外观异物者均不得使用。

2. 严格掌握疫苗剂量和适用人群的年龄范围,不能将0.5 ml剂型分为2剂次(每剂次0.25 ml)使用。

3. 国外同类产品显示哮喘患者(任何年龄)、活动性喘息或反复喘息发作的儿童(<5岁)接种LAIV后喘息发作的风险增高,国内临床试验没有此类受试者的数据,建议慎用。

4. LAIV为鼻内喷雾接种,严禁注射。严重鼻塞会影响疫苗制剂在鼻腔内的扩散,减弱LAIV免疫效果,建议缓解后再行接种。

5. 植入人工耳蜗的儿童,在植入手术前一周及术后两周内应避免使用LAIV,防止因可能存在的脑脊液渗漏而造成严重后果。

6. 不同种类LAIV接种应至少间隔4周。

7. 接种完成后应告知接种对象现场留观至少30 min再离开。

8. 建议注射现场备1∶1 000肾上腺素等药品和其他抢救设施,以备偶有发生严重过敏反应时供急救使用。

9. 患有出血性疾病或者正在接受抗凝治疗的人群,肌内注射可能会出现注射部位出血、血肿等情况,需要明确告知受种者可能的风险,必要时咨询临床医生意见。

(十一) 接种记录及评估1. 实施接种后,医疗卫生人员应当在预防接种证/接种凭证以及预防接种信息系统登记疫苗接种的相关信息,包括疫苗的品种、上市许可持有人、最小包装单位的识别信息、有效期、接种时间、实施接种的医疗卫生人员、受种者等接种信息,确保接种信息可追溯、可查询。接种记录应当保存至疫苗有效期满后不少于五年备查。

2. 接种单位、乡(镇)卫生院、社区卫生服务中心、疾病预防控制机构,应按照规定的报告程序和报告内容,上报或收集、统计辖区接种实施情况。

3. 疾病预防控制机构按照《全国疑似预防接种异常反应监测方案》(2022版)的规定,开展监测和处置。

指南编写专家组:中国疾病预防控制中心传染病管理处彭质斌、郑亚明、郑建东、秦颖;中国疾病预防控制中心病毒病预防控制所王大燕、陈涛;中国医学科学院北京协和医学院群医学及公共卫生学院冯录召;北京市疾病预防控制中心传染病地方病控制所杨鹏;复旦大学公共卫生学院杨娟;河南省疾病预防控制中心免疫预防与规划所张延炀;上海市疾病预防控制中心综合保障处陈健;深圳市南山区疾病预防控制中心免疫规划科姜世强;青海省疾病预防控制中心慢性非传染性疾病预防控制所徐莉立;广东省疾病预防控制中心传染病预防控制所康敏

指南编写专家组秘书:中国疾病预防控制中心传染病管理处杨孝坤、赵宏婷

利益冲突 所有作者声明无利益冲突

| [1] |

WHO. Fact sheet on influenza(seasonal)[EB/OL]. (2023-01-12)[2023-07-30]. http://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/influenza-(seasonal).

|

| [2] |

王晴, 张慕丽, 秦颖, 等. 2011-2019年中国B型流感季节性、年龄特征和疫苗匹配度分析[J]. 中华流行病学杂志, 2020, 41(11): 1813-1817. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.cn112338-20200318-00375 Wang Q, Zhang ML, Qin Y, et al. Analysis on seasonality, age distribution of influenza B cases and matching degree of influenza B vaccine in China, 2011-2019[J]. Chin J Epidemiol, 2020, 41(11): 1813-1817. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.cn112338-20200318-00375 |

| [3] |

Dhanasekaran V, Sullivan S, Edwards KM, et al. Human seasonal influenza under COVID-19 and the potential consequences of influenza lineage elimination[J]. Nat Commun, 2022, 13(1): 1721. DOI:10.1038/s41467-022-29402-5 |

| [4] |

Cao L, Lu Y, Xie CJ, et al. Emerging triple-reassortant influenza C virus with household-associated infection during an influenza A (H3N2) outbreak, China, 2022[J]. Emerg Microbes Infect, 2023, 12(1): 2175593. DOI:10.1080/22221751.2023.2175593 |

| [5] |

Daniels RS, Galiano M, Ermetal B, et al. Temporal and Gene Reassortment Analysis of Influenza C Virus Outbreaks in Hong Kong, SAR, China[J]. J Virol, 2022, 96(3): e0192821. DOI:10.1128/jvi.01928-21 |

| [6] |

Vega-Rodriguez W, Ly H. Epidemiological, serological, and genetic evidence of influenza D virus infection in humans: Is it a justifiable cause for concern?[J]. Virulence, 2023, 14(1): 2150443. DOI:10.1080/21505594.2022.2150443 |

| [7] |

Yu JS, Li F, Wang D. The first decade of research advances in influenza D virus[J]. J Gen Virol, 2021, 102(1). DOI:10.1099/jgv.0.001529 |

| [8] |

中华人民共和国国家卫生健康委员会, 国家中医药管理局. 流行性感冒诊疗方案(2020年版)[J]. 中华临床感染病杂志, 2020, 13(6): 401-405. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1674-2397.2020.06.001 National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People's Republic of China. Protocol for diagnosis and treatment of influenza (2020 revised version)[J]. Chin J Clin Infect Dis, 2020, 13(6): 401-405. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1674-2397.2020.06.001 |

| [9] |

WHO. Vaccines against influenza: WHO position paper – May 2022[J]. Wkly Epidemiol Rec, 2022, 97(19): 185-208. |

| [10] |

Uyeki TM, Hui DS, Zambon M, et al. Influenza[J]. Lancet, 2022, 400(10353): 693-706. DOI:10.1016/s0140-6736(22)00982-5 |

| [11] |

Kim DK, Poudel B. Tools to detect influenza virus[J]. Yonsei Med J, 2013, 54(3): 560-566. DOI:10.3349/ymj.2013.54.3.560 |

| [12] |

Cowling BJ, Ip DK, Fang VJ, et al. Aerosol transmission is an important mode of influenza A virus spread[J]. Nat Commun, 2013, 4: 1935. DOI:10.1038/ncomms2922 |

| [13] |

Liao YR, Xue S, Xie YR, et al. Characterization of influenza seasonality in China, 2010-2018: Implications for seasonal influenza vaccination timing[J]. Influenza Other Respir Viruses, 2022, 16(6): 1161-1171. DOI:10.1111/irv.13047 |

| [14] |

Bryan Inho Kimpark O, Park O, Lee S. Comparison of influenza surveillance data from the Republic of Korea, selected northern hemisphere countries and Hong Kong Special Administrative Region SAR (China) from 2012 to 2017[J]. Western Pac Surveill Response J, 2020, 11(3): 1-9. DOI:10.5365/wpsar.2019.10.2.015 |

| [15] |

Newman LP, Bhat N, Fleming JA, et al. Global influenza seasonality to inform country-level vaccine programs: An analysis of WHO FluNet influenza surveillance data between 2011 and 2016[J]. PLoS One, 2018, 13(2): e0193263. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0193263 |

| [16] |

Igboh LS, Roguski K, Marcenac P, et al. Timing of seasonal influenza epidemics for 25 countries in Africa during 2010-19: a retrospective analysis[J]. The Lancet Global Health, 2023, 11(5): e729-739. DOI:10.1016/s2214-109x(23)00109-2 |

| [17] |

Yang J, Lau YC, Wu P, et al. Variation in Influenza B Virus Epidemiology by Lineage, China[J]. Emerg Infect Dis, 2018, 24(8): 1536-1540. DOI:10.3201/eid2408.180063 |

| [18] |

Huang WJ, Cheng YH, Tan MJ, et al. Epidemiological and virological surveillance of influenza viruses in China during 2020-2021[J]. Infect Dis Poverty, 2022, 11(1): 74. DOI:10.1186/s40249-022-01002-x |

| [19] |

国家流感中心. 中国流感监测周报[EB/OL]. (2023-07-09)[2023-07-10]. https://ivdc.chinacdc.cn/cnic/zyzx/lgzb/. Chinese National Influenza Center. Chinese Weekly Influenza Surveillance Report [EB/OL]. (2023-07-09)[2023-07-10]. https://ivdc.chinacdc.cn/cnic/zyzx/lgzb/. |

| [20] |

Swets MC, Russell CD, Harrison EM, et al. SARS-CoV-2 co-infection with influenza viruses, respiratory syncytial virus, or adenoviruses[J]. Lancet, 2022, 399(10334): 1463-1464. DOI:10.1016/s0140-6736(22)00383-x |

| [21] |

Iuliano AD, Roguski KM, Chang HH, et al. Estimates of global seasonal influenza-associated respiratory mortality: a modelling study[J]. Lancet, 2018, 391(10127): 1285-1300. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)33293-2 |

| [22] |

Somes MP, Turner RM, Dwyer LJ, et al. Estimating the annual attack rate of seasonal influenza among unvaccinated individuals: A systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Vaccine, 2018, 36(23): 3199-3207. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.04.063 |

| [23] |

龚慧, 申鑫, 严涵, 等. 2006-2019年中国季节性流感疾病负担估计[J]. 中华医学杂志, 2021, 101(8): 560-567. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.cn112137-20201210-03323 Gong H, Shen X, Yan H, et al. Estimating the disease burden of seasonal influenza in China, 2006-2019[J]. Natl Med J China, 2021, 101(8): 560-567. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.cn112137-20201210-03323 |

| [24] |

Li L, Liu Y, Wu P, et al. Influenza-associated excess respiratory mortality in China, 2010-15: a population-based study[J]. Lancet Public health, 2019, 4(9): e473-481. DOI:10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30163-X |

| [25] |

Lina B, Georges A, Burtseva E, et al. Complicated hospitalization due to influenza: results from the Global Hospital Influenza Network for the 2017-2018 season[J]. BMC Infect Dis, 2020, 20(1): 465. DOI:10.1186/s12879-020-05167-4 |

| [26] |

Mylonakis SC, Mylona EK, Kalligeros M, et al. How comorbidities affect hospitalization from influenza in the pediatric population[J]. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2022, 19(5): 2811. DOI:10.3390/ijerph19052811 |

| [27] |

Chen LL, Zhou SZ, Zhang ZW, et al. Cohort profile: China respiratory illness surveillance among pregnant women (CRISP), 2015-2018[J]. BMJ Open, 2018, 8(4): e019709. DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019709 |

| [28] |

Chen LL, Zhou SZ, Bao L, et al. Incidence rates of influenza illness during pregnancy in Suzhou, China, 2015-2018[J]. Influenza Other Respir Viruses, 2022, 16(1): 14-23. DOI:10.1111/irv.12888 |

| [29] |

Otieno NA, Nyawanda BO, Mcmorrow M, et al. The burden of influenza among Kenyan pregnant and postpartum women and their infants, 2015-2020[J]. Influenza Other Respir Viruses, 2022, 16(3): 452-461. DOI:10.1111/irv.12950 |

| [30] |

Racicot K, Kwon JY, Aldo P, et al. Understanding the complexity of the immune system during pregnancy[J]. Am J Reprod Immunol, 2014, 72(2): 107-116. DOI:10.1111/aji.12289 |

| [31] |

Soma-Pillay P, Nelson-Piercy C, Tolppanen H, et al. Physiological changes in pregnancy[J]. Cardiovasc J Afr, 2016, 27(2): 89-94. DOI:10.5830/CVJA-2016-021 |

| [32] |

Sappenfield E, Jamieson DJ, Kourtis AP. Pregnancy and susceptibility to infectious diseases[J]. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol, 2013, 2013, 752852. DOI:10.1155/2013/752852 |

| [33] |

Wang RT, Yan WX, Du M, et al. The effect of influenza virus infection on pregnancy outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies[J]. Int J Infect Dis, 2021, 105: 567-578. DOI:10.1016/j.ijid.2021.02.095 |

| [34] |

Mertz D, Lo CK, Lytvyn L, et al. Pregnancy as a risk factor for severe influenza infection: an individual participant data meta-analysis[J]. BMC Infect Dis, 2019, 19(1): 683. DOI:10.1186/s12879-019-4318-3 |

| [35] |

Wen T, Arditi B, Riley LE, et al. Influenza complicating delivery hospitalization and its association with severe maternal morbidity in the United States, 2000-2018[J]. Obstet Gynecol, 2021, 138(2): 218-227. DOI:10.1097/AOG.0000000000004462 |

| [36] |

Yu HJ, Feng ZJ, Uyeki TM, et al. Risk factors for severe illness with 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus infection in China[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2011, 52(4): 457-465. DOI:10.1093/cid/ciq144 |

| [37] |

Xu CL, Liu L, Ren BZ, et al. Incidence of influenza virus infections confirmed by serology in children and adult in a suburb community, northern China, 2018-2019 influenza season[J]. Influenza Other Respir Viruses, 2021, 15(2): 262-269. DOI:10.1111/irv.12805 |

| [38] |

Li J, Wang CF, Ruan LQ, et al. Development of influenza-associated disease burden pyramid in Shanghai, China, 2010-2017: a Bayesian modelling study[J]. BMJ Open, 2021, 11(9): e047526. DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-047526 |

| [39] |

Fraaij PL, Heikkinen T. Seasonal influenza: the burden of disease in children[J]. Vaccine, 2011, 29(43): 7524-7528. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.08.010 |

| [40] |

Wang X, Li Y, O'brien KL, et al. Global burden of respiratory infections associated with seasonal influenza in children under 5 years in 2018: a systematic review and modelling study[J]. Lancet Global Health, 2020, 8(4): e497-510. DOI:10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30545-5 |

| [41] |

Finnie TJ, Copley VR, Hall IM, et al. An analysis of influenza outbreaks in institutions and enclosed societies[J]. Epidemiol Infect, 2014, 142(1): 107-113. DOI:10.1017/S0950268813000733 |

| [42] |

Gaglani MJ. Editorial commentary: school-located influenza vaccination: why worth the effort?[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2014, 59(3): 333-335. DOI:10.1093/cid/ciu344 |

| [43] |

Fiore AE, Epperson S, Perrotta D, et al. Expanding the recommendations for annual influenza vaccination to school-age children in the United States[J]. Pediatrics, 2012, 129(Suppl 2): S54-62. DOI:10.1542/peds.2011-0737C |

| [44] |

Read JM, Zimmer S, Vukotich C, et al. Influenza and other respiratory viral infections associated with absence from school among schoolchildren in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA: a cohort study[J]. BMC Infect Dis, 2021, 21(1): 291. DOI:10.1186/s12879-021-05922-1 |

| [45] |

Zumofen MB, Frimpter J, Hansen SA. Impact of Influenza and Influenza-Like Illness on Work Productivity Outcomes: A Systematic Literature Review[J]. Pharmacoeconomics, 2023, 41(3): 253-273. DOI:10.1007/s40273-022-01224-9 |

| [46] |

Uscher-Pines L, Schwartz HL, Ahmed F, et al. Feasibility of social distancing practices in US schools to reduce influenza transmission during a pandemic[J]. Public Health Manag Pract, 2020, 26(4): 357-370. DOI:10.1097/phh.0000000000001174 |

| [47] |

曾晓旭, 谢怡然, 陈涛, 等. 中国2019-2020监测年度流感暴发疫情特征分析[J]. 国际病毒学杂志, 2021, 28(5): 359-363. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1673-4092.2021.05.002 Zeng XX, Xie YR, Chen T, et al. Analysis on epidemiological characteristics of influenza outbreaks in Chinese mainland from 2019 to 2020[J]. Int J Virol, 2021, 28(5): 359-363. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1673-4092.2021.05.002 |

| [48] |

Jenkin DC, Mahgoub H, Morales KF, et al. A rapid evidence appraisal of influenza vaccination in health workers: An important policy in an area of imperfect evidence[J]. Vaccine X, 2019, 2: 100036. DOI:10.1016/j.jvacx.2019.100036 |

| [49] |

Lietz J, Westermann C, Nienhaus A, et al. The Occupational Risk of Influenza A (H1N1) Infection among Healthcare Personnel during the 2009 Pandemic: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies[J]. PLoS One, 2016, 11(8): e0162061. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0162061 |

| [50] |

Pereira M, Williams S, Restrick L, et al. Healthcare worker influenza vaccination and sickness absence-an ecological study[J]. Clin Med (Lond), 2017, 17(6): 484-489. DOI:10.7861/clinmedicine.17-6-484 |

| [51] |

Mossad SB, Deshpande A, Schramm S, et al. Working Despite Having Influenza-Like Illness: Results of An Anonymous Survey of Healthcare Providers Who Care for Transplant Recipients[J]. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol, 2017, 38(8): 966-969. DOI:10.1017/ice.2017.91 |

| [52] |

Eibach D, Casalegno JS, Bouscambert M, et al. Routes of transmission during a nosocomial influenza A (H3N2) outbreak among geriatric patients and healthcare workers[J]. J Hosp Infect, 2014, 86(3): 188-193. DOI:10.1016/j.jhin.2013.11.009 |

| [53] |

Haviari S, Bénet T, Saadatian-Elahi M, et al. Vaccination of healthcare workers: A review[J]. Hum Vaccin Immunother, 2015, 11(11): 2522-2537. DOI:10.1080/21645515.2015.1082014 |

| [54] |

Tsagris V, Nika A, Kyriakou D, et al. Influenza A/H1N1/2009 outbreak in a neonatal intensive care unit[J]. J Hosp Infect, 2012, 81(1): 36-40. DOI:10.1016/j.jhin.2012.02.009 |

| [55] |

Zhang Y, Muscatello DJ, Wang Q, et al. Hospitalizations for influenza-associated severe acute respiratory infection, Beijing, China, 2014-2016[J]. Emerg Infect Dis, 2018, 24(11): 2098-2102. DOI:10.3201/eid2411.171410 |

| [56] |

Yu HJ, Huang JG, Huai Y, et al. The substantial hospitalization burden of influenza in central China: surveillance for severe, acute respiratory infection, and influenza viruses, 2010–2012[J]. Influenza Other Respir Viruses, 2014, 8(1): 53-65. DOI:10.1111/irv.12205 |

| [57] |

Langer J, Welch VL, Moran MM, et al. High Clinical Burden of Influenza Disease in Adults Aged ≥65 Years: Can We Do Better? A Systematic Literature Review[J]. Adv Ther, 2023, 40(4): 1601-1627. DOI:10.1007/s12325-023-02432-1 |

| [58] |

Wang H, Fu CX, Li KB, et al. Influenza associated mortality in Southern China, 2010-2012[J]. Vaccine, 2014, 32(8): 973-978. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.12.013 |

| [59] |

Yang L, Ma S, Chen PY, et al. Influenza associated mortality in the subtropics and tropics: results from three Asian cities[J]. Vaccine, 2011, 29(48): 8909-8914. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.09.071 |

| [60] |

Wu P, Goldstein E, Ho LM, et al. Excess mortality associated with influenza A and B virus in Hong Kong, 1998-2009[J]. J Infect Dis, 2012, 206(12): 1862-1871. DOI:10.1093/infdis/jis628 |

| [61] |

Chow A, Ma S, Ling AE, et al. Influenza-associated deaths in tropical Singapore[J]. Emerg Infect Dis, 2006, 12(1): 114-121. DOI:10.3201/eid1201.050826 |

| [62] |

Nunes B, Viboud C, Machado A, et al. Excess mortality associated with influenza epidemics in Portugal, 1980 to 2004[J]. PLoS One, 2011, 6(6): e20661. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0020661 |

| [63] |

Hansen CL, Chaves SS, Demont C, et al. Mortality Associated With Influenza and Respiratory Syncytial Virus in the US, 1999-2018[J]. JAMA Netw Open, 2022, 5(2): e220527. DOI:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.0527 |

| [64] |

Feng LZ, Shay DK, Jiang Y, et al. Influenza-associated mortality in temperate and subtropical Chinese cities, 2003-2008[J]. Bull World Health Organ, 2012, 90(4): 279-288B. DOI:10.2471/BLT.11.096958 |

| [65] |

Gallagher N, Johnston J, Crookshanks H, et al. Characteristics of respiratory outbreaks in care homes during four influenza seasons, 2011-2015[J]. J Hosp Infect, 2018, 99(2): 175-180. DOI:10.1016/j.jhin.2017.08.020 |

| [66] |

Yang J, Jit M, Leung KS, et al. The economic burden of influenza-associated outpatient visits and hospitalizations in China: a retrospective survey[J]. Infect Dis Poverty, 2015, 4: 44. DOI:10.1186/s40249-015-0077-6 |

| [67] |

Wang Y, Chen LL, Cheng FF, et al. Economic burden of influenza illness among children under 5 years in Suzhou, China: Report from the cost surveys during 2011/12 to 2016/17 influenza seasons[J]. Vaccine, 2021, 39(8): 1303-1309. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.12.075 |

| [68] |

刘令初, 靳妍, 何寒青, 等. 2018-2019年台州市老年人接种流感疫苗的成本效益[J]. 中国疫苗和免疫, 2020, 26(5): 552-555. Liu LC, Jin Y, He HQ, et al. Benefit-cost ratio of influenza vaccination among elderly people of Taizhou city during the 2018-2019 season[J]. Chin J of Vaccines and Immunization, 2020, 26(5): 552-555. |

| [69] |

涂正波, 万刚凤, 肖红茂. 2017-2018年南昌市城区流感病例经济负担和影响因素分析[J]. 现代预防医学, 2021, 48(1): 152-156. Tu ZB, Wang GF, Xiao HM. Economic burden and influencing factors of influenza cases in urban area of Nanchang City, 2017-2018[J]. Modern Preventive Medicine, 2021, 48(1): 152-156. |

| [70] |

Yang J, Jit M, Zheng YM, et al. The impact of influenza on the health related quality of life in China: an EQ-5D survey[J]. BMC Infect Dis, 2017, 17(1): 686. DOI:10.1186/s12879-017-2801-2 |

| [71] |

Yoshino Y, Wakabayashi Y, Kitazawa T. The clinical effect of seasonal flu vaccination on health-related quality of life[J]. Int J Gen Med, 2021, 14: 2095-2099. DOI:10.2147/IJGM.S309920 |

| [72] |

孟子延, 张家友, 张哲罡, 等. 四价流感病毒灭活疫苗在18~64岁人群免疫原性和安全性的系统综述和Meta分析[J]. 中华流行病学杂志, 2018, 39(12): 1636-1641. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2018.12.019 Meng ZY, Zhang JY, Zhang ZG, et al. Immunogenicity of inacitivated quadrivalent influenza vaccine in adults aged 18-64 years: A systematic review and Meta-analysis[J]. Chin J Epidemiol, 2018, 39(12): 1636-1641. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2018.12.019 |

| [73] |

Wang YX, Zhang YH, Wu HF, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a quadrivalent inactivated subunit non-adjuvanted influenza vaccine: A randomized, double-blind, active-controlled phase 1 clinical trial[J]. Vaccine, 2021, 39(29): 3871-3878. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.05.070 |

| [74] |

Zhang YH, Wang YX, Jia CY, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of an egg culture-based quadrivalent inactivated non-adjuvanted subunit influenza vaccine in subjects ≥3 years: A randomized, multicenter, double-blind, active-controlled phase Ⅲ, non-inferiority trial[J]. Vaccine, 2022, 40(34): 4933-4941. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.06.078 |

| [75] |

Minozzi S, Lytras T, Gianola S, et al. Comparative efficacy and safety of vaccines to prevent seasonal influenza: A systematic review and network meta-analysis[J]. EClinicalMedicine, 2022, 46: 101331. DOI:10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101331 |

| [76] |

Osterholm MT, Kelley NS, Sommer A, et al. Efficacy and effectiveness of influenza vaccines: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Lancet Infect Dis, 2012, 12(1): 36-44. DOI:10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70295-X |

| [77] |

Demicheli V, Jefferson T, Ferroni E, et al. Vaccines for preventing influenza in healthy adults[J]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2018, 2: CD001269. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD001269.pub6 |

| [78] |

Belongia EA, Simpson MD, King JP, et al. Variable influenza vaccine effectiveness by subtype: a systematic review and meta-analysis of test-negative design studies[J]. Lancet Infect Dis, 2016, 16(8): 942-951. DOI:10.1016/S1473-3099(16)00129-8 |

| [79] |

Su YX, Guo ZH, Gu X, et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness against influenza A during the delayed 2022/23 epidemic in Shihezi, China[J]. Vaccine, 2023. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2023.08.039 |

| [80] |

Zhou SZ, Greene CM, Song Y, et al. Review of the status and challenges associated with increasing influenza vaccination coverage among pregnant women in China[J]. Hum Vaccin Immunother, 2020, 16(3): 602-611. DOI:10.1080/21645515.2019.1664230 |

| [81] |

Munoz FM, Patel SM, Jackson LA, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of three seasonal inactivated influenza vaccines among pregnant women and antibody persistence in their infants[J]. Vaccine, 2020, 38(33): 5355-5363. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.05.059 |

| [82] |

Vesikari T, Virta M, Heinonen S, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of a quadrivalent inactivated influenza vaccine in pregnant women: a randomized, observer-blind trial[J]. Hum Vaccin Immunother, 2020, 16(3): 623-629. DOI:10.1080/21645515.2019.1667202 |

| [83] |

Nunes MC, Cutland CL, Dighero B, et al. Kinetics of hemagglutination-inhibiting antibodies following maternal influenza vaccination among mothers with and those without HIV infection and their infants[J]. J Infect Dis, 2015, 212(12): 1976-1987. DOI:10.1093/infdis/jiv339 |

| [84] |

Nakphook S, Patumanond J, Shrestha M, et al. Antibody responses induced by trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine among pregnant and non-pregnant women in Thailand: A matched cohort study[J]. PLoS One, 2021, 16(06): e0253028. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0253028 |

| [85] |

Steinhoff MC, Omer SB, Roy E, et al. Influenza immunization in pregnancy-antibody responses in mothers and infants[J]. N Engl J Med, 2010, 362(17): 1644-1646. DOI:10.1056/NEJMc0912599 |

| [86] |

Molgaard-Nielsen D, Fischer TK, Krause TG, et al. Effectiveness of maternal immunization with trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine in pregnant women and their infants[J]. J Intern Med, 2019, 286(4): 469-480. DOI:10.1111/joim.12947 |

| [87] |

Maltezou HC, Asimakopoulos G, Stavrou S, et al. Effectiveness of quadrivalent influenza vaccine in pregnant women and infants, 2018-2019[J]. Vaccine, 2020, 38(29): 4625-4631. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.04.060 |

| [88] |

Omer SB, Clark DR, Madhi SA, et al. Efficacy, duration of protection, birth outcomes, and infant growth associated with influenza vaccination in pregnancy: a pooled analysis of three randomised controlled trials[J]. Lancet Respir Med, 2020, 8(6): 597-608. DOI:10.1016/S2213-2600(19)30479-5 |

| [89] |

Nunes MC, Madhi SA. Influenza vaccination during pregnancy for prevention of influenza confirmed illness in the infants: A systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Hum Vaccin Immunother, 2018, 14(3): 758-766. DOI:10.1080/21645515.2017.1345385 |

| [90] |

Cuningham W, Geard N, Fielding JE, et al. Optimal timing of influenza vaccine during pregnancy: A systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Influenza Other Respir Viruses, 2019, 13(5): 438-452. DOI:10.1111/irv.12649 |

| [91] |

Zhong Z, Haltalli M, Holder B, et al. The impact of timing of maternal influenza immunization on infant antibody levels at birth[J]. Clin Exp Immunol, 2019, 195(2): 139-152. DOI:10.1111/cei.13234 |

| [92] |

Steinhoff MC, Macdonald N, Pfeifer D, et al. Influenza vaccine in pregnancy: policy and research strategies[J]. Lancet, 2014, 383(9929): 1611-1613. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60583-3 |

| [93] |

Esposito S, Nauta J, Lapini G, et al. Efficacy and safety of a quadrivalent influenza vaccine in children aged 6-35 months: A global, multiseasonal, controlled, randomized Phase Ⅲ study[J]. Vaccine, 2022, 40(18): 2626-2634. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.02.088 |

| [94] |

Shinjoh M, Furuichi M, Tsuzuki S, et al. Effectiveness of inactivated influenza and COVID-19 vaccines in hospitalized children in 2022/23 season in Japan-The first season of co-circulation of influenza and COVID-19[J]. Vaccine, 2023. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2023.06.082 |

| [95] |

骆淑英, 朱军礼, 吕梅斋, 等. 基于实验室检测结果病例-对照研究评价6-72月龄儿童流感疫苗效果[J]. 中华预防医学杂志, 2019, 53(6): 576-580. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-9624.2019.06.007 Luo SY, Zhu JL, Lyu MZ, et al. Evaluation of the influenza vaccine effectiveness among children aged 6 to 72 months based on the test-negative case control study design[J]. Chin J Prev Med, 2019, 53(6): 576-580. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-9624.2019.06.007 |

| [96] |

Chua H, Chiu SS, Chan ELY, et al. Effectiveness of partial and full influenza vaccination among children aged <9 years in Hong Kong, 2011-2019[J]. J Infect Dis, 2019, 220(10): 1568-1576. DOI:10.1093/infdis/jiz361 |

| [97] |

Fu CX, Greene CM, He Q, et al. Dose effect of influenza vaccine on protection against laboratory-confirmed influenza illness among children aged 6 months to 8 years of age in southern China, 2013/14-2015/16 seasons: a matched case-control study[J]. Hum Vaccin Immunother, 2020, 16(3): 595-601. DOI:10.1080/21645515.2019.1662267 |

| [98] |

姜明月, 冯录召. 对当前6~35月龄儿童全剂量流感疫苗使用的思考[J]. 中华预防医学杂志, 2023, 57(2): 281-285. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.cn112150-20220909-00890 Jiang MY, Feng LZ. Consideration on the usage of full-dose influenza vaccine for the infants aged 6-35 months old[J]. Chin J Prev Med, 2023, 57(2): 281-285. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.cn112150-20220909-00890 |

| [99] |

Robertson CA, Mercer M, Selmani A, et al. Safety and Immunogenicity of a Full-dose, Split-virion, Inactivated, Quadrivalent Influenza Vaccine in Healthy Children 6-35 Months of Age: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial[J]. Pediatr Infect Dis J, 2019, 38(3): 323-328. DOI:10.1097/inf.0000000000002227 |

| [100] |

Liu XQ, Park J, Xia SL, et al. Immunological non-inferiority and safety of a quadrivalent inactivated influenza vaccine versus two trivalent inactivated influenza vaccines in China: Results from two studies[J]. Hum Vaccin Immunother, 2022, 18(6): 2132798. DOI:10.1080/21645515.2022.2132798 |

| [101] |

CDC. Recommendations for Prevention and Control of Influenza in Children, 2023-2024[J]. Pediatrics, 2023. DOI:10.1542/peds.2023-063773 |

| [102] |

Zhang Y, Cao ZD, Costantino V, et al. Influenza illness averted by influenza vaccination among school year children in Beijing, 2013-2016[J]. Influenza Other Respir Viruses, 2018, 12(6): 687-694. DOI:10.1111/irv.12585 |

| [103] |

Zhang WQ, Gao JM, Chen LL, et al. Estimated influenza illnesses and hospitalizations averted by influenza vaccination among children aged 6-59 months in Suzhou, China, 2011/12 to 2015/16 influenza seasons[J]. Vaccine, 2020, 38(51): 8200-8205. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.10.069 |

| [104] |

Pepin S, Samson SI, Alvarez FP, et al. Impact of a quadrivalent inactivated influenza vaccine on influenza-associated complications and health care use in children aged 6 to 35 months: Analysis of data from a phase Ⅲ trial in the Northern and Southern Hemispheres[J]. Vaccine, 2019, 37(13): 1885-1888. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.01.059 |

| [105] |

Tsang TK, Fang VJ, Ip DKM, et al. Indirect protection from vaccinating children against influenza in households[J]. Nat Commun, 2019, 10(1): 106. DOI:10.1038/s41467-018-08036-6 |

| [106] |

Grohskopf LA, Alyanak E, Ferdinands JM, et al. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, United States, 2021-22 influenza season[J]. MMWR Recomm Rep, 2021, 70(5): 1-28. DOI:10.15585/mmwr.rr7005a1 |

| [107] |

Hoft DF, Babusis E, Worku S, et al. Live and inactivated influenza vaccines induce similar humoral responses, but only live vaccines induce diverse T-cell responses in young children[J]. J Infect Dis, 2011, 204(6): 845-853. DOI:10.1093/infdis/jir436 |

| [108] |

陶焱炀, 金鹏飞, 朱凤才. 流感减毒活疫苗预防儿童季节性流感保护效果的Meta分析[J]. 中华流行病学杂志, 2020, 41(1): 103-110. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2020.01.019 Tao YY, Jin PF, Zhu FC. Meta-analysis on effectiveness of live attenuated influenza vaccine against seasonal influenza in children[J]. Chin J Epidemiol, 2020, 41(1): 103-110. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2020.01.019 |

| [109] |

Wang SY, Zheng YH, Jin XY, et al. Efficacy and safety of a live attenuated influenza vaccine in Chinese healthy children aged 3-17 years in one study center of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 clinical trial, 2016/17 season[J]. Vaccine, 2020, 38(38): 5979-5986. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.07.019 |

| [110] |

Belshe RB, Mendelman PM, Treanor J, et al. The efficacy of live attenuated, cold-adapted, trivalent, intranasal influenzavirus vaccine in children[J]. N Engl J Med, 1998, 338(20): 1405-1412. DOI:10.1056/NEJM199805143382002 |

| [111] |

Block SL, Heikkinen T, Toback SL, et al. The efficacy of live attenuated influenza vaccine against influenza-associated acute otitis media in children[J]. Pediatr Infect Dis J, 2011, 30(3): 203-207. DOI:10.1097/INF.0b013e3181faac7c |

| [112] |

Boddington NL, Pearson I, Whitaker H, et al. Effectiveness of influenza vaccination in preventing hospitalization due to Influenza in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2021, 73(9): 1722-1732. DOI:10.1093/cid/ciab270 |

| [113] |

Pan Y, Wang QY, Yang P, et al. Influenza vaccination in preventing outbreaks in schools: A long-term ecological overview[J]. Vaccine, 2017, 35(51): 7133-7138. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.10.096 |

| [114] |

Sun Y, Yang P, Wang QY, et al. Influenza vaccination and non-pharmaceutical measure effectiveness for preventing influenza outbreaks in schools: A surveillance-based evaluation in Beijing[J]. Vaccines(Basel), 2020, 8(4): 714. DOI:10.3390/vaccines8040714 |

| [115] |

Lau YL, Wong WHS, Hattangdi-Haridas SR, et al. Evaluating impact of school outreach vaccination programme in Hong Kong influenza season 2018 - 2019[J]. Hum Vaccin Immunother, 2020, 16(4): 823-826. DOI:10.1080/21645515.2019.1678357 |

| [116] |

陈达芹, 蒋亚文, 黄芳, 等. 深圳市学龄儿童接种流感疫苗对缺课预防效果的实证研究[J]. 中华流行病学杂志, 2021, 42(10): 1900-1906. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.cn112338-20210723-00580 Chen DQ, Jiang YW, Huang F, et al. Effectiveness of influenza vaccination for school-age children in preventing school absenteeism in Shenzhen: an empirical study[J]. Chin J Epidemiol, 2021, 42(10): 1900-1906. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.cn112338-20210723-00580 |

| [117] |

Darvishian M, van den Heuvel ER, Bissielo A, et al. Effectiveness of seasonal influenza vaccination in community-dwelling elderly people: an individual participant data meta-analysis of test-negative design case-control studies[J]. Lancet Respir Med, 2017, 5(3): 200-211. DOI:10.1016/S2213-2600(17)30043-7 |

| [118] |

孙烨祥, 张弦, 沈鹏, 等. ≥70岁老年人接种流感疫苗的保护效果真实世界回顾性队列研究[J]. 中国疫苗和免疫, 2023, 29(3): 253-260. DOI:10.19914/j.CJVI.2023043 Sun YX, Zhang X, Shen P, et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness in elderly people ≥70 years of age in Yinzhou district of Ningbo city: a real-world retrospective cohort study[J]. Chin J of Vaccines and Immunization, 2023, 29(3): 253-260. DOI:10.19914/j.CJVI.2023043 |

| [119] |

Beyer WE, Mcelhaney J, Smith DJ, et al. Cochrane re-arranged: support for policies to vaccinate elderly people against influenza[J]. Vaccine, 2013, 31(50): 6030-6033. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.09.063 |

| [120] |

Chung H, Buchan SA, Campigotto A, et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness against all-cause mortality following laboratory-confirmed influenza in older adults, 2010-2011 to 2015-2016 seasons in Ontario, Canada[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2021, 73(5): e1191-1199. DOI:10.1093/cid/ciaa1862 |

| [121] |

Chard AN, Nogareda F, Regan AK, et al. End-of-season influenza vaccine effectiveness during the Southern Hemisphere 2022 influenza season - Chile, Paraguay, and Uruguay[J]. Int J Infect Dis, 2023, 134: 39-44. DOI:10.1016/j.ijid.2023.05.015 |

| [122] |

Xiao TL, Wei MM, Guo XK, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of quadrivalent influenza vaccine among young and older adults in Tianjin, China: implication of immunosenescence as a risk factor[J]. Immun Ageing, 2023, 20(1): 37. DOI:10.1186/s12979-023-00364-6 |

| [123] |

Olafsdottir TA, Alexandersson KF, Sveinbjornsson G, et al. Age and Influenza-Specific Pre-Vaccination Antibodies Strongly Affect Influenza Vaccine Responses in the Icelandic Population whereas Disease and Medication Have Small Effects[J]. Front Immunol, 2017, 8: 1872. DOI:10.3389/fimmu.2017.01872 |

| [124] |

CDC. Licensure of a high-dose inactivated influenza vaccine for persons aged ≥65 years (Fluzone High-Dose)and guidance for use - United States, 2010[J]. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 2010, 59(16): 485-486. |

| [125] |

Sanchez L, Nakama T, Nagai H, et al. Superior immunogenicity of high-dose quadrivalent inactivated influenza vaccine versus Standard-Dose vaccine in Japanese Adults ≥ 60 years of age: Results from a phase Ⅲ, randomized clinical trial[J]. Vaccine, 2023, 41(15): 2553-2561. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2023.02.071 |

| [126] |

Chen JY, Hsieh SM, Hwang SJ, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of high-dose quadrivalent influenza vaccine in older adults in Taiwan: A phase Ⅲ, randomized, multi-center study[J]. Vaccine, 2022, 40(45): 6450-6454. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.09.078 |

| [127] |

Wilkinson K, Wei Y, Szwajcer A, et al. Efficacy and safety of high-dose influenza vaccine in elderly adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Vaccine, 2017, 35(21): 2775-2780. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.03.092 |

| [128] |

Diazgranados CA, Dunning AJ, Kimmel M, et al. Efficacy of high-dose versus standard-dose influenza vaccine in older adults[J]. N Engl J Med, 2014, 371(7): 635-645. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa1315727 |

| [129] |

Izurieta HS, Thadani N, Shay DK, et al. Comparative effectiveness of high-dose versus standard-dose influenza vaccines in US residents aged 65 years and older from 2012 to 2013 using Medicare data: a retrospective cohort analysis[J]. Lancet Infect Dis, 2015, 15(3): 293-300. DOI:10.1016/S1473-3099(14)71087-4 |

| [130] |

Shay DK, Chillarige Y, Kelman J, et al. Comparative effectiveness of high-dose versus standard-dose influenza vaccines among US medicare beneficiaries in preventing postinfluenza deaths during 2012-2013 and 2013-2014[J]. J Infect Dis, 2017, 215(4): 510-517. DOI:10.1093/infdis/jiw641 |

| [131] |

Young-Xu Y, van Aalst R, Mahmud SM, et al. Relative vaccine effectiveness of high-dose versus standard-dose influenza vaccines among veterans health administration patients[J]. J Infect Dis, 2018, 217(11): 1718-1727. DOI:10.1093/infdis/jiy088 |

| [132] |

Doyle JD, Beacham L, Martin ET, et al. Relative and absolute effectiveness of high-dose and standard-dose influenza vaccine against influenza-related hospitalization among older adults-United States, 2015-2017[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2021, 72(6): 995-1003. DOI:10.1093/cid/ciaa160 |

| [133] |

Izurieta HS, Chillarige Y, Kelman J, et al. Relative effectiveness of influenza vaccines among the United States elderly, 2018-2019[J]. J Infect Dis, 2020, 222(2): 278-287. DOI:10.1093/infdis/jiaa080 |

| [134] |

Mcconeghy KW, Davidson HE, Canaday DH, et al. Cluster-randomized Trial of Adjuvanted Versus Nonadjuvanted Trivalent Influenza Vaccine in 823 US Nursing Homes[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2021, 73(11): e4237-4243. DOI:10.1093/cid/ciaa1233 |

| [135] |

Dunkle LM, Izikson R, Patriarca P, et al. Efficacy of Recombinant Influenza Vaccine in Adults 50 Years of Age or Older[J]. N Engl J Med, 2017, 376(25): 2427-2436. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa1608862 |

| [136] |

Schwarze J, Openshaw P, Jha A, et al. Influenza burden, prevention, and treatment in asthma-A scoping review by the EAACI Influenza in asthma task force[J]. Allergy, 2018, 73(6): 1151-1181. DOI:10.1111/all.13333 |

| [137] |

Vasileiou E, Sheikh A, Butler C, et al. Effectiveness of influenza vaccines in asthma: A systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2017, 65(8): 1388-1395. DOI:10.1093/cid/cix524 |

| [138] |

黄远东, 赵晓平, 万涛, 等. 慢性阻塞性肺病人群流感疫苗接种的效果观察[J]. 海南医学, 2011, 22(4): 29-31. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1003-6350.2011.04.011 Huang YD, Zhao XP, Wan T, et al. Effects of influenza vaccination in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease[J]. Hai-nan Med J, 2011, 22(4): 29-31. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1003-6350.2011.04.011 |

| [139] |

高忠翠, 李江涛, 展胜. 卡舒宁联合流感疫苗对老年性慢性支气管炎合并急性感染的防治效果[J]. 中国生物制品学杂志, 2011, 24(10): 1214-1216. DOI:10.13200/j.cjb.2011.10.99.gaozhc.030 Gao ZC, Li JT, Zhan S. Preventive and curative effects of Card Shu Ning Combined with Influenza Vaccine on senile chronic bronchitis complicated with acute infection[J]. Chin J Biol, 2011, 24(10): 1214-1216. DOI:10.13200/j.cjb.2011.10.99.gaozhc.030 |

| [140] |

Clar C, Oseni Z, Flowers N, et al. Influenza vaccines for preventing cardiovascular disease[J]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2015(5): CD005050. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD005050.pub3 |

| [141] |

Behrouzi B, Bhatt DL, Cannon CP, et al. Association of influenza vaccination with cardiovascular risk: A meta-analysis[J]. JAMA Netw Open, 2022, 5(04): e228873. DOI:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.8873 |

| [142] |

Modin D, Jørgensen ME, Gislason G, et al. Influenza vaccine in heart failure[J]. Circulation, 2019, 139(5): 575-586. DOI:10.1161/circulationaha.118.036788 |

| [143] |

Goeijenbier M, van Sloten TT, Slobbe L, et al. Benefits of flu vaccination for persons with diabetes mellitus: A review[J]. Vaccine, 2017, 35(38): 5095-5101. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.07.095 |

| [144] |

Collins JP, Campbell AP, Openo K, et al. Clinical features and outcomes of immunocompromised children hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed influenza in the United States, 2011-2015[J]. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc, 2019, 8(6): 539-549. DOI:10.1093/jpids/piy101 |

| [145] |

Imai C, Toizumi M, Hall L, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the direct epidemiological and economic effects of seasonal influenza vaccination on healthcare workers[J]. PLoS One, 2018, 13(6): e0198685. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0198685 |

| [146] |

Al Qahtani AA, Selim M, Hamouda NH, et al. Seasonal influenza vaccine effectiveness among health-care workers in Prince Sultan Military Medical City, Riyadh, KSA, 2018-2019[J]. Hum Vaccin Immunother, 2021, 17(1): 119-123. DOI:10.1080/21645515.2020.1764827 |

| [147] |

黄勋, 冯录召, 杜小幸, 等. 中国医疗机构工作人员流感疫苗预防接种指南[J]. 中国感染控制杂志, 2023, 22(8): 871-885. DOI:10.12138/j.issn.1671-9638.20233814 Huang X, Feng LZ, Du XX, et al. Guideline on influenza vaccination for staff in Chinese medical institutions[J]. Chin J Infect Control, 2023, 22(8): 871-885. DOI:10.12138/j.issn.1671-9638.20233814 |

| [148] |

Mordant FL, Price OH, Rudraraju R, et al. Antibody titres elicited by the 2018 seasonal inactivated influenza vaccine decline by 3 months post-vaccination but persist for at least 6 months[J]. Influenza Other Respir Viruses, 2023, 17(1): e13072. DOI:10.1111/irv.13072 |

| [149] |

Liao YT, Jin Y, Zhang HJ, et al. Immunogenicity of a trivalent influenza vaccine and persistence of induced immunity in adults aged ≥60 years in Taizhou City, Zhejiang Province, China, during the 2018-2019 season[J]. Hum Vaccin Immunother, 2022, 18(5): 2071061. DOI:10.1080/21645515.2022.2071061 |

| [150] |

Young B, Zhao XH, Cook AR, et al. Do antibody responses to the influenza vaccine persist year-round in the elderly? A systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Vaccine, 2017, 35(2): 212-221. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.11.013 |

| [151] |

Shu LM, Zhang J, Huo X, et al. Surveillance on the Immune Effectiveness of Quadrivalent andTrivalent Split Influenza Vaccines - Shenzhen Cityand Changzhou City, China, 2018-2019[J]. China CDC Wkly, 2020, 2(21): 370-375. DOI:10.46234/ccdcw2020.095 |

| [152] |

Davis CW, Jackson KJL, Mccausland MM, et al. Influenza vaccine-induced human bone marrow plasma cells decline within a year after vaccination[J]. Science, 2020, 370(6513): 237-241. DOI:10.1126/science.aaz8432 |

| [153] |

Feng S, Chiu SS, Chan ELY, et al. Effectiveness of influenza vaccination on influenza-associated hospitalisations over time among children in Hong Kong: a test-negative case-control study[J]. Lancet Respir Med, 2018, 6(12): 925-934. DOI:10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30419-3 |

| [154] |

Ye BW, Shu LM, Pang YY, et al. Repeated influenza vaccination induces similar immune protection as first-time vaccination but with differing immune responses[J]. Influenza Other Respir Viruses, 2023, 17(1): e13060. DOI:10.1111/irv.13060 |

| [155] |

Martínez-Baz I, Navascués A, Casado I, et al. Simple models to include influenza vaccination history when evaluating the effect of influenza vaccination[J]. Euro Surveill, 2021, 26(32): 2001099. DOI:10.2807/1560-7917.Es.2021.26.32.2001099 |

| [156] |

Demicheli V, Jefferson T, Di Pietrantonj C, et al. Vaccines for preventing influenza in the elderly[J]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2018, 2: CD004876. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD004876.pub4 |

| [157] |

Jefferson T, Rivetti A, Di Pietrantonj C, et al. Vaccines for preventing influenza in healthy children[J]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2018, 2(2): Cd004879. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD004879.pub5 |

| [158] |

Berry BB, Ehlert DA, Battiola RJ, et al. Influenza vaccination is safe and immunogenic when administered to hospitalized patients[J]. Vaccine, 2001, 19(25/26): 3493-3498. DOI:10.1016/s0264-410x(01)00068-8 |

| [159] |

Bansal A, Trieu MC, Mohn KGI, et al. Safety, immunogenicity, efficacy and effectiveness of inactivated influenza vaccines in healthy pregnant women and children under 5 years: An evidence-based clinical review[J]. Front Immunol, 2021, 12: 744774. DOI:10.3389/fimmu.2021.744774 |

| [160] |

杨晓明, 高福, 俞永新, 等. 当代新疫苗(第二版)[M]. 北京: 高等教育出版社, 2020. Yang XM, Gao F, Yu YX, et al. A New Generation of Vaccine (Second Edition)[M]. Beijing: Higher Education Press, 2020. |

| [161] |

Basu I, Agarwal M, Shah V, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of two quadrivalent influenza vaccines in healthy adult and elderly participants in India-A phase Ⅲ, active-controlled, randomized clinical study[J]. Hum Vaccin Immunother, 2022, 18(1): 1-10. DOI:10.1080/21645515.2021.1885278 |

| [162] |

Vesikari T, Nauta J, Lapini G, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of quadrivalent versus trivalent inactivated subunit influenza vaccine in children and adolescents: A phase Ⅲ randomized study[J]. Int J Infect Dis, 2020, 92: 29-37. DOI:10.1016/j.ijid.2019.12.010 |

| [163] |

van de Witte S, Nauta J, Montomoli E, et al. A Phase Ⅲ randomised trial of the immunogenicity and safety of quadrivalent versus trivalent inactivated subunit influenza vaccine in adult and elderly subjects, assessing both anti-haemagglutinin and virus neutralisation antibody responses[J]. Vaccine, 2018, 36(40): 6030-6038. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.04.043 |

| [164] |

任敏睿, 李克莉, 李媛, 等. 中国2018-2019年和2019-2020年流感季流感疫苗疑似预防接种异常反应监测[J]. 中国疫苗和免疫, 2023(2): 197-203. DOI:10.19914/j.CJVI.2023034 Ren MR, Li KL, Li Y, et al. Surveillance for adverse events following immunization with influenza vaccine in China during the2018-2019 and 2019-2020 influenza seasons[J]. Chin J of Vaccines and Immunization, 2023(2): 197-203. DOI:10.19914/j.CJVI.2023034 |

| [165] |

Leung AK, Hon KL, Leung TN. Febrile seizures: an overview[J]. Drugs Context, 2018, 7: 212536. DOI:10.7573/dic.212536 |

| [166] |

Duffy J, Weintraub E, Hambidge SJ, et al. Febrile seizure risk after vaccination in children 6 to 23 months[J]. Pediatrics, 2016, 138(1): e20160320. DOI:10.1542/peds.2016-0320 |

| [167] |

Li R, Stewart B, Mcneil MM, et al. Post licensure surveillance of influenza vaccines in the Vaccine Safety Datalink in the 2013-2014 and 2014-2015 seasons[J]. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf, 2016, 25(8): 928-934. DOI:10.1002/pds.3996 |

| [168] |

Perego G, Vigezzi GP, Cocciolo G, et al. Safety and efficacy of spray intranasal live attenuated influenza vaccine: Systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Vaccines (Basel), 2021, 9(9): 998. DOI:10.3390/vaccines9090998 |

| [169] |

Jackson D, Pitcher M, Hudson C, et al. Viral shedding in recipients of live attenuated influenza vaccine in the 2016-2017 and 2017-2018 influenza seasons in the United Kingdom[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2020, 70(12): 2505-2513. DOI:10.1093/cid/ciz719 |

| [170] |

杜芳, 王蒲生, 黄琇棠, 等. 深圳市65岁以上老年人群接种流感疫苗的成本-效果分析[J]. 中国卫生经济, 2021, 40(10): 74-78. Du F, Wang PS, Huang XT, et al. Cost-effectiveness Analysis of Seasonal Influenza Vaccine in the Elderly over 65 Years Old in Shenzhen[J]. Chin Health Economics, 2021, 40(10): 74-78. |

| [171] |

陈秀云, 彭楚灵, 陈秋莲, 等. 中山市托幼儿童季节性流感疫苗接种效果及效益分析[J]. 公共卫生与预防医学, 2016, 27(4): 87-89. Chen XY, Peng CL, Chen QL, et al. Analysis on the effect and benefit of seasonal influenza vaccination in children in Zhongshan City[J]. J Pub Health Prev Med, 2016, 27(4): 87-89. |

| [172] |

许敏锐, 强德仁, 潘英姿, 等. 慢性病患者接种流感疫苗的效果与效益评价[J]. 公共卫生与预防医学, 2020, 31(5): 21-24. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1006-2483.2020.05.006 Xu MR, Qiang DR, Pan YZ, et al. Effect and cost-benefit of influenza vaccination for patients with chronic diseases[J]. J Pub Health Prev Med, 2020, 31(5): 21-24. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1006-2483.2020.05.006 |

| [173] |

Myers ER, Misurski DA, Swamy GK. Influence of timing of seasonal influenza vaccination on effectiveness and cost-effectiveness in pregnancy[J]. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 2011, 204(6 Suppl 1): S128-140. DOI:10.1016/j.ajog.2011.04.009 |

| [174] |

Hoshi SL, Shono A, Seposo X, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of influenza vaccination during pregnancy in Japan[J]. Vaccine, 2020, 38(46): 7363-7371. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.09.024 |

| [175] |

Xu J, Zhou FJ, Reed C, et al. Cost-effectiveness of seasonal inactivated influenza vaccination among pregnant women[J]. Vaccine, 2016, 34(27): 3149-3155. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.04.057 |

| [176] |

Chaiken SR, Hersh AR, Zimmermann MS, et al. Cost-effectiveness of influenza vaccination during pregnancy[J]. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med, 2022, 35(25): 5244-5252. DOI:10.1080/14767058.2021.1876654 |

| [177] |

Gong YL, Yao XL, Peng J, et al. Cost-Effectiveness and Health Impacts of Different Influenza Vaccination Strategies for Children in China[J]. Am J Prev Med, 2023, 65(1): 155-164. DOI:10.1016/j.amepre.2023.01.028 |

| [178] |

Pi Z, Aoyagi K, Arima K, et al. Optimization of Elderly Influenza and Pneumococcal Immunization Programs in Beijing, China Using Health Economic Evaluations: A Modeling Study[J]. Vaccines (Basel), 2023, 11(1): 161. DOI:10.3390/vaccines11010161 |

| [179] |

Chen YP, Xiao YH, Ye Y, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of an inactivated enterovirus 71 vaccine coadministered with trivalent split-virion inactivated influenza vaccine: A phase 4, multicenter, randomized, controlled trial in China[J]. Front Immunol, 2022, 13: 1080408. DOI:10.3389/fimmu.2022.1080408 |

| [180] |

汪志国, 孙翔, 张岷, 等. 3~7岁儿童同时接种23价肺炎球菌多糖疫苗和流感病毒裂解疫苗的免疫原性及安全性研究[J]. 中华微生物学和免疫学杂志, 2019, 39(10): 758-762. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-5101.2019.10.006 Wang ZG, Sun X, Zhang M, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of co-immunization with 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine and influenza virus split vaccine for children aged 3-7 years[J]. Chin J Microbiol Immunol, 2019, 39(10): 758-762. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-5101.2019.10.006 |

| [181] |

朱中奎, 卢希, 唐万琴, 等. 四价流感病毒裂解疫苗和23价肺炎球菌多糖疫苗在≥60岁老年人中同时接种的安全性评价[J]. 中华预防医学杂志, 2023, 57(9): 114-119. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.cn112150-20230417-00295 Zhu ZK, Lu X, Tang WQ, et al. Safety evaluation of simultaneous administration of quadrivalent influenza split virion vaccine and 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine in adults aged 60 years and older[J]. Chin J Prev Med, 2023, 57(9): 114-119. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.cn112150-20230417-00295 |

| [182] |

杨来宝, 扶雪莲, 肖绍坦, 等. 上海市浦东新区60岁以上老年人接种流感疫苗与23价肺炎球菌多糖疫苗效果评估[J]. 中国生物制品学杂志, 2022, 35(12): 1471-1476. DOI:10.13200/j.cnki.cjb.003779 Yang LB, Fu XL, Xiao ST, et al. Efficacy evaluation of influenza vaccine and 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine in elderly over 60 years old in Pudong New Area, Shanghai[J]. Chin J Biologicals, 2022, 35(12): 1471-1476. DOI:10.13200/j.cnki.cjb.003779 |

| [183] |

Stockwell MS, Broder K, Larussa P, et al. Risk of fever after pediatric trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine and 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine[J]. JAMA Pediatr, 2014, 168(3): 211-219. DOI:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.4469 |

| [184] |

Patterson JL, Carapetian SA, Hageman JR, et al. Febrile seizures[J]. Pediatric Ann, 2013, 42(12): 249-254. DOI:10.3928/00904481-20131122-09 |

| [185] |

Nolan T, Bernstein DI, Block SL, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of concurrent administration of live attenuated influenza vaccine with measles-mumps-rubella and varicella vaccines to infants 12 to 15 months of age[J]. Pediatrics, 2008, 121(3): 508-516. DOI:10.1542/peds.2007-1064 |

| [186] |

Frenck RW, Gurtman A, Rubino J, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of a 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine administered concomitantly with an influenza vaccine in healthy adults[J]. Clin Vaccine Immunol, 2012, 19(8): 1296-1303. DOI:10.1128/CVI.00176-12 |

| [187] |

Schwarz TF, Flamaing J, Rumke HC, et al. A randomized, double-blind trial to evaluate immunogenicity and safety of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine given concomitantly with trivalent influenza vaccine in adults aged ≥65 years[J]. Vaccine, 2011, 29(32): 5195-5202. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.05.031 |

| [188] |

Mcneil SA, Noya F, Dionne M, et al. Comparison of the safety and immunogenicity of concomitant and sequential administration of an adult formulation tetanus and diphtheria toxoids adsorbed combined with acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine and trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine in adults[J]. Vaccine, 2007, 25(17): 3464-3474. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.12.047 |

| [189] |

Kerzner B, Murray AV, Cheng E, et al. Safety and immunogenicity profile of the concomitant administration of ZOSTAVAX and inactivated influenza vaccine in adults aged 50 and older[J]. J Am Geriatr Soc, 2007, 55(10): 1499-1507. DOI:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01397.x |

| [190] |

Levin MJ, Buchwald UK, Gardner J, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of zoster vaccine live administered with quadrivalent influenza virus vaccine[J]. Vaccine, 2018, 36(1): 179-185. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.08.029 |

| [191] |

Nakashima K, Aoshima M, Ohfuji S, et al. Immunogenicity of simultaneous versus sequential administration of a 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine and a quadrivalent influenza vaccine in older individuals: A randomized, open-label, non-inferiority trial[J]. Hum Vaccin Immunother, 2018, 14(8): 1923-1930. DOI:10.1080/21645515.2018.1455476 |

| [192] |

Song JY, Cheong HJ, Tsai TF, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of concomitant MF59-adjuvanted influenza vaccine and 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine administration in older adults[J]. Vaccine, 2015, 33(36): 4647-4652. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.05.003 |

| [193] |

Lazarus R, Baos S, Cappel-Porter H, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of concomitant administration of COVID-19 vaccines (ChAdOx1 or BNT162b2) with seasonal influenza vaccines in adults in the UK (ComFluCOV): a multicentre, randomised, controlled, phase 4 trial[J]. Lancet, 2021, 398(10318): 2277-2287. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02329-1 |

| [194] |

Hause AM, Zhang B, Yue X, et al. Reactogenicity of simultaneous COVID-19 mRNA booster and influenza vaccination in the US[J]. JAMA Netw Open, 2022, 5(7): e2222241. DOI:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.22241 |

| [195] |

Dulfer EA, Geckin B, Taks EJM, et al. Timing and sequence of vaccination against COVID-19 and influenza (TACTIC): a single-blind, placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial[J]. Lancet Reg Health Eur, 2023, 29: 100628. DOI:10.1016/j.lanepe.2023.100628 |

| [196] |

Stefanizzi P, Tafuri S, Bianchi FP. Immunogenicity of third dose of anti-SARS-CoV-2 vaccine co-administered with influenza vaccine: An open question[J]. Hum Vaccin Immunother, 2022, 18(6): 2094653. DOI:10.1080/21645515.2022.2094653 |

| [197] |

Wang SY, Duan XQ, Bo C, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of a SARS-CoV-2 inactivated vaccine (CoronaVac)co-administered with an inactivated quadrivalent influenza vaccine: A randomized, open-label, controlled study in healthy adults aged 18 to 59 years in China[J]. Vaccine, 2022, 40(36): 5356-5365. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.07.021 |

| [198] |

Chen H, Huang Z, Chang S, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of an inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine (Sinopharm BBIBP-CorV) coadministered with quadrivalent split-virion inactivated influenza vaccine and 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine in China: A multicentre, non-inferiority, open-label, randomised, controlled, phase 4 trial[J]. Vaccine, 2022, 40(36): 5322-5332. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.07.033 |

| [199] |

Launay O, Abitbol V, Krivine A, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of influenza vaccine in inflammatory bowel disease patients treated or not with immunomodulators and/or biologics: A two-year prospective study[J]. J Crohns Colitis, 2015, 9(12): 1096-1107. DOI:10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjv152 |

| [200] |

Huemer HP. Possible immunosuppressive effects of drug exposure and environmental and nutritional effects on infection and vaccination[J]. Mediators Inflamm, 2015, 2015, 349176. DOI:10.1155/2015/349176 |

| [201] |