文章信息

- 宋明钰, 赵禹碹, 韩雨廷, 吕筠, 余灿清, 裴培, 杜怀东, 陈君石, 陈铮鸣, 孙点剑一, 李立明, 代表中国慢性病前瞻性研究项目协作组.

- Song Mingyu, Zhao Yuxuan, Han Yuting, Lyu Jun, Yu Canqing, Pei Pei, Du Huaidong, Chen Junshi, Chen Zhengming, Sun Dianjianyi, Li Liming, for the China Kadoorie Biobank Collaborative Group

- 中国10个地区成年人外周血嵌合染色体变异的流行病学分布特征

- Epidemiological distribution characteristics of peripheral blood mosaic chromosomal alteration in adults from 10 regions of China

- 中华流行病学杂志, 2023, 44(7): 1021-1026

- Chinese Journal of Epidemiology, 2023, 44(7): 1021-1026

- http://dx.doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn112338-20230306-00129

-

文章历史

收稿日期: 2023-03-06

2. 北京大学公众健康与重大疫情防控战略研究中心, 北京 100191;

3. 英国牛津大学医学研究委员会人口健康研究组, 牛津 OX3 7LF;

4. 英国牛津大学临床与流行病学研究中心纳菲尔德人群健康系, 牛津 OX3 7LF;

5. 国家食品安全风险评估中心, 北京 100022

2. Peking University Center for Public Health and Epidemic Preparedness & Response, Beijing 100191, China;

3. Medical Research Council Population Health Research Unit, University of Oxford, Oxford OX3 7LF, United Kingdom;

4. Clinical Trial Service Unit and Epidemiological Studies Unit, Nuffield Department of Population Health, University of Oxford, Oxford OX3 7LF, United Kingdom;

5. China National Center for Food Safety Risk Assessment, Beijing 100022, China

嵌合染色体变异(mosaic chromosomal alteration,mCA)是指受精卵形成后,染色体水平上超过1 Mb基因改变的体细胞突变现象[1-2]。相较于单核苷酸突变以及短插入/缺失突变,mCA对基因组稳定性、完整性以及细胞功能的影响更大,是人类衰老的表型之一[3-4]。既往研究提示,外周血mCA增高全死因死亡风险[5-6],与血液恶性肿瘤[7-9]、多种实体瘤(如肺癌[10-11]、泌尿生殖系统肿瘤[11-12]等)、感染性疾病(如肺炎、消化系统感染)[11, 13]等的发生风险存在正向关联。既往研究报告mCA在人群中的检出率在1%~30%之间[7-8, 10-12, 14-17],识别我国人群中mCA的流行病学分布特征,一方面有助于识别分子水平上的衰老人群以及以肿瘤为主的多种慢性病的高危人群,实现个体水平上年龄相关性疾病的早发现,开展精准预防;另一方面可为后续进一步探索mCA的成因及其影响因素提供线索,有助于从分子抗衰层面开展年龄相关疾病一级预防的新探索、新实践,为推动我国人群健康老龄化提供高质量本土化基础研究证据。本研究以中国慢性病前瞻性研究(China Kadoorie Biobank,CKB)10个项目地区中已有基线数据、外周血基因分型数据的人群为基础,描述mCA在我国10个地区30~79岁自然人群的流行病学分布特征。

对象与方法1. 研究对象: CKB项目于2004-2008年开展基线调查,共纳入51.3万名30~79岁的研究对象,研究对象的纳入排除标准参见文献[18]。研究现场包括中国5个城市地区(山东省青岛市、黑龙江省哈尔滨市、海南省海口市、江苏省苏州市、广西壮族自治区柳州市)和5个农村地区(四川省彭州市、甘肃省天水市、河南省辉县市、浙江省桐乡市、湖南省浏阳市)。基线调查内容包括问卷调查、体格检查和血标本采集。项目于2015-2016年对100 640名研究对象的血液标本进行全基因组基因分型,由华大基因科技服务有限公司使用针对中国汉族人定制的基因芯片(Affymetrix Axiom® CKB Array)完成。本研究剔除基因分型质量不佳的个体(342名)和基线体质指数(BMI)缺失者(1名),最终保留100 297名研究对象进行统计分析。

2. 研究内容: mCA表型通过嵌合染色体变异工作流(Mosaic Chromosomal Alterations,MoChA)计算[5, 19]。该工作流利用基因芯片原始的基因强度数据,计算log R比值和B等位基因频率两个核心指标[20],对基因型数据进行长距离单倍体分型[21],分别估算总等位基因强度以及相对等位基因强度。MoChA可同时识别常染色体和性染色体上的mCA,将识别到的mCA分为4类[7-8]:①获赠突变;②缺失突变;③拷贝数中性的杂合性缺失突变(copy-neutral loss of heterozygosity,CN-LOH);④其他未明确亚型的mCA。对于性染色体mCA,MoChA目前仅能对缺失作出准确判别,因此本研究的性染色体mCA指嵌合Y染色体缺失(mosaic loss of Y chromosome,mLOY)和嵌合X染色体缺失(mosaic loss of X chromosome,mLOX)。mCA携带者定义为携带常染色体mCA、mLOY或mLOX中任意一种突变的研究对象。

研究对象基线的一般社会人口学信息(年龄、性别、职业、文化程度、家庭年收入)、生活方式(吸烟状况、饮酒状况、膳食摄入情况、体力活动水平、睡眠质量)、过去一年抑郁症状和过去两年经历的负性生活事件情况由统一培训的调查员通过面对面问卷调查获得。南北方的划分以秦岭-淮河为界。健康膳食指的是每日摄入新鲜蔬菜、每日摄入新鲜水果,同时限制红肉摄入(< 7 d/周)。体力活动水平根据一天工作和休闲活动的运动代谢当量值(代谢当量-h/d)的中位数分为高、低两组[22]。睡眠质量根据平均睡眠时长(含午休)和失眠症状评价。抑郁症状指过去一年曾出现情绪低落、兴趣缺乏、丧失食欲和负罪感、自责的情况,并且持续2周以上。负性生活事件包括10项:夫妻离异/分居、配偶死亡、严重的家庭内部矛盾或冲突、家庭其他成员死亡或患重病、丧失经济来源/负债度日、失业/下岗/退休、自营企业或家庭经济破产、遭受暴力/被强暴、严重创伤或车祸、严重自然灾害。研究对象根据自身情况回答“是/否”。身高、体重和腰围由调查员根据标准操作手册采用统一工具测量获得。BMI=体重(kg)/身高(m)2。依据《中国成人超重和肥胖症预防控制指南》对个体体重进行分类[23]:①BMI < 18.5 kg/m2为低体重;②18.5~23.9 kg/m2为正常体重;③24.0~27.9 kg/m2为超重;④≥28.0 kg/m2为肥胖。根据腰围(cm)判定中心性肥胖:男性≥90,女性≥85。

3. 统计学分析: 本研究的检出率为mCA携带者在研究人群中的构成比,mLOY和mLOX的检出率仅在对应性别的研究对象中进行计算。报告检出率时,参照2010年全国人口普查的年龄性别构成(5岁为一组)进行直接标准化。本研究:①描述mCA事件及其亚型在染色体层面的分布;②分性别描述mCA检出率的地区和年龄分布特征;③描述mCA检出率的人群分布特征。采用二分类logistic回归模型,报告调整年龄、性别和地区的检出率和P值。描述年龄、性别和地区分布时,不调整对应分组变量。采用乘法交互模型,评价年龄、性别对mCA检出率是否存在交互作用。本研究采用R 4.2.1软件进行数据分析,双侧检验,检验水准α=0.05。

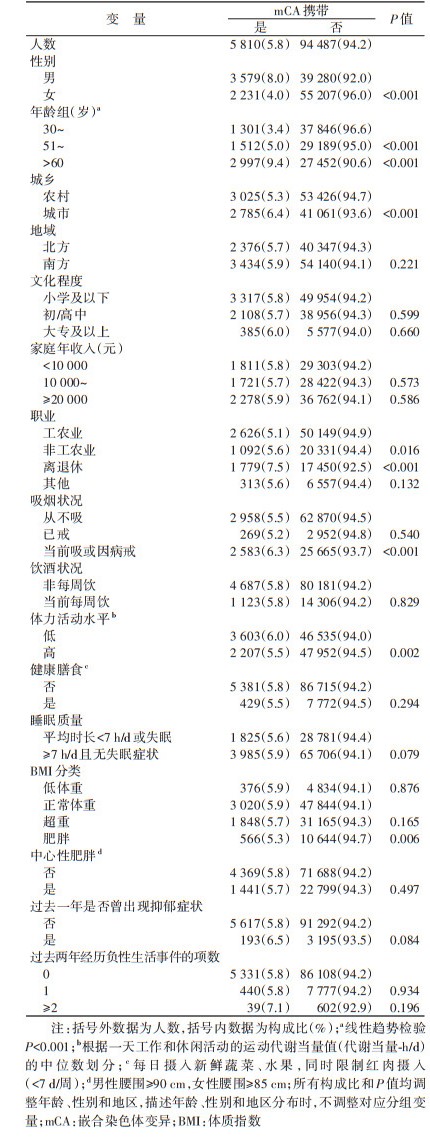

结果1. 基本情况: 共纳入100 297名研究对象,年龄(53.7±11.0)岁,男性占42.7%,城市地区人群占43.7%。研究人群中共检出5 810名mCA携带者,检出率为5.8%,见表 1。携带者中,5 489名(94.5%)仅检出1种mCA,321名(5.5%)检出≥2种mCA,mCA最高可达16种。根据2010年全国人口结构标准化后的研究人群mCA检出率为5.1%。

2. 染色体分布: 本研究检出mCA事件数为6 195例,其中常染色体mCA事件数2 888例(2 625名研究对象),mLOY 2 458例(2 458名研究对象),mLOX 849例(849名研究对象)(图 1A),检出率分别为2.6%、5.7%和1.5%。常染色体上不同亚型mCA的分布见图 1B。其中,1号(248例)、14号(204例)和19号(194例)染色体的突变数最高,18号(60例)和21号(49例)染色体突变数最低。常染色体mCA中,超半数为CN-LOH(62.0%),缺失和获赠突变分别占17.5%和7.7%。除20号染色体以缺失突变为主、21号染色体以获赠突变为主外,其余常染色体以CN-LOH为主要突变类型。

|

| 图 1 研究人群中嵌合染色体变异(mCA)事件及其亚型的染色体分布 |

3. 地区分布: 城市mCA检出率(6.4%)高于农村(5.3%),差异有统计学意义(P < 0.001),南北方地区mCA检出率差异无统计学意义(表 1)。10个项目地区中,海口(13.0%)、柳州(11.8%)和青岛(11.7%)项目地区的男性mCA检出率较高;河南(4.7%)、苏州(4.5%)和青岛(4.4%)项目地区的女性mCA检出率较高(图 2A)。

|

| 注:A:调整年龄;B:调整10个项目地区,交互检验P < 0.001 图 2 不同性别研究人群嵌合染色体变异(mCA)检出率的地区、年龄分布 |

4. 人群分布: mCA检出率存在明显的年龄和性别差异(表 1,图 2B)。mCA检出率随着基线年龄的增加逐渐升高,30~、51~、> 60岁人群mCA检出率分别为3.4%、5.0%和9.4%(趋势检验P < 0.001)。男性检出率(8.0%)高于女性(4.0%),差异有统计学意义(P < 0.001)。各年龄组男性mCA的检出率均高于女性,且二者之间的差异随着年龄的升高而加大(交互检验P < 0.001),≥65岁男、女性mCA检出率的差异达到最大(15.9% vs. 5.9%)。不同特征人群的mCA携带状态的分布见表 1。与目前职业工农业者相比(5.1%),非工农业者(5.6%)和离退休人员(7.5%)的mCA检出率更高,差异均有统计学意义(P < 0.05)。不同文化程度、不同家庭收入的人群间mCA检出率差异无统计学意义。行为方式特征方面,当前吸烟或因病戒烟者mCA检出率(6.3%)和低体力活动水平者mCA检出率(6.0%)分别较从不吸烟(5.5%)、高体力活动水平(5.5%)者更高,组间差异均有统计学意义(P < 0.05)。肥胖人群mCA检出率(5.3%)低于正常体重人群(5.9%),差异有统计学意义(P=0.006)。不同饮酒状况、膳食状况、睡眠状况、是否中心性肥胖的人群间,mCA检出率差异无统计学意义。过去一年抑郁症状以及过去两年间经历负性生活事件数不同的人群间mCA检出率差异无统计学意义。

讨论本研究利用CKB项目10万余名研究对象基线调查数据和基因数据,描述了我国10地区30~79岁成年人外周血mCA携带者的流行病学分布特征。本研究发现mCA检出率存在地区和人群分布差异。表现为mCA检出率随年龄的增长逐渐增加,在男性、离退休人员、非工农业劳动者、当前吸烟或因病戒烟者、低体力活动水平者检出率较高。

本研究得到的mCA在染色体层面的分布与既往研究结论一致[8, 14, 19, 24]。首先,mLOY是最常见的mCA类型。英国生物银行(United Kingdom Biobank,UKB)一项研究纳入206 353名男性,发现其mLOY的检出率为19.3%[25],而自然人群中常染色体mCA的检出率多在1%~5%[7-8, 26-27]。相较于常染色体和X染色体,Y染色体在体细胞存活与有丝分裂过程中起到的作用较小,即机体对mLOY具有更高的耐受性[28]。另外,常染色体mCA中,CN-LOH为主要突变类型。这一现象可能与CN-LOH通常覆盖更多基因[8],与其他亚型相比更易检出有关[3]。

本研究人群中mCA检出率低于既往其他基于MoChA工作流的大规模人群研究(n > 10 000)的mCA检出率。如开展于UKB的研究(n=444 199,平均年龄57岁,男性46.1%)发现无血液癌症的个体中mCA检出率为14.9%[11]。该差异可能是因为UKB人群平均年龄和男性占比均高于CKB人群。既往研究已明确年龄、性别是mCA的影响因素[2-3]。本研究同时观察到mCA随年龄的增长趋势在不同性别间存在差异,男性检出率随年龄增长迅速增加,而女性则表现为线性的缓慢增长。因此,mCA检出率的性别差异随年龄增加逐渐加大,既往研究也曾观察到类似现象[11]。mCA携带者的性别分布差异可能与男、女性先天遗传差异[29]以及后天暴露的环境因素差异有关,其背后的生物学机制有待进一步探索。

开展于人群结构与CKB类似的芬兰基因研究工程(FinnGen)人群(n=175 690,平均年龄53岁,男性40.4%)发现的mCA检出率(12.5%)[11]仍明显高于本研究。结果提示mCA检出率可能还存在种族差异。既往研究曾发现白种人中的检出率高于黄种人和黑人[15]。

除年龄、性别外,本研究发现mCA在不同行为特征的人群间存在差异,总的来说,采取相对健康生活方式的人群(从不吸烟、较高体力活动水平)mCA的检出率更低。吸烟具有公认的致突变作用[30],本研究发现的不同吸烟状态人群间mCA检出率的差异与既往研究结果近似[11]。同时,本研究发现高体力活动水平人群mCA检出率较低,其可能机制为运动可提高体细胞抗氧化能力,增强DNA自我修复,降低体细胞突变率[31]。BMI方面,虽然通常认为BMI在正常范围内是相对健康的,但本研究发现肥胖者mCA检出率低于体重正常人群,既往研究曾观察到类似结果[6],这可能是由于吸烟的混杂效应。与当前吸烟人群相比,从不吸烟的人群更易肥胖[32]。目前相关研究较少,该结论仍需后续研究进一步验证。

本研究存在局限性。首先,CKB项目地区、研究人群的选择并未采用概率抽样方法[33],因此本研究结果在外推到全国总体情况时需要谨慎。其次,本研究结果仅代表研究对象基线时的mCA状况,不能观察到mCA随时间的变化情况。

本研究描述了mCA在我国自然人群中的地区和人群分布,为进一步探索mCA的影响因素、识别分子衰老高危人群提供线索。未来研究可继续开展对研究对象mCA水平的长期纵向监测以及对其疾病表型关联谱的探索,分析mCA与表观遗传学、环境暴露因素等的关联,为推动年龄相关性疾病早期诊断与防控、减轻疾病负担提供科学依据。

利益冲突 所有作者声明无利益冲突

作者贡献声明 宋明钰:分析数据、结果解释、撰写论文;赵禹碹:分析与复核数据;韩雨廷:结果解释、论文修改;吕筠、余灿清、裴培、杜怀东:实施研究、采集数据;陈君石、陈铮鸣、李立明:项目设计、方案制定、经费支持;孙点剑一:构思研究、结果解释、论文修改、经费支持

志谢 感谢所有参加中国慢性病前瞻性研究项目的队列成员和各项目地区的现场调查队调查员;感谢项目管理委员会、国家项目办公室、牛津协作中心和10个项目地区办公室的工作人员

| [1] |

Biesecker LG, Spinner NB. A genomic view of mosaicism and human disease[J]. Nat Rev Genet, 2013, 14(5): 307-320. DOI:10.1038/nrg3424 |

| [2] |

Liu XX, Kamatani Y, Terao C. Genetics of autosomal mosaic chromosomal alteration (mCA)[J]. J Hum Genet, 2021, 66(9): 879-885. DOI:10.1038/s10038-021-00964-4 |

| [3] |

Dai XQ, Guo XH. Decoding and rejuvenating human ageing genomes: lessons from mosaic chromosomal alterations[J]. Ageing Res Rev, 2021, 68: 101342. DOI:10.1016/j.arr.2021.101342 |

| [4] |

Forsberg LA, Rasi C, Razzaghian HR, et al. Age-related somatic structural changes in the nuclear genome of human blood cells[J]. Am J Hum Genet, 2012, 90(2): 217-228. DOI:10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.12.009 |

| [5] |

Loh PR, Genovese G, Handsaker RE, et al. Insights into clonal haematopoiesis from 8, 342 mosaic chromosomal alterations[J]. Nature, 2018, 559(7714): 350-355. DOI:10.1038/s41586-018-0321-x |

| [6] |

Loftfield E, Zhou WY, Graubard BI, et al. Predictors of mosaic chromosome Y loss and associations with mortality in the UK Biobank[J]. Sci Rep, 2018, 8(1): 12316. DOI:10.1038/s41598-018-30759-1 |

| [7] |

Jacobs KB, Yeager M, Zhou WY, et al. Detectable clonal mosaicism and its relationship to aging and cancer[J]. Nat Genet, 2012, 44(6): 651-658. DOI:10.1038/ng.2270 |

| [8] |

Laurie CC, Laurie CA, Rice K, et al. Detectable clonal mosaicism from birth to old age and its relationship to cancer[J]. Nat Genet, 2012, 44(6): 642-650. DOI:10.1038/ng.2271 |

| [9] |

Lin SH, Brown DW, Rose B, et al. Incident disease associations with mosaic chromosomal alterations on autosomes, X and Y chromosomes: insights from a phenome-wide association study in the UK Biobank[J]. Cell Biosci, 2021, 11(1): 143. DOI:10.1186/s13578-021-00651-z |

| [10] |

Qin N, Wang C, Chen CC, et al. Association of the interaction between mosaic chromosomal alterations and polygenic risk score with the risk of lung cancer: an array-based case-control association and prospective cohort study[J]. Lancet Oncol, 2022, 23(11): 1465-1474. DOI:10.1016/S1470-2045(22)00600-3 |

| [11] |

Zekavat SM, Lin SH, Bick AG, et al. Hematopoietic mosaic chromosomal alterations increase the risk for diverse types of infection[J]. Nat Med, 2021, 27(6): 1012-1024. DOI:10.1038/s41591-021-01371-0 |

| [12] |

Zhou WY, Machiela MJ, Freedman ND, et al. Mosaic loss of chromosome Y is associated with common variation near TCL1A[J]. Nat Genet, 2016, 48(5): 563-568. DOI:10.1038/ng.3545 |

| [13] |

Hubbard AK, Brown DW, Machiela MJ. Clonal hematopoiesis due to mosaic chromosomal alterations: impact on disease risk and mortality[J]. Leuk Res, 2023, 126: 107022. DOI:10.1016/j.leukres.2023.107022 |

| [14] |

Terao C, Suzuki A, Momozawa Y, et al. Chromosomal alterations among age-related haematopoietic clones in Japan[J]. Nature, 2020, 584(7819): 130-135. DOI:10.1038/s41586-020-2426-2 |

| [15] |

Gao T, Ptashkin R, Bolton KL, et al. Interplay between chromosomal alterations and gene mutations shapes the evolutionary trajectory of clonal hematopoiesis[J]. Nat Commun, 2021, 12(1): 338. DOI:10.1038/s41467-020-20565-7 |

| [16] |

Thompson DJ, Genovese G, Halvardson J, et al. Genetic predisposition to mosaic Y chromosome loss in blood[J]. Nature, 2019, 575(7784): 652-657. DOI:10.1038/s41586-019-1765-3 |

| [17] |

Machiela MJ, Zhou WY, Karlins E, et al. Female chromosome X mosaicism is age-related and preferentially affects the inactivated X chromosome[J]. Nat Commun, 2016, 7: 11843. DOI:10.1038/ncomms11843 |

| [18] |

李立明, 吕筠, 郭彧, 等. 中国慢性病前瞻性研究: 研究方法和调查对象的基线特征[J]. 中华流行病学杂志, 2012, 33(3): 249-255. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2012.03.001 Li LM, Lv J, Guo Y, et al. The China Kadoorie Biobank: related methodology and baseline characteristics of the participants[J]. Chin J Epidemiol, 2012, 33(3): 249-255. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2012.03.001 |

| [19] |

Loh PR, Genovese G, McCarroll SA. Monogenic and polygenic inheritance become instruments for clonal selection[J]. Nature, 2020, 584(7819): 136-141. DOI:10.1038/s41586-020-2430-6 |

| [20] |

Peiffer DA, Le JM, Steemers FJ, et al. High-resolution genomic profiling of chromosomal aberrations using Infinium whole-genome genotyping[J]. Genome Res, 2006, 16(9): 1136-1148. DOI:10.1101/gr.5402306 |

| [21] |

Loh PR, Danecek P, Palamara PF, et al. Reference-based phasing using the Haplotype Reference Consortium panel[J]. Nat Genet, 2016, 48(11): 1443-1448. DOI:10.1038/ng.3679 |

| [22] |

Chen ZM, Chen JS, Collins R, et al. China Kadoorie Biobank of 0.5 million people: survey methods, baseline characteristics and long-term follow-up[J]. Int J Epidemiol, 2011, 40(6): 1652-1666. DOI:10.1093/ije/dyr120 |

| [23] |

中华人民共和国卫生部疾病控制司. 中国成人超重和肥胖症预防控制指南[M]. 北京: 人民卫生出版社, 2006. Division of Disease Control, Ministry of Health. The guideline for prevention and control of overweight and obesity in Chinese adults[M]. Beijing: People's Medical Publishing House, 2006. |

| [24] |

Fukami M, Miyado M. Mosaic loss of the Y chromosome and men's health[J]. Reprod Med Biol, 2022, 21(1): e12445. DOI:10.1002/rmb2.12445 |

| [25] |

Lin SH, Loftfield E, Sampson JN, et al. Mosaic chromosome Y loss is associated with alterations in blood cell counts in UK Biobank men[J]. Sci Rep, 2020, 10(1): 3655. DOI:10.1038/s41598-020-59963-8 |

| [26] |

Vattathil S, Scheet P. Extensive hidden genomic mosaicism revealed in normal tissue[J]. Am J Hum Genet, 2016, 98(3): 571-578. DOI:10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.02.003 |

| [27] |

Schick UM, McDavid A, Crane PK, et al. Confirmation of the reported association of clonal chromosomal mosaicism with an increased risk of incident hematologic cancer[J]. PLoS One, 2013, 8(3): e59823. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0059823 |

| [28] |

Guo XH, Dai XQ, Zhou T, et al. Mosaic loss of human Y chromosome: what, how and why[J]. Hum Genet, 2020, 139(4): 421-446. DOI:10.1007/s00439-020-02114-w |

| [29] |

Dunford A, Weinstock DM, Savova V, et al. Tumor-suppressor genes that escape from X-inactivation contribute to cancer sex bias[J]. Nat Genet, 2017, 49(1): 10-16. DOI:10.1038/ng.3726 |

| [30] |

Sato S, Seino Y, Ohka T, et al. Mutagenicity of smoke condensates from cigarettes, cigars and pipe tobacco[J]. Cancer Lett, 1977, 3: 1-8. DOI:10.1016/s0304-3835(77)93662-x |

| [31] |

Cash SW, Beresford SAA, Vaughan TL, et al. Recent physical activity in relation to DNA damage and repair using the comet assay[J]. J Phys Act Health, 2014, 11(4): 770-776. DOI:10.1123/jpah.2012-0278 |

| [32] |

Dare S, Mackay DF, Pell JP. Relationship between smoking and obesity: a cross-sectional study of 499, 504 middle- aged adults in the UK general population[J]. PLoS One, 2015, 10(4): e0123579. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0123579 |

| [33] |

Chen ZM, Lee L, Chen JS, et al. Cohort profile: the kadoorie study of chronic disease in China (KSCDC)[J]. Int J Epidemiol, 2005, 34(6): 1243-1249. DOI:10.1093/ije/dyi174 |

2023, Vol. 44

2023, Vol. 44