文章信息

- 王凯琳, 张淼, 李青, 阚慧, 刘海燕, 牟育彤, 李宗光, 曹焱敏, 董遥, 胡安群, 郑英杰.

- Wang Kailin, Zhang Miao, Li Qing, Kan Hui, Liu Haiyan, Mu Yutong, Li Zongguang, Cao Yanmin, Dong Yao, Hu Anqun, Zheng Yingjie

- 妊娠期糖尿病与早产亚型之间的关联研究

- Association between gestational diabetes mellitus and preterm birth subtypes

- 中华流行病学杂志, 2023, 44(5): 809-815

- Chinese Journal of Epidemiology, 2023, 44(5): 809-815

- http://dx.doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn112338-20220927-00815

-

文章历史

收稿日期: 2022-09-27

2. 安徽省安庆市立医院妇产科, 安庆 246003;

3. 安徽省安庆市立医院检验科, 安庆 246003

2. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Anqing Prefectural Hospital, Anhui Province, Anqing 246003, China;

3. Department of Clinical Laboratory, Anqing Prefectural Hospital, Anhui Province, Anqing 246003, China

早产是指婴儿胎龄小于37周时出生[1]。我国早产率处于全球的中等水平,但近30年来我国早产率呈上升趋势,随着全面二孩政策的推出,我国早产率的增幅明显,早产儿数量庞大[2-5]。早产可分为医源性早产(iPTB)和自发性早产(sPTB)[早产临产(PTL)和未足月胎膜早破(PPROM)][6]。早产是一种多病因、复杂综合征[7-8],不同亚型的发生机制不同[9]。目前妊娠期糖尿病(GDM)与早产的关系研究虽然多[10-20],但大多未能区分出早产亚型。仅有少量的关于GDM与sPTB的报道,但尚未得到一致的结论[21-23]。因此有必要探讨GDM与早产亚型之间的关联,进一步探究GDM是影响胎膜早破还是提前启动分娩级联反应,从而为探讨GDM与早产的病因机制提供线索。

对象与方法1. 研究对象: 基于以医院为基础的孕妇队列[24],已通过复旦大学公共卫生学院医学研究伦理委员会审查(批准文号:IRB#2017-09-0636)。自2018年2月22日至2020年12月31日,招募前来安徽省安庆市立医院进行产前先天性缺陷筛查(产前筛查)的孕妇[孕早期(11~12周)或孕中期(15~20周)两个时间段,以孕中期为主]。符合纳入和排除标准的孕妇进入基线队列,纳入标准:孕周 < 28周;年龄≥18周岁的孕妇;有自行参与研究调查的条件及能力,且签署知情同意书。排除标准:患有严重的免疫系统、脏器性疾病;基线近4周内服用抗生素、抗真菌药。

2. 资料和生物标本的收集: 对孕妇进行问卷调查和生物标本的采集,形成基线孕妇人群:基线问卷包括孕周、年龄、民族、孕前BMI、文化程度、家庭经济满意度、孕前治疗史(包括疏通输卵管、促排卵药物、人工授精、试管婴儿)、高血压家族史、糖尿病家族史、孕产史(初次妊娠、剖宫产手术史、流产史)、基线疾病(牙周炎、阴道炎)、阴道冲洗习惯、阴道药物治疗史、两周内阴道出血、吸烟史、饮酒史、睡眠质量等信息;同时进行生物标本的采集,包括阴道拭子和产前筛查血液经检测后的余留样本,按照生物标本常规进行分离和保存。

在孕期(部分孕妇)及妊娠结束后(全部孕妇)进行随访和生物标本采集,建设孕妇队列;至2021年7月全部孕妇已随访结束。随访方式:①在安庆市立医院分娩或妊娠终止者,其分娩结局、孕期并发症、实验室检测等相关信息从医院获取;②未在安庆市立医院分娩或妊娠终止者,在孕妇预产期后首先通过电话随访,获取其分娩医院及基本分娩信息,接着对孕妇分娩所在的安庆市及其辖区、县内的主要医院进行上门获取相关信息。主要获得的信息来源包括医院电子病历、产前记录手册、调查问卷等。若孕妇在妊娠期间前往安庆市立医院再次就诊,则对其进行随访和生物标本采集。

3. GDM和早产分类的判定: GDM定义为满足FPG≥5.1 mmol/L、餐后1 h血糖值≥10.0 mmol/L、餐后2 h血糖值≥8.5 mmol/L中任意一项[25]。早产定义为分娩时孕周在28~36周之间[26]。根据末次月经时间与分娩时间计算分娩时孕周,对于末次月经不详或月经不规律者则采用超声测得的胎儿双顶径数据推算孕周。

iPTB为因孕妇(如子痫前期、妊娠期肝内胆汁淤积)或胎儿合并严重并发症(如胎儿窘迫)而具有终止妊娠指征,人为提前终止妊娠[26];sPTB为无医源性分娩指征的早产,包括PTL和PPROM,其中PTL诊断标准为在37周前出现规律宫缩,同时伴有宫颈管缩短、宫颈进行性扩张;PPROM指在37周前胎膜在临产前发生自发性破裂,并最终在37周前分娩[7]。

所有判定按照我国诊疗规范进行[25-26],自医院获取诊断信息。

4. 统计学分析: 计量资料采用x±s或M(Q1,Q3)的形式进行描述,使用t检验或非参数检验进行变量的组间比较;分类资料采用例数及百分比(%)的形式进行描述,使用χ2检验或Fisher精确检验进行变量的组间比较。采用单因素log-binomial回归模型分析计算GDM与早产亚型之间的粗风险比(RR)及95%CI;根据既往文献资料判断可能的混杂因素[7, 27-30],结合可能的混杂因素分布情况,采用log-binomial回归模型分析调整潜在的混杂因素[31];对于多个混杂因素,采用倾向性评分校正法建立包含混杂因素的logistic回归模型,计算倾向评分[32],最终将倾向评分作为连续变量纳入log-binomial回归模型,以得到GDM与早产亚型之间调整混杂因素后的风险比(aRR)及95%CI。双侧检验,检验水准α=0.05。数据分析在SAS 9.4软件中进行。

结果1. 一般情况: 共纳入孕妇2 232例,有2 085例随访至结局,失访率为6.59%。在此基础上进一步排除:多胎妊娠(8例);已经被诊断为孕前糖尿病(14例);未分娩,包括流产(18例)、引产(14例),最终纳入分析的孕妇为2 031例。

2. 孕妇基线特征: 在纳入分析的2 031例单胎分娩的孕妇中,GDM和早产的发生比例分别为10.0%(204/2 031)和4.4%(90/2 031)。90例早产中,54.5%(49例)为PPROM,24.4%(22例)为PTL,21.1%(19例)为iPTB。

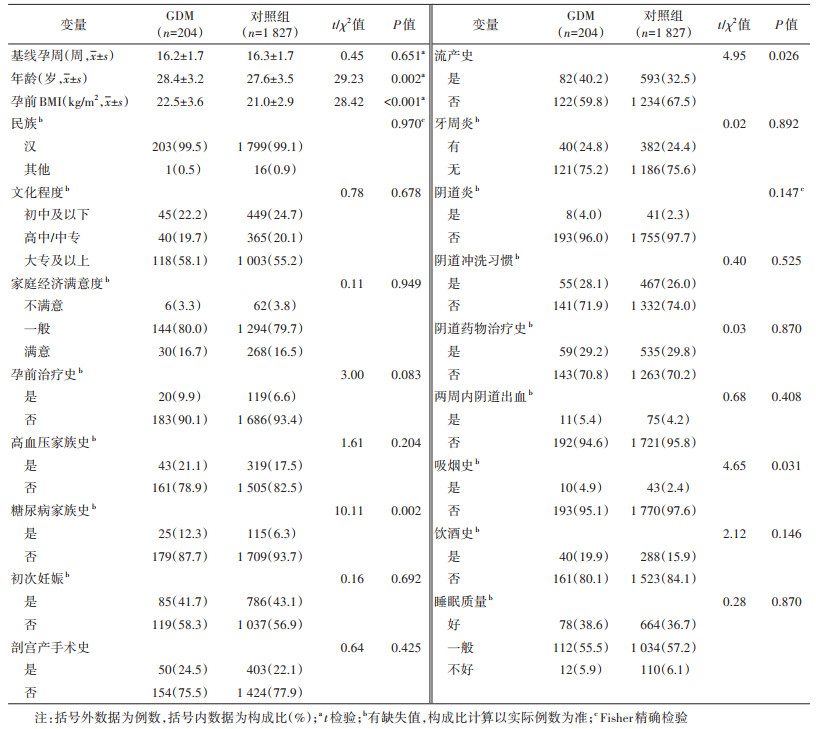

与非GDM孕妇相比,GDM孕妇年龄和孕前BMI相对较大,糖尿病家族史、流产史和吸烟史的占比相对较高,差异均有统计学意义(P < 0.05);其他变量的分布在两组间差异均无统计学意义。见表 1。

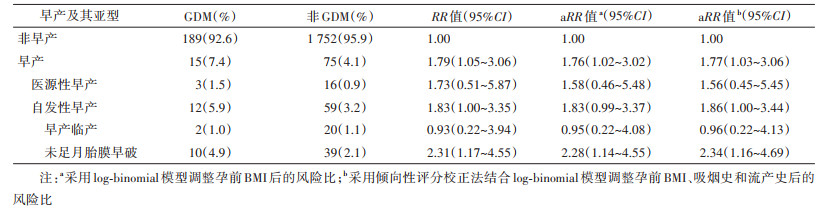

3. GDM与早产及其亚型间的关联: GDM组(n=204)孕妇发生iPTB和sPTB的比例分别为1.5%和5.9%,非GDM组(n=1 827)孕妇发生iPTB和sPTB的比例分别为0.9%和3.2%,sPTB的比例差异有统计学意义(P=0.048),iPTB的比例差异无统计学意义(P=0.176)。进一步细化sPTB亚型,结果显示GDM组发生PPROM、PTL的比例分别为4.9%和1.0%,非GDM组发生PPROM、PTL的比例分别为2.1%和1.1%。GDM孕妇发生PPROM的风险是非GDM孕妇的2.34倍(aRR=2.34,95%CI:1.16~4.69);GDM与PTL的发生无统计学关联。见表 2。

GDM与早产间的关系已有较多研究,通常在GDM与不良妊娠结局的关系研究中提及,且大多不区分早产的亚型(如iPTB、PPROM、PTL),多数研究者倾向于认为GDM是早产的危险因素[1]。本研究也发现GDM组的早产风险增加。一般来说,GDM可增加sPTB的发生风险[21, 33-34],该结果得到本研究的支持。亦有学者如Yogev和Langer[23]认为GDM与sPTB的发生风险无关,然而该研究中sPTB发生比例较高,这可能与研究的孕妇人群不同有关。

当前产科疾病的分类主要是基于非特异性的症状和体征,而从病因学和致病机制的角度来探讨疾病分类应更为合理[35-38]。早产系诊断于孕37周前分娩的事件,是一种复杂的、异质性较高、多机制的综合征,通常认为早产的发生系由子宫肌收缩、胎膜早破和宫颈成熟等引发[39-40]。其中iPTB因有明确的指征,临床上对其防控的策略明确,而对于sPTB则无对应的办法。sPTB中,孕妇产程启动按照首先发生胎膜破裂还是宫缩,区分出PPROM和PTL,通常前者占比不会比后者高,而本研究中PPROM的比例高于PTL。基于此,本研究分析了GDM与PPROM及PTL的关系发现,GDM孕妇可增加PPROM发生风险,而与PTL的发生无统计学关联。这与已有研究结果一致[41-43]。

虽然同为sPTB,PPROM和PTL发生的直接起因有所不同:胎膜的张力下降是胎膜早破发生的直接原因,主要由基质金属蛋白酶(MMP)介导的胎膜胶原蛋白降解引起。孕晚期雌激素水平下降可使MMP活性升高,加速胶原蛋白分解[44-48];而自发性宫缩的发生由前列腺素的上调直接引发,前列腺素可促使子宫平滑肌收缩,产生规律的宫缩,从而引起产程发动[49-50]。此外,正常妊娠状态下的胎膜各层均有微小的孔隙,被称为微骨折。研究发现,PPROM的胎膜微骨折数多于PTL胎膜,其数量与足月分娩的胎膜相近[51]。同时,PPROM的胎膜端粒比PTL的胎膜端粒更短[52],具有明显的衰老和应激特征,提示慢性氧化应激及其所导致的衰老可能减缓了胶原蛋白的修复速度,使胎膜更易破裂[53-54]。这些证据均提示促使PPROM和PTL发生的生理病理过程不同。

本研究发现GDM显著增加PPROM的发生风险,而与PTL无关。GDM一方面可能通过高血糖影响胎膜组织中MMP表达,导致胎膜细胞外基质中胶原蛋白降解,已观察到GDM孕妇存在着MMP表达失衡[55-56];另一方面,GDM孕妇炎症生物标志物改变且增加了胎盘炎症风险[57-58],其血清白细胞介素-6(IL-6)、白细胞介素-8(IL-8)和胎盘IL-6、IL-8、肿瘤坏死因子α等细胞因子与健康孕妇之间差异有统计学意义(P < 0.05)[59],氧化应激水平增加[60]。高糖环境可通过以上两方面交互诱发胎膜的细胞凋亡,进而影响胎膜的完整性,导致胎膜弱化,最终过早破裂[61-64]。此外有研究提出,GDM患者高糖环境可能导致胎儿过度生长、羊水增多,最终引起腹压过大,胎膜受压增大,可能引起PPROM[43]。PTL主要表现为子宫收缩提前启动,受激素内分泌影响较大,研究显示GDM孕妇催产素水平与正常孕妇差异无统计学意义[65]。此外,在孕前糖尿病孕妇人群中已经观察到其子宫收缩幅度和持续时间显著降低,细胞内钙和钙离子通道表达减少,子宫肌肉含量减少,子宫肌层对催产素反应下降,这意味着孕前糖尿病孕妇人群的子宫收缩力下降[66]。GDM与孕前糖尿病有相似的病理基础,因此GDM孕妇人群子宫收缩力也可能下降,这可能是GDM与PTL无统计学关联的原因之一。GDM引起的高糖环境如何影响MMP表达、羊水量以及细胞因子表达的具体分子通路仍有待进一步研究,GDM与子宫收缩的关系仍需深入探索。

本研究存在局限性。①本研究基于医院孕妇队列的基础上开展,原队列排除了近4周服用抗生素的孕妇和患有相关基础疾病的孕妇,因此相较于孕妇的源人群而言,该队列纳入研究的孕妇基线相对健康。②本研究原队列系单中心、中等样本量的研究,无法达到通过电子化孕妇保健数据库进行数据收集的高样本量,由本研究队列所获得的结局如iPTB和PTL的例数较少,从而出现关联估计值的方差较大,统计效能较低,可能影响其结果的稳定性。保持目前发生比例的情况下,当队列样本量分别达到26 200、45 531例方可达到80%的统计效能[67]。这些问题有赖于多中心、大样本量的进一步验证。

综上所述,本研究发现GDM可能增加PPROM的发生风险,可能与PTL无关。这提示,对GDM孕妇应当加强监测胎膜早破的发生,及时采取防治措施,关注GDM孕妇代谢、羊水量、炎症等指标的变化,做到早预防、早干预、早治疗。高糖如何影响胎膜早破的生物学机制仍需进一步研究。

利益冲突 所有作者声明无利益冲突

作者贡献声明 王凯琳:研究设计、实施研究、数据整理、统计分析、论文撰写;张淼、李青、阚慧、刘海燕、牟育彤、李宗光、曹焱敏、董遥:实施研究、数据收集、论文修改;胡安群、郑英杰:研究指导、论文修改、经费支持

| [1] |

Walani SR. Global burden of preterm birth[J]. Int J Gynecol Obstet, 2020, 150(1): 31-33. DOI:10.1002/ijgo.13195 |

| [2] |

Deng K, Liang J, Mu Y, et al. Preterm births in China between 2012 and 2018: an observational study of more than 9 million women[J]. Lancet Glob Health, 2021, 9(9): e1226-1241. DOI:10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00298-9 |

| [3] |

Jing SW, Chen C, Gan YX, et al. Incidence and trend of preterm birth in China, 1990-2016: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. BMJ Open, 2020, 10(12): e039303. DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039303 |

| [4] |

Chawanpaiboon S, Vogel JP, Moller AB, et al. Global, regional, and national estimates of levels of preterm birth in 2014: a systematic review and modelling analysis[J]. Lancet Glob Health, 2019, 7(1): e37-46. DOI:10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30451-0 |

| [5] |

Hu CY, Li FL, Jiang W, et al. Pre-pregnancy health status and risk of preterm birth: a large, Chinese, rural, population-based study[J]. Med Sci Monit, 2018, 24: 4718-4727. DOI:10.12659/MSM.908548 |

| [6] |

Vogel JP, Chawanpaiboon S, Moller AB, et al. The global epidemiology of preterm birth[J]. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol, 2018, 52: 3-12. DOI:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2018.04.003 |

| [7] |

Goldenberg RL, Culhane JF, Iams JD, et al. Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth[J]. Lancet, 2008, 371(9606): 75-84. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60074-4 |

| [8] |

Frey HA, Klebanoff MA. The epidemiology, etiology, and costs of preterm birth[J]. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med, 2016, 21(2): 68-73. DOI:10.1016/j.siny.2015.12.011 |

| [9] |

Goldenberg RL, Gravett MG, Iams J, et al. The preterm birth syndrome: issues to consider in creating a classification system[J]. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 2012, 206(2): 113-118. DOI:10.1016/j.ajog.2011.10.865 |

| [10] |

Nordin NM, Wei JWH, Naing NN, et al. Comparison of maternal-fetal outcomes in gestational diabetes and lesser degrees of glucose intolerance[J]. J Obstet Gynaecol Res, 2006, 32(1): 107-114. DOI:10.1111/j.1447-0756.2006.00360.x |

| [11] |

Cosson E, Vicaut E, Sandre-Banon D, et al. Initially untreated fasting hyperglycaemia in early pregnancy: prognosis according to occurrence of gestational diabetes mellitus after 22 weeks' gestation: a case-control study[J]. Diabet Med, 2020, 37(1): 123-130. DOI:10.1111/dme.14141 |

| [12] |

Martino J, Sebert S, Segura MT, et al. Maternal body weight and gestational diabetes differentially influence placental and pregnancy outcomes[J]. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2016, 101(1): 59-68. DOI:10.1210/jc.2015-2590 |

| [13] |

Gestation and Diabetes in France Study Group. Multicenter survey of diabetic pregnancy in France[J]. Diabetes Care, 1991, 14(11): 994-1000. DOI:10.2337/diacare.14.11.994 |

| [14] |

Soliman A, Salama H, Al Rifai H, et al. The effect of different forms of dysglycemia during pregnancy on maternal and fetal outcomes in treated women and comparison with large cohort studies[J]. Acta Biomed, 2018, 89(S5): 11-21. DOI:10.23750/abm.v89iS4.7356 |

| [15] |

Zhao D, Yuan SS, Ma Y, et al. Associations of maternal hyperglycemia in the second and third trimesters of pregnancy with prematurity[J]. Medicine (Baltimore), 2020, 99(17): e19663. DOI:10.1097/MD.0000000000019663 |

| [16] |

Sendag F, Terek MC, Itil IM, et al. Maternal and perinatal outcomes in women with gestational diabetes mellitus as compared to nondiabetic controls[J]. J Reprod Med, 2001, 46(12): 1057-1062. |

| [17] |

Yang XL, Hsu-Hage B, Zhang H, et al. Women with impaired glucose tolerance during pregnancy have significantly poor pregnancy outcomes[J]. Diabetes Care, 2002, 25(9): 1619-1624. DOI:10.2337/diacare.25.9.1619 |

| [18] |

HAPO Study Cooperative Research Group, Metzger BE, Lowe LP, et al. Hyperglycemia and adverse pregnancy outcomes[J]. N Engl J Med, 2008, 358(19): 1991-2002. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa0707943 |

| [19] |

Li MF, Ma L, Yu TP, et al. Adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes in pregnant women with abnormal glucose metabolism[J]. Diabetes Res Clin Pract, 2020, 161: 108085. DOI:10.1016/j.diabres.2020.108085 |

| [20] |

Billionnet C, Mitanchez D, Weill A, et al. Gestational diabetes and adverse perinatal outcomes from 716 152 births in France in 2012[J]. Diabetologia, 2017, 60(4): 636-644. DOI:10.1007/s00125-017-4206-6 |

| [21] |

Hedderson MM, Ferrara A, Sacks DA. Gestational diabetes mellitus and lesser degrees of pregnancy hyperglycemia: association with increased risk of spontaneous preterm birth[J]. Obstet Gynecol, 2003, 102(4): 850-856. DOI:10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00661-6 |

| [22] |

Köck K, Köck F, Klein K, et al. Diabetes mellitus and the risk of preterm birth with regard to the risk of spontaneous preterm birth[J]. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med, 2010, 23(9): 1004-1008. DOI:10.3109/14767050903551392 |

| [23] |

Yogev Y, Langer O. Spontaneous preterm delivery and gestational diabetes: the impact of glycemic control[J]. Arch Gynecol Obstet, 2007, 276(4): 361-365. DOI:10.1007/s00404-007-0359-8 |

| [24] |

Fan W, Kan H, Liu HY, et al. Association between human genetic variants and the vaginal bacteriome of pregnant women[J]. mSystems, 2021, 6(4): e0015821. DOI:10.1128/mSystems.00158-21 |

| [25] |

中华医学会妇产科学分会产科学组, 中华医学会围产医学分会妊娠合并糖尿病协作组. 妊娠合并糖尿病诊治指南(2014)[J]. 中华妇产科杂志, 2004, 49(8): 561-569. Obstetrics Group of Obstetrics and Gynecology Branch of Chinese Medical Association, Perinatology Branch of Chinese Medical Association Collaborative Group of Pregnancy and Diabetes. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of diabetes mellitus in pregnancy (2014)[J]. Chin J Obstet Gynecol, 2004, 49(8): 561-569. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0529-567x.2014.08.001 |

| [26] |

中华医学会妇产科学分会产科学组. 早产临床诊断与治疗指南(2014)[J]. 中华围产医学杂志, 2015, 18(4): 241-245. Obstetrics Group of Obstetrics and Gynecology Branch of Chinese Medical Association. Guidelines for clinical diagnosis and treatment of preterm birth (2014)[J]. Chin J Perinat Med, 2015, 18(4): 241-245. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1007-9408.2015.04.01 |

| [27] |

Liu BY, Xu GF, Sun YB, et al. Association between maternal pre-pregnancy obesity and preterm birth according to maternal age and race or ethnicity: a population-based study[J]. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol, 2019, 7(9): 707-714. DOI:10.1016/S2213-8587(19)30193-7 |

| [28] |

Swingle HM, Colaizy TT, Zimmerman MB, et al. Abortion and the risk of subsequent preterm birth: a systematic review with meta-analyses[J]. J Reprod Med, 2009, 54(2): 95-108. |

| [29] |

Ion R, Bernal AL. Smoking and preterm birth[J]. Reprod Sci, 2015, 22(8): 918-926. DOI:10.1177/1933719114556486 |

| [30] |

Gorgui J, Sheehy O, Trasler J, et al. Medically assisted reproduction and the risk of preterm birth: a case-control study using data from the Quebec Pregnancy Cohort[J]. CMAJ Open, 2020, 8(1): e206-213. DOI:10.9778/cmajo.20190082 |

| [31] |

Blizzard L, Hosmer W. Parameter estimation and goodness-of-fit in log binomial regression[J]. Biom J, 2006, 48(1): 5-22. DOI:10.1002/bimj.200410165 |

| [32] |

Heinze G, Jüni P. An overview of the objectives of and the approaches to propensity score analyses[J]. Eur Heart J, 2011, 32(14): 1704-1708. DOI:10.1093/eurheartj/ehr031 |

| [33] |

卢芷兰, 高崚, 程湘. 妊娠糖尿病血糖水平对孕妇及胎儿影响的研究[J]. 河北医学, 2014, 20(8): 1237-1240. Lu ZL, Gao L, Cheng X. Study on the effect of gestational diabetes glucose levels on pregnant woman and fetus[J]. Hebei Med, 2014, 20(8): 1237-1240. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1006-6233.2014.08.002 |

| [34] |

王丽丽. 妊娠期糖尿病孕妇血糖控制对妊娠结局的影响分析[J]. 中国妇幼保健, 2012, 27(34): 5473-5475. Wang LL. Analysis on the effect of glycemic control of pregnant women with gestational diabetes mellitus on pregnancy outcome[J]. Mater Child Health Care China, 2012, 27(34): 5473-5475. |

| [35] |

Romero R, Jung E, Chaiworapongsa T, et al. Toward a new taxonomy of obstetrical disease: improved performance of maternal blood biomarkers for the great obstetrical syndromes when classified according to placental pathology[J]. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 2022, 227(4): 615.e1-615.e25. DOI:10.1016/j.ajog.2022.04.015 |

| [36] |

Roura LC, Hod M. Identification, prevention, and monitoring of the "great obstetrical syndromes"[J]. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol, 2015, 29(2): 145-149. DOI:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2014.10.001 |

| [37] |

Di Renzo GC. The great obstetrical syndromes[J]. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med, 2009, 22(8): 633-635. DOI:10.1080/14767050902866804 |

| [38] |

Gabbay-Benziv R, Baschat AA. Gestational diabetes as one of the "great obstetrical syndromes"-the maternal, placental, and fetal dialog[J]. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol, 2015, 29(2): 150-155. DOI:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2014.04.025 |

| [39] |

Di Renzo GC, Tosto V, Giardina I. The biological basis and prevention of preterm birth[J]. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol, 2018, 52: 13-22. DOI:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2018.01.022 |

| [40] |

Romero R, Dey SK, Fisher SJ. Preterm labor: one syndrome, many causes[J]. Science, 2014, 345(6198): 760-765. DOI:10.1126/science.1251816 |

| [41] |

Bouvier D, Forest JC, Blanchon L, et al. Risk factors and outcomes of preterm premature rupture of membranes in a cohort of 6 968 pregnant women prospectively recruited[J]. J Clin Med, 2019, 8(11): 1987. DOI:10.3390/jcm8111987 |

| [42] |

Sae-Lin P, Wanitpongpan P. Incidence and risk factors of preterm premature rupture of membranes in singleton pregnancies at Siriraj Hospital[J]. J Obstet Gynaecol Res, 2019, 45(3): 573-577. DOI:10.1111/jog.13886 |

| [43] |

刘姣, 赵明阳, 梁弘, 等. 未足月胎膜早破危险因素Meta分析[J]. 中国预防医学杂志, 2022, 23(1): 44-50. Liu J, Zhao MY, Liang H, et al. Risk factors associated with preterm premature rupture of membranes: a Meta analysis[J]. Chin Prev Med, 2022, 23(1): 44-50. DOI:10.16506/j.1009-6639.2022.01.008 |

| [44] |

Tjugum J, Norström A. The influence of prostaglandin E2 and oxytocin on the incorporation of [3H]proline and [3H]glucosamine in the human amnion[J]. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol, 1985, 19(3): 137-143. DOI:10.1016/0028-2243(85)90147-9 |

| [45] |

Lei HQ, Vadillo-Ortega F, Paavola LG, et al. 92-kDa gelatinase (matrix metalloproteinase-9) is induced in rat amnion immediately prior to parturition[J]. Biol Reprod, 1995, 53(2): 339-344. DOI:10.1095/biolreprod53.2.339 |

| [46] |

Lei H, Furth EE, Kalluri R, et al. A program of cell death and extracellular matrix degradation is activated in the amnion before the onset of labor[J]. J Clin Invest, 1996, 98(9): 1971-1978. DOI:10.1172/JCI119001 |

| [47] |

Bryant-Greenwood GD, Mamamoto SY. Control of peripartal collagenolysis in the human chorion-decidua[J]. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 1995, 172(1): 63-70. DOI:10.1016/0002-9378(95)90085-3 |

| [48] |

Sato T, Ito A, Mori Y, et al. Hormonal regulation of collagenolysis in uterine cervical fibroblasts. Modulation of synthesis of procollagenase, prostromelysin and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases (TIMP) by progesterone and oestradiol-17 β[J]. Biochem J, 1991, 275(3): 645-650. DOI:10.1042/bj2750645 |

| [49] |

Young RC. The uterine pacemaker of labor[J]. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol, 2018, 52: 68-87. DOI:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2018.04.002 |

| [50] |

Wray S. Uterine contraction and physiological mechanisms of modulation[J]. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol, 1993, 264(1 Pt 1): C1-18. DOI:10.1152/ajpcell.1993.264.1.C1 |

| [51] |

Bond DM, Middleton P, Levett KM, et al. Planned early birth versus expectant management for women with preterm prelabour rupture of membranes prior to 37 weeks' gestation for improving pregnancy outcome[J]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2017, 3(3): Cd004735. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD004735.pub4 |

| [52] |

Menon R, Richardson LS, Lappas M. Fetal membrane architecture, aging and inflammation in pregnancy and parturition[J]. Placenta, 2019, 79: 40-45. DOI:10.1016/j.placenta.2018.11.003 |

| [53] |

Menon R, Boldogh I, Hawkins HK, et al. Histological evidence of oxidative stress and premature senescence in preterm premature rupture of the human fetal membranes recapitulated in vitro[J]. Am J Pathol, 2014, 184(6): 1740-1751. DOI:10.1016/j.ajpath.2014.02.011 |

| [54] |

Menon R. Oxidative stress damage as a detrimental factor in preterm birth pathology[J]. Front Immunol, 2014, 5: 567. DOI:10.3389/fimmu.2014.00567 |

| [55] |

Menon R, Fortunato SJ. Infection and the role of inflammation in preterm premature rupture of the membranes[J]. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol, 2007, 21(3): 467-478. DOI:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2007.01.008 |

| [56] |

Zuo G, Dong JX, Zhao FF, et al. Expression of matrix metalloproteinase-9 and its substrate level in patients with premature rupture of membranes[J]. J Obstet Gynaecol, 2017, 37(4): 441-445. DOI:10.1080/01443615.2016.1250734 |

| [57] |

Pan X, Jin X, Wang J, et al. Placenta inflammation is closely associated with gestational diabetes mellitus[J]. Am J Transl Res, 2021, 13(5): 4068-4079. |

| [58] |

Li YX, Long DL, Liu J, et al. Gestational diabetes mellitus in women increased the risk of neonatal infection via inflammation and autophagy in the placenta[J]. Medicine (Baltimore), 2020, 99(40): e22152. DOI:10.1097/MD.0000000000022152 |

| [59] |

Zhang J, Chi HY, Xiao HY, et al. Interleukin 6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), Inflammation and metabolism in gestational diabetes mellitus in Inner Mongolia[J]. Med Sci Monit, 2017, 23: 4149-4157. DOI:10.12659/msm.903565 |

| [60] |

Li HW, Yin Q, Li N, et al. Plasma markers of oxidative stress in patients with gestational diabetes mellitus in the second and third trimester[J]. Obstet Gynecol Int, 2016, 2016, 3865454. DOI:10.1155/2016/3865454 |

| [61] |

Keelan JA, Blumenstein M, Helliwell RJA, et al. Cytokines, prostaglandins and parturition-a review[J]. Placenta, 2003, 24(Suppl A): S33-46. DOI:10.1053/plac.2002.0948 |

| [62] |

Uchide N, Ohyama K, Bessho T, et al. Induction of pro-inflammatory cytokine gene expression and apoptosis in human chorion cells of fetal membranes by influenza virus infection: possible implications for maintenance and interruption of pregnancy during infection[J]. Med Sci Monit, 2005, 11(1): RA7-16. |

| [63] |

Menon R, Lombardi SJ, Fortunato SJ. TNF-α promotes caspase activation and apoptosis in human fetal membranes[J]. J Assist Reprod Genet, 2002, 19(4): 201-204. DOI:10.1023/a:1014898130008 |

| [64] |

Kumar D, Fung W, Moore RM, et al. Proinflammatory cytokines found in amniotic fluid induce collagen remodeling, apoptosis, and biophysical weakening of cultured human fetal membranes[J]. Biol Reprod, 2006, 74(1): 29-34. DOI:10.1095/biolreprod.105.045328 |

| [65] |

Stock S, Bremme K, Uvnäs-Moberg K. Is oxytocin involved in the deterioration of glucose tolerance in gestational diabetes?[J]. Gynecol Obstet Invest, 1993, 36(2): 81-86. DOI:10.1159/000292601 |

| [66] |

Al-Qahtani S, Heath A, Quenby S, et al. Diabetes is associated with impairment of uterine contractility and high Caesarean section rate[J]. Diabetologia, 2012, 55(2): 489-498. DOI:10.1007/s00125-011-2371-6 |

| [67] |

Hill JB, Sheffield JS, Kim MJ, et al. Risk of hepatitis B transmission in breast-fed infants of chronic hepatitis B carriers[J]. Obstet Gynecol, 2002, 99(6): 1049-1052. DOI:10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02000-8 |

2023, Vol. 44

2023, Vol. 44