文章信息

- 王展, 王文瑾, 丁晓艳, 卢鹏, 竺丽梅, 刘巧, 陆伟.

- Wang Zhan, Wang Wenjin, Ding Xiaoyan, Lu Peng, Zhu Limei, Liu Qiao, Lu Wei

- 利福平耐药结核病患者接触者预防性治疗研究进展

- Progress in research of prophylactic therapy in contacts of rifampicin-resistant tuberculosis patients

- 中华流行病学杂志, 2023, 44(3): 470-476

- Chinese Journal of Epidemiology, 2023, 44(3): 470-476

- http://dx.doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn112338-20220729-00673

-

文章历史

收稿日期: 2022-07-29

2. 南京医科大学公共卫生学院流行病学系, 南京 211166

2. Department of Epidemiology for School of Public Health, Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing 211166, China

结核病(tuberculosis,TB)是由结核分枝杆菌引起的慢性传染性疾病。根据2021年WHO报告结果显示,2020年全球估算新发结核病患者数为990万例,其中中国占8.5%,位居全球第二位,仅次于印度[1]。WHO估算全球约有23%的人口(近17亿)感染了结核分枝杆菌[2],其中我国有近3.6亿结核分枝杆菌感染者,是全球结核潜伏感染(latent tuberculosis infection,LTBI)负担较重的国家之一[3]。我国是耐多药/利福平耐药结核病(multi-drug and rifampicin-resistant tuberculosis,MDR/RR-TB)高负担国家,由于MDR/RR-TB治疗时间长、治疗效果差、治疗成本高,因此MDR/RR-TB已成为结核病防治工作的巨大挑战[4]。虽然目前发现和治疗MDR/RR-TB是控制MDR/RR-TB的首要选择,但是单靠这一方法将不足以实现2035年终结结核病战略目标[5]。减少LTBI,对LTBI开展抗结核预防性治疗,已被证实是防止结核病发生的一项非常有效的手段,是从源头上控制MDR/RR-TB的重要措施[6-8]。目前对接触MDR/RR-TB的感染者还没有统一的预防性治疗方案,本文通过查找文献、指南、专家共识和技术规范,对MDR/RR-TB预防性治疗方案和保护效果进行综述,以期为LTBI的防控提供参考依据。

1. MDR/RR-TB流行现状:结核病是可治愈和预防的,约85%的药物敏感结核病患者通过6个月的联合药物方案治疗成功。但耐药结核病仍然是威胁人类健康的公共卫生问题,MDR/RR-TB指结核分枝杆菌感染对利福平或异烟肼和利福平联用均有耐药性,MDR/RR-TB患者治疗时间更长,治疗成功率低,如果未被及时发现和充分治疗,则会导致治疗失败、高死亡率和长期社区传播[9],也是终结结核病战略目标难以实现的主要障碍之一。2019年全球约有46.5万MDR/RR-TB患者,占新结核病患者的3.3%,占复治结核病患者的18%[2]。2019年我国新增MDR/RR-TB病例数约6.6万,位居全球第二位,占全球新增MDR/RR-TB病例总数的14%。在我国约7.6%的结核病患者为MDR/RR-TB患者,7.1%的初治患者和21.0%的复治患者为MDR/RR-TB患者,三大比例均明显高于全球平均水平[2]。2020年全球仅有150 359例MDR/RR-TB患者登记接受治疗,比2019年的总数(177 100例)下降了15%,登记接受治疗的人数出现逆转,意味着联合国高级别会议设定的全球目标似乎难以达到。2018-2020年,报告登记接受治疗的MDR/RR-TB患者总数为482 683例,仅为5年目标(1 500 000例)的32%,特别是儿童MDR/RR-TB患者,累计12 219例,仅为5年目标(115 000例)的11%[1]。

2. LTBI和预防性治疗:结核分枝杆菌感染人体后,根据结核分枝杆菌感染状态可以分为3种结局:未感染结核分枝杆菌、感染结核分枝杆菌未发病和活动性肺结核[10]。在活动性结核病之前存在一个临床状态,即LTBI。它是机体无活动性结核临床表现的一种持续免疫应答状态[11-12],但人体免疫力低下时结核分枝杆菌可以继续复制,导致LTBI进展为活动性结核病患者,并成为新的传染源。相对于没有感染的人,LTBI发病风险增加,一生中发展成为结核病患者的可能性为5%~10%,尤其在感染后的1~2年内[13]。

既往研究表明,对LTBI人群开展预防性治疗,其保护效果可达60%~90%[14]。异烟肼预防性治疗是广泛使用的结核病预防治疗方法,但利福霉素治疗方案的持续时间较短,治疗依从性高。WHO推荐的预防性治疗方案包括:3个月的利福喷汀与异烟肼联合使用,每周服用1次;3个月的利福平与异烟肼联合使用(3HR),每日1次;1个月的利福喷汀与异烟肼联合使用,每日1次;4个月的利福平,每日1次;6个月的异烟肼,每日1次或更长时间[1]。美国胸科协会和美国CDC提出的预防性治疗方案为9个月的异烟肼[15]。《中国结核病防治规划实施工作指南(2021年版)》推荐使用的结核病预防性治疗方案包括单用异烟肼治疗6~9个月(每日1次);异烟肼和利福喷汀联用3个月(每周服药2次);3HR(每日1次);单用利福平4个月方案(每日1次以及免疫制剂方案)[16]。

Zenner等[14]一项系统回顾也显示,与服用安慰剂的参与者相比,接受6个月预防性治疗后结核病发病率明显下降(OR=0.65,95%CI:0.50~0.83)。Comstock等[17]的研究表明,单纯异烟肼预防性治疗的保护效果可持续19年,如果没有再次感染,可能维持终身。Comstock[18]的研究表明,异烟肼治疗9个月后,有效率可达到90%。Pape等[19]的研究表明,12个月的异烟肼治疗有明显的保护作用(RR=0.29,95%CI:0.09~0.91)。翁丽霞和王勇[20]在湖北省开展一项预防性治疗的随机对照试验,干预组预防性治疗方案为3HR,对照组为空白对照,随访1年后,干预组未出现活动性结核病病例,而对照组发病率为24.73%。戴景涛和卓玛[21]开展了3HR的临床随机对照试验,随访2年后,干预组的发病率为2%,对照组发病率为10%,两组发病率的差异有统计学意义(P < 0.05)。

3. MDR/RR-TB预防性治疗方案研究进展:当前,全人群的LTBI检测和预防性治疗显然不可行。因此,结核病预防性治疗应针对那些具有发展为活动性结核病高风险的人群[22]。系统综述和荟萃分析表明,接触MDR/RR-TB患者的LTBI者患结核病的风险较高,通常在接触后1~2年内确诊[23]。LTBI者预防性治疗在控制MDR/RR-TB方面具有重要作用,并且有证据表明其能降低结核病发病风险[24-25]。许多国际机构和专家还建议,对MDR/RR-TB患者接触者预防性治疗的研究应成为全球公共卫生研究的重点[26-27]。一项系统回顾显示,耐多药结核病患者接触者中的LTBI者预防性治疗后,耐多药结核病的发病率约降低90%[28]。对耐多药结核病患者接触者进行有针对性地预防性治疗的潜在好处大于危害,但由于缺乏随机对照试验,干预措施的效果存在不确定性[25]。

WHO建议在MDR-TB患者接触者中使用氟喹诺酮类药物进行预防性治疗,联合左氧氟沙星和其他抗结核药物(如乙胺丁醇或乙硫酰胺)使用6个月,无论是否接受预防性治疗,都开展2年的临床随访。对RR-TB患者接触者可进行与MDR-TB患者接触者类似的预防性治疗[29]。美国胸科学会和美国CDC建议吡嗪酰胺与乙胺丁醇或氟喹诺酮联合使用方案,开展MDR-TB患者接触者预防性治疗[30]。美国加利福尼亚州公共卫生部和Curry国际结核病中心建议采用使用左氧氟沙星或莫西沙星,并联合使用对患者分离株敏感的药物(乙胺丁醇、环丝氨酸、对氨基水杨酸等)[31]。美国胸科学会、欧洲呼吸学会和美国传染病学会共同发布的临床实践指南推荐单独使用新一代氟喹诺酮类药物或与乙胺丁醇等第2种抗结核药物联合使用[32]。美国CDC建议针对免疫力正常的MDR-TB患者接触者使用6个月或更长时间的吡嗪酰胺联合乙胺丁醇或者吡嗪酰胺联合左氧氟沙星方案;而对免疫力低下或者HIV阳性的接触者需要将时间延长至12个月甚至更长[15]。在欧盟国家中,有建议对耐多药结核病患者接触者进行至少2年的随访,有建议采取化学预防或后续行动,也有建议对进展为活动性结核病的高风险接触者进行化学预防,对进展风险较低的接触者进行随访跟踪[33]。新西兰卫生部建议对未接受治疗的MDR-TB患者接触者应每半年监测一次胸片随访接触者结核病发展情况,并持续2年[34]。印度研究对于利福平耐药而氟喹诺酮类药物敏感的结核病患者接触者采取6个月左氧氟沙星方案[35]。日本研究不建议对MDR-TB患者的接触者开展预防性治疗,认为对LTBI预防性治疗引起的耐药性可能进一步降低治愈的可能性。建议对MDR-TB患者接触者开展密切的随访观察,一旦发现LTBI进展为结核病患者立即提供恰当的治疗[36]。澳大利亚推荐单独使用至少6个月的氟喹诺酮类药物(莫西沙星或左氧氟沙星),或使用氟喹诺酮类药物联合使用另一种药物(如乙胺丁醇或丙硫酰胺)[37]。《中国结核病防治规划实施工作指南(2021年版)》推荐耐多药结核病的预防性治疗需要结合患者耐药情况,选择敏感药品组成方案对密切接触者进行预防性治疗[16]。

WHO报告结果显示,在RR-TB患者中同时耐氟喹诺酮类药物的患者占17.6%[38]。我国2010年全国耐药监测数据结果显示在MDR/RR-TB患者中同时耐氧氟沙星的患者比例为4.91%[39]。在MDR/RR-TB患者中约有5%~20%同时氟喹诺酮类药物耐药,即其接触者无法从含氟喹诺酮类药物的预防性服药方案中获益。如果有确切证据显示接触的患者除MDR/RR-TB外还耐氟喹诺酮类药物,则不建议接触者开展预防性治疗,建议密切随访2年以上。LTBI治疗前如果未能完全排除活动性结核病,可能增加对所使用药物的耐药性。但是目前预防性服药相关综述的结果显示,异烟肼或利福霉素预防性治疗的耐药风险并没有增加[40-42]。目前关于MDR/RR-TB患者接触者6个月氟喹诺酮类药物预防性治疗方案文献较少,是否增加耐药风险还未见相关文献报道。严格开展预防性治疗前医学评价并坚持完成预防性治疗疗程是获得良好保护效果的重要决定因素。

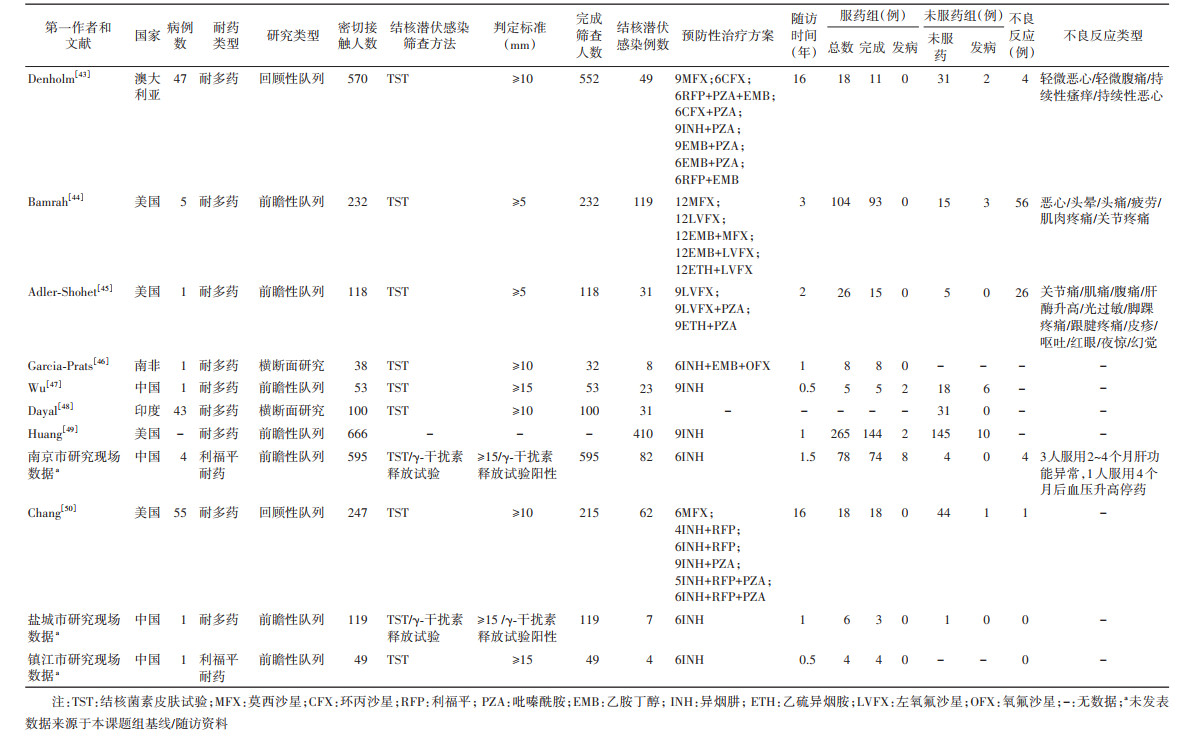

4. MDR/RR-TB预防性治疗效果研究进展:检索PubMed、Web of Science、中国知网、万方数据知识服务平台和江苏省结核病专报系统,以查找截至2021年12月发表的主要研究。纳入标准:①指示病例为经临床、影像学或实验室检查确诊为MDR/RR-TB患者;②有明确的预防性治疗方案;③有LTBI的筛查方法和诊断标准;④对接触者有随访。排除标准:①未提供研究类型或耐药类型;②重复发表的文献;③指示病例为非MDR/RR-TB患者。共纳入11项研究(已发表研究8项、未发表研究3项)[43-50],其中8项研究有服药组和未服药组发病情况,3项研究缺失服药组或未服药组发病情况。9项研究的指示病例为MDR-TB患者,2项研究的初始病例为RR-TB患者。11项研究纳入2 787例接触者和826例LTBI者,预防性治疗的532例LTBI者中,完成治疗375例(12例进展为活动性结核病);294例LTBI者未预防性治疗,其中22例进展为活动性结核病。Garcia-Prats等 [46]研究8例LTBI者,均进行了预防性治疗,尚无活动性结核病。Dayal等[48]一项描述性研究报告31例LTBI者,均未进行预防性治疗,尚无活动性结核病。91例治疗的患者报告了不良反应,主要为恶心和腹痛。见表 1。

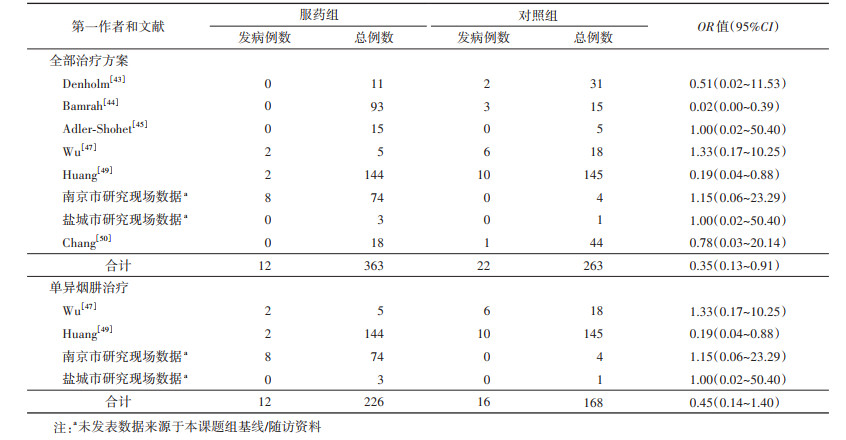

在有服药组和未服药组发病数据的8项研究中,固定效应模型分析的森林图结果显示,治疗组的发病率低于对照组(OR=0.35,95%CI:0.13~0.91)。Bamrah等[44]报告的119例LTBI者中,预防性治疗104例(完成治疗93例、尚无活动性结核病病例);未预防性治疗的15例中,3例发展为活动性结核病(OR=0.02,95%CI:0.00~0.39)。Huang等[49]报告的410例LTBI者中,预防性治疗265例(完成治疗144例、2例发展为活动性结核病);未预防性治疗的145例中,10例发展为活动性结核病(OR=0.19,95%CI:0.04~0.88)。4项研究使用单异烟肼对MDR/RR-TB患者接触者进行预防性治疗,共纳入LTBI者522例,预防性治疗354例(完成治疗226例、12例发展为活动性结核病);未开展预防性治疗的168例中,16例发展为活动性结核病,固定效应模型分析的森林图结果显示,治疗组的发病率低于对照组,差异无统计学意义(OR=0.45,95%CI:0.14~1.40)。见表 2。

5. 挑战与展望:随着2035年终结结核病战略目标的提出,各国已经开始认识到扩大预防性治疗的重要性。无论是在高流行和低流行地区,开展结核潜伏感染预防性治疗是实现这一愿景的关键组成部分。在MDR/RR-TB患者接触者中采用联合氟喹诺酮类二线药物的预防性治疗方案对LTBI者有保护作用,但是单纯的异烟肼方案作用不大。MDR/RR-TB患者接触者在开展化学预防性治疗前必须要经过当地权威专家组的讨论和决定,鉴于中断预防性服药的后果比不治疗更严重,建议对MDR/RR-TB患者接触者预防性服药采取直接面试下服药管理,并密切监测不良反应。无论是否开展预防性治疗,均建议每随访6个月开展1次胸部影像学检查,持续随访时间≥2年。除此之外,还需要持续优化MDR/RR-TB患者接触者预防性治疗方案的组成、剂量和持续时间,积极开发具有良好杀菌性能的新型药物,确定毒性更小和更可行的治疗策略。将来需要更多高质量的随机对照临床试验来进一步探索MDR/RR-TB患者接触者的预防性治疗方案和保护效果。

结核潜伏性感染预防性治疗的开展不能“一刀切”,需要综合风险群体发展为活动性结核病的可能性、结核病负担、资源的可及性以及公共卫生影响等多方面考虑。在结核病高负担地区由于结核病高患病率和高传播率,结核潜伏感染治疗效果持续时间依旧是个挑战,加上资源有限,实施结核病预防性治疗仍然是一个低优先级别。WHO管理指南中要求LTBI者管理的策略应包括识别高危人群、排除活动性结核病、检测LTBI、提供预防性治疗、监测不良事件、全程规范治疗和随访和评估。只有在充分评估患者的个人风险和收益基础上,对预防性治疗对象开展全程督导服药、监测和不良反应处理、提供必要的心理关怀等有效措施,才能提高预防性治疗对象的依从性,减少不规律用药和获得性耐药的风险,从而达到预期的预防性治疗效果。

利益冲突 所有作者声明无利益冲突

作者贡献声明 王展:采集数据、分析数据;王文瑾:采集数据;丁晓艳、卢鹏、竺丽梅:文章审阅、提供行政、技术和材料支持;刘巧、陆伟:文章审阅、提供经费、行政、技术和材料支持

| [1] |

WHO. Global tuberculosis report 2021[EB/OL]. (2021-10-14)[2022-07-02]. https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/1379788/retrieve.

|

| [2] |

WHO. Global tuberculosis report 2020[EB/OL]. (2020-10-14)[2022-07-02]. https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/1312164/retrieve.

|

| [3] |

李相威, 金奇, 高磊. 我国结核分枝杆菌潜伏感染流行现状[J]. 新发传染病电子杂志, 2017, 2(3): 146-150. Li XW, Jin Q, Gao L. A short review on the epidemiology of latent tuberculosis infection in China[J]. Electron J Emerg Infect Dis, 2017, 2(3): 146-150. DOI:10.19871/j.cnki.xfcrbzz.2017.03.005 |

| [4] |

肖和平. 耐药结核病化学治疗指南(2019年简版)[J]. 中国防痨杂志, 2019, 41(10): 1025-1073. Xiao HP. Guidelines for chemotherapy of drug-resistant tuberculosis (2019 edition)[J]. Chin J Antituberc, 2019, 41(10): 1025-1073. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1000-6621.2019.10.001 |

| [5] |

Fox GJ, Dobler CC, Marais BJ, et al. Preventive therapy for latent tuberculosis infection-the promise and the challenges[J]. Int J Infect Dis, 2017, 56: 68-76. DOI:10.1016/j.ijid.2016.11.006 |

| [6] |

Falzon D, Jaramillo E, Schünemann HJ, et al. WHO guidelines for the programmatic management of drug-resistant tuberculosis: 2011 update[J]. Eur Respir J, 2011, 38(3): 516-528. DOI:10.1183/09031936.00073611 |

| [7] |

Gilpin CM, Simpson G, Vincent S, et al. Evidence of primary transmission of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in the Western Province of Papua New Guinea[J]. Med J Aust, 2008, 188(3): 148-152. DOI:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2008.tb01557.x |

| [8] |

Deun AV, Maug AKJ, Salim MAH, et al. Short, highly effective, and inexpensive standardized treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis[J]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2010, 182(5): 684-692. DOI:10.1164/rccm.201001-0077OC |

| [9] |

Millard J, Ugarte-Gil C, Moore DAJ. Multidrug resistant tuberculosis[J]. BMJ, 2015, 350: h882. DOI:10.1136/bmj.h882 |

| [10] |

周枫. 两所医院医务人员结核分枝杆菌潜伏感染及防制策略研究[D]. 重庆: 第三军医大学, 2015. Zhou F. Study of latent tuberculosis infection and prevention strategy among health care workers in two hospitals[D]. Chongqing: Third Military Medical University, 2015. |

| [11] |

Getahun H, Matteelli A, Chaisson RE, et al. Latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection[J]. N Engl J Med, 2015, 372(22): 2127-2135. DOI:10.1056/NEJMra1405427 |

| [12] |

Jagger A, Reiter-Karam S, Hamada Y, et al. National policies on the management of latent tuberculosis infection: review of 98 countries[J]. Bull World Health Organ, 2018, 96(3): 173-184F. DOI:10.2471/BLT.17.199414 |

| [13] |

卢鹏, 成君, 路希维, 等. 科学开展预防性治疗加速遏制结核病进程[J]. 中国防痨杂志, 2020, 42(4): 316-321. Lu P, Cheng J, Lu XW, et al. Scientific preventive treatment to accelerate the process of tuberculosis control[J]. Chin J Antituberc, 2020, 42(4): 316-321. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1000-6621.2020.04.004 |

| [14] |

Zenner D, Beer N, Harris RJ, et al. Treatment of latent tuberculosis infection: an updated network Meta-analysis[J]. Ann Intern Med, 2017, 167(4): 248-255. DOI:10.7326/M17-0609 |

| [15] |

David L, Richard J. Targeted tuberculin testing and treatment of latent tuberculosis infection[J]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2000, 161(4 Pt 2): S221-247. DOI:10.1164/ajrccm.161.supplement_3.ats600 |

| [16] |

中国疾病预防控制中心结核病预防控制中心. 中国结核病防治规划实施工作指南(2021年版)[R]. 2021. Department of policy planning, National Center for Tuberculosis Control and Prevetion, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidelines for the implementation of tuberculosis prevention and control programs in China 2021 edition[R]. 2021. |

| [17] |

Comstock GW, Woolpert SF, Baum C. Isoniazid prophylaxis among Alaskan Eskimos: a progress report[J]. Am Rev Respir Dis, 1974, 110(2): 195-197. DOI:10.1164/arrd.1974.110.2.195 |

| [18] |

Comstock GW. How much isoniazid is needed for prevention of tuberculosis among immunocompetent adults?[J]. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis, 1999, 3(10): 847-850. |

| [19] |

Pape JW, Jean SS, Ho JL, et al. Effect of isoniazid prophylaxis on incidence of active tuberculosis and progression of HIV infection[J]. Lancet, 1993, 342(8866): 268-272. DOI:10.1016/0140-6736(93)91817-6 |

| [20] |

翁丽霞, 王勇. 学校涂阳肺结核密切接触者筛查及预防性服药效果分析[J]. 国际流行病学传染病学杂志, 2014, 41(4): 258-260. Weng LX, Wang Y. Screening close contacts of smear-positive tuberculosis patients and the effectiveness of preventive medication in close contacts in school[J]. Int J Epidemiol Infect Dis, 2014, 41(4): 258-260. DOI:10.3760/cma.issn.1673-4149.2014.04.011 |

| [21] |

戴景涛, 卓玛. 结核潜伏性感染预防性治疗效果分析[J]. 医药前沿, 2018, 8(31): 219-220. Dai JT, Zhuo M. Effect of prophylactic treatment on latent tuberculosis infection[J]. J Front of Med, 2018, 8(31): 219-220. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.2095-1752.2018.31.177 |

| [22] |

李果, 庞先琼, 徐华, 等. 潜伏性结核感染诊治进展[J]. 中国防痨杂志, 2021, 43(1): 91-95. Li G, Pang XQ, Xu H, et al. Progress in diagnosis and treatment of latent tuberculosis infection[J]. Chin J Antituberc, 2021, 43(1): 91-95. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1000-6621.2021.01.017 |

| [23] |

Fox GJ, Barry SE, Britton WJ, et al. Contact investigation for tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Eur Respir J, 2013, 41(1): 140-156. DOI:10.1183/09031936.00070812 |

| [24] |

Menzies D, Adjobimey M, Ruslami R, et al. Four months of rifampin or nine months of isoniazid for latent tuberculosis in adults[J]. N Engl J Med, 2018, 379(5): 440-453. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa1714283 |

| [25] |

WHO. Latent tuberculosis infection: updated and consolidated guidelines for programmatic management[EB/OL]. (2018-02-15)[2022-07-02]. https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/1095572/retrieve.

|

| [26] |

ECDC. Management of contacts of MDR TB and XDR TB patients[EB/OL]. (2012-05-20)[2022-07-02]. https://www.tbonline.info/media/uploads/documents/management_of_contacts_of_mdr_tb_and_xdr_tb_patients_%282012%29.pdf.

|

| [27] |

Cobelens FGJ, Heldal E, Kimerling ME, et al. Scaling up programmatic management of drug-resistant tuberculosis: a prioritized research agenda[J]. PLoS Med, 2008, 5(7): e150. DOI:10.1371/journal.pmed.0050150 |

| [28] |

Marks SM, Mase SR, Morris SB. Systematic review, meta-analysis, and cost-effectiveness of treatment of latent tuberculosis to reduce progression to multidrug-resistant tuberculosis[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2017, 64(12): 1670-1677. DOI:10.1093/cid/cix208 |

| [29] |

WHO. WHO operational handbook on tuberculosis[EB/OL]. (2020-05-22)[2022-07-02]. https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/1272664/retrieve.

|

| [30] |

American Thoracic Society. Targeted tuberculin testing and treatment of latent tuberculosis infection[J]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2000, 161(4 Pt 2): S221-247. DOI:10.1164/ajrccm.161.supplement_3.ats600 |

| [31] |

Curry International Tuberculosis Center and California Department of Public Health. Drug-resistant tuberculosis: a survival guide for clinicians, 3rd edition/2022 Updates[EB/OL]. (2016-10-25)[2022-07-02]. https://www.currytbcenter.ucsf.edu/products/view/drug-resistant- tuberculosis-survival-guide-clinicians-3rd-edition.

|

| [32] |

Nahid P, Mase SR, Migliori GB, et al. Treatment of drug-resistant tuberculosis. An official ATS/CDC/ERS/IDSA clinical practice guideline[J]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2019, 200(10): e93-142. DOI:10.1164/rccm.201909-1874ST |

| [33] |

van der Werf MJ, Sandgren A, Manissero D. Management of contacts of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis patients in the European Union and European Economic Area[J]. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis, 2012, 16(3): 426. DOI:10.5588/ijtld.11.0605 |

| [34] |

Ministry of Health. Guidelines for tuberculosis control in New Zealand 2019. Wellington: ministry of health 2019[EB/OL]. (2019-08-02)[2022-09-22]. https://www.health.govt.nz/system/files/documents/publications/guidelines-tuberculosis-control-new-zealand-2019-august2019-final.pdf.

|

| [35] |

National TB Elimination Programme. Guidelines for programmatic management of tuberculosis preventive treatment in India[EB/OL]. (2019-07-10)[2022-09-22]. https://tbcindia.gov.in/WriteReadData/l892s/Guidelines% 20for%20Programmatic%20Management%20of%20Tuberculosis%20Preventive%20Treatment%20in%20India.pdf.

|

| [36] |

Prevention Committee of the Japanese Society for Tuberculosis, Treatment Committee of the Japanese Society for Tuberculosis. Treatment guidelines for latent tuberculosis infection[J]. Kekkaku, 2014, 89(1): 21-37. |

| [37] |

Queensland Haelth. Management of contacts of multidrugresistant tuberculosis[EB/OL]. (2017-04-12)[2022-09-22]. https://www.health.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0023/444614/mdr-tuberculosis-contacts.pdf.

|

| [38] |

WHO. Global tuberculosis report 2022[EB/OL]. (2022-11-01)[2022-11-03]. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240061729.

|

| [39] |

Zhao YL, Xu SF, Wang LX, et al. National survey of drug-resistant tuberculosis in China[J]. N Engl J Med, 2012, 366(23): 2161-2170. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa1108789 |

| [40] |

Balcells ME, Thomas SL, Godfrey-Faussett P, et al. Isoniazid preventive therapy and risk for resistant tuberculosis[J]. Emerg Infect Dis, 2006, 12(5): 744-751. DOI:10.3201/eid1205.050681 |

| [41] |

van Halsema CL, Fielding KL, Chihota VN, et al. Tuberculosis outcomes and drug susceptibility in individuals exposed to isoniazid preventive therapy in a high HIV prevalence setting[J]. AIDS, 2010, 24(7): 1051-1055. DOI:10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833849df |

| [42] |

den Boon S, Matteelli A, Getahun H. Rifampicin resistance after treatment for latent tuberculous infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis, 2016, 20(8): 1065-1071. DOI:10.5588/ijtld.15.0908 |

| [43] |

Denholm JT, Leslie DE, Jenkin GA, et al. Long-term follow-up of contacts exposed to multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in Victoria, Australia, 1995-2010[J]. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis, 2012, 16(10): 1320-1325. DOI:10.5588/ijtld.12.0092 |

| [44] |

Bamrah S, Brostrom R, Dorina F, et al. Treatment for LTBI in contacts of MDR-TB patients, Federated States of Micronesia, 2009-2012[J]. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis, 2014, 18(8): 912-918. DOI:10.5588/ijtld.13.0028 |

| [45] |

Adler-Shohet FC, Low J, Carson M, et al. Management of latent tuberculosis infection in child contacts of multidrug- resistant tuberculosis[J]. Pediatr Infect Dis J, 2014, 33(6): 664-666. DOI:10.1097/INF.0000000000000260 |

| [46] |

Garcia-Prats AJ, Zimri K, Mramba Z, et al. Children exposed to multidrug-resistant tuberculosis at a home-based day care centre: a contact investigation[J]. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis, 2014, 18(11): 1292-1298. DOI:10.5588/ijtld.13.0872 |

| [47] |

Wu XG, Pang Y, Song YH, et al. Implications of a school outbreak of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in Northern China[J]. Epidemiol Infect, 2018, 146(5): 584-588. DOI:10.1017/S0950268817003120 |

| [48] |

Dayal R, Agarwal D, Bhatia R, et al. Tuberculosis burden among household pediatric contacts of adult tuberculosis patients[J]. Indian J Pediatr, 2018, 85(10): 867-871. DOI:10.1007/s12098-018-2661-9 |

| [49] |

Huang CC, Becerra MC, Calderon R, et al. Isoniazid preventive therapy in contacts of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis[J]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2020, 202(8): 1159-1168. DOI:10.1164/rccm.201908-1576OC |

| [50] |

Chang V, Ling RH, Velen K, et al. Latent tuberculosis infection among contacts of patients with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in New South Wales, Australia[J]. ERJ Open Res, 2021, 7(3): 00149-2021. DOI:10.1183/23120541.00149-2021 |

2023, Vol. 44

2023, Vol. 44