文章信息

- 伊娜, 刘婷婷, 周宇畅, 齐金蕾, 申昆玲, 周脉耕.

- Yi Na, Liu Tingting, Zhou Yuchang, Qi Jinlei, Shen Kunling, Zhou Maigeng

- 1990-2019年中国儿童青少年哮喘疾病负担分析

- Disease burden of asthma among children and adolescents in China, 1990-2019

- 中华流行病学杂志, 2023, 44(2): 235-242

- Chinese Journal of Epidemiology, 2023, 44(2): 235-242

- http://dx.doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn112338-20220526-00469

-

文章历史

收稿日期: 2022-05-26

2. 中国医科大学公共卫生学院, 沈阳 110122;

3. 国家儿童医学中心/首都医科大学附属北京儿童医院呼吸科/国家呼吸系统疾病临床医学研究中心, 北京 100045

2. School of Public Health, China Medical University, Shenyang 110122, China;

3. National Clinical Research Center of Respiratory Diseases, Respiratory Department, Beijing Children's Hospital, Capital Medical University, National Center for Children's Health, Beijing 100045, China

哮喘是儿童期常见的慢性呼吸道疾病之一[1],全球有1亿左右的儿童哮喘患者[2]。我国3次全国儿童哮喘流行病学调查结果显示,2010年儿童哮喘患病率较2000年和1990年均有显著上升[3]。2008-2018年中国0~19岁人群哮喘死亡率波动于0.023/10万~0.046/10万之间,尽管我国的哮喘死亡率在全球范围内处于较低水平,但由于我国人口基数较大,死亡人数仍然较高[4]。儿童期哮喘引起的肺功能损害还影响成年后的肺功能水平,导致沉重的疾病负担[5-6]。为描述1990-2019年我国1~19岁儿童青少年哮喘疾病负担的分布规律,本研究利用全球疾病负担(GBD)2019中国分省数据,分析中国儿童青少年哮喘的流行情况和疾病负担,为优化哮喘的公共卫生干预策略提供参考依据。

资料与方法1. 资料来源:来源于GBD2019中国分省数据。GBD2019分析了全球204个国家和地区的369种疾病或伤害导致的疾病负担和导致这些疾病的87种危险因素[7]。GBD2019中国儿童青少年哮喘发病和患病数据来源于对已发表的文献、未发表的报告、调查和医疗卫生服务系统数据等(不包含中国台湾地区)的系统回顾;死亡数据主要来源于全国疾病监测点系统死因监测、中国CDC死因登记报告信息系统、中国香港地区和中国澳门地区死因登记数据等,其中,全国死因监测系统覆盖全国605个监测点,总监测人口约占全国的24%[8]。人口数据来源于国家统计局,其他数据来源及分析方法见文献[7, 9]。

2. 疾病分类与编码:采用《国际疾病分类》第9版(ICD-9)和第10版(ICD-10)对死因数据进行编码。本研究中哮喘的ICD-9编码为493;ICD-10编码为J45~J46。由于对1岁以下婴儿进行哮喘的诊断困难,GBD2019未分析婴儿期的哮喘疾病负担,故本研究中儿童青少年指1~19岁人群[10]。

3. 数据分析和指标定义:GBD研究采用标准化方法对儿童青少年哮喘的发病、患病、死亡和疾病负担相关指标进行估计[7, 9]。本研究对现场调查和医保数据进行偏倚校正后,利用贝叶斯荟萃回归工具DisMod-MR 2.1估计不同省份、年份、年龄别和性别的哮喘发病率和患病率,使用医疗支出调查的数据估计患者中未控制、部分控制、控制和无症状哮喘所占的比例,再根据不同亚组的人口数计算各亚组的哮喘病例数和不同严重程度的哮喘病例数,由各组患病例数乘以不同严重程度哮喘对应的伤残权重获得伤残损失寿命年(years lived with disability,YLD)[11-12]。对死因数据垃圾编码进行再分配后,利用死因集成模型(cause of death ensemble model,CODEm)估计不同省份、年份、年龄别和性别的哮喘死亡率,并用死亡率乘以该亚组的人口数估算死亡人数;用死亡率除以发病率估算哮喘死亡发病比,并用死亡发病比估算发病人数;由各年龄别死亡人数乘以GBD标准寿命表中该年龄组的期望寿命算出过早死亡损失寿命年(years of life lost,YLL)[7, 13]。伤残调整寿命年(disability adjusted life year,DALY)为YLL与YLD之和。以GBD2019世界标准人口计算年龄标化率。本研究中,若未特别指明,疾病负担均指年龄标化DALY率。

4. 统计学分析:采用Excel软件进行数据整理和分析,比较了1990年和2019年我国儿童青少年分性别、年龄组的哮喘发病、患病、死亡的绝对数和率;估计了不同性别的儿童青少年哮喘的疾病负担分布;并利用地理绘图展示了1990-2019年疾病负担变化的空间差异,及2019年各省份儿童青少年哮喘疾病负担的空间分布。

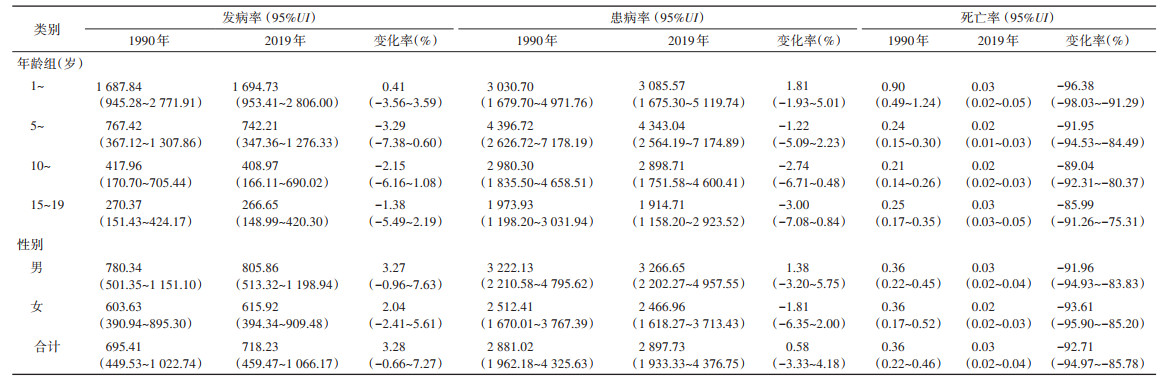

结果1. 1990年及2019年儿童青少年哮喘发病、患病和死亡情况:

(1) 发病情况:2019年我国儿童青少年哮喘发病人数为215.41万[95%不确定区间(UI):137.80万~319.76万],其中男性发病人数[130.19万(95%UI:82.93万~193.70万)]约为女性发病人数[85.22万(95%UI:54.56万~125.83万)]的2倍。不同年龄组中,1~4岁组人群哮喘发病人数最多[112.57万(95%UI:63.33万~186.38万)],15~19岁组人群哮喘发病人数最少[20.03万(95%UI:11.19万~31.58万)]。见表 1。

2019年儿童青少年哮喘发病率为718.23/10万(95%UI:459.47/10万~1 066.17/10万),男性发病率[805.86/10万(95%UI:513.32/10万~1 198.94/10万)]高于女性[615.92/10万(95%UI:394.34/10万~909.48/10万)]。不同年龄组中,1~4岁组发病率最高[1 694.73/10万(95%UI:953.41/10万~2 806.00/10万)],15~19岁组发病率最低[266.65/10万(95%UI:148.99/10万~420.30/10万)]。

2019年儿童青少年哮喘发病率高于1990年[变化率为3.28%(95%UI:-0.66%~7.27%)],其中男性变化率为3.27%(95%UI:-0.96%~7.63%),略高于女性[2.04%(95%UI:-2.41%~5.61%)]。但在不同年龄组中,仅1~4岁组人群发病率上升[变化率为0.41%(95%UI:-3.56%~3.59%)],除此之外,5~、10~和15~19岁组的发病率均出现下降,变化率分别为-3.29%(95%UI:-7.38%~0.60%)、-2.15%(95%UI:-6.16%~1.08%)和-1.38%(95%UI:-5.49%~ 2.19%)。见表 2。

(2) 患病情况:2019年我国儿童青少年哮喘总患病人数为869.07万(95%UI:579.83万~1 312.65万),远少于1990年的患病人数[1 295.86万(95%UI:882.57万~1 945.64万)]。男性患病人数[527.75万(95%UI:355.79万~800.92万)]多于女性[341.32万(95%UI:223.90万~513.79万)]。其中,5~9岁组人群哮喘患病人数最多[315.45万(95%UI:186.24万~521.13万)],15~19岁组人群哮喘患病人数最少[143.86万(95%UI:87.02万~219.66万)]。见表 1。

2019年儿童青少年哮喘患病率为2 897.73/10万(95%UI:1 933.33/10万~4 376.75/10万),男性的患病率[3 266.65/10万(95%UI:2 202.27/10万~4 957.55/10万)]高于女性[2 466.96/10万(95%UI:1 618.27/10万~3 713.43/10万)]。其中,5~9岁组的患病率最高[4 343.04/10万(95%UI:2 564.19/10万~ 7 174.89/10万)],15~19岁组的患病率最低[1 914.71/10万(95%UI:1 158.20/10万~2 923.52/10万)]。

2019年儿童青少年哮喘患病率高于1990年[变化率为0.58%(95%UI:-3.33%~4.18%)],其中,男性变化率为1.38%(95%UI:-3.20%~5.75%),女性变化率为-1.81%(95%UI:-6.35%~2.00%)。不同年龄组中,仅1~4岁组的患病率出现了上升[变化率为1.81%(95%UI:-1.93%~5.01%)]。见表 2。

(3) 死亡情况:2019年我国儿童青少年哮喘死亡总数为78(95%UI:63~106),远低于1990年死亡人数[1 613(95%UI:993~2 057)]。男性死亡人数[47(95%UI:34~67)]略多于女性[32(95%UI:25~43)]。其中,5~9岁组人群哮喘死亡人数[14(95%UI:11~20)]最少,15~19岁组人群哮喘死亡人数[26(95%UI:20~35)]最多。见表 1。

2019年儿童青少年哮喘死亡率为0.03/10万(95%UI:0.02/10万~0.04/10万),男性[0.03/10万(95%UI:0.02/10万~0.04/10万)]与女性[0.02/10万(95%UI:0.02/10万~0.03/10万)]的死亡率相近。各年龄组死亡率均在0.02/10万~0.03/10万之间。

2019年儿童青少年哮喘的死亡率低于1990年[变化率为-92.17%(95%UI:-94.97%~-85.78%)]。女性变化率[-93.61%(95%UI:-95.90%~-85.20%)]略高于男性[-91.96%(95%UI:-94.93%~-83.83%)]。各年龄组中,1~4岁组人群哮喘死亡率降幅最大[变化率为-96.38%(95%UI:-98.03%~-91.29%)]。见表 2。

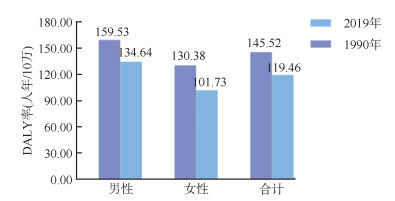

2. 1990年及2019年儿童青少年哮喘疾病负担:与1990年相比,2019年我国儿童青少年哮喘的年龄标化DALY率下降了17.91%(26.06人年/10万)。其中,男性下降了24.89人年/10万,女性下降了28.65人年/10万。女性的降幅(-21.97%)大于男性(-15.60%)。见图 1。

|

| 注:变化率:男性:-15.60%,女性:-21.97%,合计:-17.91% 图 1 1990年及2019年中国儿童青少年哮喘年龄标化伤残调整寿命年(DALY)率 |

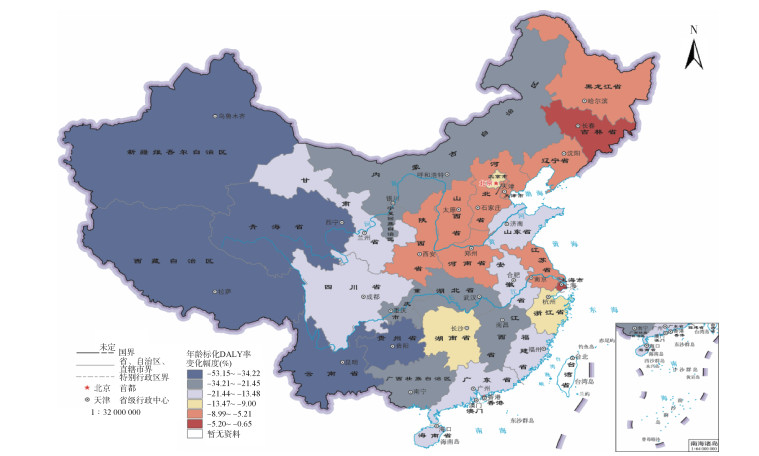

1990-2019年我国各省份儿童青少年哮喘年龄标化DALY率变化幅度见图 2。整体上看,儿童青少年哮喘疾病负担的降幅呈现东部地区小、西部地区大的趋势。降幅最大的3个省份为云南省(-53.15%)、贵州省(-45.46%)和西藏自治区(-35.61%);上海市(-0.28%)、吉林省(-1.60%)、澳门特别行政区(-1.93%)、江苏省(-5.21%)和黑龙江省(-5.26%)等在降低儿童青少年哮喘疾病负担方面的成效较小。值得注意的是,香港特别行政区是唯一出现了疾病负担增加(0.65%)的地区。

|

| 注:审图号:GS(2022)3201号;DALY:伤残调整寿命年 图 2 1990-2019年中国儿童青少年哮喘年龄标化DALY率变化幅度 |

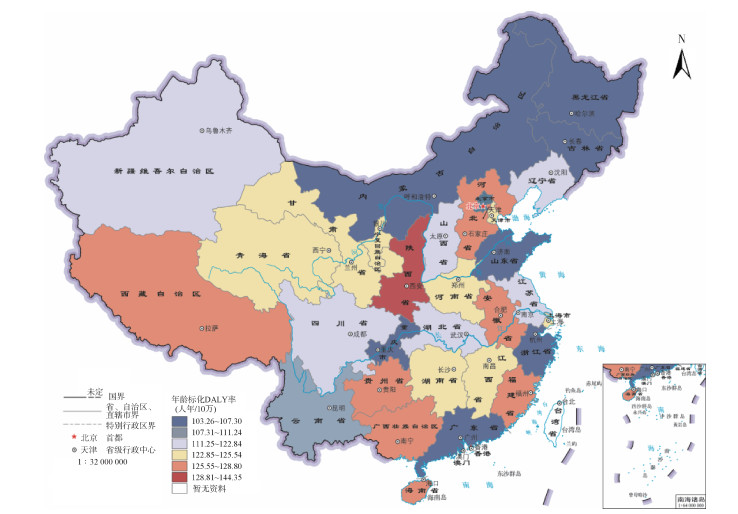

3. 2019年各省份儿童青少年哮喘疾病负担分布:2019年我国各省份儿童青少年哮喘年龄标化DALY率在103.26人年/10万~144.35人年/10万之间。男性(134.64人年/10万)的疾病负担大于女性(101.73人年/10万)。见图 1。香港特别行政区儿童青少年哮喘疾病负担最高(144.35人年/10万),其次为陕西省(138.67人年/10万)、福建省(128.8人年/10万)、海南省(128.1人年/10万)和广西壮族自治区(127.21人年/10万)等;黑龙江省疾病负担最低(103.26人年/10万),其次为浙江省(104.37人年/10万)、北京市(105.01人年/10万)、内蒙古自治区(105.18人年/10万)和广东省(105.86人年/10万)等。见图 3。

|

| 注:审图号:GS(2022)3201号;DALY:伤残调整寿命年 图 3 2019年中国儿童青少年哮喘年龄标化DALY率 |

本研究利用GBD2019中国分省数据对儿童青少年哮喘的疾病负担进行分析,结果显示,1990-2019年儿童青少年哮喘的发病人数、患病人数、死亡人数和死亡率呈现下降趋势,然而,哮喘的发病率、患病率呈现上升趋势。与1990年相比,2019年我国除香港特别行政区外的省份儿童青少年哮喘的年龄标化DALY率均出现下降,但年龄标化DALY率的降幅仍呈现东部地区小、西部地区大的形势且男性儿童青少年哮喘的疾病负担大于女性。

本研究结果发现,2019年我国儿童青少年哮喘发病率高于1990年。2019年15~19岁组的发病率是1~19岁人群中发病率最低的年龄组,1~4岁组儿童的发病率约为15~19岁组的6倍,这与我国儿童哮喘流行病学调查发现的儿童哮喘发病年龄特点一致[14]。有研究认为儿童哮喘的发病率与早期接触PM2.5、PM10、SO2和NO2等空气污染物有关[15-16],随着空气质量的改善,15岁以上人群患哮喘的风险降低。此外,婴儿期抗生素的使用、益生菌的补充、饲养宠物以及肥胖等因素也会影响儿童哮喘的发病率[17-19]。

近年来,全球各国儿童青少年哮喘的患病率总体仍在上升[20],本研究也显示相同的结果。导致儿童青少年哮喘患病率上升的因素是多方面的。有研究认为儿童青少年哮喘的患病率增加可能与母乳喂养时间短、不良童年经历、围产期的家庭环境、早产、春秋季节出生、无指征剖腹产和扑热息痛的使用等因素有关[21-22]。本研究结果显示,2019年5~9岁组的患病率最高,15~19岁组的患病率最低。有研究认为5~9岁年龄组的儿童免疫系统较弱,自我管理能力较差,因此容易受到上呼吸道感染的影响。随着年龄的增长,儿童自我管理能力和免疫力增强,哮喘的患病率因此下降[23-25]。

相比1990年,2019年我国儿童青少年哮喘死亡人数和死亡率均出现大幅下降,这与全球儿童青少年哮喘死亡率的下降趋势相同[13]。过去的25年中,全球儿童青少年哮喘死亡率的下降,很大程度上归因于吸入糖皮质激素的使用增加[26]。中国儿童青少年哮喘的死亡率低于其他国家公布的数据[27]。我国儿童青少年哮喘死亡率的下降,也可能与吸入型糖皮质激素使用的普及和儿童哮喘管理水平的提高有关[14]。尽管我国儿童青少年哮喘的死亡率较低,但由于我国人口基数大,死亡人数仍处于较高水平[4]。因此,减少哮喘相关的死亡也是哮喘管理的长期目标之一[4]。此外,本研究结果显示儿童青少年哮喘死亡率下降的同时发病率和患病率呈上升趋势,这提醒卫生健康工作者仍需要持续关注哮喘所致的非死亡相关的疾病负担。

随着全球哮喘防治协议的推广,儿童哮喘的管理水平有所提高。既往研究显示,1990-2019年,全球范围内儿童青少年哮喘的疾病负担下降[13]。我国儿童青少年哮喘的年龄标化DALY率整体上也呈下降趋势,2019年我国儿童青少年哮喘疾病负担处于全球较低水平[13]。反映出随着我国医疗服务体系的建设和不断完善,哮喘的诊疗水平提高,哮喘患者得到了有效救治[3, 14]。我国儿童青少年哮喘疾病负担的降幅呈现东部地区小、西部地区大的趋势。究其原因,可能是由于我国西部地区经济条件和生活水平的提高,医疗资源的改善,居民的身体素质提高,哮喘的疾病负担大幅下降。但2019年我国部分西部地区哮喘的疾病负担仍大于东部地区,可见,我国仍需要不断优化医疗资源配置,提高儿童青少年哮喘的防治水平。

此外,本研究发现儿童青少年哮喘的疾病负担存在性别差异,男性高于女性。我国第三次中国城市儿童哮喘流行病学调查结果显示男性患病率显著高于女性[14]。这与2003-2015年美国一项19岁以下人群哮喘死亡率调查的结果一致[28]。日本的一项5~34岁人群哮喘死亡率的研究中也观察到类似的结果[29]。这种性别差异可能与性激素水平、气道口径、遗传以及诊断的差异等因素有关[26, 30-33]。在成年人中,女性哮喘的疾病负担高于男性,这表明哮喘的患病机制在青春期发生了转变[33]。这可能是由于与青春期前的女性相比,男性气道大小与肺体积比例较小,而这种情况会在青春期发生转变[26]。哮喘疾病负担的性别差异,提示需要进一步深入研究其机制,以便制定更具针对性的哮喘治疗方案。

本研究存在局限性。首先,本研究基于GBD2019的数据和方法进行估计,GBD对哮喘疾病负担估计方法的局限性在本研究中也同样存在,结果与真实水平存在一定差异[9]。其次,本研究所使用的数据无法从城乡角度分析儿童青少年哮喘疾病负担的差异,既往研究显示农村地区儿童哮喘的死亡率高于城市儿童[34-35]。再者,GBD2019数据未提供归因于空气污染物、花粉、呼吸道感染、烟草烟雾暴露和季节变化等因素的儿童青少年哮喘疾病负担,无法将这些危险因素纳入分析。

综上所述,1990-2019年,我国儿童青少年哮喘的发病率和患病率上升,死亡率下降;疾病负担下降,但降幅仍存在地区差异且男性的疾病负担大于女性。因此,哮喘对我国儿童青少年造成的非死亡相关的疾病负担仍不容忽视,国家应进一步优化医疗资源配置,在哮喘防治中注重性别特点,加强儿童青少年哮喘的早期预防与干预。

利益冲突 所有作者声明无利益冲突

作者贡献声明 伊娜:数据整理、论文撰写;刘婷婷、周宇畅:论文修改;齐金蕾、申昆玲:研究指导、论文修改;周脉耕:研究指导、论文修改、经费支持

| [1] |

Masoli M, Fabian D, Holt S, et al. The global burden of asthma: executive summary of the GINA Dissemination Committee report[J]. Allergy, 2004, 59(5): 469-478. DOI:10.1111/j.1398-9995.2004.00526.x |

| [2] |

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, The GBD results tool[EB/OL]. [2022-05-10]. |

| [3] |

全国儿童哮喘防治协作组. 中国城区儿童哮喘患病率调查[J]. 中华儿科杂志, 2003, 41(2): 47-51. National Cooperation Group on Childhood Asthma. A nationwide survey in China on prevalence of asthma in urban children[J]. Chin J Pediatr, 2003, 41(2): 47-51. DOI:10.3760/j.issn:0578-1310.2003.02.014 |

| [4] |

刘婷婷, 齐金蕾, 殷菊, 等. 2008年至2018年中国0~19岁人群哮喘死亡现状及变化趋势分析[J]. 中华实用儿科临床杂志, 2021, 36(6): 471-475. Liu TT, Qi JL, Yin J, et al. Analysis of death status and change trend of asthma among Chinese people aged 0-19 years from 2008 to 2018[J]. Chin J Appl Clin Pediatr, 2021, 36(6): 471-475. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.cn101070-20201128-01821 |

| [5] |

Wu P, Xu BP, Shen AD, et al. The economic burden of medical treatment of children with asthma in China[J]. BMC Pediatr, 2020, 20(1): 386. DOI:10.1186/s12887-020-02268-6 |

| [6] |

Tai A, Tran H, Roberts M, et al. The association between childhood asthma and adult chronic obstructive pulmonary disease[J]. Thorax, 2014, 69(9): 805-810. DOI:10.1136/thoraxjnl-2013-204815 |

| [7] |

GBD 2019 Risk Factors Collaborators. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019[J]. Lancet, 2020, 396(10258): 1223-1249. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30752-2 |

| [8] |

Liu SW, Wu XL, Lopez AD, et al. An integrated national mortality surveillance system for death registration and mortality surveillance, China[J]. Bull World Health Organ, 2016, 94(1): 46-57. DOI:10.2471/BLT.15.153148 |

| [9] |

GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019[J]. Lancet, 2020, 396(10258): 1204-1222. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9 |

| [10] |

World Health Organization. Orientation programme on adolescent health for health-care providers[M]. Geneva: WHO, 2006.

|

| [11] |

Salomon JA, Haagsma JA, Davis A, et al. Disability weights for the Global Burden of Disease 2013 study[J]. Lancet Glob Health, 2015, 3(11): e712-723. DOI:10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00069-8 |

| [12] |

GBD 2015 Chronic Respiratory Disease Collaborators. Global, regional, and national deaths, prevalence, disability-adjusted life years, and years lived with disability for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015[J]. Lancet Respir Med, 2017, 5(9): 691-706. DOI:10.1016/S2213-2600(17)30293-X |

| [13] |

Zhang DQ, Zheng JX. The burden of childhood asthma by age group, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis of global burden of disease 2019 data[J]. Front Pediatr, 2022, 10: 823399. DOI:10.3389/fped.2022.823399 |

| [14] |

全国儿科哮喘协作组, 中国疾病预防控制中心环境与健康相关产品安全所. 第三次中国城市儿童哮喘流行病学调查[J]. 中华儿科杂志, 2013, 51(10): 729-735. The National Cooperative Group on Childhood Asthma, Institute of Environmental Health and Related Product Safety, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Third nationwide survey of childhood asthma in urban areas of China[J]. Chin J Pediatr, 2013, 51(10): 729-735. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0578-1310.2013.10.003 |

| [15] |

Buteau S, Doucet M, Tétreault LF, et al. A population-based birth cohort study of the association between childhood-onset asthma and exposure to industrial air pollutant emissions[J]. Environ Int, 2018, 121(Pt 1): 23-30. DOI: 10.1016/j.envint.2018.08.040.

|

| [16] |

To T, Zhu JQ, Stieb D, et al. Early life exposure to air pollution and incidence of childhood asthma, allergic rhinitis and eczema[J]. Eur Respir J, 2020, 55(2): 1900913. DOI:10.1183/13993003.00913-2019 |

| [17] |

Lang JE. Obesity and childhood asthma[J]. Curr Opin Pulm Med, 2019, 25(1): 34-43. DOI:10.1097/MCP.0000000000000537 |

| [18] |

Patrick DM, Sbihi H, Dai DLY, et al. Decreasing antibiotic use, the gut microbiota, and asthma incidence in children: evidence from population-based and prospective cohort studies[J]. Lancet Respir Med, 2020, 8(11): 1094-1105. DOI:10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30052-7 |

| [19] |

Wei XC, Jiang P, Liu JB, et al. Association between probiotic supplementation and asthma incidence in infants: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials[J]. J Asthma, 2020, 57(2): 167-178. DOI:10.1080/02770903.2018.1561893 |

| [20] |

Asher MI, García-Marcos L, Pearce NE, et al. Trends in worldwide asthma prevalence[J]. Eur Respir J, 2020, 56(6): 2002094. DOI:10.1183/13993003.02094-2020 |

| [21] |

Ellie AS, Sun YX, Hou J, et al. Prevalence of childhood asthma and allergies and their associations with perinatal exposure to home environmental factors: a cross-sectional study in Tianjin, China[J]. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2021, 18(8): 4131. DOI:10.3390/ijerph18084131 |

| [22] |

Hu YB, Chen YT, Liu SJ, et al. Increasing prevalence and influencing factors of childhood asthma: a cross-sectional study in Shanghai, China[J]. World J Pediatr, 2021, 17(4): 419-428. DOI:10.1007/s12519-021-00436-x |

| [23] |

Guo XJ, Li ZY, Ling WJ, et al. Epidemiology of childhood asthma in mainland China (1988-2014): a meta-analysis[J]. Allergy Asthma Proc, 2018, 39(3): 15-29. DOI:10.2500/aap.2018.39.4131 |

| [24] |

Martinez FD. Respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis and the pathogenesis of childhood asthma[J]. Pediatr Infect Dis J, 2003, 22(2 Suppl): S76-82. DOI:10.1097/01.inf.0000053889.39392.a7 |

| [25] |

Li X, Song PG, Zhu YJ, et al. The disease burden of childhood asthma in China: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. J Glob Health, 2020, 10(1): 010801. DOI:10.7189/jogh.10.01081 |

| [26] |

Papi A, Brightling C, Pedersen SE, et al. Asthma[J]. Lancet, 2018, 391(10122): 783-800. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)33311-1 |

| [27] |

Ebmeier S, Thayabaran D, Braithwaite I, et al. Trends in international asthma mortality: analysis of data from the WHO Mortality Database from 46 countries (1993-2012)[J]. Lancet, 2017, 390(10098): 935-945. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31448-4 |

| [28] |

Arroyo AJC, Chee CP, Camargo CA, et al. Where do children die from asthma? National data from 2003 to 2015[J]. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract, 2018, 6(3): 1034-1036. DOI:10.1016/j.jaip.2017.08.032 |

| [29] |

Ito Y, Tamakoshi A, Wakai K, et al. Trends in asthma mortality in Japan[J]. J Asthma, 2002, 39(7): 633-639. DOI:10.1081/jas-120014928 |

| [30] |

Shah R, Newcomb DC. Sex bias in asthma prevalence and pathogenesis[J]. Front Immunol, 2018, 9: 2997. DOI:10.3389/fimmu.2018.02997 |

| [31] |

Arathimos R, Granell R, Haycock P, et al. Genetic and observational evidence supports a causal role of sex hormones on the development of asthma[J]. Thorax, 2019, 74(7): 633-642. DOI:10.1136/thoraxjnl-2018-212207 |

| [32] |

Yung JA, Fuseini H, Newcomb DC. Hormones, sex, and asthma[J]. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol, 2018, 120(5): 488-494. DOI:10.1016/j.anai.2018.01.016 |

| [33] |

Leynaert B, Sunyer J, Garcia-Esteban R, et al. Gender differences in prevalence, diagnosis and incidence of allergic and non-allergic asthma: a population-based cohort[J]. Thorax, 2012, 67(7): 625-631. DOI:10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-201249 |

| [34] |

Lawson JA, Rennie DC, Cockcroft DW, et al. Childhood asthma, asthma severity indicators, and related conditions along an urban-rural gradient: a cross-sectional study[J]. BMC Pulm Med, 2017, 17(1): 4. DOI:10.1186/s12890-016-0355-5 |

| [35] |

Hernández-Garduño E. Asthma mortality among Mexican children: rural and urban comparison and trends, 1999-2016[J]. Pediatr Pulmonol, 2020, 55(4): 874-881. DOI:10.1002/ppul.24658 |

2023, Vol. 44

2023, Vol. 44