文章信息

- 杜文秀, 顾叶青, 孟革, 张卿, 刘莉, 武汉章, 牛凯军.

- Du Wenxiu, Gu Yeqing, Meng Ge, Zhang Qing, Liu Li, Wu Hanzhang, Niu Kaijun

- 网络成瘾和电子屏幕时间与抑郁症状的关联性研究

- Associations between internet addiction, screen time and depressive symptoms

- 中华流行病学杂志, 2022, 43(11): 1731-1738

- Chinese Journal of Epidemiology, 2022, 43(11): 1731-1738

- http://dx.doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn112338-20220330-00246

-

文章历史

收稿日期: 2022-03-30

2. 天津中医药大学公共卫生与健康科学学院, 天津 301617;

3. 中国医学科学院放射医学研究所营养与辐射流行病学研究中心, 天津 300192;

4. 天津医科大学总医院健康管理中心, 天津 300052

2. School of Public Health of Tianjin University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Tianjin 301617, China;

3. Nutrition and Radiation Epidemiology Research Center, Institute of Radiation Medicine, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College, Tianjin 300192, China;

4. Health Management Centre, Tianjin Medical University General Hospital, Tianjin 300052, China

精神障碍是全球疾病负担的主要原因,而抑郁症是普遍的精神障碍[1]。预计到2030年,抑郁症将成为全球第二疾病负担,并且是高收入国家的主要疾病负担[2]。1990-2017年我国抑郁症的发病率从3 224.6/10万增长至3 990.5/10万[3]。2017年,中国有5 636万抑郁症患者,占全球病例的21.3%,抑郁症已逐渐成为影响中国人口的重要公共卫生问题[3]。既往研究表明抑郁症与精神障碍的家族史、生活压力、躯体疾病、缺乏社会支持等有关[4],但这些因素通常是很难或无法改变的。也有研究表明抑郁症状与网络成瘾、电子屏幕时间密切关联[4-5]。互联网作为信息共享的重要工具,在过去50年显著增长,在过去10年里全球的增长率为305.5%[6]。适度使用互联网在工作学习中有益,过度使用于身心健康无益[7]。网络成瘾也被称为病理性互联网使用,指无法控制自己使用互联网的时间,导致明显的痛苦和/或功能障碍[8]。作为互联网的载体,电脑、手机、电视在不断更新,使人们工作学习更加便捷。但既往研究表明,长时间地使用电子屏幕(包括电视、电脑和手机)与心血管疾病[9]、糖尿病[10]有关,也会影响人们的精神健康,比如失眠和抑郁[5]。本研究旨在利用天津慢性低度炎症与健康(TCLSIH)队列的数据,探讨网络成瘾和电子屏幕时间与随访期间出现抑郁症状的关联。

资料与方法1. 资料来源:数据资料来源于天津医科大学营养流行病学研究所与天津医科大学总医学健康管理中心共同建立的TCLSIH队列研究数据库[11-12]。TCLSIH队列是一项前瞻性动态队列,旨在调查天津市人群慢性低度炎症与各种健康指标之间的关系。研究对象来自于2013-2019年TCLSIH队列,包含了各种职业的在职人员和退休人员,共计13 673人。纳入标准:①2013-2019年进入队列的参与者;② < 60岁的成年人;③接受体格检查并愿意完成问卷填写者;④自愿参加研究且签署知情同意书,并允许其数据用于统计分析。排除不可信数据和缺失数据(3 596人),自报患有心脑血管疾病(499人)、患有恶性肿瘤(67人)、患有抑郁症状(1 677人)和在基线随访中没有健康体检(902人)的研究对象。最终6 932人纳入分析。其中男性3 949人,女性2 983人,年龄(38.32±8.71)岁。本研究取得天津医科大学机构审查委员会批准(审批文号:TMUhMEC201430)。

2. 研究方法:

(1)网络成瘾评估:通过自我报告问卷中的问题“你感觉自己有网络依赖,或对网络成瘾吗?”,评估是否有网络成瘾及严重程度。研究对象可以选择“无”“曾经是,现在不是”“轻度(没有影响到工作学习、生活和人际关系等)”“中度(工作学习、生活和人际关系已受到影响,但程度不很严重)”“重度(工作学习、生活和人际关系受到严重影响)”。

(2)电子屏幕时间评估:屏幕时间量表是WHO推荐的针对屏幕观看时间的调查表,用于统计过去一周研究对象电子屏幕使用时间。在本研究中,分别统计工作日和周末的电子屏幕时间,屏幕设备包括电视、电脑和手机。平均每日电子屏幕时间=(工作日电子屏幕时间×5+周末电子屏幕时间×2)÷7。

(3)抑郁症状评估:使用中文版抑郁自评量表(SDS)评估研究对象的抑郁症状。该量表共有20个条目评估研究对象过去一周的抑郁症状。每个条目为1~4分,总分为20~80分,越高的分数提示越严重的抑郁症状。以往的研究证明该问卷在中国成年人群中具有可靠性和有效性[13-14]。在本研究中,SDS总分≥45分被认定为有抑郁症状[15-16]。

(4)其他协变量:①社会人口学:包括研究对象的年龄、性别、职业(管理人员、专业技术人员、其他)、文化程度(小学、中学、高中、大学、研究生)、社会关系(婚姻状况、同居人员情况和子女情况)和每月家庭总收入(< 3 000、3 000~、5 000~、> 10 000元)。②体格检查:包括BMI、腰围、TC、TG、LDL-C、HDL-C、SBP、DBP。③生活方式问卷调查:包括吸烟状况(吸烟/戒烟/从不吸烟)、饮酒状况(每天/有时/戒酒/从不饮酒)、睡眠时间。通过问询研究对象过去一个月的入睡和起床时间,计算睡眠时间并将其分为3类:< 6.0、6.0~、> 7.5 h/d。采用国际体力活动问卷评估研究对象一周的身体活动[17]。该量表评估研究对象过去一周静坐、步行、中等强度体力活动(骑自行车、打太极、做家务等)和重体力活动(跑步、游泳、跳绳等)。按照系数换算成身体活动代谢当量(MET),总身体活动为3种强度体力活动之和[17]。通过询问研究对象每天(9:00~17:00)在户外的时间,计算出平均每日的户外时间并分为4类:< 1、1~、3~、> 5 h/d。④膳食调查:通过改良版的食物频率调查问卷(food frequency questionnaires,FFQ)评估研究对象的膳食情况,该问卷包含100种食物[18]。问卷中食物的摄入频率从“几乎不吃”到“每日≥2次”共7个等级;饮料的摄入频率从“几乎不喝”到“每日≥4杯”共8个等级。将得到的食物摄入频率与来源于中国食物成分表的基础数据库相结合,计算每位研究对象各类营养素及每日总能量的摄入量。本研究已对FFQ的信度和效度进行检验[19],可反映研究对象的长期饮食习惯。100种食物经过结合特征值判定、碎石图检验和有限元分析可解释性,确定了3个因子,并将膳食分为3类:因子1是以蔬菜为特征的植物性膳食模式;因子2是以肉类为特征的动物性膳食模式;因子3是以中式点心、饼干和各种水果为特征的甜膳食模式。

3. 统计学方法:数据分析采用SAS 9.3软件,双侧检验,以P < 0.05为差异有统计学意义。连续变量不符合正态分布使用M(Q1,Q3)表示,分类变量使用百分比(%)表示。将SDS总分45分为界点,分为无抑郁症状组和有抑郁症状组。采用t检验分析数值变量,比较无抑郁症状组和有抑郁症状组之间基线特征的差异,分类变量采用χ2检验进行分析。采用Cox比例风险回归模型评估网络成瘾、电脑/手机使用时间、电视使用时间与随访期间出现的抑郁症状之间的关联。模型1:粗模型;模型2:调整年龄、性别、BMI,其他变量不调整;模型3:在模型2基础上,调整腰围、血脂、血压、总能量摄入、甜膳食模式得分、植物性膳食模式得分、动物性膳食模式得分、每月家庭总收入、文化程度、职业、婚姻状况、身体活动量、吸烟状况、饮酒状况、户外活动时间、睡眠时间、独居、经常与朋友往来、个人疾病史(高血压、高脂血症、糖尿病)和家族疾病史(心血管疾病、高血压、高脂血症、糖尿病);模型4:包含模型3中所有变量,再加上对网络成瘾、电脑/手机使用时间、电视使用时间进行相互调整。

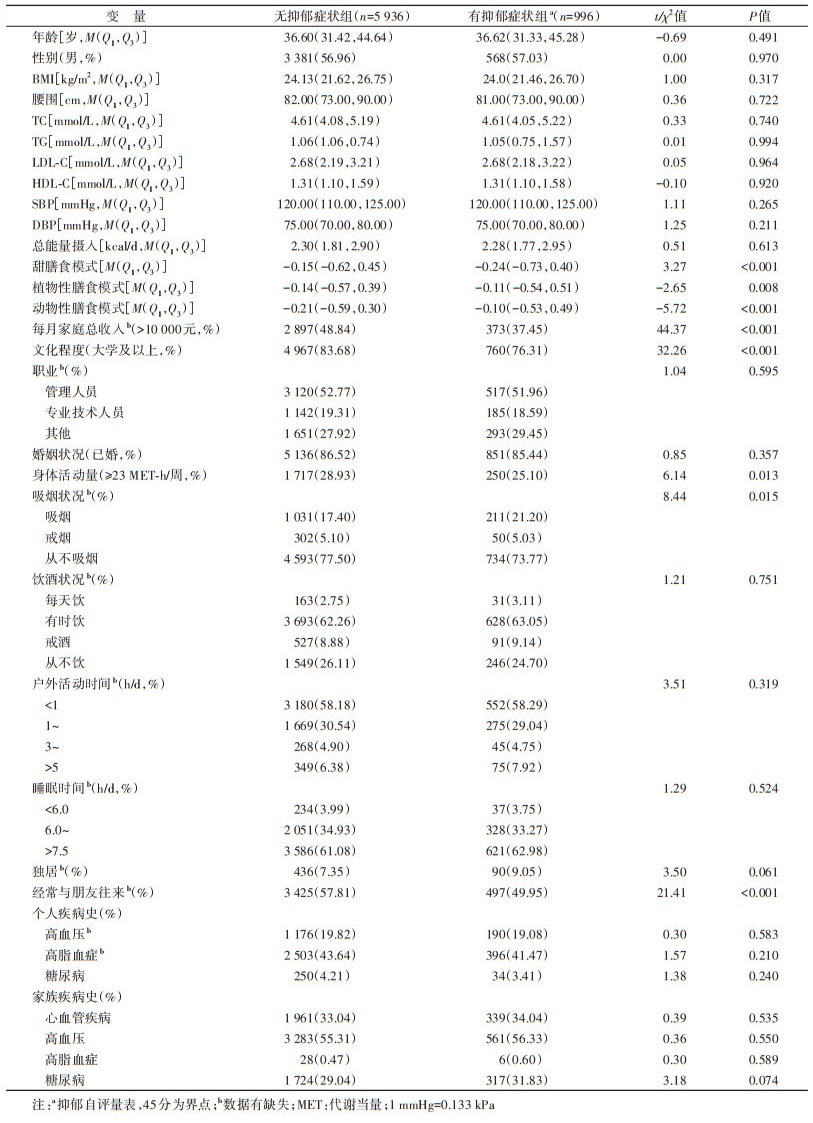

结果1. 基线特征:在6 932名研究对象中,SDS≥45分有996人(14.37%);与无抑郁症状组人群相比,有抑郁症状组人群倾向于少摄入植物性膳食模式(P < 0.05),而多摄入甜膳食模式(P < 0.001)和动物性膳食模式(P < 0.001);有抑郁症状组人群每月家庭总收入低(P < 0.001)、文化程度低(P < 0.001)、身体活动量少(P=0.013)、吸烟者的比例高(P=0.015)、经常与朋友往来的比例低(P < 0.001)。见表 1。

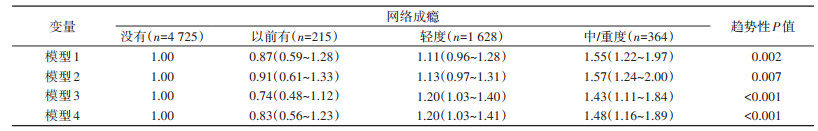

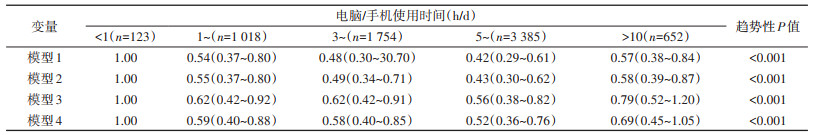

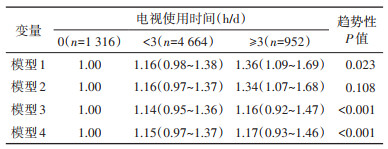

2. 关联分析:对于网络成瘾,控制潜在的混杂因素后,与无网络成瘾者相比,轻度网络成瘾者和中/重度网络成瘾者出现抑郁症状的HR值(95%CI)为1.20(1.03~1.41)和1.48(1.16~1.89)。网络成瘾与出现抑郁症状之间的线性关联有统计学意义(趋势性P < 0.001);对于以前有网络成瘾者,出现抑郁症状的HR值(95%CI)为0.83(0.56~1.23)。见表 2。对于电脑/手机使用时间,调整潜在混杂因素后,与使用 < 1 h/d相比,使用电脑/手机1~、3~、5~和 > 10 h/d出现抑郁症状的HR值(95%CI)分别为0.59(0.40~0.88)、0.58(0.40~0.85)、0.52(0.36~0.76)和0.69(0.45~ 1.05)。使用1~10 h/d时,电脑/手机使用时间与降低随访期间抑郁症状有关。但当使用 > 10 h/d时,电脑/手机使用时间与降低随访期间抑郁症状无关联。即电脑/手机使用时间与随访期间出现抑郁症状之间的关联存在“U”形趋势(趋势性P < 0.001)。见表 3。对于电视使用时间,未调整和初步调整潜在混杂因素后,与每天不使用电视相比,电视使用时间≥3 h/d出现抑郁症状的HR值(95%CI)为1.36(1.09~1.69)和1.34(1.07~1.68)。电视使用时间≥3 h/d与随访期间抑郁症状风险增加有关。然而调整所有潜在混杂因素后,电视使用时间与随访期间出现抑郁症状之间没有关联(趋势性P < 0.001)。见表 4。

抑郁症的具体病理机制尚不明确,与社会环境、基因、生物学密切相关,是多因素疾病[20-22]。目前抑郁症在生物机制方面的假说有单胺类神经递质假说、非单胺类神经递质假说、神经内分泌系统假说[23-26]。但鉴于抑郁症的高发病率和未治疗的严重后果,采取多种方法来预防或延缓抑郁症非常必要[27]。

在本研究中利用TCLSIH队列平均6年的随访数据,探究网络成瘾和电子屏幕时间与随访期间出现抑郁症状的关联。结果显示,未调整和初步调整混杂因素电视使用时间≥3 h/d与抑郁症状风险增加有关。调整潜在混杂因素后,网络成瘾越严重随访期间出现抑郁症状的风险越高。而电脑/手机使用时间与降低随访期间出现抑郁症状的风险有关。

本研究参考既往文献[5, 28],将年龄、性别、BMI纳入模型2中调整后发现,中/重度网络成瘾与抑郁症状相关。比较有抑郁症状组和无症状组的基线特征时发现两组在饮食模式、文化程度、身体活动量等变量存在差异,在模型3中对组间差异变量进行调整。考虑到3种常见的慢性病(高血压、高脂血症和糖尿病)影响网络成瘾、屏幕时间与抑郁症状的关系[29],结合血液标本检测结果来识别疾病状态,并将慢性病纳入模型3进行调整。结合社会人口因素、生活方式因素和家族疾病史会影响网络成瘾和屏幕时间与抑郁症状之间的关联[30-32],对相关变量进行了调整。最后考虑到网络成瘾、电脑/手机使用时间、电视使用时间三者之间相互影响,最终会影响到网络成瘾、屏幕时间与抑郁症状的关联[33-34],将三者纳入模型4进行调整,网络成瘾和电子屏幕时间与抑郁症状的关联被发现。

随社会发展和电子屏幕产品功能不断增强,人们对电子屏幕产品尤其是“新”媒体的行为上瘾是一个日益严重的社会问题,既往的研究大多局限在青少年,成年人网络成瘾情况几乎被忽视。本研究中报告中/重度网络成瘾的参与者出现抑郁症状的风险显著增加,这与之前的横断面研究结果基本一致[35-37]。可能的机制:第一,网络成瘾与睡眠障碍存在关联,而睡眠障碍与抑郁症状密切相关。一项针对网络成瘾与睡眠障碍的系统综述表明网络成瘾和睡眠问题之间存在显著的关系,有网络成瘾的人有睡眠问题的概率是没有网络成瘾的人的2.2倍。本研究表明,有网络成瘾的人睡眠时长更短,质量更差,其可能无法从睡眠中得到有效的休息,继而出现健康问题,例如情绪困扰及疲劳[38]。而睡眠障碍是抑郁症的常见特征[39]。尼泊尔的一项研究显示,网络成瘾介导睡眠质量对抑郁症状16.5%的间接影响,而睡眠质量独立介导网络成瘾对抑郁症状30.9%的间接影响[37]。第二,网络成瘾者会因为孤独和社会孤立而引起抑郁症状[40],其往往会忽视工作和社会交往造成社会孤立[41]。工作对即使是患有精神疾病的人也可以在改善生活质量和社区融合方面发挥重要作用[42]。

本研究结果显示,电脑/手机使用时间与降低随访期间出现抑郁症状的风险有关。当电脑/手机使用时间为1~10 h/d时,相关性最高,且有统计学意义。可能与以下两方面有关:第一,在职人员使用电子屏幕与工作相关。本研究的研究对象是60岁以下的成年人,使用电脑/手机更多的是工作,而不是娱乐。随科技的发展,在全球范围内,从事电脑相关工作的人员迅速增长,使用电脑的时间也迅速增加[43]。工作有益于心理健康,可以带来自主感、成就感、归属感和幸福感[44-45]。第二,精神活跃的久坐行为对抑郁症状具有保护作用[46]。使用电脑/手机属于精神活跃的久坐行为[47]。因此,消极的久坐行为相关的消极情绪状态可能会增加抑郁的风险,而精神上活跃的久坐行为可能会降低风险,尽管能量消耗相当[47]。但是当电脑/手机使用时间 > 10 h/d时,与降低抑郁症状的风险无关。这可能与在电脑前花费比计划更多的时间,会给研究对象造成时间压力,忽视其他活动和个人需求造成精神超负荷有关[48]。

本研究发现在未调整和初步调整潜在混杂变量后,电视使用时间≥3 h/d与抑郁症状风险增加有关。同为电子屏幕使用时间,电视使用时间与随访期间抑郁症状的增加有关,而电脑/手机的使用时间与随访期间抑郁症状的降低有关,原因有以下几方面:第一,使用电脑/手机和电视对心脏代谢危险因素的影响不同,而抑郁症状与心血管疾病的危险因素有关。有3项研究报告称电视使用时间与心血管风险因素如血压、LDL-C、TG和胰岛素抵抗呈正相关,与HDL-C和载脂蛋白A1呈负相关[49-51]。但有研究表明使用电脑与心血管疾病的危险因素无关[52]。第二,使用电脑/手机和电视对认知功能的影响不同,抑郁症状与认知功能降低有关[53]。2项针对老年人的研究表明,使用电视和认知功能之间存在负相关,但使用电脑和认知功能之间存在正相关[54-55]。第三,使用电脑/手机和电视对社会交往的影响不同,抑郁症状与社会隔离密切相关[56]。电视使用时间更长的人社会互动少,影响了社会支持系统的发展,而社会支持系统已被证明对精神障碍有保护作用[57]。

本研究的优势包括前瞻性队列研究、大样本量、尽可能调整已知的混杂因素,数据资料来源于TCLSIH研究数据库,随访时间长,有抑郁症状风险人群有足够时间出现抑郁症状。但仍存在局限性。第一,网络成瘾和电子屏幕使用时间来自研究者自报,可能与实际情况存在回忆偏倚;第二,本研究使用基线时的电子屏幕时间作为分组依据,没有考虑研究对象电子屏幕时间长度会随时间发生变化;第三,电子屏幕时间没有分为工作日和周末,成年人工作日使用电脑/手机可能是工作而不是娱乐;第四,抑郁症状的评估采用自我报告问卷,而不是精神病学诊断。

综上所述,网络成瘾越严重、电视使用时间越长,出现抑郁症状的风险越高。而电脑/手机使用时间与降低抑郁症状的发生风险有关。通过监测电子屏幕时间及方式来防治抑郁症状是一个新思路,但这些数据无法阐明这种关联的本质,需要进一步地研究以了解电子屏幕如何影响成年人的抑郁症状。

利益冲突 所有作者声明无利益冲突

作者贡献声明 杜文秀:撰写文章、分析数据;顾叶青:分析数据、统计学分析;孟革:解释数据、项目管理;张卿、刘莉、武汉章:采集数据;牛凯军:构思设计、解释数据、统计学分析、修改文章、项目管理、经费支持

| [1] |

Williams DJ. No health without 'mental health'[J]. J Public Health (Oxf), 2018, 40(2): 444. DOI:10.1093/pubmed/fdx182 |

| [2] |

Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030[J]. PLoS Med, 2006, 3(11): e442. DOI:10.1371/journal.pmed.0030442 |

| [3] |

Ren XW, Yu SC, Dong WL, et al. Burden of depression in China, 1990-2017: Findings from the global burden of disease study 2017[J]. J Affect Disord, 2020, 268: 95-101. DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2020.03.011 |

| [4] |

Liu S, Wing YK, Hao YL, et al. The associations of long-time mobile phone use with sleep disturbances and mental distress in technical college students: a prospective cohort study[J]. Sleep, 2019, 42(2): 1-10. DOI:10.1093/sleep/zsy213 |

| [5] |

Wang X, Li YX, Fan HL. The associations between screen time-based sedentary behavior and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. BMC Public Health, 2019, 19(1): 1524. DOI:10.1186/s12889-019-7904-9 |

| [6] |

Saadati HM, Mirzaei H, Okhovat B, et al. Association between internet addiction and loneliness across the world: A meta-analysis and systematic review[J]. SSM Popul Health, 2021, 16: 100948. DOI:10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.100948 |

| [7] |

Wu CST, Wong HT, Yu KF, et al. Parenting approaches, family functionality, and internet addiction among Hong Kong adolescents[J]. BMC Pediatr, 2016, 16: 130. DOI:10.1186/s12887-016-0666-y |

| [8] |

Young KS. Psychology of computer use: XL. Addictive use of the Internet: a case that breaks the stereotype[J]. Psychol Rep, 1996, 79(3 Pt 1): 899-902. DOI:10.2466/pr0.1996.79.3.899 |

| [9] |

Ford ES, Caspersen CJ. Sedentary behaviour and cardiovascular disease: a review of prospective studies[J]. Int J Epidemiol, 2012, 41(5): 1338-1353. DOI:10.1093/ije/dys078 |

| [10] |

An RP, Yang Y. Diabetes diagnosis and screen-based sedentary behavior among US adults[J]. Am J Lifestyle Med, 2016, 12(3): 252-262. DOI:10.1177/1559827616650416 |

| [11] |

Yu B, Yu F, Su Q, et al. A J-shaped association between soy food intake and depressive symptoms in Chinese adults[J]. Clin Nutr, 2018, 37(3): 1013-1018. DOI:10.1016/j.clnu.2017.04.014 |

| [12] |

Yao ZX, Gu YQ, Zhang Q, et al. Estimated daily quercetin intake and association with the prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus in Chinese adults[J]. Eur J Nutr, 2019, 58(2): 819-830. DOI:10.1007/s00394-018-1713-2 |

| [13] |

Lee HC, Chiu HFK, Wing YK, et al. The Zung Self-rating depression scale: screening for depression among the Hong Kong Chinese elderly[J]. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol, 1994, 7(4): 216-220. DOI:10.1177/089198879400700404 |

| [14] |

Xia Y, Wang N, Yu B, et al. Dietary patterns are associated with depressive symptoms among Chinese adults: a case-control study with propensity score matching[J]. Eur J Nutr, 2017, 56(8): 2577-2587. DOI:10.1007/s00394-016-1293-y |

| [15] |

Xu L, Ren JM, Cheng M, et al. Depressive symptoms and risk factors in Chinese persons with type 2 diabetes[J]. Arch Med Res, 2004, 35(4): 301-307. DOI:10.1016/j.arcmed.2004.04.006 |

| [16] |

Zung WWK. A self-rating depression scale[J]. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 1965, 12(1): 63-70. DOI:10.1001/archpsyc.1965.01720310065008 |

| [17] |

Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjöström M, et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity[J]. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 2003, 35(8): 1381-1395. DOI:10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB |

| [18] |

Jia Q, Xia Y, Zhang Q, et al. Dietary patterns are associated with prevalence of fatty liver disease in adults[J]. Eur J Clin Nutr, 2015, 69(8): 914-921. DOI:10.1038/ejcn.2014.297 |

| [19] |

Li HP, Gu YQ, Wu XH, et al. Association between consumption of edible seaweeds and newly diagnosed non-alcohol fatty liver disease: The TCLSIH Cohort Study[J]. Liver Int, 2021, 41(2): 311-320. DOI:10.1111/liv.14655 |

| [20] |

Zhao HX, Du HL, Liu M, et al. Integrative proteomics-metabolomics strategy for pathological mechanism of vascular depression mouse model[J]. J Proteome Res, 2018, 17(1): 656-669. DOI:10.1021/acs.jproteome.7b00724 |

| [21] |

Ross ED, Stewart RS. Pathological display of affect in patients with depression and right frontal brain damage: An alternative mechanism[J]. J Nerv Ment Dis, 1987, 175(3): 165-172. DOI:10.1097/00005053-198703000-00007 |

| [22] |

Yoon S, Kleinman M, Mertz J, et al. Is social network site usage related to depression? A meta-analysis of Facebook-depression relations[J]. J Affect Disord, 2019, 248: 65-72. DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2019.01.026 |

| [23] |

Liu MY, Ren YP, Wei WL, et al. Changes of serotonin (5-HT), 5-HT2A receptor, and 5-HT transporter in the sprague-dawley rats of depression, myocardial infarction and myocardial infarction Co-exist with depression[J]. Chin Med J (Engl), 2015, 128(14): 1905-1909. DOI:10.4103/0366-6999.160526 |

| [24] |

Quandt G, Höfner G, Wanner KT. Synthesis and evaluation of N-substituted nipecotic acid derivatives with an unsymmetrical bis-aromatic residue attached to a vinyl ether spacer as potential GABA uptake inhibitors[J]. Bioorg Med Chem, 2013, 21(11): 3363-3378. DOI:10.1016/j.bmc.2013.02.056 |

| [25] |

Whybrow PC, Prange AJ Jr. A hypothesis of thyroid-catecholamine-receptor interaction: Its relevance to affective illness[J]. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 1981, 38(1): 106-113. DOI:10.1001/archpsyc.1981.01780260108012 |

| [26] |

Levine J, Panchalingam K, Rapoport A, et al. Increased cerebrospinal fluid glutamine levels in depressed patients[J]. Biol Psychiatry, 2000, 47(7): 586-593. DOI:10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00284-x |

| [27] |

McCarron RM, Shapiro B, Rawles J, et al. Depression[J]. Ann Intern Med, 2021, 174(5): ITC65-ITC80. DOI:10.7326/AITC202105180 |

| [28] |

Lazarevich I, Camacho MEI, Velázquez-Alva MDC, et al. Relationship among obesity, depression, and emotional eating in young adults[J]. Appetite, 2016, 107: 639-644. DOI:10.1016/j.appet.2016.09.011 |

| [29] |

Birk JL, Kronish IM, Moise N, et al. Depression and multimorbidity: Considering temporal characteristics of the associations between depression and multiple chronic diseases[J]. Health Psychol, 2019, 38(9): 802-811. DOI:10.1037/hea0000737 |

| [30] |

Jeon GS, Choi K, Cho SI. Impact of living alone on depressive symptoms in older Korean widows[J]. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2017, 14(10): 1191. DOI:10.3390/ijerph14101191 |

| [31] |

Lotfaliany M, Hoare E, Jacka FN, et al. Variation in the prevalence of depression and patterns of association, sociodemographic and lifestyle factors in community-dwelling older adults in six low-and middle-income countries[J]. J Affect Disord, 2019, 251: 218-226. DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2019.01.054 |

| [32] |

Park SJ, Rim SJ, Kim CE, et al. Effect of comorbid depression on health-related quality of life of patients with chronic diseases: A South Korean nationwide study (2007-2015)[J]. J Psychosom Res, 2019, 116: 17-21. DOI:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2018.11.004 |

| [33] |

Yi XY, Li GM. The longitudinal relationship between internet addiction and depressive symptoms in adolescents: a random-intercept cross-lagged panel model[J]. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2021, 18(24): 12869. DOI:10.3390/ijerph182412869 |

| [34] |

Yu B, Gu YQ, Bao X, et al. Distinct associations of computer/mobile devices use and TV watching with depressive symptoms in adults: A large population study in China[J]. Depress Anxiety, 2019, 36(9): 879-886. DOI:10.1002/da.22932 |

| [35] |

Javaeed A, Zafar MB, Iqbal M, et al. Correlation between Internet addiction, depression, anxiety and stress among undergraduate medical students in Azad Kashmir[J]. Pak J Med Sci, 2019, 35(2): 506-509. DOI:10.12669/pjms.35.2.169 |

| [36] |

杨林胜, 张志华, 郝加虎, 等. 青少年网络成瘾与自杀行为的相关关系[J]. 中华流行病学杂志, 2010, 31(10): 1115-1119. Yang LS, Zhang ZH, Hao JH, et al. Association between adolescent internet addiction and suicidal behaviors[J]. Chin J Epidemiol, 2010, 31(10): 1115-1119. DOI:10.3760/ema.j.issn.0254-6450.2010.10.010 |

| [37] |

Bhandari PM, Neupane D, Rijal S, et al. Sleep quality, internet addiction and depressive symptoms among undergraduate students in Nepal[J]. BMC Psychiatry, 2017, 17(1): 106. DOI:10.1186/s12888-017-1275-5 |

| [38] |

Alimoradi Z, Lin CY, Broström A, et al. Internet addiction and sleep problems: A systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Sleep Med Rev, 2019, 47: 51-61. DOI:10.1016/j.smrv.2019.06.004 |

| [39] |

Feng Q, Zhang QL, Du Y, et al. Associations of physical activity, screen time with depression, anxiety and sleep quality among Chinese college freshmen[J]. PLoS One, 2014, 9(6): e100914. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0100914 |

| [40] |

Şenormancı Ö, Saraçlı Ö, Atasoy N, et al. Relationship of Internet addiction with cognitive style, personality, and depression in university students[J]. Compr Psychiatry, 2014, 55(6): 1385-1390. DOI:10.1016/j.comppsych.2014.04.025 |

| [41] |

Veisani Y, Jalilian Z, Mohamadian F. Relationship between internet addiction and mental health in adolescents[J]. J Educ Health Promot, 2020, 9: 303. DOI:10.4103/jehp.jehp_362_20 |

| [42] |

Luciano A, Bond GR, Drake RE. Does employment alter the course and outcome of schizophrenia and other severe mental illnesses? A systematic review of longitudinal research[J]. Schizophr Res, 2014, 159(2/3): 312-321. DOI:10.1016/j.schres.2014.09.010 |

| [43] |

Elshaer N. Prevalence and associated factors related to arm, neck and shoulder complaints in a selected sample of computer office workers[J]. J Egypt Public Health Assoc, 2017, 92(4): 203-211. DOI:10.21608/EPX.2018.22041 |

| [44] |

Lee SA, Ju YJ, Han KT, et al. The association between loss of work ability and depression: a focus on employment status[J]. Int Arch Occup Environ Health, 2017, 90(1): 109-116. DOI:10.1007/s00420-016-1178-7 |

| [45] |

Boyatzis R, McKee A, Goleman D. Reawakening your passion for work[J]. Clin Leadersh Manag Rev, 2003, 17(2): 75-81. |

| [46] |

Hallgren M, Owen N, Stubbs B, et al. Passive and mentally-active sedentary behaviors and incident major depressive disorder: a 13-year cohort study[J]. J Affect Disord, 2018, 241: 579-585. DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2018.08.020 |

| [47] |

Hallgren M, Dunstan DW, Owen N. Passive versus mentally active sedentary behaviors and depression[J]. Exerc Sport Sci Rev, 2020, 48(1): 20-27. DOI:10.1249/JES.0000000000000211 |

| [48] |

Thomée S, Härenstam A, Hagberg M. Computer use and stress, sleep disturbances, and symptoms of depression among young adults-a prospective cohort study[J]. BMC Psychiatry, 2012, 12: 176. DOI:10.1186/1471-244X-12-176 |

| [49] |

Fung TT, Hu FB, Yu J, et al. Leisure-time physical activity, television watching, and plasma biomarkers of obesity and cardiovascular disease risk[J]. Am J Epidemiol, 2000, 152(12): 1171-1178. DOI:10.1093/aje/152.12.1171 |

| [50] |

Aadahl M, Kjær M, Jørgensen T. Influence of time spent on TV viewing and vigorous intensity physical activity on cardiovascular biomarkers. The Inter 99 study[J]. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil, 2007, 14(5): 660-665. DOI:10.1097/HJR.0b013e3280c284c5 |

| [51] |

Jakes RW, Day NE, Khaw KT, et al. Television viewing and low participation in vigorous recreation are independently associated with obesity and markers of cardiovascular disease risk: EPIC-Norfolk population-based study[J]. Eur J Clin Nutr, 2003, 57(9): 1089-1096. DOI:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601648 |

| [52] |

Nang EEK, Salim A, Wu Y, et al. Television screen time, but not computer use and reading time, is associated with cardio-metabolic biomarkers in a multiethnic Asian population: a cross-sectional study[J]. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act, 2013, 10: 70. DOI:10.1186/1479-5868-10-70 |

| [53] |

Yang X, Pan A, Gong J, et al. Prospective associations between depressive symptoms and cognitive functions in middle-aged and elderly Chinese adults[J]. J Affect Disord, 2020, 263: 692-697. DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2019.11.048 |

| [54] |

Hamer M, Stamatakis E. Prospective study of sedentary behavior, risk of depression, and cognitive impairment[J]. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 2014, 46(4): 718-723. DOI:10.1249/MSS.0000000000000156 |

| [55] |

Kesse-Guyot E, Charreire H, Andreeva VA, et al. Cross-sectional and longitudinal associations of different sedentary behaviors with cognitive performance in older adults[J]. PLoS One, 2012, 7(10): e47831. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0047831 |

| [56] |

Ge LX, Yap CW, Ong R, et al. Social isolation, loneliness and their relationships with depressive symptoms: A population-based study[J]. PLoS One, 2017, 12(8): e0182145. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0182145 |

| [57] |

Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC, Thisted RA. Perceived social isolation makes me sad: 5-year cross-lagged analyses of loneliness and depressive symptomatology in the Chicago Health, Aging, and Social Relations Study[J]. Psychol Aging, 2010, 25(2): 453-463. DOI:10.1037/a0017216 |

2022, Vol. 43

2022, Vol. 43