文章信息

- 伊丽萍, 薛建, 任少龙, 沈思, 李赵进, 钱晨, 林婉靖, 田健美, 张涛, 邵雪君, 赵根明.

- Yi Liping, Xue Jian, Ren Shaolong, Shen Si, Li Zhaojin, Qian Chen, Lin Wanjing, Tian Jianmei, Zhang Tao, Shao Xuejun, Zhao Genming

- 儿童肺炎支原体感染的临床特征及混合感染相关因素研究

- Clinical characteristics of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection and factors associated with co-infections in children

- 中华流行病学杂志, 2022, 43(9): 1448-1454

- Chinese Journal of Epidemiology, 2022, 43(9): 1448-1454

- http://dx.doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn112338-20220321-00210

-

文章历史

收稿日期: 2022-03-21

2. 苏州大学附属儿童医院, 苏州 215003;

3. 上海市重大传染病和生物安全研究院, 上海 200032

2. Soochow University Affiliated Children's Hospital, Suzhou 215003, China;

3. Shanghai Institute of Infectious Disease and Biosecurity, Shanghai 200032, China

社区获得性肺炎(community acquired pneumonia,CAP)是儿童期常见感染性疾病,是儿童住院的最常见原因[1]。肺炎支原体(Mycoplasma pneumoniae,Mp)是儿童CAP的重要病原之一,10%~40%的CAP由Mp感染引起[2-4]。Mp感染通常为自限性疾病,症状较轻,但也有不少病例可发展成重症或难治性肺炎,甚至导致死亡[5-6]。国内外研究显示,Mp常与其他病原体混合感染[2-3]。与单一病原感染相比,混合感染可能会导致更为严重的炎症反应及临床表现,使病程迁延或加重[1],提示Mp混合其他病原体感染可能为重症或难治性肺炎的原因之一[7]。本研究基于2018-2021年开展的儿童CAP住院病例病原学前瞻性监测和相关的调查,比较了Mp、细菌、病毒感染所致CAP病例在临床症状、相关实验室检测指标和治疗等方面的差异,描述了Mp混合感染的常见病原体,分析了Mp混合其他病原感染的相关因素,以期为临床肺炎诊治提供依据,对多病原感染肺炎预防提供参考建议。

对象与方法1. 研究对象及病例定义:2018年1月至2021年12月因CAP在苏州大学附属儿童医院(Soochow University Affiliated Children's Hospital,SCH)住院治疗的 < 16岁病例。CAP病例定义:《国际疾病分类第10版》编码为J09~J18(流感和肺炎)或J20~J22(其他急性下呼吸道感染)的病例。

2. 标本采集和实验室检测:病例入院24 h内采用无菌负压法抽取痰液1~2 ml,采用直接免疫荧光法检测呼吸道合胞病毒(respiratory syncytial virus,RSV)、副流感病毒和腺病毒,采用荧光定量PCR检测流感病毒(influenza virus,IFV)、衣原体、Mp、博卡病毒(human bocavirus,HBoV)、偏肺病毒和鼻病毒(rhinovirus,RhV);采用痰培养检测流感嗜血杆菌(Haemophilus influenzae,Hi)、肺炎链球菌(Streptococcus pneumoniae,SP)、金黄色葡萄球菌等细菌。病例入院时采集静脉血2 ml,部分病例于5~7 d后采集第二份静脉血,采用ELISA测定血清Mp-IgM和Mp-IgG,单份血清Mp-IgM > 1.1 S/CO或第二份血清Mp-IgG较急性期增高4倍及以上或鼻咽深部抽吸物Mp-DNA≥1×104拷贝/ml提示为Mp急性感染[8]。

3. 资料收集:由经过培训的项目人员在SCH呼吸科病房纳入符合CAP定义的病例,使用统一的调查问卷进行面对面问卷调查,结合住院病历,收集研究对象的人口学信息、既往病史、发病经过、临床症状、住院治疗等相关信息;通过SCH检验科信息系统查询病例的病原学检测结果。

4. 统计学分析:采用R 4.1.2软件进行统计学分析。符合正态分布的计量资料用x±s表示,多组间比较采用F检验;不符合正态分布的计量资料用M(Q1,Q3)表示,组间比较采用Kruskal-Wallis法。构成比或率的比较采用χ2检验。在混合感染相关因素分析中,先采用单因素logistic回归模型筛选危险因素,然后将单因素分析中P < 0.2的变量纳入多因素logistic回归,调整基础疾病史、早产、低出生体重等变量,得到相关因素的调整OR值及其95%CI。检验水准α=0.05。

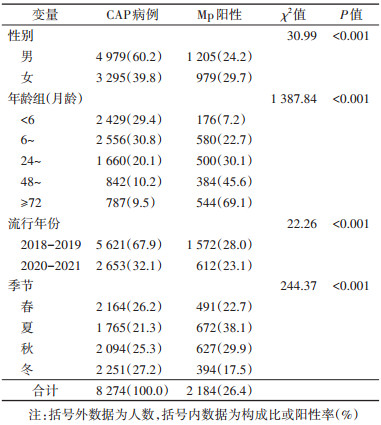

结果1. 基本情况:2018年1月至2021年12月,共纳入8 274名CAP住院病例,6 179例(74.7%)检出病原体,其中病毒检出率为44.6%(3 690/8 274),细菌检出率为31.7%(2 623/8 274),Mp检出率为26.4%(2 184/8 274)。Mp检出率女童高于男童(χ2=30.99,P < 0.001),随月龄增加而升高(χ2=1 387.84,P < 0.001),夏秋季检出率高于冬春季(χ2=244.37,P < 0.001)(表 1)。

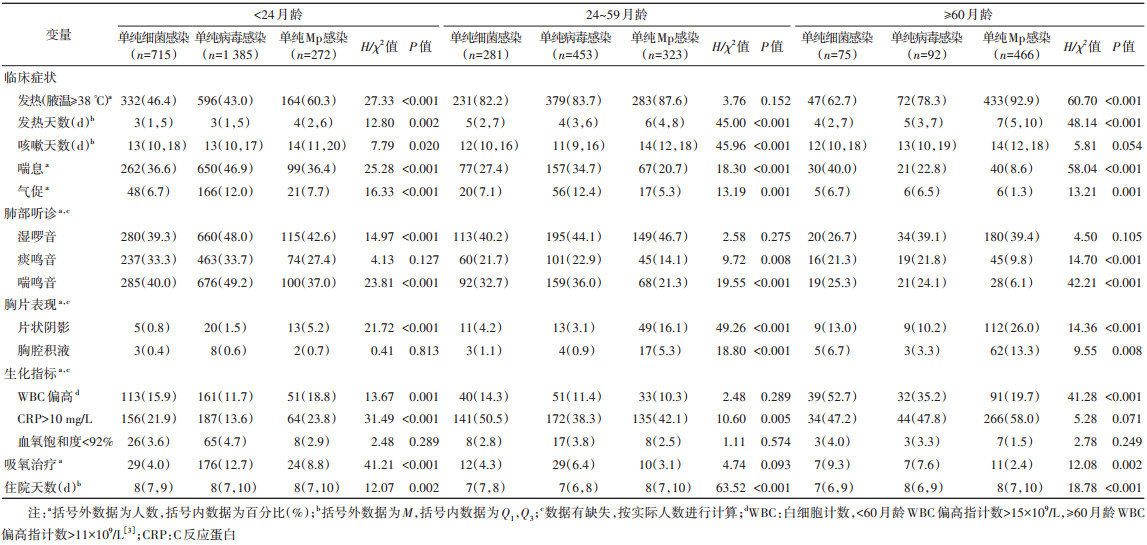

2. Mp、细菌、病毒感染病例临床特征:< 24、24~、≥60月龄单纯Mp感染病例发热率依次为60.3%、87.6%、92.9%(χ2=136.37,P < 0.001),喘息率分别为36.4%、20.7%、8.6%(χ2=85.44,P < 0.001),影像学检查肺部呈片状阴影的发生率依次为5.2%、16.1%、26.0%(χ2=48.48,P < 0.001),胸腔积液发生率分别为0.7%、5.3%、13.3%(χ2=42.18,P < 0.001),而接受吸氧治疗的比例依次为8.8%、3.1%、2.4%(χ2=19.16,P < 0.001)。< 24月龄单纯细菌、病毒、Mp感染病例发热天数M分别为3、3、4 d;24~月龄组分别为5、4、6 d;≥60月龄组分别为4、5、7 d(均P < 0.05)。此外,喘息、气促、肺部听诊呈喘鸣音、肺部呈片状阴影的发生率以及住院天数等指标在不同感染类型病例中的差异均有统计学意义(表 2)。

3. 单纯Mp感染与Mp混合感染的临床特征:2 184例Mp感染病例中,1 061例(48.6%)为单纯Mp感染,1 123例(51.4%)混合其他病原感染,其中,在 < 60月龄混合感染病例(870例)中,Mp与SP、RhV、Hi、HBoV和RSV的混合感染率较高,分别为26.6%、26.0%、18.9%、16.6%、13.8%;在≥60月龄混合感染病例(253例)中,Mp与RhV、SP、IFV和Hi混合感染率较高,分别为30.4%、23.3%、22.5%、16.2%。

< 60月龄单纯Mp感染组喘息发生率为27.9%,Mp混合1种细菌、1种病毒以及混合≥2种病原感染组喘息发生率分别为33.6%、42.1%和43.7%(P < 0.05),不同感染类型其肺部听诊呈痰鸣音和喘鸣音的比例差异有统计学意义(均P < 0.05)。≥60月龄单纯Mp感染组气促发生率为1.3%,混合感染组气促发生率分别为6.0%、5.0%和8.9%(P < 0.05)。见表 3。

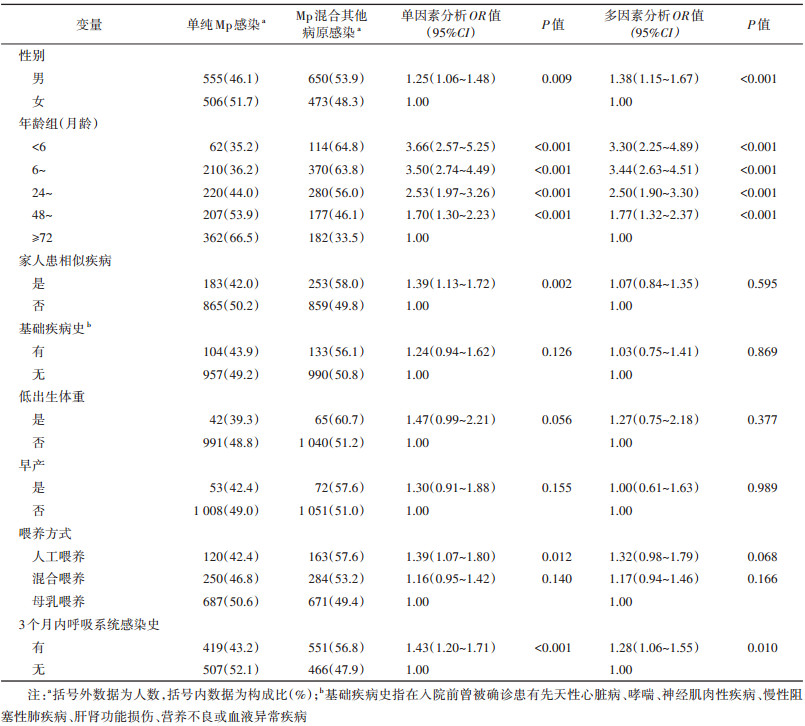

4. Mp混合其他病原感染的影响因素:男童(aOR=1.38,95%CI:1.15~1.67)、< 6月龄(aOR=3.30,95%CI:2.25~4.89)、6~月龄(aOR=3.44,95%CI:2.63~4.51)、24~月龄(aOR=2.50,95%CI:1.90~3.30)、48~71月龄(aOR=1.77,95%CI:1.32~2.37)及有3个月内呼吸系统感染史(aOR=1.28,95%CI:1.06~1.55)为Mp混合其他病原感染的相关因素(表 4)。

本研究所纳入CAP住院病例中,Mp检出率(26.4%)高于其他细菌或病毒,与苏州地区既往的研究(25.7%)基本一致[9],表明Mp是苏州地区住院CAP儿童的主要病原。研究表明,Mp的检出率具有一定的地区分布特征,来自中国[10]、新加坡[11]和希腊[12]的多中心研究同样发现Mp在住院CAP儿童中检出率最高,而美国儿童中Mp检出率(8%)略低[13]。本研究发现,不同年龄组病例病原谱有所差异,RSV、Mp、Hi、RhV和SP为2岁以下CAP病例最常见的病原体;Mp、SP、RhV、Hi和IFV为2~6岁病例的主要病原;而≥6岁CAP病例以Mp感染为主,检出率高达69.1%,这与一项在全国106个城市、277家哨点医院开展的呼吸道感染前瞻性监测研究结果基本一致[14]。虽然Mp检出率随年龄增加逐渐增高,但由于 < 5岁儿童肺炎就诊和住院的人次较高,对 < 5岁儿童造成的肺炎负担不容忽视。从季节分布来看,7-10月为Mp检出较高的月份,提示家长和托幼机构应关注儿童Mp肺炎的预防。

从本研究的临床症状和体征分析结果来看,发热、胸片片状阴影、胸腔积液等指标在24~59月龄和≥60月龄Mp感染病例中发生率更高;而喘息症状的发生率和接受吸氧治疗的比例在 < 24月龄Mp感染病例中更高。单纯Mp感染相较单纯细菌或病毒感染,发热天数更长,更易导致片状阴影,而肺部听诊呈喘鸣音的比例更低。上述结果与国内研究基本一致[15],新加坡一项研究同样发现Mp感染所致肺炎发热天数高于细菌、病毒性肺炎[11],但该研究仅检测较常检出的细菌和病毒,本研究所检测病原体更多,且按月龄组进行了分层分析,因此结果具有一定代表性。

多病原混合感染是否会增加疾病严重程度目前尚存在争议。本研究中,与同一年龄组单纯Mp感染病例相比,< 60月龄混合感染病例出现喘息症状及肺部听诊有痰鸣音和喘鸣音的比例更高;≥ 60月龄混合感染病例更易出现气促症状。同类研究发现混合病毒感染较Mp单独感染更易导致食欲下降[16],混合腺病毒感染较Mp单独感染发热和住院时间更长[17]。还有研究发现重症肺炎组混合感染率高于非重症组[18],提示混合感染可在一定程度上加重病例病情。

Mp混合感染检出率较高,本研究中混合感染占51.4%。对于混合感染的相关因素,国内外报道较少。本研究结果显示,男童较女童更容易发生混合感染。年龄是混合感染重要的因素,< 24月龄Mp感染病例中混合感染占60%以上,≥72月龄病例中混合感染占33.5%,差异可能与儿童呼吸系统和免疫功能的成熟度有关[7, 16]。有3个月内呼吸系统感染史也是混合感染发生的独立危险因素,反复呼吸道感染病例大多免疫力较差或存在基础疾病,容易发生同一病原体的反复感染或多种病原体混合感染。家中有其他家人患呼吸道感染时,可通过佩戴口罩等措施预防多病原感染肺炎发生;非母乳喂养的儿童应尤为注意增强免疫力以预防混合感染和重症肺炎。

本研究存在局限性。第一,研究现场SCH是当地唯一一家三甲儿童医院,虽有一定代表性,但仍有部分儿童会前往其他医院住院治疗,无法比较其他CAP住院儿童与本研究所纳入研究对象之间的差别;第二,SP、Hi等细菌为低年龄儿童咽部正常寄居菌群,所采集呼吸道标本的检测结果可能会受到咽部正常菌群的影响,可能对结果产生影响。

综上所述,本研究通过分析2018-2021年SCH儿童CAP住院病例的临床资料,进一步明确了Mp在CAP中的病原作用和Mp感染的临床特征,并对混合感染肺炎的临床严重性及多病原混合感染的危险因素进行了探索,建议相关机构采取针对性的防控措施以降低儿童肺炎发病和住院率。

利益冲突 所有作者声明无利益冲突

作者贡献声明 伊丽萍:论文撰写;薛建、任少龙、沈思:数据整理;李赵进、钱晨、林婉靖:统计学分析;田健美、张涛、邵雪君、赵根明:研究指导、论文修改、经费支持

| [1] |

中华医学会儿科学分会呼吸学组, 《中华儿科杂志》编辑委员会. 儿童社区获得性肺炎管理指南(2013修订)(上)[J]. 中华儿科杂志, 2013, 51(10): 745-752. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0578-1310.2013.10.006 |

| [2] |

中华医学会儿科学分会呼吸学组, 《中华实用儿科临床杂志》编辑委员会. 儿童肺炎支原体肺炎诊治专家共识(2015年版)[J]. 中华实用儿科临床杂志, 2015, 30(17): 1304-1308. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.2095-428X.2015.17.006 |

| [3] |

Kutty PK, Jain S, Taylor TH, et al. Mycoplasma pneumoniae among children hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2019, 68(1): 5-12. DOI:10.1093/cid/ciy419 |

| [4] |

Sauteur PMM, Krautter S, Ambroggio L, et al. Improved diagnostics help to identify clinical features and biomarkers that predict Mycoplasma pneumoniae community-acquired pneumonia in children[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2020, 71(7): 1645-1654. DOI:10.1093/cid/ciz1059 |

| [5] |

Choi YJ, Jeon JH, Oh JW. Critical combination of initial markers for predicting refractory Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia in children: a case control study[J]. Respir Res, 2019, 20(1): 193. DOI:10.1186/s12931-019-1152-5 |

| [6] |

Zheng Y, Hua LL, Zhao QN, et al. The level of D-Dimer is positively correlated with the severity of Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia in children[J]. Front Cell Infect Microbiol, 2021, 11: 687391. DOI:10.3389/fcimb.2021.687391 |

| [7] |

Zhang XX, Chen ZR, Gu WJ, et al. Viral and bacterial co-infection in hospitalised children with refractory Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia[J]. Epidemiol Infect, 2018, 146(11): 1384-1388. DOI:10.1017/S0950268818000778 |

| [8] |

Li QL, Dong HT, Sun HM, et al. The diagnostic value of serological tests and real-time polymerase chain reaction in children with acute Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection[J]. Ann Transl Med, 2020, 8(6): 386. DOI:10.21037/atm.2020.03.121 |

| [9] |

季伟, 陈正荣, 周卫芳, 等. 2005-2011年苏州地区急性呼吸道感染住院儿童病原学研究[J]. 中华预防医学杂志, 2013, 47(6): 497-503. Ji W, Chen ZR, Zhou WF, et al. Etiology of acute respiratory tract infection in hospitalized children in Suzhou from 2005 to 2011[J]. Chin J Prev Med, 2013, 47(6): 497-503. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-9624.2013.06.005 |

| [10] |

Hao OM, Wang XF, Liu JP, et al. Etiology of community-acquired pneumonia in 1 500 hospitalized children[J]. J Med Virol, 2018, 90(3): 421-428. DOI:10.1002/jmv.24963 |

| [11] |

Chiang WC, Teoh OH, Chong CY, et al. Epidemiology, clinical characteristics and antimicrobial resistance patterns of community-acquired pneumonia in 1 702 hospitalized children in Singapore[J]. Respirology, 2007, 12(2): 254-261. DOI:10.1111/j.1440-1843.2006.01036.x |

| [12] |

Otheo E, Rodriguez M, Moraleda C, et al. Viruses and Mycoplasma pneumoniae are the main etiological agents of community-acquired pneumonia in hospitalized pediatric patients in Spain[J]. Pediatr Pulmonol, 2022, 57(1): 253-263. DOI:10.1002/ppul.25721 |

| [13] |

Jain S, Williams DJ, Arnold SR, et al. Community-acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalization among U. S. children[J]. N Engl J Med, 2015, 372(9): 835-845. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa1405870 |

| [14] |

Li ZJ, Zhang HY, Ren LL, et al. Etiological and epidemiological features of acute respiratory infections in China[J]. Nat Commun, 2021, 12(1): 5026. DOI:10.1038/s41467-021-25120-6 |

| [15] |

周冬娟. 病毒性、细菌性、肺炎支原体及混合感染性肺炎临床特征比较[D]. 苏州: 苏州大学, 2018. Zhou DJ. Comparison of clinical characteristics of viral, bacterial, mycoplasma pnenmoniae and mixed infectious pneumonia[D]. Suzhou: Soochow University, 2018. |

| [16] |

Zhao MC, Wang L, Qiu FZ, et al. Impact and clinical profiles of Mycoplasma pneumoniae co-detection in childhood community-acquired pneumonia[J]. BMC Infect Dis, 2019, 19(1): 835. DOI:10.1186/s12879-019-4426-0 |

| [17] |

Gao JJ, Xu LL, Xu BP. Human adenovirus Coinfection aggravates the severity of Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia in children[J]. BMC Infect Dis, 2020, 20(1): 420. DOI:10.1186/s12879-020-05152-x |

| [18] |

Song Q, Xu BP, Shen KL. Effects of bacterial and viral co-infections of Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia in children: analysis report from Beijing Children's Hospital between 2010 and 2014[J]. Int J Clin Exp Med, 2015, 8(9): 15666-15674. |

2022, Vol. 43

2022, Vol. 43