文章信息

- 李燕婕, 曹梦迪, 王鑫, 雷林, 彭绩, 石菊芳.

- Li Yanjie, Cao Mengdi, Wang Xin, Lei Lin, Peng Ji, Shi Jufang

- 基于筛查干预角度的中国人群结直肠癌所致伤残调整寿命年负担分析

- Thirty-year changes in disability adjusted life years for colorectal cancer in China: a screening perspective analysis

- 中华流行病学杂志, 2022, 43(9): 1381-1387

- Chinese Journal of Epidemiology, 2022, 43(9): 1381-1387

- http://dx.doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn112338-20220504-00377

-

文章历史

收稿日期: 2022-05-04

2. 深圳市慢性病防治中心肿瘤防控科,深圳 518020

2. Department of Cancer Prevention and Control, Shenzhen Center for Chronic Disease Control, Shenzhen 518020, China

结直肠癌是全球范围发病排第3位的恶性肿瘤,在中国的发病率排第3位且逐年上升[1-2]。近年来有多项结直肠癌所致疾病负担报道,分别聚焦于中国结直肠癌发病、死亡、生存、危险因素等方面,但针对伤残调整寿命年(disability adjusted life years,DALY)这一综合指标的评价相对较少[3-10]。全球疾病负担(Global burden of disease,GBD)项目团队新近发布了全球结直肠癌疾病负担[11],包括中国人群数据但国家特异性信息细节有限。根据现有证据提示,结直肠癌是筛查效果较好的癌种之一[12-14]。结直肠癌筛查在多个发达国家已推行全人群项目多年[15],在中国也日益受到重视,现有多项国家重大公共卫生服务项目和个别地市级全市(省)适龄人群结直肠癌筛查项目在组织推行[16]。通过国际对比,可为中国相关工作推行提供更多证据。因此,本研究基于GBD2019数据,结合筛查干预,分析中国人群结直肠癌所致负担的现况、既往与未来,并行国际比较,为结直肠癌疾病负担及其筛查干预提供参考。

资料与方法1. 资料来源:来源于GBD2019。GBD2019利用统一、可比的方法对全球204个国家和地区的302种死因、369种疾病和伤害以及87种风险因素的疾病负担进行了综合评估,提供了1990-2019年不同区域、年龄和性别人群的详细数据[17-18]。本研究从中摘录中国人群1990-2019年结直肠癌所致DALY负担数据进行分析预测。

2. 指标及统计学分析:①核心指标:包括DALY数、过早死亡损失寿命年(years of life lost,YLL)数和伤残损失寿命年(years lived with disability,YLD)数、采用世界标准人口[17]标化后的DALY率(世标率)以及平均年度变化百分比(average annual percent change,AAPC);本研究也提炼了归因于不同危险因素的DALY数百分比信息,该指标是GBD根据比较风险评估理论框架,以疾病负担相关指标、各类危险因素的一般及理论最低风险暴露水平、暴露引起结果的相对危险度(RR)估算[18]。②统计学分析:描述中国2019年结直肠癌所致DALY数、世标率及不同亚组值。分析1990-2019年DALY率变化趋势,并以大多数国家全人群结直肠癌筛查的启动年份(2006年)为时间节点,通过AAPC的变化行筛查效果角度的国际比较。③预测相关:应用Joinpoint回归模型[19],分析1990-2019年不同年龄别(5岁一组,共17组)DALY率的AAPC,然后选取普遍有统计学意义(P < 0.05)的年份拐点间的AAPC值,结合联合国人口司预测的中国人口年龄别数据[20],预测中国2020-2030年结直肠癌所致DALY负担情况。

3. 癌症筛查相关信息来源及处理:①了解结直肠癌筛查推荐或应用的年龄范围内中国结直肠癌所致DALY总负担中占多大比例,以比较初判现行筛查对降低当地结直肠癌负担的有效程度;年龄范围的选择主要参照中国主要国家重大公共服务筛查项目(农村和城市项目)、国家癌症中心推出的结直肠癌筛查与早诊早治指南、发达国家指南最多推荐人群筛查年龄范围等。②在趋势分析时,同时选择呈现其他国家的趋势数据及其对应人群结直肠癌筛查项目启动年份并结合覆盖率、参与率等进行讨论,通过国际比较来为中国的结直肠癌筛查工作提供借鉴和方向。

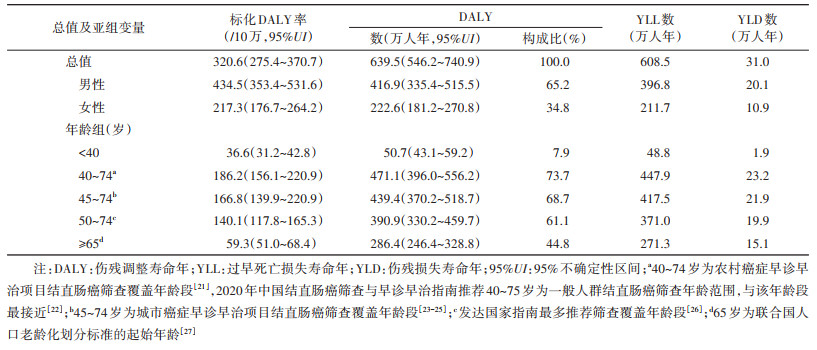

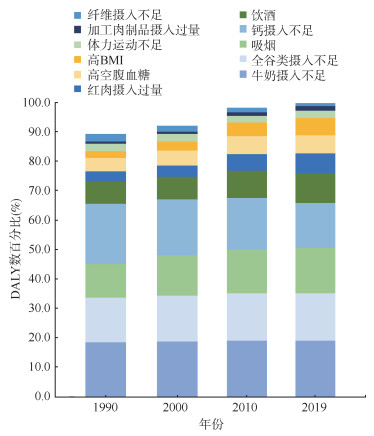

结果1. 现状分析:2019年中国人群结直肠癌所致DALY总数为639.5万人年(标化DALY率为320.6/10万),占全球结直肠癌负担的26.3%,占中国全部癌种负担的9.5%。其中,YLL和YLD数分别为608.5万人年和31.0万人年,分别占DALY总数的95.2%和4.8%;在DALY总数中,男性占65.2%,≥65岁的老龄人口占44.8%。危险因素归因方面,牛奶摄入不足是目前中国人群结直肠癌所致DALY归因的首位因素(2019年占比为19.1%),其次是全谷类摄入不足(15.9%)和吸烟(15.4%)。

结合筛查年龄相关分析,中国中央财政支持的农村癌症早诊早治项目推荐的筛查年龄段为40~74岁[21][国家癌症中心结直肠癌筛查指南推荐的筛查起始年龄(40~75岁)与之接近[22]],其可覆盖中国全人群结直肠癌所致DALY总数的73.7%;中国城市癌症早诊早治项目推荐的筛查年龄为45~74岁[23-25],其可覆盖中国结直肠癌所致DALY总数的68.7%,多数有国家级全人群结直肠癌筛查项目的发达国家推荐的筛查年龄以50~74岁多见[26],该年龄段可覆盖中国结直肠癌所致DALY总数的61.1%。见表 1。

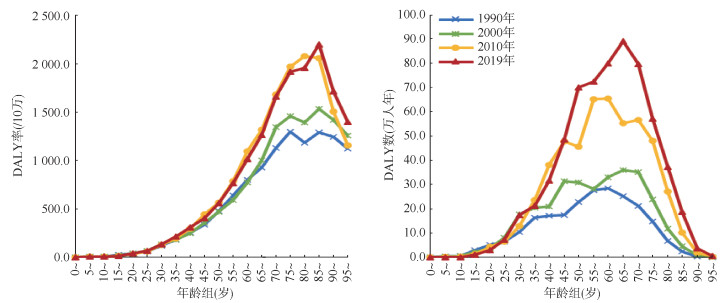

2. 既往趋势:中国结直肠癌所致DALY总数由1990年的227.1万人年增长至2019年的639.5万人年,30年间增幅达181.5%。DALY总数内部构成方面,YLD的占比由2.1%增至4.8%,男性的占比由54.5%上升为65.2%(图 1)。年龄分布方面,相比1990年,2019年出现DALY负担总数量的明显增加以及年龄峰值的后移(图 2),其中≥65岁的老龄人口占比由31.3%增至44.8%[27]。此外,结直肠癌归因于危险因素的DALY数百分比方面,30年间上升幅度最大的因素依次是高BMI、红肉摄入过量和加工肉制品摄入过量(增幅依次为151.1%、86.4%和78.8%)。见图 3。

|

| 注:DALY:伤残调整寿命年;YLL:过早死亡损失寿命年;YLD:伤残损失寿命年;图中的百分数为构成比(%) 图 1 1990-2019年中国人群结直肠癌所致DALY数内部构成变化 |

|

| 注:DALY:伤残调整寿命年 图 2 1990-2019年中国人群结直肠癌所致DALY负担的年龄别分布变化 |

|

| 注:DALY:伤残调整寿命年 图 3 1990-2019年中国人群结直肠癌归因于不同危险因素的DALY数百分比变化 |

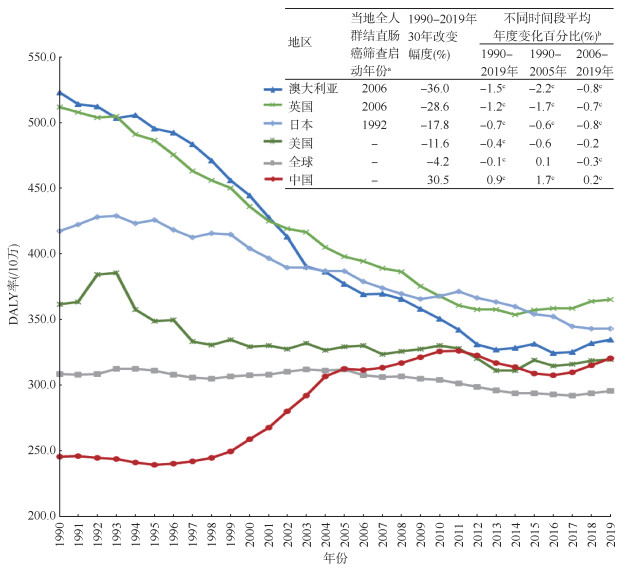

3. 筛查干预相关分析:就结直肠癌所致DALY率,中国1990年为245.6/10万,2019年为320.6/10万,增幅达30.5%,而同期全球数据总体呈下降趋势,降幅为4.2%。作为参照,已开展全人群筛查的澳大利亚(2006年启动)[28]、英国(2006年)[29]和日本(1992年,结直肠癌筛查被纳入政府支持的全民健康保险)[30],DALY率降幅分别为36.0%、28.6%和17.8%;目前尚无全人群结直肠癌筛查的美国(预防保健项目主要依靠商业保险)[31],其降幅略小,为11.6%。不同人群在30年间整体以及不同时间段DALY率改变的AAPC信息(以所列国家开展全人群结直肠癌筛查起始年份最多的2006年为例进行分界呈现)。见图 4。

|

| 注:DALY:伤残调整寿命年;a-:表示暂无全人群结直肠癌筛查项目;b最右两列的年份分割以所列国家开展全人群筛查起始年份最多的2006年为例;cP < 0.05 图 4 1990-2019年不同人群结直肠癌所致DALY负担趋势变化及筛查开展年份比较 |

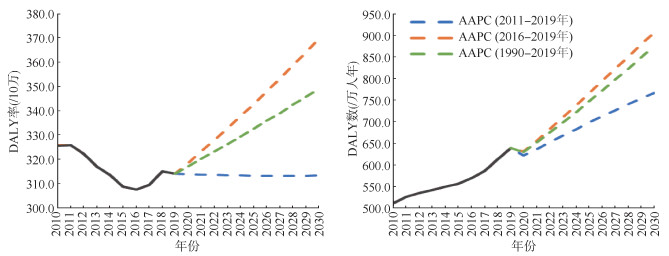

4. 未来预测:针对不同年龄组(5岁一组)的AAPC分析提示,30年间的2011年和2016年为普遍具有统计学意义(P < 0.05)的拐点,获得对应1990-2019、2011-2019和2016-2019年时间段的具体AAPC值(以50~54岁组为例,对应AAPC分别为0.50%、-0.20%和1.40%)。然后基于这3种增长趋势,进一步预测分析提示,中国结直肠癌所致DALY总数在2030年将达到766.6万人年~906.6万人年,较2019年增加了19.9%~41.8%。不同时段预测的中国人群结直肠癌所致标化DALY率差异明显,其中基于1990-2019年和2016-2019年的趋势预测2030年的标化DALY率较2019年呈现上升趋势,分别为349.0/10万和369.7/10万;使用2011- 2019年趋势预测的2030年标化DALY率为313.4/10万,与2019年相比略有下降。见图 5。

|

| 注:DALY:伤残调整寿命年;AAPC:平均年度变化百分比 图 5 2030年中国人群结直肠癌所致DALY负担预测 |

本研究尝试从筛查干预的视角,应用GBD 2019公开信息,以DALY这一综合性指标分析中国结直肠癌所致DALY负担现况及长期趋势。分析结果提示,既往30年中国结直肠癌所致DALY负担持续增加,人口老龄化及伴随失能会让负担更重。目前本土筛查指南推荐年龄可覆盖七成DALY负担来源人群,但实际人群筛查覆盖有限。其他国家结直肠癌所致DALY负担的下降与筛查开展密不可分,提示尽快扩大本土结直肠癌有效筛查覆盖率的重要性。

结直肠癌这一单一癌种所致DALY负担占到中国全部癌种所致负担的近一成,不容忽视,这一现象与其目前在中国较高的发病率、相比其他癌种更高的生存时间、可归因生活方式的改变(BMI等)等因素不无关系[11, 32-33]。分析也提示,伴随人口老龄化,若无扩大的有效筛查,这一负担在未来几十年间还将加重。为了降低总的结直肠癌所致DALY负担,筛查年龄范围的宽窄、人群政策覆盖的高低、人群实际的参与意愿、政府或多方可投入的资源或支付意愿/能力,还需要综合平衡评价。目前中国两大结直肠癌筛查相关公卫项目和指南推荐的筛查年龄可以覆盖约七成DALY负担来源人群,比欧洲地区、美国多推荐的50~74岁有更广的覆盖和更大的潜在效果;然而,中国各级组织性结直肠癌筛查在全国40~74岁人群中的单一年度的覆盖率据初步估计仍不到1%,全国适龄人群对于结直肠癌筛查服务的可及性仍然有限。

目前国内外已有多项高级别证据证明:筛查可有效降低结直肠癌死亡率且具有长期效应[13-14];提高结直肠癌筛查的覆盖率,能预防更多病例发生,挽救生命[34]。降低结直肠癌的发病率与死亡率均能有效缓解DALY负担,本研究的国际趋势分析比较再现了这一效果。澳大利亚和英国已实施全人群结直肠癌筛查超过15年[28-29],参与率(接受筛查人数除以被邀请参加筛查人数)分别达到45.5%(2016年)和55.4%(2017年)[8, 15],其30年间的DALY率下降幅度均大于15%;细化到具体时段,两国2006年前的DALY降幅下降较快,其可能原因是在开展全人群筛查前,两国已有一定覆盖范围的区域性筛查;社会学、经济学等相关因素也存在一定的影响[35-36]。日本比以上两国开展全人群筛查更早,参与率也尚可(44.2%,2019年[37]),但30年间整体下降幅度略小,可能原因是近年来饮食、生活习惯改变导致危险因素暴露增加所致[38]。在所列经济发达国家中,美国30年间的DALY率的总下降幅度最小,与其尚未开展全人群筛查有关,该国目前推行的主要是基于商业保险的自发性筛查,以肠镜检查为主要初筛,该技术一定程度上也限制了参与率的提升[39]。中国自1990年至今DALY负担均呈现上升趋势,2006年后增幅渐缓。这一现象与中国人群生活方式、饮食等一级预防因素的改变相关,也与中国结直肠癌筛查服务可及性有限关系密切。因此坚持开展结直肠癌筛查,借鉴发达国家经验,并持续扩大筛查覆盖面,在未来可能进一步缓解中国人群结直肠癌所致DALY负担。

本研究从群体水平上归纳DALY负担与筛查干预的效果,存在类似生态学研究方法学方面的局限性。分析借力GBD公开信息平台,也受其局限存在如归因危险因素所列不全等问题。此外,预测分析主要是通过人口结构和规模以及既往无大范围筛查开展的DALY趋势变化进行预测,未考虑其他影响因素以及宏观政策影响(如宫颈癌筛查被纳入国家基本公共卫生服务项目等类似支持行动)。

利益冲突 所有作者声明无利益冲突

作者贡献声明 李燕婕:研究设计、数据整理、统计学分析、论文撰写;曹梦迪、王鑫:数据整理、统计学分析;雷林、彭绩:论文修改、经费支持;石菊芳:研究设计、研究指导、论文修改、经费支持

| [1] |

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020:GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2021, 71(3): 209-249. DOI:10.3322/caac.21660 |

| [2] |

Zheng RS, Zhang SW, Zeng HM, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality in China, 2016[J]. J Natl Cancer Cent, 2022, 2(1): 1-9. DOI:10.1016/j.jncc.2022.02.002 |

| [3] |

Qiu HB, Cao SM, Xu RH. Cancer incidence, mortality, and burden in China: a time-trend analysis and comparison with the United States and United Kingdom based on the global epidemiological data released in 2020[J]. Cancer Commun (Lond), 2021, 41(10): 1037-1048. DOI:10.1002/cac2.12197 |

| [4] |

Li N, Lu B, Luo CY, et al. Incidence, mortality, survival, risk factor and screening of colorectal cancer: a comparison among China, Europe, and northern America[J]. Cancer Lett, 2021, 522: 255-268. DOI:10.1016/j.canlet.2021.09.034 |

| [5] |

Wang W, Yin P, Liu YN, et al. Mortality and years of life lost of colorectal cancer in China, 2005-2020:findings from the national mortality surveillance system[J]. Chin Med J (Engl), 2021, 134(16): 1933-1940. DOI:10.1097/CM9.0000000000001625 |

| [6] |

Yin J, Bai ZG, Zhang J, et al. Burden of colorectal cancer in China, 1990-2017:findings from the global burden of disease study 2017[J]. Chin J Cancer Res, 2019, 31(3): 489-498. DOI:10.21147/j.issn.1000-9604.2019.03.11 |

| [7] |

Douaiher J, Ravipati A, Grams B, et al. Colorectal cancer-global burden, trends, and geographical variations[J]. J Surg Oncol, 2017, 115(5): 619-630. DOI:10.1002/jso.24578 |

| [8] |

王红, 曹梦迪, 刘成成, 等. 中国人群结直肠癌疾病负担: 近年是否有变?[J]. 中华流行病学杂志, 2020, 41(10): 1633-1642. Wang H, Cao MD, Liu CC, et al. Disease burden of colorectal cancer in China: any changes in recent years?[J]. Chin J Epidemiol, 2020, 41(10): 1633-1642. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.cn112338-20200306-00273 |

| [9] |

王娜, 刘洁, 李晓东, 等. 中国1990~2019年结直肠癌疾病负担分析[J]. 中国循证医学杂志, 2021, 21(5): 520-524. Wang N, Liu J, Li XD, et al. An analysis of disease burden of colorectal cancer in China from 1990 to 2019[J]. Chin J Evidence-Based Med, 2021, 21(5): 520-524. DOI:10.7507/1672-2531.202012006 |

| [10] |

黄钊慰, 薛明劲, 胡雨迪, 等. 1990-2019年中国结直肠癌归因于各类危险因素的疾病负担分析与模型预测[J]. 中华疾病控制杂志, 2022, 26(1): 7-13. Huang ZW, Xue MJ, Hu YD, et al. Analysis and model prediction of disease burden attributable to various risk factors for colorectal cancer in China from 1990 to 2019[J]. Chin J Dis Control Prev, 2022, 26(1): 7-13. DOI:10.16462/j.cnki.zhjbkz.2022.01.002 |

| [11] |

GBD 2019 Colorectal Cancer Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of colorectal cancer and its risk factors, 1990-2019:a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019[J]. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2022, 7(7): 627-647. DOI:10.1016/S2468-1253(22)00044-9 |

| [12] |

Dekker E, Tanis PJ, Vleugels JLA, et al. Colorectal cancer[J]. Lancet, 2019, 394(10207): 1467-1480. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32319-0 |

| [13] |

Shaukat A, Mongin SJ, Geisser MS, et al. Long-term mortality after screening for colorectal cancer[J]. N Engl J Med, 2013, 369(12): 1106-1114. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa1300720 |

| [14] |

Kanth P, Inadomi JM. Screening and prevention of colorectal cancer[J]. BMJ, 2021, 374: n1855. DOI:10.1136/bmj.n1855 |

| [15] |

Navarro M, Nicolas A, Ferrandez A, et al. Colorectal cancer population screening programs worldwide in 2016:an update[J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2017, 23(20): 3632-3642. DOI:10.3748/wjg.v23.i20.3632 |

| [16] |

曹毛毛, 陈万青. 坚持政府主导推进中国癌症筛查发展[J]. 中国肿瘤, 2021, 30(11): 803-805. Cao MM, Chen WQ. Promoting government-supported cancer screening pro-grams in China[J]. China Cancer, 2021, 30(11): 803-805. DOI:10.11735/j.issn.1004-0242.2021.11.A001 |

| [17] |

GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019:a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019[J]. Lancet, 2020, 396(10258): 1204-1222. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9 |

| [18] |

GBD 2019 Risk Factors Collaborators. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019:a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019[J]. Lancet, 2020, 396(10258): 1223-1249. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30752-2 |

| [19] |

Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences National Cancer Institute. Joinpoint help manual 4.7.00[EB/OL]. [2022-04-29]. https://surveillance.cancer.gov/joinpoint/JoinpointHelp4.7.0.0.pdf.

|

| [20] |

United Nations: Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Dynamics. World population prospects 2019[EB/OL]. [2022-04-29]. https://population.un.org/wpp/DataQuery/.

|

| [21] |

卫生部疾病预防控制局, 癌症早诊早治项目专家委员会. 癌症早诊早治项目技术方案(2011年版)[M]. 北京: 人民卫生出版社, 2011. Bureau of Disease Control and Prevention of the Ministry of Health, Expert Committee of Cancer Early Diagnosis and Early Treatment Project. Technical protocol of early diagnosis and early treatment of cancer program (2011 edition)[M]. Beijing: People's Medical Publishing House, 2011. |

| [22] |

陈万青, 李霓, 兰平, 等. 中国结直肠癌筛查与早诊早治指南(2020, 北京)[J]. 中国肿瘤, 2021, 30(1): 1-28. Chen WQ, Li N, Lan P, et al. China guideline for the screening, early detection and early treatment of colorectal cancer (2020, Beijing)[J]. China Caner, 2021, 30(1): 1-28. DOI:10.11735/j.issn.1004-0242.2021.01.A001 |

| [23] |

代敏, 石菊芳, 李霓. 中国城市癌症早诊早治项目设计及预期目标[J]. 中华预防医学杂志, 2013, 47(2): 179-182. Dai M, Shi JF, Li N. Design and expected target of early diagnosis and treatment project of urban cancer in China[J]. Chin J Prev Med, 2013, 47(2): 179-182. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-9624.2013.02.018 |

| [24] |

赫捷. 中国人群癌症筛查工作指导手册[M]. 北京: 人民卫生出版社, 2021. He J. Cancer screening handbook in China[M]. Beijing: People's Medical Publishing House, 2021. |

| [25] |

国家癌症中心, 中国医学科学院肿瘤医院. 城市癌症早诊早治项目技术方案(2020年版)[M]. 北京: 国家癌症中心, 2020. National Cancer Center, Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences. Technical protocol for cancer screening program in urban China (2020 edition)[M]. Beijing: National Cancer Center, 2020. |

| [26] |

Ebell MH, Thai TN, Royalty KJ. Cancer screening recommendations: an international comparison of high income countries[J]. Public Health Rev, 2018, 39: 7. DOI:10.1186/s40985-018-0080-0 |

| [27] |

Economic and social implications of population aging[Z]. New York; UN. 1988.

|

| [28] |

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Cancer screening[EB/OL]. [2022-04-29]. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports-data/health-welfare-services/cancer-screening/about.

|

| [29] |

NHS Cancer Screening Programmes. NHS bowel cancer screening (BCSP) programme: detailed information[EB/OL]. [2022-04-29]. https://www.gov.uk/topic/population-screening-programmes/bowel.

|

| [30] |

Takahashi N, Nakao M. Social-life factors associated with participation in screening and further assessment of colorectal cancer: A nationwide ecological study in Japanese municipalities[J]. SSM-Population Health, 2021, 15: 100839. DOI:10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.100839 |

| [31] |

Montminy EM, Karlitz JJ, Landreneau SW. Progress of colorectal cancer screening in United States: past achievements and future challenges[J]. Prev Med, 2019, 120: 78-84. DOI:10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.12.004 |

| [32] |

Zhou JC, Zheng RS, Zhang SW, et al. Colorectal cancer burden and trends: comparison between China and major burden countries in the world[J]. Chin J Cancer Res, 2021, 33(1): 1-10. DOI:10.21147/j.issn.1000-9604.2021.01.01 |

| [33] |

Zeng HM, Chen WQ, Zheng RS, et al. Changing cancer survival in China during 2003-15:a pooled analysis of 17 population-based cancer registries[J]. Lancet Glob Health, 2018, 6(5): e555-567. DOI:10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30127-X |

| [34] |

Lew JB, St John DJB, Xu XM, et al. Long-term evaluation of benefits, harms, and cost-effectiveness of the national bowel cancer screening program in Australia: a modelling study[J]. Lancet Public Health, 2017, 2(7): e331-340. DOI:10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30105-6 |

| [35] |

Mcclements PL, Madurasinghe V, Thomson CS, et al. Impact of the UK colorectal cancer screening pilot studies on incidence, stage distribution and mortality trends[J]. Cancer Epidemiol, 2012, 36(4): e232-242. DOI:10.1016/j.canep.2012.02.006 |

| [36] |

Weller D, Thomas D, Hiller J, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer using an immunochemical test for faecal occult blood: results of the first 2 years of a south Australian programme[J]. Aust N Z J Surg, 1994, 64(7): 464-469. DOI:10.1111/j.1445-2197.1994.tb02257.x |

| [37] |

Ross WA. Colorectal cancer screening in evolution: Japan and the USA[J]. J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2010, 25(Suppl 1): S49-56. DOI:10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06221.x |

| [38] |

National Cancer Center Japan. Cancer screening[EB/OL]. [2022-04-29]. https://ganjoho.jp/public/pre_scr/screening/index.html.

|

| [39] |

Bello RJ, Chang GJ, Massarweh NN. Colorectal cancer screening in the US-still putting the cart before the horse?[J/OL]. JAMA Oncol, 2022[2022-05-05]. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2022.0500.

|

2022, Vol. 43

2022, Vol. 43