文章信息

- 王月清, 肖梦, 杨海铭, 宋明钰, 赵禹碹, 庞元捷, 高文静, 曹卫华, 黄涛, 余灿清, 吕筠, 李立明, 孙点剑一.

- Wang Yueqing, Xiao Meng, Yang Haiming, Song Mingyu, Zhao Yuxuan, Pang Yuanjie, Gao Wenjing, Cao Weihua, Huang Tao, Yu Canqing, Lyu Jun, Li Liming, Sun Dianjianyi

- 衰老表型全基因组关联研究综述

- Review of genome-wide association research of aging phenotypes

- 中华流行病学杂志, 2022, 43(8): 1338-1342

- Chinese Journal of Epidemiology, 2022, 43(8): 1338-1342

- http://dx.doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn112338-20211109-00867

-

文章历史

收稿日期: 2021-11-09

2. 北京大学公众健康与重大疫情防控战略研究中心, 北京 100191

2. Peking University Center for Public Health and Epidemic Preparedness & Response, Beijing 100191, China

衰老(aging)多指生物发育成熟后,随着年龄增大,机体中分子、细胞、组织和器官损伤逐步累积,导致结构与功能发生渐进退行性改变的不可逆过程[1-2]。随着人类的预期寿命的延长和生育率的下降,我国人口老龄化问题愈发严重,2010年我国≥65岁人口占8.87%[3],而预计到2050年,这一比例将达到26.9%(4亿)[4]。2016年国务院印发《“健康中国2030”规划纲要》,提出全方位、全周期维护和保障人民健康,促进健康老龄化,这对个体与群体层面的抗衰老预防控制策略提出了更高要求。

个体衰老受遗传因素和环境暴露的共同影响,表现出复杂的分子生物学特征(如基因组失稳,端粒损耗,表观遗传学改变,蛋白质稳态丧失等[5]),是主要慢性病(包括心脑血管疾病、癌症、慢性阻塞性肺疾病、2型糖尿病、高血压等)发生发展的共有生物学基础[6]。这些特征本质上由遗传决定,但其中机制尚未完全明确。分析遗传因素在衰老中的作用,明确衰老相关机制,有助于定位相关信号通路,从而抵抗衰老,延长寿命。

近年来,随着“人类基因组计划”的完成,高通量遗传检测技术和相关算法的发展,以及在大规模人群中的运用,极大地促进了基于人群衰老的遗传学研究。其中,全基因组关联研究(genome-wide association studies,GWAS)通过全基因组的测序分析,可较为全面地分析单核苷酸多态性(single nucleotide polymorphism,SNP)与衰老表型间的关联,进而确定与衰老关联的遗传位点[7]。本文主要对衰老相关表型的GWAS展开综述。

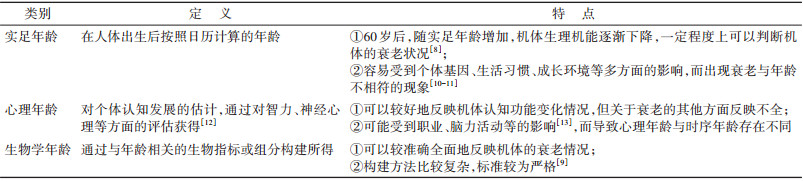

一、衰老表型的确定衰老是一种复杂的表型,目前较为常用的判定人体衰老的方法包括实足年龄(chronological age)、心理年龄(mental age)以及生物学年龄(biological age),三者定义、特点和内涵各不相同见表 1。

实足年龄是对人体衰老状况的直观判断,2015年WHO修订了年龄标准,定义25~44岁为青年时期,44~60岁为中年时期,≥60岁为老年时期,其中老年时期也被分为3个阶段:60~75岁是老年早期,此期间人类生理机能初步退化;76~90岁是老年中期,此期间人类的生理机能尤其是运动机能进一步退化;≥90岁为老年晚期(即长寿),此期间人类生理机能全面下降[3, 8]。

生物学年龄在准确判断个体衰老状况上具有明显优势,而衡量生物学年龄最重要的在于识别衰老相关的生物学标志物。为此,美国老龄化研究联合会提出了关于衰老生物标志物的标准[9]:可预测衰老速度;可反映衰老基本过程;可反复测试;适用于人和实验动物。目前除了端粒长度被认为是较弱的衰老生物学指标(预测性较差)外,几乎没有标志物或标志物组合可以满足所有标准[10]。本文主要选取寿命和端粒长度作为衰老表型展开综述。

二、人类寿命相关的GWAS研究[14-30]人的寿命受到遗传、环境暴露、生活方式、患病状态等多方面因素的综合影响[14-15]。现有关于寿命的GWAS多将“长寿”作为表型,定义为达到特定年龄限值[16],2015年WHO统一将活过90岁定义为长寿。人的寿命具有一定的遗传度,双生子研究中寿命遗传度范围为20%~30%,基于人群的关联研究中范围为15%~25%[16],而在对父母和子代的关联研究中遗传度约为12%[17],且随着年龄的增大,遗传因素对于“长寿”的影响越来越大[18]。

1. 长寿个体与年轻个体间的GWAS研究:通常长寿GWAS研究通过比较长寿个体和年轻个体之间遗传变异发生频率的差异,确定影响长寿的基因(表 2)。大多现有的GWAS表明长寿与载脂蛋白基因(ApoE)相关,ApoE蛋白有3个亚型(ApoEε2、ApoEε3和ApoEε4),不同表型与长寿间关联不同,如ApoEε4携带者罹患心血管疾病和阿尔茨海默病的风险增加,故ApoEε4相关的SNPs(如rs2075650、rs429358等)与长寿呈负相关;而ApoEε2携带者与相关疾病风险呈负相关,故ApoEε2相关的SNP(如rs7412)与长寿呈正相关[18-20]。此外,与参与细胞增殖调控的MINPP1基因相关的rs9664222[21],与炎性标记物相关的rs2069837等[22]位点均与长寿相关。

然而此种研究设计中也存在一定的问题,大部分长寿GWAS选择的对照是较为年轻的个体,对其是否死亡没有明确说明,若选择的是未死亡的年轻个体,其中也可能存在后续存活达到90岁及以上的个体,故从而使得研究对象分组错误,导致出现错误关联。

2. 父母长寿与子代基因型间的GWAS研究:长寿父母的后代可能继承了父母遗传变异的组合,而比短寿父母后代更健康且拥有更长的寿命[23]。相关GWAS将父母长寿作为表型,子代遗传变异作为基因型,探究影响长寿的相关基因位点(表 2)。Joshi等[24]验证了先前研究中的CHRNA3/5和ApoE基因上SNPs的关联,并发现了LPA和HLA-DQA1/DRB1基因上的关联,其中rs8042849位于CHRNA3/5(烟碱乙酰胆碱受体)基因上,该基因主要与吸烟有关[24],rs55730499(代理:rs10455872)位于LPA基因上,可能由于脂蛋白A和LDL-C水平及冠心病相关[25],而吸烟、冠心病等均与寿命之间存在很强的负相关[26]。Pilling等[23]的研究用了相同的方法,发现了rs429358(ApoE),rs1317286(CHRNA3/5),rs1556516(ANRIL)等10个与父母寿命相关的SNPs,及3个与母亲死亡年龄相关的SNPs和8个与父亲死亡年龄相关的SNPs。Timmers等[27]同样验证了ApoE、CHRNA3/5、LPA等基因上位点与长寿的关联。

此种研究采用Cox比例风险回归模型分析父母存活状态与子代基因型之间的关联,并不要求研究对象死亡,可以较为充分地利用数据。然而现有的父母长寿相关研究大多基于英国生物银行(UKB)或LifeGen队列进行,外部有效性有限。此外,由于子代的基因型由父母双方共同决定,在数据分析上需要特殊处理,比如所得效应值需要加倍等,对研究结果解读也需要考虑到父母双方的遗传影响。

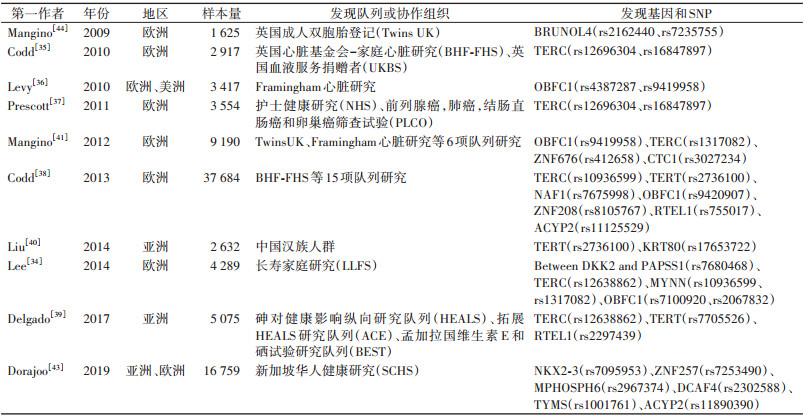

三、端粒长度的GWAS研究[31-44]端粒是位于核DNA两侧的重复核蛋白帽,其长度主要受到细胞复制和氧化的影响,一方面,随着有丝分裂期间核DNA的复制,端粒的长度逐渐缩短,平均每次分裂约丢失大约30~200个碱基对[31];另一方面,氧化应激可能引起的DNA单链断裂而导致端粒缩短,在端粒极短时,细胞将退出细胞周期并衰老[32],细胞衰老是机体衰老的重要机制。研究表明,随着年龄的增加,端粒的平均长度缩短[31],故常将端粒长度作为衰老替代指标。

现有关于端粒长度的GWAS研究大多将白细胞端粒长度(leukocyte telomere length,LTL)作为研究表型,其受遗传因素的影响较大,遗传度达到了80%[31]。既往研究提示,与具有较长LTL的个体相比,具有较短LTL的个体患有年龄相关疾病(例如心血管疾病、2型糖尿病、骨质疏松症、痴呆、癌症)和过早死亡的风险明显增加[33-34]。

LTL与端粒酶逆转录酶(TERT)、端粒酶RNA组分(TERC)、OBFC1等基因相关[35-38]。TERT和TERC基因与端粒酶的合成密切相关,在保护端粒完整性中起着重要的作用[39-40];OBFC1编码的蛋白是酵母Stn1的人类同源物,其可通过保护末端端粒DNA等维护端粒的长度[36, 41-42]。其他基因还包括MYNN基因[34]、ACYP2基因[43]等。

本文通过汇总既往GWAS研究,较为全面地梳理了与长寿表型及衰老代理表型(父母长寿、端粒长度)相关的遗传位点,例如ApoE、CHRNA3/5、LPA、TERT、TERC等多个基因,但其中可重复验证的位点较少。既往的GWAS研究在研究设计方面也存在一定局限:长寿组年龄界值不同(如≥80、≥90、≥100岁等),对照组多选择年轻的存活个体,且较常使用父母长寿、端粒长度等替代指标研究衰老。并且由于部分未达到全基因显著性水平的位点也可能对结局存在遗传效应或样本量有限,GWAS研究确定的关联位点仅能解释复杂性状遗传度的小部分;通过测序进行的GWAS研究一定程度上也依赖于基因分型芯片及遗传变异参考面板[7]。此外,现有的GWAS研究多来自于白种人,受人群分层影响,结果存在种族差异性;且受连锁不平衡的影响,研究得到的显著性位点不一定具有实际功能。未来可联合开展基于多种族、大样本、全生命周期随访的人群衰老GWAS研究,进一步探索和发现衰老相关遗传位点。

随着人类基因组计划的顺利进行,DNA数据库容量急剧扩增,表观遗传组学、蛋白组学、代谢组学等新兴学科发展迅速,也对衰老展开了进一步研究,如Horvath[45]、Hannum等[46]、Levine等[47]分别从多组织或血样中获得DNA甲基化信息,构建了多种表观遗传时钟,来探究DNA甲基化与衰老的关联。Menni等[48]和Hertel等[49]分别利用血液或尿液中的代谢物构建了代谢年龄,通过相关代谢物表征机体衰老变化。未来也可尝试开展基因组、表观遗传组、转录组、蛋白组、代谢组等多组学的人群研究,进一步系统地探索衰老的机制。

利益冲突 所有作者声明无利益冲突

| [1] |

Krištić J, Vučković F, Menni C, et al. Glycans are a novel biomarker of chronological and biological ages[J]. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci, 2014, 69(7): 779-789. DOI:10.1093/gerona/glt190 |

| [2] |

游庭活, 温露, 刘凡. 衰老机制及延缓衰老活性物质研究进展[J]. 天然产物研究与开发, 2015, 27(11): 1985-1990. You TH, Wen L, Liu F. Recent advances on active substances of anti-aging and its mechanisms[J]. Nat Prod Res Dev, 2015, 27(11): 1985-1990. DOI:10.16333/j.1001-6880.2015.11.026 |

| [3] |

Wang L, Li YH, Li HR, et al. Regional aging and longevity characteristics in China[J]. Arch Gerontol Geriatr, 2016, 67: 153-159. DOI:10.1016/j.archger.2016.08.002 |

| [4] |

Fang EF, Scheibye-Knudsen M, Jahn HJ, et al. A research agenda for aging in China in the 21 st century[J]. Ageing Res Rev, 2015, 24: 197-205. DOI:10.1016/j.arr.2015.08.003 |

| [5] |

López-Otín C, Blasco MA, Partridge L, et al. The hallmarks of aging[J]. Cell, 2013, 153(6): 1194-1217. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.039 |

| [6] |

Dodig S, Čepelak I, Pavić I. Hallmarks of senescence and aging[J]. Biochem Med (Zagreb), 2019, 29(3): 030501. DOI:10.11613/BM.2019.030501 |

| [7] |

Tam V, Patel N, Turcotte M, et al. Benefits and limitations of genome-wide association studies[J]. Nat Rev Genet, 2019, 20(8): 467-484. DOI:10.1038/s41576-019-0127-1 |

| [8] |

Dyussenbayev A. Age periods of human life[J]. Adv Soc Sci Res J, 2017, 4(6): 258-263. DOI:10.14738/assrj.46.2924 |

| [9] |

Bürkle A, Moreno-Villanueva M, Bernhard J, et al. MARK-AGE biomarkers of ageing[J]. Mech Ageing Dev, 2015, 151: 2-12. DOI:10.1016/j.mad.2015.03.006 |

| [10] |

Jylhävä J, Pedersen NL, Hägg S. Biological age predictors[J]. EBioMedicine, 2017, 21: 29‐36. DOI:10.1016/j.ebiom.2017.03.046 |

| [11] |

赵梦晗, 杨凡. 中国老年人的主观年龄及影响因素分析[J]. 人口学刊, 2020, 42(2): 41-53. Zhao MH, Yang F. Differences in the subjective age of Chinese older adults and its determinants[J]. Popul J, 2020, 42(2): 41-53. DOI:10.16405/j.cnki.1004-129X.2020.02.004 |

| [12] |

叶国萍. 智力理论及比奈量表发展述评[J]. 贵阳学院学报: 社会科学版, 2008, 3(31): 96-100. Ye GP. A review of the development of the intelligence theory and binet scale[J]. J Guiyang Univ: Soc Sci, 2008, 3(31): 96-100. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1673-6133.2008.01.023 |

| [13] |

马来记, 金锡鹏, 周彤, 等. 不同职业人群的生理年龄和心理年龄研究[J]. 中华劳动卫生职业病杂志, 2000, 18(3): 155-157. Ma LJ, Jin XP, Zhou T, et al. Effects of occupational classifications on physiological and psychological age[J]. Chin J Ind Hyg Occup Dis, 2000, 18(3): 155-157. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1001-9391.2000.03.009 |

| [14] |

Walter S, Atzmon G, Demerath EW, et al. A genome-wide association study of aging[J]. Neurobiol Aging, 2011, 32(11): 2109.e15-2109.e28. DOI:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.05.026 |

| [15] |

Broer L, Buchman AS, Deelen J, et al. GWAS of longevity in CHARGE consortium confirms APOE and FOXO3 candidacy[J]. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci, 2015, 70(1): 110-118. DOI:10.1093/gerona/glu166 |

| [16] |

Broer L, van Duijn CM. GWAS and meta-analysis in aging/longevity[M]//Atzmon G. Longevity genes. New York: Springer, 2015, 847: 107-125. DOI: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2404-2_5.

|

| [17] |

Deelen J, Evans DS, Arking DE, et al. A meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies identifies multiple longevity genes[J]. Nat Commun, 2019, 10(1): 3669. DOI:10.1038/s41467-019-11558-2 |

| [18] |

Nebel A, Kleindorp R, Caliebe A, et al. A genome-wide association study confirms APOE as the major gene influencing survival in long-lived individuals[J]. Mech Ageing Dev, 2011, 132(6/7): 324-330. DOI:10.1016/j.mad.2011.06.008 |

| [19] |

Deelen J, Beekman M, Uh HW, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies a single major locus contributing to survival into old age; the APOE locus revisited[J]. Aging Cell, 2011, 10(4): 686-698. DOI:10.1111/j.1474-9726.2011.00705.x |

| [20] |

Sebastiani P, Solovieff N, Dewan AT, et al. Genetic signatures of exceptional longevity in humans[J]. PLoS One, 2012, 7(1): e29848. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0029848 |

| [21] |

Newman AB, Walter S, Lunetta KL, et al. A meta-analysis of four genome-wide association studies of survival to age 90 years or older: the cohorts for heart and aging research in genomic epidemiology consortium[J]. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci, 2010, 65A(5): 478-487. DOI:10.1093/gerona/glq028 |

| [22] |

Zeng Y, Nie C, Min JX, et al. Novel loci and pathways significantly associated with longevity[J]. Sci Rep, 2016, 6: 21243. DOI:10.1038/srep21243 |

| [23] |

Pilling LC, Kuo CL, Sicinski K, et al. Human longevity: 25 genetic loci associated in 389 166 UK biobank participants[J]. Aging (Albany NY), 2017, 9(12): 2504-2520. DOI:10.18632/aging.101334 |

| [24] |

Joshi PK, Fischer K, Schraut KE, et al. Variants near CHRNA3/5 and APOE have age-and sex-related effects on human lifespan[J]. Nat Commun, 2016, 7: 11174. DOI:10.1038/ncomms11174 |

| [25] |

Clarke R, Peden JF, Hopewell JC, et al. Genetic variants associated with Lp(a) lipoprotein level and coronary disease[J]. N Engl J Med, 2009, 361(26): 2518-2528. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa0902604 |

| [26] |

Joshi PK, Pirastu N, Kentistou KA, et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis associates HLA-DQA1/DRB1 and LPA and lifestyle factors with human longevity[J]. Nat Commun, 2017, 8(1): 910. DOI:10.1038/s41467-017-00934-5 |

| [27] |

Timmers PRHJ, Mounier N, Lall K, et al. Genomics of 1 million parent lifespans implicates novel pathways and common diseases and distinguishes survival chances[J]. eLife, 2019, 8: e39856. DOI:10.7554/eLife.39856 |

| [28] |

Malovini A, Illario M, Iaccarino G, et al. Association study on long-living individuals from Southern Italy identifies rs10491334 in the CAMKIV gene that regulates survival proteins[J]. Rejuvenation Res, 2011, 14(3): 283-291. DOI:10.1089/rej.2010.1114 |

| [29] |

Flachsbart F, Caliebe A, Kleindorp R, et al. Association of FOXO3A variation with human longevity confirmed in German centenarians[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2009, 106(8): 2700-2705. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0809594106 |

| [30] |

Deelen J, Beekman M, Uh HW, et al. Genome-wide association meta-analysis of human longevity identifies a novel locus conferring survival beyond 90 years of age[J]. Hum Mol Genet, 2014, 23(16): 4420-4432. DOI:10.1093/hmg/ddu139 |

| [31] |

Gu J, Chen M, Shete S, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies a locus on chromosome 14q21 as a predictor of leukocyte telomere length and as a marker of susceptibility for bladder cancer[J]. Cancer Prev Res (Phila), 2011, 4(4): 514-521. DOI:10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0063 |

| [32] |

Sanders JL, Newman AB. Telomere length in epidemiology: a biomarker of aging, age-related disease, both, or neither?[J]. Epidemiol Rev, 2013, 35(1): 112-131. DOI:10.1093/epirev/mxs008 |

| [33] |

Saxena R, Bjonnes A, Prescott J, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies variants in casein kinase Ⅱ (CSNK2A2) to be associated with leukocyte telomere length in a Punjabi Sikh diabetic cohort[J]. Circ Cardiovasc Genet, 2014, 7(3): 287-295. DOI:10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.113.000412 |

| [34] |

Lee JH, Cheng R, Honig LS, et al. Genome wide association and linkage analyses identified three loci-4q25, 17q23.2, and 10q11.21-associated with variation in leukocyte telomere length: the long life family study[J]. Front Genet, 2014, 4: 310. DOI:10.3389/fgene.2013.00310 |

| [35] |

Codd V, Mangino M, van der Harst P, et al. Common variants near TERC are associated with mean telomere length[J]. Nat Genet, 2010, 42(3): 197-199. DOI:10.1038/ng.532 |

| [36] |

Levy D, Neuhausen SL, Hunt SC, et al. Genome-wide association identifies OBFC1 as a locus involved in human leukocyte telomere biology[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2010, 107(20): 9293-9298. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0911494107 |

| [37] |

Prescott J, Kraft P, Chasman DI, et al. Genome-wide association study of relative telomere length[J]. PLoS One, 2011, 6(5): e19635. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0019635 |

| [38] |

Codd V, Nelson CP, Albrecht E, et al. Identification of seven loci affecting mean telomere length and their association with disease[J]. Nat Genet, 2013, 45(4): 422-427. DOI:10.1038/ng.2528 |

| [39] |

Delgado DA, Zhang CN, Chen LS, et al. Genome-wide association study of telomere length among South Asians identifies a second RTEL1 association signal[J]. J Med Genet, 2018, 55(1): 64-71. DOI:10.1136/jmedgenet-2017-104922 |

| [40] |

Liu Y, Cao L, Li ZQ, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies a locus on TERT for mean telomere length in Han Chinese[J]. PLoS One, 2014, 9(1): e85043. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0085043 |

| [41] |

Mangino M, Hwang SJ, Spector TD, et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis points to CTC1 and ZNF676 as genes regulating telomere homeostasis in humans[J]. Hum Mol Genet, 2012, 21(24): 5385-5394. DOI:10.1093/hmg/dds382 |

| [42] |

Wan M, Qin J, Zhou SY, et al. OB Fold-Containing Protein 1 (OBFC1), a human homolog of yeast Stn1, associates with TPP1 and is implicated in telomere length regulation[J]. J Biol Chem, 2009, 284(39): 26725-26731. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M109.021105 |

| [43] |

Dorajoo R, Chang XL, Gurung RL, et al. Loci for human leukocyte telomere length in the Singaporean Chinese population and trans-ethnic genetic studies[J]. Nat Commun, 2019, 10(1): 2491. DOI:10.1038/s41467-019-10443-2 |

| [44] |

Mangino M, Richards JB, Soranzo N, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies a novel locus on chromosome 18q12.2 influencing white cell telomere length[J]. J Med Genet, 2009, 46(7): 451-454. DOI:10.1136/jmg.2008.064956 |

| [45] |

Horvath S. DNA methylation age of human tissues and cell types[J]. Genome Biol, 2013, 14(10): R115. DOI:10.1186/gb-2013-14-10-r115 |

| [46] |

Hannum G, Guinney J, Zhao L, et al. Genome-wide methylation profiles reveal quantitative views of human aging rates[J]. Mol Cell, 2013, 49(2): 359-367. DOI:10.1016/j.molcel.2012.10.016 |

| [47] |

Levine ME, Lu AT, Quach A, et al. An epigenetic biomarker of aging for lifespan and healthspan[J]. Aging (Albany NY), 2018, 10(4): 573-591. DOI:10.18632/aging.101414 |

| [48] |

Menni C, Kastenmüller G, Petersen AK, et al. Metabolomic markers reveal novel pathways of ageing and early development in human populations[J]. Int J Epidemiol, 2013, 42(4): 1111-1119. DOI:10.1093/ije/dyt094 |

| [49] |

Hertel J, Friedrich N, Wittfeld K, et al. Measuring biological age via metabonomics: the metabolic age score[J]. J Proteome Res, 2016, 15(2): 400-410. DOI:10.1021/acs.jproteome.5b00561 |

2022, Vol. 43

2022, Vol. 43