文章信息

- 杜敏, 景文展, 汪亚萍, 康良钰, 商伟静, 刘民, 刘珏.

- Du Min, Jing Wenzhan, Wang Yaping, Kang Liangyu, Shang Weijing, Liu Min, Liu Jue

- “一带一路”沿线国家登革热流行情况及变化趋势研究

- Epidemic situation and trend of dengue fever in Belt and Road countries

- 中华流行病学杂志, 2022, 43(7): 1066-1072

- Chinese Journal of Epidemiology, 2022, 43(7): 1066-1072

- http://dx.doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn112338-20220125-00072

-

文章历史

收稿日期: 2022-01-25

登革热作为被忽视的热带病和最常见的蚊媒传播疾病,已造成严重的全球疾病负担[1, 2]。WHO估计2000-2013年全球年均1亿例登革热感染病例[3]。过去10年间,世界多国出现登革热暴发疫情,如2019年尼泊尔暴发疫情[4]和2012-2015年中国暴发疫情[5]。登革病毒通过人-蚊-人循环传播,埃及伊蚊为主要媒介,白纹伊蚊为次要媒介[6]。伊蚊最初发现于热带和亚热带地区,但现在几乎遍布大陆[7]。许多复杂因素相互作用加速登革热暴发,包括气候[8, 9](降雨量、温度和湿度等)、交通、人口密度[9, 10]、极端贫困和卫生设施不足[11]等。接种疫苗被认为是控制传染病最有效的策略,2015年12月起,四价登革热疫苗CYD-TDV在20个国家的9~45岁的人群中授权使用[7,12]。模型估计,按照WHO推荐血清阳性者接种疫苗后,不同年龄组人群登革热发病率将有不同程度下降[13]。然而,目前还需要更多的临床试验来评估其安全性和有效性[14, 15, 16],登革热主要防控策略仍旧为病媒控制[7,17]。

我国领土纵跨温带、亚热带和热带地区,易于伊蚊孳生,近年来,“一带一路”倡议下外出务工、旅游及参与其他国际交流的人数增加。在这种情况下,登革热一旦输入,很可能在本地继发传播[18]。2015年宁文艳等[19]对我国2004-2013年的登革热疫情进行时空变化调查,发现2004-2013年,80%以上的输入病例来自东南亚地区,且通过线性回归发现,中国登革热发病率的对数值与国外输入性病例数有显著线性相关(r=0.669,P=0.035)。因此,分析“一带一路”合作区域最新登革热流行现状及变化趋势有利于为我国开展针对性的疾病监测与防控提供证据,降低登革热的跨境传播风险。

对象与方法1. 研究对象:截至2021年12月9日,“一带一路”官网显示与我国签署了共建“一带一路”合作文件的国家共145个[20]。登革热发病率数据来自2019年全球疾病负担研究(Global Burden of Diseases Study 2019,GBD2019)。GBD按性别、年龄、地区和国家量化不同时间内疾病造成的相对程度的健康损失[21]。GBD团队利用来自各国(地区)卫生部及WHO等官方网站、已发表的文献及调查报告等数据,通过贝叶斯回归模型调整年龄及性别等因素后,采用时空高斯过程回归及负二项回归模型估计发病率数据[22]。由于GBD2019登革热数据资料显示126个国家和地区[21],最终145个“一带一路”合作文件签订国家中93个国家纳入分析,其中在亚洲、非洲、大洋洲、南美洲、北美洲和欧洲的国家分别为22、43、10、6、11和1个(表 1)。本研究的开源数据库GBD2019采用上述方法估计数据,未包含人体及动物调查或实验等,研究不涉及医学伦理及知情同意。

2. 研究指标

(1)2019年登革热年龄标准化发病率(age-standardized incidence rate,ASR):2019年ASR定义为每10万人中登革热发病人数。

(2)2013-2019年ASR的年估计百分比变化(estimated annual percentage change,EAPC):对特定时间间隔内发病率趋势的一种概括和广泛使用的指标[23],2013-2019年登革热ASR每年升高或下降的百分比变化,通过对登革热ASR的自然对数进行回归线拟合计算获得。公式为y=α+βx+ε,其中y=ln(ASR),x=年。EAPC(95%CI)计算公式为100×(eβ-1)[23]。当EAPC值(95%CI)均 > 0时,ASR为上升趋势(否则为下降趋势)[23]。

3. 统计学分析:采用R 3.4.0软件进行数据分析及绘图包括计算2013-2019年登革热ASR的EAPC、绘制2019年登革热ASR地图、2013-2019年亚洲、欧洲、非洲、大洋洲、北美洲、南美洲国家发病率的EAPC前10名(由高到低排序)国家的EAPC(95%CI)。

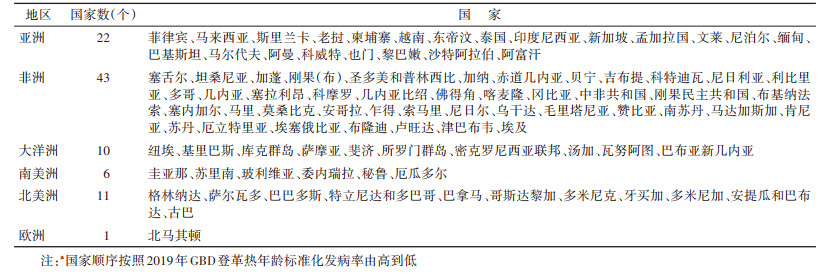

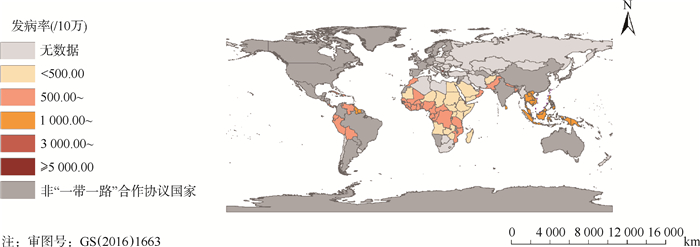

结果1. “一带一路”合作文件签署国家登革热流行现状:145个国家中93个国家有GBD登革热发病率数据,其中分别有5个(5.38%)、6个(6.45%)、16个(17.20%)、44个(47.31%)及22个(23.66%)国家登革热发病率为 > 5 000.00/10万、3 000.00~/10万、1 000.00~/10万、500.00~/10万及 < 500.00/10万。见图 1。5个发病率 > 5 000.00/10万的国家主要分布在大洋洲的3个国家,其次为非洲及欧洲各1个国家;6个发病率为3 000.00/10万~4 999.99/10万的国家均在大洋洲;16个发病率为1 000.00/10万~2 999.99/10万的国家主要在亚洲,占62.5%;44个发病率为500.00/10万~999.99/10万的国家主要在非洲,占56.82%,22个发病率为 < 500.00/10万的国家主要在非洲,占77.27%。

|

| 图 1 “一带一路”沿线国家2019年登革热流行现状 |

在22个亚洲国家中,10个(45.45%)国家发病率为1 000.00/10万~2 999.99/10万、7个(31.82%)国家发病率为500.00/10万~999.99/10万及5个(22.73%)国家发病率 < 500.00/10万。在43个非洲国家中,1个(2.33%)国家发病率 > 5 000.00/10万、25个(58.14%)国家发病率为500.00/10万~999.99/10万及17个(39.53%)国家发病率 < 500.00/10万。在10个大洋洲国家中,3个(30.00%)国家发病率 > 5 000.00/10万、6个(60.00%)国家发病率为3 000.00/10万~4 999.99/10万以及1个(10.00%)国家发病率为1 000.00/10万~2 999.99/10万。在北美洲共有11个国家有登革热流行,其中3个(27.27%)国家发病率为1 000.00/10万~2 999.99/10万及8个(72.73%)国家发病率为500.00/10万~999.99/10万。在6个南美洲国家中,分别有2个国家发病率为1 000.00/10万~2 999.99/10万及4个国家发病率为500.00/10万~999.99/10万。欧洲仅1个国家发病率 > 5 000.00/10万。

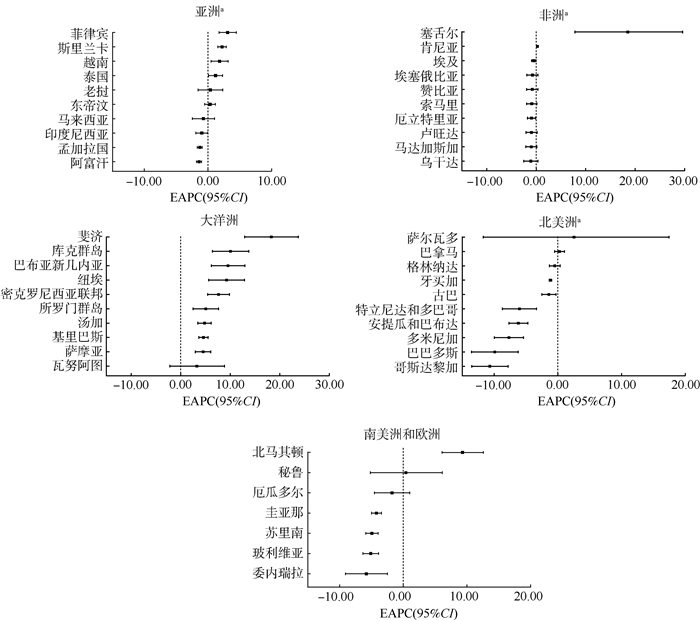

2. 2013-2019年“一带一路”沿线国家登革热发病率流行趋势:93个国家中,有16个国家登革热发病率呈上升趋势,其中大洋洲有9个国家(56.25%),亚洲有4个国家(25.00%),其余2个国家在非洲,1个国家在欧洲;58个国家登革热发病率呈下降趋势,剩余19个国家变化趋势不明显。见图 2。

|

| 注:a取EAPC值从高到低位居前10位的国家 图 2 2013-2019年“一带一路”沿线国家登革热发病率年估计百分比(EAPC)变化趋势 |

在亚洲22个国家中,分别有4个(18.18%)、4个(18.18%)和14个(63.64%)国家登革热发病率呈上升、无明显变化及下降趋势。菲律宾上升趋势最明显,登革热发病率年均增加百分比为3.09%(EAPC=3.09,95%CI:1.74~4.45),其次为斯里兰卡(EAPC=2.22,95%CI:1.55~2.89)、越南(EAPC=1.82,95%CI:0.48~3.18)及泰国(EAPC=1.19,95%CI:0.09~2.29)。在非洲43个国家中,分别有2个(4.65%)、9个(20.93%)及32个(74.42%)国家登革热发病率呈上升、无明显变化及下降趋势。塞舌尔上升趋势最明显,登革热发病率年均增加百分比为18.20%(EAPC=18.20,95%CI:7.82~29.58),其次为肯尼亚(EAPC=0.25,95%CI:0.10~0.39)。在大洋洲10个国家中,9个(90.00%)国家登革热发病率呈上升趋势,1个(10.00%)国家登革热发病率无明显变化。斐济上升趋势最明显,登革热发病率年均增加百分比为18.22%(EAPC=18.22,95%CI:12.91~23.77),其次为库克群岛(EAPC=10.01,95%CI:6.40~13.74)和巴布亚新几内亚(EAPC=9.53,95%CI:6.21~12.95)等国家。在北美洲11个国家中,3个(27.27%)国家登革热发病率变化趋势不明显,其余8个(72.73%)国家发病率均呈下降趋势。在南美洲6个国家中,2个国家登革热发病率变化趋势不明显,其余4个国家发病率均处于下降趋势。在欧洲国家中北马其顿的登革热发病率呈上升趋势(EAPC=9.27,95%CI:6.08~12.56)。

讨论截至2021年12月9日,“一带一路”官网显示合作协议签署国家共145个[20]。GBD2019登革热发病率数据显示其中93个国家有登革热流行,其中大洋洲国家发病率较高且多数国家发病率呈上升趋势,其次是亚洲、非洲及美洲,流行情况较轻。

本研究发现登革热主要流行区域在大洋洲,2019年登革热发病率 > 3 000.00/10万的国家共有11个,9个国家在大洋洲,且90%的国家发病率呈上升趋势。大洋洲包括较多分布在印度洋及太平洋周围的岛国。既往文献报道登革热所有4种血清型均在西太平洋区域流行[24]。近年,大洋洲多国已报告登革热流行。库克群岛2021年1-6月报道近300例登革热病例,国家采取综合措施包括加强病例监测、早期诊断、大量喷洒杀虫剂,加强日常垃圾收集、处理与管理、支持接种登革热疫苗,以便对流行地区的居民和来访的旅行者进行防控[25]。登革热传播主要依靠传播媒介包括白纹伊蚊和埃及伊蚊,传播媒介最初发现于热带和亚热带地区[7]。樊景春和刘起勇[26]报道白纹伊蚊分布于年平均温度高于11 ℃,年平均降水高于500 mm的区域;埃及伊蚊繁殖与雨季、平均温度高(24~33 ℃)、相对湿度大(80%~94%)等气候因素密切相关。大洋洲多个国家如纽埃、基里巴斯、库克群岛以及萨摩亚气候条件均适宜传播媒介繁衍[27]。除了适宜的气候外,包括交通、人口密度[9, 10]、极端贫困和卫生设施不足均可能是影响登革热暴发的重要因素[11]。

除大洋洲外,亚洲登革热流行现状较为严峻,2019年16个国家发病率为1 000.00/10万~2 999.99/10万,10个国家在亚洲,且18.18%的国家发病率呈上升趋势,并且菲律宾、斯里兰卡、泰国及越南等国家登革热流行呈上升趋势。亚洲登革热流行区域主要在东南亚地区,除文莱外,新加坡、马来西亚、印度尼西亚、缅甸、泰国、老挝、柬埔寨、越南和菲律宾近年来都报道了登革热疫情[28, 29]。2013-2017年菲律宾登革热发病率显著上升[30]。巴基斯坦人口最多的Karachi市和Lahore市每年都报告病例,2006-2017年Lahore市确诊病例超过1.7万例,降水量和平均最高气温是登革热流行的重要因素[31]。其他气象因素如风向、风力和气压可能有利于成年蚊虫延长存活时间并传播登革热[32]。飓风灾害等出现也与登革热发病率增加有关[33]。此外,城市住区人口密度高、缺乏公众认识以及有限的基础设施和资源可能进一步加速疫情暴发[34]。

我国领土幅员辽阔,与多个国家接壤,输入性疫情甚至可引发本土疫情暴发[35]。2006-2018年我国云南省瑞丽市共报告登革热病例3 022例,其中输入病例占59.13%(59.00%为境外输入)[36]。研究还发现输入病例年龄主要集中在16~45岁,来源于东南亚国家,尤其是缅甸[36]。我国云南省昆明市第三人民医院2018-2019年收治的191例登革热病例,东南亚地区输入约87.96%(柬埔寨占69.64%、缅甸占11.90%)[37]。除边境省份外,我国广东省、上海市也均报道输入性登革热疫情[38, 39]。此外,白纹伊蚊的抗药性、气候因素和东亚夏季季风也可能导致中国登革热发病率上升[40, 41, 42]。中国的“一带一路”倡议旨在促进全球和区域经济发展。项目开展过程中加强国际铁路、公路、航空、水路的互联互通等基础设施的建设,促进了国家间的人流量增加和人流速度显著增加[43]。与此同时,传播媒介的跨境传播以及传染源的流动增加提示应当注意在疾病流行季节以及重大项目开展期间,采取措施加强重点疾病的跨境传播管理。

目前,全球提倡实施病媒综合管理,包括创新型(自动捕蚊器、生物防治、网络平台早期预警)和传统的病媒控制措施结合以尽早通过降低蚊媒密度有效减轻登革热负担[17,44, 45, 46]。此外应规划城市化,加强基础设施和资源建设[44]。登革热高流行区域应鼓励人们参与蚊媒控制行动中,如使用蚊帐(特别是在清晨和傍晚前)、清理废弃轮胎和收集废水,使用经杀虫剂处理的蚊帐、屏风和墙壁[44]。输入性登革热疫情为主的国家,应加强旅行监测和管理,在登革热流行高峰期,当人们计划前往流行地区时,应告知登革热预防知识或尽可能接种疫苗[44]。

本研究存在局限性。数据来源于GBD2019,数据估计的准确性和稳健性取决于建模中使用的数据的质量和数量[23]。对于缺乏监测系统和人群研究的国家,登革热发病率估计值可能存在偏倚,部分国家缺少数据,无法分析登革热流行现状。

综上所述,2019年近60%的“一带一路”沿线国家有登革热流行,发病率数据显示大洋洲区域多数国家发病率较高,且处于上升趋势;其次登革热流行较重的区域依次为亚洲、非洲及美洲。研究结果提示在“一带一路”开展过程中,登革热流行区域国家应当促进多部门的协调合作,制定防控策略与措施,共同防止疾病传播。

利益冲突 所有作者声明无利益冲突

作者贡献声明 杜敏:资料收集、论文撰写、数据整理及统计分析;景文展:统计分析;汪亚萍、康良钰、商伟静:资料收集;刘珏、刘民:研究指导、论文修改及经费支持

| [1] |

Wilder-Smith A, Ooi EE, Horstick O, et al. Dengue[J]. Lancet, 2019, 393(10169): 350-363. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32560-1 |

| [2] |

Shepard DS, Undurraga EA, Halasa YA, et al. The global economic burden of dengue: a systematic analysis[J]. Lancet Infect Dis, 2016, 16(8): 935-941. DOI:10.1016/S1473-3099(16)00146-8 |

| [3] |

World Health Organization. Dengue and severe dengue[EB/OL]. (2021-12-29)[2022-01-05]. https://www.who.int/health-topics/dengue-and-severe-dengue#tab=tab_1.

|

| [4] |

Khadka S, Proshad R, Thapa A, et al. Wolbachia: a possible weapon for controlling dengue in Nepal[J]. Trop Med Health, 2020, 48: 50. DOI:10.1186/s41182-020-00237-4 |

| [5] |

Zhang H, Mehmood K, Chang YF, et al. Increase in cases of dengue in China, 2004-2016:A retrospective observational study[J]. Travel Med Infect Dis, 2020, 37: 101674. DOI:10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101674 |

| [6] |

Sim S, Hibberd ML. Genomic approaches for understanding dengue: insights from the virus, vector, and host[J]. Genome Biol, 2016, 17: 38. DOI:10.1186/s13059-016-0907-2 |

| [7] |

Otu A, Ebenso B, Etokidem A, et al. Dengue fever-an update review and implications for Nigeria, and similar countries[J]. Afr Health Sci, 2019, 19(2): 2000-2007. DOI:10.4314/ahs.v19i2.23 |

| [8] |

Wang WH, Chen HJ, Lin CY, et al. Imported dengue fever and climatic variation are important determinants facilitating dengue epidemics in Southern Taiwan[J]. J Infect, 2020, 80(1): 121-142. DOI:10.1016/j.jinf.2019.08.010 |

| [9] |

Mahmood S, Irshad A, Nasir JM, et al. Spatiotemporal analysis of dengue outbreaks in Samanabad town, Lahore metropolitan area, using geospatial techniques[J]. Environ Monit Assess, 2019, 191(2): 55. DOI:10.1007/s10661-018-7162-9 |

| [10] |

Costa SDSB, Branco MDRFC, Junior JA, et al. Spatial analysis of probable cases of dengue fever, chikungunya fever and zika virus infections in Maranhao State, Brazil[J]. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo, 2018, 60: e62. DOI:10.1590/S1678-9946201860062 |

| [11] |

da Conceição Araújo D, Dos Santos AD, Lima SVMA, et al. Determining the association between dengue and social inequality factors in north-eastern Brazil: A spatial modelling[J]. Geospat Health, 2020, 15(1): 854. DOI:10.4081/gh.2020.854 |

| [12] |

Freeman MC, Coyne CB, Green M, et al. Emerging arboviruses and implications for pediatric transplantation: A review[J]. Pediatr Transplant, 2019, 23(1): e13303. DOI:10.1111/petr.13303 |

| [13] |

Cattarino L, Rodriguez-Barraquer I, Imai N, et al. Mapping global variation in dengue transmission intensity[J]. Sci Transl Med, 2020, 12(528): eaax4144. DOI:10.1126/scitranslmed.aax4144 |

| [14] |

Wellekens K, Betrains A, de Munter P, et al. Dengue: current state one year before WHO 2010-2020 goals[J]. Acta Clin Belg, 2022, 77(2): 436-444. DOI:10.1080/17843286.2020.1837576 |

| [15] |

Lourenço J, Recker M. Dengue serotype immune-interactions and their consequences for vaccine impact predictions[J]. Epidemics, 2016, 16: 40-48. DOI:10.1016/j.epidem.2016.05.003 |

| [16] |

Robinson ML, Durbin AP. Dengue vaccines: implications for dengue control[J]. Curr Opin Infect Dis, 2017, 30(5): 449-454. DOI:10.1097/QCO.0000000000000394 |

| [17] |

Salazar F, Angeles J, Sy AK, et al. Efficacy of the In2Care® auto-dissemination device for reducing dengue transmission: study protocol for a parallel, two-armed cluster randomised trial in the Philippines[J]. Trials, 2019, 20(1): 269. DOI:10.1186/s13063-019-3376-6 |

| [18] |

汪圣强, 杨蒙蒙, 朱国鼎, 等. “一带一路”倡议下输入性蚊媒传染病的防控[J]. 中国血吸虫病防治杂志, 2018, 30(1): 9-13. Wang SQ, Yang MM, Zhu GD, et al. Control of imported mosquito-borne diseases under the Belt and Road Initiative[J]. Chin J Schisto Control, 2018, 30(1): 9-13. DOI:10.16250/j.32.1374.2017208 |

| [19] |

宁文艳, 鲁亮, 任红艳, 等. 2004-2013年间中国登革热疫情时空变化分析[J]. 地球信息科学学报, 2015, 17(5): 614-621. Ning WY, Lu L, Ren HY, et al. Spatial and temporal variations of dengue fever epidemics in China from 2004 to 2013[J]. J Geo-Inf Sci, 2015, 17(5): 614-621. DOI:10.3724/SP.J.1047.2015.00614 |

| [20] |

中国一带一路网. 已同中国签订共建“一带一路”合作文件的国家一览[EB/OL]. (2022-02-07)[2021-02-10]. https://www.yidaiyilu.gov.cn/xwzx/roll/77298.htm.

|

| [21] |

Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network. Global burden of disease study 2019(GBD 2019) Results[EB/OL]. (2019-12-09)[2021-12-10]. https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/.

|

| [22] |

GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019:a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019[J]. Lancet, 2020, 396(10258): 1204-1222. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9 |

| [23] |

Liu ZQ, Jiang YF, Yuan HB, et al. The trends in incidence of primary liver cancer caused by specific etiologies: Results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016 and implications for liver cancer prevention[J]. J Hepatol, 2019, 70(4): 674-683. DOI:10.1016/j.jhep.2018.12.001 |

| [24] |

Arima Y, Chiew M, Matsui T, et al. Epidemiological update on the dengue situation in the Western Pacific Region, 2012[J]. Western Pac Surveill Response J, 2015, 6(2): 82-89. DOI:10.5365/WPSAR.2014.5.4.002 |

| [25] |

Uwishema O, Nnagha EM, Chalhoub E, et al. Dengue fever outbreak in Cook Island: A rising concern, efforts, challenges, and future recommendations[J]. J Med Virol, 2021, 93(11): 6073-6076. DOI:10.1002/jmv.27223 |

| [26] |

樊景春, 刘起勇. 气候变化对登革热传播媒介影响研究进展[J]. 中华流行病学杂志, 2013, 34(7): 745-749. Fan JC, Liu QY. Research progress on the effect of climate change on dengue vector[J]. Chin J Epidemiol, 2013, 34(7): 745-749. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2013.07.020 |

| [27] |

Buchwald AG, Grover E, van Dyke J, et al. Human mobility associated with risk of Schistosoma japonicum infection in Sichuan, China[J]. Am J Epidemiol, 2021, 190(7): 1243-1252. DOI:10.1093/aje/kwaa292 |

| [28] |

Dyer O. Dengue: Philippines declares national epidemic as cases surge across South East Asia[J]. BMJ, 2019, 366: l5098. DOI:10.1136/bmj.l5098 |

| [29] |

Liang Y, Mohiddin MNA, Bahauddin R, et al. Modelling the effect of a novel autodissemination trap on the spread of Dengue in Shah Alam and Malaysia[J]. Comput Math Methods Med, 2019, 2019: 1923479. DOI:10.1155/2019/1923479 |

| [30] |

Xu ZW, Bambrick H, Yakob L, et al. High relative humidity might trigger the occurrence of the second seasonal peak of dengue in the Philippines[J]. Sci Total Environ, 2020, 708: 134849. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134849 |

| [31] |

Shabbir W, Pilz J, Naeem A. A spatial-temporal study for the spread of dengue depending on climate factors in Pakistan (2006-2017)[J]. BMC Public Health, 2020, 20(1): 995. DOI:10.1186/s12889-020-08846-8 |

| [32] |

Chumpu R, Khamsemanan N, Nattee C. The association between dengue incidences and provincial-level weather variables in Thailand from 2001 to 2014[J]. PLoS One, 2019, 14(12): e0226945. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0226945 |

| [33] |

Langkulsen U, Promsakha Na Sakolnakhon K, James N. Climate change and dengue risk in central region of Thailand[J]. Int J Environ Health Res, 2020, 30(3): 327-335. DOI:10.1080/09603123.2019.1599100 |

| [34] |

Pathak VK, Mohan M. A notorious vector-borne disease: Dengue fever, its evolution as public health threat[J]. J Family Med Prim Care, 2019, 8(10): 3125-3129. DOI:10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_716_19 |

| [35] |

曾小平, 陈琴, 王明昌, 等. 海口市2019年登革热本地和输入病例流行病学特征比较[J]. 中国热带医学, 2021, 21(8): 779-783. Zeng XP, Chen Q, Wang MC, et al. Comparison of epidemiological characteristics of local and imported cases of dengue fever in Haikou, 2019[J]. China Trop Med, 2021, 21(8): 779-783. DOI:10.13604/j.cnki.46-1064/r.2021.08.13 |

| [36] |

徐名芳, 岳玉娟, 刘小波, 等. 云南省瑞丽及景洪市2006-2018年登革热疫情特征比较研究[J]. 中国媒介生物学及控制杂志, 2021, 32(3): 318-323. Xu MF, Yue YJ, Liu XB, et al. Comparison of characteristics of dengue fever epidemic between Ruili and Jinghong, Yunnan province, China, 2006-2018[J]. Chin J Vect Biol Control, 2021, 32(3): 318-323. DOI:10.11853/j.issn.1003.8280.2021.03.012 |

| [37] |

刘冰, 黄瑛, 武彦, 等. 2018-2019年昆明市191例登革热患者临床特征分析[J]. 皮肤病与性病, 2021, 43(3): 325-327. Liu B, Huang Y, Wu Y, et al. Analysis of clinical characteristics of 191 cases of dengue fever in Kunming from 2018 to 2019[J]. J Dermatol Venereol, 2021, 43(3): 325-327. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1002-1310.2021.03.004 |

| [38] |

刘俊, 冯磊, 林晨, 等. 浦东新区输入性登革热病例流行病学与临床特征分析[J]. 中华卫生杀虫药械, 2021, 27(3): 258-260. Liu J, Feng L, Lin C, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of imported dengue fever in Pudong District[J]. Chin J Hyg Insect Equip, 2021, 27(3): 258-260. DOI:10.19821/j.1671-2781.2021.03.018 |

| [39] |

李海, 蔡明伟, 杨丽莉, 等. 2011-2020年广州市荔湾区登革热流行病学特征分析[J]. 医学动物防制, 2021, 37(9): 894-897. Li H, Cai MW, Yang LL, et al. Analysis on epidemiological characteristics of dengue fever in Liwan District of Guangzhou from 2011 to 2020[J]. J Med Pest Control, 2021, 37(9): 894-897. DOI:10.7629/yxdwfz202109022 |

| [40] |

Liu HM, Liu LH, Cheng P, et al. Bionomics and insecticide resistance of Aedes albopictus in Shandong, a high latitude and high-risk dengue transmission area in China[J]. Parasit Vectors, 2020, 13(1): 11. DOI:10.1186/s13071-020-3880-2 |

| [41] |

Li YJ, Zhou GF, Zhong DB, et al. Widespread multiple insecticide resistance in the major dengue vector Aedes albopictus in Hainan province, China[J]. Pest Manag Sci, 2021, 77(4): 1945-1953. DOI:10.1002/ps.6222 |

| [42] |

Liu KK, Hou X, Ren ZP, et al. Climate factors and the East Asian summer monsoon may drive large outbreaks of dengue in China[J]. Environ Res, 2020, 183: 109190. DOI:10.1016/j.envres.2020.109190 |

| [43] |

周兴武, 杨锐, 姜进勇, 等. 控制疟疾和登革热: 澜沧江-湄公河合作应对虫媒传染病挑战[J]. 中国病原生物学杂志, 2021, 16(1): 109-116. Zhou XW, Yang R, Jiang JY, et al. Lancang-Mekong collaboration in response to the challenge of vector-borne diseases: Control of malaria and dengue through Lancang-Mekong Cooperation[J]. J Parasit Biol, 2021, 16(1): 109-116. DOI:10.13350/j.cjpb.210124 |

| [44] |

Global strategy for dengue prevention and control 2012-2020[EB/OL]. Geneva: World Health Organization. (2022-01-29)[2022-03-21]. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/75303/1/9789241504034_eng.pdf.

|

| [45] |

Kamtchum-Tatuene J, Makepeace BL, Benjamin L, et al. The potential role of Wolbachia in controlling the transmission of emerging human arboviral infections[J]. Curr Opin Infect Dis, 2017, 30(1): 108-116. DOI:10.1097/QCO.0000000000000342 |

| [46] |

Li L, Liu WH, Zhang ZB, et al. The effectiveness of early start of Grade Ⅲ response to dengue in Guangzhou, China: A population-based interrupted time-series study[J]. PLoS Negl Trop Dis, 2020, 14(8): e0008541. DOI:10.1371/journal.pntd.0008541 |

2022, Vol. 43

2022, Vol. 43