文章信息

- 元玫雯, 王宏昊, 段如菲, 徐坤鹏, 胡尚英, 乔友林, 张勇, 赵方辉.

- Yuan Meiwen, Wang Honghao, Duan Rufei, Xu Kunpeng, Hu Shangying, Qiao Youlin, Zhang Yong, Zhao Fanghui

- 2016年中国归因于人乳头瘤病毒感染的肿瘤发病与死亡分析

- Analysis on cancer incidence and mortality attributed to human papillomavirus infection in China, 2016

- 中华流行病学杂志, 2022, 43(5): 702-708

- Chinese Journal of Epidemiology, 2022, 43(5): 702-708

- http://dx.doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn112338-20211010-00777

-

文章历史

收稿日期: 2021-10-10

2. 昆明医科大学第三附属医院/云南省肿瘤医院/云南省癌症中心妇科,昆明 650118;

3. 大连市第三人民医院质量管理部,大连 116044;

4. 中国医学科学院北京协和医学院,群医学及公共卫生学院全球健康中心,北京 100730

2. Department of Gynecology, The Third Affiliated Hospital of Kunming Medical University/Yunnan Cancer Hospital/Yunnan Cancer Center, Kunming 650118, China;

3. Department of Quality Management, Dalian No.3 People's Hospital, Dalian 116044, China;

4. Center for Global Health, School of Population Medicine and Public Health, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College, Beijing 100730, China

除宫颈癌外,高危型人乳头瘤病毒(HPV)持续感染还可以导致阴道、外阴、阴茎、肛门和头颈部位肿瘤[1],HPV疫苗可以有效预防宫颈及非宫颈部位病变的发生[2-4]。在WHO倡导全球消除宫颈癌的背景下,适龄女性进行HPV疫苗接种至关重要,我国制定适宜国情、经济而有效的接种策略需要全面评估HPV疫苗的经济学效益,因此亟需全面了解可归因于HPV感染的肿瘤发病和死亡数据。本研究利用全国肿瘤登记中心收集的2016年全国HPV相关肿瘤发病和死亡资料,分析我国2016年可归因于HPV感染的肿瘤发病和死亡情况,为HPV疫苗经济学效益的评估以及HPV相关疾病的防控策略制定提供基础数据。

资料与方法1. 资料来源:从国家癌症中心发布的《2019中国肿瘤登记年报》中获得2016年我国口腔癌(C02~06)、口咽癌(C01,C09~10)、喉癌(C32)、阴茎癌(C60)、阴道癌(C52)、宫颈癌(C53)、外阴癌(C51)、肛门癌(C21)分性别、地区和年龄的发病率和死亡率。从国家统计局公布的《中国人口和就业统计年鉴》中获得2016年全国分性别、分地区的各年龄组人口比例,结合2016年全国总人口数计算全国分性别、分地区的各年龄组人口数。

2. 统计学分析:发病率和死亡率乘以相应人口数得到HPV感染相关的肿瘤在不同性别、地区和年龄人群中的发病数和死亡数。因肛门癌、阴道癌、口腔癌、喉癌我国数据缺乏,使用国际人群归因分值(PAF)[5],而阴茎癌和口咽癌使用我国PAF[6-12]。根据PAF,得到归因于HPV感染的肿瘤在不同性别、地区和年龄人群中的发病数和死亡数。归因于HPV感染的发病数和死亡数除以相应人口数计算各年龄组归因于HPV感染肿瘤的粗发病率和粗死亡率,使用Segi's世界人口结构作为标准计算年龄标化发病率(ASIR)和年龄标化死亡率。数据整理、统计分析使用R 4.1.2软件。

结果1. 归因于HPV感染的肿瘤发病情况:2016年全国与HPV感染相关的肿瘤新发病例共178 540例,其中124 772例(69.89%)可归因于HPV感染,包括宫颈癌112 719例、女性非宫颈部位肿瘤4 399例,以及男性新发肿瘤7 654例(表 1)。在女性中,48.53%的新发肿瘤集中在45~59岁;其中51.52%的宫颈癌新发病例集中在40~54岁,以50~54岁最多;59.26%的非宫颈部位肿瘤新发病例发生在50~74岁,其中60~64岁最多。男性中,67.60%的新发肿瘤发生在50~74岁,其中60~64岁最多。

全国归因于HPV感染的肿瘤ASIR为6.32/10万,女性和男性分别为11.74/10万和0.75/10万。女性中,发病率排序依次为宫颈癌(11.32/10万)、肛门癌(0.14/10万)、阴道癌(0.12/10万)、外阴癌(0.06/10万)、口咽癌(0.06/10万)、口腔癌(0.03/10万)、喉癌(0.01/10万)。宫颈癌发病率随年龄增长呈快速上升趋势,在50~54岁达高峰(44.09/10万),之后大幅下降;非宫颈部位肿瘤发病率随年龄增长逐渐增加。男性中,发病率依次为阴茎癌(0.22/10万)、肛门癌(0.20/10万)、口咽癌(0.18/10万)、喉癌(0.10/10万)、口腔癌(0.06/10万),各部位肿瘤发病率随年龄增长呈上升趋势。女性和男性中皆为肛门癌随年龄增长发病率升高趋势最明显(图 1)。

|

| 图 1 2016年中国可归因于HPV感染的肿瘤发病率和发病人数 |

城市和农村各有67 683例和57 089例因HPV感染引起的肿瘤新发病例,农村地区肿瘤ASIR(6.50/10万)高于城市地区(5.99/10万),其中宫颈癌发病率(11.89/10万)高于城市地区(10.88/10万),而非宫颈部位肿瘤的ASIR城乡之间无较大差异(表 1)。

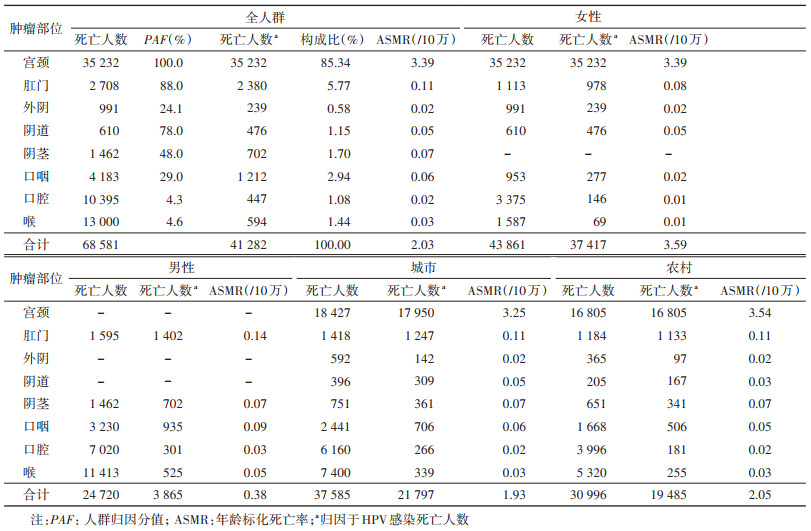

2. 归因于HPV感染的肿瘤死亡情况:全国有68 581例HPV感染相关的肿瘤死亡病例,其中41 282例(60.19%)归因于HPV感染,包括35 232例宫颈癌、女性非宫颈部位肿瘤2 185例和男性肿瘤3 865例(表 2)。女性中,53.45%的死亡病例发生在45~64岁;其中54.82%的宫颈癌死亡病例发生在45~64岁,50~54岁占比最重。74.32%的女性非宫颈部位肿瘤和72.78%的男性肿瘤死亡发生在60岁以后。

归因于HPV感染的肿瘤年龄标化死亡率为2.03/10万,女性和男性分别为3.59/10万和0.38/10万。女性中,不同部位肿瘤年龄标化死亡率依次为宫颈癌(3.39/10万)、肛门癌(0.08/10万)、阴道癌(0.05/10万)、外阴癌(0.02/10万)、口咽癌(0.02/10万)、口腔癌(0.01/10万)和喉癌(0.01/10万),其中阴道癌和口腔癌的死亡率随年龄增长持续上升,其他肿瘤死亡率总体呈上升趋势,在70岁后达到高峰;男性中,死亡率依次为肛门癌(0.14/10万)、口咽癌(0.09/10万)、阴茎癌(0.07/10万)、喉癌(0.05/10万)和口腔癌(0.03/10万),所有癌症的死亡率随年龄增长均呈上升趋势(图 2)。

|

| 图 2 2016年中国可归因于HPV感染的肿瘤死亡率和死亡人数 |

城市和农村各有21 797例和19 485例因HPV感染导致的肿瘤死亡病例,死亡率的差别与发病率相似,农村地区年龄标化死亡率(2.05/10万)略高于城市地区(1.93/10万),宫颈癌年龄标化死亡率农村地区(3.54/10万)高于城市地区(3.25/10万),非宫颈部位肿瘤的年龄标化死亡率城乡之间未见明显差异(表 2)。

讨论2016年我国归因于HPV感染的肿瘤发病124 772例,ASIR为6.32/10万,低于全球ASIR(8.00/10万),但发病人数约占全球发病人数的五分之一[5]。同时,与其他国家和地区相比,我国发病构成也有所不同。全球发病率前3位为宫颈癌、口咽癌和肛门癌[5],美国口咽癌居发病首位,其次是宫颈癌和肛门癌[13],我国发病率前3位是宫颈癌、阴茎癌和肛门癌。全球女性HPV相关肿瘤发病人数占发病总数的90.07%,在美国女性发病比例仅占56.33%,而我国该比例高达93.87%。发达国家新发病例和死亡病例中女性占比低可归因于大范围的宫颈癌筛查,癌前病变治疗得当造成的宫颈癌发病率大幅下降[14],而我国宫颈癌的防控起步较晚,仍面临较大挑战,其发病率和死亡率依旧呈上升趋势[15]。在全球消除宫颈癌的进程中,WHO呼吁15岁以下女性HPV疫苗接种覆盖率达到90%,女性在35岁和45岁接受筛查的覆盖率达到70%,但我国目前15岁以下的女性疫苗接种率不足1%[16],筛查覆盖率不足目标筛查率的一半[17]。同时,我国也存在医疗资源分配不均衡的问题。我国农村女性报告接受过宫颈癌筛查的比例低于城市女性[18],且农村部分筛查出癌前病变的女性未能接受进一步诊治[19]。因此,尽管农村和城市高危型HPV感染率接近[20],但农村地区总体肿瘤发病率及宫颈癌发病率和死亡率均高于城市地区。农村地区医疗资源可及性差、筛查机会少、诊断和治疗不及时的问题仍然存在,提示我国宫颈癌筛查体系和方法上仍需优化[21]。

肛门癌发病率在美国、法国、加拿大等高收入国家逐年上升[22],头颈部肿瘤发病率在年轻男性中迅速上升[23],外阴癌在世界范围内因为人口增长和老龄化发病率呈上升趋势[24]。尽管当前我国归因于HPV感染的非宫颈部位肿瘤发病率均低于发达国家[22, 24-26],但我国归因于HPV感染的生殖器肿瘤在过去10年间发病和死亡呈上升趋势[27]。在未来我国宫颈癌发病得到有效控制后,可能出现与发达国家相似趋势,即归因于HPV感染的非宫颈部位肿瘤负担逐渐凸显。目前非宫颈部位肿瘤尚无适宜高效的筛查方法,通过HPV疫苗接种可以预防非宫颈部位肿瘤发生——疫苗接种可以预防90%以上的高级别外阴或阴道病变、肛门上皮内瘤变、口咽鳞癌[2-4]。在美国、欧洲等国家和地区,九价HPV疫苗已经获批用于预防疫苗相关型别引起的肛门生殖器肿瘤[28-29]。同时美国还于2020年批准九价HPV疫苗用于预防头颈部肿瘤[28]。目前HPV疫苗在中国大陆地区获批的适应证只涉及宫颈部位,女性非宫颈部位肿瘤和男性肿瘤在将来如何防控有待解决。

对HPV疫苗的健康产出进行全面量化考察,规划经费投入力度、疫苗供应量和覆盖率时,研究者需要考虑其对非宫颈部位疾病的作用,从而确定HPV疫苗最优接种策略。而已有研究在评价HPV疫苗的效益时,仅考虑疫苗对宫颈癌的保护作用,忽视了疫苗对非宫颈部位肿瘤的效益。同时,观察HPV疫苗接种的人群效果,全面评估HPV疫苗接种的效益还需要归因于HPV的非宫颈部位肿瘤的HPV感染型别分布数据,而该部分数据仍待进一步补充。

本研究存在局限性。首先,由于我国部分非宫颈部位肿瘤HPV归因分值数据缺乏,故使用了国际PAF数值进行估算。其次,直肠癌和肛门癌的错分可能导致对肛门癌的低估。研究利用中国肿瘤登记年报中的肿瘤发病率和死亡率数据评估全国不同性别、年龄和地区归因于HPV感染的肿瘤发病和死亡现状,结果提供了基于人群的全国HPV相关肿瘤的发病与死亡情况,为归因于HPV感染肿瘤的防控及消除提供基础数据。

利益冲突 所有作者声明无利益冲突

作者贡献声明 元玫雯:数据分析、论文撰写;王宏昊:数据整理;段如菲:论文修改;徐坤鹏:统计学分析;胡尚英、乔友林:研究指导;张勇、赵方辉:研究指导、论文修改、经费支持

| [1] |

IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Biological agents. Volume 100 B. A review of human carcinogens[J]. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum, 2012, 100(Pt B): 1-441. |

| [2] |

Näsman A, Du J, Dalianis T. A global epidemic increase of an HPV-induced tonsil and tongue base cancer-potential benefit from a pan-gender use of HPV vaccine[J]. J Intern Med, 2020, 287(2): 134-152. DOI:10.1111/joim.13010 |

| [3] |

Palefsky JM, Giuliano AR, Goldstone S, et al. HPV vaccine against anal HPV infection and anal intraepithelial neoplasia[J]. N Engl J Med, 2011, 365(17): 1576-1585. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa1010971 |

| [4] |

Garland SM, Hernandez-Avila M, Wheeler CM, et al. Quadrivalent vaccine against human papillomavirus to prevent anogenital diseases[J]. N Engl J Med, 2007, 356(19): 1928-1943. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa061760 |

| [5] |

de Martel C, Georges D, Bray F, et al. Global burden of cancer attributable to infections in 2018:a worldwide incidence analysis[J]. Lancet Global Health, 2020, 8(2): e180-190. DOI:10.1016/s2214-109x(19)30488-7 |

| [6] |

侯炜, 马胜利, 赵旻, 等. 阴茎癌病因中人乳头瘤病毒和疱疹病毒Ⅱ型相关性研究[J]. 武汉大学学报: 医学版, 2002, 23(2): 125-127. Hou W, Ma SL, Zhao M, et al. Correlation of HPV and HSV-2 in the viral etiology of penis carcinomas[J]. Med J Wuhan Univ, 2002, 23(2): 125-127. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1671-8852.2002.02.010 |

| [7] |

翟建坡, 王其艳, 魏东, 等. 人乳头瘤病毒与阴茎癌预后的相关性[J]. 中华医学杂志, 2013, 93(34): 2719-2722. Zhai JP, Wang QY, Wei D, et al. Association between HPV DNA and disease specific survival in patients with penile cancer[J]. Nat Med J China, 2013, 93(34): 2719-2722. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0376-2491.2013.34.009 |

| [8] |

Gu WJ, Zhang PP, Zhang GM, et al. Importance of HPV in Chinese penile cancer: a contemporary multicenter study[J]. Front Oncol, 2020, 10: 1521. DOI:10.3389/fonc.2020.01521 |

| [9] |

杨苏梅, 吴蒙, 韩凤艳, 等. 49例口咽鳞癌与高危型HPV感染的关联分析[J]. 中华肿瘤防治杂志, 2020, 27(21): 1710-1717. Yang SM, Wu M, Han FY, et al. Correlation analysis of 49 cases of oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma and high-risk HPV infection[J]. Chin J Cancer Prev Threat, 2020, 27(21): 1710-1717. DOI:10.16073/j.cnki.cjcpt.2020.21.04 |

| [10] |

Lam EWH, Chan JYW, Chan ABW, et al. Prevalence, clinicopathological characteristics, and outcome of human papillomavirus-associated Oropharyngeal cancer in southern Chinese patients[J]. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 2016, 25(1): 165-173. DOI:10.1158/1055-9965.Epi-15-0869 |

| [11] |

王德林, 何士元, 乔天愚. 以HPV基因通用引物行PCR检测阴茎肿瘤组织中HPV.DNA[J]. 重庆医科大学学报, 2000, 25(1): 33-34, 32. Wang DL, He SY, Qiao TY. Detection of human papillomavirus (HPV) DNA in penile neoplasm by general primer mediated polymerase chain reaction[J]. Univ Sci Med Chongqing, 2000, 25(1): 33-34, 32. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.0253-3626.2000.01.011 |

| [12] |

庄奕宏. 阴茎癌患者血清可溶性肿瘤坏死因子受体水平与人乳头瘤病毒感染的研究[J]. 医师进修杂志, 2005, 28(20): 18-19, 44. Zhuang YH. The relationship between serum soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor level as well as human papillomavirus pathogen and penis carcinoma[J]. J Postgrad Med, 2005, 28(20): 18-19, 44. |

| [13] |

van Dyne EA, Henley SJ, Saraiya M, et al. Trends in human papillomavirus-associated cancers-United States, 1999- 2015[J]. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 2018, 67(33): 918-924. DOI:10.15585/mmwr.mm6733a2 |

| [14] |

Pierce Campbell CM, Menezes LJ, Paskett ED, et al. Prevention of invasive cervical cancer in the United States: past, present, and future[J]. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 2012, 21(9): 1402-1408. DOI:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-1158 |

| [15] |

Li XT, Zheng RS, Li XM, et al. Trends of incidence rate and age at diagnosis for cervical cancer in China, from 2000 to 2014[J]. Chin J Cancer Res, 2017, 29(6): 477-486. DOI:10.21147/j.issn.1000-9604.2017.06.02 |

| [16] |

刘捷宸, 吴琳琳, 白庆瑞, 等. 上海市2017-2019年人乳头瘤病毒疫苗接种率和疑似预防接种异常反应监测[J]. 中国疫苗和免疫, 2020, 26(3): 322-325, 348. Liu JC, Wu LL, Bai QR, et al. Surveillance for coverage of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine and adverse events following immunization with HPV vaccine in Shanghai, 2017-2019[J]. Chin J Vacc Immun, 2020, 26(3): 322-325, 348. |

| [17] |

张梅, 包鹤龄, 王丽敏, 等. 2015年中国宫颈癌筛查现况及相关因素分析[J]. 中华医学杂志, 2021, 101(24): 1869-1874. Zhang M, Bao HL, Wang LM, et al. Analysis of cervical cancer screening and related factors in China[J]. Natl Med J China, 2021, 101(24): 1869-1874. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.cn112137-20210108-00054 |

| [18] |

Wang BH, He MF, Chao AN, et al. Cervical cancer screening among adult women in China, 2010[J]. Oncologist, 2015, 20(6): 627-634. DOI:10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0303 |

| [19] |

Wang SX, Wu JL, Zheng RM, et al. A preliminary cervical cancer screening cascade for eight provinces rural Chinese women: a descriptive analysis of cervical cancer screening cases in a 3-stage framework[J]. Chin Med J, 2019, 132(15): 1773-1779. DOI:10.1097/cm9.0000000000000353 |

| [20] |

Zhao FH, Lewkowitz AK, Hu SY, et al. Prevalence of human papillomavirus and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia in China: a pooled analysis of 17 population-based studies[J]. Int J Cancer, 2012, 131(12): 2929-2938. DOI:10.1002/ijc.27571 |

| [21] |

Zhao FH, Qiao YL. Cervical cancer prevention in China: a key to cancer control[J]. Lancet, 2019, 393(10175): 969-970. DOI:10.1016/s0140-6736(18)32849-6 |

| [22] |

Islami F, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, et al. International trends in anal cancer incidence rates[J]. Int J Epidemiol, 2017, 46(3): 924-938. DOI:10.1093/ije/dyw276 |

| [23] |

Castellsagué X, Alemany L, Quer M, et al. HPV involvement in head and neck cancers: comprehensive assessment of biomarkers in 3 680 patients[J]. J Natl Cancer Inst, 2016, 108(6): djv403. DOI:10.1093/jnci/djv403 |

| [24] |

Bray F, Laversanne M, Weiderpass E, et al. Geographic and temporal variations in the incidence of vulvar and vaginal cancers[J]. Int J Cancer, 2020, 147(10): 2764-2771. DOI:10.1002/ijc.33055 |

| [25] |

de Martel C, Plummer M, Vignat J, et al. Worldwide burden of cancer attributable to HPV by site, country and HPV type[J]. Int J Cancer, 2017, 141(4): 664-670. DOI:10.1002/ijc.30716 |

| [26] |

Colberg C, van der Horst C, Jünemann KP, et al. Epidemiologie des Peniskarzinoms: epidemiology of penile cancer[J]. Urologe, 2018, 57(4): 408-412. DOI:10.1007/s00120-018-0593-7 |

| [27] |

Lu Y, Li PY, Luo GF, et al. Cancer attributable to human papillomavirus infection in China: burden and trends[J]. Cancer, 2020, 126(16): 3719-3732. DOI:10.1002/cncr.32986 |

| [28] |

Zhang Y, Fakhry C, D'Souza G. Projected Association of Human Papillomavirus Vaccination With Oropharynx Cancer Incidence in the US, 2020-2045[J]. JAMA Oncol, 2021, 7(10): e212907. DOI:10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.2907 |

| [29] |

Pathirana D, Hillemanns P, Petry KU, et al. Short version of the German evidence-based Guidelines for prophylactic vaccination against HPV-associated neoplasia[J]. Vaccine, 2009, 27(34): 4551-4559. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.03.086 |

2022, Vol. 43

2022, Vol. 43