文章信息

- 秦永发, 郭雁飞, 阮晔, 孙双圆, 黄哲宙, 吴凡.

- Qin Yongfa, Guo Yanfei, Ruan Ye, Sun Shuangyuan, Huang Zhezhou, Wu Fan

- 上海市50岁及以上居民膳食模式与认知功能的横断面研究

- Cross-sectional study of association between dietary pattern and cognitive performance in people aged 50 and above years in Shanghai

- 中华流行病学杂志, 2022, 43(5): 674-680

- Chinese Journal of Epidemiology, 2022, 43(5): 674-680

- http://dx.doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn112338-20210929-00758

-

文章历史

收稿日期: 2021-09-29

2. 上海市疾病预防控制中心, 上海 200336;

3. 复旦大学上海医学院, 上海 200032

2. Shanghai Municipal Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Shanghai 200336, China;

3. Shanghai Medical College, Fudan University, Shanghai 200032, China

认知功能指多维度的心理能力,包括学习、思考、推理、记忆等[1]。轻度认知功能受损是痴呆的前驱症状,每年有10%~15%的轻度认知功能受损者进展为痴呆[2]。膳食作为生活行为方式的一部分,其与认知功能的关联也得到了大量研究的证实[3-6]。然而,在不同人群中,提取的膳食模式及其与认知功能的关系并不一致[7]。例如在基于新加坡华人的一项前瞻性队列中发现中年时期坚持健康的饮食模式与晚年时期更低的认知功能受损风险相关,而在美国人群的一项前瞻性队列中发现中年时坚持健康的饮食模式与后期的痴呆发生风险无关[8-9];Yu等[10]在中国人群的一项横断面研究中,发现越倾向于“西方模式”者认知功能受损的风险越高,而Dearborn-Tomazos等[11]在美国的一项队列研究中发现中年时坚持“西方模式”与老年时的认知功能及痴呆风险无关。此外,有研究表明,以中国上海市为代表的长三角地区由于其独特的饮食文化和丰富的食物供给,而存在着特有的“江南饮食模式”[12]。目前尚无针对上海地区居民的膳食模式与认知功能关系的研究,本研究利用WHO全球老龄化与成人健康研究(Study of Global Ageing and Adult Health,SAGE)中国上海地区第二轮调查数据,提取上海市≥50岁居民的膳食模式并分析其与认知功能的关系。

对象与方法1. 研究对象:使用SAGE中国上海地区第二轮调查数据[13]。采取多阶段分层整群抽样的方法,共调查上海市4 808户家庭。考虑到家庭中个体的膳食摄入具有相似性,参照以往研究[14],从每个家庭中随机抽取≥50岁个体。纳入膳食数据完整、完成认知功能测试的个体,并排除有脑卒中病史者325人、基本信息及认知功能测试得分完全缺失者351人,最终纳入4 132人。

2. 研究方法:

(1)膳食模式:使用食物频率表调查对象过去3个月内111种食物的摄入频率(次/d,次/周,次/月,次/季)和每次的摄入量,个体油类和食盐的摄入为家庭月消费总量除以家庭人口数得到;根据营养特点将食物归为16大类:米面类、薯类、豆制品类、蔬菜类、水果类、乳类、蛋类、禽肉类、畜肉类、水产类、油类、食盐、白水、茶水、零食类、其他饮料;并计算出个体每日每类食物的总摄入量。采用因子分析法,将个体每日每类食物总摄入量纳入因子分析过程,计算KMO并进行Bartlett球形检验。利用主成分法提取公因子,进行最大方差旋转以便于解释[15]。综合特征根、碎石图、方差贡献率确定保留的公因子,根据因子中食物类别因子载荷和营养成分特点命名膳食模式。

(2)认知功能[1]:①语言流畅度:衡量从语义记忆中检索信息的能力。受访者在1 min内说出的正确动物名称的个数即此项测试得分。②词语回忆(3次即时测试和1次延时测试):衡量学习能力、记忆存储和记忆检索。调查人员读出10个单词后,让受访者重复,重复测试3次,10 min后再测试1次。此项测试总得分为4次测试的平均分。③数字测试(顺序和倒序):衡量工作记忆。调查员读出由短到长的数字串,让受访者重复,其所能重复的最长数字串长度即此项测试得分。参考SAGE相关研究,将各单项测试得分转化为z分数后相加计算出个体认知功能测试总分,得分越高认知功能越好[16]。

(3)变量定义:年龄、性别、身高、体重等基本信息均来自SAGE项目问卷。慢性病包括关节炎、心绞痛、糖尿病、慢性肺部疾病、哮喘、高血压、抑郁,调查员询问“您是否被医生诊断过患有(疾病)?”,通过受访者自报“是”“否”收集;吸烟状况分为:从未吸、目前不吸、目前吸;饮酒状况分为:从不饮、重度饮酒(过去7 d中,每日饮酒量为5个以上标准饮酒单位的日数≥4 d)、非重度饮酒;体力活动[17]:采用全球体力活动问卷作为测量工具,将体力活动水平分为低、中、高等级;BMI和中心性肥胖[18]:定义BMI < 18.5 kg/m2为低体重,18.5~kg/m2为正常体重,24.0~ kg/m2为超重,≥28.0 kg/m2为肥胖;男性腰臀比≥0.90,女性腰臀比≥0.85者定义为中心性肥胖。

(4)统计学分析:运用SPSS 22.0软件进行统计学分析。采用多重线性回归,调整性别、年龄、受教育年限、婚姻状况、退休、体力活动水平等因素后分析每种膳食模式因子得分与单项认知功能测试得分及认知功能测试总分的关系。并按性别、年龄、受教育年限、慢性病及退休进行分层分析以检验交互作用。双侧检验,检验水准α=0.05。

结果1. 膳食模式及其分布情况:因子分析KMO为0.78,Bartlett's球形检验P < 0.001,说明食物类别之间相关性较好,可做因子分析。综合碎石图、特征根、因子可解释性,保留3个公因子。方差贡献率分别为22.19%、10.16%、9.22%,累积贡献率41.57%。保留因子载荷 > 0.5的食物类别,根据其特点,命名3种模式为:植物性模式(豆制品类、蔬菜类、薯类和水果类因子载荷较大,分别为0.78、0.75、0.72、0.66);高动物食物模式(畜肉类、水产类、禽肉类因子载荷较大,分别为0.85、0.80、0.68);高油盐模式(油类和食盐因子载荷较大,分别为0.86、0.85)。

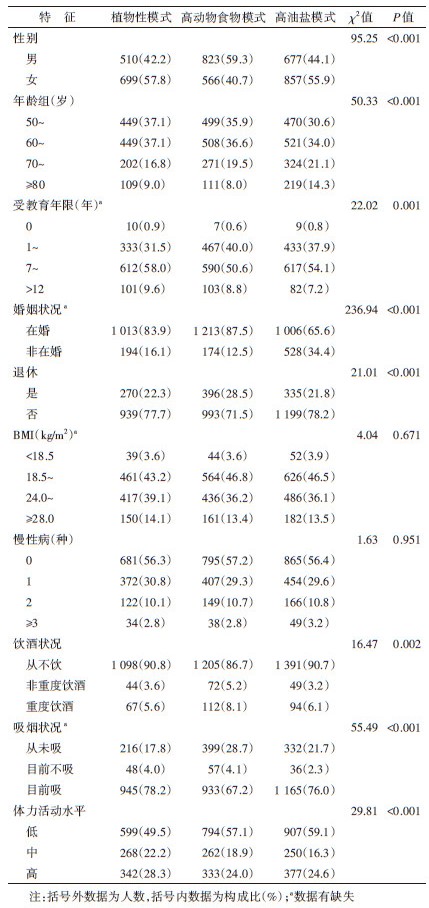

个体在某种膳食模式下因子得分越大,则越倾向该种膳食模式。研究对象中植物性模式者有1 209人,占29.3%;高动物食物模式者有1 389人,占33.6%;高油盐模式者1 534人,占37.1%。膳食模式在不同性别、年龄、受教育年限、婚姻状况、退休、饮酒状况、吸烟状况、体力活动水平中的分布差异有统计学意义(P < 0.05)(表 1)。

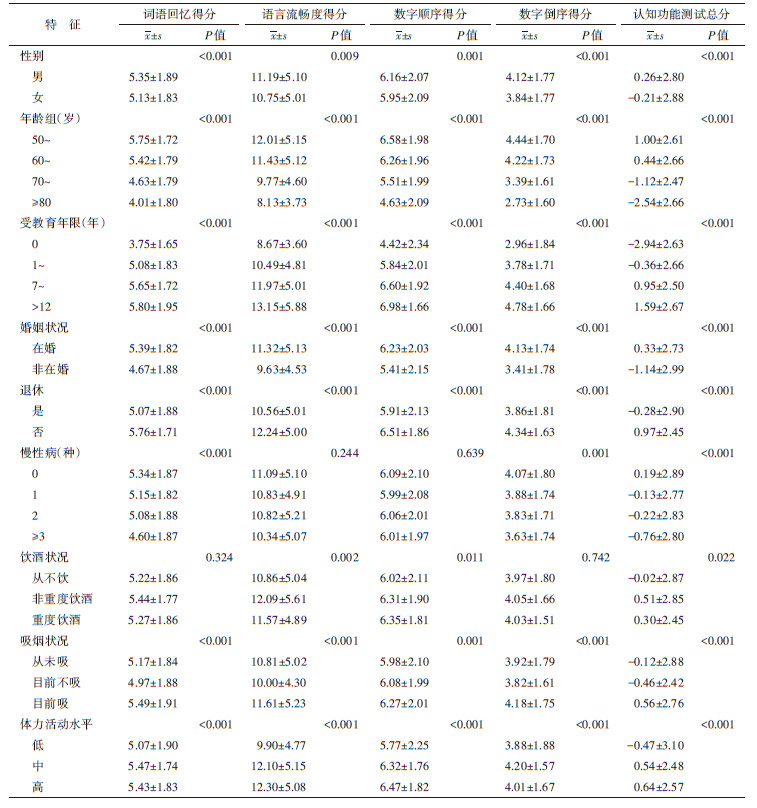

2. 认知功能测试得分情况:4项认知功能测试得分及认知功能测试总分在不同性别、年龄、受教育年限、婚姻状况、退休、慢性病、饮酒状况、吸烟状况及体力活动水平中的分布差异有统计学意义(P < 0.05)。男性、低年龄组、受教育年限长、在婚、未退休的各项认知功能测试得分和认知功能测试总分都更高(表 2)。

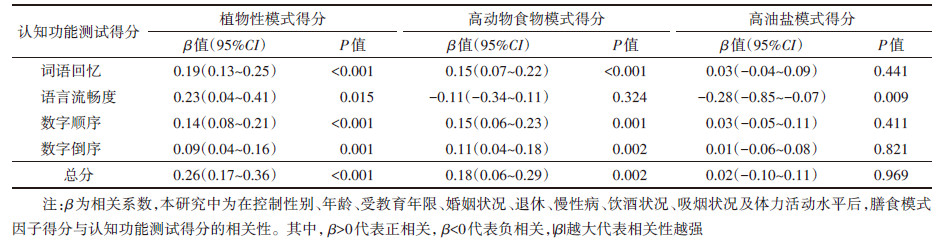

3. 不同膳食模式因子得分与认知测试得分的关联:以4项认知测试得分和认知测试总分为因变量,不同膳食模式下因子得分为自变量,校正潜在混杂因素后植物性模式得分与各单项认知测试得分及认知测试总分均正相关。其中,植物性模式得分每升高1分,认知测试总分增加0.26分(95%CI:0.17~0.36);高动物食物模式得分与词语回忆、数字顺序、数字倒序测试得分及认知测试总分正相关,高动物食物模式得分每升高1分,认知测试总分增加0.18分(95%CI:0.06~0.29);高油盐模式得分只与语言流畅度测试得分负相关(表 3)。

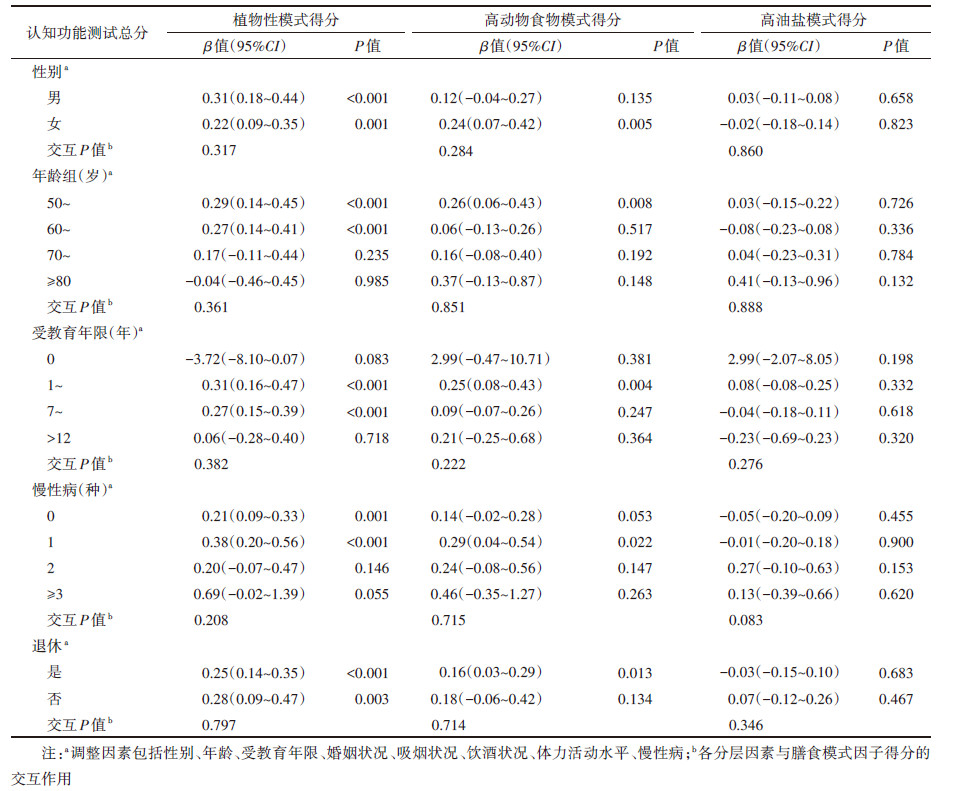

4. 亚组分析:按照性别、年龄、受教育年限、慢性病、退休进行分层分析,发现在不同性别及退休分组中,植物性模式和认知测试总分的关联与总体结果类似;而高动物食物模式与认知测试总分的关联只在部分组有统计学意义(P < 0.05);高油盐模式与认知测试总分的关联在各分层中均无统计学意义(P > 0.05)。膳食模式得分与各分层因素的交互作用也无统计学意义(P > 0.05)(表 4)。

本研究在上海市居民中提取了3种膳食模式:蔬菜类、豆制品类、薯类、水果类因子载荷较大的植物性模式;畜肉类、水产类、禽肉类因子载荷较大的高动物食物模式;油类和食盐因子载荷较大的高油盐模式。

植物性模式得分与各单项认知功能测试得分和认知功能测试总分正相关。该模式与著名的地中海膳食模式构成相似,而多数研究表明地中海膳食模式得分与认知功能正相关[19]。在美国人群中进行的一项队列研究中也命名了“植物性模式”,与更高的学习能力和记忆力测试得分相关[20]。基于法国人群的一项队列研究中提取的“健康模式”的个体在认知功能测试中有更好的表现[21]。在中国香港地区进行的一项横断面研究中提取了“蔬菜-水果模式”,与老年人更低的认知功能受损风险相关[22]。上述3种模式都富含蔬菜类、水果类、豆制品类等。可能的机制是蔬菜类、水果类食物含丰富的抗氧化、抗炎物质,因而具有神经细胞保护作用;蔬菜类、水果类、谷薯类含有丰富的膳食纤维,有益于肠道菌群的健康,从而维持更好的认知功能[23]。膳食纤维还能通过改善血脂、调节血糖等途径减少代谢综合征的发病风险,进而预防认知功能下降[24-25]。

高动物食物模式得分与个体的词语回忆、数字顺序、数字倒序得分和认知功能测试总分正相关。在以往的研究中,以动物性食物为主的膳食模式常与认知功能负相关或无明显关系[22, 26]。本研究结果与其不同,一方面可能是因为横断面的研究设计,如在魁北克营养与健康老龄化纵向研究中,基线时发现摄入肉类较多的“西方模式”与男性认知功能负相关,而在3年随访后发现在男性和女性中都未发现膳食模式与认知功能的关联[27];另一方面,基于后验法的膳食模式与认知功能关联的研究中,较少明确个体每种食物的具体摄入量,不同研究中食物组摄入量的差异可能也导致了最终的结果不同。然而,也有研究得出了与本研究相似的结论,如在中国台湾地区的一项队列研究中提取了“肉类模式”,其特点是大量摄入红肉、禽肉、烤肉。该模式与注意力下降负相关[28]。我国另一项横断面研究中命名的“MS”模式的特点是大量摄入红肉、禽肉、水产品、动物内脏,该模式与更好的整体认知功能相关[29]。在瑞典的一项队列研究中发现,摄入肉类及其制品与更高的认知功能得分相关[30]。本研究中高动物食物模式与更好的认知功能相关的可能机制是肉类、水产类中富含的锌是超氧化物歧化酶的组成成分,硒是谷胱甘肽还原酶的重要组分,二者都具有显著的抗氧化作用;神经元突触囊泡中的锌在学习和记忆功能等大脑活动中起着重要作用,锌的缺乏还与老年人频繁的感染发作、抑郁有关[31-32];红肉也是血红素铁的重要来源,红肉摄入不足可能与痴呆风险增加有关[33]。此外,肉类中富含的蛋白质和必需氨基酸(如色氨酸、酪氨酸)都对认知功能有益[34]。

高油盐模式与语言流畅度测试得分负相关。其可能的原因:首先,食盐摄入过多与神经毒性(淀粉样聚集体增加)有关,并影响全身血管和脑血管,导致血管性认知功能障碍及痴呆的发生。动物实验发现,食盐对认知功能的影响可能通过肠道调解途径发生,高钠饮食会导致小鼠的肠道适应性免疫反应,进而减少流向大脑的血液,并促进神经血管病变和认知功能障碍[35-36]。其次,高脂肪的饮食及肥胖会导致系统性炎症,进而导致大脑下丘脑区域的炎症,损伤认知功能[37]。

本研究从膳食模式的角度探讨了上海市居民饮食与认知功能的关系,与研究营养素或单一食物相比,其结果更具有公共卫生意义,能为开展健康宣教提供证据支持。但也存在不足:本研究剔除了部分数据缺失的样本,在一定程度上影响了结果外推,但缺失是随机的,且剔除个体与纳入个体的差异无统计学意义;其次,认知功能的危险因素众多,研究中虽然控制了年龄、受教育年限、婚姻状况以及慢性病等较为重要的因素,但因数据所限,仍有潜在因素未纳入分析,在后续研究中应充分考虑;最后,本研究为横断面设计,在因果关联判定上缺乏效力,研究结果应在进一步的队列数据中进行验证。

综上所述,多摄入植物性食物,适量摄入肉类的饮食模式可能与≥50岁居民更好的认知功能有关。

利益冲突 所有作者声明无利益冲突

作者贡献声明 秦永发:数据分析、论文撰写;阮晔、孙双圆、黄哲宙:数据整理、统计学分析;郭雁飞、吴凡:研究指导、论文修改、经费支持

| [1] |

Wu F, Guo YF, Zheng Y, et al. Social-economic status and cognitive performance among Chinese aged 50 years and older[J]. PLoS One, 2016, 11(11): e0166986. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0166986 |

| [2] |

Lombardi G, Crescioli G, Cavedo E, et al. Structural magnetic resonance imaging for the early diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease in people with mild cognitive impairment[J]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2020, 3(3): CD009628. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD009628.pub2 |

| [3] |

Cheung BHK, Ho ICH, Chan RSM, et al. Current evidence on dietary pattern and cognitive function[J]. Adv Food Nutr Res, 2014, 71: 137-163. DOI:10.1016/B978-0-12-800270-4.00004-3 |

| [4] |

Okubo H, Inagaki H, Gondo Y, et al. Association between dietary patterns and cognitive function among 70-year-old Japanese elderly: a cross-sectional analysis of the SONIC study[J]. Nutr J, 2017, 16(1): 56. DOI:10.1186/s12937-017-0273-2 |

| [5] |

Wesselman LMP, van Lent DM, Schröder A, et al. Dietary patterns are related to cognitive functioning in elderly enriched with individuals at increased risk for Alzheimer's disease[J]. Eur J Nutr, 2021, 60(2): 849-860. DOI:10.1007/s00394-020-02257-6 |

| [6] |

Corley J, Deary IJ. Dietary patterns and trajectories of global- and domain-specific cognitive decline in the Lothian Birth Cohort 1936[J]. Br J Nutr, 2021, 126(8): 1237-1246. DOI:10.1017/S0007114520005139 |

| [7] |

Solfrizzi V, Custodero C, Lozupone M, et al. Relationships of dietary patterns, foods, and micro- and macronutrients with Alzheimer's disease and late-life cognitive disorders: a systematic review[J]. J Alzheimers Dis, 2017, 59(3): 815-849. DOI:10.3233/JAD-170248 |

| [8] |

Wu J, Song XY, Chen GC, et al. Dietary pattern in midlife and cognitive impairment in late life: a prospective study in Chinese adults[J]. Am J Clin Nutr, 2019, 110(4): 912-920. DOI:10.1093/ajcn/nqz150 |

| [9] |

Hu EA, Wu AZ, Dearborn JL, et al. Adherence to dietary patterns and risk of incident dementia: findings from the atherosclerosis risk in communities study[J]. J Alzheimers Dis, 2020, 78(2): 827-835. DOI:10.3233/JAD-200392 |

| [10] |

Yu FN, Hu NQ, Huang XL, et al. Dietary patterns derived by factor analysis are associated with cognitive function among a middle-aged and elder Chinese population[J]. Psychiatry Res, 2018, 269: 640-645. DOI:10.1016/j.psychres.2018.09.004 |

| [11] |

Dearborn-Tomazos JL, Wu AZ, Steffen LM, et al. Association of dietary patterns in midlife and cognitive function in later Life in US adults without dementia[J]. JAMA Netw Open, 2019, 2(12): 1916641. DOI:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.16641 |

| [12] |

Wang JQ, Lin X, Bloomgarden ZT, et al. The Jiangnan diet, a healthy diet pattern for Chinese[J]. J Diabetes, 2020, 12(5): 365-371. DOI:10.1111/1753-0407.13015 |

| [13] |

郭雁飞, 施燕, 阮晔, 等. 全球老龄化与成人健康研究中国项目进展[J]. 中华流行病学杂志, 2019, 40(10): 1203-1205. Guo YF, Shi Y, Ruan Y, et al. Project profile: Study on global AGEing and adult health in China[J]. Chin J Epidemiol, 2019, 40(10): 1203-1205. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2019.10.006 |

| [14] |

Wang ZY, Zhao SL, Cui XY, et al. Effects of dietary patterns during pregnancy on preterm birth: a birth cohort study in Shanghai[J]. Nutrients, 2021, 13(7): 2367. DOI:10.3390/nu13072367 |

| [15] |

游杰, 袁亚群, 厉曙光, 等. 上海市成年居民膳食模式与肥胖的相关性研究[J]. 上海预防医学, 2016, 28(5): 294-299. You J, Yuan YQ, Li SG, et al. Study on identifying obesity related dietary patterns in Shanghai adults[J]. Shanghai J Prev Med, 2016, 28(5): 294-299. DOI:10.19428/j.cnki.sjpm.2016.05.004 |

| [16] |

Gildner TE, Liebert MA, Kowal P, et al. Associations between sleep duration, sleep quality, and cognitive test performance among older adults from six middle income countries: results from the study on global ageing and adult health (SAGE)[J]. J Clin Sleep Med, 2014, 10(6): 613-621. DOI:10.5664/jcsm.3782 |

| [17] |

World Health Organization. Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ) analysis guide[EB/OL]. [2021- 12-29]. https://www.who.int/ncds/surveillance/steps/resources/GPAQ_Analysis_Guide.pdf.

|

| [18] |

王琴, 王顺红, 王娜, 等. 上海市佘山镇65岁及以上老年人肥胖与血糖水平关联的横断面研究[J]. 上海预防医学, 2021, 33(6): 509-513. Wang Q, Wang SH, Wang N, et al. Cross-sectional study on the correlation between obesity and blood glucose level in elderly people over 65 years old in Sheshan town[J]. Shanghai J Prev Med, 2021, 33(6): 509-513. DOI:10.19428/j.cnki.sjpm.2021.19665 |

| [19] |

Singh B, Parsaik AK, Mielke MM, et al. Association of Mediterranean diet with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. J Alzheimers Dis, 2014, 39(2): 271-282. DOI:10.3233/JAD-130830 |

| [20] |

Pearson KE, Wadley VG, McClure LA, et al. Dietary patterns are associated with cognitive function in the reasons for geographic and racial differences in Stroke (REGARDS) cohort[J]. J Nutr Sci, 2016, 5: e38. DOI:10.1017/jns.2016.27 |

| [21] |

Kesse-Guyot E, Andreeva VA, Jeandel C, et al. A healthy dietary pattern at midlife is associated with subsequent cognitive performance[J]. J Nutr, 2012, 142(5): 909-915. DOI:10.3945/jn.111.156257 |

| [22] |

Chan R, Chan D, Woo J. A cross sectional study to examine the association between dietary patterns and cognitive impairment in older Chinese people in Hong Kong[J]. J Nutr Health Aging, 2013, 17(9): 757-765. DOI:10.1007/s12603-013-0348-5 |

| [23] |

Gehlich KH, Beller J, Lange-Asschenfeldt B, et al. Fruit and vegetable consumption is associated with improved mental and cognitive health in older adults from non- Western developing countries[J]. Public Health Nutr, 2019, 22(4): 689-696. DOI:10.1017/S1368980018002525 |

| [24] |

Yaffe K, Kanaya A, Lindquist K. The metabolic syndrome, inflammation, and risk of cognitive decline[J]. JAMA, 2004, 292(18): 2237-2242. DOI:10.1001/jama.292.18.2237 |

| [25] |

Raffaitin C, Féart C, Le Goff M, et al. Metabolic syndrome and cognitive decline in French elders: the Three-City Study[J]. Neurology, 2011, 76(6): 518-525. DOI:10.1212/WNL.0b013e31820b7656 |

| [26] |

Shakersain B, Santoni G, Larsson SC, et al. Prudent diet may attenuate the adverse effects of Western diet on cognitive decline[J]. Alzheimers Dement, 2016, 12(2): 100-109. DOI:10.1016/j.jalz.2015.08.002 |

| [27] |

D'Amico D, Parrott MD, Greenwood CE, et al. Sex differences in the relationship between dietary pattern adherence and cognitive function among older adults: findings from the NuAge study[J]. Nutr J, 2020, 19(1): 58. DOI:10.1186/s12937-020-00575-3 |

| [28] |

Chen YC, Jung CC, Chen JH, et al. Association of dietary patterns with global and domain-specific cognitive decline in Chinese elderly[J]. J Am Geriatr Soc, 2017, 65(6): 1159-1167. DOI:10.1111/jgs.14741 |

| [29] |

Yin ZX, Chen J, Zhang J, et al. Dietary patterns associated with cognitive function among the older people in underdeveloped regions: finding from the NCDFaC study[J]. Nutrients, 2018, 10(4): 464. DOI:10.3390/nu10040464 |

| [30] |

Titova OE, Ax E, Brooks SJ, et al. Mediterranean diet habits in older individuals: associations with cognitive functioning and brain volumes[J]. Exp Gerontol, 2013, 48(12): 1443-1448. DOI:10.1016/j.exger.2013.10.002 |

| [31] |

Berr C, Arnaud J, Akbaraly TN. Selenium and cognitive impairment: A brief-review based on results from the EVA study[J]. BioFactors, 2012, 38(2): 139-144. DOI:10.1002/biof.1003 |

| [32] |

Markiewicz-Żukowska R, Gutowska A, Borawska MH. Serum zinc concentrations correlate with mental and physical status of nursing home residents[J]. PLoS One, 2015, 10(1): e0117257. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0117257 |

| [33] |

Hooda J, Shah A, Zhang L. Heme, an essential nutrient from dietary proteins, critically impacts diverse physiological and pathological processes[J]. Nutrients, 2014, 6(3): 1080-1102. DOI:10.3390/nu6031080 |

| [34] |

van de Rest O, van der Zwaluw NL, de Groot LCPGM. Literature review on the role of dietary protein and amino acids in cognitive functioning and cognitive decline[J]. Amino Acids, 2013, 45(5): 1035-1045. DOI:10.1007/s00726-013-1583-0 |

| [35] |

Faraco G, Brea D, Garcia-Bonilla L, et al. Dietary salt promotes neurovascular and cognitive dysfunction through a gut-initiated TH17 response[J]. Nat Neurosci, 2018, 21(2): 240-249. DOI:10.1038/s41593-017-0059-z |

| [36] |

Taheri S, Yu J, Zhu H, et al. High-sodium diet has opposing effects on mean arterial blood pressure and cerebral perfusion in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer's disease[J]. J Alzheimers Dis, 2016, 54(3): 1061-1072. DOI:10.3233/JAD-160331 |

| [37] |

Tan BL, Norhaizan ME. Effect of high-fat diets on oxidative stress, cellular inflammatory response and cognitive function[J]. Nutrients, 2019, 11(11): 2579. DOI:10.3390/nu11112579 |

2022, Vol. 43

2022, Vol. 43