文章信息

- 戴宁彬, 朱晓燕, 姜来, 高艳, 华钰洁, 王临池, 周金意, 武鸣, 陆艳.

- Dai Ningbin, Zhu Xiaoyan, Jiang Lai, Gao Yan, Hua Yujie, Wang Linchi, Zhou Jinyi, Wu Ming, Lu Yan

- 苏州队列人群的胃癌发病状况及其危险因素

- Incidence of gastric cancer and risk factors in Suzhou cohort

- 中华流行病学杂志, 2022, 43(4): 452-459

- Chinese Journal of Epidemiology, 2022, 43(4): 452-459

- http://dx.doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn112338-20210707-00536

-

文章历史

收稿日期: 2021-07-07

2. 苏州市疾病预防控制中心慢性非传染病防制科, 苏州 215004;

3. 江苏省疾病预防控制中心慢性非传染病防制所, 南京 210009

2. Chronic Non-communicable Diseases Prevention and Control Department, Suzhou Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Suzhou 215004, China;

3. Chronic Non-communicable Diseases Prevention and Control Institute, Jiangsu Provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Nanjing 210009, China

恶性肿瘤是我国居民的首位死亡原因。统计数据显示,2015年胃癌已成为我国发病率第2位、死亡率第3位的癌症,疾病负担严重[1]。我国胃癌高发,这与我国居民的行为生活方式有着密切关系[2]。胃癌危险因素的研究很多,但基于我国自然人群队列的研究较少。本研究利用中国慢性病前瞻性研究(China Kadoorie Biobank,CKB)苏州队列描述胃癌发病率,分析相关危险因素。

对象与方法1. 研究对象:CKB于2004-2008年开展基线调查,随后进行长期随访,其研究设计详情参见文献[3-5]。本研究在CKB签署知情同意书并具有完整基线调查数据的53 260名苏州队列研究对象中剔除自报既往诊断消化性溃疡(2 809人)和恶性肿瘤(331人),入组半年内罹患胃癌(26人)者,去重后共50 136名研究对象纳入分析。

2. 胃癌发病评价:随访从研究对象完成基线调查之日起,直到出现胃癌发病、死亡、失访或至2013年12月31日止。胃癌发病和死亡信息通过苏州市慢性病监测系统、苏州市死因监测系统、全民医疗保险数据库以及主动定向监测等多途径获取,采用国际疾病分类第十版(ICD-10)对疾病进行分类,以随访期间出现胃部恶性肿瘤诊断(C16)作为结局。

3. 危险因素评价:基线调查时,由统一培训合格的调查员面对面开展问卷调查,收集研究对象的社会人口学特征(年龄、性别、文化程度、家庭年收入和婚姻状况)、行为生活方式(吸烟、饮酒、饮茶、饮食状况、体力活动和睡眠状况等)、健康状况(肿瘤家族史)和营养品摄入情况。身高和体重均采用统一校正的工具测量,BMI为体重与身高平方的比值。现在吸烟指目前大部分时间或每天都吸烟;已戒烟指现在不吸或偶尔吸,但曾经大部分时间或每天都吸;现在饮酒指目前至少每周饮酒一次;已戒酒指目前基本不饮酒,但以前曾经有过每周都喝且至少持续一年。本研究参考2011年版《体力活动概要》确定各项体力活动的能量代谢水平[6],以代谢当量(metabolic equivalent of task,MET)来反映活动强度,各项体力活动的属性及其MET赋值详见参考文献[7]。个体每天从事体力活动的水平(MET-h/d)为个体每天从事各类体力活动的MET值×从事该类体力活动的累计时间(h/d)的总和。

4. 统计学分析:采用Pearson χ2检验和趋势性χ2检验分析胃癌发病在分类变量和有序变量中的分布是否有差异,采用单因素Cox比例风险回归模型分析胃癌发生的潜在危险因素,差异有统计学意义的因素纳入多因素Cox比例风险回归模型,计算苏州地区胃癌危险因素的风险比(hazard ratio,HR)值及其95%CI,分析各危险因素与胃癌关联在不同性别中是否具有异质性,采用似然比检验分析是否存在相乘交互作用。所有统计学分析采用R 4.0.3软件,双侧检验,α=0.05。

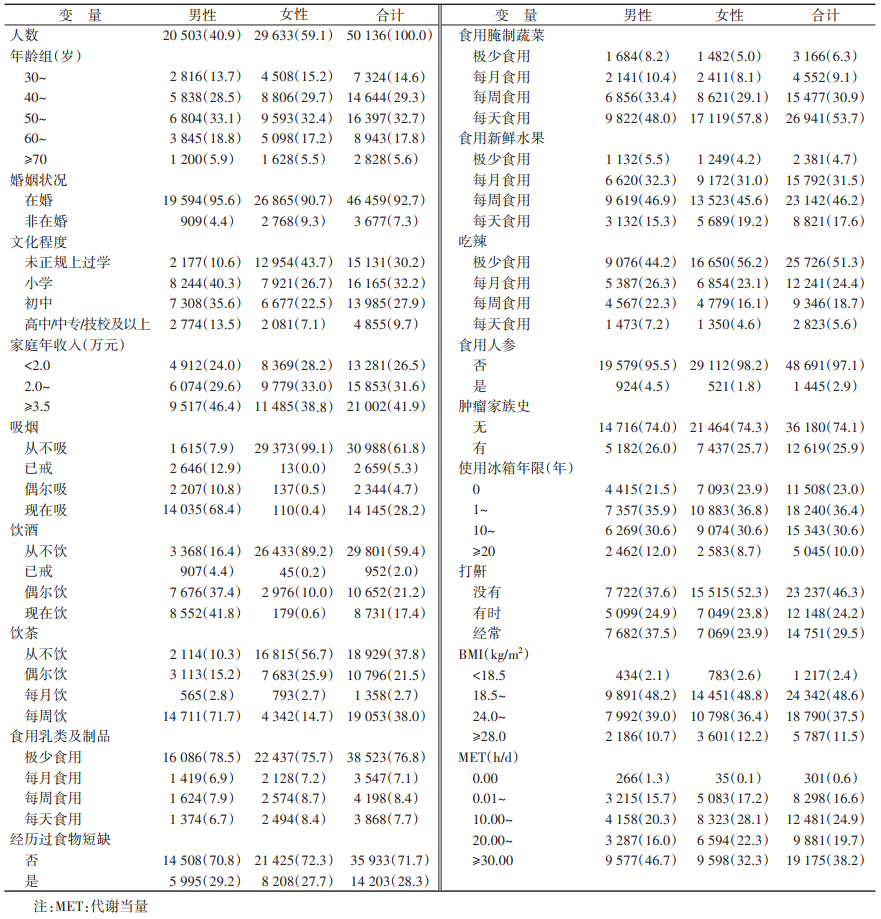

结果1. 基本情况:研究对象年龄为(51.48±10.36)岁,男性占40.9%。相比男性,未正规上过学、从不吸烟、从不饮酒、从不饮茶、每天食用腌制蔬菜、极少吃辣、不打鼾的女性比例较高,MET≥30.00 h/d的女性比例较低(表 1)。

2. 胃癌发病情况:研究对象中位随访时间为7.19年,共374人罹患胃癌,发病率为104.77/10万人年,标化发病率为94.57/10万人年(以2010年中国30~80岁人口数据标化)。其中,不同性别、年龄、婚姻状况、文化程度、家庭年收入、吸烟、饮酒、饮茶、食用乳类及制品、食用腌制蔬菜、食用新鲜水果、食用人参、吃辣、经历过食物短缺、有肿瘤家族史、使用冰箱年限、打鼾情况、BMI和MET的研究对象胃癌发生率差异有统计学意义(P < 0.05)。见表 2。

3. 胃癌发病危险因素:单因素Cox比例风险回归模型分析结果显示,年龄、非在婚、吸烟或已戒烟、现在饮酒或已戒酒、每周饮茶、每天或每周食用腌制蔬菜、经常打鼾、食用人参、经历过食物短缺和有肿瘤家族史会增加罹患胃癌的风险(P < 0.05),而女性、文化程度在初中及以上、家庭年收入高、食用新鲜水果、每月或每周吃辣、使用冰箱和体力活动多是胃癌发生的保护因素(P < 0.05)。见表 3。进一步多因素Cox比例风险回归模型分析结果显示,女性的胃癌发生风险低于男性(HR=0.44,95%CI:0.25~0.76,P=0.003),年龄每增长10岁胃癌发生风险是原先的2.20倍(95%CI:1.92~2.53,P < 0.001),现在吸烟人群胃癌发生风险是从不吸烟的1.84倍(95%CI:1.10~3.07,P=0.020),每周(HR=2.28,95%CI:1.28~4.07,P=0.005)和每天(HR=2.05,95%CI:1.16~3.61,P=0.013)食用腌制蔬菜均会增加胃癌发生风险,冰箱每多使用10年胃癌发生风险是原先的0.85倍(95%CI:0.74~0.97,P=0.016)。见表 3。

4. 性别在各危险因素与胃癌发生关联中的效应修饰作用:按性别分层分析发现,每周(HR=2.77,95%CI:1.39~5.54,P=0.004)和每天(HR=2.28,95%CI:1.15~4.50,P=0.018)食用腌制蔬菜、有肿瘤家族史(HR=1.38,95%CI:1.06~1.81,P=0.017)是男性胃癌的危险因素,但女性中未见统计学关联(P > 0.05),进一步异质性分析发现,上述3者与胃癌的关联在男女性中无统计学意义。男性中冰箱使用年限与胃癌无统计学关联(P=0.533),女性中冰箱使用年限是胃癌发生的保护因素(HR=0.61,95%CI:0.46~0.82,P < 0.001),且异质性检验发现冰箱使用年限与胃癌的关联在男女性中的差异有统计学意义(P=0.009)。见表 4。交互作用分析结果显示,同一性别中冰箱使用10~19年胃癌发生风险比最低,同一冰箱使用年限女性的胃癌发生风险较男性低,且随着冰箱使用年限的增加,男女性的胃癌发生风险差异逐渐增大。交互作用分析发现,性别与冰箱使用年限与胃癌发病的关联中存在交互作用(P=0.010)。见表 5。

本研究自2004年起对苏州市50 136名研究对象中位随访7.19年观察胃癌发病情况,胃癌标化人年发病率为94.57/10万人年,高于2012年苏州市30~80岁人群胃癌登记标化发病率(51.12/10万人,未发表)。由于CKB与我国肿瘤登记在整体研究设计、人群年龄结构及计算方法上存在异质性,因此两者的比较仅供参考。此外,CKB在招募参与者时产生的选择偏倚或样本的不具代表性亦可造成两者存在差异[8]。

研究发现年龄和男性是胃癌发病的危险因素,与既往各研究结果相同[9-10]。本研究发现只有现在吸烟才与胃癌发病有关,这与Karimi等[11]的研究和英国肿瘤研究项目的结果一致[12]。Praud等[13]发现胃癌发生风险随吸烟支数和年数的增加而增加。然而,Smyth等[14]的一项回顾性研究未发现吸烟与胃癌发病存在剂量-反应关系。吸烟与胃癌发病的关联及其效应大小有待更细致的研究。遗传学研究提示GSTT1、SULT1A1、CYP1a1和NAT2基因的多态性介导了吸烟与胃癌之间的个体易感性[15-17]。此外,吸烟胃癌患者CDH1基因的甲基化水平高于非吸烟者[18]。Rota等[19]分析“Stomach cancer Pooling Project”时发现整体看饮酒与胃癌发病没有统计学关联,但每天4次以上的重度饮酒与胃癌发病显著相关,Wang等[20]亦发现饮酒与胃癌发病存在非线性关联,重度饮酒的关联性强。而本研究单因素分析时已戒酒和现在饮酒均会增加胃癌发病风险,但多因素分析未发现饮酒与胃癌发病存在关联,可能原因是本研究饮酒状况仅区分是否饮酒,未区分不同饮酒程度。

本研究发现,每周或更高频率食用腌制蔬菜会增加胃癌发病风险,而食用新鲜蔬菜、新鲜水果和吃辣均与胃癌发病无关。Ren等[21]在韩国和中国人群中进行Meta分析发现,食用腌制蔬菜会增加50%的胃癌发病风险,与本研究结果一致。研究显示,盐会增加亚硝基化合物的形成,从而增强胃部致癌物质的作用,加剧幽门螺杆菌(Helicobacter pylori)的感染[22]。本研究对象中99.4%每天都食用新鲜蔬菜是导致研究未发现食用新鲜蔬菜与胃癌发病有关的原因之一。有假说认为,蔬菜和水果对胃癌的保护作用存在阈值。当大多数人蔬菜和水果的摄入量超过该阈值后,人群中就不会观察到其对胃癌的保护作用[23]。日本的一项队列研究发现食用新鲜水果与胃癌发生风险无关[24],与本研究结果相似。然而,Fang等[25]对76个队列研究分析发现,食用水果和白色蔬菜与胃癌发生风险有负向关联,新鲜蔬菜和水果与胃癌发生风险的关联有待进一步研究探讨。本研究人群食用乳类及制品与新鲜水果的频率显著相关,为防止共线性对结果产生影响,多因素分析时仅纳入了新鲜水果食用频率。众所周知,胃癌是遗传和环境因素共同作用导致的复杂性疾病。有研究发现胃癌发生过程中环境因素的作用大于遗传作用[26],这可能是肿瘤家族史在单因素分析时是胃癌危险因素而在多因素分析时未见显著关联的原因。

本研究结果显示,使用冰箱越久,胃癌的发病风险越低。Lin等[27]进行一项病例-对照研究时亦发现冰箱使用与胃癌发病负相关,并建议在胃癌高发的发展中国家推行使用冰箱以降低胃癌发病率。Park等[28]的一项生态学研究则发现使用冰箱与胃癌死亡负相关。Yan等[29]对12项研究进行Meta分析发现在亚洲地区使用冰箱是胃癌的保护因素,但在德国等西方国家中未发现两者有统计学关联。冰箱可使蔬菜保鲜时间更长,减少亚硝酸盐的产生,使维生素等抗氧化剂保持在较高水平,从而降低人体接触亚硝酸盐等致癌物的量[29-30]。冰箱的使用还可减少腌制和熏制等传统食物保存方法的使用,从而降低胃癌发病风险[31-32]。进一步分析发现,性别与冰箱使用存在协同交互作用:女性、使用冰箱越久发生胃癌的风险越小,其机制有待进一步研究确认。

本研究对胃癌高发苏州地区大样本人群进行了前瞻性队列研究,全面、定量探索了胃癌各危险因素及其效应大小,但仍存在一些不足。本研究未采集研究对象的幽门螺杆菌信息,可能损失了部分对胃癌危险因素的解释;饮食等信息由研究对象口述,可能存在回忆偏倚和无差异错分,使结果趋于无效假设;研究仅有基线信息,无法分析随访期间危险因素的变化与胃癌发生风险的关系。

综上,本研究发现年龄、现在吸烟、每周或更高频率食用腌制蔬菜是胃癌的危险因素,女性和使用冰箱是胃癌的保护因素,性别与使用冰箱在对胃癌发病的关联中存在协同交互作用。

利益冲突 所有作者声明无利益冲突

作者贡献声明 戴宁彬:统计学分析、论文撰写;朱晓燕、姜来、高艳:解释数据,技术支持;华钰洁、王临池:采集和整理数据;周金意、武鸣:对文章的知识性内容作批评性审阅;陆艳:研究设计、论文修改

志谢 感谢项目管理委员会、国家项目办公室、牛津协作中心和江苏省项目地区办公室的工作人员

| [1] |

孙可欣, 郑荣寿, 张思维, 等. 2015年中国分地区恶性肿瘤发病和死亡分析[J]. 中国肿瘤, 2019, 28(1): 1-11. Sun KX, Zheng RS, Zhang SW, et al. Report of cancer incidence and mortality in different areas of China, 2015[J]. China Cancer, 2019, 28(1): 1-11. DOI:10.11735/j.issn.1004-0242.2019.01.A001 |

| [2] |

Chen P, Lin YL, Zheng KC, et al. Risk factors of gastric cancer in high-risk region of China: a population-based case-control study[J]. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev, 2019, 20(3): 775-781. DOI:10.31557/APJCP.2019.20.3.775 |

| [3] |

李立明, 吕筠, 郭彧, 等. 中国慢性病前瞻性研究: 研究方法和调查对象的基线特征[J]. 中华流行病学杂志, 2012, 33(3): 249-255. Li LM, Lv J, Guo Y, et al. The China Kadoorie Biobank: related methodology and baseline characteristics of the participants[J]. Chin J Epidemiol, 2012, 33(3): 249-255. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2012.03.001 |

| [4] |

Chen ZM, Chen JS, Collins R, et al. China Kadoorie Biobank of 0.5 million people: survey methods, baseline characteristics and long-term follow-up[J]. Int J Epidemiol, 2011, 40(6): 1652-1666. DOI:10.1093/ije/dyr120 |

| [5] |

Chen ZM, Lee L, Chen JS, et al. Cohort profile: the Kadoorie study of chronic disease in China (KSCDC)[J]. Int J Epidemiol, 2005, 34(6): 1243-1249. DOI:10.1093/ije/dyi174 |

| [6] |

Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Herrmann SD, et al. 2011 Compendium of physical activities: a second update of codes and MET values[J]. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 2011, 43(8): 1575-1581. DOI:10.1249/MSS.0b013e31821ece12 |

| [7] |

Du HD, Bennett D, Li LM, et al. Physical activity and sedentary leisure time and their associations with BMI, waist circumference, and percentage body fat in 0.5 million adults: the China Kadoorie Biobank study[J]. Am J Clin Nutr, 2013, 97(3): 487-496. DOI:10.3945/ajcn.112.046854 |

| [8] |

潘睿. 中国慢性病前瞻性研究队列恶性肿瘤发病与死亡分析[D]. 南京: 南京医科大学, 2017. Pan R. Cancer incidence and mortality: a cohort study in China[D]. Nanjing: Nanjing Medical University, 2017. |

| [9] |

Marqués-Lespier JM, González-Pons M, Cruz-Correa M. Current perspectives on gastric cancer[J]. Gastroenterol Clin North Am, 2016, 45(3): 413-428. DOI:10.1016/j.gtc.2016.04.002 |

| [10] |

Machlowska J, Baj J, Sitarz M, et al. Gastric cancer: epidemiology, risk factors, classification, genomic characteristics and treatment strategies[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2020, 21(11): 4012. DOI:10.3390/ijms21114012 |

| [11] |

Karimi P, Islami F, Anandasabapathy S, et al. Gastric cancer: descriptive epidemiology, risk factors, screening, and prevention[J]. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 2014, 23(5): 700-713. DOI:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-1057 |

| [12] |

Cancer Research UK. 2015 Stomach cancer risk factors[EB/OL]. [2021-07-03]. http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/stomach-cancer/risk-factors.

|

| [13] |

Praud D, Rota M, Pelucchi C, et al. Cigarette smoking and gastric cancer in the stomach cancer pooling (StoP) project[J]. Eur J Cancer Prev, 2018, 27(2): 124-133. DOI:10.1097/CEJ.0000000000000290 |

| [14] |

Smyth EC, Capanu M, Janjigian YY, et al. Tobacco use is associated with increased recurrence and death from gastric cancer[J]. Ann Surg Oncol, 2012, 19(7): 2088-2094. DOI:10.1245/s10434-012-2230-9 |

| [15] |

Agudo A, Sala N, Pera G, et al. Polymorphisms in metabolic genes related to tobacco smoke and the risk of gastric cancer in the European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition[J]. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 2006, 15(12): 2427-2434. DOI:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0072 |

| [16] |

Lee K, Cáceres D, Varela N, et al. Variantes alélicas de CYP1A1 y GSTM1 como biomarcadores de susceptibilidad a cáncer gástrico: influencia de los hábitos tabáquico y alcohólico[J]. Rev Med Chil, 2006, 134(9): 1107-1115. DOI:10.4067/s0034-98872006000900004 |

| [17] |

Boccia S, Sayed-Tabatabaei FA, Persiani R, et al. Polymorphisms in metabolic genes, their combination and interaction with tobacco smoke and alcohol consumption and risk of gastric cancer: a case-control study in an Italian population[J]. BMC Cancer, 2007, 7: 206. DOI:10.1186/1471-2407-7-206 |

| [18] |

Poplawski T, Tomaszewska K, Galicki M, et al. Promoter methylation of cancer-related genes in gastric carcinoma[J]. Exp Oncol, 2008, 30(2): 112-116. |

| [19] |

Rota M, Pelucchi C, Bertuccio P, et al. Alcohol consumption and gastric cancer risk—A pooled analysis within the StoP project consortium[J]. Int J Cancer, 2017, 141(10): 1950-1962. DOI:10.1002/ijc.30891 |

| [20] |

Wang PL, Xiao FT, Gong BC, et al. Alcohol drinking and gastric cancer risk: a meta-analysis of observational studies[J]. Oncotarget, 2017, 8(58): 99013-99023. DOI:10.18632/oncotarget.20918 |

| [21] |

Ren JS, Kamangar F, Forman D, et al. Pickled food and risk of gastric cancer—a systematic review and meta-analysis of English and Chinese literature[J]. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 2012, 21(6): 905-915. DOI:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0202 |

| [22] |

李健, 马林科, 闫晨薇, 等. 宁夏海原县胃癌癌前病变危险因素分析[J]. 现代肿瘤医学, 2021, 29(14): 2530-2535. Li J, Ma LK, Yan CW, et al. Risk factors for precancerous lesions of gastric cancer in Haiyuan county, Ningxia[J]. Mod Oncol, 2021, 29(14): 2530-2535. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1672-4992.2021.14.029 |

| [23] |

Persson C, Sasazuki S, Inoue M, et al. Plasma levels of carotenoids, retinol and tocopherol and the risk of gastric cancer in Japan: a nested case-control study[J]. Carcinogenesis, 2008, 29(5): 1042-1048. DOI:10.1093/carcin/bgn072 |

| [24] |

Shimazu T, Wakai K, Tamakoshi A, et al. Association of vegetable and fruit intake with gastric cancer risk among Japanese: a pooled analysis of four cohort studies[J]. Ann Oncol, 2014, 25(6): 1228-1233. DOI:10.1093/annonc/mdu115 |

| [25] |

Fang XX, Wei JY, He XY, et al. Landscape of dietary factors associated with risk of gastric cancer: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies[J]. Eur J Cancer, 2015, 51(18): 2820-2832. DOI:10.1016/j.ejca.2015.09.010 |

| [26] |

Rugge M. Gastric cancer risk: between genetics and lifestyle[J]. Lancet Oncol, 2020, 21(10): 1258-1260. DOI:10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30432-0 |

| [27] |

Lin YL, Wu CC, Yan W, et al. Sociodemographic and lifestyle factors in relation to gastric cancer in a high-risk region of china: a matched case-control study[J]. Nutr Cancer, 2020, 72(3): 421-430. DOI:10.1080/01635581.2019.1638425 |

| [28] |

Park B, Shin A, Park SK, et al. Ecological study for refrigerator use, salt, vegetable, and fruit intakes, and gastric cancer[J]. Cancer Causes Control, 2011, 22(11): 1497-1502. DOI:10.1007/s10552-011-9823-7 |

| [29] |

Yan SJ, Gan Y, Song XY, et al. Association between refrigerator use and the risk of gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies[J]. PLoS One, 2018, 13(8): e0203120. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0203120 |

| [30] |

Hoang BV, Lee J, Choi IJ, et al. Effect of dietary vitamin C on gastric cancer risk in the Korean population[J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2016, 22(27): 6257-6267. DOI:10.3748/wjg.v22.i27.6257 |

| [31] |

Krejs GJ. Gastric cancer: epidemiology and risk factors[J]. Digest Dis, 2010, 28(4/5): 600-603. DOI:10.1159/000320277 |

| [32] |

Tsugane S. Salt, salted food intake, and risk of gastric cancer: epidemiologic evidence[J]. Cancer Sci, 2005, 96(1): 1-6. DOI:10.1111/j.1349-7006.2005.00006.x |

2022, Vol. 43

2022, Vol. 43