文章信息

- 朱标, 丁昌棉, 蒋清青, 翟萌曦, 田家玮, 俞斌, 燕虹.

- Zhu Biao, Ding Changmian, Jiang Qingqing, Zhai Mengxi, Tian Jiawei, Yu Bin, Yan Hong

- 女同性恋者童年期不良经历与成年期物质使用行为的相关性分析

- Associations between adverse childhood experiences and adulthood substance use among lesbians

- 中华流行病学杂志, 2022, 43(2): 248-253

- Chinese Journal of Epidemiology, 2022, 43(2): 248-253

- http://dx.doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn112338-20210812-00636

-

文章历史

收稿日期: 2021-08-12

2. 德宏傣族景颇族自治州人民医院病案管理科, 芒市 678400

2. Department of Medical Record, The People's Hospital of Dehong Dai and Jingpo Autonomous Prefecture, Mangshi 678400, China

在全球范围内,吸烟、饮酒以及物质使用是影响人群健康的重大公共卫生问题,是导致死亡、疾病和残疾的主要可预防原因[1-5]。物质使用行为还会增加社会经济负担,美国2017年因吸毒增加的医疗和犯罪成本、生产力损失和过早死亡等,造成的经济损失多达1 930亿美元[6]。一些研究发现,女同性恋者通常比异性恋者具有更高的物质使用行为[7-11]。美国芝加哥的一项研究表明,女同性恋者的吸烟率是普通女性吸烟率的1.87倍[7]。Aromin[8]在其研究中表示性少数人群作为一个在自我认同发展方面经历了独特挑战的群体,通常面临更大的物质滥用风险。英国的一项横断面调查显示,女同性恋者和双性恋者的危险饮酒率(19.0%和24.4%)高于异性恋者(8.3%)[9]。童年期不良经历(adverse childhood experiences,ACE)指成年人在18岁之前经历的负性生活事件,主要包括虐待、忽视或家庭功能障碍[12-13],在普通人群中开展的多项研究发现,ACE与成年期吸烟、饮酒、吸毒等物质使用行为[6, 14-15]、危险性行为[16]等密切相关,可作为预测成年期健康危害行为的重要因素[6, 14-16]。而女同性恋者通常比普通人群具有更高的ACE发生率[17]。本研究分析女同性恋者ACE与成年期物质使用行为的状况,探究两者间的关系,为识别物质使用行为的高风险人群、采取针对性的干预措施提供依据。

对象与方法1. 研究对象:女同性恋者,纳入标准:①年龄≥16岁女性;②自我报告性取向为同性恋、双性恋;③知情同意。本研究通过武汉大学健康学院医学伦理学委员会审批(批准文号:2018YF0100)。

2. 研究内容和方法:2018年7-12月,在北京市女同性恋社会组织LesPark的协助下,采用方便抽样的方式从参加例行的艾滋病自愿咨询检测服务、外展活动以及同伴推荐的女同性恋者中招募研究对象。通过文献研究及专家咨询,并结合相关国际通用量表,设计调查问卷,由经过统一培训的调查员采用问卷星(www.wjx.cn)进行线上调查,调查内容包括研究对象的一般人口学特征、ACE、物质使用行为状况等。

(1)ACE:量表由Kaiser-CDC实验室开发,通过3个维度的10个条目调查研究对象在18岁以前所经历的多种负性事件,包括虐待(情感虐待、身体虐待和性虐待)、忽视(情感忽视、家庭忽视)和家庭功能障碍(目睹母亲被虐待、家人物质滥用、家人有精神问题、父母分居或离异、家庭成员服刑)。该量表在中国人群中应用有较好的效度和信度[18],本研究中其Cronbach's α系数为0.67。

(2)物质使用行为:吸烟行为通过询问最近30 d的烟草使用状况测量[19],回答“是”即表示当前有吸烟行为。饮酒和物质使用行为采用WHO制定的酒精、烟草和精神活性物质使用相关问题筛查量表(The Alcohol,Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test,ASSIST)测量[20]。汪文文等[21]在中国人群中开展的研究发现,该量表具有较好的效度和信度。本研究共包含Assist量表7个条目,用于测量过去3个月酒精、大麻、可卡因、苯丙胺类兴奋剂以及致幻剂、吸入剂、镇静剂、阿片类等物质使用情况。每个条目对应5个频率,包括“从来没有用过” “1或2次” “每月1次” “每周1次”和“几乎每天1次”。酒精使用如果回答“每周1次”“几乎每天1次”,则认为有饮酒行为[22-23];对于大麻、可卡因等物质,回答过去3个月有过任何一种服用经历,即认为有物质使用行为[22-23];本研究该量表Cronbach's α为0.71。

3. 统计学分析:使用SPSS 22.0软件进行统计学分析。利用x±s、频数与构成比描述定量和定性资料;χ2检验、两独立样本t检验用于单因素分析;多因素logistic回归模型用于分析女同性恋者物质使用行为与ACE的关系。双侧检验,检验水准α=0.05。

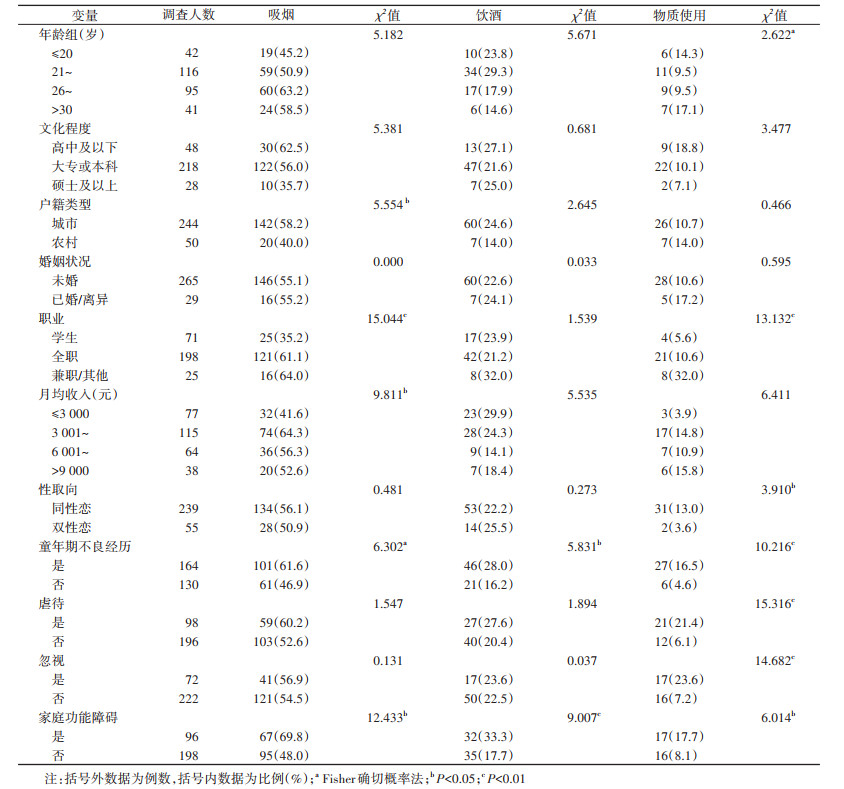

结果1. 一般情况:共发放问卷335份,回收307份,问卷回收率为91.6%,剔除13份关键变量缺失问卷,剩余有效问卷294份,有效问卷回收率为87.8%。294名调查对象中,≤20、21~、26~和 > 30岁者分别占14.3%(42/294)、39.5%(116/294)、32.3%(95/294)和13.9%(41/294)。大专或本科文化程度者占74.2%(218/294),硕士及以上文化程度者占9.5%(28/294)。来自城市者占83.0%(244/294),未婚者占90.1%(265/294)。全职、学生、兼职/其他职业者分别占67.4%(198/294)、24.1%(71/294)、8.5%(25/294)。月均收入3 001~6 000元者占39.1%(115/294)。自我报告性取向为同性恋和双性恋的分别占81.3%(239/294)和18.7%(55/294)。自我报告曾有过ACE、虐待经历、忽视经历和家庭功能障碍经历的分别占55.8%(164/294)、33.3%(98/294)、24.5%(72/294)、和32.7%(96/294)。见表 1。

2. 物质使用行为状况:294名调查对象中,55.1%(162/294)报告过去30 d有吸烟行为,22.8%(67/294)报告最近3个月内至少每周都饮酒,11.2%(33/294)报告过去3个月内曾有过物质使用行为。来自城市的女同性恋者吸烟率(58.2%)高于来自农村者(40.0%);相对于其他职业女同性恋,学生的吸烟率(35.2%)较低;月均收入≤3 000元者的吸烟率(41.6%)低于月均收入 > 3 000元者。相对于学生(5.6%)和有全职工作(10.6%)的女同性恋者,兼职/其他工作者(32.0%)物质使用率更高;同性恋者(13.0%)物质使用率高于双性恋者(3.6%)。见表 1。

3. 女同性恋者物质使用行为与ACE关系:

(1)不同ACE女同性恋者物质使用行为状况:报告有ACE的女同性恋者吸烟、饮酒和物质使用率均高于无ACE者(P < 0.05)。进一步分析发现,女同性恋者的家庭功能障碍经历与其吸烟、饮酒和物质使用行为均有关,而忽视和虐待经历只与其物质使用行为相关。见表 1。

(2)女同性恋者物质使用行为与ACE关系的logistic回归分析:分别以吸烟、饮酒以及物质使用行为作为因变量,将单因素分析中有意义的人口学特征、ACE以及既往研究有重要意义的社会人口学特征变量纳入多因素logistic回归模型分析,各变量依次纳入模型1(社会人口学特征+ACE);模型2(社会人口学特征+ACE类型)。在控制了社会人口学特征后,有ACE者吸烟的可能性是无ACE的1.87倍(95%CI:1.13~3.08)、饮酒为2.13倍(95%CI:1.18~3.84)、物质使用为3.33倍(95%CI:1.29~8.61);从ACE类型看,有家庭功能障碍经历的女同性恋者相比于无此经历者,吸烟(OR=2.60,95%CI:1.46~4.62)和饮酒(OR=2.65,95%CI:1.44~4.87)的可能性较高;有虐待经历者的物质使用的可能性是无此经历者的3.17倍(95%CI:1.26~7.96)。相对于职业为兼职或其他的女同性恋者,学生物质使用行为的风险较低。见表 2。

研究发现,我国女同性恋者过去30 d吸烟率为55.1%、过去3个月内至少每周饮酒率为22.8%,过去3个月物质使用率为11.2%,远高于我国普通女性人群的2.3%[24]、2.1%[25]和1.1%[26]。同既往的研究结果一致[7, 9, 27]。2011-2012年,在美国芝加哥地区进行的一项纵向研究显示[7],女性少数群体的吸烟率为29.6%,明显高于普通女性人群(14.8%)。Shahab等[9]在英国开展一项研究也发现,与性取向为异性恋者(15.5%)相比,女同性恋者(24.9%)和双性恋者(32.4%)烟草使用行为的比例较高。同时,2004年美国开展一项调查人群物质使用行为的发现[27],与性取向为异性恋者相比,女同性恋和双性恋者的饮酒(20.1%和25.0%比8.4%)和物质使用行为(12.6%和14.1%比3.1%)均处于较高水平。女同性恋者物质使用行为较普遍,该人群作为性少数群体,常面临较高的压力和负性经历,如社会歧视[28-29]和ACE[30-31]等有关。既往在其他人群开展的研究已发现,人们在面对压力时通常采取吸烟和饮酒等方式缓解或应对[32-33]。

多项在普通人群开展的研究发现,ACE是影响人群物质使用行为的重要因素[6, 14-15]。本研究发现,研究对象曾有过ACE者占55.8%,明显高于我国普通人群报告的ACE比例(36.15%)[34]。另外,研究对象自我报告有过虐待经历、家庭功能障碍经历的分别占33.3%和32.7%,均高于我国普通成年女性(27.48%和27.39%)[35]。多因素logistic回归分析结果显示,ACE与女同性恋者的吸烟、饮酒和物质使用行为均有关,童年期家庭功能障碍经历主要与吸烟和饮酒行为相关,虐待经历仅与物质使用行为相关,忽视经历与以上这些行为均未有明显的相关性,这与Westermair等[36]研究发现的童年期家庭功能障碍与不良的健康行为(吸烟、酒精依赖)和较差的社会成就(文化程度、收入)相关的结果一致,而童年期虐待和忽视没有此类效应。Amemiya等[37]针对日本和芬兰人群研究发现,经历过童年期父母离异等家庭功能障碍的个体可能与其当前吸烟行为有关。而Thornberry等[38]发现有童年期虐待等不良经历的人群通常在其成年早期的物质使用和滥用行为的风险较高。

本研究还发现,相比于从事兼职/其他工作的女同性恋者,学生物质使用的风险较低。既往研究也有类似发现,Valois等[39]认为,相比于无兼职工作的学生,从事兼职工作通常物质使用的风险较高。可能原因:一是相比于学生,从事兼职/其他工作的文化程度相对较低,对非法物质使用的认识不够深入,相对于较为封闭的学校环境,社会上较容易接触到非法物质;二是从事兼职/其他工作的个体时间较充裕,生活较闲散,常出现在酒吧、KTV等娱乐场所,这些场所往往是发生物质使用行为的危险场所。

综上所述,女同性恋者具有较普遍的吸烟、饮酒行为以及成年期物质使用行为,并与其ACE具有相关性。应关注该人群生活早期的不良经历,针对有不良经历者采取有效的干预措施如心理疏导等,减少其物质使用行为,降低物质使用行为导致的疾病、死亡等不良健康结局风险。

利益冲突 所有作者声明无利益冲突

作者贡献声明 朱标:数据整理、数据分析、论文撰写、论文修改;丁昌棉:现场调查实施、数据整理;蒋清青、翟萌曦、田家玮、俞斌:研究指导;燕虹:研究设计、论文修改、经费支持

志谢 感谢北京市女同性恋社会组织LesPark工作人员、所有研究对象对本研究的支持和帮助

| [1] |

Ezzati M, Lopez AD. Estimates of global mortality attributable to smoking in 2000[J]. Lancet, 2003, 362(9387): 847-852. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14338-3 |

| [2] |

Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M, et al. Global and regional burden of disease and risk factors, 2001:systematic analysis of population health data[J]. Lancet, 2006, 367(9524): 1747-1757. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68770-9 |

| [3] |

Rehm J, Shield KD. Alcohol and Mortality. Global alcohol-attributable deaths from cancer, liver cirrhosis, and injury in 2010[J]. Alcohol Res, 2013, 35(2): 174-183. |

| [4] |

Anderson P. The monitoring of the State of the World's drinking: What WHO has accomplished and what further needs to be done[J]. Addiction, 2005, 100(12): 1751-1754. DOI:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01241.x |

| [5] |

Fridell M, Hesse M. Psychiatric severity and mortality in substance abusers: A 15-year follow-up of drug users[J]. Addict Behav, 2006, 31(4): 559-565. DOI:10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.05.036 |

| [6] |

LeTendre ML, Reed MB. The effect of adverse childhood experience on clinical diagnosis of a substance use disorder: results of a nationally representative study[J]. Subst Use Misuse, 2017, 52(6): 689-697. DOI:10.1080/10826084.2016.1253746 |

| [7] |

Matthews AK, Steffen A, Hughes T, et al. Demographic, healthcare, and contextual factors associated with smoking status among sexual minority women[J]. LGBT Health, 2017, 4(1): 17-23. DOI:10.1089/lgbt.2016.0039 |

| [8] |

Aromin RA. Substance abuse prevention, assessment, and treatment for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth[J]. Pediatr Clin North Am, 2016, 63(6): 1057-1077. DOI:10.1016/j.pcl.2016.07.007 |

| [9] |

Shahab L, Brown J, Hagger-Johnson G, et al. Sexual orientation identity and tobacco and hazardous alcohol use: findings from a cross-sectional English population survey[J]. BMJ Open, 2017, 7(10): e015058. DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015058 |

| [10] |

Emslie C, Lennox J, Ireland L. The role of alcohol in identity construction among LGBT people: a qualitative study[J]. Sociol Health Illn, 2017, 39(8): 1465-1479. DOI:10.1111/1467-9566.12605 |

| [11] |

Newcomb ME, Heinz AJ, Mustanski B. Examining risk and protective factors for alcohol use in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth: a longitudinal multilevel analysis[J]. J Stud Alcohol Drugs, 2012, 73(5): 783-793. DOI:10.15288/jsad.2012.73.783 |

| [12] |

Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study[J]. Am J Prev Med, 1998, 14(4): 245-258. DOI:10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8 |

| [13] |

Bellis MA, Hughes K, Leckenby N, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and associations with health-harming behaviours in young adults: surveys in eight eastern European countries[J]. Bull World Health Organ, 2014, 92(9): 641-655. DOI:10.2471/Blt.13.129247 |

| [14] |

Naal H, El Jalkh T, Haddad R. Adverse childhood experiences in substance use disorder outpatients of a Lebanese addiction center[J]. Psychol Health Med, 2018, 23(9): 1137-1144. DOI:10.1080/13548506.2018.1469781 |

| [15] |

Allem JP, Soto DW, Baezconde-Garbanati L, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and substance use among Hispanic emerging adults in Southern California[J]. Addict Behav, 2015, 50: 199-204. DOI:10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.06.038 |

| [16] |

Hillis SD, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and sexual risk behaviors in women: a retrospective cohort study[J]. Family Plann Perspect, 2001, 33(5): 206-211. DOI:10.2307/2673783 |

| [17] |

Andersen JP, Blosnich J. Disparities in adverse childhood experiences among sexual minority and heterosexual adults: results from a multi-state probability-based sample[J]. PLoS One, 2013, 8(1): e54691. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0054691 |

| [18] |

Ding YY, Lin HJ, Zhou L, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and interaction with methamphetamine use frequency in the risk of methamphetamine-associated psychosis[J]. Drug Alcohol Depen, 2014, 142: 295-300. DOI:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.06.042 |

| [19] |

Windle M, Haardörfer R, Getachew B, et al. A multivariate analysis of adverse childhood experiences and health behaviors and outcomes among college students[J]. J Am College Health, 2018, 66(4): 246-251. DOI:10.1080/07448481.2018.1431892 |

| [20] |

WHO ASSIST Working Group. The alcohol, smoking and substance involvement screening test (ASSIST): development, reliability and feasibility[J]. Addiction, 2002, 97(9): 1183-1194. DOI:10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00185.x |

| [21] |

汪文文, 李煦, 杜江, 等. 四川省某地区物质使用情况调查: 酒精、烟草和精神活性物质使用相关问题筛查测试(ASSIST)[J]. 中国药物依赖性杂志, 2015, 24(5): 367-371. W W, Li X, Du J, et al. Investigating the substance use problem in the community of Sichuan province with ASSIST[J]. Chin J Drug Depend, 2015, 24(5): 367-371. DOI:10.13936/j.cnki.cjdd1992.2015.010 |

| [22] |

Gamarel KE, Brown L, Kahler CW, et al. Prevalence and correlates of substance use among youth living with HIV in clinical settings[J]. Drug Alcohol Depen, 2016, 169: 11-18. DOI:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.10.002 |

| [23] |

Gamarel KE, Nichols S, Kahler CW, et al. A cross-sectional study examining associations between substance use frequency, problematic use and STIs among youth living with HIV[J]. Sex Transm Infect, 2018, 94(4): 303-307. DOI:10.1136/sextrans-2017-053334 |

| [24] |

Zhang M, Liu SW, Yang L, et al. Prevalence of smoking and knowledge about the hazards of smoking among 170000 Chinese adults, 2013-2014[J]. Nicotine Tob Res, 2019, 21(12): 1644-1651. DOI:10.1093/ntr/ntz020 |

| [25] |

Im PK, Millwood IY, Guo Y, et al. Patterns and trends of alcohol consumption in rural and urban areas of China: findings from the China Kadoorie Biobank[J]. BMC Public Health, 2019, 19: 217. DOI:10.1186/s12889-019-6502-1 |

| [26] |

Jia ZW, Jin YY, Zhang LL, et al. Prevalence of drug use among students in mainland China: A systematic review and meta-analysis for 2003-2013[J]. Drug Alcohol Depen, 2018, 186: 201-206. DOI:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.12.047 |

| [27] |

Mccabe SE, Hughes TL, Bostwick WB, et al. Sexual orientation, substance use behaviors and substance dependence in the United States[J]. Addiction, 2009, 104(8): 1333-1345. DOI:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02596.x |

| [28] |

Hughes TL, Johnson TP, Steffen AD, et al. Lifetime victimization, hazardous drinking, and depression among heterosexual and sexual minority women[J]. LGBT Health, 2014, 1(3): 192-148. DOI:10.1089/lgbt.2014.0014 |

| [29] |

Austin A, Herrick H, Proescholdbell S. Adverse childhood experiences related to poor adult health among lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals[J]. Am J Public Health, 2016, 106(2): 314-320. DOI:10.2105/Ajph.2015.302904 |

| [30] |

Logie CH, Lacombe-Duncan A, Poteat T, et al. Syndemic factors mediate the relationship between sexual stigma and depression among sexual minority women and gender minorities[J]. Womens Health Issues, 2017, 27(5): 592-599. DOI:10.1016/j.whi.2017.05.003 |

| [31] |

Hua BY, Yang VF, Goldsen KF. LGBT older adults at a crossroads in Mainland China: the intersections of stigma, cultural values, and structural changes within a shifting context[J]. Int J Aging Hum Dev, 2019, 88(4): 440-456. DOI:10.1177/0091415019837614 |

| [32] |

González AM, Cruz SY, Ríos JL, et al. Alcohol consumption and smoking and their associations with socio-demographic characteristics, dietary patterns, and perceived academic stress in Puerto Rican college students[J]. P R Health Sci J, 2013, 32(2): 82-88. |

| [33] |

Happell B, Reid-Searl K, Dwyer T, et al. How nurses cope with occupational stress outside their workplaces[J]. Collegian, 2013, 20(3): 195-199. DOI:10.1016/j.colegn.2012.08.003 |

| [34] |

Cheung S, Huang CC, Zhang CC. Passion and persistence: investigating the relationship between adverse childhood experiences and grit in college Students in China[J]. Front Psychol, 2021, 12: 642956. DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.642956 |

| [35] |

Chang XN, Jiang XY, Mkandarwire T, et al. Associations between adverse childhood experiences and health outcomes in adults aged 18-59 years[J]. PLoS One, 2019, 14(2): e0211850. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0211850 |

| [36] |

Westermair AL, Stoll AM, Greggersen W, et al. All unhappy childhoods are unhappy in their own way -differential impact of dimensions of adverse childhood experiences on adult mental health and health behavior[J]. Front Psychiatry, 2018, 9: 198. DOI:10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00198 |

| [37] |

Amemiya A, Fujiwara T, Shirai K, et al. Association between adverse childhood experiences and adult diseases in older adults: a comparative cross-sectional study in Japan and Finland[J]. BMJ Open, 2019, 9(8): e024609. DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024609 |

| [38] |

Thornberry TP, Henry KL, Ireland TO, et al. The causal impact of childhood-limited maltreatment and adolescent maltreatment on early adult adjustment[J]. J Adolescent Health, 2010, 46(4): 359-365. DOI:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.09.011 |

| [39] |

Valois RF, Dunham ACA, Jackson KL, et al. Association between employment and substance abuse behaviors among public high school adolescents[J]. J Adolescent Health, 1999, 25(4): 256-263. DOI:10.1016/s1054-139x(99)00039-7 |

2022, Vol. 43

2022, Vol. 43