文章信息

- 唐上晴, 陈雯, 赵培祯, 郑和平, 杨斌, 史李铄, 凌莉, 王成.

- Tang Shangqing, Chen Wen, Zhao Peizhen, Zheng Heping, Yang Bin, Shi Lishuo, Ling Li, Wang Cheng

- 广东省2005-2017年胎传梅毒时空分布特征及相关因素空间面板数据分析

- Spatiotemporal distribution and related factors of congenital syphilis in Guangdong province from 2005 to 2017: a spatial panel data analysis

- 中华流行病学杂志, 2021, 42(4): 620-625

- Chinese Journal of Epidemiology, 2021, 42(4): 620-625

- http://dx.doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn112338-20200807-01043

-

文章历史

收稿日期: 2020-08-07

2. 南方医科大学皮肤病医院, 广州 510091;

3. 中山大学附属第六医院, 广州 510655

2. Dermatology Hospital, Southern Medical University, Guangzhou 510091, China;

3. The Sixth Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou 510655, China

胎传梅毒是由苍白密螺旋体苍白亚种经母体胎盘进入胎儿血液循环所引起的多系统性疾病。孕产妇感染梅毒后若未得到及时的治疗,便会感染胎儿引起胎传梅毒,导致早产、死产、低出生体重以及新生儿死亡等不良妊娠结局[1]。在所有梅毒分类中,胎传梅毒的疾病负担远高于其他分期梅毒[2],每年可造成超过120万的新发病例[3]及30万新生儿的死亡[4],是一个严重的全球公共卫生问题。我国于2010年提出10年内基本消灭胎传梅毒的防治目标。以往对于胎传梅毒的相关因素研究多为临床诊断治疗层面及描述性流行病学研究,较少针对其发病的宏观相关因素进行全面的分析,而且胎传梅毒发病具有空间聚集性[5],忽略相邻地区间发病的空间相关性会对相关因素的分析结果造成偏倚[6]。本研究利用现有监测数据的时空信息,通过空间面板数据模型对胎传梅毒发病的空间相关性分析,进行胎传梅毒的时空分布及宏观相关因素的探索,为卫生部门制定胎传梅毒防控策略提供参考依据。

资料与方法1. 资料来源:2005-2017年广东省21个地级市的梅毒病例报告数据来源于广东省皮肤性病防治中心,诊断和上报参照《梅毒诊断标准(WS 273-2007)》[7]。相关因素中宏观经济(人均地区生产总值、各产业生产总值占比)[6, 8-10]、人口学特征(户籍人口密度、净迁移率)以及孕产妇保健(产前检查率、产妇系统管理率、住院分娩率)等资料均来源于文献[11-12]。广东省地图来源于广东省自然资源厅地理信息公共服务平台。

2. 统计学分析:

(1)胎传梅毒时空分布描述:利用Excel 2010软件描绘胎传梅毒的发病率曲线,使用ArcGIS 10.2软件描绘胎传梅毒的发病地图,描述胎传梅毒发病随时间及空间变化情况。

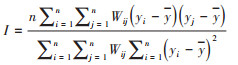

(2)胎传梅毒空间相关性分析:对胎传梅毒发病进行全域空间自相关分析,计算Moran’s I值并对其进行检验。检验水准α=0.05。Moran’s I值公式[13]:

其中,n表示空间单位的个数,Wij为空间权重矩阵,y表示不同空间单位的胎传梅毒发病率。对Moran’s I值进行假设检验,若检验有统计学意义,则提示广东省胎传梅毒发病情况具有空间相关性。

(3)胎传梅毒相关因素分析:2005-2017年广东省21个地级市的发病率及相关因素数据具有面板数据的特点,因此采用面板数据模型进行分析。以胎传梅毒发病率为因变量,女性一期、二期梅毒的发病率、社会经济和社会人口学因素指标为自变量进行模型构建。

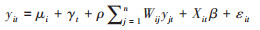

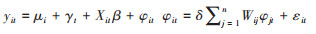

空间面板数据模型在普通面板数据模型的基础上,引入空间权重矩阵Wij将不同空间单元间的地理信息纳入模型[14],对空间相关性进行量化[15]。根据空间相关性来源的不同,空间面板数据模型可分为空间滞后模型(spatial lag model,SLM)以及空间误差模型(spatial error model,SEM)。两个模型的主要区别在于空间滞后模型假定空间相关性的存在是由于相邻地区间因变量的相互影响,而空间误差模型的空间相关性是相邻地区不被观测到的变量所致。模型基本形式为[16]:

空间滞后模型:

空间误差模型:

其中,yit表示i地区t时刻上的胎传梅毒发病率。μi和γt为不同空间单元及不同时点的截距项。ρ和δ分别为空间滞后系数及空间误差系数,反映了空间相关性。Xit表示自变量的观测值,β表示对应自变量的系数。εit为随机误差项,φit表示i地区t时刻的空间误差项,φjt表示j地区t时刻的空间误差项。

数据是否适用于空间面板数据模型以及模型形式的选择可通过拉格朗日乘数(lagrange multiplier test,LM)检验和稳健LM检验来确定[15, 17]。先对数据进行普通回归分析,进行LM检验。如果LM检验中滞后检验统计量(LM-Lag)和误差检验统计量(LM-Error)均不显著,说明数据不适用于空间面板数据模型。如果LM-Lag和LM-Error统计量中有一个显著,则选择统计量显著的空间面板数据模型形式。两者均显著则进一步采用稳健LM检验。稳健LM检验可修正LM检验统计量中空间滞后效应与空间误差效应互相干扰的情况。若稳健LM-Error更显著,则采用空间误差模型;若稳健LM-Lag更显著,则采用空间滞后模型[18]。在将发病率、人口密度及人均生产总值等非正态数据纳入模型之前,对其进行对数转化来减少原始数据的过度离散。最后将采用R2和似然比指标来评价模型的拟合优度[19-20]。模型的选择与构建由Matlab R 2019a软件完成[17]。

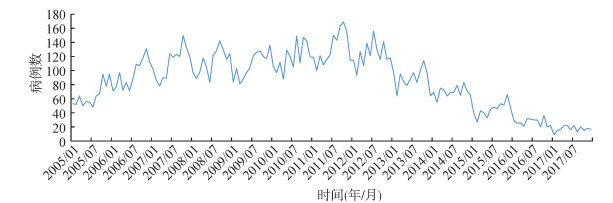

结果1. 时间分布特点:2005-2017年,广东省上报胎传梅毒病例13 361例。月发病9~169例。时间分布上,胎传梅毒发病人数从2005年开始逐年上升,至2011年到达最高峰后,呈现下降趋势。胎传梅毒发病呈现一定的季节周期性,每年的发病高峰大多集中于8-12月。

2. 空间分布特点:2005-2017年广东省胎传梅毒Moran’s I=0.270,Z=2.404,P=0.016,表明发病呈正向空间相关性,说明胎传梅毒病例存在一定程度的聚集状态。2005-2011年,胎传梅毒高发城市集中在珠三角地区,尤其是广州、东莞、中山、珠海及佛山5个城市,年发病率大多超过150.00/10万活产儿(图 2)。2011年以后,珠三角地区发病率逐渐下降,粤东、粤西及粤北地区的发病率逐渐升高,与珠三角地区的发病率差异逐渐缩小。直至2017年,广东省胎传梅毒发病率得到控制,大部分地级市年发病率逐渐下降至40.00/10万活产儿以内。

|

| 图 1 2005-2017年广东省胎传梅毒月发病例数曲线 |

|

| 注:2006、2008、2010、2012、2014年未列出 图 2 2005-2017年广东省胎传梅毒发病率空间分布示意图 |

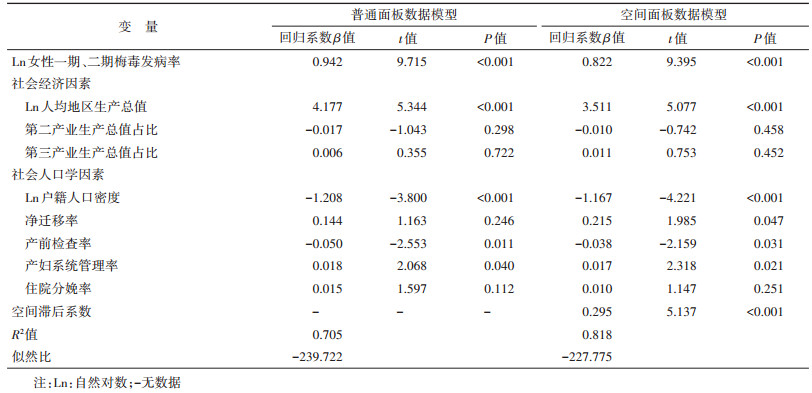

3. 相关因素分析:空间面板数据模型LM检验结果显示,稳健LM-Lag统计量比稳健LM-Error统计量更显著,这表明本数据更适合于空间滞后面板数据模型(表 1)。比较胎传梅毒与相关因素的普通面板数据模型与空间滞后面板数据模型,空间滞后面板数据模型R2=81.8%,似然比值为-227.775,拟合程度优于普通面板模型(表 2)。在空间滞后面板数据模型中,空间滞后系数为0.295(P < 0.001),说明胎传梅毒发病率与相邻地区的胎传梅毒发病率呈正相关。在控制了地区之间的相互影响后,女性一期、二期梅毒发病率与胎传梅毒发病率呈正相关(β=0.822,P < 0.001)。在社会因素中,人均地区生产总值(β=3.511,P < 0.001)、净迁移率(β=0.215,P=0.047)与产妇系统管理率(β=0.017,P=0.021)与胎传梅毒发病率呈正相关。户籍人口密度(β=-1.167,P < 0.001)、产前检查率(β=-0.038,P=0.031)与胎传梅毒发病率呈负相关。其余因素对胎传梅毒发病的影响无统计学意义。

我国自2004年建成覆盖全国的法定传染病网络实时直报信息平台,其监测数据在一定程度上可反映疾病的发病规律,在传染病的预防方面起到了不可或缺的作用。如何实现监测数据价值的最大化是公共卫生领域的重要研究方向。本研究发现,2005-2017年广东省胎传梅毒呈现一定程度的季节性变化及空间聚集性,整体为先上升后下降的发病趋势。校正空间聚集性的影响后,胎传梅毒发病率相关因素包括女性一期、二期梅毒发病率、人均地区生产总值、户籍人口密度、净迁移率、产妇系统管理率以及产前检查率。

广东省胎传梅毒的时空分布从时间维度来看,主要集中在夏秋季,这与其他国家的研究结果一致[21]。从空间维度来看,该病先从珠三角地区高发,随后蔓延至偏内陆地区,这与我国梅毒的疾病负担由沿海转移至内陆省份的趋势相符[22]。同时,从发病率地图可以发现,广东省胎传梅毒的发病率存在一定程度的正向空间聚集趋势,空间面板数据模型的结果也印证了这个观点,胎传梅毒发病率不仅与该城市的某些属性变量有关,还与邻近城市的发病率有关。若邻近城市胎传梅毒发病率较高,那该城市往往也处于胎传梅毒高发病风险之中。

空间面板数据研究结果表明,女性一期、二期梅毒发病率与胎传梅毒呈正相关,与之前的研究结果一致[23]。一期、二期梅毒作为梅毒发病的早期阶段,是整个患病阶段感染性及传播能力最强的时期,且一期、二期梅毒女性高发年龄段处于育龄期[24],倘若得不到及时的治疗,便可作为传染源,增加围产期梅毒垂直传播的风险。因此,对于一期、二期梅毒及胎传梅毒,需要做到同时预防与控制,加强两者防治的有效结合,才能从源头上阻断胎传梅毒的发病。

本研究从社会经济、人口学以及孕产妇产前保健3个方面进行相关因素分析。首先在经济方面,15世纪末的欧洲地区,梅毒通常被称为“上流社会的勋章”,这反映了梅毒与经济自古以来的密切关系。本研究模型结果发现胎传梅毒发病与经济水平呈正相关,但与产业占比关系不大。这可能是因为在发达地区性行业的快速发展[25]与人们薄弱的健康防护意识的相互作用下,不安全性行为增加,孕产妇健康保障未得到足够重视,进而增加了STD垂直传播的风险。另一方面,经济落后地区病例上报制度仍未完善,报告覆盖率较低,漏报率较高,也可能是造成该结果的原因之一[26]。因此,对于经济发达地区应采取更严格的传染病预防措施,加强经济发达地区的健康教育,倡导安全性行为,提高健康保健意识,减少育龄女性梅毒患病率,控制胎传梅毒的传染源。

在人口学方面,本研究发现,人口的动态流动同样可能是导致胎传梅毒高发的原因,这与淋病的研究结果相似[6]。广东省是人口流入大省,流动人口占近30%[27],人口的迁移促进了STD蔓延[28]。流动妇女的文化程度较低、健康意识较弱[29]。同时由于户籍制度的影响,该人群的医保覆盖率低[30],异地医保结算困难,基本公共卫生服务得不到保障[31]。这可能导致了人口迁移率高的地区胎传梅毒发病率较高,需对该地区进行重点防护。此外,产前检查可以明确降低胎传梅毒的发生[22]。2011年以来,我国对母婴传播STD采取了防控措施,加强产前检查。该项措施有利于对孕产妇及婴儿进行早发现早干预,获得良好的治疗效果。而产妇系统管理率与胎传梅毒率呈正相关,产生这个现象的原因可能与我国胎传梅毒的上报流程有关,在孕产妇建档并纳入系统后,才有可能进行胎传梅毒的上报[32]。在这个流程背景下,档案系统的完善便会呈现出与发病率的正相关。

本研究存在不足。首先,梅毒监测数据准确性会受到就诊情况、监测系统能力等因素影响,可能存在偏倚。其次,本研究仅能表示各个因素与胎传梅毒发病率间的相关性而非因果关系,还需今后进一步的深入研究。

综上所述,2005-2017年广东省胎传梅毒发病具有季节性与空间聚集性。相邻省份间的胎传梅毒发病率具有相关性。经济发达、净迁移率较高的地区胎传梅毒发病风险较高,需重点防治。加强对女性一期、二期梅毒的监测,控制发病率,提高孕产妇产前检查率,有利于胎传梅毒的预防。

利益冲突 所有作者均声明不存在利益冲突

| [1] |

Gomez GB, Kamb ML, Newman LM, et al. Untreated maternal syphilis and adverse outcomes of pregnancy: a systematic review and Meta-analysis[J]. Bull World Health Organ, 2013, 91(3): 217-226. DOI:10.2471/BLT.12.107623 |

| [2] |

邹亚明, 刘凤英, 陈磊, 等. 广东省2005-2014年梅毒流行趋势和疾病负担[J]. 中山大学学报: 医学科学版, 2016, 37(1): 142-147. Zou YM, Liu FY, Chen L, et al. Epidemiological trend and disease burden of syphilis in Guangdong province, 2005-2014[J]. J Sun Yat-sen Univ: Med Sci, 2016, 37(1): 142-147. DOI:10.13471/j.cnki.j.sun.yat-sen.univ(med.sci).2016.0025 |

| [3] |

World Health Organization. Advancing MDGs 4, 5 and 6: impact of congenital syphilis elimination: partner brief[R]. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2010.

|

| [4] |

World Health Organization. Global health sector strategy on sexually transmitted infections 2016-2021: toward ending STIs[R]. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2016.

|

| [5] |

王雅洁, 龚向东, 岳晓丽, 等. 中国2010年和2015年胎传梅毒空间分布特征[J]. 中华皮肤科杂志, 2018, 51(5): 337-340. Wang YJ, Gong XD, Yue XL, et al. Spatial distribution characteristics and patterns of congenital syphilis in 2010 and 2015 in China[J]. Chin J Dermatol, 2018, 51(5): 337-340. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0412-4030.2018.05.004 |

| [6] |

Cao WT, Li R, Ying JY, et al. Spatiotemporal distribution and determinants of gonorrhea infections in mainland China: a panel data analysis[J]. Public Health, 2018, 162: 82-90. DOI:10.1016/j.puhe.2018.05.015 |

| [7] |

国家卫生健康委员会. 中华人民共和国卫生行业标准WS 273-2007梅毒诊断标准[EB/OL]. (2007-04-14). http://www.nhc.gov.cn/wjw/s9491/201410/a72a7387653842b09c0c0f10fdfdf9b7.shtml. National Health Commission. Health Industry Standard of the People's Republic of China WS 273-2007 Diagnostic criteria for syphilis[EB/OL]. (2007-04-14). http://www.nhc.gov.cn/wjw/s9491/201410/a72a7387653842b09c0c0f10fdfdf9b7.shtml. |

| [8] |

Krieger N, Waterman PD, Chen JT, et al. Monitoring socioeconomic inequalities in sexually transmitted infections, tuberculosis, and violence: geocoding and choice of area-based socioeconomic measures-the public health disparities geocoding project (US)[J]. Public Health Rep, 2003, 118(3): 240-260. DOI:10.1093/phr/118.3.240 |

| [9] |

Barger AC, Pearson WS, Rodriguez C, et al. Sexually transmitted infections in the Delta Regional Authority: significant disparities in the 252 counties of the eight-state Delta Region Authority[J]. Sex Trans Infect, 2018, 94(8): 611-615. DOI:10.1136/sextrans-2018-053556 |

| [10] |

Ma Y, Zhang T, Liu L, et al. Spatio-Temporal Pattern and Socio-Economic Factors of Bacillary Dysentery at County Level in Sichuan province, China[J]. Sci Rep, 2015, 5: 15264. DOI:10.1038/srep15264 |

| [11] |

广东省统计局, 国家统计局广东调查总队. 广东统计年鉴[M]. 北京: 中国统计出版社, 2014. Guangdong Provincial Bureau of Statistics, Survey Office of the National Bureau of Statistics in Guangdong. Guangdong statistical yearbook[M]. Beijing: China Statistics Press, 2014. |

| [12] |

广东省卫生健康委员会. 广东省卫生健康统计年鉴[EB/OL]. (2018-09-30)[2020-07-01]. http://www.gdhealth.net.cn/html/tongjishuju/tongjiziliao/. Health Commission of Guangdong Province. Guangdong health and family planning statistical yearbook[EB/OL]. (2018-09-30)[2020-07-01]. http://www.gdhealth.net.cn/html/tongjishuju/tongjiziliao/. |

| [13] |

林静静, 张铁威, 李秀央. 疾病时空聚集分析的研究与进展[J]. 中华流行病学杂志, 2020, 41(7): 1165-1170. Lin JJ, Zhang TW, Li XY. Research progress on spatiotemporal clustering of disease[J]. Chin J Epidemiol, 2020, 41(7): 1165-1170. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.cn112338-20190806-00582 |

| [14] |

黄勇, 邓特, 于石成, 等. 空间面板数据模型在传染病监测数据分析中的应用[J]. 中华疾病控制杂志, 2013, 17(4): 277-281. Huang Y, Deng T, Yu SC, et al. Application of Spatial panel data model in data analysis for infectious disease surveillance[J]. Chin J Dis Control Prev, 2013, 17(4): 277-281. |

| [15] |

赵哲, 王海涛, 姜宝法. 监测数据统计分析模型在生态学研究中的应用[J]. 中华流行病学杂志, 2019, 40(8): 1010-1017. Zhao Z, Wang HT, Jiang BF. Applications of statistical models on surveillance data in ecological study[J]. Chin J Epidemiol, 2019, 40(8): 1010-1017. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2019.08.026 |

| [16] |

Elhorst JP. Specification and estimation of spatial panel data models[J]. Int Reg Sci Rev, 2003, 26(3): 244-268. DOI:10.1177/0160017603253791 |

| [17] |

Elhorst JP. Matlab software for spatial panels[J]. Int Reg Sci Rev, 2014, 37(3): 389-405. DOI:10.1177/0160017612452429 |

| [18] |

Anselin L, Bera AK, Florax R, et al. Simple diagnostic tests for spatial dependence[J]. Reg Sci Urban Econ, 1996, 26(1): 77-104. DOI:10.1016/0166-0462(95)02111-6 |

| [19] |

Lee LF, Yu JH. Estimation of spatial autoregressive panel data models with fixed effects[J]. J Econ, 2010, 154(2): 165-185. DOI:10.1016/j.jeconom.2009.08.001 |

| [20] |

Kelejian HH, Prucha IR. Specification and estimation of spatial autoregressive models with autoregressive and heteroskedastic disturbances[J]. J Econ, 2010, 157(1): 53-67. DOI:10.1016/j.jeconom.2009.10.025 |

| [21] |

de Souza JM, Giuffrida R, Ramos APM, et al. Mother-to-child transmission and gestational syphilis: spatial-temporal epidemiology and demographics in a Brazilian region[J]. PLoS Negl Trop Dis, 2019, 13(2): e0007122. DOI:10.1371/journal.pntd.0007122 |

| [22] |

Tao YS, Chen MY, Tucker JD, et al. A nationwide spatiotemporal analysis of syphilis over 21 years and implications for prevention and control in China[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2020, 70(1): 136-139. DOI:10.1093/cid/ciz331 |

| [23] |

Vaules MB, Ramin KD, Ramsey PS. Syphilis in pregnancy: a review[J]. Prim Care Update OB/GYNS, 2000, 7(1): 26-30. DOI:10.1016/S1068-607X(99)00036-0 |

| [24] |

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2018[EB/OL]. (2020-01-01)[2020-07-01]. https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats18/default.htm.

|

| [25] |

Uretsky E. 'Mobile men with money': the socio-cultural and politico-economic context of 'high-risk' behaviour among wealthy businessmen and government officials in urban China[J]. Cult Health Sex, 2008, 10(8): 801-814. DOI:10.1080/13691050802380966 |

| [26] |

岳晓丽, 龚向东, 刘昆仑. 2005年全国淋病与梅毒病例报告覆盖情况分析[J]. 中国艾滋病性病, 2006, 12(6): 538-540. Yue XL, Gong XD, Liu KL. Coverage of gonorrhea and syphilis case reporting in 2005 in China[J]. Chin J AIDS STD, 2006, 12(6): 538-540. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1672-5662.2006.06.020 |

| [27] |

梁宏. 广东省流动人口的特征及其变化[J]. 人口与发展, 2013, 19(4): 46-53, 19. Liang H. Characteristics and changes of floating population in Guangdong Province[J]. Popul Dev, 2013, 19(4): 46-53, 19. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1674-1668.2013.04.006 |

| [28] |

White RG. Commentary: what can we make of an association between human immunodeficiency virus prevalence and population mobility?[J]. Int J Epidemiol, 2003, 32(5): 753-754. DOI:10.1093/ije/dyg265 |

| [29] |

吴霜. 城市低文化流动人口功能性扫盲教育研究——以重庆市渝中区为例[D]. 重庆: 西南大学, 2011. Wu S. The functional literacy study on floating population with less schooling in the city for instance-in Yuzhong district of Chongqing[D]. Chongqing: Southwest University, 2011. |

| [30] |

吴少龙, 凌莉. 流动人口医疗保障的三大问题[J]. 中国卫生政策研究, 2012, 5(6): 30-36. Wu SL, Ling L. Three issues of migrants' health insurance in China[J]. Chin J Health Policy, 2012, 5(6): 30-36. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1674-2982.2012.06.007 |

| [31] |

Zhu LP, Qin M, Du L, et al. Maternal and congenital syphilis in Shanghai, China, 2002 to 2006[J]. Int J Infect Dis, 2010, 14 Suppl 3: e45-48. DOI:10.1016/j.ijid.2009.09.009 |

| [32] |

卫生部办公厅. 关于印发《预防艾滋病、梅毒和乙肝母婴传播工作实施方案》的通知[EB/OL]. (2011-02-28)[2020-07-01]. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/fys/s3581/201102/a0c03b2192a1483384b4f798d9ba603d.shtml. General Office of Ministry of Health. Implementation for preventing vertical transmission of AIDS, syphilis and hepatitis B[EB/OL]. (2011-02-28)[2020-07-01]. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/fys/s3581/201102/a0c03b2192a1483384b4f798d9ba603d.shtml. |

2021, Vol. 42

2021, Vol. 42