文章信息

- 孙殿钦, 曹毛毛, 李贺, 何思怡, 雷林, 彭绩, 李江, 陈万青.

- Sun Dianqin, Cao Maomao, Li He, He Siyi, Lei Lin, Peng Ji, Li Jiang, Chen Wanqing

- 全球前列腺癌筛查指南质量评价

- Quality assessment of global prostate cancer screening guidelines

- 中华流行病学杂志, 2021, 42(2): 227-233

- Chinese Journal of Epidemiology, 2021, 42(2): 227-233

- http://dx.doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn112338-20200806-01033

-

文章历史

收稿日期: 2020-08-06

2. 深圳市慢性病防治中心肿瘤防控科 518020

2. Department of Cancer Prevention and Control, Shenzhen Center for Chronic Disease Control, Shenzhen 518020, China

前列腺癌是全球男性最常见的恶性肿瘤之一。GLOBOCAN数据显示,2018年前列腺癌发病和死亡的世界人口标化率分别为29.3/10万、7.6/10万,分别位列全球男性癌症谱的第2位和第5位[1]。中国前列腺癌的发病率与西方国家相比较低,但近年来呈现了明显的上升趋势[2]。我国最新肿瘤登记年报显示,前列腺癌居中国男性恶性肿瘤粗发病率第6位[3]。前列腺癌病因复杂,目前较为明确的危险因素仅包括年龄、种族和家族史,一级预防难以控制日益增长的前列腺癌疾病负担。局限性前列腺癌或区域性扩散的前列腺癌患者5年相对生存率可达100.0%,而存在远处转移的前列腺癌患者的5年相对生存率仅为30.2%[4]。因此,前列腺癌的早发现、早期诊断和早期治疗是改善患者预后和降低我国人群前列腺癌疾病负担的关键。

现有证据表明,前列腺癌筛查可降低筛查人群前列腺癌死亡率[5-6],但会造成过度诊断[7],导致过度治疗及医疗资源的浪费。如何进行前列腺癌筛查一直是医学领域十分重要又备受争议的话题。经济有效的筛查方案离不开科学证据的支持。系统总结循证医学证据的临床实践指南为临床医护乃至政府决策提供推荐和建议,直接影响整个行业的医疗实践。目前,西方发达国家的相关学会已经出版多部前列腺癌筛查指南[8-10]。中国抗癌协会于2017年发布了《前列腺癌筛查专家共识》[11],对于指导我国前列腺癌筛查的科学开展有着重要意义。然而,目前我国仍缺乏基于循证医学证据的前列腺癌筛查指南。临床实践指南的制定是一项严谨复杂的工程,美国医学会杂志就曾指出现行很多指南的制定过程仍存在问题[12]。本研究基于系统的文献检索,利用国际公认的实践指南报告标准与评估工具对前列腺癌筛查领域的相关指南进行评价,为后续我国前列腺癌筛查循证指南的制定提供参考。

资料与方法1. 文献检索:以前列腺癌、前列腺肿瘤、筛查、筛检、指南、共识、规范、标准、prostate cancer、prostate carcinoma、prostate tumor、screening、early detection、guideline等词为关键词系统检索中国知网、万方数据知识服务平台、中国生物医学文献服务系统、PubMed、Embase、Cochrane Library。并同时检索中国临床指南文库(China Guidelines Clearinghouse)和国际指南协作网(Guideline International Network)截至2020年3月31日前发表的所有中英文文献。并以美国预防服务工作组(U. S. Preventive Services Task Force)、美国癌症学会(American Cancer Society)、国际癌症研究署(International Agency for Research on Cancer)、澳大利亚癌症协会(Australia Cancer Council)、欧洲泌尿外科学会(European Association of Urology)等机构官网发布的指南作为补充。

2. 纳入和排除标准:对检索的文献进行筛选,纳入前列腺癌筛查领域所有相关的指南/共识,并符合美国医学研究所(Institute of Medicine)对指南的定义[13]。排除标准包括非中文或非英文指南、指南解读及综述类文献以及已更新的旧版指南。

3. 评价方法:采用开发指南研究和评估工具Ⅱ(Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation Ⅱ,AGREE Ⅱ)[14]和国际实践指南报告标准(Reporting Items for Practice Guidelines in Healthcare,RIGHT)[15]对纳入的指南分别进行方法学质量评价和报告质量评价。具体评价方法见文献[16]。AGREE Ⅱ评价根据6个领域(范围和目的、参与人员、严谨性、清晰性、应用性、独立性)的得分情况综合判断所评指南/共识是否值得推荐应用,基于AGREE Ⅱ得分将指南的推荐分为3个等级:A级即积极推荐(≥4个领域的分值≥50%)、B级即推荐(3个领域的分值≥50%)、C级即一定条件下推荐(≤2个领域的分值≥50%)。应用RIGHT对7个领域(基本信息、背景、证据、推荐意见、评审和质量保证、资金资助和利益冲突、其他方面)进行质量评价。项目组2名经过培训的评价人员独立进行文献信息提取和文献评价,评价过程中不进行交流,如有分歧则交由第三方专家进行讨论确定。

4. 统计学分析:采用Microsoft Excel 2018软件进行资料整理,AGREE Ⅱ评分和RIGHT报告率的整体情况采用百分比(%)、x±s来描述。采用组内相关系数(intra-class correlation coefficient,ICC)对2位评价人员的AGREE Ⅱ评分进行一致性评价。使用SPSS 21.0软件进行统计学分析。

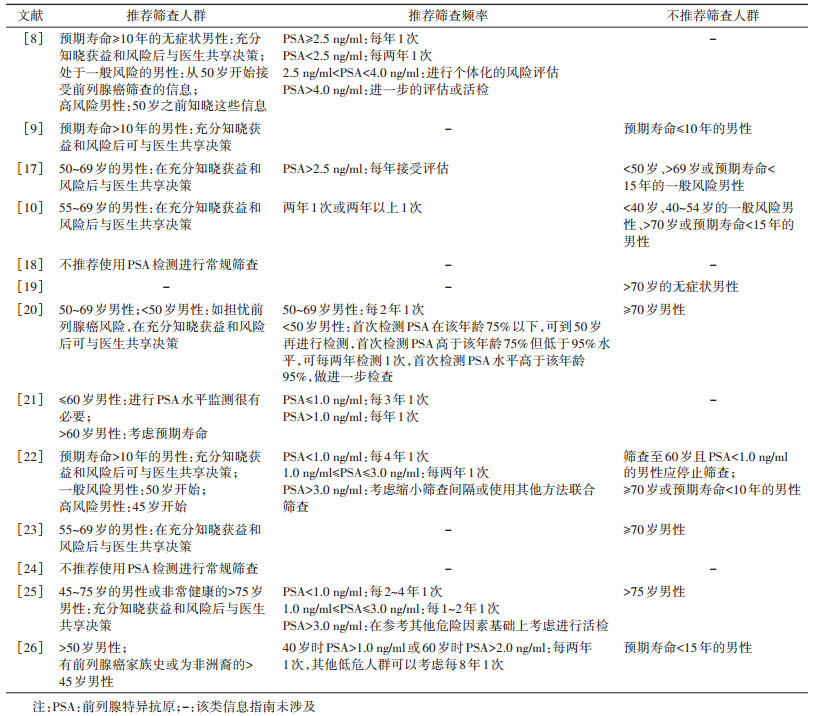

结果1. 基本情况:共检索到相关文献1 423篇。通过排除重复、不相关文献、非指南文献、指南解读/摘录、综述以及旧版指南,最终纳入13部指南[8-10, 17-26]。具体流程见图 1。纳入的13部指南均为英文文献,均为各国的相关协会发布。指南发布时间为2010-2020年,10部指南对所纳入的证据进行了分级评价。见表 1。大多数指南对基于前列腺特异抗原(prostate specific antigen,PSA)检测的前列腺癌筛查的适宜人群和筛查频率做出了推荐。各指南推荐意见总结见表 2。

|

| 图 1 前列腺癌筛查文献筛选流程 |

2. AGREE Ⅱ评价情况:2名评价人员的评价结果一致性较好(ICC=0.84,95%CI:0.79~0.88)。13部指南中,推荐等级为A级的有10部、B级的有2部、C级的有1部。纳入指南在6个领域的具体得分:①范围和目的:7部指南平均得分为74.2%±10.2%。每部指南得分均 > 50.0%,该领域问题主要集中于大多数指南在制定过程中未收集目标人群的观点。②参与人员:各指南在该领域得分普遍较低,仅1部指南得分 > 70.0%,5部指南得分 < 50%。③严谨性:平均得分为62.0%±17.4%,2部指南得分 > 80.0%,2部指南得分 < 50.0%。④清晰性:平均得分最高。各指南得分均 > 50.0%。⑤应用性:平均得分最低,7部指南平均得分为34.0%±10.8%,仅1部指南得分 > 50.0%。主要问题在于大部分指南未提供应用推荐建议的工具和潜在的相关资源。⑥独立性:指南之间得分差异较大,4部指南得分 > 80.0%,2部指南得分 < 50.0%。见表 3。

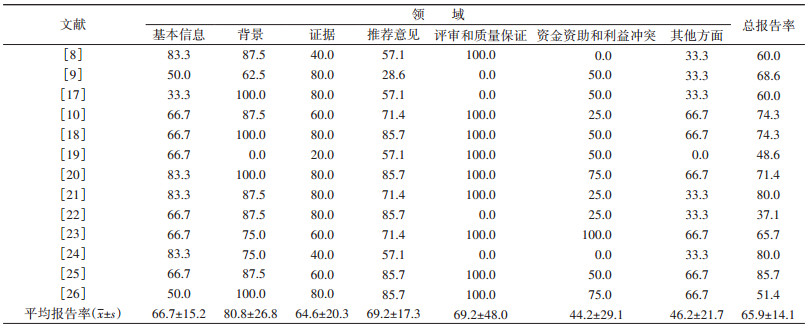

3. RIGHT评价情况:在所评价的7个领域中,证据的平均报告率最高(80.8%±26.8%),其他6个领域报告率均较低,资金资助和利益冲突的平均报告率最低(44.2%±29.1%)。纳入指南在7个领域的报告情况:①基本信息:仅3部指南列出了所涉及的缩略语和术语定义。②背景:7部指南未完整报告所有贡献者及作用。③证据:13部指南均未报告结局遴选和分类的方法,6部指南未报告系统评价的方法。④推荐意见:大多数指南未报告在形成推荐意见时是否考虑成本和资源利用(10部),是否考虑公平性、可行性和可接受性(10部)。⑤评审和质量保证:该领域各指南表现参差不齐,平均报告率为69.2%±48.0%。⑥资金资助和利益冲突:仅3部指南报告了资助者的作用,仅3部指南报告了利益冲突的管理方法。⑦其他方面:该领域整体得分较低,平均报告率为46.2%±21.7%,仅1部指南报告了局限性。见表 4。

前列腺癌筛查在西方国家已经开展了几十年,但如何开展前列腺癌筛查,如何平衡筛查带来的益处和问题仍是备受争议的话题。临床实践指南无疑是各个权威协会专业意见的精华和集合。本研究纳入的筛查指南集中在欧美地区,其中美国指南数量最多,这也与前列腺癌发病的地域性差异相符。本研究纳入的13部指南中,10部指南推荐等级为A级,整体质量较高,但根据AGREE Ⅱ和RIGHT工具,在一些条目上仍普遍存在问题。

本研究纳入的13部指南在应用性领域得分较低,大多数指南忽略了指南应用过程中潜在的促进因素、阻碍因素以及成本和资源问题[27]。根据相关系统综述报道,其他领域的临床实践指南也普遍存在该问题[28-30]。这可能是由于指南制定团队人员组成的限制,现有指南的参与人员多是临床医生、流行病学家、病理学家、医学影像学家等医疗行业从业者,部分指南邀请了患者参与制定。为使指南的推荐意见更符合实际情况,增强应用性,参与指南制定的人员结构应该更加多样化,必要时,应考虑邀请医疗保险行业人员以及政府部门人员参与指南的制定或者审阅。此外,指南制定者应考虑信息图表、线上教育视频等工具促进指南服务对象了解指南内容,方便指南的落地应用。

本研究纳入的指南报告质量问题集中在指南制定者角色以及利益冲突的报告不清晰。虽然该部分的报告可能受到文章发表版面的限制,但该部分是推广指南需考虑的重要因素,没有理由完全忽略该部分的报告。在协会官方网站发布的指南受益于在线的便捷性,可以详细呈现每个指南制定者的角色和利益冲突的评价管理。同时,在线发布的指南更新也较为方便。以欧洲泌尿外科学会的前列腺癌筛查指南为例[26],指南制作团队每年都会根据最新证据对一些推荐进行修改。同时,本研究纳入的大部分指南未列出指南中的缩写和术语定义,这可能取决于发表期刊的格式要求。本研究纳入的13部指南均未报告结局遴选和分类的方法。对于前列腺癌筛查指南来说,可能是因为可供选择的结局较少,多集中于前列腺癌的预后方面。

本研究应用AGREE Ⅱ和RIGHT工具对前列腺癌筛查指南的方法学质量和报告质量进行了较为全面的评价,可以为今后同类指南的制定和更新提供参考。然而,本研究也存在一定的局限性。由于本研究仅纳入中、英文指南,亚洲地区指南只纳入1部,可能存在其他语种指南未被纳入的情况。

基于PSA检测的前列腺癌筛查的有效性证据主要来自两个大型随机对照试验,即欧洲前列腺癌筛查随机研究(european randomized study of screening for prostate cancer,ERSPC)和美国前列腺癌、肺癌、结直肠癌和卵巢癌筛查试验(the prostate,lung,colorectal,and ovarian cancer screening trial,PLCO)。最近的一项研究公布了ERSPC的16年随访数据,结果表明筛查组前列腺癌死亡率较对照组降低20%(RR=0.80,95%CI:0.72~0.89)[31]。但这两个临床试验均存在对照组沾染等方法学缺陷,其中,PLCO对照组的沾染率更是超过了80%[32]。此外,考虑到参与者年龄和前列腺癌死亡高发年龄,PSA筛查的长期效果可能需要至少随访30年才能得到验证[33]。目前,仍无有力证据表明基于PSA检测的前列腺癌筛查的益处,前列腺癌死亡率是否可以完全反映筛查获益也有待商榷,但筛查造成的过度诊断和过度治疗十分明显[34-35]。因此,大多数指南在给出推荐意见时均会强调医生与患者共享决策(表 2)。中国抗癌协会于2017年发布了《前列腺癌筛查专家共识》[11],推荐身体状况良好且预期寿命 > 10年的男性开展基于PSA检测的前列腺癌筛查,同时也强调了医生需充分告知患者筛查的风险和获益。

国际上关于前列腺癌筛查的相关研究证据较多,为指南制定提供了良好基础,但是多为欧美国家的研究成果,我国目前尚无大规模人群研究验证前列腺癌筛查的有效性和卫生经济学效益。有研究表明,在PSA水平相同的情况下,中国人群的前列腺癌发病风险较西方人群更低[36],针对欧美人群的指南意见和决策工具可能并不适用于中国人群。因此,我国亟须本土研究探索适合国情的前列腺癌筛查策略。同时,我国前列腺癌筛查指南的制定也应基于我国人群的前列腺癌筛查研究和系统综述,在借鉴其他国家指南的同时充分考虑国情,参考AGREE Ⅱ和RIGHT工具,完善指南制定的各个环节。

利益冲突 所有作者均声明不存在利益冲突

| [1] |

Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2018:GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2018, 68(6): 394-424. DOI:10.3322/caac.21492 |

| [2] |

Culp MB, Soerjomataram I, Efstathiou JA, et al. Recent global patterns in prostate cancer incidence and mortality rates[J]. Eur Urol, 2020, 77(1): 38-52. DOI:10.1016/j.eururo.2019.08.005 |

| [3] |

郑荣寿, 孙可欣, 张思维, 等. 2015年中国恶性肿瘤流行情况分析[J]. 中华肿瘤杂志, 2019, 41(1): 19-28. Zheng RS, Sun KX, Zhang SW, et al. Report of cancer epidemiology in China, 2015[J]. Chin J Oncol, 2019, 41(1): 19-28. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-3766.2019.01.005 |

| [4] |

National Cancer Institute. Browse the SEER cancer statistics review 1975-2017[DB/OL]. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute, 2020. (2020-04-15)[2020-0505]. https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2017/browse_csr.php?sectionSEL=23&pageSEL=sect_23_table.082019.

|

| [5] |

Tsodikov A, Gulati R, Heijnsdijk EAM, et al. Reconciling the effects of screening on prostate cancer mortality in the ERSPC and PLCO trials[J]. Ann Intern Med, 2017, 167(7): 449-455. DOI:10.7326/m16-2586 |

| [6] |

Osses DF, Remmers S, Schröder FH, et al. Results of prostate cancer screening in a unique cohort at 19yr of follow-up[J]. Eur Urol, 2019, 75(3): 374-377. DOI:10.1016/j.eururo.2018.10.053 |

| [7] |

Fenton JJ, Weyrich MS, Durbin S, et al. Prostate-specific antigen-based screening for prostate cancer: evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force[J]. JAMA, 2018, 319(18): 1914-1931. DOI:10.1001/jama.2018.3712 |

| [8] |

Wolf AMD, Wender RC, Etzioni RB, et al. American Cancer Society guideline for the early detection of prostate cancer: update 2010[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2010, 60(2): 70-98. DOI:10.3322/caac.20066 |

| [9] |

Basch E, Oliver TK, Vickers A, et al. Screening for prostate cancer with prostate-specific antigen testing: American Society of Clinical Oncology provisional clinical opinion[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2012, 30(24): 3020-3025. DOI:10.1200/jco.2012.43.3441 |

| [10] |

American Urological Association. Prostate cancer: early detection guideline[DB/OL]. Linthicum: American Urological Association, 2018. (2018)[2020-04-05]. https://www.auanet.org/guidelines/prostate-cancer-earlydetection-guideline.

|

| [11] |

中国抗癌协会泌尿男生殖系统肿瘤专业委员会前列腺癌学组. 前列腺癌筛查专家共识[J]. 中华外科杂志, 2017, 55(5): 340-342. Prostate Cancer Working Group of Genitourinary Cancer Committee in Chinese Anti-Cancer Association. Consensus of prostate cancer screening[J]. Chin J Surg, 2017, 55(5): 340-342. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.05295815.2017.05.005 |

| [12] |

Shekelle PG. Clinical practice guidelines: what's next?[J]. JAMA, 2018, 320(8): 757-758. DOI:10.1001/jama.2018.9660 |

| [13] |

Institute of Medicine Committee to Advise the Public Health Service on Clinical Practice G. Clinical practice guidelines: Directions for a new program[M]. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 1990.

|

| [14] |

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. AGREE Ⅱ: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care[J]. CMAJ, 2010, 182(18): E839-842. DOI:10.1503/cmaj.090449 |

| [15] |

Chen YL, Yang KH, Marušić A, et al. A reporting tool for practice guidelines in health care: the RIGHT statement[J]. Ann Intern Med, 2017, 166(2): 128-132. DOI:10.7326/M16-1565 |

| [16] |

李江, 杨珂璐, 蔡依彤, 等. 全球乳腺癌筛查指南质量评价[J]. 中华流行病学杂志, 2021, 42(2): 219-226. Li J, Yang KL, Cai YT, et al. Quality assessment of global breast cancer screening guidelines[J]. Chin J Epidemiol, 2021, 42(2): 219-226. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.cn11233820200806-01032 |

| [17] |

Qaseem A, Barry MJ, Denberg TD, et al. Screening for prostate cancer: a guidance statement from the clinical guidelines committee of the American College of Physicians[J]. Ann Intern Med, 2013, 158(10): 761-769. DOI:10.7326/0003-4819-158-10-201305210-00633 |

| [18] |

Bell N, Gorber SC, Shane A, et al. Recommendations on screening for prostate cancer with the prostate-specific antigen test[J]. CMAJ, 2014, 186(16): 1225-1234. DOI:10.1503/cmaj.140703 |

| [19] |

Parker C, Gillessen S, Heidenreich A, et al. Cancer of the prostate: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up[J]. Ann Oncol, 2015, 26(Suppl 5): v69-77. DOI:10.1093/annonc/mdv222 |

| [20] |

Prostate Cancer Foundation of Australia and Cancer Council Australia. PSA testing and early management of test-detected prostate cancer expert advisory panel[DB/OL]. Sydney: Prostate Cancer Foundation of Australia and Cancer Council Australia (Australia), 2016. (2016-01-14)[2020-04-05]. https://wiki.cancer.org.au/australia/Guidelines:PSA_Testing.

|

| [21] |

Kakehi Y, Sugimoto M, Taoka R. Evidenced-based clinical practice guideline for prostate cancer (summary: Japanese Urological Association, 2016 edition)[J]. Int J Urol, 2017, 24(9): 648-666. DOI:10.1111/iju.13380 |

| [22] |

Rendon RA, Mason RJ, Marzouk K, et al. Canadian Urological Association recommendations on prostate cancer screening and early diagnosis[J]. Can Urol Assoc J, 2017, 11(10): 298-309. DOI:10.5489/cuaj.4888 |

| [23] |

Grossman DC, Curry SJ, Owens DK, et al. Screening for prostate cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement[J]. JAMA, 2018, 319(18): 1901-1913. DOI:10.1001/jama.2018.3710 |

| [24] |

The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Guidelines for preventive activities in general practice[M]. 9th ed. East Melbourne, Victoria: RACGP, 2018.

|

| [25] |

National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Prostate cancer early detection[DB/OL]. National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 2019. (2019-05-31)[2020-04-02]. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx#detection.

|

| [26] |

Mottet N, Cornford P, van den Bergh RCN, et al. EAU-EANM-ESTRO-ESUR-SIOG guidelines on prostate cancer 2020[DB/OL]. Arnhem: EAU Guidelines Office (The Netherlands), 2020.[2020-04-04]. https://uroweb.org/guideline/prostate-cancer.

|

| [27] |

Alonso-Coello P, Irfan A, Solà I, et al. The quality of clinical practice guidelines over the last two decades: a systematic review of guideline appraisal studies[J]. Qual Saf Health Care, 2010, 19(6): e58. DOI:10.1136/qshc.2010.042077 |

| [28] |

Lin I, Wiles LK, Waller R, et al. Poor overall quality of clinical practice guidelines for musculoskeletal pain: a systematic review[J]. Br J Sports Med, 2018, 52(5): 337-343. DOI:10.1136/bjsports-2017-098375 |

| [29] |

Pincus D, Kuhn JE, Sheth U, et al. A systematic review and appraisal of clinical practice guidelines for musculoskeletal soft tissue injuries and conditions[J]. Am J Sports Med, 2017, 45(6): 1458-1464. DOI:10.1177/0363546516667903 |

| [30] |

Isaac A, Saginur M, Hartling L, et al. Quality of reporting and evidence in American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines[J]. Pediatrics, 2013, 131(4): 732-738. DOI:10.1542/peds.2012-2027 |

| [31] |

Hugosson J, Roobol MJ, Månsson M, et al. A 16-yr follow-up of the European randomized study of screening for prostate cancer[J]. Eur Urol, 2019, 76(1): 43-51. DOI:10.1016/j.eururo.2019.02.009 |

| [32] |

Shoag JE, Mittal S, Hu JC. Reevaluating PSA testing rates in the PLCO trial[J]. N Engl J Med, 2016, 374(18): 1795-1796. DOI:10.1056/NEJMc1515131 |

| [33] |

Shoag JE, Nyame YA, Gulati R, et al. Reconsidering the trade-offs of prostate cancer screening[J]. N Engl J Med, 2020, 382(25): 2465-2468. DOI:10.1056/NEJMsb2000250 |

| [34] |

Welch HG, Albertsen PC. Prostate cancer diagnosis and treatment after the introduction of prostate-specific antigen screening: 1986-2005[J]. J Natl Cancer Inst, 2009, 101(19): 1325-1329. DOI:10.1093/jnci/djp278 |

| [35] |

Welch HG, Albertsen PC. Reconsidering prostate cancer mortality-the future of PSA screening[J]. N Engl J Med, 2020, 382(16): 1557-1563. DOI:10.1056/NEJMms1914228 |

| [36] |

Chen R, Sjoberg DD, Huang YR, et al. Prostate specific antigen and prostate cancer in Chinese men undergoing initial prostate biopsies compared with western cohorts[J]. J Urol, 2017, 197(1): 90-96. DOI:10.1016/j.juro.2016.08.103 |

2021, Vol. 42

2021, Vol. 42