文章信息

- 覃凤芝, 袁满琼, 周鼒, 方亚.

- Qin Fengzhi, Yuan Manqiong, Zhou Zi, Fang Ya

- 童年期不良经历与成年人常见慢性非传染性疾病关系的研究进展

- Progress in research of association of adverse childhood experiences with prevalence of common chronic diseases in adulthood

- 中华流行病学杂志, 2020, 41(11): 1933-1937

- Chinese Journal of Epidemiology, 2020, 41(11): 1933-1937

- http://dx.doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn112338-20191104-00783

-

文章历史

收稿日期: 2019-11-04

2. 厦门大学公共事务学院 361005

2. School of Public Affairs, Xiamen University, Xiamen 361005, China

个体的生命早期经历,对于成年期的身体功能、认知功能和情绪发展具有重要作用[1]。WHO指出,童年期不良经历(adverse childhood experiences,ACE)指在儿童生命早期发生的最密集和频率较高的,且为压力来源的一系列事件[2]。美国CDC明确了ACE的具体范围,指出其为发生于18岁以前所有类型的虐待、忽视和其他潜在的创伤性经历[3]。各国调查中,超过25%的人群曾有过≥1项ACE,美国高达61%[4-7]。

ACE在生命历程中的不良健康效应受到越来越多关注,很多研究发现它与不良健康行为以及疾病的发生呈正相关,如吸毒、自杀、传染性疾病和慢性非传染性疾病(慢性病)等[6, 8-10]。其中,慢性病患病率高、并发症数目多和疾病负担大,是目前很多学者研究的方向[11-12]。高血压、糖尿病、抑郁症和痴呆症是我国常见的和负担比较重的慢性病;我国2017年致伤残疾病病因统计中,肌肉骨骼相关疾病位居第一[12]。研究ACE与慢性病之间的关系对于慢性病防控具有重要意义。本文首先简要介绍ACE的测量工具和相关指标,其次对常见的慢性病(高血压、糖尿病、关节炎、痴呆症和抑郁症)与ACE之间的关系和可能的影响机制进行综述,为我国的相关研究和一级预防措施的选取提供参考。

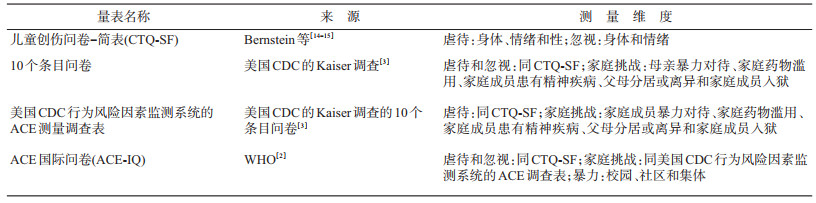

1. ACE的测量工具:目前常用测量ACE的量表主要有4种(表 1)。CTQ-SF为儿童创伤问卷简化后用于测量童年期暴力对待的量表[13-15];10个条目问卷(10-item questionnaire)为美国CDC的Kaiser Permanente(Kaiser)调查所用的调查表,其在CTQ-SF 5个维度的基础上加入家庭挑战[3, 16];美国CDC行为风险因素监测系统用于测量ACE的工具为基于Kaiser调查的10个条目问卷研制的包含虐待和家庭挑战的调查表[3, 16];ACE-IQ为WHO在基于10个条目问卷的维度加入了校园暴力、社区暴力和集体暴力3个方面,并用于各个国家ACE的测量的量表[2]。

然而,很多研究并未严格按照这4个量表的维度和条目来测量ACE。有些研究缺少如性虐待、社区暴力等维度[17-19]。有些研究在10个条目问卷之上加上童年期疾病和经济状况[20-21];而有些对于家庭挑战相关的ACE条目,在包含父母之间的暴力对待和父母对子女的暴力对待情况这2个条目之上,加入潜在的使精神受创伤的条目(如意外事故、身体受到攻击、目睹暴力情况或谋杀或致死亡事故、性虐待、经历战争或者加入过战斗)[22]。这些研究均表明所加入的ACE指标与相应的不良健康结局呈正相关关系,提示目前量表包括的条目,在使用的时候可能需要根据不同的研究目的进行适当调整,如纳入更多和更全面的童年期社会决定因素(社会经济状况、社会支持等)[16]。虽然目前的ACE量表中的条目可能不尽完备,但也有研究指出它不必要囊括所有ACE条目,因为其目前已给我们提供了比较完整的预防方向[21]。

2. ACE与成年人慢性病关系:在美国1995-1997年的Kaiser调查之后,ACE与健康效应的关系受到国内外学者的关注。本文主要对ACE和5种成年人比较常见的慢性病(高血压、糖尿病、关节炎、痴呆症和抑郁症)的关系进行综述。

(1)高血压:据WHO报告,全世界有11.3亿人患有高血压[23],我国2012-2015年高血压调查结果显示,成年人高血压患病率为23.2%,患前期高血压人群占41.3%[24]。肥胖、吸烟和饮酒是高血压发病的危险因素,同时也是ACE的不良后果[8, 25-26],提示ACE和高血压患病可能存在关联。2009-2011年美国的行为风险因素监测系统数据显示,经历过ACE的人群较未经历过的人群高血压患病风险增加4%,并且两者存在剂量-反应关系(趋势检验P < 0.001)[27]。2016年德国的一项横截面调查结果也显示类似关联[28]。ACE与高血压的关联性受性别、年龄和社会经济地位影响。一项研究对美国11~17岁人群进行14年的4期随访数据进行分析,发现曾经目睹枪击暴力事件的成年男性和曾为枪击事件受害者的女性,高血压患病风险增加(OR=1.44,95%CI:1.01~2.05;OR=1.73,95%CI:1.04~2.85)[29]。有研究对居住在美国的5~16岁的欧洲人和非洲人进行23年16次随访研究,发现ACE与年龄对于血压值有交互效应,即ACE与血压值的效应随着年龄增长而增加[30]。另一项调查显示ACE与高血压患病的关联性在 < 40岁人群中较高[27]。美国俄勒冈州的一项研究指出两者在低收入成年人群中无关联[31]。但在国内研究中,一项队列调查指出童年期经历过1959-1961年大饥荒的人群较1962年之后出生的人群高血压发病风险低[32]。

(2)糖尿病:2015年全球20~79岁的糖尿病患者约为4.15亿人,2013年我国全国调查的糖尿病患病率为10.9%,前期糖尿病为35.7%,糖尿病患病形势严峻[33-34]。国外(尤其是美国)较多研究指出ACE与糖尿病患病有关联。2009-2011年美国的行为风险因素监测系统数据指出ACE与糖尿病患病有关,并且每增加一类ACE,人群的糖尿病平均患病风险增高10%(OR=1.10,95%CI:1.06~1.14),有3类ACE的人群糖尿病患病风险增加38%[27]。2015-2017年的监测数据也指出经历过≥4类的ACE较未经历的成年人群的糖尿病患病风险平均增加40%(95%CI:20%~50%)[35]。沙特阿拉伯的一项横截面调查显示童年期性虐待与糖尿病患病呈正相关[36]。两者的关联性与ACE类别和社会经济地位有关。美国的一项研究指出有性虐待经历的人群糖尿病患病风险最高(OR=1.57,95%CI:1.24~1.99)[37]。而一篇系统综述表明经历过童年期忽视的人群2型糖尿病患病风险最高(OR=1.92,95%CI:1.42~2.57)[38]。美国俄勒冈州的一项研究指出ACE和糖尿病患病在低收入成年人群中无关联[31]。此外,ACE可间接影响糖尿病发病。一项研究指出ACE通过抑郁间接导致糖尿病发病风险增加[39]。国内研究中,一项队列研究指出我国童年期经历过1959-1961年饥荒的人群较1962年之后出生的人群糖尿病患病风险增加[40]。

(3)关节炎:作为致残率较高的一类疾病,关节炎的患病率和疾病负担也不可忽视。据调查,2010-2012年美国的成年人关节炎患病率为22.7%,预测至2040年为25.9%,因关节炎而活动受限人群达到3 460万人[41]。2011年我国≥45岁人群的有症状性骨关节炎患病率为8.1%[42]。ACE引起的免疫系统功能改变可能与关节炎的发病机制有关。目前研究两者关系的文献主要在国外,研究类型为回顾性研究居多,较多研究指出两者具有正相关关系。巴西的一项病例对照研究发现类风湿性关节炎患病风险在青年和中年人群中与ACE呈正相关关系[43]。ACE与关节炎的关联性受性别和ACE类别的影响。德国的一项研究则指出成年男性的类风湿性关节炎患病仅与情绪忽视有关联,而女性的类风湿性关节炎患病还与情绪虐待和身体虐待有关,但情绪虐待的患病风险最高(OR=3.2,95%CI:1.5~6.6)[44]。WHO对10个国家的≥21岁人群进行精神健康的回顾性调查,发现童年期经历了性虐待的成年人患关节炎风险最高(HR=1.64,95%CI:1.28~2.09)[45]。加拿大的一项回顾性调查指出,童年期身体虐待与骨关节炎患病存在剂量-反应效应,经历过严重身体虐待的人群较未有此经历的人群骨关节炎患病风险增高100%(20%~250%)[46]。

(4)痴呆症:痴呆症是全球备受关注的公共卫生问题,世界阿尔茨海默报告指出2018年全世界痴呆症患者人数为5 000万[47],近20年我国中老年人的患病率和发病率持续增长,患病形势严峻[48-49]。ACE作为一种慢性压力,对身体的作用机制可能与痴呆症的发病机制存在关联[50]。但是目前国内外关于ACE与痴呆症的研究较少,并且结果不太一致。一项研究对澳大利亚≥60岁的农村和城镇居民横截面调查数据进行分析,发现CTQ-SF分数越高,痴呆患病风险越大(OR=1.70,95%CI:1.17~2.54),其中作为最常见的痴呆症类型,AD的患病风险增加[51]。一项芬兰东部的队列研究发现童年期压力性事件会增加老年期患痴呆风险(OR=1.86,95%CI:1.01~3.39),但不会增加患AD风险(OR=1.75,95%CI:0.85~3.59)[52]。

(5)抑郁症:ACE被视作一种创伤性事件,很多研究认为其影响个体的心理健康,并可能进一步损害身体健康。抑郁是常见的心理疾病,全球有超过1.21亿人受抑郁症的困扰[53]。目前国内外学者较关注ACE与成年期抑郁症的关系。国外一项Meta分析指出ACE与成年期抑郁症相关,并且有剂量-反应关系,且不同类别ACE的患病风险有差异,其中童年期经历了情绪虐待的患病风险最高(OR=3.06,95%CI:2.43~3.85)[18]。但有研究发现童年期经历了身体虐待、性虐待或情感忽视的成年人得抑郁症的风险较高[54-55]。这种类别差异可能受性别和年龄影响。国内一项研究指出女性经历童年期接触性性虐待率高于男性,而非接触性性虐待率低于男性[56]。美国一项研究指出14岁时男性暴露于非语言情绪虐待为成年期预测抑郁的重要因子,而14岁女性则为同伴情绪虐待[57]。此外,芬兰有研究对ACE和抑郁的间接效应进行检验,发现其他人的消极态度具有不完全中介效应[58]。爱尔兰一项研究也提到,经历过ACE人群若有更多的社会支持,能够降低抑郁症患病风险[59]。

3. ACE与慢性病相关的可能机制:目前ACE影响成年期慢性病的发生机制可基于累积不平等理论(Cumulative Inequality)[60]:首先,ACE的发生会增加个体在未来暴露于慢性病危险因素的风险,如低学历、低收入和采取不良的行为(吸烟、饮酒)和生活方式等[61-62],这些危险因素及其所导致的后果在个体生命历程中不断增加和累积,间接导致个体间疾病与健康轨迹的差异。但若个体因ACE而过早死亡,则这种差异则会因为人群的选择偏倚而降低、消失甚至逆转[60]。

其次,ACE的发生也可能直接损害生理功能。国内外有研究对相关的生物标志物进行检测,并对动物模型进行研究,认为ACE对慢性病影响可能有以下的生物学机制:①大脑结构和功能改变:ACE对大脑结构和功能产生负面影响,如胼胝体和海马体体积缩小,双侧杏仁核、海马旁回、右脑岛和右颞上回等的过度活化,导致情感、认知、学习和记忆功能改变[62-65]。②影响神经内分泌功能:ACE发生之后,慢性激活下丘脑-垂体-肾上腺轴,导致糖皮质激素过量释放,损伤个体的心血管功能和大脑功能[61, 66]。③免疫系统:ACE为一种慢性压力,对机体进行长期刺激,增加免疫系统对于负性事件刺激的敏感性,白介素-6、C反应蛋白和ET-1等炎症因子持续释放,增加心血管疾病患病风险[63, 67]。④表观遗传学:ACE增加涉及神经精神疾病、心血管疾病、肥胖和多种癌症的基因区域的甲基化[62, 68-69]。但具体的机制未明确。

综上所述,近20年来国际上较多研究关注ACE与常见慢性病的关系,但国内此类研究仍较少。多数ACE类别与成年人慢性病患病呈正相关,但ACE类别对慢性病的影响及其效应大小在各研究中存在差异,这可能与地区、性别、调查年龄、ACE发生的年龄以及社会经济地位有关。此外,儿童期有大饥荒经历的人群,高血压患病风险反而较未有此经历的人群低。在机制研究上,国外较多学者研究ACE与慢性病的生物学机制,如采集和研究人群脑部影像、生物标志物(生化、基因等)等,而国内鲜少有此类研究。由此,我国需要更多的研究明确ACE各类测量指标效应以及相应的敏感年龄,并且探索ACE与慢性病之间的关联和相关机制。此外,在今后研究设计中,需要合理选择ACE的测量指标,增加研究结果的可比性,为我国慢性病一级预防措施的提出提供参考依据[70-71]。

利益冲突 所有作者均声明不存在利益冲突

| [1] |

Marmot M, Allen J, Bell R, et al. WHO European review of social determinants of health and the health divide[J]. Lancet, 2012, 380(9846): 1011-1029. DOI:10.1016/s0140-6736(12)61228-8 |

| [2] |

World Health Organization. Adverse Childhood Experiences International Questionnaire. In Adverse Childhood Experiences International Questionnaire (ACE-IQ)[DB/OL]: Geneva: WHO, 2018.[2020-09-17]. https://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/activities/adverse_childhood_experiences/en/.

|

| [3] |

Injury Center. Preventing Adverse Childhood Experiences[DB/OL]. American Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.[2020-09-17]. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/acestudy/about.html.

|

| [4] |

Merrick MT, Ford DC, Ports KA, et al. Prevalence of adverse childhood experiences from the 2011-2014 behavioral risk factor surveillance system in 23 states[J]. JAMA Pediatr, 2018, 172(11): 1038-1044. DOI:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.2537 |

| [5] |

Björkenstam E, Hjern A, Vinnerljung B. Adverse childhood experiences and disability pension in early midlife:results from a Swedish National Cohort Study[J]. Eur J Public Health, 2017, 27(3): 472-477. DOI:10.1093/eurpub/ckw233 |

| [6] |

Bellis MA, Hughes K, Leckenby N, et al. Measuring mortality and the burden of adult disease associated with adverse childhood experiences in England:a national survey[J]. J Public Health (Oxf), 2015, 37(3): 445-454. DOI:10.1093/pubmed/fdu065 |

| [7] |

Yang L, Hu YY, Silventoinen K, et al. Childhood adversity and depressive symptoms among middle-aged and older Chinese:results from China health and retirement longitudinal study[J]. Aging Mental Health, 2019, 24(6): 923-931. DOI:10.1080/13607863.2019.1569589 |

| [8] |

Hughes K, Bellis MA, Hardcastle KA, et al. The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health:a systematic review and Meta-analysis[J]. Lancet Public Health, 2017, 2(8): e356-366. DOI:10.1016/s2468-2667(17)30118-4 |

| [9] |

龚纯, 方姣, 单杰, 等. 童年期虐待经历与青春期抑郁症状的前瞻性关联[J]. 中华流行病学杂志, 2018, 39(9): 1184-1187. Gong C, Fang J, Shan J, et al. Prospective association between childhood abuse experiences and depressive symptoms in adolescence[J]. Chin J Epidemiol, 2018, 39(9): 1184-1187. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2018.09.008 |

| [10] |

万宇辉, 刘婉, 孙莹, 等. 童年期虐待的不同形式与中学生自杀行为关联性研究[J]. 中华流行病学杂志, 2016, 37(4): 506-511. Wan YH, Liu W, Sun Y, et al. Relationships between various forms of childhood abuse and suicidal behaviors among middle school students[J]. Chin J Epidemiol, 2016, 37(4): 506-511. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2016.04.013 |

| [11] |

GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017:a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017[J]. Lancet, 2018, 392(10159): 1789-1858. DOI:10.1016/s0140-6736(18)32279-7 |

| [12] |

Zhou MG, Wang HD, Zeng XY, et al. Mortality, morbidity, and risk factors in China and its provinces, 1990-2017:a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017[J]. Lancet, 2019, 394(10204): 1145-1158. DOI:10.1016/s0140-6736(19)30427-1 |

| [13] |

Slavich GM, Shields GS. Assessing lifetime stress exposure using the stress and adversity inventory for adults (Adult STRAIN):an overview and initial validation[J]. Psychosom Med, 2018, 80(1): 17-27. DOI:10.1097/psy.0000000000000534 |

| [14] |

Bernstein DP, Fink L, Handelsman L, et al. Initial reliability and validity of a new retrospective measure of child abuse and neglect[J]. Am J Psychiatry, 1994, 151(8): 1132-1136. DOI:10.1176/ajp.151.8.1132 |

| [15] |

Bernstein DP, Stein JA, Newcomb MD, et al. Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire[J]. Child Abuse Negl, 2003, 27(2): 169-190. DOI:10.1016/S0145-2134(02)00541-0 |

| [16] |

McEwen CA, Gregerson SF. A critical assessment of the adverse childhood experiences study at 20 years[J]. Am J Prev Med, 2019, 56(6): 790-794. DOI:10.1016/j.amepre.2018.10.016 |

| [17] |

Hunt TKA, Slack KS, Berger LM. Adverse childhood experiences and behavioral problems in middle childhood[J]. Child Abuse Negl, 2017, 67: 391-402. DOI:10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.11.005 |

| [18] |

Ege MA, Messias E, Thapa PB, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and geriatric depression:results from the 2010 BRFSS[J]. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry, 2015, 23(1): 110-114. DOI:10.1016/j.jagp.2014.08.014 |

| [19] |

Poletti S, Aggio V, Brioschi S, et al. Multidimensional cognitive impairment in unipolar and bipolar depression and the moderator effect of adverse childhood experiences[J]. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci, 2017, 71(5): 309-317. DOI:10.1111/pcn.12497 |

| [20] |

Kessler RC, McLaughlin KA, Green JG, et al. Childhood adversities and adult psychopathology in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys[J]. Br J Psychiatry, 2010, 197(5): 378-385. DOI:10.1192/bjp.bp.110.080499 |

| [21] |

Finkelhor D, Shattuck A, Turner H, et al. Improving the adverse childhood experiences study scale[J]. JAMA Pediatr, 2013, 167(1): 70-75. DOI:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.420 |

| [22] |

Ajdacic-Gross V, Mutsch M, Rodgers S, et al. A step beyond the hygiene hypothesis-immune-mediated classes determined in a population-based study[J]. BMC Med, 2019, 17: 75. DOI:10.1186/s12916-019-1311-z |

| [23] |

WHO. Hypertension[DB/OL]. 2019. https://www.who.int/health-topics/hypertension/.

|

| [24] |

Wang ZW, Chen Z, Zhang LF, et al. Status of hypertension in China:results from the China hypertension survey, 2012-2015[J]. Circulation, 2018, 137(22): 2344-2356. DOI:10.1161/circulationaha.117.032380 |

| [25] |

Anda RF, Croft JB, Felitti VJ, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and smoking during adolescence and adulthood[J]. JAMA, 1999, 282(17): 1652-1658. DOI:10.1001/jama.282.17.1652 |

| [26] |

王增武, 杨瑛, 王文, 等. 我国高血压流行新特征——中国高血压调查的亮点和启示[J]. 中国循环杂志, 2018, 33(10): 937-939. Wang ZW, Yang Y, Wang W, et al. New characteristics of hypertension in China:Highlights and enlightenment of China's hypertension survey[J]. Chin Circulat J, 2018, 33(10): 937-939. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1000-3614.2018.10.001 |

| [27] |

Kreatsoulas C, Fleegler EW, Kubzansky LD, et al. Young adults and adverse childhood events:a potent measure of cardiovascular risk[J]. Am J Med, 2019, 132(5): 605-613. DOI:10.1016/j.amjmed.2018.12.022 |

| [28] |

Clemens V, Huber-Lang M, Plener PL, et al. Association of child maltreatment subtypes and long-term physical health in a German representative sample[J]. Eur J Psychotraumatol, 2018, 9(1): 1510278. DOI:10.1080/20008198.2018.1510278 |

| [29] |

Ford JL, Browning CR. Effects of exposure to violence with a weapon during adolescence on adult hypertension[J]. Ann Epidemiol, 2014, 24(3): 193-198. DOI:10.1016/j.annepidem.2013.12.004 |

| [30] |

Su S, Wang XL, Pollock JS, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and blood pressure trajectories from childhood to young adulthood:the Georgia stress and Heart study[J]. Circulation, 2015, 131(19): 1674-1681. DOI:10.1161/circulationaha.114.013104 |

| [31] |

Allen H, Wright BJ, Vartanian K, et al. Examining the prevalence of adverse childhood experiences and associated cardiovascular disease risk factors among low-income uninsured adults[J]. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes, 2019, 12(9): e004391. DOI:10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.117.004391 |

| [32] |

Zhao RC, Duan XY, Wu Y, et al. Association of exposure to Chinese famine in early life with the incidence of hypertension in adulthood:A 22-year cohort study[J]. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis, 2019, 29(11): 1237-1244. DOI:10.1016/j.numecd.2019.07.008 |

| [33] |

Ogurtsova K, da Rocha Fernandes JD, Huang Y, et al. IDF Diabetes Atlas:Global estimates for the prevalence of diabetes for 2015 and 2040[J]. Diabetes Res Clin Pract, 2017, 128: 40-50. DOI:10.1016/j.diabres.2017.03.024 |

| [34] |

Wang LM, Gao P, Zhang M, et al. Prevalence and ethnic pattern of diabetes and prediabetes in China in 2013[J]. JAMA, 2017, 317(24): 2515-2523. DOI:10.1001/jama.2017.7596 |

| [35] |

Merrick MT, Ford DC, Ports KA, et al. Vital signs:estimated proportion of adult health problems attributable to adverse childhood experiences and implications for prevention-25 States, 2015-2017[J]. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 2019, 68(44): 999-1005. DOI:10.15585/mmwr.mm6844e1 |

| [36] |

Almuneef M. Long term consequences of child sexual abuse in Saudi Arabia:A report from national study[J]. Child Abuse Negl, 2019, 103967. DOI:10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.03.003 |

| [37] |

Campbell JA, Farmer GC, Nguyen-Rodriguez S, et al. Relationship between individual categories of adverse childhood experience and diabetes in adulthood in a sample of US adults:Does it differ by gender?[J]. J Diabetes Complications, 2018, 32(2): 139-143. DOI:10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2017.11.005 |

| [38] |

Huang H, Yan PP, Shan ZL, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and risk of type 2 diabetes:A systematic review and Meta-analysis[J]. Metabolism, 2015, 64(11): 1408-1418. DOI:10.1016/j.metabol.2015.08.019 |

| [39] |

Deschênes SS, Graham E, Kivimäki M, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and the risk of diabetes:examining the roles of depressive symptoms and cardiometabolic dysregulations in the whitehall Ⅱ cohort study[J]. Diabetes Care, 2018, 41(10): 2120-2126. DOI:10.2337/dc18-0932 |

| [40] |

Wang J, Li YR, Han X, et al. Exposure to the Chinese famine in childhood increases type 2 diabetes risk in adults[J]. J Nutr, 2016, 146(11): 2289-2295. DOI:10.3945/jn.116.234575 |

| [41] |

Hootman JM, Helmick CG, Barbour KE, et al. Updated projected prevalence of self-reported doctor-diagnosed arthritis and arthritis-attributable activity limitation among US adults, 2015-2040[J]. Arthritis Rheumatol, 2016, 68(7): 1582-1587. DOI:10.1002/art.39692 |

| [42] |

Tang X, Wang SF, Zhan SY, et al. The prevalence of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis in China:results from the China health and retirement longitudinal study[J]. Arthritis Rheumatol, 2016, 68(3): 648-653. DOI:10.1002/art.39465 |

| [43] |

Luiz APL, Antico HDA, Skare TL, et al. Adverse childhood experience and rheumatic diseases[J]. Clin Rheumatol, 2018, 37(10): 2863-2867. DOI:10.1007/s10067-018-4200-5 |

| [44] |

Spitzer C, Wegert S, Wollenhaupt J, et al. Gender-specific association between childhood trauma and rheumatoid arthritis:a case-control study[J]. J Psychosom Res, 2013, 74(4): 296-300. DOI:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2012.10.007 |

| [45] |

von Korff M, Alonso J, Ormel J, et al. Childhood psychosocial stressors and adult onset arthritis:broad spectrum risk factors and allostatic load[J]. Pain, 2009, 143(1/2): 76-83. DOI:10.1016/j.pain.2009.01.034 |

| [46] |

Badley EM, Shields M, O'Donnell S, et al. Childhood maltreatment as a risk factor for arthritis:findings from a population-based survey of Canadian adults[J]. Arthrit Care Res, 2018, 71(10): 1366-1371. DOI:10.1002/acr.23776 |

| [47] |

ADI. World Alzheimer Report 2018[R]. London: Alzheimer's Disease International, 2018.

|

| [48] |

Chan KY, Wang W, Wu JJ, et al. Epidemiology of Alzheimer's disease and other forms of dementia in China, 1990-2010:a systematic review and analysis[J]. Lancet, 2013, 381(9882): 2016-2023. DOI:10.1016/s0140-6736(13)60221-4 |

| [49] |

Xu JF, Zhang YQ, Qiu CXX, et al. Global and regional economic costs of dementia:a systematic review[J]. Lancet, 2017, 390(Suppl 4): S47. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)33185-9 |

| [50] |

Kempuraj D, Mentor S, Thangavel R, et al. Mast cells in stress, pain, blood-brain barrier, neuroinflammation and alzheimer's disease[J]. Front Cell Neurosci, 2019, 13: 54. DOI:10.3389/fncel.2019.00054 |

| [51] |

Radford K, Delbaere K, Draper B, et al. Childhood stress and adversity is associated with late-life dementia in aboriginal Australians[J]. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry, 2017, 25(10): 1097-1106. DOI:10.1016/j.jagp.2017.05.008 |

| [52] |

Donley GAR, Lönnroos E, Tuomainen TP, et al. Association of childhood stress with late-life dementia and Alzheimer's disease:the KIHD study[J]. Eur J Public Health, 2018, 28(6): 1069-1073. DOI:10.1093/eurpub/cky134 |

| [53] |

Moussavi S, Chatterji S, Verdes E, et al. Depression, chronic diseases, and decrements in health:results from the World Health surveys[J]. Lancet, 2007, 370(9590): 851-858. DOI:10.1016/s0140-6736(07)61415-9 |

| [54] |

Norman RE, Byambaa M, De R, et al. The long-term health consequences of child physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect:a systematic review and Meta-analysis[J]. PLoS Med, 2012, 9(11): e1001349. DOI:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001349 |

| [55] |

许成岗, 焦志安, 曹文胜, 等. 抑郁障碍与童年期被虐待经历的关系[J]. 精神医学杂志, 2007, 20(3): 147-149. Xu CG, Jiao ZA, Cao WS, et al. Relationship of depressive disorder and childhood maltreated experiences[J]. J Psychiat, 2007, 20(3): 147-149. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1009-7201.2007.03.008 |

| [56] |

苏普玉, 陶芳标, 曹秀菁, 等. 1 386名大学生童年期性虐待与不良心理行为的相关性研究[J]. 中华流行病学杂志, 2008, 29(1): 94-95. Su PY, Tao FB, Cao XJ, et al. Study on the relationship between sexual abuse in childhood and psychiatric disorder, risky behaviors in youthhood among 1 386 medicos[J]. Chin J Epidemiol, 2008, 29(1): 94-95. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:0254-6450.2008.01.025 |

| [57] |

Khan A, Mccormack HC, Bolger EA, et al. Childhood maltreatment, depression, and suicidal ideation:critical importance of parental and peer emotional abuse during developmental sensitive periods in males and females[J]. Front Psychiatry, 2015, 6: 42. DOI:10.3389/fpsyt.2015.00042 |

| [58] |

Salokangas RKR, From T, Luutonen S, et al. Adverse childhood experiences leads to perceived negative attitude of others and the effect of adverse childhood experiences on depression in adulthood is mediated via negative attitude of others[J]. Eur Psychiatry, 2018, 54: 27-34. DOI:10.1016/j.eurpsy.2018.06.011 |

| [59] |

von Cheong E, Sinnott C, Dahly D, et al. Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and later-life depression:perceived social support as a potential protective factor[J]. BMJ Open, 2017, 7(9): e013228. DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013228 |

| [60] |

Ferraro KF, Shippee TP. Aging and cumulative inequality:how does inequality get under the skin?[J]. Gerontologist, 2009, 49(3): 333-343. DOI:10.1093/geront/gnp034 |

| [61] |

Su SY, Jimenez MP, Roberts CTF, et al. The role of adverse childhood experiences in cardiovascular disease risk:a review with emphasis on plausible mechanisms[J]. Curr Cardiol Rep, 2015, 17(10): 88. DOI:10.1007/s11886-015-0645-1 |

| [62] |

Suglia SF, Koenen KC, Boynton-Jarrett R, et al. Childhood and adolescent adversity and cardiometabolic outcomes:a scientific statement from the american heart association[J]. Circulation, 2018, 137(5): e15-28. DOI:10.1161/cir.0000000000000536 |

| [63] |

Herzog JI, Schmahl C. Adverse childhood experiences and the consequences on neurobiological, psychosocial, and somatic conditions across the lifespan[J]. Front Psychiatry, 2018, 9: 420. DOI:10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00420 |

| [64] |

Hein TC, Monk CS. Research Review:Neural response to threat in children, adolescents, and adults after child maltreatment-a quantitative Meta-analysis[J]. J Child Psychol Psychiatry, 2017, 58(3): 222-230. DOI:10.1111/jcpp.12651 |

| [65] |

Bick J, Nelson CA. Early adverse experiences and the developing brain[J]. Neuropsychopharmacology:official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology, 2016, 41(1): 177-196. DOI:10.1038/npp.2015.252 |

| [66] |

Raymond C, Marin MF, Majeur D, et al. Early child adversity and psychopathology in adulthood:HPA axis and cognitive dysregulations as potential mechanisms[J]. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry, 2017, 85: 152-160. DOI:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2017.07.015 |

| [67] |

Obi IE, Mcpherson KC, Pollock JS. Childhood adversity and mechanistic links to hypertension risk in adulthood[J]. Br J Pharmacol, 2019, 176(12): 1932-1950. DOI:10.1111/bph.14576 |

| [68] |

Yang BZ, Zhang HP, Ge WJ, et al. Child abuse and epigenetic mechanisms of disease risk[J]. Am J Prev Med, 2013, 44(2): 101-107. DOI:10.1016/j.amepre.2012.10.012 |

| [69] |

Ridout KK, Levandowski M, Ridout SJ, et al. Early life adversity and telomere length:a Meta-analysis[J]. Mol Psychiatry, 2018, 23(4): 858-871. DOI:10.1038/mp.2017.26 |

| [70] |

Huffhines L, Noser A, Patton SR. The link between adverse childhood experiences and diabetes[J]. Curr Diab Rep, 2016, 16(6): 54. DOI:10.1007/s11892-016-0740-8 |

| [71] |

Ben-Shlomo Y, Cooper R, Kuh D. The last two decades of life course epidemiology, and its relevance for research on ageing[J]. Int J Epidemiol, 2016, 45(4): 973-988. DOI:10.1093/ije/dyw096 |

2020, Vol. 41

2020, Vol. 41