文章信息

- 王晨冉, 孙杨华, 徐韬.

- Wang Chenran, Sun Yanghua, Xu Tao

- 孕妇吸烟与儿童孤独症谱系障碍关系队列研究的Meta分析

- Cohort studies on the association between maternal smoking during pregnancy and autism spectrum disorders of children: a Meta-analysis

- 中华流行病学杂志, 2020, 41(11): 1921-1926

- Chinese Journal of Epidemiology, 2020, 41(11): 1921-1926

- http://dx.doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn112338-20191009-00722

-

文章历史

收稿日期: 2019-10-09

2. 苏州大学医学部公共卫生学院 215000

2. School of Public Health, Medical College of Soochow University, Suzhou 215000, China

孤独症谱系障碍(autism spectrum disorders,ASD)是以社交困难、学习和认知功能障碍、重复刻板行为为主要特点的发育障碍性疾病[1],美国精神病学会将其定义为一类具有高度异质性的疾病谱系[2]。目前各国报道的ASD患病率存在差异:全球ASD的现患率约为1/132(0.76%)[3],美国ASD患病率由1990年的(4~5)/万[4]增至2014年的1/68(1.47%)[5];我国儿童ASD的患病率约为0.39%[6]。健康和疾病的发育起源(developmental origins of health and disease,DOHaD)理论认为,个体在特定的敏感期(如胎儿期)暴露于环境有害因素会对儿童期的健康产生永久性影响[7-8]。研究表明孕妇吸烟会增加早产、低出生体重、儿童期语言发育障碍、注意缺陷多动障碍和攻击性行为的风险[9-12],但目前有关孕妇吸烟对儿童ASD影响的研究存在设计类型不统一、研究结论不一致等问题[13-15]。本研究采用Meta分析方法对近20年的队列研究文献进行分析,定量评价孕妇吸烟与儿童ASD的因果关系。

资料与方法1.文献检索策略:采取MeSH词和自由词结合的形式,以布尔逻辑检索式[(“smoke” OR “smoking” OR “tobacco” OR “cigarette” OR “risk factors”)AND(“pregnancy” OR “prenatal” OR “perinatal” OR “maternal” OR “paternal” OR “parental”)AND(“autism” OR “autism spectrum disorder” OR “ASD” OR “Spectrum Disorders”)AND(“cohort study” OR “longitudinal” OR “follow” OR “follow-up”)]检索PubMed、Embase、Web of Science、Cochrane Library数据库,以“吸烟”“烟草”“孕妇”“产妇”“婴幼儿”“儿童”“孤独症或ASD”“队列研究”为主题词检索中国知网、万方数据知识服务平台中文数据库2000年1月至2019年7月发表的有关孕妇吸烟和儿童ASD关系的队列研究类型文献,同时辅以手工检索和参考文献追溯。

2.纳入和排除标准:

(1)纳入标准:①孕妇吸烟和子代ASD关系的队列研究;②原始研究中有具体的RR值(95%CI)或可转化为RR值(95%CI)的数据;③母亲无精神性疾病、新生儿未患有先天性缺陷且家族内无聚集性精神疾病病史;④儿童年龄为 < 18周岁。

(2)排除标准:①研究类型为生态学研究、横断面研究或病例对照研究(包括巢式病例对照研究和病例队列研究);②未以孕妇吸烟为暴露因素、以ASD患病率调查为研究目的或其他精神性疾病(如抽动秽语综合征、注意缺陷多动障碍)为研究结局;③原始研究中未明确RR值(95%CI)或不能根据提供的参数计算效应值;④以动物为研究对象或在分子水平上开展的研究;⑤重复文献、报告、综述或Meta分析类文献。

3.数据提取:对纳入分析的文献提取以下信息:①基本信息:第一作者、发表年份、研究国家;②队列特点:设计类型、随访时间;③研究人群、暴露和结局:病例数、样本量、儿童年龄、吸烟评估时间、RR值(95%CI)、调整变量。数据提取由第一作者和第二作者分别独立完成,并经双方讨论后达成一致。

4.质量评价:采用纽卡斯尔-渥太华量表(Newcastle-Ottawa Scale,NOS)对纳入的研究进行质量评估。NOS包括队列选择、队列间的可比性、结局3个类别8个条目,总得分为9分[16]。总分7~9为高质量,4~6分为中质量,≤3分为低质量。第一作者和第二作者分别对研究进行独立评价,出现不一致时由第三作者再进行独立评价,共同讨论采纳多数人意见。

5.统计学分析:将RR值(95%CI)作为评价孕妇吸烟和儿童ASD关系的效应测量指标,其中对于已调整变量的研究纳入分析矫正后RR值,对于未调整变量的研究纳入分析未矫正RR值。对于仅提供RR值和队列研究完整事件发生数和未发生数的研究[17],考虑到抽样误差的存在,用Woolf法计算其95%CI:Var lnRR=

运用Stata 15.1软件进行Meta分析。用I2统计量描述各研究间异质性,若I2≥50.00%,采用DerSimonian and Laird随机效应模型合并RR值,反之用Inverse-Variance固定效应模型合并RR值。采用亚组分析和Meta回归探索异质性来源;并通过Meta回归图展示协变量对结果的影响。采用倒漏斗图形法识别发表偏倚,同时结合Begg秩相关法和Egger线性回归法检验漏斗图的不对称性。采用不同效应模型法和影响分析法进行敏感性分析,评估研究结果的稳定性。检验水准为双侧α=0.05。

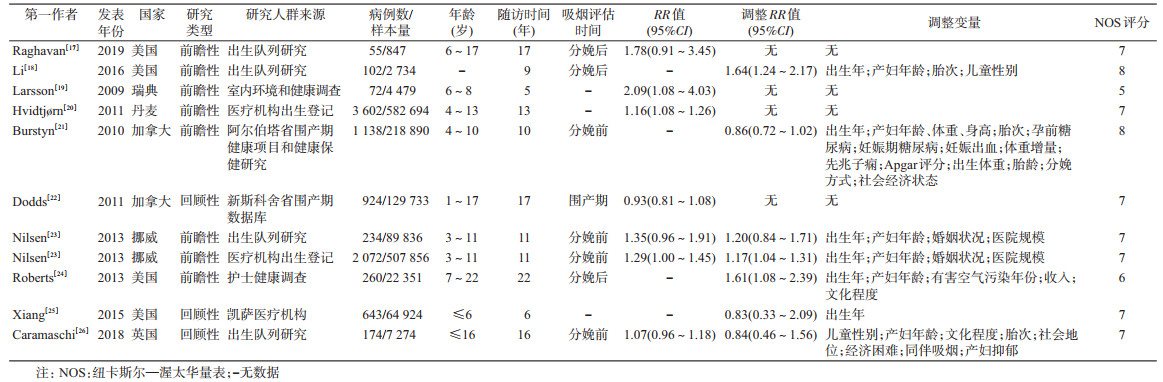

结果1.文献纳入情况:共检索到2 254篇文献,最终10篇文献11项(其中Nilsen于2013年发表的文献同时报告了两项研究结果)研究纳入分析[17-26]。见图 1。

|

| 图 1 文献筛选流程图 |

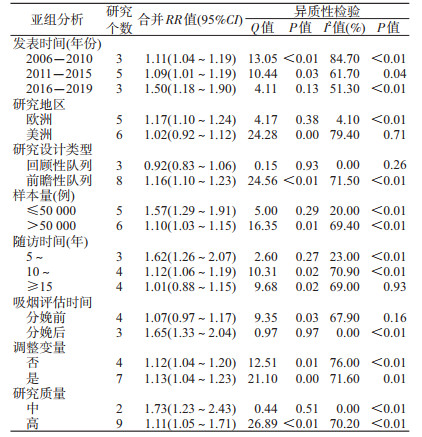

2.文献基本特征和质量评价:11项研究中3项为回顾性队列研究,8项为前瞻性队列研究,累计1 631 618例样本和9 276例ASD病例。文献发表时间为2009-2018年。无符合纳入标准的中文研究。研究人群来自瑞典、丹麦、加拿大、挪威、美国、英国6个国家。7项研究校正了混杂因素。质量评分范围为5~8分,均值为6.9分,其中9项(81.8%)研究为高质量(得分≥7分)。见表 1。

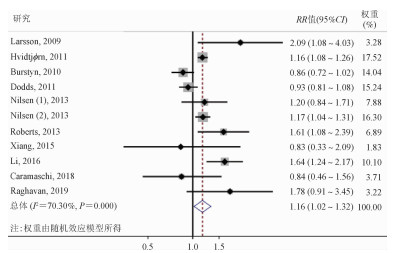

3.合并效应值分析:因研究间存在异质性(I2=70.30%,P < 0.001),用DerSimonian and Laird随机效应模型合并RR值为1.16(95%CI:1.02~1.32),差异有统计学意义(z=2.23,P=0.026),提示孕妇吸烟可增加儿童ASD的发病风险(图 2)。

|

| 图 2 孕妇吸烟与儿童ASD关系的Meta分析森林图 |

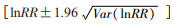

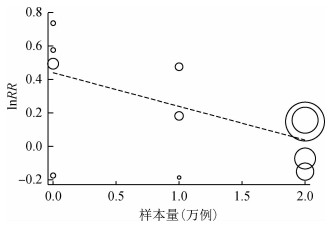

4.亚组分析和Meta回归分析:2016年后发表的文献、欧洲国家、样本量≤50 000例、随访时间为5~9年、分娩后评估、调整变量及中质量研究的合并RR值及同质性较高(表 2)。Meta回归分析结果显示,样本量(t=-2.93,P=0.02)、吸烟评估时间(t=2.85,P=0.04)为可能的异质性来源,其他研究变量与异质性的关系无统计学意义。分别以样本量和RR值为协变量和因变量建立回归模型并绘制Meta回归图,结果表明样本量越大对效应值的影响越大(图 3)。

|

| 注:圆的面积表示单项研究所提供的信息量多少及对效应值的影响大小 图 3 RR对数值与样本量的Meta回归分析 |

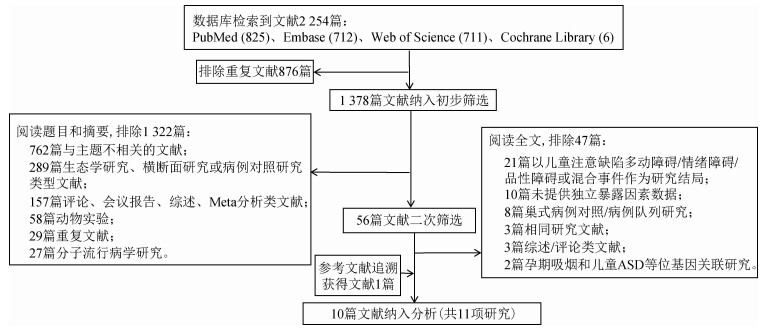

5.发表偏倚检验:Begg秩相关检验所得z=0.16,P=0.88;Egger线性回归法所得t=0.63,P=0.55,差异均无统计学意义。漏斗图(图 4)显示无明显不对称,因此本研究无明显发表偏倚。

|

| 图 4 Meta分析漏斗图 |

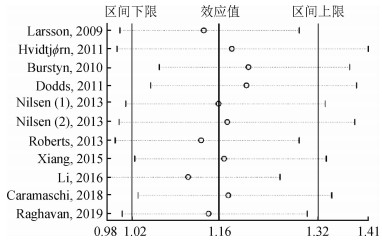

6.敏感性分析:固定效应模型Inverse-Variance法合并RR值为1.12(95%CI:1.06~1.18),DerSimonian and Laird随机效应模型合并RR值为1.16(95%CI:1.02~1.32),则小样本研究对合并效应量的影响不大。影响分析法结果显示,每项研究分别被剔除后对其他研究的合并RR值无明显影响,且各合并RR值的点估计值均在1.16(95%CI:1.06~1.18)内。均提示本研究结果稳定较好(图 5)。

|

| 注:每行表示剔除该项研究后的合并RR值(95%CI) 图 5 影响分析法敏感性分析结果 |

孕妇吸烟对ASD的作用具有生物学合理性。研究表明,烟草中主要的化学物质尼古丁会透过胎盘屏障进入胎儿体内,影响胎儿大脑发育,引起认知功能受损[27-28]。ASD和母亲宫内睾丸激素水平呈正相关,孕妇吸烟会增加睾丸激素水平,进而增加ASD的发生风险[29]。此外,Leppert等[30]发现,神经系统发育的多基因风险评分与孕期吸烟相关,ASD相关基因变异导致的胎儿早期神经系统发育异常也是潜在的致病因素。尽管以上机制提示孕妇吸烟可能是子代ASD的危险因素,但针对两者关联开展的流行病学研究至今未得到一致结论。

2015年发表的两项Meta分析均显示[31-32],在同时纳入病例对照研究和队列研究的情况下,孕妇吸烟对儿童ASD影响的合并效应值无统计学意义(OR=1.02,95%CI:0.93~1.13和OR=1.02,95%CI:0.93~1.12)。吴丹等[33]对病例对照研究进行的Meta分析发现,孕产期主、被动吸烟是ASD的危险因素(OR=2.20,95%CI:1.60~3.03)。本研究与上述研究的不同之处,是仅纳入了队列研究,结果显示孕期吸烟者与不吸烟者相比,其子代发生ASD的风险增加了1.16倍。进一步分析发现,回顾性队列研究的合并效应值无统计学意义,原因可能是回顾性队列研究收集暴露资料时结局已出现,存在诸多研究者无法控制的因素,从而影响研究的效能。与横断面研究和病例对照研究相比,队列研究(特别是前瞻性队列研究)符合先因后果的时间顺序,因此检验孕妇吸烟为儿童ASD病因的能力较强。

本研究发现,分娩后评估吸烟状况、随访时间为5~9年、样本量≤50 000例的研究合并RR值较高、且研究间的异质性较低。在评估时间方面,Meta回归提示吸烟评估时间为可能的异质性来源,亚组分析发现分娩后评估吸烟的研究效应值高于分娩前评估。原因是吸烟状态(即暴露因素)的评定主要依赖于孕妇自我陈述,而在妊娠期接受调查者可能未真实回答孕期吸烟史以致低估暴露水平[31, 34]。另外,本研究结果显示样本量较大、随访时间较长的研究间异质性较高,这正是此类研究实施过程中所面临的挑战。

本研究存在不足。首先,不是所有被纳入的研究均校正了混杂因素,无法避免吸烟量、被动吸烟[35]、ASD亚型[36]等潜在因素的干扰,且不同国家对ASD的诊断率和报告率也存在差异[37]。其次,纳入分析的研究只涉及欧洲和美洲6个国家的研究人群,没有发现符合纳入标准的国内研究。不同国家在环境、种族、人群易感性等方面存在差异,因此结论外推性受限。尽管如此,本研究对国外近20年的队列研究进行分析,减少了横断面研究和病例对照研究存在的偏倚,支持了孕期吸烟会造成子代发生ASD的流行病学假设,可为我国ASD生命早期预防策略的制定提供依据。但现有研究的合并效应值较低、人群代表性较差。未来应开展高质量的大样本、前瞻性队列研究,在矫正潜在混杂因素的基础上深入分析两者的因果关系。

利益冲突 所有作者均声明不存在利益冲突

| [1] |

Lai MC, Lombardo MV, Baron-Cohen S. Autism[J]. Lancet, 2014, 383(9920): 896-910. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61539-1 |

| [2] |

Drislane LE, Sellbom M, Brislin SJ, et al. Improving characterization of psychopathy within the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), alternative model for personality disorders:Creation and validation of Personality Inventory for DSM-5 Triarchic scales[J]. Personal Disord, 2019, 10(6): 511-523. DOI:10.1037/per0000345 |

| [3] |

Baxter AJ, Brugha TS, Erskine HE, et al. The epidemiology and global burden of autism spectrum disorders[J]. Psychol Med, 2015, 45(3): 601-613. DOI:10.1017/s003329171400172x |

| [4] |

Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network Surveillance Year 2008 Principal Investigators, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorders-Autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 14 Sites, United States, 2008[J]. MMWR Surveill Summ, 2012, 61(3): 1-19. |

| [5] |

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC estimates 1 in 68 children has been identified with autism spectrum disorder[EB/OL]. (2014-03-27). https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2014/p0327-autism-spectrum-disorder.html.

|

| [6] |

Wang F, Lu L, Wang SB, et al. The prevalence of autism spectrum disorders in China:a comprehensive Meta-analysis[J]. Int J Biol Sci, 2018, 14(7): 717-725. DOI:10.7150/ijbs.24063 |

| [7] |

Angelidou A, Asadi S, Alysandratos KD, et al. Perinatal stress, brain inflammation and risk of autism-Review and proposal[J]. BMC Pediatr, 2012, 12: 89. DOI:10.1186/1471-2431-12-89 |

| [8] |

Haugen AC, Schug TT, Collman G, et al. Evolution of DOHaD:the impact of environmental health sciences[J]. J Dev Orig Health Dis, 2015, 6(2): 55-64. DOI:10.1017/s2040174414000580 |

| [9] |

Wisborg K, Henriksen TB, Hedegaard M, et al. Smoking during pregnancy and preterm birth[J]. Br J Obstet Gynaecol, 2010, 103(8): 800-805. DOI:10.1111/j.1471-0528.1996.tb09877.x |

| [10] |

Tominey E. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and early child outcomes[M]. London: Centre for Economic Performance, London School of Economics and Political Science, 2007.

|

| [11] |

Skoglund C, Chen Q, D'Onofrio BM, et al. Familial confounding of the association between maternal smoking during pregnancy and ADHD in offspring[J]. J Child Psychol Psychiatry, 2013, 55(1): 61-68. DOI:10.1111/jcpp.12124 |

| [12] |

Indredavik MS, Brubakk AM, Romundstad P, et al. Prenatal smoking exposure and psychiatric symptoms in adolescence[J]. Acta Paediatr, 2007, 96(3): 377-382. DOI:10.1111/j.1651-2227.2006.00148.x |

| [13] |

Hultman CM, Sparén P, Cnattingius S. Perinatal risk factors for infantile autism[J]. Epidemiology, 2002, 13(4): 417-423. DOI:10.1097/00001648-200207000-00009 |

| [14] |

Maimburg RD, Væth M. Perinatal risk factors and infantile autism[J]. Acta Psychiatr Scand, 2010, 114(4): 257-264. DOI:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00805.x |

| [15] |

Tran PL, Lehti V, Lampi KM, et al. Smoking during pregnancy and risk of autism spectrum disorder in a Finnish national birth cohort[J]. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol, 2013, 27(3): 266-274. DOI:10.1111/ppe.12043 |

| [16] |

Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in Meta-analyses[J]. Eur J Epidemiol, 2010, 25(9): 603-605. DOI:10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z |

| [17] |

Raghavan R, Fallin MD, Hong XM, et al. Cord and early childhood plasma adiponectin levels and autism risk:A prospective birth cohort study[J]. J Autism Dev Disord, 2019, 49(1): 173-184. DOI:10.1007/s10803-018-3688-5 |

| [18] |

Li MY, Fallin MD, Riley A, et al. The association of maternal obesity and diabetes with autism and other developmental disabilities[J]. Pediatrics, 2016, 137(2): e20152206. DOI:10.1542/peds.2015-2206 |

| [19] |

Larsson M, Weiss B, Janson S, et al. Associations between indoor environmental factors and parental-reported autistic spectrum disorders in children 6-8 years of age[J]. Neurotoxicology, 2009, 30(5): 822-831. DOI:10.1016/j.neuro.2009.01.011 |

| [20] |

Hvidtjørn D, Grove J, Schendel D, et al. Risk of autism spectrum disorders in children born after assisted conception:a population-based follow-up study[J]. J Epidemiol Community Health, 2011, 65(6): 497-502. DOI:10.1136/jech.2009.093823 |

| [21] |

Burstyn I, Sithole F, Zwaigenbaum L. Autism spectrum disorders, maternal characteristics and obstetric complications among singletons born in Alberta, Canada[J]. Chronic Dis Can, 2010, 30(4): 125-134. DOI:10.24095/hpcdp.30.4.04 |

| [22] |

Dodds L, Fell DB, Shea S, et al. The role of prenatal, obstetric and neonatal factors in the development of autism[J]. J Autism Dev Disord, 2011, 41(7): 891-902. DOI:10.1007/s10803-010-1114-8 |

| [23] |

Nilsen RM, Surén P, Gunnes N, et al. Analysis of self-selection bias in a population-based cohort study of autism spectrum disorders[J]. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol, 2013, 27(6): 553-563. DOI:10.1111/ppe.12077 |

| [24] |

Roberts AL, Lyall K, Hart JE, et al. Perinatal air pollutant exposures and autism spectrum disorder in the children of nurses' health study Ⅱ participants[J]. Environ Health Perspect, 2013, 121(8): 978-984. DOI:10.1289/ehp.1206187 |

| [25] |

Xiang AH, Wang XH, Martinez MP, et al. Association of maternal diabetes with autism in offspring[J]. JAMA, 2015, 313(14): 1425. DOI:10.1001/jama.2015.2707 |

| [26] |

Caramaschi D, Taylor AE, Richmond RC, et al. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and autism:using causal inference methods in a birth cohort study[J]. Transl Psychiatry, 2018, 8(1): 262. DOI:10.1038/s41398-018-0313-5 |

| [27] |

Tiesler CMT, Heinrich J. Prenatal nicotine exposure and child behavioural problems[J]. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 2014, 23(10): 913-929. DOI:10.1007/s00787-014-0615-y |

| [28] |

Herrmann M, King K, Weitzman M. Prenatal tobacco smoke and postnatal secondhand smoke exposure and child neurodevelopment[J]. Curr Opin Pediatr, 2008, 20(2): 184-190. DOI:10.1097/mop.0b013e3282f56165 |

| [29] |

James WH. Potential explanation of the reported association between maternal smoking and autism[J]. Environ Health Perspect, 2013, 121(2): a42. DOI:10.1289/ehp.1206268 |

| [30] |

Leppert B, Havdahl A, Riglin L, et al. Association of maternal neurodevelopmental risk alleles with early-life exposures[J]. JAMA Psychiatry, 2019, 76(8): 834-842. DOI:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.0774 |

| [31] |

Tang SM, Wang Y, Gong X, et al. A Meta-analysis of maternal smoking during pregnancy and autism spectrum disorder risk in offspring[J]. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2015, 12(9): 10418-10431. DOI:10.3390/ijerph120910418 |

| [32] |

Rosen BN, Lee BK, Lee NL, et al. Maternal smoking and autism spectrum disorder:A Meta-analysis[J]. J Autism Dev Disord, 2015, 45(6): 1689-1698. DOI:10.1007/s10803-014-2327-z |

| [33] |

吴丹, 王嘉淇, 周丽, 等. 孕产期环境因素与儿童孤独症关系的Meta分析[J]. 中国妇幼保健, 2016, 31(18): 3870-3872. Wu D, Wang JQ, Zhou L, et al. Relationship between perinatal environmental factors and childhood autism:A Meta-analysis[J]. Maternal Child Health Care China, 2016, 31(18): 3870-3872. DOI:10.7620/zgfybj.j.issn.1001-4411.2016.18.79 |

| [34] |

Burstyn I, Kapur N, Shalapay C, et al. Evaluation of the accuracy of self-reported smoking in pregnancy when the biomarker level in an active smoker is uncertain[J]. Nicotine Tob Res, 2009, 11(6): 670-678. DOI:10.1093/ntr/ntp048 |

| [35] |

Duan GQ, Yao ML, Ma YT, et al. Perinatal and background risk factors for childhood autism in central China[J]. Psychiatry Res, 2014, 220(1/2): 410-417. DOI:10.1016/j.psychres.2014.05.057 |

| [36] |

Visser JC, Rommelse N, Vink L, et al. Narrowly versus broadly defined autism spectrum disorders:differences in pre- and perinatal risk factors[J]. J Autism Dev Disord, 2013, 43(7): 1505-1516. DOI:10.1007/s10803-012-1678-6 |

| [37] |

Durkin MS, Maenner MJ, Meaney FJ, et al. Socioeconomic inequality in the prevalence of autism spectrum disorder:Evidence from a U.S. cross-sectional study[J]. PLoS One, 2010, 5(7): e11551. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0011551 |

2020, Vol. 41

2020, Vol. 41