文章信息

- 张家晖, 岳晓丽, 李婧, 龚向东.

- Zhang Jiahui, Yue Xiaoli, Li Jing, Gong Xiangdong

- 全国性病监测点实验室检测能力调查

- Investigation of detection capacities of laboratories in sexually transmitted disease surveillance areas in China

- 中华流行病学杂志, 2020, 41(9): 1509-1513

- Chinese Journal of Epidemiology, 2020, 41(9): 1509-1513

- http://dx.doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn112338-20191115-00812

-

文章历史

收稿日期: 2019-11-15

实验室检测是监测的重要基础, 性病监测点实验室的检测能力直接影响性病检测和诊断的质量, 从而影响病例报告的准确性, 加强实验室能力建设显得尤其重要.中国CDC性病控制中心(性病中心)曾于2008年开展了全国105个以县区为单位的性病监测点实验室检测状况的基线调查, 发现了存在的不足, 提出了改进建议[1].为了进一步了解性病监测点医疗机构性病实验室检测现状, 加强性病实验室的能力建设, 促进病例报告工作, 性病中心于2017年8月组织开展了全国性病监测点医疗机构性病实验室检测能力调查.

对象与方法1.调查对象:全国31个省(直辖市、自治区)105个国家级性病监测点内开展性病诊疗和病例报告的各级各类医疗机构.根据监测点医疗机构的平均数量, 各监测点的调查数量标准: ①医疗机构数量≤8家, 则全部调查; ②医疗机构数量≥9家, 则调查其中8家不同级别、不同类型、报告性病病例数较多的医疗机构.

2.调查内容与方法:采用横断面调查设计. 2017年8-10月开展现场调查, 11月上报数据库.由性病中心组织专家制定调查方案.调查开始前, 统一培训调查人员, 由省级CDC(或皮肤性病防治机构)组织本省范围内国家级性病监测点现场调查.使用统一设计的"监测点医疗机构性病实验室检测方法调查表"收集信息, 包括医疗机构的单位级别、类型和性质、开展的性病实验室检测项目等.调查的检测项目: ①梅毒血清学试验, 包括梅毒螺旋体血清学试验(特异性试验)、非梅毒螺旋体血清学试验(非特异性试验)、暗视野梅毒螺旋体镜检; ②淋球菌涂片革兰染色镜检、淋球菌培养和核酸检测; ③生殖道沙眼衣原体(CT)抗原快速检测和核酸检测; ④单纯疱疹病毒2型(HSV-2)抗体检测、抗原检测和核酸检测; ⑤人乳头瘤病毒(HPV)低危型(6、11型等)和高危型(16、18型等)核酸检测等.

3.统计学分析:采用EpiData 3.1软件录入数据、R 3.5.3软件分析数据.使用频数和比例描述各调查变量的特征, 应用χ2检验对各分类资料构成或比例的差异进行统计检验, 以P < 0.05为差异有统计学意义.

结果1.实验室检测项目总体情况:共对104个监测点752家医疗机构开展调查.有1个监测点(西藏自治区拉萨市性病监测点)未开展调查, 数据缺失.

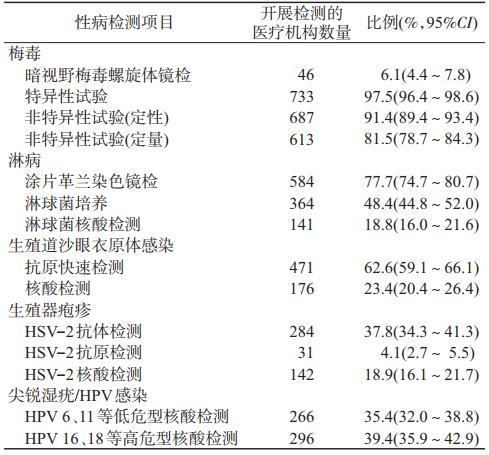

752家医疗机构开展的性病检测项目结果见表 1.开展梅毒血清学试验的比例较高, 开展其他性病检测方法的比例均较低.在梅毒特异性试验方面, 有406家开展了梅毒螺旋体颗粒凝集试验, 343家开展了酶联免疫吸附试验, 306家开展了快速免疫层析法, 206家开展了化学发光法, 分别占54.0%、45.6%、40.7%和27.4%;在非特异性试验方面, 有479家开展了甲苯胺红不加热血清试验, 298家开展了快速血浆反应素环状卡片试验, 分别占63.7%和39.6%.

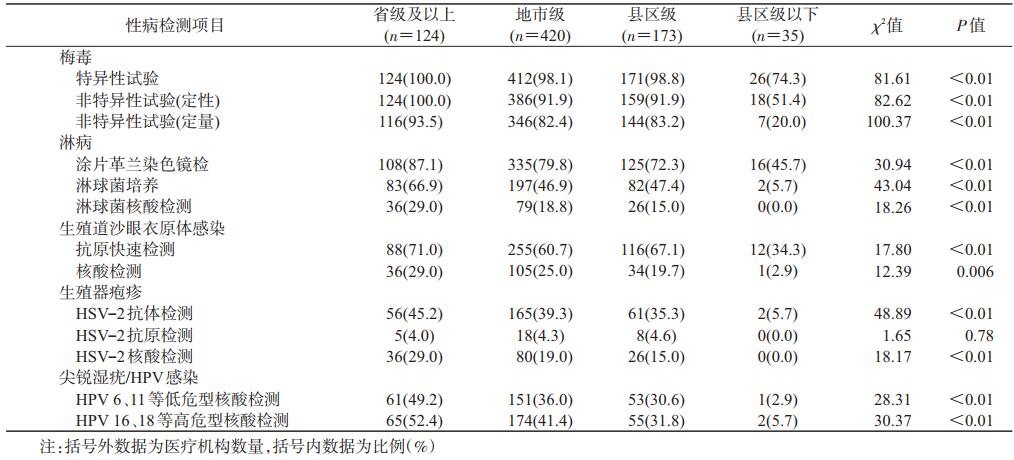

2.开展性病检测项目:按所属审批机关将医疗机构分为省级及以上、地市级、县区级和县区级以下4级, 分别占调查医疗机构的16.4%(124/752)、55.9%(420/752)、23.0%(173/752)和4.7%(35/752).各级医疗机构开展的性病检测项目(HSV-2抗原检测除外)的比例差异有统计学意义, 省级及以上最高, 县区级以下最低.省级及以上高于地市级与县区级, 但地市级与县区级基本相当.见表 2.

3.不同类型医疗机构开展性病检测项目比较:在接受调查的752家医疗机构中, 综合医院、皮肤性病专科医院、妇幼保健机构和其他类型机构分别占69.9%(526/752)、4.4%(33/752)、16.1%(121/752)和9.6%(72/752).总体而言, 皮肤性病专科医院开展的性病检测项目高于其他3种类型医疗机构, 尤其是淋球菌培养项目皮肤性病专科医院(97%)远高于其他类型医疗机构(< 60%); 对于HPV核酸检测, 妇幼保健机构略高于其他3种类型医疗机构.见表 3.

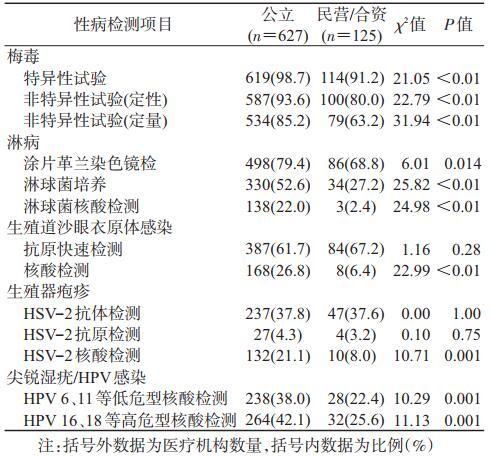

4.公立、民营及合资医疗机构开展性病检测项目比较:按登记注册类型将医疗机构分为公立、民营/合资医疗机构, 分别占调查医疗机构的83.4%(627/752)和16.6%(125/752).多数性病检测项目(梅毒、淋病、尖锐湿疣/HPV感染、CT核酸检测、HSV-2核酸检测), 公立医疗机构开展的比例高于民营/合资医疗机构.见表 4.

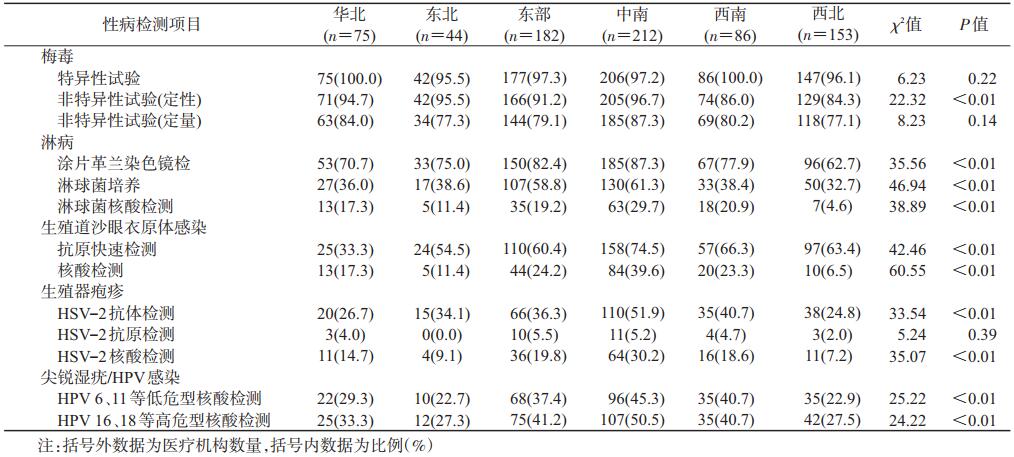

5.不同地区医疗机构开展性病检测项目比较:将监测点所分布的省份划分为6大地理区域(华北、东北、华东、中南、西南和西北)进行统计分析, 各区域监测点调查的医疗机构数量分别占10.0%(75/752)、5.9%(44/752)、24.2%(182/752)、28.2%(212/752)、11.4%(86/752)和20.3%(153/752).西北地区监测点医疗机构开展的性病检测项目比例略低于其他5个区域.对于淋球菌培养开展的比例, 中南和东部地区(>55%)显著高于其他4个区域(< 40%).见表 5.

我国性病监测点监测工作始于1987年, 由原卫生部选择了16个城市作为性病监测试点, 1993年在世界银行支持下, 监测点扩大到26个[2], 2008年进一步增加到105个.性病监测点是以县区为单位, 通过分层抽样方法选取, 在监测点内开展加强了性病病例报告和人群感染率专题调查[2].监测点内医疗机构开展性病实验室的检测能力对保障监测数据质量尤为重要, 有必要持续了解和加强实验室检测工作.因此, 性病中心在2008年基线调查的基础上开展此次调查.

本调查结果显示, 性病监测点医疗机构开展梅毒血清特异性试验和非特异性试验的比例均>90%, 而开展淋球菌培养与核酸检测、CT核酸检测的比例很低(< 50%), 可能与梅毒血清学检测试剂普及、价廉、操作简便快速、所需仪器设备和实验室条件要求简单有关.

与2008年基线调查结果相比, 2类梅毒血清学检测方法明显提高(2008年分别为39.98%和74.52%)[1], 淋球菌培养与核酸检测、CT核酸检测比例也得到提高, 表明加强监测点实验室建设取得了一定效果.但开展淋球菌培养与核酸检测、CT核酸检测的比例提高幅度不够显著(2008年分别为35.59%、9.35%、10.59%)[1].

淋球菌培养和核酸检测为WHO和美国CDC推荐的检测方法, 在发达国家已普遍应用[3-6].淋球菌培养和核酸检测对女性淋病诊断十分重要, 女性淋病大多数无症状, 淋球菌涂片革兰染色镜检对于男性淋病诊断的敏感性达到99%, 但对女性诊断的灵敏度低于50%[3-4]; 此外, 涂片革兰染色镜检对于咽部和直肠淋球菌感染检测的灵敏度也很低, 因此不推荐使用涂片革兰染色镜检诊断女性淋病以及咽部与直肠感染, 而是使用淋球菌培养或核酸检测方法[6].淋球菌培养和核酸检测在我国开展普遍不足可能是导致淋病报告病例中男性远多于女性的原因之一[7-8], 这与欧美国家淋病报告情况不同[6, 9-10]; 也表明我国目前淋病病例报告中可能存在较为严重的漏诊和低报告现象.

同样, CT抗原快速检测对男、女性CT感染检测的灵敏度均较低(< 85%), WHO推荐使用核酸检测方法对CT感染进行检测[3], CT核酸检测在欧美发达国家也得到普遍应用.本次调查监测点医疗机构开展CT核酸检测的比例仅为23.4%(176/752), 这也可能是我国性病监测点CT感染报告发病率明显低于发达国家的原因之一[11], 表明我国目前CT感染病例报告中也可能存在较为严重的漏诊和低报告现象.

本次调查结果显示, 不同级别、不同类型、不同经营性质的医疗机构开展性病检测项目的比例差异明显.总体上, 省级及以上医疗机构开展性病检测项目较全面, 地市级和县区级次之, 县区级以下最低; 皮肤性病专科医疗机构高于综合医疗机构和妇幼保健机构, 其他医疗机构开展比例最低; 民营/合资医疗机构低于公立医疗机构.此外, 不同地理区域监测点医疗机构开展性病检测项目的比例不同, 表明存在地区发展不平衡现象, 经济较为发达的华东和中南地区开展性病检测项目的比例较高, 经济欠发达的西北地区最低.

今后需要进一步加大监测点医疗机构性病实验室检测能力建设的力度, 尤其要不断提高淋球菌培养与核酸检测、CT核酸检测能力, 促进使用灵敏度和特异度均高的核酸检测方法.梅毒血清学试验检测项目仍有提升空间, 尤其是非特异性试验, 应做到基本普及, 并不断促进医疗机构开展定量检测.国家需要制定医疗机构性病实验室能力建设规划, 国家和地方卫生健康行政部门有重点、分步骤加大基层、西部和民营医疗机构实验室建设投入, 为切实提高性病诊断和病例报告准确性提供支撑.

利益冲突 所有作者均声明不存在利益冲突

志谢 感谢全国各省级CDC和皮肤性病防治机构有关工作人员在数据收集中所做的贡献

| [1] |

龚向东, 岳晓丽, 腾菲, 等. 我国性病监测点实验室检测状况基线调查分析[J]. 中国艾滋病性病, 2010, 16(2): 99-104. Gong XD, Yue XL, Teng F, et al. Baseline survey on laboratory testing of sexually transmitted diseases at national STD surveillance sites[J]. Chin J AIDS STD, 2010, 16(2): 99-104. DOI:10.13419/j.cnki.aids.2010.02.029 |

| [2] |

邵长庚, 梁国钧, 龚向东, 等. 中国性病监测的回顾和展望[J]. 中国性病艾滋病防治, 2002, 8(4): 247-250. Shao CG, Liang GJ, Gong XD, et al. The review and prospect of STD surveillance in China[J]. Chin J STD AIDS Prev Cont, 2002, 8(4): 247-250. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1672-5662.2002.04.024 |

| [3] |

World Health Organization. Strategies and laboratory methods for strengthening surveillance of sexually transmitted infection 2012[Z/OL]. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2012. http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/rtis/9789241504478/en/index.html.

|

| [4] |

Papp JR, Schachter J, Gaydos CA, et al. Recommendations for the laboratory-based detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae-2014[J]. MMWR Recomm Rep, 2014, 63: 1-19. |

| [5] |

Public Health Agency of Canada. Canadian guidelines on sexually transmitted infections. gonococcal infections chapter/[by] Barbara Romanowski, Joan Robinson, Tom Wong[Z/OL]. 2013.(2013-04-03)[2019-05-13]. http://publications.gc.ca/site/eng/469312/publication.html.

|

| [6] |

Public Health England. Guidance for the detection of gonorrhoea in England[EB/OL]. 2014.(2014-08-13)[2019-05-13]. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/405293/170215_Gonorrhoea_testing_guidance_REVISED_2_.pdf.

|

| [7] |

龚向东, 岳晓丽, 蒋宁, 等. 2000-2014年中国淋病流行特征与趋势分析[J]. 中华皮肤科杂志, 2015, 48(5): 301-306. Gong XD, Yue XL, Jiang N, et al. Epidemiological characteristics and trends of gonorrhea in China from 2000 to 2014[J]. Chin J Dermatol, 2015, 48(5): 301-306. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0412-4030.2015.05.002 |

| [8] |

Yue XL, Gong XD, Li J, et al. Gonorrhea in China, 2018[J]. Int J Dermatol Venereol, 2019, 2(2): 65-69. DOI:10.1097/JD9.0000000000000008 |

| [9] |

Choudhri Y, Miller J, Sandhu J, et al. Gonorrhea in Canada, 2010-2015[J]. Can Commun Dis Rep, 2018, 44(2): 37-42. DOI:10.14745/ccdr.v44i02a01 |

| [10] |

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2017[EB/OL]. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2018.(2018-07-24)[2019-06-07]. https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats17/Gonorrhea.htm.

|

| [11] |

岳晓丽, 龚向东, 滕菲, 等. 2008-2015年中国性病监测点生殖道沙眼衣原体感染流行特征分析[J]. 中华皮肤科杂志, 2016, 49(5): 308-313. Yue XL, Gong XD, Teng F, et al. Epidemiologic features of genital Chlamydia trachomatis infection in national sexually transmitted disease surveillance sites in China from 2008 to 2015[J]. Chin J Dermatol, 2016, 49(5): 308-313. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0412-4030.2016.05.002 |

2020, Vol. 41

2020, Vol. 41