文章信息

- 王欢, 张高辉, 羊柳, 赵敏, 席波.

- Wang Huan, Zhang Gaohui, Yang Liu, Zhao Min, Xi Bo

- 血压测量次数对藏族青少年血压偏高检出率的影响分析

- Effect of blood pressure measurement on detection of elevated blood pressure in Tibetan adolescents

- 中华流行病学杂志, 2020, 41(9): 1440-1444

- Chinese Journal of Epidemiology, 2020, 41(9): 1440-1444

- http://dx.doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn112338-20200308-00277

-

文章历史

收稿日期: 2020-03-08

2. 山东省疾病预防控制中心慢病所, 济南 250014;

3. 山东大学齐鲁医学院公共卫生学院毒理与营养学系, 济南 250012

2. Department of Chronic Non-communicable Disease Control, Shandong Provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Ji'nan 250014, China;

3. Department of Toxicology and Nutrition, School of Public Health, Cheeloo College of Medicine, Shandong University, Ji'nan 250012, China

高血压是导致全球疾病负担的主要原因之一[1],随着超重/肥胖和不健康生活方式在儿童青少年中的流行,高血压呈现低龄化趋势[2]。中国居民健康与营养调查显示,2015年我国9省7~17岁儿童青少年血压偏高检出率为12.8%~20.5%(依据参考标准不同)[2]。研究表明,血压水平从儿童期到成年期具有长期“轨迹现象”[3],且儿童期血压偏高会增加成年期心血管病和早死风险[4]。同时,儿童期血压偏高还会导致近期各种靶器官损害(如颈动脉内中膜增厚、左心室肥厚和微量白蛋白尿等)[5]。各国儿童高血压指南均建议,儿童青少年高血压的诊断应基于至少3次非同日的血压测量进行[6-7]。主要原因是,儿童青少年个体血压的变异性较大、存在白大衣现象和向均数回归等因素,导致其血压水平具有不稳定性[8],从而影响儿童青少年高血压诊断的准确性。美国高血压指南推荐如果首次血压偏高(即血压值高于P90分位数),应再测量2次,取其平均值[7]。欧洲地区和中国儿童高血压指南,都推荐测量3次血压并取后2次的均值作为研究对象的血压水平[6, 9]。2019年,一项基于瑞士5 207名儿童的横断面研究表明,对研究对象测量2次血压,并取第2次血压值用于识别儿童血压偏高,即可达到预期效果[10]。目前,国内外关于探讨血压测量次数对儿童青少年血压水平以及血压偏高检出率的影响较少。本研究旨在比较不同血压测量次数对藏族青少年的血压水平以及血压偏高检出率的影响,为对青少年进行规范测量血压、准确识别血压偏高提供科学依据。

对象与方法1.研究对象:采用方便分层整群抽样的方法,于2018年8-9月在西藏自治区日喀则地区选取3所初中学校(分别位于桑珠孜区、亚东区和岗巴区)和3所高中学校(桑珠孜区)作为样点。本研究共纳入2 822名12~17岁藏族青少年,其中男生1 275人(45.2%)。本研究通过山东大学公共卫生学院伦理委员会审查(批准文号:LL20200602),所有研究对象及其监护人均签署知情同意书。

2.研究方法:采用校正的身高体重测量仪测量身高和体重。测量时研究对象脱鞋帽,穿轻薄衣服,立正姿势平视前方。身高和体重分别精确到0.1 cm和0.1 kg。均各测量2次,取其平均值用于分析。计算BMI=体重(kg)/身高(m)2。采用校正的欧姆龙电子血压计(Omron HBP-1300)测量血压,该血压计经人群验证适合于临床应用和流行病学研究[11]。研究对象测量前1 h内禁饮酒、茶等饮料,不服用影响血压的药物,安静休息>10 min,测量时不穿紧身衣物。连续测量3次,每次间隔>10 s,分别记录3次测量的SBP和DBP。要求3次连续测量血压的两两之间不超过4 mmHg(1 mmHg=0.133 kPa);如果超过,则进行多次测量,直到符合为止。

3.诊断标准:根据2018年原国家卫生和计划生育委员会(卫计委)颁布的我国卫生行业标准——WS/T 610-2018《7岁~18岁儿童青少年血压偏高筛查界值》[12],血压偏高定义为基于单个时点测量的SBP和/或DBP≥性别、年龄和身高别的P95界值。低体重定义采用原卫计委颁布的我国卫生行业标准——WS/T 456-2014《学龄儿童青少年营养不良筛查》[13],超重/肥胖定义采用原卫计委颁布的我国卫生行业标准——WS/T 586-2018《学龄儿童青少年超重与肥胖筛查》[14]。

4.质量控制:所有调查人员均经过培训并考核合格,所有仪器使用前均进行测试和校正。调查人员使用统一的仪器设备、按照统一的方案进行测量,及时进行现场数据核查。采用EpiData 3.0软件建立数据库,所有数据进行双人双录入,并且进行逻辑检查,发现不一致之处,及时查阅原问卷并进行纠正。

5.统计学分析:采用SAS 9.4软件进行数据分析。连续性资料以(x ±s)表示,采用t检验进行两组间差异比较,采用方差分析进行多组间差异比较;分类资料以频数(百分比,%)表示,采用χ2检验进行组间差异比较。采用线性回归模型分析血压水平随血压测量次数增加的变化趋势,采用Cochran- Armitage趋势χ2检验分析血压偏高检出率随血压测量次数增加的变化趋势。采用双侧检验,检验水准α=0.05。方差分析和χ2检验中两两组间差异比较涉及多重比较,采用双侧检验,检验水准α=0.05/2=0.025。

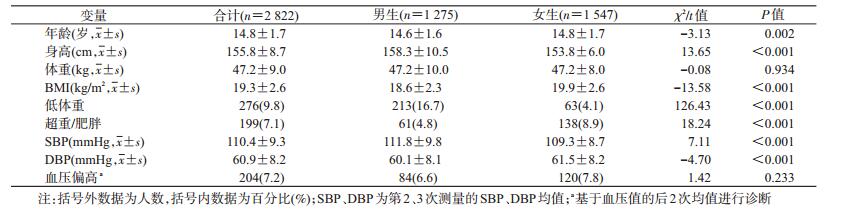

结果1.基本特征:共纳入2 822名12~17岁藏族青少年,男生1 275人(45.2%)。男生的身高、低体重率和SBP均高于女生(均P<0.001),女生的年龄、BMI、超重/肥胖率和DBP均高于男生(均P<0.05)。男女生的体重和血压偏高检出率差异无统计学意义(均P>0.05)。见表 1。

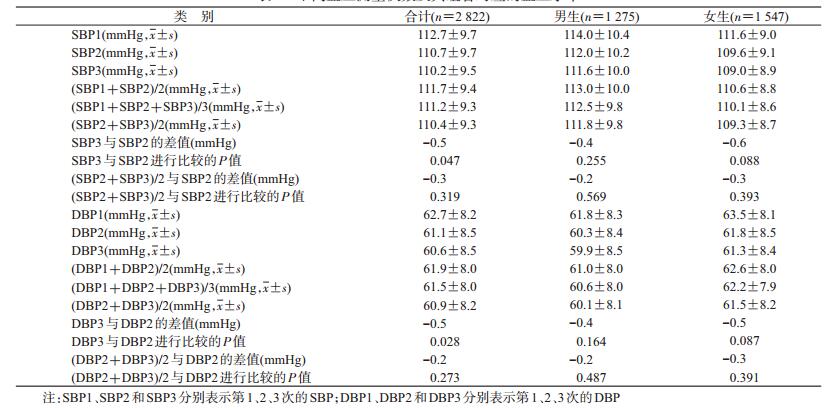

2.不同血压测量次数及其组合血压水平比较:青少年的第1、2、3次SBP依次为(112.7±9.7)、(110.7±9.7)、(110.2±9.5)mmHg,DBP依次为(62.7±8.2)、(61.1±8.5)、(60.6±8.5)mmHg,均呈下降趋势(趋势检验P<0.001)。第2次血压值与第2、3次的血压均值差异均无统计学意义(P>0.025)。按性别进行分层分析,趋势检验与合计相似。另外,第2次血压与第2、3次的血压均值的差值均≤0.3 mmHg,提示两者的绝对血压水平差别很小。见表 2。

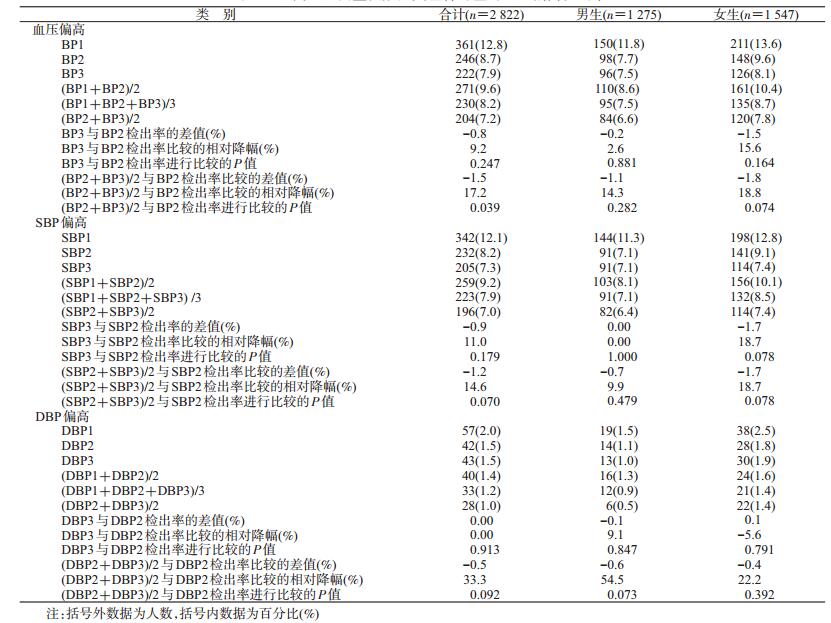

3.不同血压测量次数及其组合血压偏高检出率比较:基于第1、2、3次血压值诊断的血压偏高检出率依次为12.8%、8.7%、7.9%,呈下降趋势(趋势检验P<0.001)。SBP偏高检出率趋势相同(趋势检验P<0.001),但DBP偏高检出率的下降趋势无统计学意义(趋势检验P=0.147)。基于第2次血压值与基于第2、3次血压均值诊断的血压偏高检出率、SBP偏高检出率和DBP偏高检出率,差异均无统计学意义(均P>0.025)。按性别进行分层分析,趋势与合计相似。基于第2次血压值与基于第2、3次血压均值诊断的血压偏高检出率、SBP偏高检出率和DBP偏高检出率的绝对差值均≤1.8%。另外,DBP偏高检出率的下降相对幅度较大。但是,由于青少年的血压偏高主要以SBP偏高为主,因此这对整体结果的影响很小。见表 3。

本研究结果显示,在连续3次的血压测量中,青少年的SBP、DBP和血压偏高检出率均呈下降趋势。值得注意的是,基于第2次血压值与基于第2、3次血压均值诊断的血压偏高检出率趋于一致。这提示,仅基于第2次的血压值,可能足以高效地筛查出青少年血压偏高的高危人群。

血压测量次数较少会高估血压水平,导致假阳性率的增高[8, 15-16]。但是,测量次数较多,给测量者增加工作负担,也给被测者带来不适。2011-2013年澳大利亚健康调查显示,儿童青少年血压具有较大的变异性,并强调明确血压测量次数的重要性[17]。一项基于2010年北京市儿童青少年血压调查数据的研究指出,连续测量的3次血压中,第2、3次测量值趋于接近,作者建议后2次测量的均值代表个体血压水平[18]。但是,作者也提到,为简化程序可测量2次,以第2次测量值作为血压值[18]。近期一项基于瑞士5 207名儿童的横断面研究表明,连续测量的3次血压中,基于第2次血压值就能达到识别儿童血压偏高的目的[10]。本研究结果也支持以第2次测量值作为个体血压值。

目前,关于藏族青少年血压偏高检出率的研究极少。我们通过万方数据知识服务平台、中国知网和PubMed数据库进行了仔细的文献检索,但仅能检索到1篇中文会议摘要[19]和1篇中文论著[20]是关注藏族青少年或青年的血压偏高检出率。因中文会议摘要没有具体的方法学描述(尤其是关于电子血压计的型号未知、该电子血压计是否经过临床验证未知、血压的测量次数未知等),因此结果的可靠性无法考证,故本研究不进行评论。另1篇发表于2014年的中文论著纳入845名15~25岁的青少年和青年人群,由专业的医务人员采用水银血压计测量,共测量3次并取其平均值,本研究采用≥140/90 mmHg诊断高血压。结果表明,在该青少年和青年人群中,未发现有高血压患者。这似乎与我们报告的12~17岁藏族青少年的血压偏高较低(7.2%)一致。在公开发表的文献中,关注中老年藏族人群高血压检出率的研究居多,均表明高血压患病率在23%~56%波动,且随着海拔增高而增高[21]。这可能说明藏族成年人的高血压问题,是随着年龄增长(到中老年期)和遗传环境交互作用的累积效应和长期暴露而最终出现。今后需要有更多的研究关注这一科学问题。

本研究样本量相对较大,质控严格,结果可信度高。但本研究存在两点不足。第一,本研究基于12~17岁藏族青少年,结论外推需谨慎。第二,本研究基于偶测血压值(基于一个时点的3次血压值),不能准确诊断青少年高血压(需要至少非同日三时点随访测量)。

综上所述,随着血压测量次数的增加,藏族青少年血压水平和血压偏高检出率逐渐下降。与基于第2、3次血压均值用于高血压诊断这一“金标准”相比,基于第2次血压值足以用于高效筛查青少年高血压。

利益冲突 所有作者均声明不存在利益冲突

| [1] |

GBD 2017 Risk Factor Collaborators. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 84 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017:a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017[J]. Lancet, 2018, 392(10159): 1923-1994. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32225-6 |

| [2] |

马淑婧, 羊柳, 赵敏, 等. 1991-2015年中国儿童青少年血压水平及高血压检出率的变化趋势[J]. 中华流行病学杂志, 2020, 41(2): 178-183. Ma SJ, Yang L, Zhao M, et al. Changing trends in the levels of blood pressure and prevalence of hypertension among Chinese children and adolescents from 1991 to 2015[J]. Chin J Epidemiol, 2020, 41(2): 178-183. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2020.02.008 |

| [3] |

Chen XL, Wang YF. Tracking of blood pressure from childhood to adulthood:a systematic review and Meta-regression analysis[J]. Circulation, 2008, 117(25): 3171-3180. DOI:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.730366 |

| [4] |

Yang LL, Magnussen CG, Yang L, et al. Elevated blood pressure in childhood or adolescence and cardiovascular outcomes in adulthood:a systematic review[J]. Hypertension, 2020, 75(4): 948-955. DOI:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.119.14168 |

| [5] |

Kollias A, Dafni M, Poulidakis E, et al. Out-of-office blood pressure and target organ damage in children and adolescents:a systematic review and Meta-analysis[J]. J Hypertens, 2014, 32(12): 2315-2331. DOI:10.1097/HJH.0000000000000384 |

| [6] |

中国高血压防治指南修订委员会. 中国高血压防治指南2018年修订版[M]. 北京: 人民卫生出版社, 2018. Committee of Revision of Chinese Guidelines for Hypertension Prevention and Control. Chinese Guidelines for Hypertension Prevention and Treatment (2018 version)[M]. Beijing: People's Medical Publishing House, 2018. |

| [7] |

Flynn JT, Kaelber DC, Baker-Smith CM, et al. Clinical practice guideline for screening and management of high blood pressure in children and adolescents[J]. Pediatrics, 2017, 140(3). DOI:10.1542/peds.2017-1904 |

| [8] |

Sun JH, Steffen LM, Ma CW, et al. Definition of pediatric hypertension:are blood pressure measurements on three separate occasions necessary?[J]. Hypertens Res, 2017, 40(5): 496-503. DOI:10.1038/hr.2016.179 |

| [9] |

Lurbe E, Agabiti-Rosei E, Cruickshank JK, et al. 2016 European Society of Hypertension guidelines for the management of high blood pressure in children and adolescents[J]. J Hypertens, 2016, 34(10): 1887-1920. DOI:10.1097/HJH.0000000000001039 |

| [10] |

Outdili Z, Marti-Soler H, Bovet P, et al. Performance of blood pressure measurements at an initial screening visit for the diagnosis of hypertension in children[J]. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich), 2019, 21(9): 1352-1357. DOI:10.1111/jch.13645 |

| [11] |

Meng LH, Zhao D, Pan Y, et al. Validation of Omron HBP-1300 professional blood pressure monitor based on auscultation in children and adults[J]. BMC Cardiovasc Disord, 2016, 16: 9. DOI:10.1186/s12872-015-0177-z |

| [12] |

中华人民共和国国家卫生健康委员会.WS/T610-20187岁~18岁儿童青少年血压偏高筛查界值[S].北京: 中国标准出版社, 2018. National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China. WS/T 610-2018 Reference of screening for elevated blood pressure among children and adolescents aged 7-18 years[S]. Beijing: Standard Press of China, 2018. |

| [13] |

中华人民共和国国家卫生和计划生育委员会.WS/T456-2014学龄儿童青少年营养不良筛查[S].北京: 中国标准出版社, 2014. National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People's Republic of China. WS/T 456-2014 Screening standard for malnutrition of school-age children and adolescents[S]. Beijing: Standard Press of China, 2014. |

| [14] |

中华人民共和国国家卫生和计划生育委员会.WS/T586-2018学龄儿童青少年超重与肥胖筛查[S].北京: 中国标准出版社, 2018. National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People's Republic of China. WS/T 586-2018 Screening for overweight and obesity among school-age children and adolescents[S]. Beijing: Standard Press of China, 2018. |

| [15] |

Bovet P, Gervasoni JP, Ross AG, et al. Assessing the prevalence of hypertension in populations:are we doing it right?[J]. J Hypertens, 2003, 21(3): 509-517. DOI:10.1097/01.hjh.0000052473.40108.07 |

| [16] |

Koebnick C, Mohan Y, Li X, et al. Failure to confirm high blood pressures in pediatric care-quantifying the risks of misclassification[J]. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich), 2018, 20(1): 174-182. DOI:10.1111/jch.13159 |

| [17] |

Veloudi P, Blizzard CL, Srikanth VK, et al. Influence of blood pressure level and age on within-visit blood pressure variability in children and adolescents[J]. Eur J Pediatr, 2018, 177(2): 205-210. DOI:10.1007/s00431-017-3049-y |

| [18] |

孟玲慧, 董虹孛, 闫银坤, 等. 听诊法血压重复测量在儿童青少年高血压调查中的应用[J]. 中华高血压杂志, 2015, 23(6): 566-570. Meng LH, Dong HB, Yan YK, et al. Consecutive measurements by auscultation are necessary in epidemiological survey on hypertension in children and adolescents[J]. Chin J Hypertens, 2015, 23(6): 566-570. DOI:10.16439/j.cnki.1673-7245.2015.06.024 |

| [19] |

苑润滋, 王梅, 范超群, 等.拉萨市8~18岁儿童青少年血压现状研究[C]//第十一届全国体育科学大会论文摘要汇编.北京: 中国体育科学学会, 2019. Yuan RZ, Wang M, Fan CQ, et al. Blood pressure status among children and adoelscents aged 8-18 years in Lhasa[C]//Compilation of Paper Abstract from the 11th National Sports Science Congress. Beijing: China Sport Science Society, 2019. |

| [20] |

龚嘎蓝孜, 多吉卓玛, 央啦, 等. 不同海拔地区世居藏族青年血压及其影响因素分析[J]. 西藏大学学报:自然科学版, 2014, 29(2): 51-55. Gongga LZ, Duoji ZM, Yang L, et al. Analysis on the blood pressure and its impact factors among native Tibetan youth living at different altitudes[J]. J Tibet University:Natural Ed, 2014, 29(2): 51-55. DOI:10.16249/j.cnki.54-1034/c.2014.02.004 |

| [21] |

Mingji C, Onakpoya IJ, Perera R, et al. Relationship between altitude and the prevalence of hypertension in Tibet:a systematic review[J]. Heart, 2015, 101(13): 1054-1060. DOI:10.1136/heartjnl-2014-307158 |

2020, Vol. 41

2020, Vol. 41