文章信息

- 崔金朝, 聂陶然, 任敏睿, 刘凤凤, 李昱, 王丽萍, 谭吉宾, 常昭瑞, 李中杰.

- Cui Jinzhao, Nie Taoran, Ren Minrui, Liu Fengfeng, Li Yu, Wang Liping, Tan Jibin, Chang Zhaorui, Li Zhongjie

- 2008-2018年中国5岁及以下儿童手足口病死亡病例流行病学特征

- Epidemiological characteristics of fatal cases of hand, foot, and mouth disease in children under 5 years old in China, 2008-2018

- 中华流行病学杂志, 2020, 41(7): 1041-1046

- Chinese Journal of Epidemiology, 2020, 41(7): 1041-1046

- http://dx.doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn112338-20200114-00031

-

文章历史

收稿日期: 2020-01-14

2. 北京市密云区疾病预防控制中心 101500;

3. 中国疾病预防控制中心后勤运营管理中心, 北京 102206

2. Miyun District Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Beijing 101500, China;

3. Regular Operations Management Center, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Beijing 102206, China

手足口病(hand,foot,and mouth disease)是一种由多种肠道病毒引起的传染病,其主要病原有肠道病毒71型(EV-A71)和柯萨奇病毒A组16型(CV-A16),其中EV-A71为引起重症和死亡的主要病原。20世纪90年代以来,手足口病在新加坡、澳大利亚、马来西亚、日本、韩国等大规模流行,并有重症及死亡病例报道,是亚太地区重大公共卫生问题之一[1-2]。1981年我国上海市首次发现手足口病病例[3],此后在我国多地区陆续发现手足口病病例[4];2007年以来山东省临沂市、安徽省阜阳市和河南省商丘市先后出现手足口病暴发疫情,并出现重症和死亡病例[5-6]。2008年5月2日,手足口病被列入我国丙类传染病报告管理,而减少死亡病例的发生,降低病死率是手足口病防控的重点。2016年我国自主研发的EV-A71灭活疫苗上市[7],已有研究证实,全程接种疫苗对于EV-A71感染相关手足口病的保护效力>90%[8-11]。本研究通过分析2008-2018年我国手足口病死亡病例发生水平的变化趋势、空间和人群分布、引起死亡的可能影响因素,为减少死亡病例的发生,进一步完善我国手足口病防控策略提供重要参考依据。

资料与方法1.资料来源:中国CDC疾病监测信息报告管理系统,按照发病日期收集2008-2018年所有手足口病死亡病例个案信息,包括人口学特征、病例分类(临床与实验室诊断)、实验室检测结果、发病日期、诊断日期、死亡日期以及病例报告单位。死亡病例居住地城乡划分按照《统计用区划代码和城乡划分代码编制规则》(国统字〔2009〕91号),使用2018年国家统计局统计用代码进行区分。

手足口病病例诊断由各级各类医疗机构医务人员按照国家卫生健康颁布的手足口病诊疗指南和诊断标准中定义进行诊断[12-13],并通过网络直报系统上报中国CDC疾病监测信息报告管理系统。手足口病死亡病例是指手足口病病例中出现危重症状(中枢神经系统症状,脑膜炎、脑炎、脑脊髓炎,出现肺水肿、肺出血和/或循环功能障碍等)而最终死亡的病例。

按照《手足口病预防控制指南(2009版)》要求,对所有死亡病例进行标本采集及实验室检测。标本由接诊医院医务人员或辖区CDC人员采集,采集标本类型为咽拭子、粪便或者肛拭子,采集的标本及时运送至病例就诊医疗机构所在辖区地市级CDC(手足口病网络实验室)进行肠道病毒核酸检测,检测方法采用实时RT-PCR或RT-PCR方法,检测病原包括EV-A71、CV-A16及其他肠道病毒。

2.统计学方法:使用R 3.6.1软件对2008-2018年手足口病病例个案数据进行整理。采用Excel 2010软件进行描述流行病学分析,分析指标包括2008-2018年≤5岁儿童手足口病平均发病率、死亡率和病死率,其中病死率(/万)的计算:2008-2018年≤5岁儿童手足口病死亡数/同期≤5岁儿童手足口病病例数×10 000。

使用死亡率和病死率年度变化百分比(annual percentage change,APC)描述手足口病死亡病例随时间变化趋势。APC是一种可以用于描述疾病发病率、死亡率、病死率等时间变化的指标,假设在所研究的时间段内,疾病每年的发病率、死亡率、病死率按照固定的对数线性百分比上升或下降,并通过假设检验,确定APC是否有统计学意义。使用Join point 4.0.4软件,采用Age Adjusted Rate Calculation Session模型[14],对标化后的死亡率和病死率进行多阶段回归分析,计算APC,率的标化使用2018年中国各年龄段人口数作为标准人口。将各省份手足口病年度死亡病例按照2008-2010、2011-2013、2014-2016和2017-2018年分段汇总,使用Arc GIS Map 10.5软件绘制地图。

使用R 3.6.1软件,采用多元logistic回归模型,对实验室确诊病例中死亡病例和非死亡病例的人口学特征、病原检测情况、发病情况等方面进行分析,将性别、年龄、居住地、病原检测结果、发病诊断间隔共5个变量作为自变量X,是否死亡作为因变量Y,构建条件logistic回归模型进行分析,确定引起手足口病死亡的危险因素。

结果1.手足口病死亡病例变化趋势:2008-2018年全国共报告手足口病死亡病例3 668例,其中≤5岁儿童3 646例,≤5岁儿童死亡率35.34/10万,病死率1.79/万。死亡数、死亡率及病死率整体呈下降趋势,2010年报告死亡病例数最多(899例),病死率50.94/10万。以2010年为界,2008-2010年调整后的死亡率由0.13/10万上升至0.87/10万(APC=156.41%),病死率由35.12/10万上升至52.65/10万(APC=22.44%);2010-2018年调整后死亡率由0.87/10万下降至2018年的0.11/10万(APC=-23.20%),病死率由52.65/10万下降至3.41/10万(APC=-28.97%),下降趋势明显。见图 1。

|

| 图 1 2008-2018年全国手足口病死亡变化趋势 |

死亡病例中,男性2 355例,女性1 291例,性别比为1.82:1,各年度性别构成均男性高于女性,差异无统计学意义(图 2A)。年龄范围7 d~71月龄,M=19月龄,主要集中在≤2岁组(87.71%),1岁组人数最多(40.76%);不同年份年龄构成略有不同,2018年死亡病例均为0~3岁婴幼儿,其中1岁组仍占比最大,为57.14%(图 2B)。

|

| 图 2 2008-2018年全国手足口病死亡病例性别、年龄构成 |

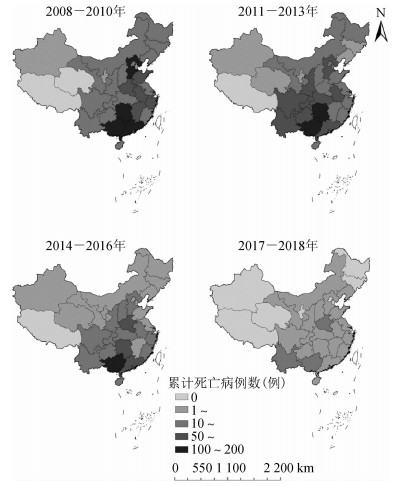

2.手足口病死亡病例空间分布及变化:除西藏自治区外,其余省份均有手足口病死亡病例报告,死亡率较高的省份为海南省、广西壮族自治区、湖南省、重庆市和广东省;病死率较高的省份为贵州省、黑龙江省、甘肃省、重庆市和河北省。死亡病例数>100例的省份由2008-2010年的4个省份(广东省、广西壮族自治区、湖南省和河北省)减少到2011-2013年的2个省份(广西壮族自治区和湖南省)和2014-2016年的1个省份(广西壮族自治区)。见图 3。

|

| 图 3 2008-2018年全国手足口病死亡病例地区分布 |

死亡病例数在50~例的省份由2008-2010年的5个省份(浙江省、安徽省、江西省、山东省和河南省)在2011-2013年上升至8个省份(河北省、安徽省、湖北省、重庆市、四川省、贵州省、云南省和陕西省),之后在2014-2016年下降至3个省份(河南省、湖南省和广东省)。死亡病例数为10~例的省份由2008-2010年的17个省份,降至2017-2018年的3个省份。而死亡数1~例的省份由2008-2010年3个省份,增至2017-2018年的19个省份。见图 3。

全国有2 530个区县报告了手足口病死亡病例,2010年最多(546个),随后报告区县数呈下降趋势,2018年全国仅有32个县有手足口病死亡病例报告。

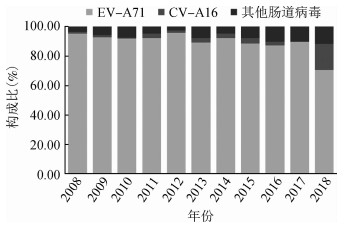

3.手足口病死亡病例病原学变化:2 523例实验室确诊死亡病例中,2 323例(92.07%)由EV-A71引起,49例(1.90%)为CV-A16,151例(6.03%)为其他肠道病毒。不同年份病原构成略有变化,各年度虽均以EV-A71为优势病原,但其他肠道病毒构成呈增加趋势,2018年CV-A16引起死亡病例构成明显增加,2015-2017年CV-A16构成比平均水平为2.14%,2018年构成比增加至17.65%(图 4)。

|

| 图 4 2008-2018年全国报告手足口病死亡病例病原分布 |

实验室确诊死亡病例中,不同年份不同病原引起的死亡病例年龄构成发生变化。2016年以来,由EV-A71引起的死亡病例年龄M(2016年:18月龄,2017年:19月龄,2018年:20月龄)逐年增加,CV-A16(2015年:36月龄,2016年:24月龄,2018年:19月龄)和其他肠道病毒(2016年:24月龄,2017年:11月龄,2018年:9月龄)导致的手足口病死亡病例年龄M逐年降低;2016年以来CV-A16和其他肠道病毒引起的死亡病例93.54%都在小年龄组(0~岁),高于往年。

4.手足口病死亡病例诊断情况:手足口病死亡病例发病至诊断时间间隔、发病至死亡时间间隔M=2(P25~P75:2~4)和3(P25~P75:2~4)d;不同病原引起的死亡病例发病与死亡时间间隔分布相似,均M=3(P25~P75:2~4)d;而发病至诊断时间间隔略有不同,EV-A71、其他肠道病毒和CV-A16引起的死亡病例发病至诊断时间间隔M=2(P25~P75:2~4)、2(P25~P75:2~3.5)和1(P25~P75:1~4)d。见图 5。

|

| 图 5 不同病原导致的手足口病死亡病例发病、诊断、死亡时间间隔分布 |

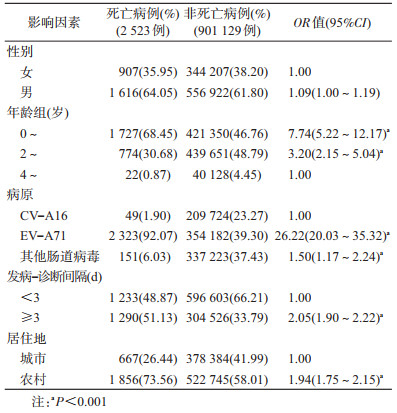

5.手足口病死亡病例危险因素分析:经多因素logistic回归分析,手足口病实验室确诊病例中死亡病例与非死亡病例的年龄、病原、发病诊断时间和居住地为农村或城市差异有统计学意义,低年龄、EV-A71感染、发病诊断时间延迟、居住地在农村为手足口病死亡危险因素(表 1)。

本研究采用全国法定报告传染病数据,描述了2008-2018年我国手足口病死亡病例流行病学特征。结果显示,手足口病死亡率总体呈下降趋势,死亡病例中男性多于女性,以≤2岁婴幼儿为主,重点地区为西南部和中部部分省份。EV-A71为手足口病死亡的主要病原体,其他肠道病毒和CV-A16感染有增加趋势。低龄、EV-A71感染、发病至诊断时间不及时、居住地在农村为手足口病死亡的危险因素。

2010年后,手足口病死亡率和病死率呈下降趋势,可能与以下原因有关。第一,手足口病非药物干预综合防控措施不断强化和落实,如病例的早期发现、诊断、报告和管理的加强,良好的个人卫生习惯的养成,重点场所环境卫生的改善以及健康宣教等措施的实施。第二,医疗救治规范化及医务人员对疾病认识的加深和救治水平的提高[15],各地设立重症病例定点救治医院,重症病例早期识别和医疗救治指导文件不断完善[16]。最后,2013年以来,引起我国手足口病病原中EV-A71构成比例减少,以CV-A6和CV-A10为主要病原的其他肠道病毒构成增加,而其他肠道病毒引起重症和死亡的比例较低。

人群特征分布显示,2008-2018年我国手足口病死亡病例中男性多于女性,年龄以≤2岁婴幼儿为主,与既往相关研究结果一致[17-18],提示低龄是手足口病死亡的危险因素,可能与EV-A71等肠道病毒抗体血清阳性率在低年龄组儿童中较低(1岁组儿童阳性率为24%)、人群普遍易感有关[19]。总体看来,死亡病例主要分布在西南部和中部部分省份,病死率较高的省份主要分布在西北地区的甘肃省、西南地区的贵州省和重庆市,提示相关省份应做好死亡病例从发病、诊断、救治及病原检测结果等相关环节的进一步分析,探索引起死亡的因素,寻找可干预环节,提出针对性干预措施,降低病死率。

既往研究报道,EV-A71是引起婴幼儿脑炎、脑膜炎、循环衰竭等重症并发症发生及死亡的重要病原[1, 20-21],本研究结果也提示EV-A71感染是引起死亡的危险因素。为降低EV-A71感染引起重症和死亡病例的发生,我国自2009年开始研发EV71型灭活疫苗,2016年EV71灭活疫苗已上市使用,Ⅲ期临床证实疫苗可有效预防EV-A71相关手足口病,对于EV-A71感染相关手足口病的保护效力>90%[8-10],说明对适龄儿童家庭进行EV-A71灭活疫苗宣传和接种是降低发病、减少死亡的有效措施。引起死亡病例的肠道病毒构成动态变化提示,CV-A16和其他肠道病毒导致病例的比例增加,建议加强重症和死亡病例病原学监测和临床特点研究,对引起死亡病例的其他肠道病毒进行分型,阐明引起手足口病死亡病例发生的病原谱及动态变化,并结合临床严重性,为医疗机构诊治及手足口病多价疫苗研发优先性提供知识和依据。

本研究存在局限性。首先,本研究数据为被动监测数据,报告质量受就诊行为习惯、医疗卫生资源可及性、病例诊断报告能力等因素影响,存在一定的漏报和误报,法定报告传染病系统整体漏报率约为5%[22-25],加上存在手足口病本身为自限性疾病,存在轻症病例不去医院就诊等情况,使得报告情况低于真实发病强度[26]。其次,本研究未能对所有死亡病例进行实验室检测,且无法掌握EV-A71和CV-A16以外引起手足口病患者死亡的其他肠道病毒血清型及临床严重程度。最后,死亡病例危险因素分析中未能纳入临床症状及医疗救治中可能的引起死亡的危险因素,还需进一步研究收集病例临床症状及医疗救治中相关生理生化指标的变化及异常值,揭示引起死亡病例发生的其他因素。

综上所述,我国手足口病死亡病例数和病死率总体呈现下降趋势,患儿年龄小、EV-A71感染、在农村居住、诊断救治延迟,仍是引起手足口病死亡的危险因素,建议在重点地区、重点人群中开展EV-A71灭活疫苗接种宣传、提高诊断与救治及时性等措施。由于引起手足口病的肠道病毒有20多种,死亡病例中EV-A71和CV-A16以外的其他肠道病毒构成升高,因此需加强病原学监测,为多价疫苗的研发提供依据。

利益冲突 所有作者均声明不存在利益冲突

| [1] |

Solomon T, Lewthwaite P, Perera D, et al. Virology, epidemiology, pathogenesis, and control of enterovirus 71[J]. Lancet Infect Dis, 2010, 10(11): 778-790. DOI:10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70194-8 |

| [2] |

Ooi MH, Wong SC, Lewthwaite P, et al. Clinical features, diagnosis, and management of enterovirus 71[J]. Lancet Neurol, 2010, 9(11): 1097-1105. DOI:10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70209-X |

| [3] |

Zheng ZM, He PJ, Caueffield D, et al. Enterovirus 71 isolated from China is serologically similar to the prototype E71 BrCr strain but differs in the 5'-noncoding region[J]. J Med Virol, 1995, 47(2): 161-167. DOI:10.1002/jmv.1890470209 |

| [4] |

邵惠训. 手足口病的现状与展望[J]. 国际病毒学杂志, 2010, 17(3): 74-78. Shao HX. Status and prospect of hand, foot and mouth disease[J]. Int J Virol, 2010, 17(3): 74-78. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1673-4092.2010.03.003 |

| [5] |

McMinn PC. An overview of the evolution of enterovirus 71 and its clinical and public health significance[J]. FEMS Microbiol Rev, 2002, 26(1): 91-107. DOI:10.1111/j.1574-6976.2002.tb00601.x |

| [6] |

Cheng H, Zeng JJ, Li HJ, et al. Neuroimaging of HFMD infected by EV71[J]. Radiol Infect Dis, 2015, 1(2): 103-108. DOI:10.1016/j.jrid.2015.02.006 |

| [7] |

中国疾病预防控制中心. 肠道病毒71型灭活疫苗使用技术指南[J]. 中国病毒病杂志, 2016, 6(4): 241-247. Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidelines for use of inactivated enterovirus type 71 vaccine[J]. Chin J Viral Dis, 2016, 6(4): 241-247. DOI:10.16505/j.2095-0136.2016.04.001 |

| [8] |

Li RC, Liu LD, Mo ZJ, et al. An inactivated enterovirus 71 vaccine in healthy children[J]. N Engl J Med, 2014, 370(9): 829-837. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa1303224 |

| [9] |

Zhu FC, Xu WB, Xia JL, et al. Efficacy, safety, and immunogenicity of an enterovirus 71 vaccine in China[J]. N Engl J Med, 2014, 370(9): 818-828. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa1304923 |

| [10] |

Zhu FC, Meng FY, Li JX, et al. Efficacy, safety, and immunology of an inactivated alum-adjuvant enterovirus 71 vaccine in children in China:a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial[J]. Lancet, 2013, 381(9882): 2024-2032. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61049-1 |

| [11] |

Hu YM, Wang X, Wang JZ, et al. Immunogenicity, safety, and lot consistency of a novel inactivated enterovirus 71 vaccine in Chinese children aged 6 to 59 months[J]. Clin Vacc Immunol, 2013, 20(12): 1805-1811. DOI:10.1128/CVI.00491-13 |

| [12] |

国家卫生健康委员会. 手足口病诊疗指南(2018年版)[J]. 传染病信息, 2018, 31(3): 193-198. National Health Commission. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of hand, foot and mouth disease (2018 edition)[J]. Infect Dis Inf, 2018, 31(3): 193-198. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1007-8134.2018.03.001 |

| [13] |

中华人民共和国国家卫生和计划生育委员会. WS 588-2018手足口病诊断[J]. 中国病毒病杂志, 2018, 8(6): 427-433. National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People's Republic of China. WS 588-2018 Diagnosis for hand, foot and mouth disease[J]. Chin J Viral Dis, 2018, 8(6): 427-433. DOI:10.16505/j.2095-0136.2018.0086 |

| [14] |

Kim HJ, Fay MP, Feuer EJ, et al. Permutation tests for joinpoint regression with applications to cancer rates[J]. Stat Med, 2000, 19(3): 335-351. DOI:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(20000215)19:3<335:aid-sim336>3.0.co;2-z |

| [15] |

钱素云, 李兴旺. 我国手足口病流行及诊治进展十年回首[J]. 中华儿科杂志, 2018, 56(5): 321-323. Qian SY, Li XW. Review of the hand-foot-mouth disease epidemic, diagnosis and treatment progress in China in ten years[J]. Chin J Pediatr, 2018, 56(5): 321-323. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0578-1310.2018.05.001 |

| [16] |

卫生部手足口病临床专家组. 肠道病毒71型(EV71)感染重症病例临床救治专家共识[J]. 中华儿科杂志, 2011, 49(9): 675-678. Expert Group of Hand, Foot and Mouth Disease, Ministry of Health. Expert consensus on clinical treatment of severe cases of enterovirus 71(EV71) infection[J]. Chin J Pediatr, 2011, 49(9): 675-678. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0578-1310.2011.09.007 |

| [17] |

常昭瑞, 张静, 孙军玲, 等. 中国2008-2009年手足口病报告病例流行病学特征分析[J]. 中华流行病学杂志, 2011, 32(7): 676-680. Chang ZR, Zhang J, Sun JL. Epidemiological features of hand, foot and mouth disease in China, 2008-2009[J]. Chin J Epidemiol, 2011, 32(7): 676-680. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2011.07.009 |

| [18] |

Koh WM, Bogich T, Siegel K, et al. The epidemiology of hand, foot and mouth disease in Asia:a systematic review and analysis[J]. Pediatr Infect Dis J, 2016, 35(10): E285-300. DOI:10.1097/inf.0000000000001242 |

| [19] |

Yang BY, Wu P, Wu JT, et al. Seroprevalence of enterovirus 71 antibody among children in China:a systematic review and Meta-analysis[J]. Pediatr Infect Dis J, 2015, 34(12): 1399-1406. DOI:10.1097/inf.0000000000000900 |

| [20] |

Hsu CH, Lu CY, Shao PL, et al. Epidemiologic and clinical features of non-polio enteroviral infections in northern Taiwan in 2008[J]. J Microbiol Immunol Inf, 2011, 44(4): 265-273. DOI:10.1016/j.jmii.2011.01.029 |

| [21] |

Wu CY, Wang KT, Weng SC, et al. Neutralization of five subgenotypes of Enterovirus 71 by Taiwanese human plasma and Taiwanese plasma derived intravenous immunoglobulin[J]. Biologicals, 2013, 41(3): 154-157. DOI:10.1016/j.biologicals.2013.02.002 |

| [22] |

金丽珠, 葛辉, 杜雪杰, 等. 2015年全国医疗机构法定传染病报告质量调查分析[J]. 疾病监测, 2016, 31(10): 883-886. Jin LZ, Ge H, Du XJ, et al. Reporting quality of notifiable communicable diseases in hospitals in China, 2015[J]. Dis Surveill, 2016, 31(10): 883-886. DOI:10.3784/j.issn.1003-9961.2016.10.019 |

| [23] |

郭青, 苏雪梅, 王晓风, 等. 2013年全国医疗机构法定传染病报告率调查分析[J]. 中华疾病控制杂志, 2015, 19(7): 683-687. Guo Q, Su XM, Wang XF, et al. Assessment on reporting rate of notifiable infectious diseases in hospitals in China, 2013[J]. Chin J Dis Control Prev, 2015, 19(7): 683-687. DOI:10.16462/j.cnki.zhjbkz.2015.07.010 |

| [24] |

王丽萍, 郭岩, 郭青, 等. 2006年全国法定传染病网络报告信息质量评价[J]. 疾病监测, 2007, 22(6): 412-414. Wang LP, Guo Y, Guo Q, et al. Quality evaluation of infectious diseases information based on internet reporting system in 2006[J]. Dis Surveill, 2007, 22(6): 412-414. DOI:10.3784/j.issn.1003-9961.2007.06.020 |

| [25] |

李言飞, 张业武, 王晓风, 等. 2005-2017年全国法定传染病重复报告卡大数据分析与应用[J]. 疾病监测, 2019, 34(5): 468-472. Li YF, Zhang YW, Wang XF, et al. Application of big data in analysis of duplicate reporting cards in national notifiable disease report system, 2005-2017[J]. Dis Surveill, 2019, 34(5): 468-472. DOI:10.3784/j.issn.1003-9961.2019.05.021 |

| [26] |

张静. 2008-2017年中国手足口病流行趋势和病原变化动态数列分析[J]. 中华流行病学杂志, 2019, 40(2): 147-154. Zhang J. Trend of epidemics and variation of pathogens of hand, foot and mouth disease in China:a dynamic series analysis, 2008-2017[J]. Chin J Epidemiol, 2019, 40(2): 147-154. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2019.02.005 |

2020, Vol. 41

2020, Vol. 41