文章信息

- 尚翠, 张全福, 殷强玲, 李德新, 李建东.

- Shang Cui, Zhang Quanfu, Yin Qiangling, Li Dexin, Li Jiandong

- 汉坦病毒病流行影响因素分析

- Influence factors related epidemics on hantavirus disease

- 中华流行病学杂志, 2020, 41(6): 968-974

- Chinese Journal of Epidemiology, 2020, 41(6): 968-974

- http://dx.doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn112338-20190916-00678

-

文章历史

收稿日期: 2019-09-16

汉坦病毒(hantaviruses,HV)是基因组分节段的单股负链RNA病毒,属布尼亚病毒目(Bunyavirales)HV(Hantaviridae)的正HV属(Orthohantavirus)[1]。HV病在亚洲、欧洲、非洲和美洲均有分布[2],在一些地区呈地方性流行,病例发生具有季节性,并呈现一定周期性。根据疾病临床表现可分为肾综合征出血热(hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome,HFRS)和肺综合征出血热(hantavirus pulmonary syndrome,HPS),疾病严重程度主要取决于引发疾病的病原体[3]。HFRS主要分布于亚、欧大陆,非洲也有病例报告,中国是HFRS报告病例最多的地区[4-5],在亚洲,HFRS主要由汉滩病毒(hantaan virus,HTNV)和汉城病毒(Seoul virus,SEOV)感染引起,HTNV感染病例病死率可达5%~10%,SEOV感染病例临床表现较轻,病死率约为1% [6-7];普马拉病毒(Puumala virus,PUUV)和多布拉伐-贝尔格莱德病毒(Dobrava-Belgrade virus,DOBV)是欧洲引起HFRS的主要病原,PUUV感染病死率低于1%,而DOBV感染患者病死率可达15%。HPS发病局限于美洲地区,自1993年以来,累计报告病例约4 000多例,病例病死率可高达50%[8]。

近年来,随着经济社会的加速发展,气候环境的显著变化,全球范围内新的疫点不断出现,一些沉寂了多年的老疫点再燃,发病数波动上升。同时,多种新的HV被发现,但其临床及公共卫生意义有待进一步明确。有学者提出影响人兽共患病的流行与传播的因素主要包括影响宿主动物繁殖和种群密度的环境因素;影响或破坏生态系统复杂性的人为因素;影响病原排出的遗传因素;个体行为因素,如争斗或共享等;影响宿主感染的生理因素等[9]。本研究系统检索已发表的科技文献,对影响HV传播和感染的影响因素进行归纳总结,以期为科学防控HV,提前落实针对性预防控制措施提供依据。

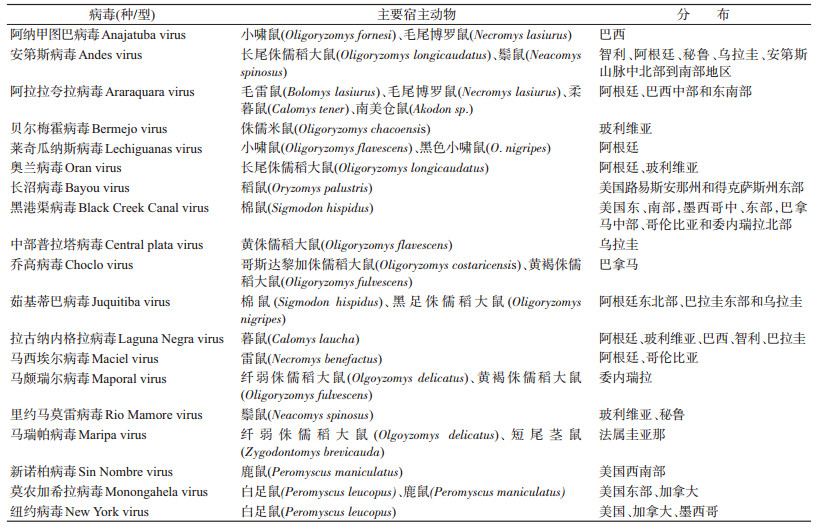

一、病毒与宿主HV和宿主动物流行病学分布特征及其间相互作用是决定HV病发生的关键因素。自1978年首次分离HTNV以来[10],不断有新的HV被发现,至2018年,国际病毒学分类委员会认定的可感染哺乳动物HV有36种。每种HV一般有一种主要宿主,也可存在几种密切相关的宿主动物[7]。对人致病的HV多以仓鼠科(Circetidae)和鼠科(Muridae)中啮齿类动物为宿主,病毒基因组遗传进化分析形成3个主要的进化分支,可反映相应啮齿类宿主动物的分类,对应为鼠亚科(Murinae)、田鼠亚科(Arvicolinae)和棉鼠亚科/木鼠亚科(Sigmodontinae/Neotominae)分支,提示存在病毒宿主动物共进化的关系[1, 11-12]。引发HFRS的HV主要以鼠亚科和田鼠亚科动物为宿主(表 1),鼠亚科动物携带致人类疾病的HV主要包括HTNV、SEOV、DOBV、萨雷玛病毒(Saaremaa virus,SAAV)等。田鼠亚科携带HV主要有PUUV、图拉病毒(Tula virus,TULV)等可引起轻症HFRS的病毒,也包括中国、日本、韩国等地发现的临床和公共卫生意义尚不明确的茂朱病毒(Muju virus)等普马拉类病毒。棉鼠亚科和木鼠亚科啮齿类动物携带HV主要分布在北美和南美地区,如辛诺柏病毒(Sin Nombre virus,SNV)、牛轭湖病毒(Bayou virus,BAYV)、安第斯病毒(Andes virus,ANDV)和黑岗渠病毒(Black Creek Canal orthohantavirus,BCCV)等(表 2)。

除啮齿动物外,鼩鼱、鼹鼠和蝙蝠均可充当HV的宿主,病毒在宿主动物体内可以形成持续性感染[13],但源自鼩鼱类动物的病毒株,病毒进化与宿主的对应关系并不明显[14],可能是宿主动物转换、局部适应和共进化等因素共同作用的结果。节肢动物中也发现有多种HV,但尚未发现经虫媒叮咬后传播HV的证据。

HV为RNA病毒,具有较高的变异率,导致病毒基因组的多样性。在自然界宿主动物中和实验室病毒培养过程中均有准种(quasi-species)存在,但其对病毒遗传多样性的影响尚缺少定量的研究。在同一宿主动物中,准种或不同种病毒同时存在可导致病毒适应性进化,导致重组或重排的发生。研究发现PUUV、SNV、ANDV、HNTV和DBOV等病毒可在实验室和自然条件下发生重排,但并非随机性重排,多发于M基因[15-20]。研究还发现,HTNV和SEOV在自然状态下发生种间重排[21],TULV S片段发生种内重组现象[22],提示在合适的条件下,HV种内和种间重排,以及重组均可发生,可能是HV多样性和遗传进化的重要来源,但尚无明显证据揭示哪些变化可影响病毒的病原学特征,从而产生显著公共卫生学意义。

宿主的易感性也对HV的感染、流行发挥重要影响。啮齿类动物的主要组织相容性复合体(Major histocompatibility complex,MHC)与HV感染易感性有关,或是影响病毒地理分布的重要因素之一[23],不能排除存在对HV天然不易感的啮齿类动物种群。一般认为,啮齿动物的带毒率和密度反映了其对HV病的传播能力,与人群HFRS感染率在时间和空间上均呈现正相关关系,可能是增加了与人群的接触机会和感染机会[24-25]。

人类感染主要是通过吸入或直接接触带有传染性病毒的宿主动物排泄或分泌物而感染[26],个体之间存在HV易感性差异,与个体免疫遗传因素有关,人白细胞抗原(human leukocyte antigen,HLA)或肿瘤坏死因子(tumor necrosis factor,TNF)多态性,影响病毒易感性和发病严重程度[27-28],中国带有HLA-B*46-DRB1*09和HLA-DRB1*09的汉族人对HNTV易感[29],而带有HLA-B*08单倍体型的人感染ANDV则容易发展为重症[30],TNF-α、血小板糖蛋白多态性与HV病严重程度有关[31-33]。人群对HFRS普遍易感,主要与感染性物质接触机会有关,如农民、露营者、牧羊人、护林员等属高危人群。人群对HV病抵抗程度是由免疫水平决定的,随着集体免疫水平的提高,特定疾病(HFRS)的发病率、死亡率和致死率均呈下降趋势,反之亦然。1986年,科索沃HFRS的病死率为15.4%,1986-1989年为10.8%,1995-2006年为8.70%,研究认为是集体免疫增长的结果[34]。

二、气候与气象因素气候与气象因素是自然疫源性疾病发生、扩散的重要影响因素,但其作用机制是十分复杂的,这也给相关的定性、定量的影响因素分析研究带来困难,不同地区基于特定区域气候与气象单因素对病毒传播的影响研究结果不尽相同[35-36]。总体来说,气候与气象因素变化,可对宿主动物食物供给和生存环境产生影响,导致啮齿类宿主动物的种群密度和生活习性改变,从而影响人类与受感染宿主动物或其污染物的接触机会和方式,影响疫情发生的规模[37]。研究较多的影响因素有温度、湿度和降雨量等与HFRS和HPS的传播关系[38-39],主要是通过影响宿主动物密度、与病毒相互作用,以及人类的活动而实现的。

关于温度的影响,在欧洲中西部地区的研究表明,PUUV感染引发流行性肾病(Epidemic nephropathy,NE)暴发与前2年夏季和前1年秋季平均气温的升高呈正相关关系,研究者认为温度增高可促进植物生长与种子产量,为啮齿类动物提供了充足食物和庇护所,促进啮齿类动物繁殖与生存,种群密度提高,导致人群感染风险增加[40-41]。在中国黑龙江、重庆、陕西、北京等地区开展研究提示温度对HFRS流行影响效果并不一致[38, 42-44],这固然与所选择的度量指标和方法的不同有关,也应受这些地区本底气候与气象条件差异显著的影响。温度可能通过妊娠数、产仔数、出生率和存活率来影响啮齿动物种群密度[41],温和的温度(10 ℃~25 ℃)更有利于啮齿类动物繁殖[45]。冬季较低温度可减少啮齿动物的生长,较高温度可能使其在冬季更容易存活,传染性啮齿动物的密度越大时,人类与其之间的接触机会就越大,发生疾病风险增加[46]。温度对疾病传播影响的风险存在阈值,这个阈值可能是一个点或区间,不同研究认为17 ℃左右或6 ℃~23.7 ℃,当温度低于点阈值或在区间阈值之外时,HFRS发生与温度呈正相关[47-49]。也有研究发现,极端温度或湿度可促进HFRS流行[49],或许与极端气候与气象条件破坏宿主动物栖息环境增加与人类的接触有关。

湿度也是HV病发病的重要影响因素,HFRS的年发病率与年降水量、年平均绝对湿度呈正相关[50],温度和降水还会对HV在环境中的生存能力以及其侵染性产生影响[51-53]。有研究者认为,1993年美国四角地区暴发的HPS疫情与1992-1993年美国发生的厄尔尼诺现象(El Nino-Southern Oscillation,ENSO)降水量急剧增加有关[39]。高降水量增加了植被的生长,增加了啮齿动物的密度,人类与受感染的啮齿动物接触的可能性增加,从而促进了HV的传播。有中国学者发现,HFRS月发病数与降水呈显著相关,降雨量增加1 mm,HFRS病例增加0.2%,滞后期为5个月;如果大量降水产生洪水,可淹没啮齿动物巢穴,破坏栖息地或造成鼠密度下降,减少与人类接触机会从而降低病毒传播的可能性[50, 54],也存在啮齿类动物因洪灾而向高处迁移或逃入人类居住环境则有导致病毒传播增加的可能。据记载,1954、1975和1991年中国部分地区发生了3次特大洪涝灾害,报告病例数分别较上一年上升了60.0%、22.75%和21.6%[55]。在严重干旱的条件下,鼠类可能向居民区迁移,致使室内鼠密度增高,引起人间疫情暴发[56]。虽然气候与气象条件对HV传播的精准影响仍需要进一步探索,但在气候与气象发生显著变化后,积极采取干预措施,可预防HV病疫情暴发。

三、地理环境因素HV病疫源地的维持受啮齿动物栖息地的地理环境影响,与宿主动物种群密度、病毒流行程度、啮齿动物的多样性、啮齿动物群落组成和物种分布有关[57-58]。

森林是媒介生物或宿主种群的主要栖息地,在过去的一个世纪里,地貌发生了巨大改变,每年有1.3×107公顷的森林被毁[59],导致生物多样性丧失严重,热带雨林地区每年可能有1.4万~4.0万个物种消失[60]。有研究指出,物种多样性增加可降低传染病的患病率,这种现象被称为稀释效应[61],可能的机制是其他物种的存在可能会改变啮齿类动物的行为、运动或发育,物种多样性提高还相对降低了种内偶遇率,但并没有减少接触持续时间[61],生物多样性可缓冲HV传播的强度,有研究人员发现在SNV和PUUV传播扩散过程中存在稀释效应影响[62-63]。人类的干扰常常造成生境碎片化,可影响啮齿动物生存环境,从而影响HV的传播[64-65]。大型的工程建设比如高速公路、铁路、地铁、机场、水库等的修建,都可改变啮齿类动物生境,啮齿动物为了觅食和逃避生境的破坏,它们会逐步迁移到适宜的地方生存,导致鼠种构成发生显著性变化,影响人群与宿主的接触机会[66]。城市化进程加快,农场、牧场不断扩大,已成为地球上最大的陆地生物群落栖息地,占据陆地表面的40%[67],增加了HV等自然疫源性疾病的传播风险[68]。农田和一些经济作物种植面积增大,可形成宿主偏爱的栖息地[69-70],造成鼠密度升高,导致病毒感染风险增加,调查发现,农业地区啮齿类动物HV感染率高于野生环境[71]。自然植被覆盖对啮齿动物的丰度和感染率有正向影响,可能由于啮齿动物对食物和住所的需要有关,HV病风险较高的地区多为植被覆盖度较高的地区,土地植被和利用方式变化曾引起多起HV病疫情的暴发[72],在巴西,因甘蔗种植面积不断扩大,使20%的人口面临感染HPS的平均风险提高1.5%[73]。

四、经济和社会因素人感染HV的风险最终取决于人与病毒感染的宿主动物或其排泄物的接触,因此,人类的生产、生活方式及行为习惯是影响HV病流行的决定性因素。在发生的人类感染病例中以中年男性居多,农民所占的比例在所有职业中最高,性别、年龄和职业分布的差异很可能是由于接触受感染的啮齿动物及其排泄物的机会不同造成的。农林业相关的翻耕、灌溉、收割、储存、狩猎等活动也是最重要的危险因素[74]。人类的战争期间,大量军队在野外驻扎,为HV的传播提供条件。在侵华日军中以及第一次世界大战和第二次世界大战期间的欧洲战场均发现HV感染的广泛存在[75]。朝鲜战争期间数千名士兵感染HV,引起高度重视[76]。有调查发现,吸烟是PUUV感染的一个重要的危险因素[77],可能与吸烟促进气溶胶吸入或增加手口接触频次有关。

经济发展和人类社会活动对传染病的发生、扩散、预防与控制发挥极其重要的作用。一方面,大规模的土地改造,基础设施建设,生产关系的短时间内巨大改变都可能导致HV病等自然疫源性疾病发病率上升。20世纪50年代,新中国成立不久,一元复始,万象更新,全国掀起经济建设的高潮,但随着农田基础建设的广泛展开,HFRS发病率显著上升,1955年在大兴安岭图里河地区、1956年在陕西省秦岭北麓均发生了大规模的暴发疫情,全国范围内新的疫区、疫点不断被发现,引起政府和社会公众高度重视,将出血热定为法定报告乙类传染病和重点防治疾病。20世纪80年代初,中国持续十余年的HFRS高发,或许与国家大力推行联产承包责任制和大包干制度,极大提高了农民生产积极性和土地利用率,有一定的关系。全球范围内,城市化建设、森林砍伐、灌溉工程和道路建设引起HV病疫情暴发屡有报道。另一方面,经济发展,社会进步,生活条件和卫生状况改善,人与啮齿类动物及其排泄物接触机会降低,减少疾病的传播,降低发病率[78-79]。卫生保健服务的改善,人们对疾病预防和控制的认识提高,推动个体行为改变,也是显著降低传染病传播风险的关键。在中国,自20世纪90年代开始,在重点人群实施免疫接种计划,2008年开始实施扩大免疫规划,在重点地区针对重点人群,对HFRS疫情防控和个体保护方面产生显著效果[80]。

五、结语HV病流行是病毒、宿主动物和个体人之间的相互作用的结果,取决于病毒感染宿主动物、啮齿动物密度、适宜病毒在环境中维持的气候条件、易感人群和人与环境中病毒的接触机会等因素,受温度、湿度和降水等气候与气象条件,地理环境因素,以及经济社会发展因素等影响,各因素之间交互作用,而非独立作用。在这个疾病传播动态过程中,宿主动物在HFRS流行中起主导作用,但如果温度条件不适合病毒存活和气溶胶化,也不会发生传染给人类的事件,因此,病毒在宿主外存活的能力对于在啮齿动物种群内和人间的传播至关重要,啮齿动物存在和丰富程度并不一定意味着疾病的传播。被感染的宿主动物数量少,或宿主动物种群密度低,导致病毒难以在动物种群中扩散,也是影响疾病传播的重要因素。

多年来,中国HFRS防治工作全面推行以防鼠灭鼠、重点人群预防接种为主的综合防治策略,取得了较好的防控效果,疫情持续多年保持低发状态。随着中国经济社会高速发展,公共卫生服务体系日益完善,全国全面进入小康社会,HFRS将得以有效控制,但这个过程会出现波动,甚至疫情反弹,尤其是当前全面展开的新时代乡村建设过程中,人与自然接触增加,会出现HFRS发病增加的现象。同时,在全球气候变暖的总趋势下,局部地区气候与气象剧烈变化,环境生态重建与破坏同时并生,为HV病流行带来不确定性。应积极采取措施,加强流行地区人间疫情与啮齿宿主动物监测与控制,做好重点人群免疫接种和健康教育工作,有效控制HV病。积极推动大数据、人工智能技术在HFRS防控领域的应用,建立预测评估模型,量化环境、啮齿动物、病毒和人类疾病发生之间的关系,也是指导防控措施落实的有效手段。

利益冲突 所有作者均声明不存在利益冲突

| [1] |

Plyusnin A, Vapalahti O, Vaheri A. Hantaviruses:genome structure, expression and evolution[J]. J Gen Virol, 1996, 77(11): 2677-2687. DOI:10.1099/0022-1317-77-11-2677 |

| [2] |

Bi ZQ, Formenty PBH, Roth CE. Hantavirus infection:a review and global update[J]. J Infect Dev Country, 2008, 2(1): 3-23. DOI:10.3855/jidc.317 |

| [3] |

Jonsson CB, Figueiredo LTM, Vapalahti O. A global perspective on hantavirus ecology, epidemiology, and disease[J]. Clin Microbiol Rev, 2010, 23(2): 412-441. DOI:10.1128/CMR.00062-09 |

| [4] |

Zhang YZ, Zou Y, Fu ZF, et al. Hantavirus Infections in Humans and Animals, China[J]. Emerg Infect Dis, 2010, 16(8): 1195-1203. DOI:10.3201/eid1608.090470 |

| [5] |

Kariwa H, Yoshimatsu K, Arikawa J. Hantavirus infection in East Asia[J]. Comp Immunol Microb Infect Dis, 2007, 30(5/6): 341-356. DOI:10.1016/j.cimid.2007.05.011 |

| [6] |

Hooper JW, Larsen T, Custer DM, et al. A lethal disease model for hantavirus pulmonary syndrome[J]. Virology, 2001, 289(1): 6-14. DOI:10.1006/viro.2001.1133 |

| [7] |

Vapalahti PO, Mustonen J, Lundkvist Å, et al. Hantavirus Infections in Europe[J]. Lancet Infect Dis, 2003, 3(10): 653-661. DOI:10.1016/S1473-3099(03)00774-6 |

| [8] |

Figueiredo LTM, de Souza WM, Ferrés M, et al. Hantaviruses and cardiopulmonary syndrome in South America[J]. Virus Res, 2014, 187: 43-54. DOI:10.1016/j.virusres.2014.01.015 |

| [9] |

Mills JN. Regulation of Rodent-Borne viruses in the natural host:implications for human disease[J]. Arch Virol Suppl, 2005(19): 45-57. DOI:10.1007/3-211-29981-5_5 |

| [10] |

Lee HW, Lee PW, Johnson KM. Isolation of the etiologic agent of Korean Hemorrhagic fever[J]. J Infect Dis, 1978, 137(3): 298-308. DOI:10.1093/infdis/137.3.298 |

| [11] |

Klempa B, Schmidt HA, Ulrich R, et al. Genetic interaction between distinct dobrava hantavirus subtypes in Apodemus agrarius and A. flavicollis in Nature[J]. J Virol, 2003, 77(1): 804-809. DOI:10.1128/JVI.77.1.804-809.2003 |

| [12] |

Wang H, Yoshimatsu K, Ebihara H, et al. Genetic diversity of hantaviruses isolated in China and characterization of novel hantaviruses isolated from Niviventer confucianus and Rattus rattus[J]. Virology, 2000, 278(2): 332-345. DOI:10.1006/viro.2000.0630 |

| [13] |

Childs JE, Mackenzie JS, Ric JA. Wildlife and emerging zoonotic diseases: the biology, circumstances and consequences of cross-species transmission[M]. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer, 2007.

|

| [14] |

Ramsden C, Melo FL, Figueiredo LM, et al. High rates of molecular evolution in hantaviruses[J]. Mol Biol Evol, 2008, 25(7): 1488-1492. DOI:10.1093/molbev/msn093 |

| [15] |

Klempa B. Hantaviruses and climate change[J]. Clin Microbiol Infect, 2009, 15(6): 518-523. DOI:10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.02848.x |

| [16] |

Medina RA, Torres-Perez F, Galeno H, et al. Ecology, genetic diversity, and phylogeographic structure of andes virus in humans and rodents in Chile[J]. J Virol, 2009, 83(6): 2446-2459. DOI:10.1128/JVI.01057-08 |

| [17] |

Razzauti M, Plyusnina A, Henttonen H, et al. Accumulation of point mutations and reassortment of genomic RNA segments are involved in the microevolution of Puumala hantavirus in a bank vole (Myodes glareolus) population[J]. J Gen Virol, 2008, 89(7): 1649-1660. DOI:10.1099/vir.0.2008/001248-0 |

| [18] |

Razzauti M, Plyusnina A, Sironen T, et al. Analysis of Puumala hantavirus in a bank vole population in northern Finland:evidence for co-circulation of two genetic lineages and frequent reassortment between strains[J]. J Gen Virol, 2009, 90(8): 1923-1931. DOI:10.1099/vir.0.011304-0 |

| [19] |

Zou Y, Hu J, Wang ZX, et al. Molecular diversity and phylogeny of Hantaan virus in Guizhou, China:evidence for Guizhou as a radiation center of the present Hantaan virus[J]. J Gen Virol, 2008, 89(8): 1987-1997. DOI:10.1099/vir.0.2008/000497-0 |

| [20] |

Iv WCB, Doty JB, Hughes MT, et al. Temporal and geographic evidence for evolution of Sin Nombre virus using molecular analyses of viral RNA from Colorado, New Mexico and Montana[J]. Virol J, 2009, 6(1): 102. DOI:10.1186/1743-422X-6-102 |

| [21] |

Zou Y, Hu J, Wang ZX, et al. Genetic characterization of hantaviruses isolated from Guizhou, China:evidence for spillover and reassortment in nature[J]. J Med Virol, 2008, 80(6): 1033-1041. DOI:10.1002/jmv.21149 |

| [22] |

Sibold C, Meisel H, Krüger DH, et al. Recombination in Tula Hantavirus Evolution:Analysis of Genetic Lineages from Slovakia[J]. J Virol, 1999, 73(1): 667-675. DOI:10.1128/JVI.73.1.667-675.1999 |

| [23] |

Deter J, Bryja J, Chaval Y, et al. Association between the DQA MHC class Ⅱ gene and Puumala virus infection in Myodes glareolus, the bank vole[J]. Infect Genet Evol, 2008, 8(4): 450-458. DOI:10.1016/j.meegid.2007.07.003 |

| [24] |

Olsson GE, White N, Hjältén J, et al. Habitat factors associated with bank voles (Clethrionomys glareolus) and concomitant hantavirus in northern Sweden[J]. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis, 2005, 5(4): 315-323. DOI:10.1089/vbz.2005.5.315 |

| [25] |

Olsson GE, Dalerum F, Hörnfeldt B, et al. Human hantavirus infections, Sweden[J]. Emerg Infect Dis, 2003, 9(11): 1395-1401. DOI:10.3201/eid0911.030275 |

| [26] |

Forbes KM, Sironen T, Plyusnin A. Hantavirus maintenance and transmission in reservoir host populations[J]. Curr Opin Virol, 2018, 28: 1-6. DOI:10.1016/j.coviro.2017.09.003 |

| [27] |

Mäkelä S, Mustonen J, Ala-Houhala I, et al. Human leukocyte antigen-B8-DR3 is a more important risk factor for severe Puumala hantavirus infection than the tumor necrosis factor-α(-308) G/A polymorphism[J]. J Infect Dis, 2002, 186(6): 843-846. DOI:10.1086/342413 |

| [28] |

Mustonen J, Partanen J, Kanerva M, et al. Genetic susceptibility to severe course of nephropathia epidemica caused by Puumala hantavirus[J]. Kidney Int, 1996, 49(1): 217-221. DOI:10.1038/ki.1996.29 |

| [29] |

Wang ML, Lai JH, Zhu Y, et al. Genetic susceptibility to haemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome caused by Hantaan virus in Chinese Han population[J]. Int J Immunogenet, 2009, 36(4): 227-229. DOI:10.1111/j.1744-313X.2009.00848.x |

| [30] |

Ferrer CP, Vial CPA, Ferrés GM, et al. Genetic susceptibility to Andes Hantavirus:association between severity of disease and HLA alíeles in Chilean patients[J]. Rev Chilena Infectol, 2007, 24(5): 351-359. DOI:10.4067/S0716-10182007000500001 |

| [31] |

Kanerva M, Vaheri A, Mustonen J, et al. High-producer allele of tumour necrosis factor-alpha is part of the susceptibility MHC haplotype in severe puumala virus-induced nephropathia epidemica[J]. Scand J Infect Dis, 1998, 30(5): 532-534. DOI:10.1080/00365549850161629 |

| [32] |

Maes P, Clement J, Groeneveld PHP, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-α genetic predisposing factors can influence clinical severity in nephropathia epidemica[J]. Viral Immunol, 2006, 19(3): 558-564. DOI:10.1089/vim.2006.19.558 |

| [33] |

Liu ZW, Gao MC, Han QY, et al. Platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa (HPA-1 and HPA-3) polymorphisms in patients with hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome[J]. Hum Immunol, 2009, 70(6): 452-456. DOI:10.1016/j.humimm.2009.03.009 |

| [34] |

Muçaj S, Kabashi S, Ahmeti S, et al. Collective immunity of the population from endemic zones of hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome in Kosovo[J]. Med Arch, 2009, 63(3): 160-162. |

| [35] |

Hansen A, Cameron S, Liu QY, et al. Transmission of haemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome in china and the role of climate factors:a review[J]. Int J Infect Dis, 2015, 33: 212-218. DOI:10.1016/j.ijid.2015.02.010 |

| [36] |

Gracia JR, Schumann B, Seidler A. Climate variability and the occurrence of human puumala hantavirus infections in Europe:a systematic review[J]. Zoonoses Public Hlth, 2015, 62(6): 465-478. DOI:10.1111/zph.12175 |

| [37] |

Çelebi G, Öztoprak N, Öktem İMA, et al. Dynamics of Puumala hantavirus outbreak in Black Sea Region, Turkey[J]. Zoon Public Health, 2019, 66(7): 783-797. DOI:10.1111/zph.12625 |

| [38] |

Bai YT, Xu ZG, Lu B, et al. Effects of climate and rodent factors on hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome in Chongqing, China, 1997-2008[J]. PLoS One, 2015, 10(7): e0133218. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0133218 |

| [39] |

Engelthaler DM, Mosley DG, Cheek JE, et al. Climatic and environmental patterns associated with hantavirus pulmonary syndrome, four corners region, United States[J]. Emerg Infect Dis, 1999, 5(1): 87-94. DOI:10.3201/eid0501.990110 |

| [40] |

Tersago K, Verhagen R, Servais A, et al. Hantavirus disease (nephropathia epidemica) in Belgium:effects of tree seed production and climate[J]. Epidemiol Infect, 2009, 137(2): 250-256. DOI:10.2307/25476898 |

| [41] |

Clement J, Vercauteren J, Verstraeten WW, et al. Relating increasing hantavirus incidences to the changing climate:the mast connection[J]. Int J Health Geogr, 2009, 8(1): 1. DOI:10.1186/1476-072X-8-1 |

| [42] |

Li CP, Cui Z, Li SL, et al. Association between hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome epidemic and climate factors in Heilongjiang province, China[J]. Am J Trop Med Hyg, 2013, 89(5): 1006-1012. DOI:10.4269/ajtmh.12-0473 |

| [43] |

Tian HY, Yu PB, Luis AD, et al. Changes in rodent abundance and weather conditions potentially drive hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome outbreaks in Xi'an, China, 2005-2012[J]. PLoS Negl Trop Dis, 2015, 9(3): e0003530. DOI:10.1371/journal.pntd.0003530 |

| [44] |

Zhang WY, Fang LQ, Jiang JF, et al. Predicting the risk of hantavirus infection in Beijing, People's Republic of China[J]. Am J Trop Med Hyg, 2009, 80(4): 678-683. DOI:10.4269/ajtmh.2009.80.678 |

| [45] |

Liu J, Xue FZ, Wang JZ, et al. Association of haemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome and weather factors in Junan County, China:a case-crossover study[J]. Epidemiol Infect, 2013, 141(4): 697-705. DOI:10.1017/S0950268812001434 |

| [46] |

Aars J, Ims RA. Intrinsic and climatic determinants of population demography:the winter dynamics of tundra voles[J]. Ecology, 2002, 83(12): 3449-3456. DOI:10.1890/0012-9658(2002)083[3449:IACDOP]2.0.CO;2 |

| [47] |

Lin HL, Zhang ZT, Lu L, et al. Meteorological factors are associated with hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome in Jiaonan County, China, 2006-2011[J]. Int J Biometeorol, 2014, 58(6): 1031-1037. DOI:10.1007/s00484-013-0688-1 |

| [48] |

Xiao H, Lin XL, Gao LD, et al. Ecology and geography of hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome in Changsha, China[J]. BMC Infect Dis, 2013, 13(1): 305. DOI:10.1186/1471-2334-13-305 |

| [49] |

Jiang FC, Wang L, Wang S, et al. Meteorological factors affect the epidemiology of hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome via altering the breeding and hantavirus-carrying states of rodents and mites:a 9 years' longitudinal study[J]. Emerg Microbes Infect, 2017, 6(1): 1-9. DOI:10.1038/emi.2017.92 |

| [50] |

Xiao H, Tian HY, Cazelles B, et al. Atmospheric moisture variability and transmission of hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome in Changsha City, Mainland China, 1991-2010[J]. PLoS Negl Trop Dis, 2013, 7(6): e2260. DOI:10.1371/journal.pntd.0002260 |

| [51] |

Wei L, Qian Q, Wang ZQ, et al. Using geographic information system-based ecologic niche models to forecast the risk of hantavirus infection in Shandong Province, China[J]. Am J Trop Med Hyg, 2011, 84(3): 497-503. DOI:10.4269/ajtmh.2011.10-0314 |

| [52] |

Luis AD, Douglass RJ, Mills JN, et al. The effect of seasonality, density and climate on the population dynamics of Montana deer mice, important reservoir hosts for Sin Nombre hantavirus[J]. J Anim Ecol, 2010, 79(2): 462-470. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2656.2009.01646.x |

| [53] |

Zhang WY, Guo WD, Fang LQ, et al. Climate variability and hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome transmission in northeastern China[J]. Environ Health Persp, 2010, 118(7): 915-920. DOI:10.1289/ehp.0901504 |

| [54] |

Bi P, Wu XK, Zhang FZ, et al. Seasonal rainfall variability, the incidence of hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome, and prediction of the disease in low-lying areas of China[J]. Am J Epidemiol, 1998, 148(3): 276-281. DOI:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009636 |

| [55] |

陈化新, 李全乐. 中国历次洪涝灾害对肾综合征出血热流行的影响[J]. 中国公共卫生, 1999, 15(7): 666-667. Chen HX, Li QL. The effect of hemorrhagic fever with renal caused by flood and waterlogging in China[J]. Chin J Public Health, 1999, 15(7): 666-667. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:1001-0580.1999.07.052 |

| [56] |

王玉林, 李大年, 郑锐, 等. 安庆市洪涝灾区鼠密度及鼠带肾综合征出血热病毒率调查分析[J]. 中国媒介生物学及控制杂志, 1999, 10(5): 380-382. Wang YL, Li DN, Zheng R, et al. Investigation and analysis of rat density and rat hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome virus rate in flood-affected areas of Anqing City[J]. Chin J Vector Biol Control, 1999, 10(5): 380-382. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1003-4692.1999.05.020 |

| [57] |

Wolfe ND, Daszak P, Kilpatrick AM, et al. Bushmeat hunting, deforestation, and prediction of zoonotic disease[J]. Emerg Infect Dis, 2005, 11(12): 1822-1827. DOI:10.3201/eid1112.040789 |

| [58] |

Olsson GE, Hjertqvist M, Lundkvist Å, et al. Predicting high risk for human hantavirus infections, Sweden[J]. Emerg Infect Dis, 2009, 15(1): 104-106. DOI:10.3201/eid1501.080502 |

| [59] |

Kremen C, Niles JO, Dalton MG, et al. Economic incentives for rain forest conservation across scales[J]. Science, 2000, 288(5472): 1828-1832. DOI:10.1126/science.288.5472.1828 |

| [60] |

Hughes JB, Daily GC, Ehrlich PR. Population diversity:its extent and extinction[J]. Science, 1997, 278(5338): 689-692. DOI:10.1126/science.278.5338.689 |

| [61] |

Clay CA, Lehmer EM, Jeor SS, et al. Testing mechanisms of the dilution effect:deer mice encounter rates, sin nombre virus prevalence and species diversity[J]. Ecohealth, 2009, 6(2): 250-259. DOI:10.1007/s10393-009-0240-2 |

| [62] |

Tersago K, Schreurs A, Linard C, et al. Population, environmental, and community effects on local bank vole (Myodes glareolus) Puumala virus infection in an area with low human incidence[J]. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis, 2008, 8(2): 235-244. DOI:10.1089/vbz.2007.0160 |

| [63] |

Dizney LJ, Ruedas LA. Increased host species diversity and decreased prevalence of sin nombre virus[J]. Emerg Infect Dis, 2009, 15(7): 1012-1018. DOI:10.3201/eid1507.081083 |

| [64] |

Bowers MA, Dooley JL Jr. A controlled, hierarchical study of habitat fragmentation:responses at the individual, patch, and landscape scale[J]. Landscape Ecol, 1999, 14(4): 381-389. DOI:10.1023/a:1008014426117 |

| [65] |

Andreassen HP, Ims RA, Steinset IOK. Discontinuous habitat corridors:effects on male root vole movements[J]. J Appl Ecol, 1996, 33(3): 555-560. DOI:10.2307/2404984 |

| [66] |

Lehmer EM, Clay CA, Pearce-Duvet J, et al. Differential regulation of pathogens:the role of habitat disturbance in predicting prevalence of sin nombre virus[J]. Oecologia, 2008, 155(3): 429-439. DOI:10.1007/s00442-007-0922-9 |

| [67] |

Asner GP, Elmore AJ, Olander LP, et al. Grazing systems, ecosystem responses, and global change[J]. Annu Rev Env Resour, 2004, 29: 261-299. DOI:10.1146/annurev.energy.29.062403.102142 |

| [68] |

Suzán G, Armién A, Mills JN, et al. Epidemiological considerations of rodent community composition in fragmented landscapes in Panama[J]. J Mammal, 2008, 89(3): 684-690. DOI:10.1644/07-MAMM-A-015R1.1 |

| [69] |

Yan L, Liu W, Huang HG, et al. Landscape elements and Hantaan virus-related hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome, People's Republic of China[J]. Emerg Infect Dis, 2007, 13(9): 1301-1306. DOI:10.3201/eid1309.061481 |

| [70] |

Zhang YZ, Dong X, Li X, et al. Seoul virus and hantavirus disease, Shenyang, People's Republic of China[J]. Emerg Infect Dis, 2009, 15(2): 200-206. DOI:10.3201/eid1502.080291 |

| [71] |

Goodin DG, Koch DE, Owen RD, et al. Land cover associated with hantavirus presence in Paraguay[J]. Global Ecol Biogeogr, 2006, 15(5): 519-527. DOI:10.1111/j.1466-822X.2006.00244.x |

| [72] |

Previtali MA, Lehmer EM, Pearce-Duvet JMC, et al. Roles of human disturbance, precipitation, and a pathogen on the survival and reproductive probabilities of deer mice[J]. Ecology, 2010, 91(2): 582-592. DOI:10.1890/08-2308.1 |

| [73] |

Prist PR, Uriarte M, Fernandes K, et al. Climate change and sugarcane expansion increase Hantavirus infection risk[J]. PLoS Negl Trop Dis, 2017, 11(7): e0005705. DOI:10.1371/journal.pntd.0005705 |

| [74] |

Maurice AD, Ervin E, Schumacher M, et al. Exposure characteristics of hantavirus pulmonary syndrome patients, united states, 1993-2015[J]. Emerg Infect Dis, 2017, 23(5): 733-739. DOI:10.3201/eid2305.161770 |

| [75] |

Heyman P, Vaheri A, Lundkvist Å, et al. Hantavirus infections in Europe:from virus carriers to a major public-health problem[J]. Expert Rev Anti-Infect Ther, 2009, 7(2): 205-217. DOI:10.1586/14787210.7.2.205 |

| [76] |

Schmaljohn C, Hjelle B. Hantaviruses:a global disease problem[J]. Emerg Infect Dis, 1997, 3(2): 95-104. DOI:10.3201/eid0302.970202 |

| [77] |

Vapalahti K, Virtala AM, Vaheri A, et al. Case-control study on Puumala virus infection:smoking is a risk factor[J]. Epidemiol Infect, 2009, 138(4): 576-584. DOI:10.1017/S095026880999077X |

| [78] |

Tian HY, Hu SX, Cazelles B, et al. Urbanization prolongs hantavirus epidemics in cities[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2018, 115(18): 4707-4712. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1712767115 |

| [79] |

Prist PR, Uriarte M, Tambosi LR, et al. Landscape, environmental and social predictors of hantavirus risk in São Paulo, Brazil[J]. PLoS One, 2016, 11(10): e0163459. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0163459 |

| [80] |

Zhang S, Wang SQ, Yin WW, et al. Epidemic characteristics of hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome in China, 2006-2012[J]. BMC Infect Dis, 2014, 14(1): 384. DOI:10.1186/1471-2334-14-384 |

2020, Vol. 41

2020, Vol. 41