文章信息

- 王晓君, 李月华, 易凤莲, 付谦.

- Wang Xiaojun, Li Yuehua, Yi Fenglian, Fu Qian

- 1990-2017年中国结核病流行与控制情况

- Description of epidemic features and control status on tuberculosis in China, 1990-2017

- 中华流行病学杂志, 2020, 41(6): 856-860

- Chinese Journal of Epidemiology, 2020, 41(6): 856-860

- http://dx.doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn112338-20190809-00587

-

文章历史

收稿日期: 2019-08-09

2. 华中科技大学同济医学院医药卫生管理学院, 武汉 430030

2. School of Medicine and Health Management, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan 430030, China

自20世纪90年代以来,全国开始实施WHO推荐的现代结核病控制策略(DOTS),并采取一系列重大举措,包括开展全国流行病学调查,制定结核病防治规划,实施结核病控制项目等,使得我国提前5年实现联合国2015年千年发展目标确定的结核病控制指标[1-3],为全球结核病的防控做出了巨大的贡献。近年来,随着耐药结核病、结核杆菌/艾滋病病毒(TB/HIV)双重感染及流动人口的增加,全球结核病下降缓慢,我国仍然是全球结核病高负担国家之一[4-5],特别是在“健康中国2030”及2035年终止结核目标的大背景下,我国结核病的防控任务艰巨。本研究利用2017年全球疾病负担研究(Global Burden of Disease Study,GBD2017)数据,分析我国1990-2017年结核病的发病及死亡的变化趋势及特点,为我国制定结核病防治策略及实现2035年终止结核目标提供科学依据。

资料与方法1.资料来源:来源于华盛顿大学健康计量与评估研究中心(Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation,IHME)GBD2017年数据。GBD是一项系统的科学工作,对全球195个国家和地区的354种疾病和伤害的数据,采用统一方法进行建模、校正,并做出准确和全面的估算,目的是使其结果随时间、跨年龄组和人群进行比较[6]。本研究收集的是GBD2017我国1990-2017年结核病的发病及死亡数据,其数据主要来源于中国疾病预防控制系统疾病监测系统、全国法定报告传染病监测系统、全国结核病流行病学抽样调查数据、《中国卫生统计年鉴》以及已发表的文献和报告等。

2.研究内容:中国2017年不同年龄、性别、耐药类型结核病的发病及死亡情况;中国1990-2017年结核病发病及死亡的变化趋势及不同耐药类型结核病的发病及死亡的变化趋势。

GBD2017根据结核病的耐药类型[7],分为药物敏感结核病(drug-sensitive TB,STB)、耐多药结核病(multidrug-resistant tuberculosis,MDRTB)及广泛耐药结核病(extensively drug-resistant,XDRTB);其中MDRTB指结核病患者感染的结核分枝杆菌经体外药敏试验证实至少同时对异烟肼和利福平(抗结核一线药物)耐药;而XDRTB指除对异烟肼和利福平耐药外,至少同时对任意一种氟喹诺酮类药物和对任意一种二线抗结核药物注射剂(卷曲霉素、卡那霉素、阿米卡星)耐药。

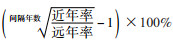

3.统计学分析:本研究利用GBD2017对中国结核病数据进行描述性分析,主要指标包括,发病数(年龄标化发病率)、死亡数(年龄标化死亡率)、年均递降率或递增率(R)。GBD2017以世界标准人口计算年龄标准化率[8]。R的计算公式为:R=

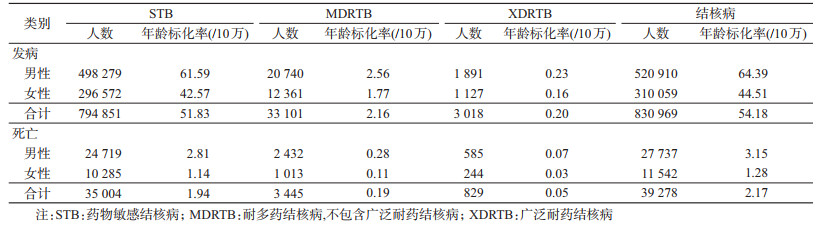

1. 2017年结核病发病及死亡情况:2017年我国结核病发病数约有83.10万,年龄标化发病率为54.18/10万;男性(52.09万)的发病数是女性(31.01万)的1.68倍(表 1);不同年龄组人群中,20~30岁及45~65岁人群的发病数最多,≥65岁人群随着年龄增长,发病数逐渐下降(图 1)。2017年我国约有3.93万人因结核病死亡,年龄标化死亡率为2.17/10万;男性(2.77万)的死亡数是女性(1.15万)的2.41倍(表 1);不同年龄组人群中,60~80岁人群的死亡数最多(图 1)。

|

| 图 1 2017年中国结核病不同年龄组人群的发病数及死亡数 |

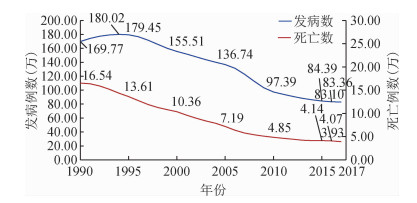

2. 2017年不同耐药类型结核病的发病及死亡情况:2017年我国STB、MDRTB、XDRTB的发病数(年龄标化发病率)分别是79.48万(51.83/10万)、3.31万(2.16/10万)和0.30万(0.20/10万);死亡数(年龄标化死亡率)分别是3.50万(1.94/10万)、0.34万(0.19/10万)和0.08万(0.05/10万);死亡数分别占发病数的4.40%、10.27%和26.67%。男性不同耐药类型结核病的发病数及死亡数均多于女性(表 1)。

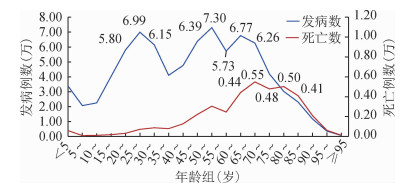

3. 1990-2017年结核病的发病及死亡变化趋势:我国结核病的发病数从1990年的169.77万,下降到2017年的83.10万,下降了51.05%,年均递降率为2.61%(年龄标化发病率的年均递降率为3.61%);我国结核病的发病数从1990-1994年有上升的趋势,从1995年开始逐年下降,年均递降3.31%;其中,2005-2010年下降速率最快,年均递降6.56%;2010-2017年下降缓慢,年均递降2.24%,2017年(83.10万)较2016年(83.36万)仅下降0.31%。结核病死亡数从1990年的16.54万下降到2017年的3.93万,下降了76.24%,年均递降率为5.18%(年龄标化死亡率的年均递降率为7.54%),2017年(3.93万)较2016年(4.07万)仅下降3.44%(图 2)。

|

| 图 2 1990-2017年中国结核病的发病数及死亡数 |

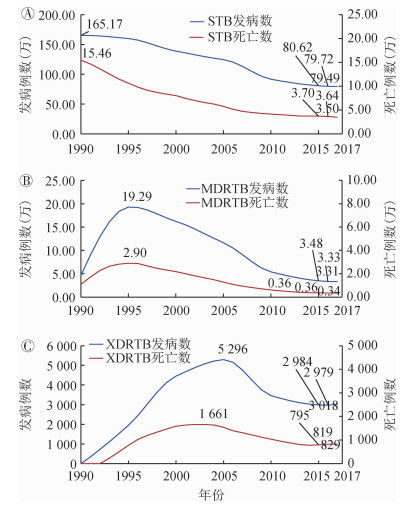

4. 1990-2017年不同耐药类型结核病的发病及死亡的变化趋势:1990-2017年STB的发病数和死亡数均呈现逐年下降的趋势(图 3A),1990年的发病数及死亡数最高,分别为165.17万、15.46万,年均递降率分别为2.67%、5.35%。MDRTB的发病数及死亡数呈现先升后降的趋势(图 3B),且均是1995年最高,分别为19.29万、2.90万;1995年之后逐年下降,年均递降率分别为7.70%、9.28%。XDRTB的发病数和死亡数也呈现先升后降的趋势(图 3C),发病数最高的是2005年的5 296例,之后呈下降趋势,年均递降率为4.63%;死亡数最高的是2003年的1 661例,之后呈下降趋势,年均递降率为5.24%;但2017年的发病数(3 018例)较2016年(2 979例)增长了1.32%,2017年的死亡数(829例)较2016年(819例)增长了1.22%。

|

| 注:STB:药物敏感结核病;MDRTB:耐多药结核病,不包含广泛耐药结核病;XDRTB:广泛耐药结核病 图 3 1990-2017年中国不同耐药类型结核病的发病数和死亡数 |

本研究利用GBD2017中国结核病的数据分析了我国结核病的发病及死亡的特征以及其变化趋势。结果显示,2017年我国结核病的发病数及死亡数分别是83.10万(54.18/10万)、3.93万(2.17/10万);其中,男性发病数和死亡数均高于女性,发病数较高的主要是<65岁人群(20~30岁及45~65岁),这与以往研究结果一致[4, 9];我国结核病死亡数最多的是老年人群(60~80岁),而全球结核病死亡数较多的主要是<65岁人群[4],这是否与我国人口老龄化、老年结核病患者涂阳患病率高以及老年患者就诊延迟的比例逐年增长而导致其死亡数增多有关[10-11],还需要进一步的研究。

本研究结果显示,我国结核病的发病数在1994年前呈上升趋势,1995年之后开始逐年下降。从结核病的耐药类型来分析我国1995年前结核病疫情上升的特点,其中STB呈逐年下降趋势,其主要原因是由于MDRTB的发病数急剧增多,1995年高达19.29万,XDRTB虽呈上升趋势,但是其发病数不到0.20万(图 3);另一方面,我国自《结核病防治规划》(1978年)、《传染病防治法》(1989年)及《结核病防治管理办法》(1991年)发布初期,就开始要求建立结核病疫情登记、报告制度,明确规定了各级医疗机构的职责,特别是DOTS策略的实施,促进了结核病患者的发现,使得结核病发病数增加[12]。

1990-2017年,我国结核病的疫情总体呈下降趋势,发病数和死亡数的年均递减率分别为2.61%和5.18%,发病率和死亡率的年均递降率分别为3.61%和7.54%。尽管我国发病率和死亡率的年均递降率高于全球(2%和3%),但低于欧洲及非洲等地区;同时与WHO终止结核策略2020年的阶段性目标的发病率年均递降率4.4%和死亡数年均递降率8.0%相比[5],还存在一定的差距。研究表明,加大患者发现,减少潜伏感染者发展成为活动性肺结核,以及增加结核病的治疗成功率是结核病疫情控制的主要因素[13]。20世纪90年代WHO的DOTS策略仅覆盖我国的一半地区,2000年以后国家加大DOTS策略的推行,到2005年覆盖了全国,一方面使得标准化短程治疗方案在全国实施,另一方面使得免费治疗政策惠及到所有活动性肺结核患者,新患者的发现也从30%增加到80%[1]。2003年继呼吸道传染病严重急性呼吸道综合征(SARS)疫情控制之后,政府加强了对公共卫生系统的领导,增加了资金投入,修订了传染病控制的相关法律,实施了互联网疾病报告系统等措施,为结核病的控制提供了保障[14]。2010年全国第五次结核病流行病学抽样调查结果显示,结核病的疫情较2000年有所下降[2]。本研究也发现,2005-2010年,我国结核病发病数下降速率较快,2010年后下降缓慢,近年来死亡数的下降速率也减缓。WHO 2019年结核病报告显示,我国新发结核病患者数居全球第2位[5];新报告结核病患者数也居我国甲乙类传染病第2位,为此我国制定了《遏制结核病行动计划(2019-2022年)》,明确了我国近期结核病的控制的目标和方向[15]。

GBD2017数据结果显示,全球MDRTB和XDRTB年龄标准化死亡率分别为1.6/10万、0.2/10万[7]。我国MDRTB(0.19/10万)和XDRTB(0.05/10万)的年龄标准化死亡率虽然低于全球;但值得注意的是,我国耐多药/利福平耐药的发病数居全球第2(占全球13%)[5];2017年我国MDRTB和XDRTB死亡数分别占发病数10.27%及26.67%,远高于STB死亡数在发病数中的占比(4.40%),其死亡数近年来也下降缓慢,甚至XDRTB的发病数及死亡数较2016年有所增长。研究显示,我国培养阳性的结核病患者中,XDRTB患者约占10%[16-17]。同时,由于近年来MDRTB和XDRTB原发耐药比例增多,相对于STB患者的治疗成功率低,生存时间短等[18-20],给我国结核病的控制乃至终止带来了巨大挑战。

此外,考虑到我国人口基数大、潜伏感染者多、地区发展不均衡、人口老龄化、流动人口增加、耐药患者纳入治疗率低、经济负担重等诸多困难,我国仍是结核病高负担国家之一,我国必须在现有的基础上加大结核病患者发现、诊治的力度,优化结核病防治服务体系,增加经费投入,以保障我国如期实现WHO 2035年终止结核目标。

综上所述,1990-2017年我国结核病疫情总体呈下降趋势,但近年来下降速率缓慢,其中XDRTB的增加应引起重视。

利益冲突 所有作者均声明不存在利益冲突

| [1] |

Wang LX, Zhang H, Ruan YZ, et al. Tuberculosis prevalence in China, 1990-2010:a longitudinal analysis of national survey data[J]. Lancet, 2014, 383(9934): 2057-2064. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62639-2 |

| [2] |

全国第五次结核病流行病学抽样调查技术指导组, 全国第五次结核病流行病学抽样调查办公室. 2010年全国第五次结核病流行病学抽样调查报告[J].中国防痨杂志, 2012, 34(8): 485-508. Technical Guidance Group of the Fifth National Tuberculosis Epidemiological Sampling Survey Office of the Fifth National Tuberculosis Epidemiological Sampling Survey. The fifth national tuberculosis epidemiological sampling survey in 2010[J]. Chin J Antituberc, 2012, 34(8): 485-508. |

| [3] |

国务院办公厅.国务院办公厅关于印发"十三五"全国结核病防治规划的通知[EB/OL]. (2017-02-16)[2019-07-01]. http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2017-02/16/content_5168491.htm. General Office of the State Council of the People's Republic of China. Notice of the general office of the state council of the people's republic of China on printing and distributing the national thirteen-five plan for tuberculosis prevention and control[EB/OL]. (2017-02-16)[2019-07-01]. http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2017-02/16/content_5168491.htm. |

| [4] |

Kyu HH, Maddison ER, Henry NJ, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of tuberculosis, 1990-2016:results from the Global burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors 2016 study[J]. Lancet Infect Dis, 2018, 18(12): 1329-1349. DOI:10.1016/s1473-3099(18)30625-x |

| [5] |

WHO. Global tuberculosis report 2019[EB/OL]. (2018-09-18)[2019-07-01]. https://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en/.

|

| [6] |

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. GBD protocol[EB/OL]. (2018-02-26)[2019-08-20]. http://www.healthdata.org/gbd/about/protocol.

|

| [7] |

GBD 2017 Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality for 282 causes of death in 195 countries and territories, 1980-2017:a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017[J]. Lancet, 2018, 392(10159): 1736-1788. DOI:10.1016/s0140-6736(18)32203-7 |

| [8] |

Dicker D, Nguyen G, Abate D, et al. Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality and life expectancy, 1950-2017:a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017[J]. Lancet, 2018, 392(10159): 1684-1735. DOI:10.1016/s0140-6736(18)31891-9 |

| [9] |

Zhu S, Xia L, Yu SC, et al. The burden and challenges of tuberculosis in China:findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015[J]. Sci Rep, 2017, 7: 14601. DOI:10.1038/s41598-017-15024-1 |

| [10] |

成诗明, 刘二勇, 杜昕. 老年结核病患者对中国结核病控制的影响[J]. 中华流行病学杂志, 2004, 25(8): 655-657. Cheng SM, Liu EY, Du X. The impact of geriatric tuberculosis patients on the tuberculosis control strategy in China[J]. Chin J Epidemiol, 2004, 25(8): 655-657. DOI:10.3760/j.issn:0254-6450.2004.08.004 |

| [11] |

王晓君, 付谦, 张正斌, 等. 武汉市2008-2017年结核病患者就诊延迟情况及影响因素分析[J]. 中华流行病学杂志, 2019, 40(6): 643-647. Wang XJ, Fu Q, Zhang ZB, et al. Delay on care-seeking and related influencing factors among tuberculosis patients in Wuhan, 2008-2017[J]. Chin J Epidemiol, 2019, 40(6): 643-647. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2019.06.008 |

| [12] |

刘剑君, 么鸿雁, 姜世闻, 等. 中国结核病患者的发现与现代结核病控制策略扩展关系的预测分析[J]. 中华流行病学杂志, 2004, 25(8): 647-649. Liu JJ, Yao HY, Jiang SW, et al. Analysis on the relationship between tuberculosis case detection and short-course coverage of directly observed treatment in China[J]. Chin J Epidemiol, 2004, 25(8): 647-649. DOI:10.3760/j.issn:0254-6450.2004.08.002 |

| [13] |

Xu KJ, Ding C, Mangan CJ, et al. Tuberculosis in China:A longitudinal predictive model of the general population and recommendations for achieving WHO goals[J]. Respirology, 2017, 22(7): 1423-1429. DOI:10.1111/resp.13078 |

| [14] |

Wang LD, Liu JJ, Chin DP. Progress in tuberculosis control and the evolving public-health system in China[J]. Lancet, 2007, 369(9562): 691-696. DOI:10.1016/s0140-6736(07)60316-x |

| [15] |

国家卫生健康委员会疾病预防控制局.关于印发《遏制结核病行动计划(2019-2022年)》的通知[EB/OL]. (2019-06-13)[2019-08-20]. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/jkj/s3589/201906/b30ae2842c5e4c9ea2f9d5557ad4b95f.shtml. Disease Prevention and Control Bureau, National Health Commition. Notice on the issuance of the Stop TB Action Plan (2019-2022)[EB/OL]. (2019-06-13)[2019-08-20]. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/jkj/s3589/201906/b30ae2842c5e4c9ea2f9d5557ad4b95f.shtml. |

| [16] |

Tang SJ, Zhang Q, Yu JM, et al. Extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis at a tuberculosis specialist hospital in Shanghai, China:clinical characteristics and treatment outcomes[J]. Scand J Infect Dis, 2011, 43(4): 280-285. DOI:10.3109/00365548.2010.548080 |

| [17] |

Tang SJ, Tan SY, Yao L, et al. Risk factors for poor treatment outcomes in patients with MDR-TB and XDR-TB in China:retrospective multi-center investigation[J]. PLoS One, 2013, 8(12): e82943. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0082943 |

| [18] |

Bei CL, Fu MJ, Zhang Y, et al. Mortality and associated factors of patients with extensive drug-resistant tuberculosis:an emerging public health crisis in China[J]. BMC Infect Dis, 2018, 18: 261. DOI:10.1186/s12879-018-3169-7 |

| [19] |

Liu CH, Li L, Chen Z, et al. Characteristics and treatment outcomes of patients with MDR and XDR tuberculosis in a TB referral hospital in Beijing:a 13-year experience[J]. PLoS One, 2011, 6(4): e19399. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0019399 |

| [20] |

Hu Y, Mathema B, Zhao Q, et al. Acquisition of second-line drug resistance and extensive drug resistance during recent transmission of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in rural China[J]. Clin Microbiol Infect, 2015, 21(12): 1093.e9-1093.e18. DOI:10.1016/j.cmi.2015.08.023 |

2020, Vol. 41

2020, Vol. 41