文章信息

- 尹浩, 马烨, 杨萱, 赵好, 韩孟杰.

- Yin Hao, Ma Ye, Yang Xuan, Zhao Hao, Han Mengjie

- 我国14岁及以下HIV感染儿童生存分析

- Survival analysis on HIV-infected children aged 14 years old and younger in China

- 中华流行病学杂志, 2020, 41(6): 850-855

- Chinese Journal of Epidemiology, 2020, 41(6): 850-855

- http://dx.doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn112338-20191129-00844

-

文章历史

收稿日期: 2019-11-29

随着treatment as prevention(TasP)概念的提出,使得抗病毒治疗在预防艾滋病传播方面成为优先选择的方案。因此,为了有效控制艾滋病的危害与传播,达到终止艾滋病流行的目的,艾滋病联合规划署(UNAIDS)提出了“90-90-90”目标,即2020年,90%的HIV感染者知晓自身感染状态,90%的HIV确诊者获得持续的抗病毒治疗,90%的抗病毒治疗者体内病毒得到抑制[1]。

截至2017年底,全球共有3 690万人感染HIV,其中≤14岁感染儿童180万人,占全部HIV感染者的4.88%[2]。HIV感染儿童由于年龄小,生理功能尚未成熟且自我管理能力较低,疾病进展较快,需要及时进行治疗[3]。现阶段国内外针对HIV感染儿童全阶段生存情况及影响因素的研究较少,因此本研究将通过回顾性研究对我国≤14岁HIV感染儿童生存情况及影响因素进行探究。

对象与方法1.研究对象:来源于我国艾滋病综合防治基本信息系统病例报告及抗病毒治疗数据库,收集截至2018年12月31日,年龄≤14岁且通过母婴传播感染HIV的儿童相关数据。剔除标准:①出生日期信息缺失;②户籍信息缺失;③确诊阳性日期缺失。共剔除185例。所有HIV感染儿童信息都由其监护人签署知情同意书,允许其数据用于本研究。

2.研究方法:采取回顾性队列研究方法,对母婴传播途径感染HIV的儿童生存情况进行观察,以出生日期为观察起点,2018年12月31日为观察终点。选取观察儿童原始卡片信息作为基线数据,收集调查儿童年龄、性别、民族、确诊阳性年龄、治疗类型、是否获得关怀服务等信息。

3.相关定义:①生存时间:从出生日期至出现死亡之间的时间跨度,以月为单位。②删失:截至观察终点仍然存活但在观察期内失访,定义为结尾删失;删失个体生存时间为观察起点与删失日期或观察终点之间的时间间隔。③HIV感染年代:根据感染HIV年份(出生日期)来划分感染年,2011年1月1日以前感染的儿童为一组,2011年1月1日至2015年12月31日感染HIV的儿童为一组,2016年以后感染HIV的儿童为一组。④所属地区:以儿童现住址信息为依据,地理分布分为东北、华北、华中、华东、华南、西北和西南地区。⑤治疗类型:数据库内现住址与治疗机构在同一城市者为本地治疗,否则为异地治疗。⑥接受抗病毒治疗:持续治疗时间≥180 d的儿童。⑦获得关怀服务:指从确诊阳性日期起的365 d内接受了CD4+T淋巴细胞计数(CD4)检测。

4.统计学分析:采用SAS 9.4软件整理和分析数据。连续变量采用中位数及四分位数间距方式表示,分类变量采用频数和构成比方式表示。采用寿命表法对生存曲线进行估计,采用单因素和多因素Cox比例风险回归模型对影响生存时间的因素进行筛选。多因素逐步回归分析,自变量的纳入标准为0.05,剔除标准为0.10。双侧检验,检验水准α=0.05。

结 果1. HIV感染儿童:

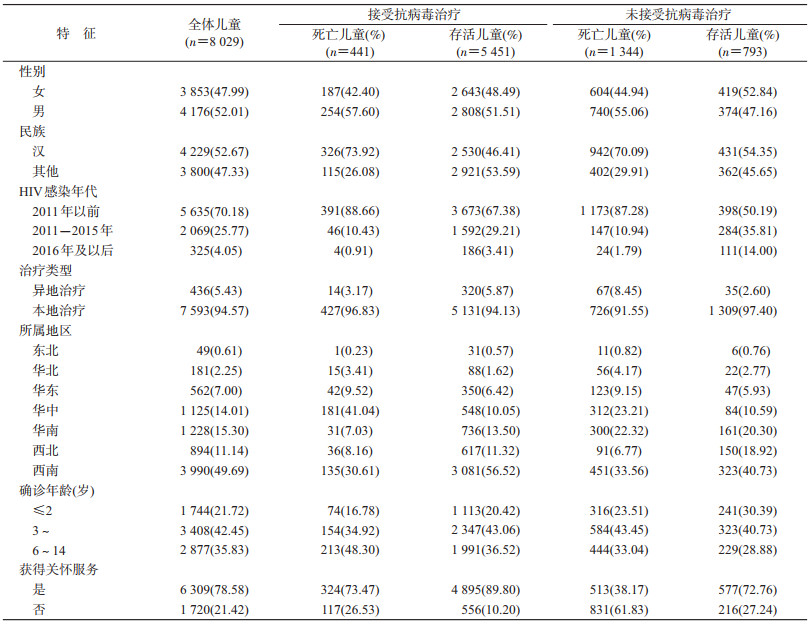

(1)基本情况:HIV感染儿童8 029例,其中5 892例(73.38%)接受抗病毒治疗。男性儿童4 176人(52.01%);汉族儿童4 229人(52.67%);2011年以前感染HIV的儿童5 635人(70.18%)。确诊阳性年龄中位数为3.85岁,四分位数间距为4.01岁;异地治疗儿童比例仅为5.43%;6 309例(78.58%)儿童获得关怀服务。地区分布方面,HIV感染儿童主要集中在西南地区,共计3 990例(49.69%)。见表 1。

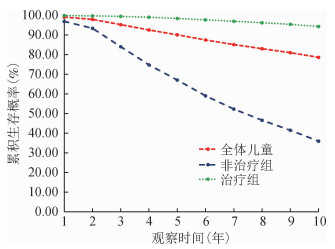

(2)生存情况:截至观察终点,8 029例儿童中,1 785例儿童死亡。中位生存时间179.75个月,观察对象确诊阳性后1、2、5、10年的累积生存概率分别为99.13%、97.95%、90.11%、78.63%。以是否接受抗病毒治疗分组,未接受抗病毒治疗组儿童中位生存时间89.13个月,1、2、5、10年的累积生存概率分别为96.95%、93.42%、67.09%、35.96%,接受抗病毒治疗组儿童中位生存时间179.98个月,1、2、5、10年的累积生存概率分别为99.92%、99.74%、98.44%、94.34%。两组中位生存时间差异有统计学意义(χ2=2 862.521 1,P<0.000 1)。见图 1。

|

| 图 1 我国≤14岁HIV感染儿童10年生存曲线 |

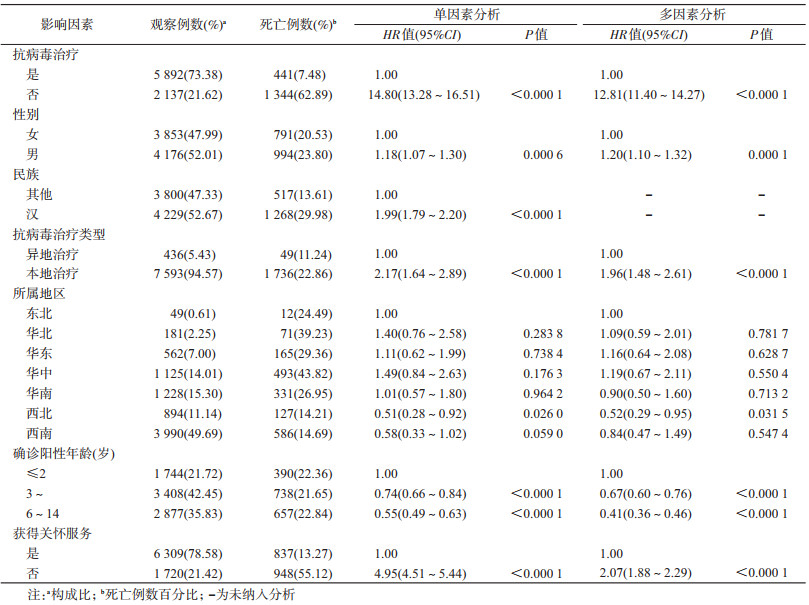

(3)生存时间的影响因素:①单因素分析:单因素Cox比例风险回归分析结果显示,性别、是否接受抗病毒治疗、治疗类型、确诊阳性年龄、儿童所属地区、是否获得关怀服务是HIV感染儿童生存时间可能的影响因素。见表 2。②多因素分析:将单因素分析有统计学意义的变量纳入多因素分析,建立关于生存时间的多因素Cox比例风险回归模型。结果显示,建立的生存时间回归模型差异有统计学意义(χ2=2 885.239 6,P<0.000 1)。比较HIV感染儿童死亡风险,发现未接受抗病毒治疗儿童的死亡风险是接受抗病毒治疗儿童的12.81倍(95%CI:11.40~14.27);确诊阳性年龄在3~5岁和6~14岁感染的儿童死亡风险分别是确诊阳性年龄≤2岁儿童的0.67倍(95%CI:0.60~0.76)和0.41倍(95%CI:0.36~0.46)。西北地区儿童的死亡风险是东北地区儿童的0.52倍(95%CI:0.29~0.95),本地治疗儿童的死亡风险是异地治疗儿童的1.96倍(95%CI:1.48~2.61);未获得关怀服务儿童死亡风险是获得关怀服务儿童的2.07倍(95%CI:1.88~2.29)。见表 2。

2.亚组儿童:

(1)未接受治疗死亡儿童:8 029例HIV感染儿童中,共计1 344例未接受抗病毒治疗儿童在观察期间发生死亡。男性740例(55.06%);汉族942例(70.09%);本地治疗1 309例(97.40%)。儿童人数最多的地区为西南地区,为451例(33.56%),确诊阳性年龄≥6岁儿童为444人(33.04%);513例(38.17%)儿童获得了关怀服务。

通过对未接受治疗的HIV感染儿童,建立生存时间的多因素Cox比例风险回归模型。结果显示,建立的生存时间回归模型有统计学意义(χ2=535.816 5,P<0.000 1)。比较死亡风险发现,男童死亡风险是女童的1.19倍(95%CI:1.07~1.33);确诊阳性年龄在3~5岁和6~14岁儿童的死亡风险分别是确诊阳性年龄≤2岁儿童的0.61倍(95%CI:0.53~0.70)和0.30倍(95%CI:0.26~0.35),未获得关怀服务儿童的死亡风险是获得关怀服务儿童的2.17倍(95%CI:1.94~2.43)。

(2)接受治疗死亡儿童:441例接受抗病毒治疗儿童死亡,其中男性儿童254例(57.60%);汉族儿童326例(73.92%);213例(48.30%)儿童确诊阳性年龄≥6岁;本地治疗感染儿童427例(96.83%);获得关怀服务儿童324例(73.47%)。50.34%儿童在确诊阳性后3个月内启动治疗,40.59%在确诊阳性6个月后才启动抗病毒治疗。441例儿童中,有232人(52.61%)采用齐多夫定(AZT)+拉米夫定(3TC)+奈韦拉平(NVP)/依非韦伦(EFV)作为基线治疗方案。药物使用方面,治疗方案内包含最多的药物为拉米夫定(3TC),共399例儿童的治疗方案内包含此药。

讨 论截至观察终点,我国≤14岁HIV感染儿童平均生存时间为179.75个月,高于泰国南部地区和埃塞俄比亚北部地区同年龄组儿童生存时间[4-5]。观察对象确诊阳性后1、2、5、10年的累积生存概率均高于福建省同年龄组儿童研究结果[6]。儿童的免疫系统相较成年人更易受到病毒的影响,一旦HIV感染,病程进展迅速,在得不到很好的关怀治疗服务情况下,很快会发生死亡[7]。同时部分HIV感染儿童发现较晚,在诊断后病程迅速进展,从而在确诊阳性1年内死亡[8]。从分组情况来看,接受抗病毒治疗组儿童10年的累积生存概率高于我国河南省同年龄组[9],1、2、5、10年累计生存概率均高于坦桑尼亚、印度和埃塞俄比亚的HIV感染儿童[10-12]。

通过对HIV感染儿童确诊阳性年龄的分析发现,与确诊阳性低年龄组相比,确诊阳性高年龄组具有更低的死亡风险。HIV感染儿童病程进展迅速,大多数在未经确诊之前便死亡。确诊阳性高年龄组经历了早期死亡的筛选,较确诊阳性低年龄组具有更高的免疫水平,因此高年龄组死亡数更低。但对于具有HIV暴露风险的儿童而言,扩大HIV检测覆盖率的同时做到尽早确诊,有利于发现更多的HIV感染儿童,使更多HIV感染儿童在未死亡之前就接受HIV关怀治疗服务,有效控制病程进展,从而降低其死亡风险[13-14]。目前我国已经建立了以婴儿早期诊断(EID)区域实验室为中心、其他医疗卫生机构共同参与的婴儿早诊检测网络,新生儿检测比例逐年升高[15-16],死亡比例逐年下降。因此应进一步扩大儿童检测覆盖率,尽早了解具有HIV感染风险儿童的感染状态,以达到降低其死亡风险的目的。是否获得HIV相关关怀服务及关怀服务质量的好坏直接影响了HIV感染者生存质量及生存结局[17]。本研究中6 309例(78.58%)儿童获得了关怀服务,高于南非农村HIV感染儿童研究结果[18],但低于印度和非洲部分国家同年龄组儿童在2013年和2014年的研究结果[19-20]。

多项随机临床实验证实抗病毒治疗的引入在延长HIV感染者寿命的同时有效降低了感染人群的患病率和病死率[21-23]。HIV感染儿童确诊阳性后立即接受抗病毒治疗,可以有效地延缓艾滋病疾病进程以及相关死亡[24-26]。本研究生存分析结果显示接受和未接受抗病毒治疗两组儿童生存曲线之间差异有统计学意义,说明接受抗病毒治疗可以有效延长HIV感染儿童生存时间,显著降低艾滋病相关死亡风险,与其他研究结果相符合[12, 22, 27]。

对不同人口学特征进行比较发现,男性、本地治疗会增加HIV感染儿童的死亡风险。一般研究结果认为,异地就医感染者对当地治疗随访机构不配合,导致其管理难度增大,服药依从性较差,容易导致死亡[28-29],与本研究结果不同。通过对异地治疗儿童的研究发现,异地治疗儿童多是前往所在省或自治区的省会城市的儿童抗病毒治疗医院进行治疗;或是从经济欠发达地区前往经济较为发达地区的儿童抗病毒治疗医院就诊。因此,异地治疗儿童获得的关怀治疗服务质量较本地治疗儿童更好,死亡风险更低。

从地区分布方面来看,西北地区死亡风险较低。研究数据结果表明,西北地区HIV感染儿童抗病毒治疗覆盖率(73.04%)高于其他地区,说明近年来,西北地区HIV感染儿童抗病毒治疗工作有进展。同时,西北地区死亡感染儿童多集中在新疆,新疆的HIV感染儿童病毒学失败比例相对较高[30],提示应进一步加大新疆抗病毒治疗服务质量,从而进一步降低该地区HIV感染儿童死亡风险。

本研究有不足。回顾性队列研究数据,无法全面了解HIV感染儿童监护人详细情况、儿童抗病毒治疗依从性以及可能影响HIV感染儿童生存的其他因素。同时由于数据库内的儿童均是确诊时仍存活的个体,因此无法对未经确诊就死亡的儿童进行分析,从而导致低估了某些因素的影响。此外,由于观察起点定义不同,未对接受抗病毒治疗儿童的死亡风险影响因素进行进一步分析,会在之后的研究中进一步讨论。

综上所述,我国≤14岁HIV感染儿童中位生存时间179.75个月。接受抗病毒治疗、女童、异地治疗、西北地区、获得关怀服务和确诊时年龄较大是HIV感染儿童生存时间的保护因素。

利益冲突 所有作者均声明不存在利益冲突

| [1] |

UNAIDS. Ending AIDS: progress towards the 90-90-90 targets[EB/OL]. (2017-03-08)[2019-12-18]. https://idpc.net/publications/2017/08/ending-aids-progress-towards-the-90-90-90-targets.

|

| [2] |

UNAIDS. UNAIDS data 2018[EB/OL]. (2018-07-28)[2019-12-18].https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2018/unaids-data-2018.

|

| [3] |

Zhao Y, Li CM, Sun X, et al. Mortality and treatment outcomes of China's National Pediatric antiretroviral therapy program[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2013, 56(5): 735-744. DOI:10.1093/cid/cis941 |

| [4] |

Chaimay B, Woradet S, Chantutanon S, et al. Clinical risk factors on survival among HIV-infected children born to HIV-infected mothers[J]. J Med Assoc Thai, 2013, 96(11): 1434-1443. DOI:10.7448/IAS.15.6.18217 |

| [5] |

Arage G, Assefa M, Worku T, et al. Survival rate of HIV-infected children after initiation of the antiretroviral therapy and its predictors in Ethiopia:a facility-based retrospective cohort[J]. SAGE Open Med, 2019, 7: 2050312119838957. DOI:10.1177/2050312119838957 |

| [6] |

陈亮, 张明雅, 严延生. 福建省2003-2015年儿童HIV/AIDS病例生存时间分析[J]. 中国公共卫生, 2016, 32(12): 1605-1608. Chen L, Zhang MY, Yan YS. Survival of children with HIV/AIDS in Fujian province, 2003-2015[J]. Chin J Public Health, 2016, 32(12): 1605-1608. DOI:10.11847/zgggws2016-32-12-01 |

| [7] |

曾小良, 鲁鸿燕, 覃祺, 等. 22例接受抗病毒治疗艾滋病儿童死亡原因分析[J]. 应用预防医学, 2016, 22(4): 289-292, 296. Zeng XL, Lu HY, Qin Q, et al. Analysis of death causes among 22 HIV/AIDS children who received antiretroviral therapy treatment[J]. J Appl Prev Med, 2016, 22(4): 289-292, 296. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1673-758X.2016.04.001 |

| [8] |

Li M, Tang WM, Bu K, et al. Mortality among People Living with HIV and AIDS in China:implications for enhancing linkage[J]. Sci Rep, 2016, 6: 28005. DOI:10.1038/srep28005 |

| [9] |

孙定勇, 杨文杰, 马彦民, 等. 2003-2014年河南省14岁及以下艾滋病抗病毒治疗患者生存分析[J]. 中华预防医学杂志, 2015, 49(8): 700-704. Sun DY, Yang WJ, Ma YM, et al. Survival analysis of the AIDS patients under 14 years of age and receiving antiretroviral treatment in Henan province from 2003 to 2014[J]. Chin J Prev Med, 2015, 49(8): 700-704. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-9624.2015.08.007 |

| [10] |

Somi G, Majigo M, Manyahi J, et al. Pediatric HIV care and treatment services in Tanzania:implications for survival[J]. BMC Health Serv Res, 2017, 17(1): 540. DOI:10.1186/s12913-017-2492-9 |

| [11] |

Rajasekaran S, Jeyaseelan L, Ravichandran N, et al. Efficacy of antiretroviral therapy program in children in India:prognostic factors and survival analysis[J]. J Trop Pediatr, 2009, 55(4): 225-232. DOI:10.1093/tropej/fmm073 |

| [12] |

Melaku Z, Lulseged S, Wang CH, et al. Outcomes among HIV-infected children initiating HIV care and antiretroviral treatment in Ethiopia[J]. Trop Med Int Health, 2017, 22(4): 474-484. DOI:10.1111/tmi.12834 |

| [13] |

Delpierre C, Cuzin L, Lauwers-Cances V, et al. High-Risk groups for late diagnosis of HIV infection:a need for rethinking testing policy in the general population[J]. AIDS Patient Care STDS, 2006, 20(12): 838-847. DOI:10.1089/apc.2006.20.838 |

| [14] |

Shabangu P, Beke A, Manda S, et al. Predictors of survival among HIV-positive children on ART in Swaziland[J]. Afr J AIDS Res, 2017, 16(4): 335-343. DOI:10.2989/16085906.2017.1386219 |

| [15] |

苏敏, 乔亚萍, 姚均, 等. 中国2015年HIV暴露婴儿早期诊断检测情况分析[J]. 中国妇幼健康研究, 2017, 28(3): 223-225. Su M, Qiao YP, Yao J, et al. Early diagnosis and detection for HIV exposed infants in China in 2015[J]. Chin J Woman Chil Health Res, 2017, 28(3): 223-225. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1673-5293.2017.03.001 |

| [16] |

乔亚萍, 王潇滟, 苏敏, 等. 2015-2017年中国HIV暴露儿童艾滋病感染早期诊断检测情况分析[J]. 中华流行病学杂志, 2019, 40(9): 1111-1115. Qiao YP, Wang XY, Su M, et al. HIV early infant diagnosis test in HIV-exposed children in China, 2015-2017[J]. Chin J Epidemiol, 2019, 40(9): 1111-1115. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2019.09.017 |

| [17] |

Nosyk B, Montaner JSG, Colley G, et al. The cascade of HIV care in British Columbia, Canada, 1996-2011:a population-based retrospective cohort study[J]. Lancet Infect Dis, 2014, 14(1): 40-49. DOI:10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70254-8 |

| [18] |

Barth RE, Tempelman HA, Smelt E, et al. Long-term outcome of children receiving antiretroviral treatment in rural South Africa:substantial virologic failure on first-line treatment[J]. Pediatr Infect Dis J, 2011, 30(1): 52-56. DOI:10.1097/INF.0b013e3181ed2af3 |

| [19] |

Mugglin C, Wandeler G, Estill J, et al. Retention in care of HIV-infected children from HIV test to start of antiretroviral therapy:systematic review[J]. PLoS One, 2013, 8(2): e56446. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0056446 |

| [20] |

Alvarez-Uria G. Description of the cascade of care and factors associated with attrition before and after initiating antiretroviral therapy of HIV infected children in a cohort study in India[J]. Peer J, 2014, 2: e304. DOI:10.7717/peerj.304 |

| [21] |

Grinsztejn B, Hosseinipour MC, Ribaudo HJ, et al. Effects of early versus delayed initiation of antiretroviral treatment on clinical outcomes of HIV-1 infection:results from the phase 3 HPTN 052 randomised controlled trial[J]. Lancet Infect Dis, 2014, 14(4): 281-290. DOI:10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70692-3 |

| [22] |

Resino S, Resino R, Micheloud D, et al. Long-term effects of highly active antiretroviral therapy in pretreated, vertically HIV type 1-infected children:6 years of follow-up[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2006, 42(6): 862-869. DOI:10.1086/500412 |

| [23] |

Zhang FJ, Dou ZH, Ma Y, et al. Effect of earlier initiation of antiretroviral treatment and increased treatment coverage on HIV-related mortality in China:a national observational cohort study[J]. Lancet Infect Dis, 2011, 11(7): 516-524. DOI:10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70097-4 |

| [24] |

Penazzato M, Bendaud V, Nelson L, et al. Estimating future trends in paediatric HIV[J]. AIDS, 2014, 28(Suppl 4): S445-451. DOI:10.1097/QAD.0000000000000481 |

| [25] |

Melvin AJ, Mohan KM, Arcuino LA, et al. Clinical, virologic and immunologic responses of children with advanced human immunodeficiency virus type 1 disease treated with protease inhibitors[J]. Pediatr Infect Dis J, 1997, 16(10): 968-974. DOI:10.1097/00006454-199710000-00013 |

| [26] |

Krogstad P, Patel K, Karalius B, et al. Incomplete immune reconstitution despite virologic suppression in HIV-1 infected children and adolescents[J]. AIDS, 2015, 29(6): 683-693. DOI:10.1097/QAD.0000000000000598 |

| [27] |

Sandgaard KS, Lewis J, Adams S, et al. Antiretroviral therapy increases thymic output in children with HIV[J]. AIDS, 2014, 28(2): 209-214. DOI:10.1097/QAD.0000000000000063 |

| [28] |

Graney MJ, Bunting SM, Russell CK. HIV/AIDS medication adherence factors:inner-city clinic patient's self-reports[J]. Tenn Med, 2003, 96(2): 73-78. |

| [29] |

Elul B, Lahuerta M, Abacassamo F, et al. A combination strategy for enhancing linkage to and retention in HIV care among adults newly diagnosed with HIV in Mozambique:study protocol for a site-randomized implementation science study[J]. BMC Infect Dis, 2014, 14(1): 549. DOI:10.1186/s12879-014-0549-5 |

| [30] |

冯丽, 陆娟, 王凯, 等. 新疆儿童HIV/AIDS病人抗病毒治疗的免疫学因素分析[J]. 中国艾滋病性病, 2018, 24(11): 1091-1096. Feng L, Lu J, Wang K, et al. Analysis of immunological factors of antiviral therapy in HIV/AIDS children in Xinjiang[J]. Chin J AIDS STD, 2018, 24(11): 1091-1096. DOI:10.13419/j.cnki.aids.2018.11.06 |

2020, Vol. 41

2020, Vol. 41