文章信息

- 卢鹏, 刘巧, 竺丽梅, 孔雯, 丁晓艳, 周扬, 陆伟.

- Lu Peng, Liu Qiao, Zhu Limei, Kong Wen, Ding Xiaoyan, Zhou Yang, Lu Wei

- 中国东部地区结核菌素试验诊断结核病感染临界值的确定:基于人群的现况调查

- Selection of the cutoff value on tuberculin skin test in diagnosing tuberculosis infection: a population-based cross-sectional study in Eastern China

- 中华流行病学杂志, 2020, 41(3): 363-367

- Chinese Journal of Epidemiology, 2020, 41(3): 363-367

- http://dx.doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2020.03.016

-

文章历史

收稿日期: 2019-06-11

结核分枝杆菌潜伏性感染(latent tuberculosis infection,LTBI)是一种对结核分枝杆菌(Mycobacterium tuberculosis,MTB)抗原的持续免疫应答状态,没有临床表现为活动性结核(tuberculosis,TB)的证据[1]。LTBI的诊断没有金标准,目前指南推荐的用于诊断LTBI的有结核菌素试验(tuberculin skin test,TST)和γ-干扰素释放试验(interferon-γ release assays,IGRAs),包括QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube(QFT,Cellestis,Carnegie,Australia)和T-SPOTH.TB(Oxford Immunotec,Abingdon,UK)[2-4]。

自1908年以来,TST一直是检测结核分枝杆菌感染的标准方法,灵敏度在75%~90%[5-6]。由于TST与非结核分枝杆菌和卡介苗(Bacillus Calmette-Guerin,BCG)存在交叉反应,其假阳性是限制其应用的最主要问题[7]。为了弥补这一缺点,在各种指南中通过采取不同TST的临界值来降低假阳性[8-9]。然而,如果感染艾滋病毒或患有糖尿病等免疫系统缺陷疾病,尽管已知接种卡介苗,仍可使用较低的临界值。这加剧了结核菌素纯蛋白衍生物(purified protein derivative,PPD)结果解释的复杂性,造成许多局部变化和临床不确定性[10]。而IGRAs是一种基于血液标准的体外检测方法,其多肽覆盖了MTB特异性、BCG缺失的抗原ESAT-6和CFP-10,其特异性为98%~100%[11]。由于成本和复杂性,WHO于2011年发布了一份“负面”政策声明,警告不要将TST替换为IGRAs作为在中低收入国家中LTBI的检测方法[12]。

基于种种原因,TST仍是全球范围内应用最广泛的LTBI检测手段。但在中国等人群广泛接种BCG的国家,其临界值的确定却很少有人研究。为此,本研究在江苏省丹阳市开展一项现况调查,用QFT作为LTBI的金标准,来确定TST用于诊断LTBI的临界值。

对象与方法1.研究对象:2013年7月,在中国东部地区开展了基于全人群的现况调查。选取江苏省丹阳市东新村和白马村进行入户调查,纳入标准为年龄≥5岁、常住居民、完成血糖检查和结核病感染两项检测(TST和QFT)的受试者。常住居民的定义是在丹阳市连续居住≥6个月。排除标准为在基线调查时处于妊娠期以及确诊的活动性结核病患者。

对于符合条件的参与者由有经验的采访者通过调查问卷收集信息。收集每个参与者的信息,包括性别、年龄、吸烟状况、饮酒情况、卡介苗接种史和糖尿病患病史。

2.糖尿病的确定:使用WHO指南和最近中国糖尿病流行调查的方法来定义糖尿病:FPG≥7.0 mmol/L,糖负荷后2 h血糖≥11.1 mmol/L[13-14]。糖尿病是通过FPG检测、自我报告以及受试者的病历记录确定的。本研究在基线访视时采集受试者静脉血进行FPG检测。

本研究将糖尿病患者分为两组,根据糖尿病患者是否是新诊断分为有糖尿病史和新诊断糖尿病两组。有糖尿病史被定义为参与者通过医疗记录和自我报告确诊的糖尿病。如果参与者自我报告没有糖尿病,但病历显示有糖尿病,以病历结果为准。新诊断的糖尿病被定义为既往无糖尿病诊断的证据,但FPG检测结果呈阳性。

3.结核病潜伏性感染的确定:使用QFT(Qiagen;Valencia,California,United States)和TST用于基线访问时LTBI的诊断,以QFT诊断结果作为诊断LTBI的金标准。QFT反应≥0.35 IU/ml时认为其是结核病潜伏性感染者。在QFT检测后立即对同一受试者通过Mantoux方法进行TST检测,皮内注射0.1 ml 5个结核菌素单位纯化蛋白衍生物(祥瑞;中国北京)。在给药48~72 h后读取TST结果,并横向和纵向测量每位受试者前臂的硬结直径[6]。

4.统计学分析:在探索性数据分析中,定量资料根据是否符合正态分布,采用x±s和中位数及四分位数间距[M(P25~P75)]来描述定量资料,采用人数(%)来描述分类变量资料。用受试者工作特征曲线(receiver operating characteristic curve,ROC)来确定TST用于诊断LTBI的临界值。用OR值(95%CI)来衡量变量对LTBI的影响。以性别、年龄、吸烟状况、饮酒情况、BCG接种史和糖尿病患病史为自变量,建立二元logistic回归模型,以logistic预测概率法得出的P预测值作为综合指示指标来诊断LTBI,并用ROC曲线评价此二元logistic模型预报LTBI的能力。采用SPSS 23.0软件进行统计分析,P< 0.05为差异有统计学意义。

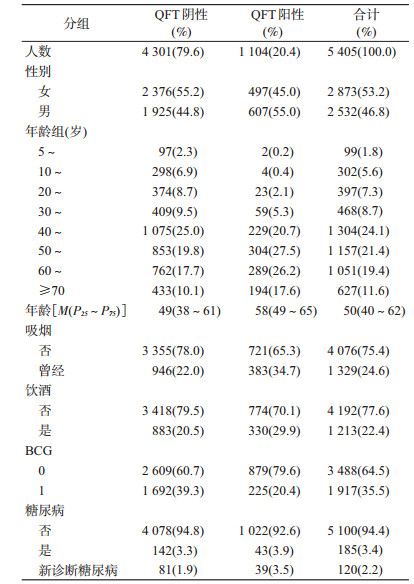

结果1.人口学特征:在8 734名符合条件的参与者中,有5 997人参与了基线调查(排除常住人口1 424人,< 5岁110人,孕妇4人,拒绝参加试验1 199人),排除592名(9.8%)参与者后(不签署知情同意书520人,不接受TST或QFT 12人,不确定的QFT结果57人,活动性肺结核3人),最终纳入5 405名符合条件的研究对象。研究对象的人口学特征见表 1。1 678名(31.0%)参与者≥60岁,401名(7.4%)参与者 < 20岁。1 329人(24.6%)自称吸烟或曾经吸烟,1 213名(22.4%)自称饮酒或曾经饮酒。有305例糖尿病患者,糖尿病患病率5.6%(95%CI:5.0%~6.3%),其中60.7%(95%CI:55.1%~66.2%;185人)有糖尿病史。在5 405名受试者中,经QFT试验,1 104名(20.4%)检测阳性。2 997名(55.4%)参与者PPD硬结直径≤5 mm;2 043名(37.8%)≥10 mm。

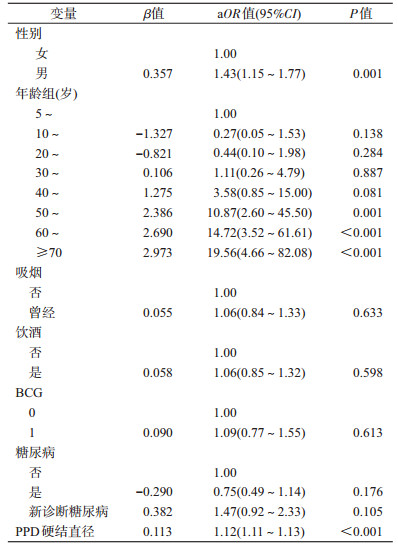

2.结核菌素皮肤试验的诊断价值:在5 405例患者中,PPD硬结直径为10.25 mm时诊断价值最高,其灵敏度为0.731,特异度为0.727;曲线下面积(area under the curve,AUC)为0.772(95%CI:0.755~ 0.788)。当PPD硬结直径为5.25 mm时,灵敏度为0.787,特异度为0.654(图 1)。将患者分为正常人和糖尿病患者时,两组硬结直径均在11.25 mm时其诊断价值达到最高,灵敏度和特异度分别为0.701、0.745和0.805、0.821(图 2)。当使用7.25 mm作为LTBI的临界值时,灵敏度(0.767)+特异度(0.679)与11.25 mm相等,而特异度(7.25 mm)远低于11.25 mm(0.679 vs. 0.745)。两组AUC分别为0.767(95%CI:0.749~0.784)和0.846(95%CI:0.790~0.903)。

|

| 图 1 5 405名受试者结核菌素试验ROC曲线 |

|

| 图 2 按糖尿病分组后结核菌素试验ROC曲线 |

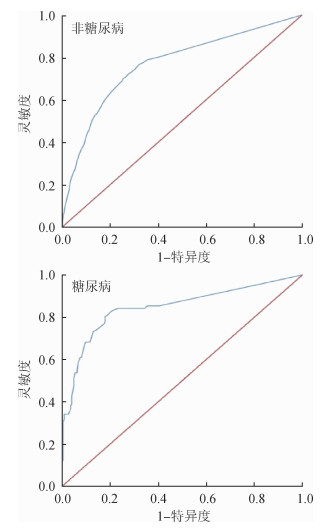

有糖尿病史组和新诊断糖尿病组两组硬结直径的临界值分别为10.25 mm和11.25 mm,其灵敏度和特异度分别为0.837、0.824和0.821、0.778,AUC分别为0.848(95%CI:0.769~0.927)和0.838(95%CI:0.755~0.922)(图 3)。

|

| 图 3 按诊断时间分组后结核菌素试验ROC曲线 |

3.多元logistic回归模型:在控制年龄、性别、卡介苗接种史、吸烟、饮酒和糖尿病患病后,高PPD硬结直径是LTBI较强的预测替代指标(aOR=1.12,95%CI:1.11~1.13,P < 0.001)(表 2)。预测值最高时预测概率的临界值为0.244,敏感度和特异度分别为0.688和0.868。当预测概率P≥0.224时,诊断其为LTBI。采用该截断点,其AUC=0.845(95%CI:0.831~0.858),符合率为83.11%(4 492/5 405)。

为实现2035年消除结核病的目标,准确识别和治疗LTBI对结核控制和消除至关重要。因此,发现一种快速、准确以及操作方便的诊断LTBI的方法至关重要。目前用于诊断LTBI的应用最广泛的方法主要为TST和IGRAs。QFT和T-SPOT应用MTB特异性、BCG缺失的ESAT-6和CFP-10作为抗原,除MTB外仅存在于少数非结核分枝杆菌中(如堪萨斯分支杆菌等),而在任何一种BCG疫苗中都不存在,所以其特异性很高[7, 15-17]。但其需要采血、需要专门的实验室、对实验室人员要求比较高,同时费用也比较大,因此限制其应用[7]。而应用最广泛的TST恰恰相反,其可由医护人员、护理人员或辅助医疗人员进行操作,不需要专门实验室,费用也比较少,但其特异性比较低,结果解释也比较复杂[5-6]。因此,如何降低TST诊断LTBI假阳性就显得尤为重要。在这项基于中国东部人群的现况调查,本研究发现,无论是健康人、有糖尿病史和新诊断糖尿病患者,TST硬结直径在10~12 mm之间其诊断价值最高,可以大大降低TST诊断LTBI的假阳性。

TST是目前用于诊断结核病潜伏性感染最常用的诊断方法,但由于TST与非结核分枝杆菌和卡介苗存在交叉反应,其假阳性是限制其应用的最主要的问题[7]。为了弥补这一缺点,在各种指南中通过采取不同的TST的临界值来降低假阳性[8-9]。本研究发现选取10~12 mm作为TST诊断LTBI的临界值时,其诊断价值最高,特异度均>80%,这与国内外研究结果一致。一篇Meta分析结果显示,当TST临界值为10~15 mm时的阳性结果为真阳性[18];Erol等[19]研究发现,TST用于诊断LTBI的假阳性率会随着临界值的增大而降低;Farhat等[20]的研究也发现,用10 mm代替5 mm作为诊断LTBI的临界值,其假阳性大大降低。因此,在BCG普遍接种及非结核分枝杆菌高发病率地区,选取≥10 mm作为临界值,可以大大降低TST的低特异度。

本研究还发现,在糖尿病人群中用TST诊断LTBI的临界值也是在10 mm时其诊断价值达到最高,这与其他研究结果不太一致。有研究表明,糖尿病患者会导致TST诊断LTBI的灵敏度降低,因此,应该选用较低的临界值[21];也有研究表明免疫缺陷并不会降低其敏感性[19, 22],这可能是由于江苏省位于东部靠海地区,非结核分枝杆菌流行率较高导致[23]。尽管有研究表明非结核分枝杆菌不是导致TST诊断LTBI假阳性的主要原因,但是在中国东部地区非结核分枝杆菌对TST的影响不能忽略。

本研究存在局限性。首先,由于缺乏金标准,本研究采用QFT作为LTBI诊断的金标准,因此可能由于假阴性而低估人群中感染率;其次,本研究并没有收集人群的艾滋病感染情况,但在江苏省由于艾滋病患病率较低,因此对本研究影响不大。

本研究证实,以10~12 mm作为结核病潜伏性感染诊断的临界值可以大大提高结核菌素试验的特异性,降低操作人员对结果判读的复杂性。

利益冲突 所有作者均声明不存在利益冲突

| [1] |

Mack U, Migliori GB, Sester M, et al. LTBI:latent tuberculosis infection or lasting immune responses to M.tuberculosis? A TBNET consensus statement[J]. Eur Respirat J, 2009, 33(5): 956-973. DOI:10.1183/09031936.00120908 |

| [2] |

Abubakar I, Griffiths C, Ormerod P, et al. Diagnosis of active and latent tuberculosis:summary of NICE guidance[J]. BMJ, 2012, 345: e6828. DOI:10.1136/bmj.e6828 |

| [3] |

Denkinger CM, Dheda K, Pai M. Guidelines on interferon-γ release assays for tuberculosis infection:concordance, discordance or confusion?[J]. Clin Microbiol Infect, 2011, 17(6): 806-814. DOI:10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03555.x |

| [4] |

Pai M, Riley LW, Colford JM Jr. Interferon-γ assays in the immunodiagnosis of tuberculosis:a systematic review[J]. Lancet Infect Dis, 2004, 4(12): 761-776. DOI:10.1016/S1473-3099(04)01206-X |

| [5] |

Snider DE Jr. The tuberculin skin test[J]. Am Rev Respir Dis, 1982, 125(3 Pt 2): 108-118. |

| [6] |

Huebner RE, Schein MF, Bass JB Jr. The tuberculin skin test[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 1993, 17(6): 968-975. DOI:10.1093/clinids/17.6.968 |

| [7] |

Pai M, Denkinger CM, Kik SV, et al. Gamma interferon release assays for detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection[J]. Clin Microbiol Rev, 2014, 27(1): 3-20. DOI:10.1128/CMR.00034-13 |

| [8] |

WHO. WHO Guidelines approved by the guidelines review committee[M]//WHO. Guidance for National Tuberculosis Programmes on the Management of Tuberculosis in Children. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2014.

|

| [9] |

Department of Health. Diagnosis of tuberculosis[M]//Department of Health. The South African National Tuberculosis Control Programme: Practical Guidelines. Pretoria: Department of Health, 2004: 45-53.

|

| [10] |

Aggerbeck H, Giemza R, Joshi P, et al. Randomised clinical trial investigating the specificity of a novel skin test (C-Tb) for diagnosis of M. tuberculosis infection[J]. PLoS One, 2013, 8(5): e64215. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0064215 |

| [11] |

Diel R, Goletti D, Ferrara G, et al. Interferon-γ release assays for the diagnosis of latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection:a systematic review and Meta-analysis[J]. Eur Respirat J, 2011, 37(1): 88-99. DOI:10.1183/09031936.00115110 |

| [12] |

World Health Organization. Use of tuberculosis interferon-gamma release assays (IGRAs) in low-and middle-income countries:policy statement[M]. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2011.

|

| [13] |

Xu Y, Wang LM, He J, et al. Prevalence and control of diabetes in Chinese adults[J]. JAMA, 2013, 310(9): 948-959. DOI:10.1001/jama.2013.168118 |

| [14] |

Alberti KGMM, Zimmet PZ. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1:diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus provisional report of a WHO consultation[J]. Diabet Med, 1998, 15(7): 539-553. DOI:10.1002/(SICI)1096-9136(199807)15:7<539:AID-DIA668>3.0.CO;2-S |

| [15] |

Brock I, Munk ME, Kok-Jensen A, et al. Performance of whole blood IFN-γ test for tuberculosis diagnosis based on PPD or the specific antigens ESAT-6 and CFP-10[J]. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis, 2001, 5(5): 462-467. |

| [16] |

Johnson PDR, Stuart RL, Grayson ML, et al. Tuberculin-purified protein derivative-, MPT-64-, and ESAT-6-stimulated gamma interferon responses in medical students before and after Mycobacterium bovis BCG vaccination and in patients with tuberculosis[J]. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol, 1999, 6(6): 934-937. DOI:10.1128/CDLI.6.6.934-937.1999 |

| [17] |

Mori T, Sakatani M, Yamagishi F, et al. Specific detection of tuberculosis infection:an interferon-γ-based assay using new antigens[J]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2004, 170(1): 59-64. DOI:10.1164/rccm.200402-179OC |

| [18] |

Wang L, Turner MO, Elwood RK, et al. A Meta-analysis of the effect of Bacille Calmette Guérin vaccination on tuberculin skin test measurements[J]. Thorax, 2002, 57(9): 804-809. DOI:10.1136/thorax.57.9.804 |

| [19] |

Erol S, Ciftci FA, Ciledag A, et al. Do higher cut-off values for tuberculin skin test increase the specificity and diagnostic agreement with interferon gamma release assays in immunocompromised Bacillus Calmette-Guérin vaccinated patients?[J]. Adv Med SCI, 2018, 63(2): 237-241. DOI:10.1016/j.advms.2017.12.001 |

| [20] |

Farhat M, Greenaway C, Pai M, et al. False-positive tuberculin skin tests:what is the absolute effect of BCG and non-tuberculous mycobacteria?[J]. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis, 2006, 10(11): 1192-1204. |

| [21] |

Choi JC, Jarlsberg LG, Grinsdale JA, et al. Reduced sensitivity of the QuantiFERON® test in diabetic patients with smear-negative tuberculosis[J]. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis, 2015, 19(5): 582-588. DOI:10.5588/ijtld.14.0553 |

| [22] |

Auguste P, Tsertsvadze A, Pink J, et al. Comparing interferon-gamma release assays with tuberculin skin test for identifying latent tuberculosis infection that progresses to active tuberculosis:systematic review and Meta-analysis[J]. BMC Infect Dis, 2017, 17(1): 200. DOI:10.1186/s12879-017-2301-4 |

| [23] |

Gao L, Lu W, Bai LQ, et al. Latent tuberculosis infection in rural China:baseline results of a population-based, multicentre, prospective cohort study[J]. Lancet Infect Dis, 2015, 15(3): 310-319. DOI:10.1016/S1473-3099(14)71085-0 |

2020, Vol. 41

2020, Vol. 41