文章信息

- 游玥玥, 宋岩, 王沫涵, 张丽丽, 白微, 于玮莹, 于雅琴, 寇长贵.

- You Yueyue, Song Yan, Wang Mohan, Zhang Lili, Bai Wei, Yu Weiying, Yu Yaqin, Kou Changgui

- 生命早期饥荒暴露与成年期高血压患病风险的关联分析

- Exposure to famine in fetus and infant period and risk for hypertension in adulthood

- 中华流行病学杂志, 2020, 41(1): 74-78

- Chinese Journal of Epidemiology, 2020, 41(1): 74-78

- http://dx.doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2020.01.014

-

文章历史

收稿日期: 2019-04-28

2. 深圳市南山区慢性病防治院健康教育科 518000

2. Health Education Division, Center for Chronic Disease Control, Nanshan District, Shenzhen 518000, China

我国高血压患病率在过去的几十年居高不下。有研究显示高血压与环境压力、饮食改变、缺乏锻炼以及吸烟有关[1]。既往研究表明,胎儿营养不良或者不良暴露与成年期某些退行性慢性病的易感性增加密切相关[2]。健康和疾病的发展起源学说认为,在关键生长阶段,包括胎儿时期、婴儿期和儿童时期营养不良,可能导致身体结构、新陈代谢和生理的永久性变化,这种改变会增加中老年常见疾病如高血压、心血管疾病和2型糖尿病的患病风险[3-4]。动物实验数据表明,胎儿营养不良会导致出生时体重不足、影响胆固醇水平以及成年期的血压升高[5-8]。但是,由于伦理和实践的原因,国外研究结果尚存争议[9-12],而国内研究数据较少[13-17],尚缺乏足够的证据证明产前营养不良会直接影响人类成年期的患病风险。本研究旨在基于2012年在吉林省成年居民中开展的横断面调查数据,探讨胎儿及婴儿时期暴露于饥荒(1959-1961年)的人群成年后高血压的患病风险。

对象与方法1.研究对象:数据源于2012年开展的吉林省成年人慢性病及其危险因素调查[18],采用多阶段分层随机整群抽样方法,最终完成样本量21 435人,有效应答率为84.9%。按照中国饥荒发生年份,纳入出生于1956-1965年之间的5 960人。

2.研究方法:饥荒暴露最常见的是根据出生日期划分为3组,但根据之前的研究[19-20],本研究将研究对象分成4组:儿童早期暴露组(1956年1月至1958年12月)、胎儿期暴露组(1959年1月至1961年12月)、过渡组(1962年1-12月)和未暴露组(1963年1月1日至1965年12月31日)。平均年龄分别为54、51、49和47岁。从数据库中选取研究对象一般情况(包括出生日期、体重、身高、腰围等)、吸烟、饮酒、疾病史等信息。

3.诊断标准:中心性肥胖定义为腰围男性≥85 cm,女性≥80 cm。符合以下标准之一,则被定义为高血压:①自我报告既往被医生明确诊断为高血压;②目前使用降压药;③SBP>140 mmHg(1 mmHg=0.133 kPa)或DBP>90 mmHg。

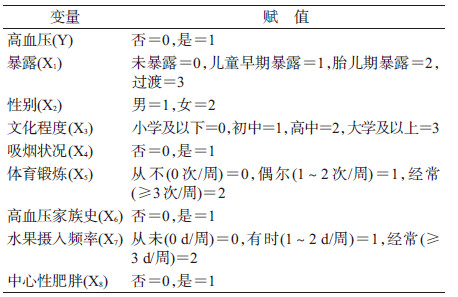

4.统计学分析:数据统计分析使用SPSS 24.0软件。分类变量用率(%)表示,连续变量用x±s表示,组间基本特征的比较运用方差分析或χ2检验。采用多元logistic回归模型估计暴露与未暴露高血压的OR值和95%CI。将年龄、性别、吸烟状况等纳入调整模型(模型1:调整年龄和BMI;模型2:在模型1基础上调整性别、文化程度、吸烟状况、体育锻炼、高血压家族史及水果摄入频率;模型3:在模型2基础上调整中心性肥胖)。变量及赋值见表 1,以双侧P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。

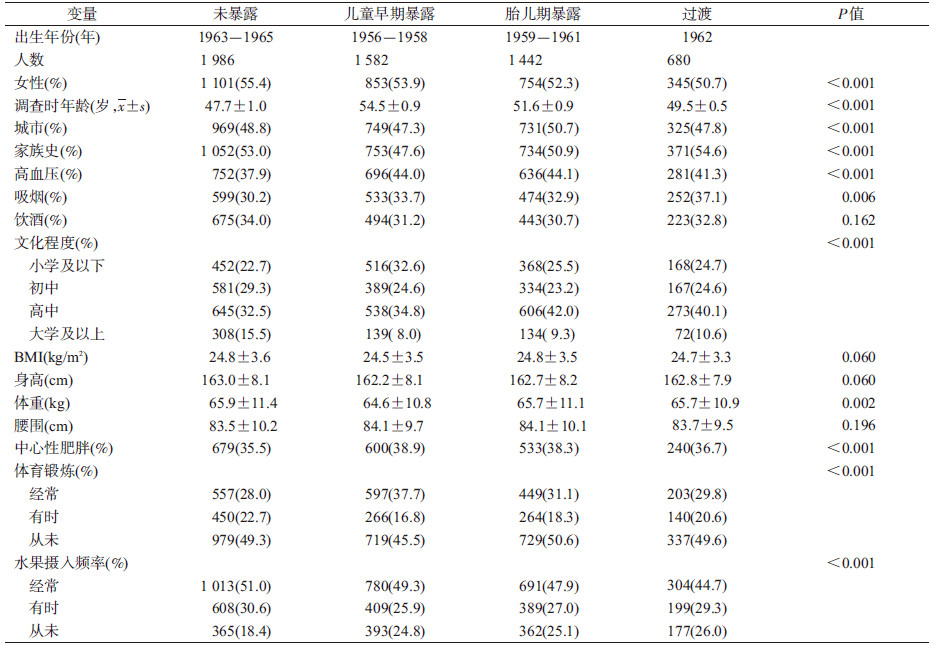

1.一般情况:本研究共纳入5 690人,其中男性2 637人,女性3 053人。儿童早期暴露组、胎儿期暴露组、过渡组、未暴露组成年期高血压患病率分别为44.0%、44.1%、41.3%和37.9%。不同组间体育锻炼频率和水果摄入频率分布不平衡。此外,不同组的BMI、酒精摄入量、身高和腰围差异无统计学意义。饥荒暴露对象的文化程度低于未暴露组。见表 2。

2.饥荒和成年期高血压的关联:在调整年龄、BMI、性别、文化程度、吸烟状况、体育锻炼、高血压家族史、水果摄入频率、肥胖后,与未暴露相比,儿童早期暴露(OR=1.360,95%CI:1.102~1.679)和胎儿期暴露(OR=1.249,95%CI:1.049~1.486)差异有统计学意义(表 3)。

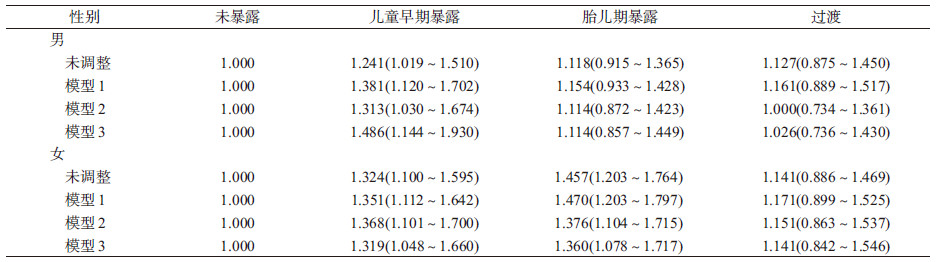

3.性别差异分析:按照性别分层后,男性饥荒未暴露、儿童早期暴露、胎儿期暴露以及过渡组的高血压患病率分别为43.6%、49.0%、46.4%和46.6%,女性的高血压患病率分别为33.2%、39.7%、42.0%和36.2%。分层分析结果表明,女性胎儿期饥荒暴露与未暴露相比高血压患病风险增加了36.0%(95%CI:7.8%~71.7%)。儿童早期饥荒暴露与未暴露相比高血压患病风险增加了31.9%(95%CI:4.8%~66.0%)(表 4)。

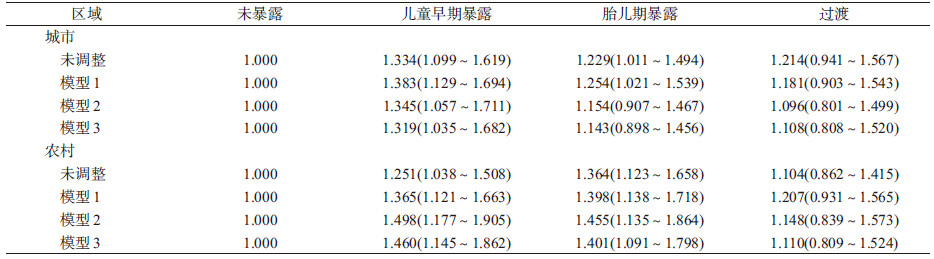

4.城乡差异分析:按照城乡分层后,城市地区饥荒未暴露、儿童早期暴露、胎儿期暴露以及过渡组的高血压患病率分别为38.4%、45.4%、43.4%和43.1%,农村地区高血压患病率分别为37.4%、42.7%、44.9%和39.7%。在农村地区,与未暴露相比,胎儿期暴露(OR=1.401,95%CI:1.091~1.798)和儿童早期暴露(OR=1.460,95%CI:1.145~1.862)的差异有统计学意义(表 5)。

研究发现,妊娠期和幼儿期的营养状况对成年期高血压的发展至关重要。女性胎儿期和幼儿期营养不良引起成年期高血压风险升高。但在男性中,胎儿期饥荒对成年期高血压没有影响。与未暴露人群相比,农村人群中也发现了胎儿期和幼儿期营养不良与成年期高血压之间的联系。

本研究结果表明,胎儿期营养不良与成年后高血压风险显著增加有关。尼日利亚的队列研究结果表明,胎儿和婴儿营养不良与40岁的尼日利亚人患高血压和葡萄糖耐量受损的风险显著增加有关[20]。荷兰的饥荒研究结果表明,胎儿期间暴露在饥荒中可能易引起中年高血压(OR=1.44,95%CI:1.04~2.00)[21]。我国研究也发现,胎儿期饥荒暴露会增加成年后高血压的患病风险[19, 22]。

在性别差异的研究中发现,1959-1961年的饥荒在一定程度上影响了女性胎儿成年后的高血压,但对男性胎儿没有影响。中国饥荒对不同性别影响的原因尚不清楚:首先,已有动物研究发现,胎儿期营养不足对雌性健康的影响大于雄性[23-24]。其次,死亡选择假设认为男性死亡率高于女性,尤其是在婴儿期,这一定程度上也解释了饥荒暴露的女性在以后的生活中的健康状况更差[25]。第三,由于传统价值观中的“重男轻女”的错误思想影响,粮食短缺的情况下,父母优先考虑儿子的食物摄入,导致女儿出现更严重的食物短缺,造成其早年生活营养不良。

此外,仅在农村发现暴露和儿童早期暴露组成年期患高血压的风险增加,这可能是由于农村的粮食供应系统偏差。无论当年的产出如何,城市人口可以通过国家控制的粮食配给得到保护,而农民的食物保障困难[26]。在饥荒期间,尽管农村和城市地区粮食供应均有所下降,但农村地区的这种情况更加严重,城市居民较少受到饥荒的影响,另外许多农村居民每日摄入的热量较少,加剧了原有的城乡人均粮食供应量差异[27]。

综上所述,在胎儿发育期间暴露于饥荒可增加成年期高血压的患病危险,饥荒对高血压的影响具有长期性,生命早期均衡营养对预防成年后高血压的发生具有重要意义。

利益冲突 所有作者均声明不存在利益冲突

| [1] |

Bu S, Ruan D, Yang Z, et al. Sex-specific prevalence of diabetes and cardiovascular risk factors in the middle-aged population of China:a subgroup analysis of the 2007-2008 China national diabetes and metabolic disorders study[J]. PLoS One, 2015, 10(9): e0139039. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0139039 |

| [2] |

Barker DJP. Maternal nutrition, fetal nutrition, and disease in later life[J]. Nutrition, 1997, 13(9): 807-813. DOI:10.1016/S0899-9007(97)00193-7 |

| [3] |

Gluckman PD, Hanson MA, Bateson P, et al. Towards a new developmental synthesis:adaptive developmental plasticity and human disease[J]. Lancet, 2009, 373(9675): 1654-1657. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60234-8 |

| [4] |

Hales CN, Barker DJP. The thrifty phenotype hypothesis:type 2 diabetes[J]. Brit Med Bull, 2001, 60(1): 5-20. DOI:10.1093/bmb/60.1.5 |

| [5] |

Langley SC, Jackson AA. Increased systolic blood pressure in adult rats induced by fetal exposure to maternal low protein diets[J]. Clin Sci, 1994, 86(2): 217-222. DOI:10.1042/cs0860217 |

| [6] |

Bol V, Desjardins F, Reusens B, et al. Does early mismatched nutrition predispose to hypertension and atherosclerosis, in male mice?[J]. PLoS One, 2010, 5(9): e12656. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0012656 |

| [7] |

Pennington JS, Pennington SN. Rat adult offspring serum lipoproteins are altered by maternal consumption of a liquid diet[J]. Lipids, 2006, 41(4): 357-363. DOI:10.1007/s11745-006-5106-6 |

| [8] |

Lucas A, Baker BA, Desai M, et al. Nutrition in pregnant or lactating rats programs lipid metabolism in the offspring[J]. Brit J Nutr, 1996, 76(4): 605-612. DOI:10.1079/BJN19960066 |

| [9] |

Koupil I, Shestov DB, Sparén P, et al. Blood pressure, hypertension and mortality from circulatory disease in men and women who survived the siege of Leningrad[J]. Eur J Epidemiol, 2007, 22(4): 223-234. DOI:10.1007/s10654-007-9113-6 |

| [10] |

Stanner SA, Bulmer K, Andrès C, et al. Does malnutrition in utero determine diabetes and coronary heart disease in adulthood? Results from the Leningrad siege study, a cross sectional study[J]. BMJ, 1997, 315(7119): 1342-1348. DOI:10.1136/bmj.315.7119.1342 |

| [11] |

Ravelli ACJ, van der Meulen JHP, Michels RPJ, et al. Glucose tolerance in adults after prenatal exposure to famine[J]. Lancet, 1998, 351(9097): 173-177. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(97)07244-9 |

| [12] |

de Rooij SR, Painter RC, Phillips DIW, et al. Impaired insulin secretion after prenatal exposure to the Dutch famine[J]. Diabetes Care, 2006, 29(8): 1897-1901. DOI:10.2337/dc06-0460 |

| [13] |

Mu R, Zhang XB. Why does the Great Chinese Famine affect the male and female survivors differently? Mortality selection versus son preference[J]. Eco Hum Biol, 2011, 9(1): 92-105. DOI:10.1016/j.ehb.2010.07.003 |

| [14] |

Yu CZ, Wang J, Li Y, et al. Exposure to the Chinese famine in early life and hypertension prevalence risk in adults[J]. J Hypertens, 2017, 35(1): 63-68. DOI:10.1097/HJH.0000000000001122 |

| [15] |

Li YN, He Y, Qi L, et al. Exposure to the Chinese famine in early life and the risk of hyperglycemia and type 2 diabetes in adulthood[J]. Diabetes, 2010, 59(10): 2400-2406. DOI:10.2337/db10-0385 |

| [16] |

Huang C, Li Z, Wang M, et al. Early life exposure to the 1959-1961 Chinese famine has long-term health consequences[J]. J Nutr, 2010, 140(10): 1874-1878. DOI:10.3945/jn.110.121293 |

| [17] |

Chen JP, Peng B, Tang L, et al. Fetal and infant exposure to the Chinese famine increases the risk of fatty liver disease in Chongqing, China[J]. J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2016, 31(1): 200-205. DOI:10.1111/jgh.13044 |

| [18] |

Wang SB, D'Arcy C, Yu YQ, et al. Prevalence and patterns of multimorbidity in northeastern China:a cross-sectional study[J]. Public Health, 2015, 129(11): 1539-1546. DOI:10.1016/j.puhe.2015.06.013 |

| [19] |

Wang ZH, Li CW, Yang ZP, et al. Infant exposure to Chinese famine increased the risk of hypertension in adulthood:results from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study[J]. BMC Public Health, 2016, 16(1): 435. DOI:10.1186/s12889-016-3122-x |

| [20] |

Hult M, Tornhammar P, Ueda P, et al. Hypertension, diabetes and overweight:looming legacies of the Biafran famine[J]. PLoS One, 2010, 5(10): e13582. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0013582 |

| [21] |

Stein AD, Zybert PA, van der Pal-de Bruin K, et al. Exposure to famine during gestation, size at birth, and blood pressure at age 59 y:evidence from the Dutch Famine[J]. Eur J Epidemiol, 2006, 21(10): 759-765. DOI:10.1007/s10654-006-9065-2 |

| [22] |

Wang PX, Wang JJ, Lei YX, et al. Impact of fetal and infant exposure to the Chinese great famine on the risk of hypertension in adulthood[J]. PLoS One, 2012, 7(11): e49720. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0049720 |

| [23] |

Zambrano E, Martínez-Samayoa PM, Bautista CJ, et al. Sex differences in transgenerational alterations of growth and metabolism in progeny (F2) of female offspring (F1) of rats fed a low protein diet during pregnancy and lactation[J]. J Physiol, 2005, 566(1): 225-236. DOI:10.1113/jphysiol.2005.086462 |

| [24] |

Zambrano E, Bautista CJ, Deás M, et al. A low maternal protein diet during pregnancy and lactation has sex- and window of exposure-specific effects on offspring growth and food intake, glucose metabolism and serum leptin in the rat[J]. J Physiol, 2006, 571(1): 221-230. DOI:10.1113/jphysiol.2005.100313 |

| [25] |

Oksuzyan A, Juel K, Vaupel JW, et al. Men:good health and high mortality, Sex differences in health and aging[J]. Aging Clin Exp Res, 2008, 20(2): 91-102. DOI:10.1007/bf03324754 |

| [26] |

Sen A. Ingredients of famine analysis:availability and entitlements[J]. Q J Econ, 1981, 96(3): 433-464. DOI:10.2307/1882681 |

| [27] |

Song SG. Does famine have a long-term effect on cohort mortality? Evidence from the 1959-1961 Great Leap Forward Famine in China[J]. J Biosoc Sci, 2009, 41(4): 469-491. DOI:10.1017/S0021932009003332 |

2020, Vol. 41

2020, Vol. 41