文章信息

- 毕媛, 覃玉, 苏健, 崔岚, 杜文聪, 缪伟刚, 李晓波, 周金意.

- Bi Yuan, Qin Yu, Su Jian, Cui Lan, Du Wencong, Miao Weigang, Li Xiaobo, Zhou Jinyi.

- 江苏省心血管病高危人群颈动脉斑块流行及影响因素分析

- Prevalence and influencing factors of carotid plaque in population at high-risk for cardiovascular disease in Jiangsu province

- 中华流行病学杂志, 2019, 40(11): 1432-1438

- Chinese Journal of Epidemiology, 2019, 40(11): 1432-1438

- http://dx.doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2019.11.017

-

文章历史

收稿日期: 2019-04-04

2. 江苏省疾病预防控制中心慢性非传染病防制所, 南京 210009

2. Department of Non-communicable Chronic Disease Control and Prevention, Jiangsu Provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Nanjing 210009, China

近年来,我国城乡居民心血管病(cardiovascular disease,CVD)患病率及死亡率呈上升趋势,2017年心血管病死亡占居民死因构成40%以上,是中国居民的首要死亡原因[1]。心血管病的本质是动脉粥样硬化(atherosclerosis,AS),颈动脉斑块(carotid plaques,CP)可作为亚临床AS的替代标志物[2]。AS的发展过程缓慢且持续时间长,因此针对AS进行一级预防显得尤为重要。超声检测颈动脉内膜中层厚度(carotid intima-media thickness,cIMT)和CP的结果与组织病理检查一致性较好,可作为AS的早期无创性评价指标[3]。

目前,关于CP的研究主要集中在脑卒中高危人群[4-5]。本研究对江苏省心血管病高危人群CP的流行概况及影响因素进行研究,以期为心血管病的发病风险预测及其在亚临床AS阶段的防治提供科学依据。

对象与方法1.研究对象:研究人群来自“中国心血管病高危人群早期筛查与综合干预项目”中江苏省的人群信息。该项目于2015-2016年对江苏省常州市和淮安市区、徐州市贾汪区、苏州市常熟市、南通市海安市和连云港市东海县6个项目点71 511名35~75岁常住居民进行初筛调查,满足以下4项标准之一即为心血管病高危对象:①有以下任一疾病史或治疗史:心肌梗死史、缺血型或出血型脑卒中史、经皮冠状动脉介入治疗史、冠状动脉搭桥史;②SBP≥160 mmHg(1 mmHg=0.133 kPa)或DBP≥100 mmHg;③LDL-C≥4.14 mmol/L或HDL-C<0.78 mmol/L;④根据WHO《心血管风险评估和管理指南》的风险评估预测图进行评估,10年CVD患病风险≥20%[6]。共筛查出18 520例高危对象,排除自报心脑血管病史者1 616例(包括心肌梗死病史、冠心病病史、脑卒中病史、冠脉介入治疗史、冠脉搭桥手术史)、未进行颈动脉超声检测者3 898例以及资料不全者1 614例,最终11 392例心血管病高危人群纳入本研究。本研究通过国家心血管病中心伦理委员会审查,受访者均签署知情同意书。

2.研究方法:

(1)初筛调查内容及方法:问卷调查由经过专业培训的调查员对初筛对象进行面对面调查,内容包括社会人口学信息(性别、年龄、城乡、婚姻状况、文化程度、家庭年收入)、吸烟、饮酒以及疾病史等心血管病相关危险因素情况。其中,吸烟为调查时存在吸烟行为者。

体格检查采用电子身高体重仪,测量前筛查对象脱去鞋帽,着轻便衣物。腰围测量采用皮软尺水平环绕腹部,放置在髂前上嵴和第12肋下缘连线的中点位置。以中国肥胖工作组为依据,将BMI定义为体重(kg)除以身高(m)的平方[7]。

血压测量采用HEM-7430型电子血压计(日本欧姆龙公司)。每名筛查对象静坐5 min后,2次测量其右上臂血压。如果前后2次SBP差值>10 mmHg,进行第3次测量。记录后2次的血压和心率值,并取其平均值。脉压差定义为平均SBP与平均DBP的差值。采集6 ml空腹静脉血,使用PD-G001-2型快速血糖检测仪(中国台湾百捷公司)进行FPG测定。血脂检测采用Cardiocheck PA型快速血脂检测仪(美国卡迪克公司),测定TC、TG、HDL-C和LDL- C。依据《中国高血压防治指南》[8],将高血压定义为平均SBP≥140 mmHg或平均DBP≥90 mmHg,或自报在过去2周内服用降压药物。与WHO的诊断标准相同,糖尿病被定义为在至少8 h未进食的状态下,FPG≥7 mmol/L或自报在过去2周内服用降糖药物[9]。血脂异常的诊断标准根据《中国成人血脂异常防治指南2016》[10],定义为血清中TC≥6.2 mmol/L或TG≥2.3 mmol/L或HDL-C<1.0 mmol/L或LDL-C≥4.1 mmol/L,或自报在过去2周内服用降脂药物。

(2)颈动脉超声检测评估方法:各项目点的超声医生均接受过正规专业培训且有5年以上心血管超声工作经验,在项目开始之前每位超声医生提交2例颈动脉超声图像及报告至国家心血管病中心审核,审核通过后方可进行超声检查。超声检测分别观察颈总动脉、分叉处、颈内及颈外动脉内膜显示情况,依次测量左右两侧3段血管共6个点的cIMT,观察并记录是否存在斑块以及斑块数量[单发和多发(≥2)],多发定义为斑块负担(carotid burden,CB)。cIMT≥1.0 mm是颈动脉狭窄早期改变的标准,当1.0 mm≤cIMT<1.5 mm时,认定为内膜增厚[11]。当cIMT≥1.5 mm,或比临近cIMT增厚>0.5 mm,或>50%,凸向管腔,即认为斑块形成[12]。狭窄定义为斑块导致管腔缩小,依据北美症状性颈动脉内膜切除术分级法的诊断标准,狭窄程度<50%为轻度,50%~69%为中度,≥70%为重度,由专人于横切和纵切观察并判断是否狭窄并记录狭窄程度和狭窄部位[13]。当各点cIMT均<1.0 mm时判定为正常,否则为异常。

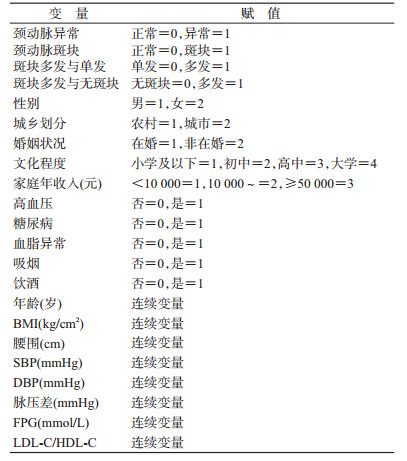

3.统计学分析:使用SPSS 22.0软件进行统计学分析。符合正态分布的连续变量使用x±s表示,其组间比较采用方差分析,不符合正态分布的连续变量使用M(P25~P75)表示,采用Kruskal-Wallis H检验进行组间比较。分类变量以频数和百分比(%)表示,组间比较采用χ2检验。利用多因素logistic回归模型分析比较颈动脉异常、斑块和CB的相关影响因素,变量赋值见表 1。将单因素分析中有统计学意义的变量纳入模型中。采用逐步向前法筛选变量,进行多因素logistic回归分析。在多因素分析中,将所有连续变量进行Z值函数转换,表示1个标准差改变带来的相应因变量的改变。以P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。

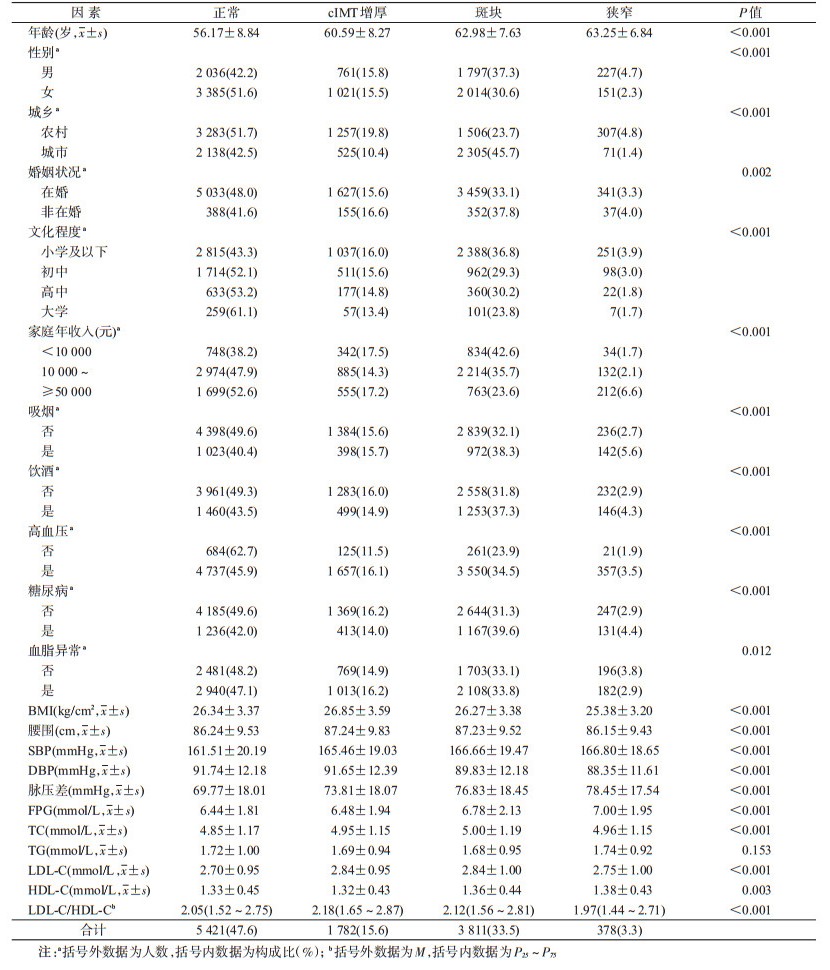

1.一般情况:11 392例调查对象中,男性4 821例(42.3%),女性6 571例(57.7%),年龄(59.4±8.9)岁。城市居民5 039例(44.2%),非在婚者932例(8.2%),文化程度在小学及以下6 491例(57.0%),家庭年收入<10 000元1 958例(17.2%)(表 2)。其中,高龄、男性、城市居民、非在婚者、文化程度和家庭年收入较低者cIMT增厚、斑块或狭窄的检出率较高,差异均有统计学意义(P<0.01)。

2.颈动脉超声检测异常的单因素分析:调查人群中,吸烟、饮酒人群中颈动脉超声检测异常分别有1 512例(59.6%)和1 898例(56.5%),高血压、糖尿病和血脂异常人群中颈动脉超声检测异常分别有5 564例(54.1%)、1 711例(58.0%)和3 303例(52.9%)。此外,颈动脉超声检测异常人群的BMI(kg/cm2)和腰围(cm)分别为26.39和87.16,血压、血糖、血脂各指标见表 2。在颈动脉超声检测中检查结果正常5 421例(47.6%),异常5 971例(52.4%),包括cIMT增厚1 782例(15.6%),斑块3 811例(33.5%),狭窄378例(3.3%)。其中,BMI、腰围、吸烟、饮酒、高血压、糖尿病、血脂异常(TG除外)在结果中的分布差异均有统计学意义(P<0.02)。见表 2。

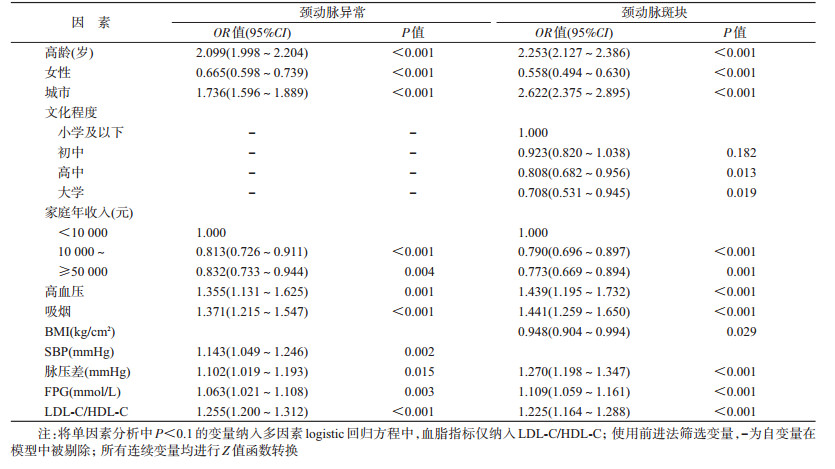

3.颈动脉超声检测异常的多因素分析:以单因素分析结果为依据,将相关因素纳入logistic回归模型。颈动脉异常组和CP组分别与正常组进行比较显示,高龄、城市居民、高血压、吸烟、脉压差增大、FPG、LDL-C/HDL-C上升增加颈动脉异常和CP发生的风险,而女性、较高的家庭年收入则降低其风险。随着SBP升高,颈动脉异常的发生率增高。随着文化程度的升高,CP患病率降低。BMI每增加1个标准差,CP患病风险降低5.2%(OR=0.948,95%CI:0.904~0.994),见表 3。

4. CB的多因素分析:将与CP负担(CP≥2)有关的因素纳入logistic回归分析中。结果显示,增加CB形成风险的可能因素包括高龄(OR=2.592,95%CI:2.384~2.818)、城市居民(OR=5.263,95%CI:4.569~6.063)、高血压(OR=1.582,95%CI:1.168~2.144)、糖尿病(OR=1.493,95%CI:1.301~1.714)、吸烟(OR=1.557,95%CI:1.308~1.854)、脉压差(OR=1.491,95%CI:1.378~1.614)、LDL-C/HDL-C(OR=1.244,95%CI:1.163~1.331),而降低其风险的相关因素有女性(OR=0.477,95%CI:0.405~0.563)、大学(OR=0.541,95%CI:0.349~0.838)、较高的家庭年收入(OR=0.650,95%CI:0.532~0.793)以及高BMI(OR=0.890,95%CI:0.833~0.951)。在斑块单发的人群中,增加形成斑块负担风险的因素与无斑块人群并无差异,女性(OR=0.620,95%CI:0.524~0.733)、较高的家庭年收入者(OR=0.709,95%CI:0.577~0.871)则降低斑块由单发变为多发的风险,见表 4。

本研究结果显示,江苏省心血管病高危人群颈动脉超声检测异常率为52.4%,略低于在全国6省市49 386名脑卒中高危人群中进行的多中心超声筛查所显示的56%[14]。此外也低于Wang等[15]在脑卒中筛查与防治工程项目中选取的城乡高危人群颈动脉异常率的63.7%。颈动脉内膜中层由平滑肌细胞(中层,80%)和内皮(内膜,20%)组成,目前的超声检测技术尚且无法将二者区分开来。除内膜增厚外,cIMT的增加还表示平滑肌肥大或增生,这可能与高血压或老龄化引起的硬化有关[16]。本研究发现,高龄、高血压、SBP与cIMT的增加相关的动脉硬化有关。LDL-C/HDL-C的升高同时增加发生颈动脉异常、斑块和CB的风险。有研究表明,与LDL-C或HDL-C作为独立的预测因子相比,LDL-C/HDL-C可以更好地对cIMT和CP进行预测[17-19],且相对于单一的血脂指标,LDL-C/HDL-C是CVD风险预测的重要指标之一,更具有临床检测指导价值。

CP是AS的局部表现,主要特征为cIMT增厚,且很可能与炎症、氧化、内皮功能障碍和平滑细胞增殖有关[20]。Mi等[21]的研究表明,年龄、性别、城乡、文化程度、高血压、糖尿病、吸烟、超重等因素在脑卒中高危人群中对CP存在影响,与本研究结果一致。同时,有研究显示,高龄、男性、高血压、吸烟、HDL-C是增加斑块多发发生风险的相关因素[22]。根据Spence等[23]的研究,高龄、男性、高脂血症、高血压和吸烟等传统危险因素是CP面积的决定因素,占CP变异的60%左右。一般人群中,cIMT年变化的平均估计值为0.001~0.030 mm[24]。而CP在纵向研究中的增长速度是cIMT的2.4倍[25],这为在短时间内对疾病进展进行评估提供了可能。生物学上,cIMT仅是心血管病风险指标,而CP是AS的独特表型,而不是cIMT的简单延续,与cIMT相比能更好地预测心血管疾病[26-27]。法国一项3个城市研究显示,相对于传统危险因素,斑块是CVD的独立危险因素,随着斑块数量的增加,CVD患病风险显著增加[28]。

本研究显示,BMI的平均值在cIMT增厚组中最大,在颈动脉狭窄组中最小,这与Bian等[22]的研究结果一致。这提示BMI可能主要影响亚临床AS早期阶段,而发展阶段则更多是由高血压、糖尿病、血脂异常等因素相互作用产生影响。多因素分析中,BMI每增加1个标准差,斑块患病和斑块负担的风险分别降低5.2%和11.0%,这可能与患病知晓后改善生活方式有关。在老年慢性阻塞性肺疾病患者中也发现低BMI是颈动脉狭窄的独立危险因素,低BMI患者血管疾病往往更为严重[29]。同时,既往的研究也指出在冠状动脉疾病患者中,与超重和肥胖组相比,体重过轻和正常组的CP发生率较高,高BMI者生存率高于正常BMI者[30-31]。有研究表明,BMI与冠状动脉疾病、终末期肾病和中风等患者在心血管事件上呈现负相关关系,这被称为“肥胖悖论”[32-34]。Gao等[35]通过结构方程式分析得出,BMI通过控制血糖等其他危险因素对亚临床AS产生间接影响。亚临床AS患者年龄较大,更多出现血管老化和不同的主要结构和功能变化(cIMT增厚、动脉扩张和弹性壁特性随血管硬化而恶化),老年患者体重通常偏低,低BMI与低体重有关。腰围与颈动脉异常、斑块和斑块负担在多因素分析中均无独立联系,提示与腹型肥胖相比,全身脂肪含量可能对亚临床AS有更好的预测效果,但目前研究结果并不一致,有待进一步探讨。

综上所述,在江苏省心血管病高危人群中,与CP和斑块负担发生风险增加的相关因素有高龄、城市居民、高血压、吸烟、脉压差增大、LDL-C/HDL-C升高等。应针对这些危险因素对心血管病高危人群进行早期防控,倡导健康的生活方式,积极控烟并定期体检。采取有效的干预措施并开展宣传文化有利于减缓心血管疾病进展,降低其致残率和致死率,为江苏省心血管病防治工作提供方向。但由于本研究为横断面调查,颈动脉异常与心血管病之间的关联有待通过进一步随访加以完善。

利益冲突 所有作者均声明不存在利益冲突

志谢 感谢常州市、淮安市、徐州市贾汪区、苏州市常熟市、南通市海安市和连云港市东海县所有参与项目的工作人员对本调查工作的大力支持和帮助

| [1] |

陈伟伟, 高润霖, 刘力生, 等. 《中国心血管病报告2017》概要[J]. 中国循环杂志, 2018, 33(1): 1-8. Chen WW, Gao RL, Liu LS, et al. China cardiovascular disease report 2017[J]. Chin Circ J, 2018, 33(1): 1-8. |

| [2] |

Stary HC, Chandler AB, Dinsmore RE, et al. A definition of advanced types of atherosclerotic lesions and a histological classification of atherosclerosis. A report from the committee on vascular lesions of the council on arteriosclerosis, American heart association[J]. Circulation, 1995, 92(5): 1355-1374. DOI:10.1161/01.CIR.92.5.1355 |

| [3] |

Bis JC, Kavousi M, Franceschini N, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies from the CHARGE consortium identifies common variants associated with carotid intima media thickness and plaque[J]. Nat Genet, 2011, 43(10): 940-947. DOI:10.1038/ng.920 |

| [4] |

Zhang YQ, Bai LL, Shi M, et al. Features and risk factors of carotid atherosclerosis in a population with high stroke incidence in China[J]. Oncotarget, 2017, 8(34): 57477-57488. DOI:10.18632/oncotarget.15415 |

| [5] |

刘卫东, 王石雷, 冯晶军, 等. 山东省聊城地区卒中高危人群的筛查及颈动脉斑块分析[J]. 中华神经外科杂志, 2018, 34(10): 1056-1058. Liu WD, Wang SL, Feng JJ, et al. Screening of high-risk stroke patients and analysis of carotid plaque in Liaocheng area, Shandong province[J]. Chin J Neurosurg, 2018, 34(10): 1056-1058. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1001-2346.2018.10.020 |

| [6] |

World Health Organization. Prevention of cardiovascular disease:pocket guidelines for assessment and management of cardiovascular risk[R]. Geneva:WHO, 2007:12-22.

|

| [7] |

国际生命科学学会中国办事处中国肥胖问题工作组联合数据汇总分析协作组. 中国成人体质指数分类的推荐意见简介[J]. 中华预防医学杂志, 2001(5): 62-63. Joint Data Analysis Collaboration Group of WGOC. Introduction to the recommendation of Chinese adult body mass index classification[J]. Chin J Prev Med, 2001(5): 62-63. DOI:10.3760/j:issn:0253-9624.2001.05.019 |

| [8] |

中国高血压防治指南修订委员会. 中国高血压防治指南2010[J]. 中华心血管病杂志, 2011, 39(7): 579-616. Writing Group of 2010 Chinese Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension. 2010 Chinese guidelines for the management of hypertension[J]. Chin J Cardiol, 2011, 39(7): 579-616. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-3758.2011.07.002 |

| [9] |

WHO. Definition and diagnosis of diabetes mellitus and intermediate hyperglycaemia:report of a WHO/IDF consultation[M]. Geneva: WHO Document Production Services, 2006: 1-3.

|

| [10] |

中国成人血脂异常防治指南修订联合委员会. 中国成人血脂异常防治指南(2016年修订版)[J]. 中国循环杂志, 2016, 31(10): 937-950. Joint Committee for the Revision of the Guidelines for Prevention and Treatment of Dyslipidemia. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of dyslipidemia in Chinese adults (revised 2016)[J]. Chin Circ J, 2016, 31(10): 937-950. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1000-3614.2016.10.001 |

| [11] |

Howard G, Sharrett AR, Heiss G, et al. Carotid artery intimal-medial thickness distribution in general populations as evaluated by B-mode ultrasound. ARIC Investigators[J]. Stroke, 1993, 24(9): 1297-1304. DOI:10.1161/01.STR.24.9.1297 |

| [12] |

Touboul PJ, Hennerici MG, Meairs S, et al. Mannheim carotid intima-media thickness and plaque consensus (2004-2006-2011). An update on behalf of the advisory board of the 3rd, 4th and 5th watching the risk symposia, at the 13th, 15th and 20th European Stroke Conferences, Mannheim, Germany, 2004, Brussels, Belgium, 2006, and Hamburg, Germany, 2011[J]. Cerebrovasc Dis, 2012, 34(4): 290-296. DOI:10.1159/000343145 |

| [13] |

Fox AJ, Eliasziw M, Rothwell PM, et al. Identification, prognosis, and management of patients with carotid artery near occlusion[J]. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol, 2005, 26(8): 2086-2094. |

| [14] |

华扬, 陶昀璐, 李梅, 等. 多中心超声筛查中国卒中高危人群颈动脉粥样硬化性病变结果的初步分析[J]. 中国脑血管病杂志, 2014, 11(12): 617-623. Hua Y, Tao YL, Li M, et al. Multicenter ultrasound screening for the results of carotid atherosclerotic lesions in a Chinese population with high-risk of stroke:a preliminary analysis[J]. Chin J Cerebrovasc Dis, 2014, 11(12): 617-623. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1672-5921.2014.12.001 |

| [15] |

Wang CF, Lv GP, Zang DW. Risk factors of carotid plaque and carotid common artery intima-media thickening in a high-stroke-risk population[J]. Brain Behav, 2017, 7(11): e00847. DOI:10.1002/brb3.847 |

| [16] |

Finn AV, Kolodgie FD, Virmani R. Correlation between carotid intimal/medial thickness and atherosclerosis:a point of view from pathology[J]. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 2010, 30(2): 177-181. DOI:10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.173609 |

| [17] |

Enomoto M, Adachi H, Hirai Y, et al. LDL-C/HDL-C Ratio Predicts Carotid Intima-Media Thickness Progression Better Than HDL-C or LDL-C Alone[J]. J Lipids, 2011, 2011: 549137. DOI:10.1155/2011/549137 |

| [18] |

Tamada M, Makita S, Abiko A, et al. Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio as a useful marker for early-stage carotid atherosclerosis[J]. Metabolism, 2010, 59(5): 653-657. DOI:10.1016/j.metabol.2009.09.009 |

| [19] |

Natarajan S, Glick H, Criqui M, et al. Cholesterol measures to identify and treat individuals at risk for coronary heart disease[J]. Am J Prev Med, 2003, 25(1): 50-57. DOI:10.1016/S0749-3797(03)00092-8 |

| [20] |

Mathiesen EB, Johnsen SH. Ultrasonographic measurements of subclinical carotid atherosclerosis in prediction of ischemic stroke[J]. Acta Neurol Scand Suppl, 2009, 120(s189): 68-72. DOI:10.1111/j.1600-0404.2009.01210.x |

| [21] |

Mi T, Sun SW, Zhang GQ, et al. Relationship between dyslipidemia and carotid plaques in a high-stroke-risk population in Shandong province, China[J]. Brain Behav, 2016, 6(6): e00473. DOI:10.1002/brb3.473 |

| [22] |

Bian LD, Xia LL, Wang YX, et al. Risk factors of subclinical atherosclerosis and plaque burden in high risk individuals:results from a community-based study[J]. Front Physiol, 2018, 9: 739. DOI:10.3389/fphys.2018.00739 |

| [23] |

Spence JD, Barnett PA, Bulman DE, et al. An approach to ascertain probands with a non-traditional risk factor for carotid atherosclerosis[J]. Atherosclerosis, 1999, 144(2): 429-434. DOI:10.1016/S0021-9150(99)00003-9 |

| [24] |

Lorenz MW, Polak JF, Kavousi M, et al. Carotid intima-media thickness progression to predict cardiovascular events in the general population (the PROG-IMT collaborative project):a Meta-analysis of individual participant data[J]. Lancet, 2012, 379(9831): 2053-2062. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60441-3 |

| [25] |

Spence JD, Hackam DG. Treating arteries instead of risk factors:a paradigm change in management of atherosclerosis[J]. Stroke, 2010, 41(6): 1193-1199. DOI:10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.577973 |

| [26] |

Spence JD, Hegele RA. Noninvasive phenotypes of atherosclerosis:similar windows but different views[J]. Stroke, 2004, 35(3): 649-653. DOI:10.1161/01.STR.0000116103.19029.DB |

| [27] |

Lorenz MW, Markus HS, Bots ML, et al. Prediction of clinical cardiovascular events with carotid intima-media thickness:a systematic review and Meta-analysis[J]. Circulation, 2007, 115(4): 459-467. DOI:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.628875 |

| [28] |

Plichart M, Celermajer DS, Zureik M, et al. Carotid intima-media thickness in plaque-free site, carotid plaques and coronary heart disease risk prediction in older adults. The three-city study[J]. Atherosclerosis, 2011, 219(2): 917-924. DOI:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.09.024 |

| [29] |

郭璐, 宫帅, 刘跃建, 等. 老年慢性阻塞性肺疾病患者动脉粥样硬化伴狭窄的高危因素分析[J]. 中国呼吸与危重监护杂志, 2016, 15(3): 236-240. Guo L, Gong S, Liu YJ, et al. Analysis of risk factors for carotid atherosclerotic stenosis in senior chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients[J]. Chin J Respir Crit Care Med, 2016, 15(3): 236-240. |

| [30] |

Park HW, Kim KH, Song IG, et al. Body mass index, carotid plaque, and clinical outcomes in patients with coronary artery disease[J]. Coron Artery Dis, 2017, 28(4): 278-286. DOI:10.1097/MCA.0000000000000467 |

| [31] |

Galal W, van Domburg RT, Feringa HHH, et al. Relation of body mass index to outcome in patients with known or suspected coronary artery disease[J]. Am J Cardiol, 2007, 99(11): 1485-1490. DOI:10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.01.018 |

| [32] |

Angerås O, Albertsson P, Karason K, et al. Evidence for obesity paradox in patients with acute coronary syndromes:a report from the Swedish Coronary Angiography and Angioplasty Registry[J]. Eur Heart J, 2013, 34(5): 345-353. DOI:10.1093/eurheartj/ehs217 |

| [33] |

Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kopple JD. Obesity paradox in patients on maintenance dialysis[J]. Contrib Nephrol, 2006, 151: 57-69. DOI:10.1159/000095319 |

| [34] |

Andersen KK, Olsen TS. The obesity paradox in stroke:lower mortality and lower risk of readmission for recurrent stroke in obese stroke patients[J]. Int J Stroke, 2015, 10(1): 99-104. DOI:10.1111/ijs.12016 |

| [35] |

Gao ZQ, Khoury PR, McCoy CE, et al. Adiposity has no direct effect on carotid intima-media thickness in adolescents and young adults:use of structural equation modeling to elucidate indirect & direct pathways[J]. Atherosclerosis, 2016, 246: 29-35. DOI:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2015.11.033 |

2019, Vol. 40

2019, Vol. 40