文章信息

- 国家免疫规划技术工作组流感疫苗工作组.

- National Immunization Advisory Committee(NIAC) Technical Working Group(TWG).

- 中国流感疫苗预防接种技术指南(2019-2020)

- Technical guidelines for seasonal influenza vaccination in China, 2019-2020

- 中华流行病学杂志, 2019, 40(11): 1333-1349

- Chinese Journal of Epidemiology, 2019, 40(11): 1333-1349

- http://dx.doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2019.11.002

-

文章历史

收稿日期: 2019-10-22

流感是流感病毒引起的对人类健康危害较重的呼吸道传染病,其抗原性易变,传播迅速,每年可引起季节性流行,在学校、托幼机构和养老院等人群聚集的场所可发生暴发疫情。全人群对流感普遍易感,孕妇、婴幼儿、老年人和慢性病患者等高危人群感染后受到的危害更为严重。接种流感疫苗是预防流感的最有效手段。2018年,中国CDC印发了《中国流感疫苗预防接种技术指南(2018-2019)》(2018年版指南)。一年来,新的研究证据在国内外发表,新的疫苗产品在我国上市。为更好的指导我国流感预防控制和疫苗应用工作,国家免疫规划技术工作组流感疫苗工作组综合国内外最新研究进展,在2018年版指南的基础上进行了更新和修订,形成了《中国流感疫苗预防接种技术指南(2019-2020)》。

本指南更新的内容主要包括:第一,增加了新的研究证据,尤其是我国的研究结果,包括流感疾病负担、疫苗效果、疫苗安全性监测、疫苗预防接种成本效果等;第二,增加了一年来国家卫生健康委员会流感防控有关政策和措施;第三,更新了我国2019-2020年度国内批准上市及批签发的流感疫苗种类;第四,更新了本年度三价灭活流感疫苗(IIV3)和四价灭活流感疫苗(IIV4)组份。

一、病原学基础、临床特点和实验室诊断流感病毒属于正粘病毒科,是单股、负链、分节段的RNA病毒。根据病毒核蛋白和基质蛋白,分为甲、乙、丙、丁(或A、B、C、D)4型。甲型流感病毒根据病毒表面的血凝素(Hemagglutinin,HA)和神经氨酸酶(Neuraminidase,NA)的蛋白结构和基因特性,可分为多种亚型,目前已发现18个HA(H1~18)和11个NA(N1~11)亚型[1]。甲型流感病毒除感染人外,在动物中广泛存在,如禽类、猪、马、海豹以及鲸鱼和水貂等。乙型流感分为Victoria系和Yamagata系,可在人群中循环,最近数据显示海豹也可被感染。丙型流感病毒感染人、狗和猪,仅导致上呼吸道感染的散发病例[2]。丁型流感病毒,主要感染猪、牛等,尚未发现感染人的病例[3-5]。目前引起流感季节性流行的病毒是甲型流感病毒H1N1、H3N2亚型及乙型流感病毒的Victoria和Yamagata系。

流感一般表现为急性起病、发热(部分病例可出现高热,达39~40 ℃),伴畏寒、寒战、头痛、肌肉和关节酸痛、极度乏力、食欲减退等全身症状,常有咽痛、咳嗽,可有鼻塞、流涕、胸骨后不适、颜面潮红、结膜轻度充血,也可有呕吐、腹泻等症状。轻症流感常与普通感冒表现相似,但其发热和全身症状更明显。重症病例可出现病毒性肺炎、继发细菌性肺炎、急性呼吸窘迫综合征、休克、弥漫性血管内凝血、心血管和神经系统等肺外表现及多种并发症[1, 6]。流感的症状是临床常规诊断和治疗的主要依据。但由于流感的症状、体征缺乏特异性,易与普通感冒和其他上呼吸道感染相混淆[7]。流感确诊有赖于实验室诊断,检测方法包括病毒核酸检测、病毒分离培养、抗原检测和血清学检测[8]。

二、流行病学1.传染源、传播方式及潜伏期:流感患者和隐性感染者是季节性流感的主要传染源,主要通过其呼吸道分泌物的飞沫传播,也可以通过口腔、鼻腔、眼睛等黏膜直接或间接接触传播[1, 9]。常见潜伏期为1~4 d(平均2 d),从潜伏期末到发病的急性期都有传染性。一般感染者在临床症状出现前24~48 h即可排出病毒,排毒量在感染后0.5~1 d显著增加,在发病后24 h内达到高峰[10]。成年人和较大年龄儿童一般持续排毒3~8 d(平均5 d),患者感染不同毒株的排毒时间也会有差异。住院成年人患者可在发病后持续一周或更长的时间排毒,排毒量也更大[2]。低龄儿童发病时的排毒量与成年人相同,但排毒量下降更慢,排毒时间更长[11]。与成年人相比,婴幼儿病例中,长期排毒很常见(1~3周)。老年人和HIV感染者等免疫功能低下或缺陷人群的病毒清除能力更差,排毒时间更长[10, 12]。

2.流行特点和季节性:流感在温带地区表现为每年冬、春季的季节性流行和高发[13-15]。热带地区尤其在亚洲,流感的季节性呈高度多样化,既有半年或全年周期性流行,也有全年循环[14-17]。

2013年,一项针对我国不同区域流感季节性的研究显示[18],我国甲型流感的年度周期性随纬度增加而增强,且呈多样化的空间模式和季节性特征:北纬33°以北的北方省份,呈冬季流行模式,每年1-2月份出现单一年度高峰;北纬27°以南的省份,每年4-6月份出现单一年度高峰;两者之间的中纬度地区,每年1-2月份和6-8月份出现双周期高峰。而乙型流感在我国大部分地区呈单一冬季高发。2018年一项研究对我国2005-2016年度乙型流感流行特征进行了系统分析[19],总体而言,我国乙型流感的流行强度低于甲型;但在部分地区和部分年份,乙型流感的流行强度高于甲型,且乙型Yamagata系和Victoria系交替占优,以冬、春季流行为主,不同系的流行强度在各年间存在差异。

3.疾病负担:

(1)健康负担:

① 全人群:全人群对流感普遍易感。根据一项对全球32个流感疫苗接种随机对照队列中未接种疫苗人群的流感罹患率统计结果,有症状流感在成年人中的罹患率为4.4%(95%CI:3.0%~6.3%),>65岁人群为7.2%(95%CI:4.3%~12.0%);所有流感(包括无症状感染)在成年人中的罹患率为10.7%(95%CI:4.5%~23.2%)[20]。全球1970-2009年19个流行季未接种流感疫苗的成年人流感罹患率为3.5%(95%CI:2.3%~4.6%)[21]。北京市基于流感样病例(influenza like illness,ILI)和住院严重急性呼吸道感染病例(severe acute respiratory infection,SARI)监测的研究提示[22],2017-2018季节,北京市流感感染人数约为227.1万人,总感染率为10.5%,有症状发病率为6.9%;其中15~24岁组感染率和发病率分别为13.4%和8.8%,25~59岁组分别为6.4%和4.2%,≥60岁组为5.6%和3.7%。北京市针对2016-2018年流感住院病例的研究显示,流感住院患者病死率为0.5%[23]。流感在全球每年可导致29万~65万呼吸道疾病相关死亡[24]。最近基于全国流感监测和死因监测系统数据,采用模型方法估计了流感相关超额呼吸系统疾病死亡[25],结果显示,2010-2011至2014-2015季节,全国平均每年有8.8(95%CI:8.4~9.2)万例流感相关呼吸系统疾病超额死亡,占呼吸系统疾病死亡的8.2%(95%CI:7.8%~9.6%);全年龄组的超额死亡率平均为6.5(95%CI:6.3~6.8)/10万人年,年龄标化率为5.9(95%CI:5.5~6.3)/10万人年;≥60岁老年人的流感相关超额死亡人数占全人群的80%,其超额死亡率显著高于<60岁人群(38.5 /10万人年vs.1.5/10万人年)。对中国流感相关死亡负担研究的系统综述提示[26],老年人流感相关呼吸及循环系统疾病超额死亡率为30.8/10万~170.2/10万;非老年组为0.32/10万~2.6/10万;不同季节、不同病毒亚型导致的死亡也存在差异。

② 慢性基础性疾病患者:与同龄健康成年人相比,慢性基础性疾病患者感染流感病毒后,更易出现严重疾病或死亡,其流感相关住院率和超额死亡率更高。近期基于全球流感住院监测网络数据的分析发现,2013-2014北半球流感季,40%的流感相关住院病例患有慢性基础性疾病;对于大多慢性基础性疾病而言,甲型H3N2、H1N1亚型和乙型Yamagata系所致重症流感的风险无显著差异[27]。我国2011-2013年住院SARI病例哨点监测数据显示,37%的重症流感病例患有慢性基础性疾病,其中心血管疾病(21.5%)、慢性阻塞性肺疾病(chronic obstructive pulmonary disease,COPD)(7.7%)和糖尿病(7.4%)最为常见[28]。澳大利亚一项对患有慢性肺部疾病(chronic lung diseases,CLD)儿童开展的10年队列研究提示[29],CLD患儿和非CLD儿童流感相关住院率分别为3.9(95%CI:2.6~5.2)和0.7(95%CI:0.5~0.9)/1 000人年。与健康人群相比,慢性基础性疾病患者流感相关死亡率明显增高。一项综述性研究发现,流感流行季节COPD患者甲型流感相关超额病死率超过30%,明显高于健康人群(≤0.1%)[30]。

③ 孕妇:流感对孕妇的健康危害比较严重。孕妇怀孕后由于机体免疫和生理上的变化,感染流感病毒后容易出现呼吸系统、心血管系统和其他器官的并发症[31]。日本研究表明,2010-2011至2013-2014四个流感季中,孕妇比未怀孕的育龄妇女更容易发生呼吸系统疾病相关的住院(RR=4.3,95%CI:1.96~9.41)[32]。美国一项1998-2005年孕妇流感死亡负担研究显示,孕晚期孕妇流感相关死亡率最高,约为3.1/100万活产[33]。西班牙的回顾性队列研究纳入了约20万孕妇,结果表明孕晚期因流感住院风险显著增加(RR=1.9,95%CI:1.0~3.4)[34]。我国关于2009年大流行期间甲型H1N1 pdm09住院病例的研究发现,孕妇仅占育龄妇女人口数的3%,但20%的甲型H1N1 pdm09死亡病例为孕妇,其中仅7%患有慢性基础性疾病;与未怀孕的健康育龄妇女相比,孕妇出现严重疾病的风险增加至3.3倍(95%CI:2.7~4.0),孕中期(OR=6.1)和孕晚期(OR=7.6)出现严重疾病的风险进一步增加[35]。研究还显示,孕妇患流感可对胎儿和新生儿产生影响,出现死产、婴儿死亡、早产和出生低体重等[36-38]。

④ 儿童:每年流感流行季节,儿童流感罹患率约为20%~30%;在某些高流行季节[39],儿童流感年感染率可达50%左右[40-41]。关于流感罹患率(包括有症状和无症状的感染)的综述研究提示[20],<18岁儿童流感罹患率约为22.5%(95%CI:9.0%~46.0%),而成年人流感罹患率约为10.7%(95%CI:4.5%~23.2%)。北京市2017-2018季节流感感染率和发病率研究提示,0~4岁组和5~14岁组发病率最高,分别为33.0%(95%CI:26.4%~43.1%)和21.7%(95%CI:17.4%~28.4%)[22]。苏州市2011-2017季节<5岁儿童确诊流感导致的ILI就诊率为6.4/100人年,其中2011-2012季节最高(20.5/100人年),2012-2013季节最低(2.4/100人年)[42]。<5岁儿童感染流感后出现重症的风险较高。湖北省荆州市基于人群的研究表明,69%的流感导致SARI住院患者为<5岁儿童,该年龄组流感相关SARI住院率达2 021/10万人年~2 349/10万人年,其中6~11月龄婴儿住院率最高(360/10万人年~3 805 /10万人年)[43]。儿童感染流感可导致死亡,患基础性疾病的儿童的死亡风险显著高于健康儿童,但也有将近半数的死亡病例发生在健康儿童中[39]。对全球流感相关死亡的模型研究估计,纳入的92个国家每年约有9 243~105 690名<5岁儿童死于流感相关呼吸道疾病[24]。

⑤ 学生:学校作为封闭的人群密集场所,更容易造成流感病毒的传播[44-45]。我国每年报告的流感暴发疫情中,>90%发生在学校和托幼机构。与其他人群相比,学龄儿童的流感感染率最高[46]。经估算,北京市2015-2016季节5~14岁儿童流感感染率为18.7%(95%CI:12.9%~24.5%),明显高于青壮年和老年人群[47]。学龄儿童在学校、家庭和社区的流感传播中发挥重要的作用,流感流行可引起大量学龄儿童缺课和父母缺勤[48-49]。

⑥ 医务人员:医务人员在日常诊疗活动中接触流感患者的机会较多,因而感染流感病毒的风险高于普通人群。对1957-2009年全球29项研究的Meta分析显示,未接种流感疫苗的医务人员每季节实验室确诊的流感发病率为18.7%(95%CI:15.8%~22.1%),是健康成年人的3.4倍(95%CI:1.2~5.7)[50]。中国香港地区在2009年甲型H1N1流行期间,2.6%的医务人员确诊感染,其中护理人员占53.4%[51]。2016年的系统综述显示,与普通人群相比,医务人员在甲型H1N1流行期间感染风险更高(OR=2.08,95%CI:1.73~2.51)[52]。医务人员感染流感病毒可增加院内感染的风险。研究显示,在感染流感病毒的医务人员中,35%为无症状感染[53],>75%的医务人员出现流感样症状后仍继续工作[54-55]。

⑦ 老年人:感染流感是老年人的重要死因。关于全球流感超额死亡率的模型研究表明,<65岁组中因流感相关呼吸道超额死亡率为0.1/10万~6.4/10万,65~74岁组中超额死亡率为2.9/10万~44.0/10万,>75岁组为17.9/10万~223.5/10万[24]。2017-2018季节(以乙型流感为主)欧洲的超额死亡研究提示,≥65岁老年人流感相关全死因超额死亡率为154.1(95%CI:149.4~158.9)/10万,与甲型H3N2亚型为优势毒株的2016-2017季节类似,提示乙型流感疾病负担不容小觑[56]。我国流感超额死亡研究显示,≥65岁老年人流感相关的呼吸和循环系统疾病、全死因超额死亡率分别为64/10万~147/10万、75/10万~186/10万[57-59],与新加坡[58, 60]、葡萄牙[61]、美国[62]等国家接近。与其他年龄组相比,流感相关死亡风险在老年人最高。≥65岁老年人流感相关超额死亡率远高于0~64岁组,80%~95%的流感相关超额死亡发生在≥65岁老年人[25, 57-59, 63]。流感也可导致老年人出现相当高的住院负担。2010-2012年湖北省荆州市基于人群的研究发现,≥65岁老年人中确诊流感导致的SARI病例住院率为89/10万~141/10万[64]。此外,养老院、疗养院等老年人集体居住的机构容易出现流感暴发疫情。

(2)经济负担和健康效用:研究显示,我国流感门诊病例的直接医疗成本为156~595元/人,间接成本为198~366元/人[49, 65-67]。流感住院病例的经济负担约为门诊病例的10倍。2018年苏州地区对儿童流感门诊病例的研究显示[68],流感阳性病例的门急诊就诊平均总费用高于阴性病例(768.0元vs. 688.4元)。另外,流感感染还可明显影响患者的生命质量,>60%的流感门诊和住院病例报告具有疼痛、不适和焦虑、沮丧。患流感期间,门诊和住院病例的健康效用值(health utility)分别为0.61和0.59,损失的质量调整生命天(quality adjusted life days,QALD)为1.62和3.51 d[69]。2013年我国研究显示,患者有慢性基础性疾病的流感患者其门诊和住院费均高于无基础性疾病的流感患者(门诊:186美元vs. 146美元;住院:1 800美元vs. 1 189美元)[66],对于生存质量的研究也显示,基础性疾病患者的健康相关生存质量显著低于无基础性疾病者[69]。流感同样会造成年人群生产力的下降,如工作缺勤。中国香港地区针对医务工作者的回顾性队列研究显示,2005年未接种流感疫苗的医务人员平均每人因ILI而缺勤1.75 d[70]。苏州地区一项研究显示,儿童流感病例的缺课天数和家长缺勤天数分别为1.3和1.4 d[68]。

4.流感的预防治疗措施:每年接种流感疫苗是预防流感最有效的手段,可以显著降低接种者罹患流感和发生严重并发症的风险。奥司他韦、扎那米韦、帕拉米韦等神经氨酸酶抑制剂是甲型和乙型流感的有效治疗药物。病程早期尤其是发病48 h之内应用抗流感病毒药物能显著降低流感重症和死亡的发生率。抗病毒药物应在医生的指导下使用。药物预防不能代替疫苗接种,只能作为没有接种疫苗或接种疫苗后尚未获得免疫能力的重症流感高危人群的紧急临时预防措施,可使用奥司他韦、扎那米韦等。采取日常防护措施也可以有效减少流感的感染和传播,包括保持良好的呼吸道卫生习惯,咳嗽或打喷嚏时,用纸巾、毛巾等遮住口鼻;勤洗手,尽量避免触摸眼睛、鼻或口;均衡饮食,适量运动,充足休息等。避免近距离接触流感样症状患者,流感流行季节,尽量避免去人群聚集场所;出现流感样症状后,患者应居家隔离观察,不带病上班、上课,接触家庭成员时戴口罩,减少疾病传播;流感样症状患者去医院就诊时,患者及陪护人员要戴口罩,避免交叉感染。

三、流感疫苗1.国内外上市的流感疫苗:全球已上市的流感疫苗分为流感灭活疫苗(inactivated influenza vaccine,IIV)和流感减毒活疫苗(live attenuated influenza vaccine,LAIV)。按照疫苗所含组份,分为三价和四价流感疫苗,三价疫苗组份含有甲型H3N2、H1N1亚型和乙型毒株的1个系,四价疫苗组份含甲型H3N2、H1N1亚型和乙型Victoria系、Yamagata系。根据生产工艺,又可分为基于鸡胚、基于细胞培养和重组流感疫苗(recombinant influenza vaccines,RIV)。国外还上市了针对特定人群的高抗原含量IIV、佐剂疫苗以及皮内接种疫苗等。我国现已批准上市的流感疫苗有IIV3和IIV4,IIV3包括裂解疫苗和亚单位疫苗,IIV4为裂解疫苗。根据国家药监局网站和疫苗批签发信息,2019-2020季节有7家厂家供应流感疫苗。此外,一种鼻喷三价LAIV在上市审批过程中,适用人群为3~17岁,每剂0.2 ml。本季节供应流感疫苗的厂家及其产品信息见表 1。

2. IIV3和IIV4接种后的免疫反应、免疫持久性:欧盟药品评价局和美国食品药品管理局的标准要求流感疫苗接种后:①血凝素抑制(hemagglutination inhibition,HI)抗体≥1:40;②血清阳转率,即免疫接种前HI抗体<1:10,免疫后HI抗体≥1:40,或免疫接种前HI抗体≥1:10,免疫接种后HI抗体几何平均滴度(geometric mean titers,GMT)增长≥4倍。人体对感染流感病毒或接种流感疫苗后获得的免疫力会随时间衰减,衰减程度与人的年龄和身体状况、疫苗抗原等因素有关,临床试验的证据提示,接种IIV对抗原类似毒株的保护作用可维持6~8个月[71]。接种1年后血清抗体水平显著降低,但部分毒株的保护作用持续时间可更长。为匹配不断变异的流感病毒,WHO在多数季节推荐的流感疫苗组份会更新≥1个毒株,疫苗毒株与前一季节完全相同的情况也存在。为保证接种人群得到最大程度的保护,即使流感疫苗组份与前一季节完全相同,鉴于多数接种者抗体滴度已显著下降[72-74],因此不管前一季节是否接种流感疫苗,仍建议在当年流感季节来临前接种。目前,我国供应2种IIV4。根据2种疫苗上市前的临床试验结果,其接种后甲型H3N2、H1N1亚型和乙型Yamagata、Victoria系的HI抗体阳转率、HI抗体GMT平均增长倍数和血清抗体保护率均达到标准,提示该疫苗具有较好的免疫原性。

3. IIV3和IIV4的免疫原性、效力和效果:免疫原性是指抗原能够刺激机体形成特异抗体或致敏淋巴细胞的能力,评价指标主要为病毒株特异性HI抗体水平和血清抗体阳转率,评价结果会受接种者年龄、免疫功能和接种前抗体水平的影响。疫苗的效力通常是指其在上市前随机对照试验(randomized controlled trial,RCT)中理想条件下的有效性;疫苗的效果则指其在人群中实际应用的有效性。评价流感疫苗效力和效果的结局指标主要包括血清抗体水平和阳转率、实验室确诊流感、急性呼吸道疾病或ILI就诊、流感和肺炎相关住院或死亡等。流感疫苗需要每年接种。疫苗效果研究证实了重复接种的必要性。据中国香港地区对2012-2017连续5个流感季节儿童住院病例中流感疫苗效果的分析估计[75],流感疫苗接种后每个月效果约下降2%~5%,接种后0.5~2个月时疫苗效果估计为79%(95%CI:64%~88%),至接种后7~9个月时疫苗效果仅余45%(95%CI:22%~61%)。此外,一项系统综述比较了连续2个季节接种、仅本季节接种、仅上一季节接种和2个季节均未接种的流感疫苗效果[76],提示无论上一季节接种状态如何,本季节都应重新接种流感疫苗。

(1)全人群:IIV在健康成年人中免疫原性良好。在健康成年人中,据随机对照试验的系统综述估计,IIV约可预防59%(95%CI:51%~66%)的实验室确诊流感[77-78];当疫苗株和循环株匹配时,接种IIV可减少42%(95%CI:9%~63%)的ILI就诊[78]。一项系统综述纳入了1998-2008年国内文献中的2项RCT和11项队列研究[79],显示流感疫苗对我国18~59岁成年人ILI的预防效果为47%(95%CI:25%~63%)。在全年龄组人群中,检测阴性病例对照研究的系统综述(包含2004-2015年的56项研究)发现流感疫苗对不同型别和亚型的流感的预防效果有明显差异,其中乙型为54%(95%CI:46%~61%),甲型H1N1 pdm09亚型(2009年及以后)为61%(95%CI:57%~65%),H1N1亚型(2009年之前)为67%(95%CI:29%~85%),H3N2亚型为33%(95%CI:26%~39%)[80]。国外RCT试验的Meta分析显示,在≥18岁成年人中,IIV4与IIV3在相同疫苗株的血清保护率和抗体阳转率方面无显著性差异,IIV4中增加的乙型流感系的抗体保护率和抗体阳转率明显高于IIV3[81-82]。

(2)孕妇:妊娠期接种流感疫苗,既可保护孕妇,降低孕期患流感、孕期发热、子痫前期、胎盘早破的风险,也可通过胎传抗体保护6月龄内无法接种流感疫苗的新生儿免于罹患流感[83]。在4项RCT和3项观察性研究的Meta分析中,孕期接种流感疫苗对<6月龄婴儿实验室确诊的流感的保护率为48%(95%CI:33%~59%);在4项观察性研究的Meta分析中,孕期接种流感疫苗对<6月龄婴儿实验室确诊的流感相关住院的保护率为72%(95%CI:39%~87%)[84]。2019年的Meta分析指出[85],相较于孕早期接种流感疫苗,孕晚期接种流感疫苗的孕妇及其新生儿体内HI滴度上升倍数更高,且孕晚期接种流感疫苗更有利于抗体传递给胎儿。

(3)儿童:>6月龄儿童按推荐的免疫程序接种IIV3后对流感病毒感染有保护作用。2012年一项IIV3效力和效果的Meta分析显示[77],6~23月龄儿童的疫苗效果为40%(95%CI:6%~61%),24~59月龄儿童为60%(95%CI:30%~78%)。国内研究显示,2011-2012年度IIV3对36~59月龄及6~35月龄的保护效果分别为58.2%和49.5%[86]。国外研究提示,<9岁儿童首次接种IIV3时,接种2剂次比1剂次能提供更好的保护作用,如5~8岁儿童接种2剂IIV3后,针对甲型H1N1、H3N2和乙型流感病毒产生的抗体滴度显著高于接种1剂次[87]。日本对2013-2018年度6月龄至12岁儿童的研究提示:无论接种1剂次还是2剂次IIV,均对儿童感染流感具有保护效果,但接种2剂次疫苗在部分年度对乙型流感的保护效果更好[88]。中国香港地区对2011-2019年度因急性呼吸道感染住院的6月龄至9岁儿童开展了接种2剂次和1剂次流感疫苗效果研究[89],发现首次接种流感疫苗完成2剂次程序和仅接种1剂次对流感确诊住院病例的保护效果分别为73%(95%CI:69%~77%)和31%(95%CI:8%~48%)。因此,低龄儿童首次接种流感疫苗应接种2剂,才能获得最大程度的保护。

研究提示,IIV4对乙型流感的免疫原性优于IIV3。2013-2014季节在欧洲几国的3~8岁儿童开展的随机、双盲、接种IIV3为对照的临床试验提示,接种IIV4后对IIV3未含的乙型流感产生的GMT高于IIV3诱导产生,即IIV4具有更好的免疫原性[90]。中国香港地区2017-2018季节一项6月龄至17岁儿童流感疫苗效果研究[91],共纳入1 078名儿童,研究对象接种的大多为IIV4,结果显示流感疫苗对确诊流感住院总的保护效果为65.6%(95%CI:42.7%~79.3%),对甲型和乙型流感的保护效果分别为66.0%(95%CI:3.4%~88.0%)和65.3%(95%CI:39.5%~80.1%)。北京市对2013-2016季节流感疫苗效果模型研究发现,对于5~14岁儿童,3个季节接种流感疫苗分别可以减少约104 000(95%CI:101 000~106 000)例、23 000(95%CI:22 000~23 000)例和21 000(95%CI:21 000~22 000)例流感相关门/急诊病例就诊[92]。2016-2017季节北京市流感疫苗对减少流感相关门/急诊就诊效果为25%(95%CI:0%~43%),对甲型H1N1 pdm09为中等保护效果,而对甲型H3N2为低保护效果[93]。

(4)学生:开展基于学校的流感疫苗接种可有效减少学龄儿童流感感染的发生。2014-2015季节,北京市基于中小学校流感集中发热疫情的研究表明,在流感病毒疫苗株与流行株不匹配的情况下,学生接种流感疫苗的保护效果为38%(95%CI:12%~57%)[94];在确诊流感的学生中,接种流感疫苗的学生与未接种的学生相比,出现>38 ℃发热的风险显著减低(OR=0.42,95%CI:0.19~0.93)[95]。疫苗株与流行毒株匹配的季节,北京市流感疫苗大规模集中接种可使流感集中发热疫情的发生风险大幅降低(OR=0.111,95%CI:0.075~0.165)[96]。

(5)老年人:2018年一篇对8个随机对照试验的Meta分析发现,老年人接种流感疫苗预防流感的保护效力为58%(95%CI:34%~73%)[97]。2015-2016、2016-2017和2017-2018季节,美国≥65岁老年人接种流感疫苗预防因流感导致的急性呼吸道疾病就诊的效果分别为42%(95%CI:6%~64%)、46%(95%CI:4%~70%)和18%(95%CI:-25%~47%)[98-100]。2017年针对检测阴性病例对照研究中社区老年人个体水平数据的Meta分析发现,无论流感疫苗与流行株是否匹配,接种流感疫苗均有效[匹配时保护效果为44.4%(95%CI:22.6%~60.0%);不匹配时保护效果为20.0%(95%CI:3.5%~33.7%)][101]。对1998-2008年我国流感疫苗效果研究的Meta分析发现,流感疫苗对≥60岁老年人的流感样疾病的预防效果为53%(95%CI:20%~72%)[79]。接种流感疫苗还可降低老年人流感相关并发症发生率,减少流感相关住院及死亡。2013年的Meta分析发现,在流感季节,老年人接种流感疫苗能预防28%(95%CI:26%~30%)的流感相关致命性或非致命性并发症、39%(95%CI:35%~43%)的流感样症状、49%(95%CI:33%~62%)的确诊流感[102]。

(6)慢性基础性疾病患者:我国开展的队列研究表明,接种IIV3可以减少COPD和慢性支气管炎的急性感染和住院[103-104]。成都地区一项队列研究发现,与未接种疫苗的对照组相比,IIV3接种3、6个月后COPD急性加重的住院天数分别减少3.3、7.1 d[103]。流感疫苗对儿童和成年人哮喘患者有较好免疫原性[105],哮喘患者接种流感疫苗能够有效减少流感感染和哮喘发作[106]。流感疫苗在心血管疾病患者中免疫原性良好,能够保护心血管病患减少流感感染。冠心病患者接种流感疫苗后,可以减少急性冠脉综合征(acute coronary syndromes,ACS)患者的心血管不良事件发生率,降低其住院风险和与心脏病相关的死亡率[107],减少ACS患者与流感有关的直接和间接医疗成本[108-109]。糖尿病患者接种流感疫苗1个月后,血清转换率和保护率均达到标准;流感疫苗的免疫原性主要与年龄和既往抗体水平滴度有关,而与是否患糖尿病无关[110]。18~64岁的糖尿病患者接种流感疫苗对住院的保护效果是58%;老年人糖尿病患者接种流感疫苗,对住院的保护效果为23%,对全死因死亡的保护效果为38%~56%[111]。另外,接种流感疫苗可以减少免疫功能受损的流感住院儿童并发症的发生风险,缩短住院时间[112]。

(7)医务人员:医护人员接种流感疫苗可保护自身健康。与流感病毒匹配良好的季节性流感疫苗在医务人员中的疫苗效力可达90%[113-114]。一项纳入了1980-2018年研究结果的系统综述显示,疫苗接种组实验室确诊的流感发病率明显低于未接种组(合并RR=0.40,95%CI:0.23~0.69),并且ILI导致的缺勤率降低(合并RR=0.62,95%CI:0.45~0.85)[115]。另一项系统综述显示,医护人员接种流感疫苗可以减少42%的临床诊断流感,同时减少29%的全病因死亡[113, 116]。我国研究也发现[117-118],医务人员接种流感疫苗可以减少缺勤、ILI和呼吸系统疾病的发生和就诊,降低心脑血管疾病和糖尿病的就诊率。此外,接种流感疫苗还可作为保障医务人员职业健康、院内感染控制的措施,并维持医疗系统正常运转。

4. IIV3和IIV4的安全性:接种流感疫苗是安全的,但也可能会出现不良反应。流感疫苗常见的副作用主要表现为局部反应(接种部位红晕、肿胀、硬结、疼痛、烧灼感等)和全身反应(发热、头痛、头晕、嗜睡、乏力、肌痛、周身不适、恶心、呕吐、腹痛、腹泻等)。通常是轻微的,并在几天内自行消失,极少出现重度反应。研究表明IIV3和IIV4在安全性上没有差别[119-127],国产和进口流感疫苗的安全性也差异无统计学意义[128-130]。

疑似预防接种异常反应(adverse event following immunization,AEFI)是指在预防接种后发生的怀疑与预防接种有关的不良反应或医学事件。我国于2010年发布《全国疑似预防接种异常反应监测方案》,要求责任报告单位和报告人发现属于报告范围的AEFI(包括接到受种者或其监护人的报告)后应当及时向受种者所在地的县级卫生行政部门、药品监督管理部门报告,相关信息将通过AEFI信息管理系统进行网络报告,AEFI监测属于被动监测。2015-2018年AEFI信息管理系统的监测数据分析显示,所有不良反应中报告最多的为发热(腋温≥37.1 ℃),其中高热(腋温≥38.6 ℃)发生率为4.274/10万剂,儿童型疫苗略高于成年人型(4.465/10万剂vs. 4.165/10万剂);非严重异常反应中,以过敏性皮疹(442例,0.531/10万剂)和血管性水肿(70例,0.084/10万剂)报告最多;严重异常反应的报告发生率低,为0.143/10万剂,排名前两位为热性惊厥(27例,0.032/10万剂)和过敏性紫癜(21例,0.025/10万剂)[131]。

5.疫苗成本效果、成本效益:接种流感疫苗能有效减少流感相关门/急诊、住院和死亡人数,继而降低治疗费用,产生明显的经济效益。总结全球51项流感疫苗接种卫生经济学评价结果的综述发现[132],其中22项研究(包括评估儿童、老年人和孕妇接种流感疫苗的成本效果)认为接种流感疫苗可节省成本,13项研究的成本效果<1万美元或成本效益比接近1(常用的成本效果评价标准:当成本效果比小于所在国家人均GDP时,认为干预措施极具有成本效果;当成本效果比为1~3倍人均GDP时,认为干预措施具有成本效果;当成本效果比>3倍人均GDP时,干预措施不具有成本效果),13项研究的成本效果为1万~5万美元或者成本效益比<6,3项研究的成本效果>5万美元,绝大部分研究认为儿童接种流感疫苗可节省成本或具有成本效果,在老年人和孕妇中接种流感疫苗具有较好的成本效果。另一项系统综述发现,从全社会的角度,对儿童、孕产妇、高危人群和医务人员开展流感疫苗接种具有成本效果[133]。

我国一项研究采用静态马尔科夫模型,基于我国医疗保健系统角度开展的评价老年人接种IIV3、IIV4及不接种流感疫苗成本效果的研究发现[134],接种IIV3和IIV4均比不接种流感疫苗给老年人带来更高的健康效用,且均具有良好成本效果。另一项采用构建决策树模型分析我国糖尿病患者免费接种流感疫苗成本效果的研究提示[135],当支付意愿阈值采用我国2016年人均GDP 53 680元时,为糖尿病患者提供免费流感疫苗接种具有成本效果的概率为99.1%。

四、2019-2020年度接种建议每年接种流感疫苗是预防流感最有效的措施。目前,流感疫苗在我国大多数地区属于第二类疫苗,既公民自费、自愿接种。国家卫生健康委员会2018年印发的《关于进一步加强流行性感冒防控工作的通知》(国卫疾控函〔2018〕254号)中明确了我国流感防控工作的指导原则是“预防为主、防治结合、依法科学和联防联控”,提出了“强化监测预警、免疫重点人群、规范疫情处置、落实医疗救治、广泛宣传动员”的防控策略。其中高危人群的疫苗预防接种是防控重点,首次针对医务人员疫苗接种提出了具体要求,医疗机构应该为医务人员免费接种,医务人员应该主动接种并达到高覆盖率。2019年7月,健康中国行动推进委员会制定印发了《健康中国行动(2019中国行动推年)》,列出了15项重大行动,包括全方位干预健康影响因素、维护全生命周期健康和防控重大疾病3个领域。其中在“慢性呼吸系统疾病防治行动”中建议慢性呼吸系统疾病患者和老年人等高危人群主动接种流感疫苗和肺炎球菌疫苗,在“传染病及地方病防控行动”中,明确提出儿童、老年人、慢性病患者的免疫力低、抵抗力弱,是流感的高危人群,建议每年流感流行季节前在医生指导下接种流感疫苗,并鼓励有条件地区为≥60岁老年人、托幼机构幼儿、在校中小学生和中等专业学校学生免费接种流感疫苗,同时要求保障流感疫苗供应。该行动计划为未来推进流感疫苗预防接种提供了指导意见和工作要求。

为提高公众对流感疾病特征、危害及疫苗预防作用的认识,逐步提高高危人群的疫苗覆盖率,各级CDC要积极组织开展科学普及、健康教育、风险沟通和疫苗政策推进活动,组织指导疫苗接种时,应重点把握好剂型选择、优先接种人群、接种程序、禁忌证和接种时机等技术环节。

1.抗原组份:WHO推荐的2019-2020年度北半球IIV3组份为甲型/Brisbane/02/2018(H1N1)pdm09类似株、甲型/Kansas/14/2017(H3N2)类似株和乙型/Colorado/06/2017(Victoria系)类似株。WHO推荐的IIV4组份包含乙型毒株的2个系,为上述3个毒株及乙型/Phuket/3073/2013(Yamagata系)类似株。与上一年度相比,更换了甲型H1N1和H3N2亚型病毒毒株。

2.疫苗种类及适用年龄组:目前,我国批准上市的流感疫苗包括IIV3和IIV4,其中IIV3有裂解疫苗和亚单位疫苗,可用于≥6月龄人群接种,包括0.25 ml和0.5 ml 2种剂型,0.25 ml剂型含每种组份血凝素7.5 μg,适用于6~35月龄婴幼儿;0.5 ml剂型含每种组份血凝素15 μg,适用于≥36月龄的人群;IIV4为裂解疫苗,适用于≥36月龄的人群,为0.5 ml剂型,含每种组份血凝素15 μg。对可接种不同类型、不同厂家疫苗产品的人群,可自愿接种任1种流感疫苗,无优先推荐。

3.建议优先接种人群:流感疫苗安全、有效。原则上,接种单位应为≥6月龄所有愿意接种疫苗且无禁忌证的人提供免疫服务。国内外大量流感疾病负担的科学证据表明,不同人群患流感后的临床严重程度和结局不同,借鉴WHO立场和其他国家多年的应用经验,结合我国国情,推荐以下人群为优先接种对象:

(1)6~23月龄的婴幼儿:患流感后出现重症的风险高,流感住院负担重,应优先接种流感疫苗。疫苗在该年龄组的效果高度依赖于疫苗株与循环毒株的匹配程度。

(2)2~5岁儿童:流感疾病负担也较高,但低于<2岁儿童。该年龄组儿童接种流感疫苗后,其免疫应答反应通常优于<2岁儿童。

(3)≥60岁老年人:患流感后死亡风险最高,是流感疫苗接种的重要目标人群。虽然较多证据表明,现有流感疫苗在老年人中的效果不如年轻成年人,但疫苗接种仍是目前保护老年人免于罹患流感的最有效手段。

(4)特定慢性病患者:心血管疾病(单纯高血压除外)、慢性呼吸系统疾病、肝肾功能不全、血液病、神经系统疾病、神经肌肉功能障碍、代谢性疾病(包括糖尿病)等慢性病患者、患有免疫抑制疾病或免疫功能低下者,患流感后出现重症的风险很高,应优先接种流感疫苗。

(5)医务人员:是流感疫苗接种的重要优先人群,不仅可保护医务人员自身,维持流感流行季节医疗服务的正常运转,同时可有效减少医务人员将病毒传给流感高危人群的机会。

(6)<6月龄婴儿的家庭成员和看护人员:由于现有流感疫苗不可以直接给<6月龄婴儿接种,该人群可通过母亲孕期接种和对婴儿的家庭成员和看护人员接种流感疫苗,以预防流感。

(7)孕妇或准备在流感季节怀孕的女性:国内外大量研究证实孕妇罹患流感后发生重症、死亡和不良妊娠结局的风险更高,国外对孕妇在孕期任何阶段接种流感疫苗的安全性证据充分,同时接种疫苗对预防孕妇罹患流感及通过胎传抗体保护<6月龄婴儿的效果明确。另外,《WHO流感疫苗立场文件(2012年版)》将孕妇列为第一优先接种人群。但由于国内缺乏孕妇接种流感疫苗的安全性评价数据,我国上市的部分流感疫苗产品说明书仍将孕妇列为禁忌证。为降低我国孕妇罹患流感及严重并发症风险,经审慎评估,本指南建议孕妇或准备在流感季节怀孕的女性接种流感疫苗,孕妇可在妊娠任何阶段接种。

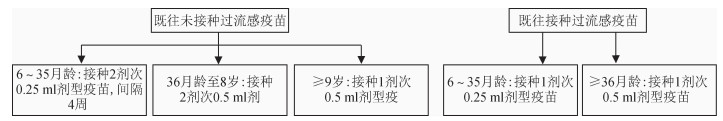

4.接种剂次:见图 1。

|

| 图 1 各年龄组流感疫苗接种剂次图示 |

(1)6月龄至8岁儿童:首次接种流感疫苗的6月龄至8岁儿童应接种2剂次,间隔≥4周;2018-2019年度或以前接种过≥1剂次流感疫苗的儿童,则建议接种1剂次。

(2)≥9岁儿童和成年人:仅需接种1剂。

5.接种时机:通常接种流感疫苗2~4周后,可产生具有保护水平的抗体,6~8月后抗体滴度开始衰减。我国各地每年流感活动高峰出现的时间和持续时间不同,为保证受种者在流感高发季节前获得免疫保护,建议各地在疫苗可及后尽快安排接种工作,最好在10月底前完成免疫接种;对10月底前未接种的对象,整个流行季节都可以提供免疫服务。同一流感流行季节,已按照接种程序完成全程接种的人员,无需重复接种。孕妇在孕期的任一阶段均可接种流感疫苗,建议只要本年度的流感疫苗开始供应,可尽早接种。

6.接种部位及方法:IIV的接种采用肌肉注射(皮内注射制剂除外)[6]。成年人和>1岁儿童首选上臂三角肌接种疫苗,6月龄至1岁婴幼儿的接种部位以大腿前外侧为最佳[6]。因为血小板减少症或其他出血性疾病患者在肌肉注射时可能发生出血危险,应采用皮下注射。

7.疫苗储存:按照《疫苗储存和运输管理规范(2017年版)》的要求,应在2~8 ℃避光保存和运输,严禁冻结。

8.禁忌证:对疫苗中所含任何成分(包括辅料、甲醛、裂解剂及抗生素)过敏者。患伴或不伴发热症状的轻中度急性疾病者,建议症状消退后再接种。上次接种流感疫苗后6周内出现格林巴利综合征,不是禁忌证,但应特别注意。《中华人民共和国药典(2015版)》未将对鸡蛋过敏者作为禁忌。药典规定流感疫苗中卵清蛋白含量应≤500 ng/ml,当前疫苗中的卵蛋白含量已大大低于国家标准。国外学者对于鸡蛋过敏者接种IIV或LAIV的研究也表明不会发生严重过敏反应[136-139],美国ACIP自2016年开始建议对鸡蛋过敏者亦可接种流感疫苗[140-141]。

9.药物相互作用:

(1)如正在或近期曾使用过任何其他疫苗或药物,包括非处方药,请于接种前告知接种医生。

(2)IIV与其他灭活及减毒活疫苗可同时在不同部位接种[141];未发现影响流感疫苗和联合接种疫苗的免疫原性和安全性的证据[142]。老年人可同时接种IIV和肺炎球菌疫苗[143-148]。

(3)免疫抑制剂(如皮质类激素、细胞毒性药物或放射治疗)的使用可能影响接种后的免疫效果[149-150]。为避免可能的药物间相互作用,任何正在进行的治疗均应咨询医生。

(4)服用流感抗病毒药物预防和治疗期间可以接种流感疫苗[141]。

10.接种注意事项:各接种单位要按照《预防接种工作规范(2016年版)》的要求开展流感疫苗接种工作。接种工作中要注意以下事项:

(1)疫苗瓶有裂纹、标签不清或失效者,疫苗出现浑浊等外观异物者均不得使用。

(2)严格掌握疫苗剂量和适用人群的年龄范围,不能将0.5 ml剂型分为2剂次(每剂次0.25 ml)给2名婴幼儿接种。

(3)接种完成后应告知接种对象留下观察30 min再离开。

(4)建议注射现场备1:1 000肾上腺素等药品和其他抢救设施,以备偶有发生严重过敏反应时供急救使用。

利益冲突 所有作者均声明不存在利益冲突

指南编写专家组:中国疾病预防控制中心传染病管理处冯录召、彭质斌、郑亚明、郑建东、秦颖;中国疾病预防控制中心病毒病预防控制所王大燕、陈涛;北京市疾病预防控制中心传染病地方病控制所杨鹏;复旦大学公共卫生学院杨娟;河南省疾病预防控制中心免疫预防与规划所张延炀;上海市疾病预防控制中心传染病防治所陈健;深圳市南山区疾病预防控制中心免疫规划科姜世强;青海省疾病预防控制中心传染病预防控制所徐莉立;广东省疾病预防控制中心传染病预防控制所康敏

指南编写专家组秘书:苏州市疾病预防控制中心传染病防治科谭亚运;中国疾病预防控制中心传染病管理处张慕丽

审定专家:中国疾病预防控制中心传染病管理处李中杰、冯子健

| [1] |

中华人民共和国国家卫生和计划生育委员会. 流行性感冒诊疗方案(2018年版)[J]. 中华临床感染病杂志, 2018, 11(1): 1-5. National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People's Republic of China. Diagnostic and treatment protocol for influenza (2018 version)Influenza treatment plan (2018 edition)[J]. Chin J Clin Infect Dis, 2018, 11(1): 1-5. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1674-2397.2018.01.001 |

| [2] |

Bischoff WE, Swett K, Leng I, et al. Exposure to influenza virus aerosols during routine patient care[J]. J Infect Dis, 2013, 207(7): 1037-1046. DOI:10.1093/infdis/jis773 |

| [3] |

World Health Organization. Fact sheet on influenza (seasonal)[EB/OL].[2019-09-30]. https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/influenza-(seasonal),2019.

|

| [4] |

李茜, 李霆, 吴绍强, 等. D型流感病毒研究概述[J]. 检验检疫学刊, 2017, 27(04): 73-75. Li Q, Li T, Wu SQ, et al. An overview of research progress on influenza D viruses Overview of Research on Influenza Virus D[J]. J Inspec Quar, 2017, 27(04): 73-75. |

| [5] |

Hause BM, Collin EA, Liu RX, et al. Characterization of a novel influenza virus in cattle and Swine:proposal for a new genus in the Orthomyxoviridae family[J]. mBio, 2014, 5(2): e00031-00014. DOI:10.1128/mBio.00031-14 |

| [6] |

World Health Organization. Vaccines against influenza WHO position paper-November 2012[J]. Wkly Epidemiol Rec, 2012, 87(47): 461-476. |

| [7] |

Nicholson KG, Wood JM, Zambon M. Influenza[J]. Lancet, 2003, 362(9397): 1733-1745. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14854-4 |

| [8] |

Kim DK, Poudel B. Tools to detect influenza virus[J]. Yonsei Med J, 2013, 54(3): 560-566. DOI:10.3349/ymj.2013.54.3.560 |

| [9] |

Kelso JM. Safety of influenza vaccines[J]. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol, 2012, 12(4): 383-388. DOI:10.1097/ACI.0b013e328354395d |

| [10] |

World Health Organization Writing Group, Bell D, Nicoll A, Fukuda K, et al. Non-pharmaceutical interventions for pandemic influenza, international measures[J]. Emerg Infect Dis, 2006, 12(1): 81-87. DOI:10.3201/eid1201.051370 |

| [11] |

Lau LLH, Ip DKM, Nishiura H, et al. Heterogeneity in viral shedding among individuals with medically attended influenza A virus infection[J]. J Infect Dis, 2013, 207(8): 1281-1285. DOI:10.1093/infdis/jit034 |

| [12] |

Carrat F, Vergu E, Ferguson NM, et al. Time lines of infection and disease in human influenza:a review of volunteer challenge studies[J]. Am J Epidemiol, 2008, 167(7): 775-785. DOI:10.1093/aje/kwm375 |

| [13] |

Lipsitch M, Viboud C. Influenza seasonality:lifting the fog[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2009, 106(10): 3645-3646. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0900933106 |

| [14] |

Viboud C, Alonso WJ, Simonsen L. Influenza in tropical regions[J]. PLoS Med, 2006, 3(4): e89. DOI:10.1371/journal.pmed.0030089 |

| [15] |

Azziz Baumgartner E, Dao CN, Nasreen S, et al. Seasonality, timing, and climate drivers of influenza activity worldwide[J]. J Infect Dis, 2012, 206(6): 838-846. DOI:10.1093/infdis/jis467 |

| [16] |

Bloom-Feshbach K, Alonso WJ, Charu V, et al. Latitudinal variations in seasonal activity of influenza and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV):a global comparative review[J]. PLoS One, 2013, 8(2): e54445. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0054445 |

| [17] |

Zou JY, Yang H, Cui HJ, et al. Geographic divisions and modeling of virological data on seasonal influenza in the Chinese mainland during the 2006-2009 monitoring years[J]. PLoS One, 2013, 8(3): e58434. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0058434 |

| [18] |

Yu HJ, Alonso WJ, Feng LZ, et al. Characterization of regional influenza seasonality patterns in China and implications for vaccination strategies:spatio-temporal modeling of surveillance data[J]. PLoS Med, 2013, 10(11): e1001552. DOI:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001552 |

| [19] |

Yang J, Lau YC, Wu P, et al. Variation in influenza B virus epidemiology by Lineage, China[J]. Emerg Infect Dis, 2018, 24(8): 1536-1540. DOI:10.3201/eid2408.180063 |

| [20] |

Somes MP, Turner RM, Dwyer LJ, et al. Estimating the annual attack rate of seasonal influenza among unvaccinated individuals:A systematic review and Meta-analysis[J]. Vaccine, 2018, 36(23): 3199-3207. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.04.063 |

| [21] |

Jayasundara K, Soobiah C, Thommes E, et al. Natural attack rate of influenza in unvaccinated children and adults:a Meta-regression analysis[J]. BMC Infect Dis, 2014, 14: 670. DOI:10.1186/s12879-014-0670-5 |

| [22] |

张惺惺, 吴双胜, 王全意, 等. 北京市2017-2018流行季流感感染率和发病率研究[J]. 国际病毒学杂志, 2019, 26(2): 73-76. Zhang XX, Wu SS, Wang QY, et al. Estimated infection rates and incidence rates of seasonal influenza in Beijing during the 2017-2018 influenza season[J]. Int J Virol, 2019, 26(2): 73-76. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1673-4092.2019.02.001 |

| [23] |

张奕, 潘阳, 赵佳琛, 等. 2016-2018年北京市流行性感冒住院病例的流行病学和临床特征分析[J]. 疾病监测, 2019, 34(7): 626-629. Zhang Y, Pan Y, Zhao JC, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of hospitalizedinpatient influenza patients, cases in Beijing from, 2016 to 2018[J]. Dis Surveill, 2019, 34(7): 626-629. DOI:10.3784/j.issn.1003-9961.2019.07.011 |

| [24] |

Iuliano AD, Roguski KM, Chang HH, et al. Estimates of global seasonal influenza-associated respiratory mortality:a modelling study[J]. The Lancet, 2018, 391(10127): 1285-1300. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)33293-2 |

| [25] |

Li L, Liu YN, Peng W, et al. Influenza-associated excess respiratory mortality in China, 2010-15:a population-based study[J]. Lancet Public Health, 2019, 4(9): e473-e4819. DOI:10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30163-X |

| [26] |

李飒, 刘思家, 朱爱琴, 等. 中国流感死亡负担研究系统综述[J]. 中华预防医学杂志, 2019, 53(10): 1049-1055. Li S, Liu SJ, Zhu AQ, et al. The mortality burden of influenza in China:a systematic review Systematic review of Influenza death burden in China[J]. Chin J Prev Med, 2019, 53(10): 1049-1055. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-9624.2019.10.018 |

| [27] |

Bauch CT, Puig-Barberà J, Natividad-Sancho A, et al. Epidemiology of hospital admissions with influenza during the 2013/2014 northern hemisphere influenza season:Results from the global influenza hospital surveillance network[J]. PLoS One, 2016, 11(5): e0154970. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0154970 |

| [28] |

Peng ZB, Feng LZ, Carolyn GM, et al. Characterizing the epidemiology, virology, and clinical features of influenza in China's first severe acute respiratory infection sentinel surveillance system, February 2011-October 2013[J]. BMC Infect Dis, 2015, 15: 143(1471-2334(Electronic)). DOI: 10.1186%2Fs12879-015-0884-1.

|

| [29] |

Homaira N, Briggs N, Oei JL, et al. Impact of influenza on hospitalization rates in children with a range of chronic lung diseases[J]. Influe Other Res Virus, 2019, 13(3): 233-239. DOI:10.1111/irv.12633 |

| [30] |

Plans-Rubióo P. Prevention and control of influenza in persons with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease[J]. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis, 2007, 2(1): 41-53. |

| [31] |

Goodnight WH, Soper DE. Pneumonia in pregnancy[J]. Crit Care Med, 2005, 33(10 Suppl): S390-397. |

| [32] |

Ohfuji S, Deguchi M, Tachibana D, et al. Estimating influenza disease burden among pregnant women:Application of self-control method[J]. Vaccine, 2017, 35(36): 4811-4816. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.07.006 |

| [33] |

Callaghan WM, Chu SY, Jamieson DJ. Deaths from seasonal influenza among pregnant women in the United States, 1998-2005[J]. Obstet Gynecol, 2010, 115(5): 919-923. DOI:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181d99d85 |

| [34] |

Vilca LM, Verma A, Bonati M, et al. Impact of influenza on outpatient visits and hospitalizations among pregnant women in Catalonia, Spain[J]. J Infect, 2018, 77(6): 553-560. DOI:10.1016/j.jinf.2018.06.015 |

| [35] |

Yu HJ, Feng ZJ, Uyeki TM, et al. Risk factors for severe illness with 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus infection in China[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2011, 52(4): 457-465. DOI:10.1093/cid/ciq144 |

| [36] |

Luteijn JM, Brown MJ, Dolk H. Influenza and congenital anomalies:a systematic review and Meta-analysis[J]. Hum Reprod, 2014, 29(4): 809-823. DOI:10.1093/humrep/det455 |

| [37] |

Steinhoff MC, MacDonald N, Pfeifer D, et al. Influenza vaccine in pregnancy:policy and research strategies[J]. Lancet, 2014, 383(9929): 1611-1613. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60583-3 |

| [38] |

He J, Liu ZW, Lu YP, et al. A systematic review and Meta-analysis of influenza a virus infection during pregnancy associated with an increased risk for stillbirth and low birth weight[J]. Kidney Blood Press Res, 2017, 42(2): 232-243. DOI:10.1159/000477221 |

| [39] |

Fraaij PLA, Heikkinen T. Seasonal influenza:the burden of disease in children[J]. Vaccine, 2011, 29(43): 7524-7528. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.08.010 |

| [40] |

Monto AS, Koopman JS, Longini IM. Tecumseh study of illness. XIII. Influenza infection and disease, 1976-1981[J]. Am J Epidemiol, 1985, 121(6): 811-822. DOI:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114052 |

| [41] |

Cowling BJ, Perera RAPM, Fang VJ, et al. Incidence of influenza virus infections in children in Hong Kong in a 3-year randomized placebo-controlled vaccine study, 2009-2012[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2014, 59(4): 517-524. DOI:10.1093/cid/ciu356 |

| [42] |

高君玫, 陈立凌, 田健美, 等. 2011-2017年苏州市区5岁以下儿童流感相关门诊就诊率的估计[J]. 中华疾病控制杂志, 2019, 23(1): 34-38. Gao JM, Chen LL, Tian JM, et al. The estimation of influenza-related outpatient rate in children under 5 years in Suzhou from 2011 to 2017[J]. Chin J Dis Cont Prev, 2019, 23(1): 34-38. DOI:10.13315/j.cnki.zhjcep.2019.01.008 |

| [43] |

Yu HJ, Huang JG, Huai Y, et al. The substantial hospitalization burden of influenza in central China:surveillance for severe, acute respiratory infection, and influenza viruses, 2010-2012[J]. Influenza Other Respir Viruses, 2014, 8(1): 53-65. DOI:10.1111/irv.12205 |

| [44] |

Finnie TJR, Copley VR, Hall IM, et al. An analysis of influenza outbreaks in institutions and enclosed societies[J]. Epidemiol Infect, 2014, 142(1): 107-113. DOI:10.1017/S0950268813000733 |

| [45] |

Gaglani MJ. Editorial commentary:school-located influenza vaccination:why worth the effort?[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2014, 59(3): 333-335. DOI:10.1093/cid/ciu344 |

| [46] |

Fiore AE, Epperson S, Perrotta D, et al. Expanding the recommendations for annual influenza vaccination to school-age children in the United States[J]. Pediatrics, 2012, 129(Suppl 2): S54-62. DOI:10.1542/peds.2011-0737C |

| [47] |

Wu S, van Asten L, Wang L, et al. Estimated incidence and number of outpatient visits for seasonal influenza in 2015-2016 in Beijing, China[J]. Epidemiol Infect, 2017, 145(16): 3334-3344. DOI:10.1017/S0950268817002369 |

| [48] |

Neuzil KM, Hohlbein C, Zhu YW. Illness among schoolchildren during influenza season:effect on school absenteeism, parental absenteeism from work, and secondary illness in families[J]. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med, 2002, 156(10): 986-991. DOI:10.1001/archpedi.156.10.986 |

| [49] |

Chiu SS, Chan KH, So LY, et al. The population based socioeconomic burden of pediatric influenza-associated hospitalization in Hong Kong[J]. Vaccine, 2012, 30(10): 1895-1900. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.12.027 |

| [50] |

Kuster SP, Shah PS, Coleman BL, et al. Incidence of influenza in healthy adults and healthcare workers:a systematic review and Meta-analysis[J]. PLoS One, 2011, 6(10): e26239. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0026239 |

| [51] |

Seto WH, Cowling BJ, Lam H-S, et al. Clinical and nonclinical health care workers faced a similar risk of acquiring 2009 pandemic H1N1 infection[J]. Clin Intect Dis, 2011, 53(3): 280-283. DOI:10.1093/cid/cir375 |

| [52] |

Lietz J, Westermann C, Nienhaus A, et al. The occupational risk of influenza A (H1N1) infection among healthcare personnel during the 2009 pandemic:A systematic review and Meta-analysis of observational studies[J]. PLoS One, 2016, 11(8): e0162061. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0162061 |

| [53] |

Kumar S, Fan J, Melzer-Lange M, et al. H1N1 hemagglutinin-inhibition seroprevalence in Emergency Department Health Care workers after the first wave of the 2009 influenza pandemic[J]. Pediatric Emergency Care, 2011, 27(9): 804-807. DOI:10.1097/PEC.0b013e31822c125e |

| [54] |

Salgado CD, Farr BM, Hall KK, et al. Influenza in the acute hospital setting[J]. Lancet Infect Dis, 2002, 2(3): 145-155. DOI:10.1016/S1473-3099(02)00221-9 |

| [55] |

Elder AG, O'Donnell B, MccCruden EAB, et al. Incidence and recall of influenza in a cohort of Glasgow healthcare workers during the 1993-4 epidemic:results of serum testing and questionnaire[J]. BMJ, 1996, 313(7067): 1241-1242. DOI:10.1136/bmj.313.7067.1241 |

| [56] |

Nielsen J, Vestergaard LS, Richter L, et al. European all-cause excess and influenza-attributable mortality in the 2017/18 season:should the burden of influenza B be reconsidered?[J]. Clin Microbiol Infect, 2019, 25(10): 1266-1276. DOI:10.1016/j.cmi.2019.02.011 |

| [57] |

Wang H, Fu CX, Li KB, et al. Influenza associated mortality in Southern China, 2010-2012[J]. Vaccine, 2014, 32(8): 973-978. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.12.013 |

| [58] |

Yang L, Ma S, Chen PY, et al. Influenza associated mortality in the subtropics and tropics:Results from three Asian cities[J]. Vaccine, 2011, 29(48): 8909-8914. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.09.071 |

| [59] |

Wu P, Goldstein E, Ho LM, et al. Excess mortality associated with influenza A and B virus in Hong Kong, 1998-2009[J]. J Infect Dis, 2012, 206(12): 1862-1871. DOI:10.1093/infdis/jis628 |

| [60] |

Chow A, Ma S, Ling AE, et al. Influenza-associated deaths in tropical Singapore[J]. Emerging Infect Dis, 2006, 12(1): 114-121. DOI:10.3201/eid1201.050826 |

| [61] |

Nunes B, Viboud C, Machado A, et al. Excess mortality associated with influenza epidemics in Portugal, 1980 to 2004[J]. PLoS One, 2011, 6(6): e20661. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0020661 |

| [62] |

Thompson WW, Shay DK, Weintraub E, et al. Mortality associated with influenza and respiratory syncytial virus in the United States[J]. JAMA, 2003, 289(2): 179-186. DOI:10.1001/jama.289.2.179 |

| [63] |

Feng LZ, Shay DK, Jiang Y, et al. Influenza-associated mortality in temperate and subtropical Chinese cities, 2003-2008[J]. Bull World Health Organ, 2012, 90(4): 279-288B. DOI:10.2471/BLT.11.096958 |

| [64] |

Yu HJ, Huang JG, Huai Y, et al. The substantial hospitalization burden of influenza in central C hina:surveillance for severe, acute respiratory infection, and influenza viruses, 2010-2012[J]. Influe Other Resp Viruses, 2014, 8(1): 53-65. DOI:10.1111/irv.12205 |

| [65] |

Guo RN, Zheng HZ, Li JS, et al. A population-based study on incidence and economic burden of influenza-like illness in south China, 2007[J]. Public Health, 2011, 125(6): 389-395. DOI:10.1016/j.puhe.2011.03.004 |

| [66] |

Yang J, Jit M, Leung KS, et al. The economic burden of influenza-associated outpatient visits and hospitalizations in China:a retrospective survey[J]. Infect Dis Poverty, 2015, 4: 44. DOI:10.1186/s40249-015-0077-6 |

| [67] |

Chen J, Li YT, Gu BK, et al. Estimation of the direct cost of treating people aged more than 60 years infected by influenza virus in Shanghai[J]. Asia Pac J Public Health, 2015, 27(2): NP936-NP946. DOI:10.1177/1010539512460269 |

| [68] |

于佳, 张涛, 王胤, 等. 苏州市2011-2017年5岁以下儿童流感门诊病例临床特征及疾病负担[J]. 中华流行病学杂志, 2018, 39(6): 847-851. Yu J, Zhang T, Wang Y, et al. Clinical characteristics and economic burden of influenza among children under 5 years old, in Suzhou, 2011-2017[J]. Chin J Epidemiol, 2018, 39(6): 847-851. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2018.06.029 |

| [69] |

Yang JM, Jit M, Zheng YM, et al. The impact of influenza on the health related quality of life in China:an EQ-5D survey[J]. BMC Infect Dis, 2017, 17(1): 686. DOI:10.1186/s12879-017-2801-2 |

| [70] |

Chan SS. Does vaccinating ED health care workers against influenza reduce sickness absenteeism?[J]. Am J Emerg Med, 2007, 25(7): 808-811. DOI:10.1016/j.ajem.2007.02.002 |

| [71] |

Cate TR, Couch RB, Parker D, et al. Reactogenicity, immunogenicity, and antibody persistence in adults given inactivated influenza virus vaccines-1978[J]. Rev Infect Dis, 1983, 5(4): 737-747. DOI:10.1093/clinids/5.4.737 |

| [72] |

Ochiai H, Shibata M, Kamimura K, et al. Evaluation of the efficacy of split-product trivalent A(H1N1), A(H3N2), and B influenza vaccines:reactogenicity, immunogenicity and persistence of antibodies following two doses of vaccines[J]. Microbiol Immunol, 1986, 30(11): 1141-1149. DOI:10.1111/j.1348-0421.1986.tb03043.x |

| [73] |

Küunzel W, Glathe H, Engelmann H, et al. Kinetics of humoral antibody response to trivalent inactivated split influenza vaccine in subjects previously vaccinated or vaccinated for the first time[J]. Vaccine, 1996, 14(12): 1108-1110. DOI:10.1016/0264-410X(96)00061-8 |

| [74] |

Song JY, Cheong HJ, Hwang IS, et al. Long-term immunogenicity of influenza vaccine among the elderly:Risk factors for poor immune response and persistence[J]. Vaccine, 2010, 28(23): 3929-3935. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.03.067 |

| [75] |

Feng S, Chiu SS, Chan ELY, et al. Effectiveness of influenza vaccination on influenza-associated hospitalisations over time among children in Hong Kong:a test-negative case-control study[J]. Lancet Respir Med, 2018, 6(12): 925-934. DOI:10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30419-3 |

| [76] |

Ramsay LC, Buchan SA, Stirling RG, et al. The impact of repeated vaccination on influenza vaccine effectiveness:a systematic review and Meta-analysis[J]. BMC Med, 2019, 17(1): 9. DOI:10.1186/s12916-018-1239-8 |

| [77] |

Osterholm MT, Kelley NS, Sommer A, et al. Efficacy and effectiveness of influenza vaccines:a systematic review and Meta-analysis[J]. Lancet Infect Dis, 2012, 12(1): 36-44. DOI:10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70295-X |

| [78] |

Jefferson T, di Pietrantonj C, Demicheli V, et al. Vaccines for preventing influenza in healthy adults[J]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 20180, 2(7): CD001269. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001269.pub4.

|

| [79] |

星一, 刘民. 流感灭活疫苗在中国应用效果的Meta分析[J]. 中华流行病学杂志, 2009, 30(4): 368-370. Xing Y, Liu M. Meta analysis on the effectiveness of inactivated influenza vaccine[J]. Chin J Epidemiol, 2009, 30(4): 368-370. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2009.04.015 |

| [80] |

Belongia EA, Simpson MD, King JP, et al. Variable influenza vaccine effectiveness by subtype:a systematic review and Meta-analysis of test-negative design studies[J]. Lancet Infect Dis, 2016, 16(8): 942-951. DOI:10.1016/S1473-3099(16)00129-8 |

| [81] |

Moa AM, Chughtai AA, Muscatello DJ, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of inactivated quadrivalent influenza vaccine in adults:A systematic review and Meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials[J]. Vaccine, 2016, 34(35): 4092-4102. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.06.064 |

| [82] |

Bekkat-Berkani R, Ray R, Jain VK, et al. Evidence update:GlaxoSmithKline's inactivated quadrivalent influenza vaccines[J]. Expert Rev Vaccines, 2016, 15(2): 201-214. DOI:10.1586/14760584.2016.1113878 |

| [83] |

Steinhoff MC, Omer SB, Roy E, et al. Influenza immunization in pregnancy-antibody responses in mothers and infants[J]. N Engl J Med, 2010, 362(17): 1644-1646. DOI:10.1056/NEJMc0912599 |

| [84] |

Nunes MC, Madhi SA. Influenza vaccination during pregnancy for prevention of influenza confirmed illness in the infants:A systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Hum Vaccin Immunother, 2018, 14(3): 758-766. DOI:10.1080/21645515.2017.1345385 |

| [85] |

Cuningham W, Geard N, Fielding JE, et al. Optimal timing of influenza vaccine during pregnancy:A systematic review and Meta-analysis[J]. Influe Other Respir Viruses, 2019, 13(5): 438-452. DOI:10.1111/irv.12649 |

| [86] |

Fu CX, He Q, Li ZT, et al. Seasonal influenza vaccine effectiveness among children, 2010-2012[J]. Influenza Other Respir Viruses, 2013, 7(6): 1168-1174. DOI:10.1111/irv.12157 |

| [87] |

Neuzil KM, Jackson LA, Nelson J, et al. Immunogenicity and reactogenicity of 1 versus 2 doses of trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine in vaccine-naive 5-8-year-old children[J]. J Infect Dis, 2006, 194(8): 1032-1039. DOI:10.1086/507309 |

| [88] |

Shinjoh M, Sugaya N, Furuichi M, et al. Effectiveness of inactivated influenza vaccine in children by vaccine dose, 2013-18[J]. Vaccine, 2019, 37(30): 4047-4054. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.05.090 |

| [89] |

Chua H, Chiu SS, Chan ELY, et al. Effectiveness of partial and full influenza vaccination in among children aged < 9 years in Hong Kong, 2011-2019[J]. J Infect Dis, 2019, 220(10): 1568-1576. DOI:10.1093/infdis/jiz361 |

| [90] |

Pepin S, Szymanski H, Rochin Kobashi IA, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of an intramuscular quadrivalent influenza vaccine in children 3 to 8 y of age:A phase Ⅲ randomized controlled study[J]. Hum Vaccin Immunother, 2016, 12(12): 3072-3078. DOI:10.1080/21645515.2016.1212143 |

| [91] |

Chiu SS, Kwan MYW, Feng S, et al. Interim estimate of influenza vaccine effectiveness in hospitalised children, Hong Kong, 2017/18[J]. Euro Surveill, 2018, 23(8): pii=18-00062. DOI: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2018.23.8.18-00062.

|

| [92] |

Zhang Y, Cao ZD, Costantino V, et al. Influenza illness averted by influenza vaccination among school year children in Beijing, 2013-2016[J]. Influenza Other Respir Viruses, 2018, 12(6): 687-694. DOI:10.1111/irv.12585 |

| [93] |

Wu SS, Pan Y, Zhang XX, et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness in preventing laboratory-confirmed influenza in outpatient settings:A test-negative case-control study in Beijing, China, 2016/17 season[J]. Vaccine, 2018, 36(38): 5774-5780. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.07.077 |

| [94] |

Zhang L, Yang P, Thompson MG, et al. Influenza Vaccine effectiveness in preventing influenza illness among children during school-based outbreaks in the 2014-2015 season in Beijing, China[J]. Pediatr Infect Dis J, 2017, 36(3): e69-75. DOI:10.1097/INF.0000000000001434 |

| [95] |

Duan W, Zhang L, Wu SS, et al. Reduction of influenza A(H3N2)-associated symptoms by influenza vaccination in school aged-children during the 2014-2015 winter season dominated by mismatched H3N2 viruses[J]. Hum Vaccin Immunother, 2019, 15(5): 1031-1034. DOI:10.1080/21645515.2019.1575573 |

| [96] |

Pan Y, Wang QY, Yang P, et al. Influenza vaccination in preventing outbreaks in schools:A long-term ecological overview[J]. Vaccine, 2017, 35(51): 7133-7138. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.10.096 |

| [97] |

Demicheli V, Jefferson T, di Pietrantonj C, et al. Vaccines for preventing influenza in the elderly[J]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2010, 8(2): CD004876. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD004876.pub3 |

| [98] |

Jackson ML, Chung JR, Jackson LA, et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness in the united states during the 2015-2016 season[J]. N Engl J Med, 2017, 377(6): 534-543. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa1700153 |

| [99] |

Flannery B, Chung JR, Thaker SN, et al. Interim estimates of 2016-17 seasonal influenza vaccine effectiveness-United States, February 2017[J]. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 2017, 66(6): 167-171. DOI:10.15585/mmwr.mm6606a3 |

| [100] |

Flannery B, Chung JR, Belongia EA, et al. Interim estimates of 2017-18 seasonal influenza vaccine effectiveness-United States, February 2018[J]. Am J Transplant, 2018, 18(4): 1020-1025. DOI:10.1111/ajt.14730 |

| [101] |

Darvishian M, van den Heuvel ER, Bissielo A, et al. Effectiveness of seasonal influenza vaccination in community-dwelling elderly people:an individual participant data meta-analysis of test-negative design case-control studies[J]. Lancet Respir Med, 2017, 5(3): 200-211. DOI:10.1016/S2213-2600(17)30043-7 |

| [102] |

Beyer WEP, McElhaney J, Smith DJ, et al. Cochrane re-arranged:support for policies to vaccinate elderly people against influenza[J]. Vaccine, 2013, 31(50): 6030-6033. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.09.063 |

| [103] |

黄远东, 赵晓平, 万涛, 等. 慢性阻塞性肺病人群流感疫苗接种的效果观察[J]. 海南医学, 2011, 22(4): 29-31. Huang YD, Zhao XP, Wan T, et al. Effects of influenza vaccination in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease[J]. Hai-nan Med J, 2011, 22(4): 29-31. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1003-6350.2011.04.011 |

| [104] |

高忠翠, 李江涛, 展胜. 卡舒宁联合流感疫苗对老年性慢性支气管炎合并急性感染的防治效果[J]. 中国生物制品学杂志, 2011, 24(10): 1214-1216. Gao ZC, Li JT, Zhan S. Preventive and curative effects of Card Shu Ning Combined with Influenza Vaccine on senile chronic bronchitis complicated with acute infection[J]. Chin J Biol, 2011, 24(10): 1214-1216. |

| [105] |

Schwarze J, Openshaw P, Jha A, et al. Influenza burden, prevention, and treatment in asthma-A scoping review by the EAACI Influenza in asthma task force[J]. Allergy, 2018, 73(6): 1151-1181. DOI:10.1111/all.13333 |

| [106] |

Vasileiou E, Sheikh A, Butler C, et al. Effectiveness of influenza vaccines in asthma:A systematic review and Meta-analysis[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2017, 65(8): 1388-1395. DOI:10.1093/cid/cix524 |

| [107] |

Clar C, Oseni Z, Flowers N, et al. Influenza vaccines for preventing cardiovascular disease[J]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2015(5): Cd005050. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD005050.pub3 |

| [108] |

Sribhutorn A, Phrommintikul A, Wongcharoen W, et al. Influenza vaccination in acute coronary syndromes patients in Thailand:the cost-effectiveness analysis of the prevention for cardiovascular events and pneumonia[J]. J Geriatr Cardiol, 2018, 15(6): 413-421. DOI:10.11909/j.issn.1671-5411.2018.07.008 |

| [109] |

Suh J, Kim B, Yang Y, et al. Cost effectiveness of influenza vaccination in patients with acute coronary syndrome in Korea[J]. Vaccine, 2017, 35(21): 2811-2817. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.04.016 |

| [110] |

Seo YB, Baek JH, Lee J, et al. Long-term immunogenicity and safety of a conventional influenza vaccine in patients with type 2 diabetes[J]. Clin Vaccine Immunol, 2015, 22(11): 1160-1165. DOI:10.1128/CVI.00288-15 |

| [111] |

Goeijenbier M, van Sloten TT, Slobbe L, et al. Benefits of flu vaccination for persons with diabetes mellitus:A review[J]. Vaccine, 2017, 35(38): 5095-5101. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.07.095 |

| [112] |

Collins JP, Campbell AP, Openo K, et al. Clinical features and outcomes of immunocompromised children hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed influenza in the United States, 2011-2015[J]. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc, 2018. DOI:10.1093/jpids/piy101 |

| [113] |

Kliner M, Keenan A, Sinclair D, et al. Influenza vaccination for healthcare workers in the UK:appraisal of systematic reviews and policy options[J]. BMJ Open, 2016, 6(9): e012149. DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012149 |

| [114] |

Ng ANM, Lai CKY. Effectiveness of seasonal influenza vaccination in healthcare workers:a systematic review[J]. J Hospital Infect, 2011, 79(4): 279-286. DOI:10.1016/j.jhin.2011.08.004 |

| [115] |

Imai C, Toizumi M, Hall L, et al. A systematic review and Meta-analysis of the direct epidemiological and economic effects of seasonal influenza vaccination on healthcare workers[J]. PLoS One, 2018, 13(6): e0198685. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0198685 |

| [116] |

Vanhems P, Baghdadi Y, Roche S, et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness among healthcare workers in comparison to hospitalized patients:A 2004-2009 case-test, negative-control, prospective study[J]. Hum Vaccin Immunother, 2016, 12(2): 485-490. DOI:10.1080/21645515.2015.1079677 |

| [117] |

吴承菊, 郑修霞, 孙菲, 等. 医务人员接种流感疫苗的效果分析[J]. 中国实用护理杂志, 2008, 24(17): 57-59. Wu CJ, Zheng XX, Sun F, et al. Effect analysis of influenza vaccination among medical staff[J]. Chin J Pract Nurs, 2008, 24(17): 57-59. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1672-7088.2008.17.029 |

| [118] |

刘民, 刘改芬, 赵伟, 等. 医务人员接种流感疫苗的效果及效益研究[J]. 中国全科医学, 2006, 9(9): 708-711. Liu M, Liu GF, Zhao W, et al. An effect and cost-benefit analysis of influenza vaccine among the healthcare worker[J]. Chin Gen Pract, 2006, 9(9): 708-711. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1007-9572.2006.09.006 |

| [119] |

de Lusignan S, Dos Santos G, Byford R, et al. Enhanced safety surveillance of seasonal quadrivalent influenza vaccines in English primary care:Interim analysis[J]. Adv Ther, 2018, 35(8): 1199-1214. DOI:10.1007/s12325-018-0747-4 |

| [120] |

Greenberg DP, Robertson CA, Landolfi VA, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of an inactivated quadrivalent influenza vaccine in children 6 months through 8 years of age[J]. Pediatr Infect Dis J, 2014, 33(6): 630-636. DOI:10.1097/INF.0000000000000254 |

| [121] |

Tsurudome Y, Kimachi K, Okada Y, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of an inactivated quadrivalent influenza vaccine in healthy adults:a phase Ⅱ, open-label, uncontrolled trial in Japan[J]. Microbiol Immunol, 2015, 59(10): 597-604. DOI:10.1111/1348-0421.12316 |

| [122] |

Tinoco JC, Pavia-Ruz N, Cruz-Valdez A, et al. Immunogenicity, reactogenicity, and safety of inactivated quadrivalent influenza vaccine candidate versus inactivated trivalent influenza vaccine in healthy adults aged ≥ 18 years:a phase Ⅲ, randomized trial[J]. Vaccine, 2014, 32(13): 1480-1487. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.01.022 |

| [123] |

Statler VA, Albano FR, Airey J, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of a quadrivalent inactivated influenza vaccine in children 6-59 months of age:A phase 3, randomized, noninferiority study[J]. Vaccine, 2019, 37(2): 343-351. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.07.036 |

| [124] |

van de Witte S, Nauta J, Montomoli E, et al. A Phase Ⅲ randomised trial of the immunogenicity and safety of quadrivalent versus trivalent inactivated subunit influenza vaccine in adult and elderly subjects, assessing both anti-haemagglutinin and virus neutralisation antibody responses[J]. Vaccine, 2018, 36(40): 6030-6038. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.04.043 |

| [125] |

Haber P, Moro PL, Lewis P, et al. Post-licensure surveillance of quadrivalent inactivated influenza (IIV4) vaccine in the United States, Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS), July 1, 2013-May 31, 2015[J]. Vaccine, 2016, 34(22): 2507-2512. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.03.048 |

| [126] |

胡昱, 李倩, 陈雅萍, 等. 18岁以上人群接种四价流感病毒灭活疫苗免疫原性和安全性的Meta分析[J]. 国际流行病学传染病学杂志, 2017, 44(1): 47-52. Hu Y, Li Q, Chen YP, et al. Meta-analysis on immunogenicity and safety of inactivated quadrivalent influenza vaccine in adults aged above 18 years[J]. Inter J Epidemiol Infect Dis, 2017, 44(1): 47-52. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1673-4149.2017.01.010 |

| [127] |

Gandhi-Banga S, Chabanon AL, Eymin C, et al. Enhanced passive safety surveillance of three marketed influenza vaccines in the UK and the Republic of Ireland during the 2017/18 season[J]. Human Vacc Immun, 2019, 15(9): 2154-2158. DOI:10.1080/21645515.2019.1581538apeutics |

| [128] |

张佩如, 祝小平, 周良君, 等. 国产流行性感冒病毒裂解疫苗安全性及免疫效果观察[J]. 中华预防医学杂志, 2009, 43(7): 615-618. Zhang PR, Zhu XP, Zhou LJ, et al. Safety and immunological effect of domestic split influenza virus vaccine[J]. Chin J Prev Med, 2009, 43(7): 615-618. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-9624.2009.07.019 |

| [129] |

孙立娜, 李丽芳, 刘静芹, 等. 国产与进口流感疫苗接种的临床观察[J]. 中国免疫学杂志, 2014, 30(1): 77-79. Sun LN, Li LF, Liu JQ, et al. Clinical observation of domestic and imported influenza vaccination[J]. Chin J Immunol, 2014, 30(1): 77-79. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1000-484X.2014.01.015 |

| [130] |

胡锦流, 王仪, 范刚, 等. 流行性感冒裂解疫苗临床安全性及免疫原性研究[J]. 现代预防医学, 2006, 33(5): 828-829. Hu JL, Wang Y, Fan G, et al. Study on clinical safety and immunogenicity of influenza lysing vaccine[J]. Mod Prev Med, 2006, 33(5): 828-829. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1003-8507.2006.05.077 |

| [131] |

武文娣, 李克莉, 许涤沙, 等. 中国2015-2018年3个流感季节流感疫苗疑似预防接种异常反应监测数据分析[J]. 中华预防医学杂志, 2019, 53(10): 987-992. Wu WD, Li KL, Xu DS, et al. Study on surveillance data of adverse events following immunization of seasonal influenza vaccine in China during 2015-2018 influenza seasonData analysis of monitoring abnormal response of influenza vaccines in China from 2015 to 2018[J]. Chin J Prev Med, 2019, 53(10): 987-992. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-9624.2019.10.007 |

| [132] |

Peasah SK, Azziz-Baumgartner E, Breese J, et al. Influenza cost and cost-effectiveness studies globally-a review[J]. Vaccine, 2013, 31(46): 5339-5348. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.09.013 |

| [133] |

Ting EEK, Sander B, Ungar WJ. Systematic review of the cost-effectiveness of influenza immunization programs[J]. Vaccine, 2017, 35(15): 1828-1843. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.02.044 |

| [134] |

陈晨, 刘国恩, 王美娇, 等. 中国老人接种流感疫苗的成本效果分析[J]. 中华预防医学杂志, 2019, 53(10): 993-999. Chen C, Liu GE, Wang MJ, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of Chinese elderly vaccination againstseasonal influenza vaccine in elderly Chinese population[J]. Chin J Prev Med, 2019, 53(10): 993-999. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-9624.2019.10.0087 |

| [135] |

杨娟, 严涵, 冯录召, 等. 中国糖尿病患者免费接种流感疫苗的成本效果分析[J]. 中华预防医学杂志, 2019, 53(10): 1000-1006. Yang J, Yan H, Feng LZ, et al. Cost-effectiveness of potential government fully-funded influenza vaccination in population with diabetes in China Cost-effectiveness analysis of free influenza vaccination for Chinese diabetes patients[J]. Chin J Prev Med, 2019, 53(10): 1000-1006. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-9624.2019.10.009 |

| [136] |

des Roches A, Paradis L, Gagnon R, et al. Egg-allergic patients can be safely vaccinated against influenza[J]. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 2012, 130(5): 1213-1216. DOI:10.1016/j.jaci.2012.07.046 |

| [137] |

des Roches A, Samaan K, Graham F, et al. Safe vaccination of patients with egg allergy by using live attenuated influenza vaccine[J]. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract, 2015, 3(1): 138-139. DOI:10.1016/j.jaip.2014.08.008 |

| [138] |

Turner PJ, Southern J, Andrews NJ, et al. Safety of live attenuated influenza vaccine in atopic children with egg allergy[J]. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 2015, 136(2): 376-381. DOI:10.1016/j.jaci.2014.12.1925 |

| [139] |

Turner PJ, Southern J, Andrews NJ, et al. Safety of live attenuated influenza vaccine in young people with egg allergy:multicentre prospective cohort study[J]. BMJ, 2015, 351: h6291. DOI:10.1136/bmj.h6291 |

| [140] |

USCDC. Prevention and Control of Seasonal Influenza with Vaccines: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices-United States, 2017-18 Influenza Season[EB/OL].(2017-08-25)[2018-09-04]. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/acip-recs/vacc-specific/downloads/ACIP-recs-2017-18-bkgd.pdf.

|

| [141] |

Grohskopf LA, Sokolow LZ, Broder KR, et al. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines:recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices-United States, 2018-19 influenza season[J]. MMWR Recomm Rep, 2018, 67(3): 1-20. DOI:10.15585/mmwr.rr6703a1 |

| [142] |

Kerzner B, Murray AV, Cheng E, et al. Safety and immunogenicity profile of the concomitant administration of ZOSTAVAX and inactivated influenza vaccine in adults aged 50 and older[J]. J Am Geriatr Soc, 2007, 55(10): 1499-1507. DOI:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01397.x |

| [143] |

Ofori-Anyinam O, Leroux-Roels G, Drame M, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of an inactivated quadrivalent influenza vaccine co-administered with a 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine versus separate administration, in adults ≥ 50 years of age:Results from a phase Ⅲ, randomized, non-inferiority trial[J]. Vaccine, 2017, 35(46): 6321-6328. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.09.012 |

| [144] |

Chang YC, Chou YJ, Liu JY, et al. Additive benefits of pneumococcal and influenza vaccines among elderly persons aged 75 years or older in Taiwan-a representative population-based comparative study[J]. J Infect, 2012, 65(3): 231-238. DOI:10.1016/j.jinf.2012.04.014 |

| [145] |

Christenson B, Pauksen K, Sylvan SP. Effect of influenza and pneumococcal vaccines in elderly persons in years of low influenza activity[J]. Virol J, 2008, 5: 52. DOI:10.1186/1743-422X-5-52 |

| [146] |

Yin MJ, Huang LF, Zhang Y, et al. Effectiveness and safety of dual influenza and pneumococcal vaccination versus separate administration or no vaccination in older adults:a meta-analysis[J]. Expert Rev Vaccines, 2018, 17(7): 653-663. DOI:10.1080/14760584.2018.1495077 |

| [147] |

Poscia A, Collamati A, Carfi A, et al. Influenza and pneumococcal vaccination in older adults living in nursing home:a survival analysis on the shelter study[J]. Eur J Public Health, 2017, 27(6): 1016-1020. DOI:10.1093/eurpub/ckx150 |

| [148] |

Li CH, Gubbins PO, Chen GJ. Prior pneumococcal and influenza vaccinations and in-hospital outcomes for community-acquired pneumonia in elderly veterans[J]. J Hosp Med, 2015, 10(5): 287-293. DOI:10.1002/jhm.2328 |

| [149] |

Farkas K, Terhes G, Deáak J, et al. The efficiency of influenza vaccines in patients with inflammatory bowel disease on immunosuppressive therapy[J]. Orv Hetil, 2012, 153(47): 1870-1874. DOI:10.1556/OH.2012.29484 |

| [150] |

Huemer HP. Possible immunosuppressive effects of drug exposure and environmental and nutritional effects on infection and vaccination[J]. Med Inflamm, 2015, 2015: 349176. DOI:10.1155/2015/349176 |

2019, Vol. 40

2019, Vol. 40