文章信息

- 孟玲先, 阙喜妹, 高雪, 王彤.

- Meng Lingxian, Que Ximei, Gao Xue, Wang Tong.

- 儿童肥胖与冠状动脉疾病的孟德尔随机化研究

- Childhood obesity and coronary artery disease:a Mendelian randomization study

- 中华流行病学杂志, 2019, 40(7): 839-843

- Chinese journal of Epidemiology, 2019, 40(7): 839-843

- http://dx.doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2019.07.019

-

文章历史

收稿日期: 2018-11-14

冠状动脉疾病(coronary artery disease,CAD)是全球人口发病和死亡的主要原因,已成为全球性的医学问题。CAD患者存在着心肌梗死、缺血性中风和心血管死亡的巨大风险,而上述并发症目前的治疗方案成本较高、疗效并不显著,给患者及其家庭、所在国家带来巨大的卫生经济负担[1-2]。在过去的几十年中,儿童肥胖的增长率几乎是成年人的两倍[3],肥胖已成为全球流行病,同时,CAD的发病率也在持续上升,这意味着两者之间可能具有一定的关联。而已有的观察性研究表明,儿童期较高的BMI会增加CAD发病风险[4],且儿童肥胖者在其成年期患CAD的风险要高于一般的成年肥胖者[5]。但是,传统的观察性研究结果可能受到社会经济地位、无法测量的生活方式等混杂因素的干扰,甚至产生逆向因果关联[6]。近年,孟德尔随机化研究(MR)方法已被广泛用于评估危险因素和疾病的潜在因果关系。MR方法类似于随机对照试验(RCT),由于基因型随机化是在受孕时发生的,所以不太可能受到混杂因素和反向因果关系的影响,因此利用遗传变异作为工具变量进行MR分析可以得到偏倚较小的因果效应值[7]。在MR分析中作为工具变量的遗传变异必须满足3个假设[8]:必须与儿童BMI相关,独立于混杂因素,只能通过儿童BMI影响CAD。其中,第二个和第三个假设被称为无多效性假设。近年相关的MR表明,成年人肥胖与CAD的发生具有因果关联[9]。然而,关于儿童肥胖对CAD的因果影响还不够明确。因此,本研究利用MR方法分析儿童肥胖与CAD之间是否存在因果关联,为儿童肥胖与CAD发病风险之间的关联提供遗传学支持。

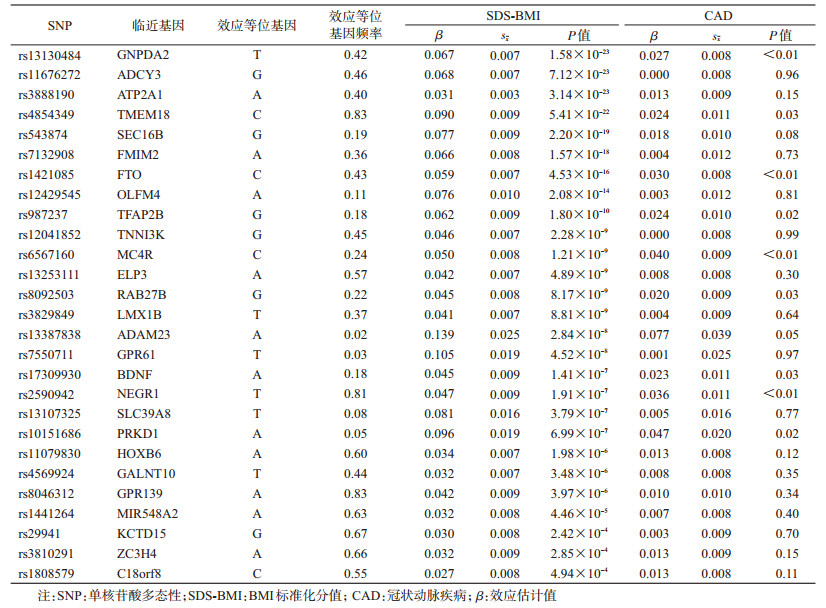

资料与方法1.数据源与工具变量的筛选:儿童BMI的数据源于早期生长遗传学(Early Growth Genetics Consortium,EGG)数据库(http://www.egg-consortium.org/)[10]和人体测量学特征遗传学研究数据库(Genetic Investigation of ANthropometric Traits,GIANT)(http://portals.broadinstitute.org/collaboration/giant/index.php/GIANT_consortium)[11]。EGG数据库汇总了多个人类早期生长遗传的全基因组关联研究(GWAS)数据,以确定对人类早期生长相关性状有影响的基因位点。GIANT汇总了与人体测量学相关的GWAS数据和其他大规模遗传学研究的数据,旨在确定调节人体身高、肥胖等相关基因位点。为了选择合适的遗传变异作为研究儿童肥胖的工具变量,本研究使用目前样本量最大的关于儿童肥胖GWAS的Meta分析数据,该数据包括20项探索研究阶段的35 668名儿童,以及13项重复研究阶段的11 873名儿童,其中儿童肥胖是以2~10岁欧洲儿童BMI标准化分值(SDS-BMI)衡量的。该研究识别了与儿童BMI相关的15个单核苷酸多态性(single nucleotide polymorphisms,SNP)位点,并解释了2.0%与儿童BMI相关的遗传变异[10]。

本研究采用以下标准筛选与儿童肥胖有关的遗传变异作为工具变量:①GWAS中与儿童SDS-BMI有关的15个SNP(P<5×10-8)[10];②在探索和联合分析中,与儿童肥胖存在潜在性关联(P<5×10-6)并且与成年人BMI关联(Bonferroni调整后的P<0.005 5)[11],以及在儿童和成年人中具有一致效应方向的7个SNP;③GWAS中具有显著关联,并且与成年人BMI[11]和儿童BMI(Bonferroni调整的P<5×10-4)具有一致效应方向的22个SNP。当标准③与前2个标准存在重叠时,优先满足前2个标准,每个遗传基因座保留1个标记,共筛选出27个符合标准的SNP作为工具变量。

CAD的汇总数据源于CARDIoGRAMplusC4D [Coronary Artery Disease Genome Wide Replication and Meta-analysis(CARDIoGRAM)plus the Coronary Artery Disease(C4D)Genetics]数据库(http://www.cardiogramplusc4d.org/)。该数据库汇集了多个大规模CAD和心肌梗死的遗传学研究数据,以确定与CAD和心肌梗死发病有关的风险位点。本研究CAD的汇总数据包含的个体均源于欧洲最大的队列UK Biobank,2015年7月UK Biobank发布的CAD病例包含自述具有心绞痛的个体或具有其他证据的慢性CAD患者。作为工具变量的27个SNP与CAD的关联结果是从Nelson等[12]进行的CAD GWAS中提取的,CAD病例定义为致死性或非致死性心肌梗死、经皮冠状动脉腔内成形术、冠状动脉旁路移植术、慢性缺血性心脏病和心绞痛的个体。该研究专门成立了UKBiobank-Cardio Metabolic-Consortium CHD工作组对数据进行质控。该研究样本量为148 172人(病例10 801人,对照137 371人)。其中CAD病例年龄为(61.56±6.14)岁,男性7 422人(68.7%);对照组年龄为(56.23±8.02)岁,男性62 342人(45.4%)。

2.工具变量多效性检验:采用MR-Egger方法对工具变量进行多效性检验[13],检验Meta分析中的发表偏倚。MR-Egger方法的模型表示为:

其中Γj表示工具变量与CAD之间的效应值,λj表示工具变量与儿童BMI的效应值,β0表示工具变量多效性效应的平均值,根据β0的95%CI是否包括0评估工具变量是否具有多效性。β表示儿童肥胖与CAD之间的因果效应估计值。

3.主分析:对于作为工具变量的27个SNP,使用有关儿童肥胖GWAS的汇总数据中工具变量与儿童BMI的效应估计值(β)和sx以及有关CAD GWAS的汇总数据中工具变量与CAD的效应估计值(β)和sx计算因果效应。本研究采用基于众数的方法(mode-based estimate,MBE)作为主分析,估计儿童BMI对成年期患CAD的因果效应。与其他MR方法相比,采用MBE进行因果推断时,如果所有的假设条件都满足,可得到偏倚最小的因果估计值,并且Ⅰ类错误率也最小。即使存在较多的无效工具变量,也可得到较为一致的因果效应估计值[14]。

4.敏感性分析:利用MR方法进行因果推断时,目前并没有一个适合于所有研究的“金标准”,每种都具有各自的优缺点。目前相关的研究建议:当用多个遗传变异作为工具变量时,应同时使用多种MR方法估计因果效应[15-16]。因此,除运用MBE进行主分析外,本研究还采用逆方差加权(Inverse-Variance Weighted,IVW)、简单中位数(Simple Median Estimator,SME)、加权中位数(Weighted Median Estimator,WME)法进行敏感性分析并将其结果与主分析的结果进行比较。

5.统计学分析:使用R 3.5.1软件中的MendelianRandomization软件包(http://cnsgenomics.com/software/MendelianRandomization)进行统计学分析。

结果1.工具变量筛选:根据本研究工具变量的筛选标准进行筛选,最终选定27个SNP作为工具变量,基本信息见表 1。

2.工具变量多效性检验:MR-Egger回归得到的截距项为0.005,对其进行假设检验,95%CI为-0.008~0.018,包含0,P=0.432,提示所选取的工具变量不具有多效性。

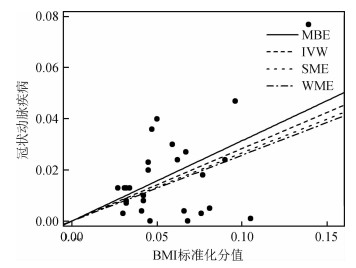

3.主分析结果:MBE显示SDS-BMI与CAD之间具有正向因果效应(OR=1.37,95%CI:1.09~1.72);即儿童BMI每增加1个标准差,其成年期患CAD的风险平均增加37%。见表 2。

4.敏感性分析结果:IVW、SME及WME法均得到了与MBE一致的结果,见表 2。提示在不同假设条件下,该因果效应具有稳健性,可以认为儿童肥胖与CAD间的因果效应得到了较为准确的估计。该结果进一步在图 1中证实,MBE得到的回归线和其他作为敏感性分析的MR分析(IVW、SME、WME)法得到的回归线基本一致,再次提示本研究结果的稳健性。

|

| 注:MBE:基于众数的方法;IVW:逆方差加权法;SME:简单中位数法;WME:加权中位数法 图 1 不同孟德尔随机化研究方法分析BMI标准化分值与冠状动脉疾病之间因果关系的散点图 |

首先,目前关于儿童肥胖对成年期患CAD的影响具有争议性:Sinaiko等[17]进行的纵向研究结果显示,儿童体重和BMI的增加与成年人胰岛素、血脂和收缩压水平显著相关,儿童体重超过正常范围可能是成年人心脏代谢疾病的危险因素,并强调了儿童肥胖对健康的不良影响;还有一些前瞻性研究发现儿童BMI与成年人心脏代谢疾病的发生有关[18-21]。然而,Lloyd等[22]却认为儿童肥胖与CAD发病风险之间不存在正向关联。本研究使用MR方法控制未知的混杂因素,提供了儿童肥胖与CAD发病风险呈现正相关的证据,发现儿童肥胖可能会增加CAD的发病风险。同时,由于遗传变异在个体的生命中是稳定存在的,儿童BMI本身就是因果暴露,因此本研究结果也提示儿童BMI升高可能导致CAD发病风险增加。

其次,先前已经有研究致力于探索降低儿童BMI的疗法:其中包含85个以干预学校的生活方式为主的RCT的Meta分析结果显示,干预后儿童BMI平均下降0.054 kg/m2[23];另有涵盖超过60个以干预肥胖儿童的生活方式为基础的RCT的Meta分析的结果显示,BMI的标准差评分的降低范围为-0.29~-0.63,而且对于<12岁儿童有更好的结果,这体现了对儿童肥胖早期干预的益处[24]。而根据本研究MR分析的结果,儿童BMI的下降可能会使成年期患CAD的风险降低12%,体现了预防儿童肥胖在降低CAD发病率方面的潜在重要性。

再次,本研究可能促进与儿童BMI相关的基因位点与儿童肥胖的发病机制研究并具有以下优势:一是大样本的GWAS使评估不同MR方法结果的稳健性成为可能,由此可以较为可靠地估计危险因素与疾病之间的因果效应;二是不同的MR方法得到一致的因果效应,可以证明研究结果的稳健性。

本研究存在局限性。一是本研究假设儿童BMI与CAD之间的关联是线性的,而有观察性研究显示出它们之间是非线性关联[25],因此,需要进一步研究对于非线性关联的疾病MR方法的选择和使用;二是尽管MR-Egger方法证明所选取的工具变量不受多效性的影响,但该结果可能只是反映了儿童BMI与心脏代谢疾病之间的共同遗传基础,而不是因果关系;三是影响儿童BMI的遗传变异也可能影响成年人BMI,因此很难确定这些影响何时发生;四是与儿童BMI相关的遗传变异与成年人BMI之间存在一定的交叉重叠;五是本研究并不能直接评估人口分层和其他潜在的混杂因素是否会影响研究结果,剩余和未测量的混杂因素可能依然存在。

总之,儿童肥胖与其成年期患CAD的风险具有因果关联,即儿童较高的BMI会导致其成年期患CAD的风险增加,MR分析结果提供了支持该因果关联的证据。鉴于近十几年儿童肥胖率的持续上升,该发现可能会对公共健康产生重大影响。然而,上述发现仍需在其他大样本或大规模、前瞻性观察性研究的MR研究中得到进一步的验证。

利益冲突 所有作者均声明不存在利益冲突

| [1] |

Benjamin EJ, Blaha MJ, Chiuve SE, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2017 update:a report from the American heart association[J]. Circulation, 2017, 135(10): e146-603. DOI:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000485 |

| [2] |

Anand SS, Bosch J, Eikelboom JW, et al. Rivaroxaban with or without aspirin in patients with stable peripheral or carotid artery disease:an international, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial[J]. Lancet, 2018, 391(10117): 219-229. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32409-1 |

| [3] |

Baker JL, Olsen LW, Sorensen TI. Childhood body-mass index and the risk of coronary heart disease in adulthood[J]. N Engl J Med, 2007, 357(23): 2329-2337. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa072515 |

| [4] |

Ajala O, Mold F, Boughton C, et al. Childhood predictors of cardiovascular disease in adulthood. A systematic review and Meta-analysis[J]. Obesity Rev, 2017, 18(9): 1061-1070. DOI:10.1111/obr.12561 |

| [5] |

Suglia SF, Koenen KC, Boynton-Jarrett R, et al. Childhood and adolescent adversity and cardio metabolic outcomes:a scientific statement from the American heart association[J]. Circulation, 2018, 137(5): e15-28. DOI:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000536 |

| [6] |

Smith GD, Ebrahim S. 'Mendelian randomization':can genetic epidemiology contribute to understanding environmental determinants of disease?[J]. Int J Epidemiol, 2003, 32(1): 1-22. DOI:10.1093/ije/dyg070 |

| [7] |

Lawlor DA, Harbord RM, Sterne JA, et al. Mendelian randomization:using genes as instruments for making causal inferences in epidemiology[J]. Stat Med, 2008, 27(8): 1133-1163. DOI:10.1002/sim.3034 |

| [8] |

Chen Y, Briesacher BA. Use of instrumental variable in prescription drug research with observational data:a systematic review[J]. J Clin Epidemiol, 2011, 64(6): 687-700. DOI:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.09.006 |

| [9] |

Dale CE, Fatemifar G, Palmer TM, et al. Causal associations of adiposity and body fat distribution with coronary heart disease, stroke subtypes, and type 2 diabetes mellitus:a Mendelian randomization analysis[J]. Circulation, 2017, 135(24): 2373-2388. DOI:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.026560 |

| [10] |

Felix JF, Bradfield JP, Monnereau C, et al. Genome-wide association analysis identifies three new susceptibility loci for childhood body mass index[J]. Human Mol Genet, 2016, 25(2): 389-403. DOI:10.1093/hmg/ddv472 |

| [11] |

Locke AE, Kahali B, Berndt SI, et al. Genetic studies of body mass index yield new insights for obesity biology[J]. Nature, 2015, 518(7538): 197-206. DOI:10.1038/nature14177 |

| [12] |

Nelson CP, Goel A, Butterworth AS, et al. Association analyses based on false discovery rate implicate new loci for coronary artery disease[J]. Nat Genet, 2017, 49(9): 1385-1391. DOI:10.1038/ng.3913 |

| [13] |

Bowden J, Smith GD, Burgess S. Mendelian randomization with invalid instruments:effect estimation and bias detection through Egger regression[J]. Int J Epidemiol, 2015, 44(2): 512-525. DOI:10.1093/ije/dyv080 |

| [14] |

Hartwig FP, Smith GD, Bowden J. Robust inference in summary data Mendelian randomization via the zero modal pleiotropy assumption[J]. Int J Epidemiol, 2017, 46(6): 1985-1998. DOI:10.1093/ije/dyx102 |

| [15] |

Burgess S, Butterworth A, Thompson SG. Mendelian randomization analysis with multiple genetic variants using summarized data[J]. Genet Epidemiol, 2013, 37(7): 658-665. DOI:10.1002/gepi.21758 |

| [16] |

Yavorska OO, Burgess S. Mendelian Randomization:an R package for performing MENDELIAN randomization analyses using summarized data[J]. Int J Epidemiol, 2017, 46(6): 1734-1739. DOI:10.1093/ije/dyx034 |

| [17] |

Sinaiko AR, Donahue RP, Jacobs DR Jr, et al. Relation of weight and rate of increase in weight during childhood and adolescence to body size, blood pressure, fasting insulin, and lipids in young adults. The minneapolis children's blood pressure study[J]. Circulation, 1999, 99(11): 1471-1476. DOI:10.1161/01.cir.99.11.1471 |

| [18] |

Zhang T, Zhang HJ, Li Y, et al. Temporal relationship between childhood body mass index and insulin and its impact on adult hypertension:the Bogalusa heart study[J]. Hypertension, 2016, 68(3): 818-823. DOI:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.116.07991 |

| [19] |

Park MH, Falconer C, Viner RM, et al. The impact of childhood obesity on morbidity and mortality in adulthood:a systematic review[J]. Obesity Rev, 2012, 13(11): 985-1000. DOI:10.1007/s11892-018-1062-9 |

| [20] |

Reilly JJ, Kelly J. Long-term impact of overweight and obesity in childhood and adolescence on morbidity and premature mortality in adulthood:systematic review[J]. Int J Obes, 2011, 35(7): 891-898. DOI:10.1038/ijo.2010.222 |

| [21] |

Zhang HJ, Zhang T, Li SX, et al. Long-term excessive body weight and adult left ventricular hypertrophy are linked through later-life body size and blood pressure:the Bogalusa heart study[J]. Circ Res, 2017, 120(10): 1614-1621. DOI:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.310421 |

| [22] |

Lloyd LJ, Langley-Evans SC, Mcmullen S. Childhood obesity and risk of the adult Metabolic syndrome:a systematic review[J]. Int J Obes, 2012, 36(1): 1-11. DOI:10.1038/ijo.2011.186 |

| [23] |

Oosterhoff M, Joore M, Ferreira I. The effects of school-based lifestyle interventions on body mass index and blood pressure:a multivariate multilevel Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials[J]. Obes Rev, 2016, 17(11): 1131-1153. DOI:10.1111/obr.12446 |

| [24] |

Oude Luttikhuis H, Baur L, Jansen H, et al. Interventions for treating obesity in children[J]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2009(1): Cd001872. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD001872.pub2 |

| [25] |

Gunnell DJ, Frankel SJ, Nanchahal K, et al. Childhood obesity and adult cardiovascular mortality:a 57-y follow-up study based on the Boyd Orr cohort[J]. Am J Clin Nutr, 1998, 67(6): 1111-1118. DOI:10.1093/ajcn/67.6.1111 |

2019, Vol. 40

2019, Vol. 40