文章信息

- 黄慧瑶, 朱松林, 周天虹, 李志芳, 刘成成, 王红, 颜仕鹏, 宋述铭, 邹霜梅, 张月明, 李宁, 朱琳, 廖先珍, 石菊芳, 代敏.

- Huang Huiyao, Zhu Songlin, Zhou Tianhong, Li Zhifang, Liu Chengcheng, Wang Hong, Yan Shipeng, Song Shuming, Zou Shuangmei, Zhang Yueming, Li Ning, Zhu Lin, Liao Xianzhen, Shi Jufang, Dai Min.

- 全球结直肠癌疾病自然史转归参数的Meta分析

- Natural history of colorectal cancer:a Meta-analysis on global prospective cohort studies

- 中华流行病学杂志, 2019, 40(7): 821-831

- Chinese journal of Epidemiology, 2019, 40(7): 821-831

- http://dx.doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2019.07.017

-

文章历史

收稿日期: 2018-12-19

2. 湖南省肿瘤医院肿瘤防治研究办公室, 长沙 410006;

3. 新疆医科大学附属肿瘤医院肿瘤防治研究办公室, 乌鲁木齐 830011;

4. 开滦总医院肿瘤科, 唐山 063000;

5. 国家癌症中心/国家肿瘤临床医学研究中心/中国医学科学院北京协和医学院肿瘤医院癌症早诊早治办公室, 北京 100021;

6. 国家癌症中心/国家肿瘤临床医学研究中心/中国医学科学院北京协和医学院肿瘤医院病理科, 北京 100021;

7. 国家癌症中心/国家肿瘤临床医学研究中心/中国医学科学院北京协和医学院肿瘤医院腔镜科, 北京 100021

2. Office for Cancer Control and Research, Hunan Cancer Hospital, Changsha 410006, China;

3. Teaching and Research Department, Affiliated Cancer Hospital of Xinjiang Medical University, Urumqi 830011, China;

4. Medical Oncology, Health Center for Staff in Kailuan Hospital, Tangshan 063000, China;

5. Office of Cancer Screening, National Cancer Center/National Clinical Research Center for Cancer/Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing 100021, China;

6. Department of Pathology, National Cancer Center/National Clinical Research Center for Cancer/Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing 100021, China;

7. Department of Endoscopy, National Cancer Center/National Clinical Research Center for Cancer/Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing 100021, China

我国结直肠癌发病和死亡呈现增长趋势,结直肠癌患病给癌症患者造成身体、心理和经济等多重压力[1-3]。全肠镜和乙状结肠镜筛查均可有效降低危害全球健康的结直肠癌死亡率[4]。构建我国人群特异性的结直肠癌自然史模型以及获得足够的疾病转归参数,是进行最优化结直肠癌筛查方案选择和实现节约社会资源目标的前提条件[5]。基于全球结直肠癌疾病自然史模型研究[6],团队前期已提出我国人群特异性结直肠癌自然史模型结构框架,并获得基于模型的相关自然史参数。通常认为针对同质人群的大样本长期筛查随访数据是构建模型的最佳参数来源,不可获得时可引用非同质人群相关研究数据或者已有模型数据[7]。本研究汇总全球范围内结直肠癌自然史队列研究,掌握根据内镜结果明确基线健康状态人群的结直肠癌疾病自然史转归参数可获得性,进行Meta分析并比较各健康状态人群发展为结直肠不同疾病状态的1年转归概率,为构建我国人群特异性结直肠癌模型提供数据支持,也为国内外结直肠癌筛查人群监测策略制定提供基于随访研究Meta分析的高质量证据。

资料与方法1.文献检索:基于PubMed、Embase、Cochrane和中国生物医学文献数据库(CBM),进行全球范围内基于队列研究的结直肠癌疾病自然史研究。检索日期截至2017年3月,英文检索式以“Colon”、“Rectum*”、“Adenoma”、“Polyps”、“Endoscopy,Digestive System”、“Natural History”、“Cohort Studies”、“Follow-up studies”和“Mass Screening”等为Mesh主题词,并与“colorect*”、“serrated adenoma*”和“endoscop*”等自由词结合,限定语种为英文、研究对象为人类;中文检索式以“结直肠”、“结肠”、“直肠”、“腺瘤”、“锯齿状病变”、“息肉”、“自然史”、“队列”、“随访”、“内镜”、“肠镜”和“乙状结肠镜”等进行检索。

2.纳入及排除标准:纳入标准:①结直肠癌疾病自然史随访研究;②疾病诊断明确,有基线和结局内镜检查病理结果。排除标准:①现况研究,如横断面和病例对照研究等;②特殊人群研究,包括军人、囚犯、有过癌症史、家族遗传性息肉病和结直肠炎性疾病等;③基于医院的单纯腺瘤患者术后随访研究;④未报告任何转归参数或相关原始数据;⑤综述、个案报道、摘要及重复发表研究;⑥动物研究和分子水平研究。

3.数据摘录和质量评价:2名研究人员独立平行进行数据提取和质量评价工作,意见不一致时,咨询第三方专家。数据摘录分3个部分:①基本信息,包括第一作者、发表年份、基线年龄、队列类型、随访时间、随访率、基线和结局病理诊断技术以及结局病理诊断医生人数;②结直肠健康状态分类体系(包括病变路径、腺瘤和癌症分类系统)和基线不同健康状态人群转归参数可获得性;③各转归参数计算所需原始数据,包括随访人数、随访时间和结局事件发生例数。

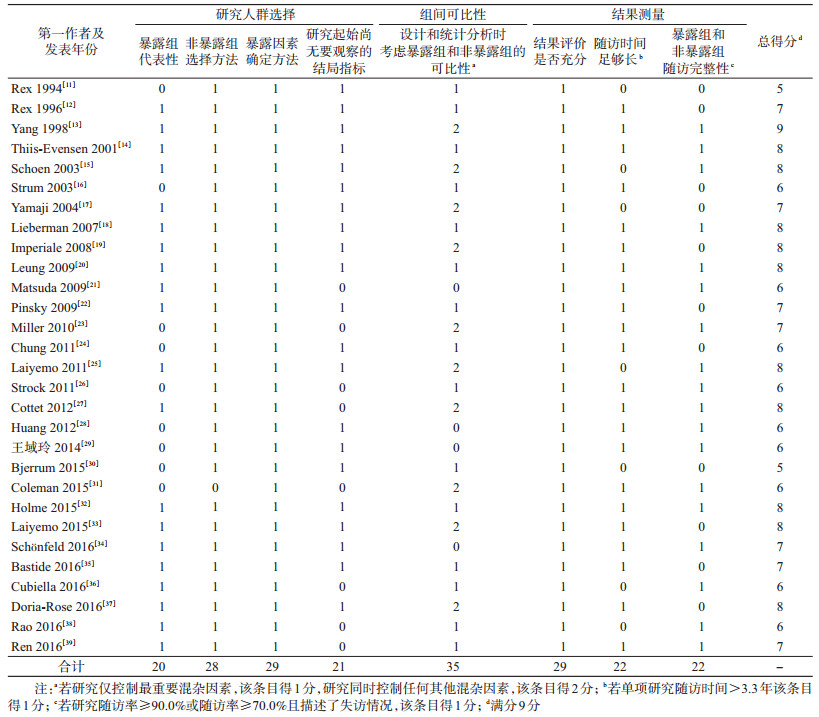

本研究采用适用于队列研究的NOS(Newcastle-Ottawa Scale)量表进行文献质量评价[8]。该量表涵盖以下3个方面8个条目:①研究人群选择:包括暴露组的代表性,非暴露组的选择方法,暴露因素的确定方法和研究起始时尚无要观察的结局指标4个条目,4分;②组间可比性:设计和统计分析时考虑暴露组和非暴露组的可比性1个条目,2分;③结果测量:包括结果评价是否充分、随访时间足够长以及暴露组和非暴露组随访完整性3个条目,3分。本综述采用国际通用评价标准[9],若研究随访时间大于本综述所有纳入研究随访时间的P25,则“随访时间足够长”条目得1分;若研究随访率≥90.0%或者随访率≥70.0%且描述了失访情况,则“暴露组和非暴露组随访完整性”条目得1分。满分9分,总得分≥6分认为质量较高,4~5分质量一般,≤3分质量较低,得分越高,质量越好。

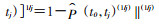

4.数据处理和统计分析:根据摘录数据,首先计算单项研究多年累积发病率,再使用寿命表法折算获得1年转归概率[10]。计算公式

使用Stata 12.1软件进行Meta分析。采用随机效应模型对研究数量>3项的转归参数进行Meta合并和敏感性分析,主要结果指标包括健康人群(基线内镜结果阴性)和不同分类腺瘤切除后的转归参数,合并效应值用1年转归概率(95%CI)表示。Q检验所得I2≥50.0%为纳入研究存在异质性,秩相关检验(Begg ’s检验)用于评价发表偏倚。以P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。

结果1.检索结果:4个数据库共检索到相关文献5 119篇。根据制定的纳入排除标准,阅读题目和摘要后剔除4 656篇,全文阅读初筛纳入463篇文献,最终纳入29篇文献,中文1篇,其余为英文[11-39]。见图 1。

|

| 图 1 文献检索流程图 |

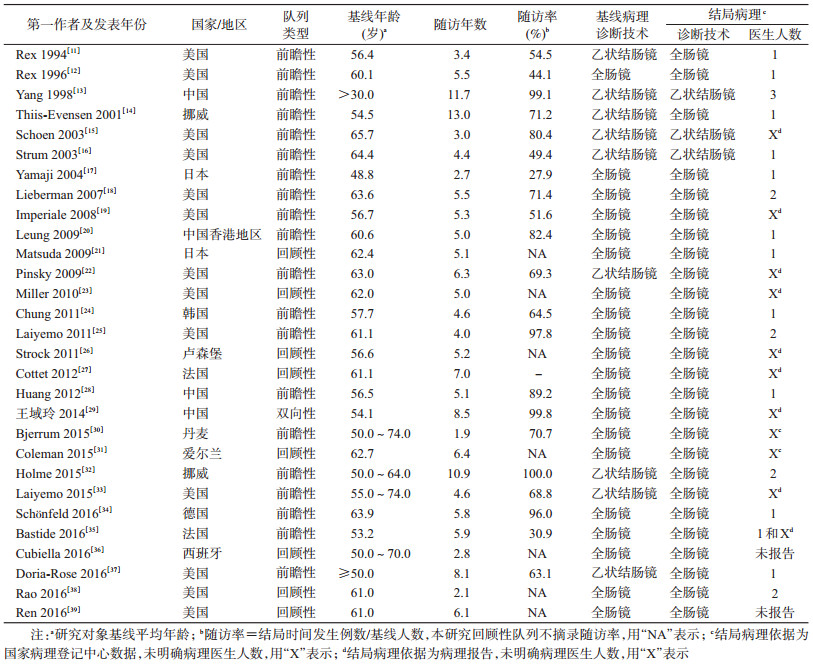

2.纳入研究基本信息:纳入29项均为队列研究,一半以上发表于近5年(15项),平均随访时间5.7年,随访M(P25~P75)为5.2(4.4~6.3)年。研究对象以美国人群最多(13项),其次是中国人群(4项),基线平均年龄范围为48.8~65.7岁。其中有20项为前瞻性队列,其随访率M(P25~P75)为70.7%(54.5%~89.2%)。病理诊断技术多采用全肠镜(基线19项、结局25项),部分采用乙状结肠镜;结局病理诊断多基于研究现场病理医生(17项),其次为已有病理报告和国家病理登记中心数据(11项)。见表 1。

3.纳入研究质量评价:基于NOS量表的文献质量评价结果显示,纳入研究总体质量较高(27项≥6分);问题相对较为突出条目包括暴露组代表性有限(9项)、回顾性队列研究起始时已出现要观察的结局指标(8项)、组间可比性有限(19项)、随访时间不够长(7项)以及暴露组和非暴露组随访不完整(7项)。见表 2。

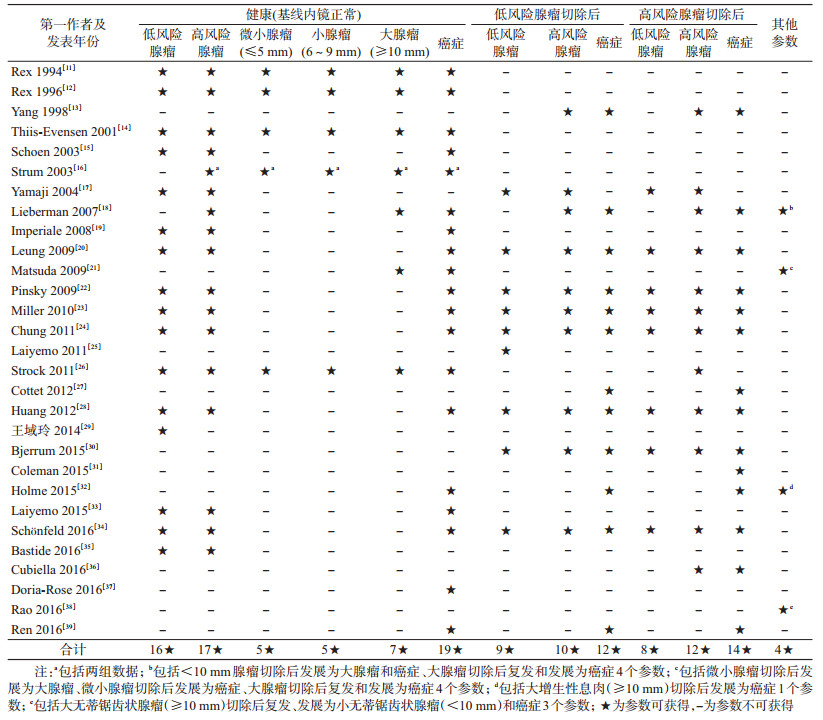

4.疾病自然史转归参数可获得性:纳入研究主要关注经典“腺瘤-癌”路径(28项),仅2项研究报告了锯齿状病变路径参数,见表 3。

(1)“腺瘤-癌”路径:28项研究报告基于腺瘤风险分类结果,分别有5项和1项报告腺瘤直径大小三分类(≤5、6~9和≥10 mm)和二分类(<10和≥10 mm)结果。不同基线健康状态人群各转归参数涉及的研究数量、合计随访人数以及不同分期癌症发病结果分述如下:①基线健康人群6个转归参数:发展为低风险腺瘤(16项,58 235)、高风险腺瘤(17项,62 089)、微小腺瘤(<5 mm,4项,1 277)、小腺瘤(6~9 mm,4项,1 277)、大腺瘤(≥10 mm,7项,3 531)和癌症(19项,104 836);仅1项研究报告基于病灶范围分期系统的癌症发病数据[36],从基线健康发展为局限性、区域性和转移性癌的1年转归概率分别为0.000 4、0.000 5和0.000 3。②低风险腺瘤切除后人群3个转归参数:复发(9项,4 788)、发展为高风险腺瘤(10项,5 736)和癌症(12项,11 347);未见不同临床分期癌症发病数据报告。③高风险腺瘤切除后人群3个参数:复发(12项,7 030)、发展为低风险腺瘤(8项,2 489)和癌症(14项,14 899);仅1项研究报告基于TNM分期系统的癌症发病数据[35],且相关参数不完整。④其他参数:微小腺瘤切除后发展为大腺瘤和癌症(均为1项,1 655)、小腺瘤切除后发展为大腺瘤和癌症(均为1项,1 123)、大腺瘤切除后复发和发展为癌症(均为2项,648)和<10 mm腺瘤切除后发展为大腺瘤和癌症(均为1项,622)。

(2)锯齿状病变路径:该路径主要包括无蒂锯齿状腺瘤(sessile serrated adenomas,SSA)和增生性息肉(hyperplastic polyps,HP),以10 mm为界可分别细分为大SSA、小SSA和大HP、小HP。纳入的2项锯齿状病变路径研究,分别报告大HP切除后变为癌症[32]、大SSA复发[38]、变为小SSA[38]和癌症4个参数,对应1年转归概率分别为0.003 5、0.006 8、0.010 3和0。

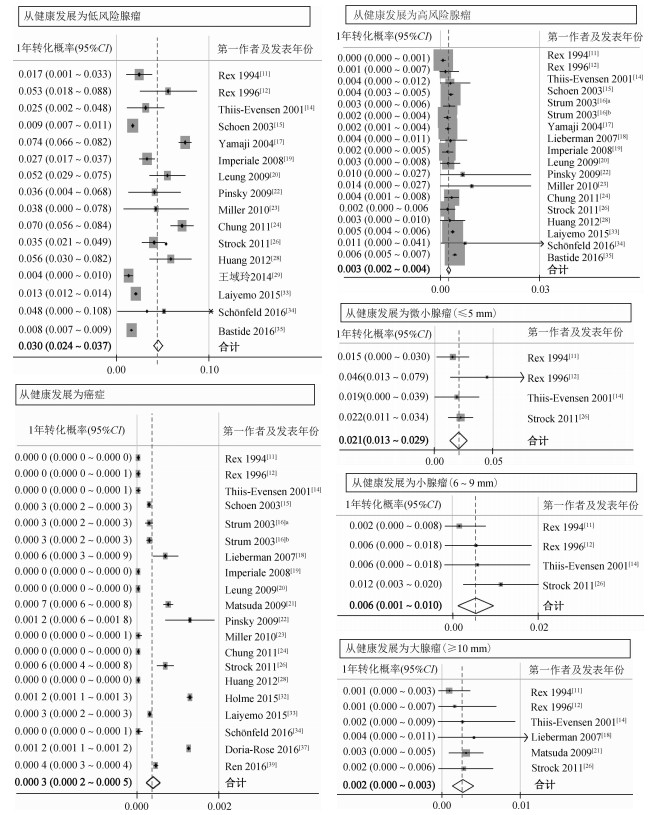

5.转归参数Meta分析结果:对研究数量>3篇的9个转归参数分别进行Meta分析和敏感性分析,计算1年转归概率及其95%CI。

(1)基线健康人群:健康发展为低风险腺瘤、微小腺瘤、小腺瘤、高风险腺瘤、大腺瘤和癌症的1年转归概率依次降低,分别为0.030(0.024~0.037)、0.021(0.013~0.029)、0.006(0.001~0.010)、0.003(0.002~0.004)、0.002(0.000~0.003)和0.000 3(0.000 2~0.000 5)。Q检验提示健康发展为微小、小和大腺瘤这3个转归参数不存在异质性(所有P>0.05,I2分别为0.0%、6.1%和0.0%),另外3个参数存在异质性(所有P<0.05,I2>50.0%)。见图 2。

(2)低风险腺瘤切除后人群:低风险腺瘤切除后复发、进展为高风险腺瘤和癌症的1年转归概率依次降低,分别为0.109(0.062~0.157)、0.009(0.004~0.013)和0.000 6(0.000 4~0.000 8)。Q检验结果提示这3个参数均存在异质性(所有P<0.05,I2>50.0%)。见图 3。

|

| 图 3 低风险和高风险腺瘤切除后的疾病自然史进展参数汇总 |

(3)高风险腺瘤切除后人群:高风险腺瘤切除后发展为低风险腺瘤、复发和发展为癌症的1年转归概率依次降低,分别为0.133(0.081~0.185)、0.038(0.028~0.048)和0.002(0.001~0.003)。Q检验结果提示这3个参数均存在异质性(所有P<0.05,I2>50.0%)。敏感性分析显示这3个参数结果均稳健。见图 3。

6.发表偏倚和敏感性分析:Begg’s检验结果提示,健康到癌症(P=0.04)和低风险腺瘤切除后发展为癌症(P=0.01)2个参数可能存在发表偏倚,其他10个参数不存在发表偏倚。各参数敏感性分析结果提示,健康到微小腺瘤在剔除1项研究时变为0.022(0.017~0.027)[16],其他参数结果均稳健。

讨论对结直肠癌疾病自然史随访研究汇总发现,全球已有29项研究报道;转归参数可获得性及其健康状态分类系统汇总结果一方面支持我国人群特异性结直肠癌自然史模型结构框架[6],即同时考虑“腺瘤-癌”和锯齿状病变两条路径、癌前病变以腺瘤为主并优先考虑基于腺瘤风险分类;另一方面,也提示模型构建工作面临锯齿状病变路径以及“腺瘤-癌”路径不同分期癌症发病数据匮乏的挑战。基线不同健康状态人群(健康、低风险切除后和高风险腺瘤切除后)系列参数,补充了接受过早期诊断和治疗人群的结直肠癌疾病转归情况,可用于结直肠癌干预模型的效果评价;也为全球结直肠癌筛查人群监测策略制定提供基于原创队列研究Meta分析的高质量证据。

将本研究基于队列研究Meta结果与团队前期基于模型研究结果进行对比[6]。同一参数本研究结果更高(包括正常到低风险腺瘤:0.016 vs. 0.030;正常到微小腺瘤:0.13 vs. 0.021)。一方面,本研究健康人群源于基线内镜筛查阴性人群,而通常进入内镜筛查人群多为初筛结果阳性者,其发病风险可能高于模型定义的健康人群;另一方面,本研究结果基于Meta分析,模型研究简单采用中位数表示;建议后期模型构建视人群而定,高危人群优先考虑队列结果,全人群优先模型结果。与给予任何干预相比,腺瘤切除后癌症发病率显著下降;其中,低风险腺瘤切除后下降一半(0.009 vs. 0.020),高风险腺瘤切除后癌症发病率是不切除时的1/22(0.002 vs. 0.044);提示癌症早诊早治对于降低结直肠癌发病率这一重大公共卫生意义。

全球范围内已有综述基于随访研究进行结直肠癌自然史转归参数汇总[40-42],但存在以下几个问题:①仅关注“腺瘤-癌”路径;②多基于医院腺瘤术后患者随访数据,存在高估转归参数的可能;③综合评价指标均为累积发病率,平均累积时间长短不一(2~4年),无法直接比较。本研究同时关注两条病变路径,汇总基于筛查监测人群随访研究的“腺瘤-癌”路径参数,同时汇总基于医院锯齿状病变患者术后随访研究(因未见筛查监测人群随访研究的“锯齿状病变”路径参数报告),并以1年转归概率为综合评价指标进行结果报告。下面将从研究结果本身以及相关启示两个方面进行讨论。

Meta结果表明低风险腺瘤切除后人群癌症平均发病概率是健康人群2倍,大小为0.000 6和0.000 3;2014年基于7项随访研究的Meta结果两者发病概率差异更明显,倍数关系为4.5,大小为0.000 34和0.000 08[41];与Hassan等[41]综述比较,本研究具有纳入最新研究、文献数量翻倍和样本量提高数倍等优势,保证了本综述研究结果的可靠性和稳定性。Martinez等[40]发现低风险腺瘤切除后人群癌症平均发病概率为0.001 2,高于本研究和Hassan等[41]的研究结果,可能与研究对象不是筛查监测人群,而是医院腺瘤术后患者有关。与低风险腺瘤切除后人群相比,高风险腺瘤切除后人群癌症发病概率又提高2倍,平均大小为0.002,近似于Martinez等[40]基于医院腺瘤术后患者研究结果。

从结直肠癌自然史发展角度看,上述3类人群癌症发病概率差异与其发展为高风险和低风险腺瘤的发病概率密切相关。首先高风险腺瘤发病概率,高风险腺瘤切除后人群是低风险切除后人群的4.2倍、是健康人群的12.7倍,平均发病概率分别为0.038、0.009和0.003;其次低风险腺瘤发病概率,高风险腺瘤切除后人群是低风险切除后人群的1.2倍、是健康人群的4.4倍,平均发病概率分别为0.133、0.109和0.030。Martinez等[40]研究中低风险腺瘤发病概率与本研究较为接近,但高风险腺瘤发病概率较高,可能与研究基于医院腺瘤术后患者有关。基线健康进展到高风险腺瘤的发病概率较Hassan等[41]研究结果0.004偏低。本研究从健康到微小腺瘤(0.021)和小腺瘤(0.006)的发病概率之和与健康到低风险腺瘤接近,健康到大腺瘤的平均发病概率(0.002)为健康到高风险腺瘤的2/3,结果大小与腺瘤风险分类定义相较吻合[43]。

相对而言,基于模型研究[6]和基于随访研究的结直肠“腺瘤-癌”路径自然史参数可获得性均较好;基于锯齿状病变路径的相关参数十分有限,分别有1项模型研究和2项队列研究报告了相关参数,后期模型构建可参考国外模型参数进行假设。已知15%~20%结直肠癌源于锯齿状病变路径[44],锯齿状病变近年来引起了国内外结直肠癌筛查的普遍重视。2014年《中国早期结直肠癌及癌前病变筛查及诊治共识意见》(《筛查共识意见》)明确将锯齿状病变列为结直肠癌癌前病变[45]。基于有限的低级别证据,美国最新息肉监测指南[43],首次提出对锯齿状病变(仅针对大SSA和伴有异型增生的SSA)进行3年1次监测随访。

基于团队前期模型研究提出的我国人群特异性结直肠癌自然史模型结构,结合本研究所得相关参数可获得性及结果大小,我们获得诸多启示。一方面,我国分期癌症转归数据匮乏,在我国开展更多高质量研究,掌握锯齿状病变癌症发病数据和筛查监测人群不同分期癌症发病数据,基于此制定适宜癌症筛查和随访策略,对国内外结直肠癌防控至关重要[46]。另一方面,在全球缺乏临床试验或Meta等高级别证据前提下[43],本研究基于随访研究Meta证据表明高风险腺瘤切除后3年累积发病率和低风险腺瘤切除后10年累积发病率均为0.006,我们认为美国指南以及我国的《筛查共识意见》中以基线内镜结果作为结直肠癌发病风险分层依据,推荐低风险和高风险腺瘤切除后进行5~10年1次和3年1次随访是合理的。

除了上文提到的本研究覆盖结直肠癌两条病变路径相关参数、采用1年转归概率这一可比指标等优点外,本研究还有文献检索较全面、对结果评价较为充分以及随访时间较已有研究长等优点。

本研究存在局限性。尽管纳入文献质量较高、敏感性分析结果稳定,但多个转归参数纳入研究间异质性较大,可能与研究对象有别以及肠镜检查质量参差不齐等有关。本研究转归参数多基于国外队列研究结果,可能与中国人群疾病转归概率存在差异。另外,为保证结果与已有报道可比,本研究采用1年转归概率作为评价指标,但纳入研究随访时间不同,发病密度结果可能更准确。

我国人群特异性的结直肠癌疾病自然史模型框架及主要转归参数基本就绪,构建可用于我国结直肠癌筛查方案最优化选择的评价工具是接下来工作和研究的重点。在此基础上,参考和借鉴国际已有模型的评价方法和评价指标体系[47],进一步评估中国结直肠癌筛查的成本效果和预算影响。开展高质量随访和临床试验研究,获得完备的锯齿状病变路径转归参数和不同TNM分期癌症发病数据也是全球研究的重要方向之一。

利益冲突 所有作者均声明不存在利益冲突

志谢 感谢岳馨培(郑州大学第一附属医院病案管理科)和郭兰伟(河南省肿瘤医院肿瘤防治研究办公室)对数据处理分析提供的宝贵意见;感谢王乐和朱娟(国家癌症中心/中国医学科学院北京协和医学院肿瘤医院早诊早治办公室)对稿件撰写提供的宝贵意见

| [1] |

张玥, 石菊芳, 黄慧瑶, 等. 中国人群结直肠癌疾病负担分析[J]. 中华流行病学杂志, 2015, 36(7): 709-714. Zhang Y, Shi JF, Huang HY, et al. Burden of colorectal cancer in China[J]. Chin J Epidemiol, 2015, 36(7): 709-714. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2015.07.010 |

| [2] |

Huang HY, Shi JF, Guo LW, et al. Expenditure and financial burden for the diagnosis and treatment of colorectal cancer in China:a hospital-based, multicenter, cross-sectional survey[J]. Chin J Cancer, 2017, 36: 41. DOI:10.1186/s40880-017-0209-4 |

| [3] |

Guo LW, Huang HY, Shi JF, et al. Medical expenditure for esophageal cancer in China:a 10-year multicenter retrospective survey (2002-2011)[J]. Chin J Cancer, 2017, 36: 73. DOI:10.1186/s40880-017-0242-3 |

| [4] |

Cruzado J, Sánchez FI, Abellán JM, et al. Economic evaluation of colorectal cancer (CRC) screening[J]. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol, 2013, 27(6): 867-880. DOI:10.1016/j.bpg.2013.09.004 |

| [5] |

Gulliford MC, Bhattarai N, Charlton J, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a universal strategy of brief dietary intervention for primary prevention in primary care:population-based cohort study and Markov model[J]. Cost Eff Resour Alloc, 2014, 12: 4. DOI:10.1186/1478-7547-12-4 |

| [6] |

李志芳, 黄慧瑶, 石菊芳, 等. 结直肠癌疾病自然史模型研究的系统综述:体系分类、参数分析及推荐构建我国人群特异性模型[J]. 中华流行病学杂志, 2017, 38(2): 253-260. Li ZF, Huang HY, Shi JF, et al. A systematic review of worldwide natural history models of colorectal cancer:classification, transition rate and a recommendation for developing Chinese population-specific model[J]. Chin J Epidemiol, 2017, 38(2): 253-260. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2017.02.024 |

| [7] |

Greuter MJS, Xu XM, Lew JB, et al. Modeling the adenoma and serrated pathway to Colorectal Cancer (ASCCA)[J]. Risk Anal, 2014, 34(5): 889-910. DOI:10.1111/risa.12137 |

| [8] |

曾宪涛, 刘慧, 陈曦, 等. Meta分析系列之四:观察性研究的质量评价工具[J]. 中国循证心血管医学杂志, 2012, 4(4): 297-299. Zeng XT, Liu H, Chen X, et al. Meta analysis series 4:quality assessment tools for observational study[J]. Chin J Evid Based Cardiovasc Med, 2012, 4(4): 297-299. DOI:10.3969/j.1674-4055.2012.04.004 |

| [9] |

Wells G, Shea B, O'Connell D, et al. New Castle-ottawa quality assessment scale cohort studies[EB/OL]. (2012-06-15)[2018-12-01].http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/nosgen.pdf.

|

| [10] |

Miller DK, Homan SM. Determining transition probabilities:confusion and suggestions[J]. Med Decis Making, 1994, 14(1): 52-58. DOI:10.1177/0272989X9401400107 |

| [11] |

Rex DK, Lehman GA, Ulbright TM, et al. The yield of a second screening flexible sigmoidoscopy in average-risk persons after one negative examination[J]. Gastroenterology, 1994, 106(3): 593-595. DOI:10.1016/0016-5085(94)90690-4 |

| [12] |

Rex DK, Cummings OW, Helper DJ, et al. 5-year incidence of adenomas after negative colonoscopy in asymptomatic average-risk persons[see comment][J]. Gastroenterology, 1996, 111(5): 1178-1181. DOI:10.1053/gast.1996.v111.pm8898630 |

| [13] |

Yang G, Yu H, Zheng W, et al. Pathologic features of initial adenomas as predictors for metachronous adenomas of the rectum[J]. J Natl Cancer Inst, 1998, 90(21): 1661-1665. DOI:10.1093/jnci/90.21.1661 |

| [14] |

Thiis-Evensen E, Hoff GS, Sauar J, et al. The effect of attending a flexible sigmoidoscopic screening program on the prevalence of colorectal adenomas at 13-year follow-up[J]. Am J Gastroenterol, 2001, 96(6): 1901-1907. DOI:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03891 |

| [15] |

Schoen RE, Pinsky PF, Weissfeld JL, et al. Results of repeat sigmoidoscopy 3 years after a negative examination[J]. JAMA, 2003, 290(1): 41-48. |

| [16] |

Strum WB. Incidence of advanced adenomas of the rectosigmoid colon three years and five years after negative flexible sigmoidoscopy in 4010 patients[J]. Dig Dis Sci, 2003, 48(12): 2278-2283. DOI:10.1023/b:ddas.0000007863.43273.0b |

| [17] |

Yamaji Y, Mitsushima T, Ikuma H, et al. Incidence and recurrence rates of colorectal adenomas estimated by annually repeated colonoscopies on asymptomatic Japanese[J]. Gut, 2004, 53(4): 568-572. DOI:10.1136/gut.2003.026112 |

| [18] |

Lieberman DA, Weiss DG, Harford WV, et al. Five-year colon surveillance after screening colonoscopy[J]. Gastroenterology, 2007, 133(4): 1077-1085. DOI:10.1053/j.gastro.2007.07.006 |

| [19] |

Imperiale TF, Glowinski EA, Lin-Cooper C, et al. Five-year risk of colorectal neoplasia after negative screening colonoscopy[J]. N Engl J Med, 2008, 359(12): 1218-1224. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa0803597 |

| [20] |

Leung WK, Lau JY, Suen BY, et al. Repeat-screening colonoscopy 5 years after normal baseline-screening colonoscopy in average-risk Chinese:a prospective study[J]. Am J Gastroenterol, 2009, 104(8): 2028-2034. DOI:10.1038/ajg.2009.202 |

| [21] |

Matsuda T, Fujii T, Sano Y, et al. Five-year incidence of advanced neoplasia after initial colonoscopy in Japan:a multicenter retrospective cohort study[J]. Jpn J Clin Oncol, 2009, 39(7): 435-442. DOI:10.1093/jjco/hyp047 |

| [22] |

Pinsky PF, Schoen RE, Weissfeld JL, et al. The yield of surveillance colonoscopy by adenoma history and time to examination[J]. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2009, 7(1): 86-92. DOI:10.1016/j.cgh.2008.07.014 |

| [23] |

Miller HL, Mukherjee R, Tian JM, et al. Colonoscopy surveillance after polypectomy may be extended beyond five years[J]. J Clin Gastroenterol, 2010, 44(8): e162-166. DOI:10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181e5cd22 |

| [24] |

Chung SJ, Kim YS, Yang SY, et al. Five-year risk for advanced colorectal neoplasia after initial colonoscopy according to the baseline risk stratification:a prospective study in 2452 asymptomatic Koreans[J]. Gut, 2011, 60(11): 1537-1543. DOI:10.1136/gut.2010.232876 |

| [25] |

Laiyemo AO, Doubeni C, Sanderson II AK, et al. Likelihood of missed and recurrent adenomas in the proximal versus the distal colon[J]. Gastrointest Endosc, 2011, 74(2): 253-261. DOI:10.1016/j.gie.2011.02.023 |

| [26] |

Strock P, Mossong J, Scheiden R, et al. Colorectal cancer incidence is low in patients following a colonoscopy[J]. Dig Liver Dis, 2011, 43(11): 899-904. DOI:10.1016/j.dld.2011.05.020 |

| [27] |

Cottet V, Jooste V, Fournel I, et al. Long-term risk of colorectal cancer after adenoma removal:a population-based cohort study[J]. Gut, 2012, 61(8): 1180-1186. DOI:10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300295 |

| [28] |

Huang YL, Li XH, Wang ZY, et al. Five-year risk of colorectal neoplasia after normal baseline colonoscopy in asymptomatic Chinese Mongolian over 50 years of age[J]. Int J Colorectal Dis, 2012, 27(12): 1651-1656. DOI:10.1007/s00384-012-1516-5 |

| [29] |

王域玲, 于恩达, 钱维, 等. 初查结肠镜阴性人群结直肠肿瘤发生风险研究[J]. 国际肿瘤学杂志, 2014, 41(2): 150-154. Wang YL, Yu ED, Qian W, et al. Risk of colorectal tumor after negative baseline screening colonoscopy[J]. J Int Oncol, 2014, 41(2): 150-154. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1673-422X.2014.02.021 |

| [30] |

Bjerrum A, Milter MC, Andersen O, et al. Risk stratification and detection of new colorectal neoplasms after colorectal cancer screening with faecal occult blood test:experiences from a Danish screening cohort[J]. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2015, 27(12): 1433-1437. DOI:10.1097/MEG.0000000000000451 |

| [31] |

Coleman HG, Loughrey MB, Murray LJ, et al. Colorectal cancer risk following adenoma removal:a large prospective population-based cohort study[J]. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 2015, 24(9): 1373-1380. DOI:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0085 |

| [32] |

Holme Ø, Bretthauer M, Eide TJ, et al. Long-term risk of colorectal cancer in individuals with serrated polyps[J]. Gut, 2015, 64(6): 929-936. DOI:10.1136/gutjnl-2014-307793 |

| [33] |

Laiyemo AO, Doubeni C, Pinsky PF, et al. Occurrence of distal colorectal neoplasia among whites and blacks following negative flexible sigmoidoscopy:an analysis of PLCO Trial[J]. J Gen Intern Med, 2015, 30(10): 1447-1453. DOI:10.1007/s11606-015-3297-3 |

| [34] |

Schönfeld VJ, Müller-Steden B. Screening colonoscopy and colorectal cancer:a single center long term study[J]. Z Gastroenterol, 2016, 54(4): 312-315. DOI:10.1055/s-0041-110808 |

| [35] |

Bastide N, Morois S, Cadeau C, et al. Heme iron intake, dietary antioxidant capacity, and risk of colorectal adenomas in a large cohort study of French women[J]. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 2016, 25(4): 640-647. DOI:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0724 |

| [36] |

Cubiella J, Carballo F, Portillo I, et al. Incidence of advanced neoplasia during surveillance in high-and intermediate-risk groups of the European colorectal cancer screening guidelines[J]. Endoscopy, 2016, 48(11): 995-1002. DOI:10.1055/s-0042-112571 |

| [37] |

Doria-Rose VP, Levin TR, Palitz A, et al. Ten-year incidence of colorectal cancer following a negative screening sigmoidoscopy:an update from the Colorectal Cancer Prevention (CoCaP) programme[J]. Gut, 2016, 65(2): 271-277. DOI:10.1136/gutjnl-2014-307729 |

| [38] |

Rao AK, Soetikno R, Raju GS, et al. Large sessile serrated polyps can be safely and effectively removed by endoscopic mucosal resection[J]. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2016, 14(4): 568-574. DOI:10.1016/j.cgh.2015.10.013 |

| [39] |

Ren JM, Kirkness CS, Kim M, et al. Long-term risk of colorectal cancer by gender after positive colonoscopy:population-based cohort study[J]. Curr Med Res Opin, 2016, 32(8): 1367-1374. DOI:10.1080/03007995.2016.1174840 |

| [40] |

Martinez ME, Baron JA, Lieberman DA, et al. A pooled analysis of advanced colorectal neoplasia diagnoses after colonoscopic polypectomy[J]. Gastroenterology, 2009, 136(3): 832-841. DOI:10.1053/j.gastro.2008.12.007 |

| [41] |

Hassan C, Gimeno-García A, Kalager M, et al. Systematic review with Meta-analysis:the incidence of advanced neoplasia after polypectomy in patients with and without low-risk adenomas[J]. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 2014, 39(9): 905-912. DOI:10.1111/apt.12682 |

| [42] |

Vleugels JLA, Hazewinkel Y, Fockens P, et al. Natural history of diminutive and small colorectal polyps:a systematic literature review[J]. Gastrointest Endosc, 2017, 85(6): 1169-1176. DOI:10.1016/j.gie.2016.12.014 |

| [43] |

Jover R, Dekker E. Surveillance after colorectal polyp removal[J]. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol, 2016, 30(6): 937-948. DOI:10.1016/j.bpg.2016.10.005 |

| [44] |

Rex DK, Ahnen DJ, Baron JA, et al. Serrated lesions of the colorectum:review and recommendations from an expert panel[J]. Am J Gastroenterol, 2012, 107(9): 1315-1329. DOI:10.1038/ajg.2012.161 |

| [45] |

中华医学会消化内镜学分会消化系早癌内镜诊断与治疗协作组, 中华医学会消化病学分会消化道肿瘤协作组, 中华医学会消化内镜学分会肠道学组, 等.中国早期结直肠癌及癌前病变筛查及诊治共识意见(2014年11月·重庆)[J].中华内科杂志, 2015, 54(4): 375-389. DOI: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0578-1426.2015.04.024. Early Cancer Endoscopy Diagnosis and Treatment Collaboration Group of Chinese Medical Association of Digestive Endoscopy Branch, The Collaboration Group of Gastrointestinal Tumors, Society of Digestive Diseases, Chinese Medical Association, and the Intestinal Group, Society of Digestive Endoscopy, Chinese Medical Association, et al. Consensus on screening, diagnosis and treatment of early colorectal cancer and precancerous lesions in China[J]. Chin J Intern Med, 2015, 54(4): 375-389. DOI: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0578-1426.2015.04.024. |

| [46] |

Bonnington SN, Rutter MD. Surveillance of colonic polyps:are we getting it right?[J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2016, 22(6): 1925-1934. DOI:10.3748/wjg.v22.i6.1925 |

| [47] |

Lew JB, St John DJB, Xu XM, et al. Long-term evaluation of benefits, harms, and cost-effectiveness of the National Bowel Cancer Screening Program in Australia:a modelling study[J]. Lancet Public Health, 2017, 2(7): e331-340. DOI:10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30105-6 |

2019, Vol. 40

2019, Vol. 40