文章信息

- 赵枫, 杜文琼, 申嘉欣, 郭玲玲, 王颖, 王科科, 张萍, 冯永亮, 杨海澜, 王素萍, 邬惟为, Zhang Yawei.

- Zhao Feng, Du Wenqiong, Shen Jiaxin, Guo Lingling, Wang Ying, Wang Keke, Zhang Ping, Feng Yongliang, Yang Hailan, Wang Suping, Wu Weiwei, Zhang Yawei.

- 孕期膳食与小于胎龄儿的关系

- Association between maternal dietary intake and the incidence of babies with small for gestational age

- 中华流行病学杂志, 2019, 40(6): 697-701

- Chinese Journal of Epidemiology, 2019, 40(6): 697-701

- http://dx.doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2019.06.018

-

文章历史

收稿日期: 2018-11-14

2. 山西医科大学第一医院妇产科, 太原 030001;

3. 耶鲁大学公共卫生学院环境健康科学系, 美国康涅狄格州纽黑文市 06520

2. Obstetrics and Gynecology, First Affiliated Hospital of Shanxi Medical University, Taiyuan 030001, China;

3. Division of Environmental Health Scinces, School of Public Health, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut 06520, USA

小于胎龄儿(SGA)是指出生体重在同胎龄儿平均出生体重的P10以下的婴儿。在中低收入国家中其发生率已达27%[1]。SGA会明显增加围生期及远期疾病的发生[2-4]。已有研究显示,孕期膳食摄入蛋白质、脂肪及碳水化合物对胎儿生长发育有影响[5-7],但孕期蛋白质摄入是否与SGA发生风险有关仍存在争议[8-9]。同时有研究提示孕前BMI对SGA发生风险有重要作用[10-12]。孕期BMI作为衡量孕妇孕前营养状况的指标,应对不同孕前BMI人群分别提出孕期膳食建议更为合理。已有研究关注不同孕期膳食因素对胎儿出生体重的影响[13-15]。本研究将从孕早、中、晚三期来探讨孕期膳食摄入对SGA发生风险的影响,并针对不同孕前BMI人群分别给予膳食建议,以期降低SGA的发生风险。

对象与方法1.研究对象:以2012年3月至2016年9月在山西医科大学第一医院产科住院分娩的孕妇作为研究对象,共10 319例。纳入标准:愿意签署知情同意书,所需问卷信息完整,单胎活产。排除标准:死胎、死产、出生缺陷、<22孕周及大于胎龄儿。纳入研究对象8 102例母婴对,SGA 961例,对照7 141例。

2.研究方法:采取面对面调查的方式,调查问卷采用标准化的结构式调查问卷,在孕妇分娩后24 h内收集问卷信息,包括孕妇一般人口学特征、生育史、产检信息、既往患病史、生活方式、孕期膳食摄入情况等。其中,膳食摄入信息的收集采用经过验证的半定量食物频数表,该表包括怀孕前3个月、第4~6月和后3个月的饮食情况,如摄入的食物种类、平均每次食用量及进食次数等。按照中国食物成分表将摄入食物转化为每日膳食营养素摄入量[16]。

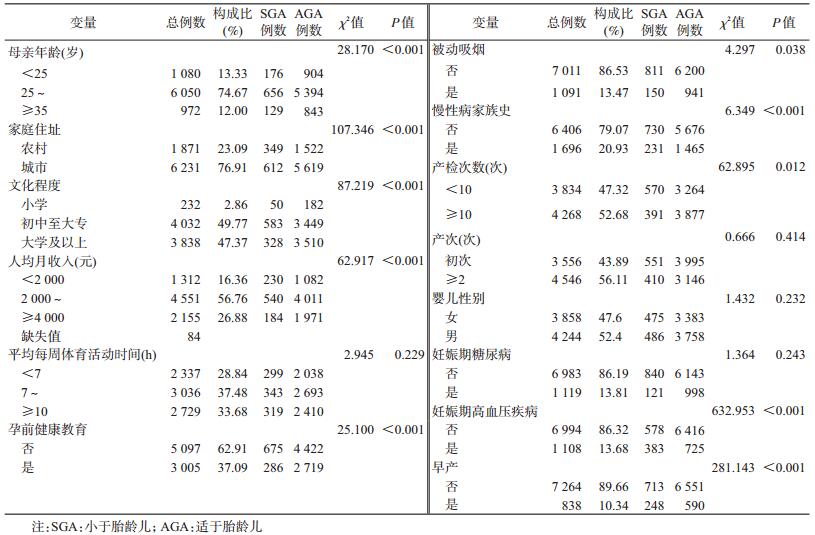

3.标准及分组:将出生体重在同胎龄儿平均出生体重的P10以下的母婴对纳入SGA组;将出生体重在同胎龄儿平均出生体重P10~P90之间的婴儿纳入适于胎龄儿(AGA组,即对照组)。根据中国成人体质指数分类的推荐意见[17],BMI<18.5 kg/m2为体重过低组;18.5≤BMI<24.0 kg/m2为体重正常组;BMI≥24.0 kg/m2为超重/肥胖组。按照AGA组膳食营养素摄入量的三分位数划分:摄入量<P33.3为低摄入量组;P33.3≤摄入量<P66.6为中等摄入量组;摄入量≥P66.6为高摄入量组,见表 1。

4.统计学分析:采用EpiData 3.1软件建立数据库、SAS 9.4软件进行数据清理及分析;一般情况描述计量资料用x ± s表示,计数资料用例数和构成比表示;多因素分析采用非条件logistic回归分析,以P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。

结果1.一般情况:研究对象的年龄为14~59(28.95±4.50)岁。新生儿出生体重(3 102.02±505.19)g,孕前BMI(21.05±3.19)kg/m2,孕周为(38.49±1.95)周。

2.单因素分析:母亲年龄、家庭住址、文化程度、人均月收入、孕前健康教育、被动吸烟、慢性病家族史、产检次数、妊娠期高血压疾病、早产在SGA、AGA组中的分布差异有统计学意义(P<0.05)。见表 2。

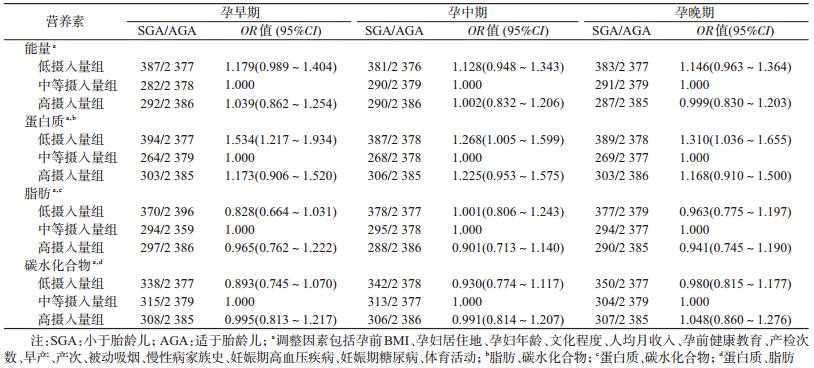

3.不同孕期膳食摄入情况对SGA发生风险的影响:孕早期(OR=1.534,95%CI:1.217~1.934)、孕中期(OR=1.268,95%CI:1.005~1.599)及孕晚期(OR=1.310,95%CI:1.036~1.655)蛋白质摄入量过低会增加SGA的发生风险,见表 3。

4.孕前BMI对SGA的影响:调整了各期能量摄入情况、体育活动及其他影响因素后,非条件logistic回归分析显示,在孕早、中、晚期中孕前低体重均是SGA的危险因素,孕前超重/肥胖均是SGA的保护因素,见表 4。

5.在不同孕前BMI人群中各孕期膳食摄入与SGA的关系:按孕前BMI水平分层后,孕前体重过低组(BMI<18.5 kg/m2)的孕妇在孕早期总能量及蛋白质的摄入量低会增加SGA的发生风险(OR=1.754,95%CI:1.125~2.734;OR=1.872,95%CI:1.033~3.395);在孕前体重正常组中(18.5≤BMI<24.0 kg/m2),孕早期膳食蛋白质摄入量低是SGA的危险因素(OR=1.465,95%CI:1.089~1.972);在超重/肥胖组中(BMI≥24.0 kg/m2)尚未发现膳食摄入与SGA的发生风险有关联。见表 5。

当前对于SGA的致病机制已经进行了大量研究,SGA发生率是影响新生儿患病率和死亡率的主要因素之一[2]。现已有研究发现孕期蛋白质、脂肪及碳水化合物摄入对SGA的发生风险有影响[8-9]。本研究分孕早、中、晚3期探讨不同孕前BMI人群中孕期膳食摄入对SGA的影响。结果显示,三大营养素中蛋白质对SGA的发生风险有影响。

当前对孕期摄入蛋白质与SGA关系的研究结果不一,有研究表明[9, 18],孕期均衡的蛋白质能量补充会使SGA的发生风险降低;而另一研究认为孕早、孕中期蛋白质的摄入情况均与胎儿生长发育无关[13]。本研究结果显示,未分层时孕早、中、晚期蛋白质摄入量较低是SGA的危险因素。按孕前BMI分层后,在孕前BMI<18.5 kg/m2人群中发现,孕早期蛋白质及能量摄入量过低是SGA的危险因素;在18.5 kg/m2≤孕前BMI<24.0 kg/m2的人群中也发现,孕早期蛋白质摄入量过低是SGA的危险因素;而在孕前BMI≥24.0 kg/m2的孕妇中,整个孕期尚未发现蛋白质与SGA的关联。提示不同孕前BMI人群在各个孕期对蛋白质的需求量不同,应该根据孕前BMI及孕期给出不同的膳食蛋白质摄入建议。孕前BMI<24.0 kg/m2的人群在孕早期蛋白质摄入量应不低于51.60 g/d;同时孕前BMI<18.5 kg/m2的孕妇在孕早期膳食能量的摄入不应低于1 146.22 kcal/d。孕前BMI≥24.0 kg/m2的人群,在整个孕期尚未发现蛋白质与SGA的关联,可能较高的孕前BMI反映了孕妇较好的营养状况,自身足够供给胎儿生长发育,因此在此人群中尚未观察到膳食摄入的蛋白质对SGA的发生风险有影响。

本研究并未发现孕期脂肪及碳水化合物摄入与SGA的关联。国外有研究提出[19],孕期摄入经加工的高脂肪肉类产品较多与低出生体重有关,也增加了SGA发生风险,但其并未深入到营养素水平探讨。Sharma等[13]认为膳食脂肪摄入量高反映了孕妇高热量、高脂肪的饮食习惯及较差的饮食质量,随着脂肪摄入量增高,出生体重降低,但该研究未考虑到孕前BMI的影响。而有关不同孕期碳水化合物摄入量与SGA关系的研究目前尚无报道。

分层后孕期膳食摄入量对SGA的作用仅出现在孕早期,孕中、晚期尚未观察到膳食摄入与SGA的关联。孕早期是胎儿宫内生长发育的关键时期,是婴儿器官的发育阶段,孕早期胎盘的形成及宫内环境对之后胎儿的生长发育有重要影响[20],因此孕早期可能是膳食因素对SGA作用的关键期。孕妇应在孕早期注意合理膳食,保证蛋白质及能量的摄入量,以预防SGA的发生。

利益冲突 所有作者均声明不存在利益冲突

| [1] |

Black RE. Global prevalence of small for gestational age births[J]. Nestlé Nutr Inst Workshop Ser, 2015, 81: 1-7. |

| [2] |

García-Basteiro AL, Quintó L, Macete E, et al. Infant mortality and morbidity associated with preterm and small-for-gestational-age births in Southern Mozambique:a retrospective cohort study[J]. PLoS One, 2017, 12(2): e0172533. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0172533 |

| [3] |

Sharma D, Shastri S, Sharma P. Intrauterine growth restriction:antenatal and postnatal aspects[J]. Clin Med Insights Pediatr, 2016, 10(10): 67-83. DOI:10.4137/CMPed.S40070 |

| [4] |

Sebastian T, Yadav B, Jeyaseelan L, et al. Small for gestational age births among South Indian women:temporal trend and risk factors from 1996 to 2010[J]. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth, 2015, 15: 7. DOI:10.1186/s12884-015-0440-4 |

| [5] |

Bobiński R, Mikulska M, Mojska H, et al. The dietary composition of women who delivered healthy full-term infants, preterm infants, and full-term infants who were small for gestational age[J]. Biol Res Nurs, 2015, 17(5): 495-502. DOI:10.1177/1099800414556529 |

| [6] |

林君儒, 张淑莲, 朱丽, 等. 中国足月小样儿发生率及影响因素分析[J]. 中华医学杂志, 2016, 96(1): 48-52. Sam Bill JR, Zhang SL, Zhu L, et al. Incidence and influencing factors of term small for gestational age infants in China[J]. Chin Med J, 2016, 96(1): 48-52. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0376-2491.2016.01.011 |

| [7] |

Zulyniak MA, Souza RJD, Shaikh M, et al. Does the impact of a plant-based diet during pregnancy on birth weight differ by ethnicity? A dietary pattern analysis from a prospective Canadian birth cohort alliance[J]. BMJ Open, 2017, 7(11): e017753. DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017753 |

| [8] |

Mukhopadhyay A, Thomas T, Bosch R, et al. Fetal sex modifies the effect of maternal macronutrient intake on the incidence of small-for-gestational-age births:a prospective observational cohort study[J]. Am J Clin Nutr, 2018, 108(4): 814-820. DOI:10.1093/ajcn/nqy161 |

| [9] |

Imdad A, Bhutta ZA. Effect of balanced protein energy supplementation during pregnancy on birth outcomes[J]. BMC Public Health, 2011, 11 Suppl 3: S17. DOI:10.1186/1471-2458-11-S3-S17 |

| [10] |

Zhang B, Yang SP, Rong Y, et al. Maternal prepregnancy body mass index and small for gestational age births in Chinese women[J]. Paediat Perinat Epidemiol, 2016, 30(6): 550-554. DOI:10.1111/ppe.12315 |

| [11] |

Shin D, Song WO. Prepregnancy body mass index is an independent risk factor for gestational hypertension, gestational diabetes, preterm labor, and small- and large-for-gestational-age infants[J]. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med, 2014, 28(14): 1679-1686. DOI:10.3109/14767058.2014.964675 |

| [12] |

Tsukamoto H, Fukuoka H, Koyasu M, et al. Risk factors for small for gestational age[J]. Pediatr Int, 2007, 49(6): 985-990. DOI:10.1111/j.1442-200X.2007.02494.x |

| [13] |

Sharma SS, Greenwood DC, Simpson N, et al. Is dietary macronutrient composition during pregnancy associated with offspring birth weight? An observational study[J]. Br J Nutr, 2018, 119(3): 330-339. DOI:10.1017/S0007114517003609 |

| [14] |

Chong MFF, Chia AR, Colega M, et al. Maternal protein intake during pregnancy is not associated with offspring birth weight in a multiethnic Asian population[J]. J Nutr, 2015, 145(6): 1303-1310. DOI:10.3945/jn.114.205948 |

| [15] |

Mani I, Dwarkanath P, Thomas T, et al. Maternal fat and fatty acid intake and birth outcomes in a South Indian population[J]. Int J Epidemiol, 2016, 45(2): 523-531. DOI:10.1093/ije/dyw010 |

| [16] |

杨月欣. 中国食物成分表 2002[M]. 北京: 北京大学医学出版社, 2002. Yang YX. China Food Composition 2002[M]. Beijing: Peking University Medical Press, 2002. |

| [17] |

中国肥胖问题工作组数据汇总分析协作组. 我国成人体重指数和腰围对相关疾病危险因素异常的预测价值:适宜体重指数和腰围切点的研究[J]. 中华流行病学杂志, 2002, 23(1): 5-10. Coorperative Meta-analysis Group of China Obesity Task Force. Predictive values of body mass index and waist circumference to risk factors of related diseases in Chinese adult population[J]. Chin J Epidemiol, 2002, 23(1): 5-10. DOI:10.3760/j.issn:0254-6450.2002.01.003 |

| [18] |

Makrides M, Anderson A, Gibson RA. Early influences of nutrition on fetal growth[J]. Nestlé Nutr Inst Workshop Ser, 2013, 71: 1-9. DOI:10.1159/000342500 |

| [19] |

Kjøllesdal MKR, Holmboe-Ottesen G. Dietary patterns and birth weight-a review[J]. Aims Public Health, 2014, 1(4): 211-225. DOI:10.3934/Publichealth.2014.4.211 |

| [20] |

Kroener L, Wang ET, Pisarska MD. Predisposing factors to abnormal first trimester placentation and the impact on fetal outcomes[J]. Semin Reprod Med, 2015, 34(1): 27-35. DOI:10.1055/s-0035-1570029 |

2019, Vol. 40

2019, Vol. 40