文章信息

- 于悦, 郭新慧, 严寒秋, 高志勇, 李伟红, 刘白薇, 王全意.

- Yu Yue, Guo Xinhui, Yan Hanqiu, Gao Zhiyong, Li Weihong, Liu Baiwei, Wang Quanyi.

- 札如病毒急性胃肠炎暴发特征系统综述

- Systematic review on the characteristics of acute gastroenteritis outbreaks caused by sapovirus

- 中华流行病学杂志, 2019, 40(1): 93-98

- Chinese Journal of Epidemiology, 2019, 40(1): 93-98

- http://dx.doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2019.01.019

-

文章历史

收稿日期: 2018-07-19

2. 北京市房山区疾病预防控制中心 102446

2. Fangshan District Center for Diseases Control and Prevention, Beijing 102446, China Yu Yue and Guo Xinhui contributed equally to the article

札如病毒(sapovirus,SaV)和诺如病毒同属于人杯状病毒,是引起人急性胃肠炎的重要病原体之一。SaV为单股正链RNA病毒,基因组全长7.3~7.5 kb,根据衣壳区蛋白全基因序列可将SaV分为5个基因组(GⅠ~GⅤ),其中GⅠ、GⅡ、GⅣ和GⅤ感染人类[1]。世界范围内SaV急性胃肠炎暴发时有报道,为了解SaV急性胃肠炎暴发特征,为防控工作提供依据,本研究对发表的SaV急性胃肠炎暴发文献进行了系统综述。

资料与方法1.文献检索:以“札如病毒”或“扎如病毒”或“札幌样病毒”或“札幌病毒”或“扎幌病毒”或“扎幌样病毒”为关键词在中国知网、万方数据库检索,或以“Sapovirus”或“Sapporo-like virus”在PubMed、Web of Science数据库检索,再从搜索到的文献确定SaV急性胃肠炎暴发文献。

2.文献纳入标准:①发表于2018年1月以前;②能提供SaV急性胃肠炎暴发发生时间、发生地点等流行病学信息;③PCR检测患者粪便或呕吐物SaV核酸阳性。

3.文献排除标准:符合其中之一即被排除:①可疑SaV感染;②与其他病原混合感染;③未找到全文且摘要未提及有效信息的文献;④语言不是中文或英文,且无英文摘要的文献;⑤综述类文献。

4.数据提取和统计学分析:用WPS 2016软件建立数据库,进行数据录入、整理。重复报道的案例仅统计1次,将重复报道文献包含的信息进行归纳整合。文献信息收集内容包括疫情发生时间、地点、场所、发病人数、人群分布、传播途径、病毒基因型、患者临床症状等。从文献检索、评价、数据提取均采用双人独立分析,结果不一致时再由第3人进行仲裁。采用SPSS 20.0统计学软件分析,不同组间率的比较采用χ2检验。以P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。

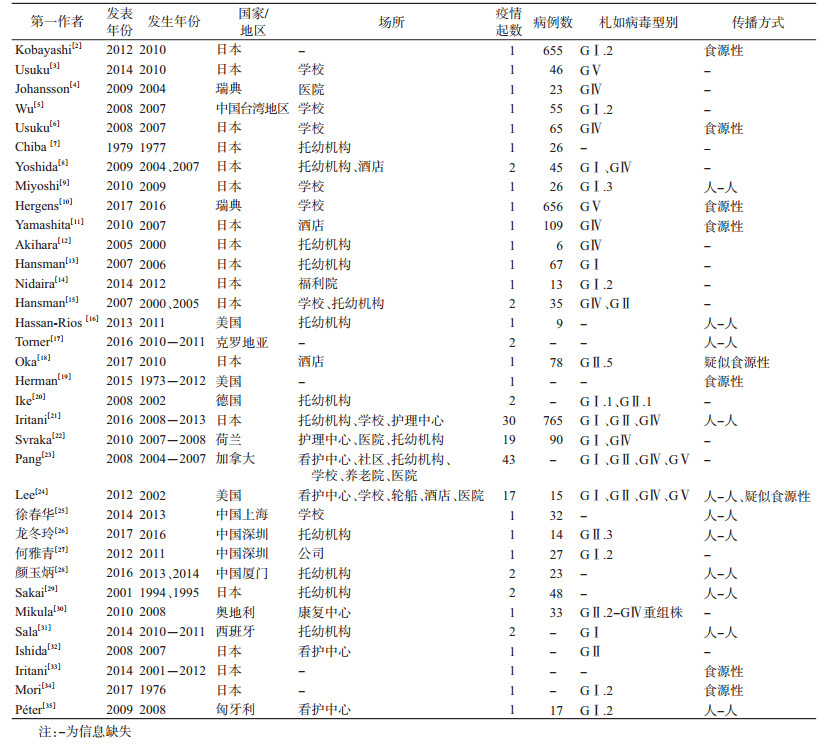

结果1.文献整理情况:根据检索策略,通过Note Express去重,初步检索得到1 578篇文献。通过阅读题目和摘要,筛选出52篇SaV急性胃肠炎暴发相关文献。排除18篇,其中12篇涉及混合感染,2篇涉及重复报告,3篇非中/英文文献且无法获得具体信息,1篇信息不全。最终纳入34篇文献。见表 1。

2.流行病学特征:34篇文献报告SaV急性胃肠炎暴发146起,发生时间范围为1976年10月至2016年4月。46起暴发提供了具体病例数,单起暴发涉及病例5~656人,中位数为23人,共涉及病例3 298人。40起暴发提供疫情持续时间,中位数为8 d(1~31 d)。18起暴发有罹患率信息,最高76.47%,最低5.54%,中位数为20.71%。仅2起报告了SaV潜伏期,但结果较为相近,最短分别为14.5 h和18.0 h,最长分别为64.0 h和66.5 h,中位数分别为32 h和38 h。26起暴发可获得患者年龄信息,发病人群以<18岁未成年人为主,占67.16%(906/1 349)。

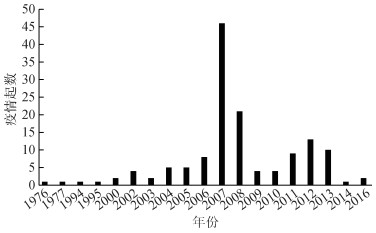

(1)时间分布:共140起暴发获得疫情发生年份资料,最早报告于1976年,年份分布见图 1。其中,2007-2008年以及2011-2013年属高发年份。

|

| 图 1 1976-2016年札如病毒急性胃肠炎暴发年报告疫情起数 |

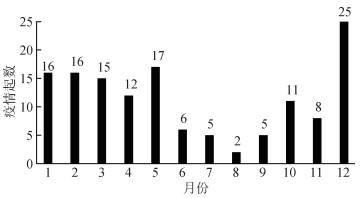

138起暴发报告了发生月份,均发生于北半球。SaV急性胃肠炎四季均有报告,疫情主要发生在冬春季。8月发生暴发最少(2起);12月发生暴发最多(25起),主要发生于温度较低月份,见图 2。

|

| 图 2 1976-2016年札如病毒急性胃肠炎暴发按月累计报告疫情起数 |

(2)地区分布:146起暴发报告来自亚洲、北美洲和欧洲地区,分布在11个国家,均位于北半球。日本报告暴发最多(49起),其次为加拿大(43起)、美国(19起)、荷兰(19起)、中国(6起)、德国(2起)、瑞典(2起)、西班牙(2起)、克罗地亚(2起)、奥地利(1起)和匈牙利(1起)。我国报告的6起SaV急性胃肠炎暴发均来自东南沿海地区,其中厦门市2起、深圳市2起、上海市1起、台湾地区1起。

(3)场所分布:共141起暴发可以获得发生场所资料,报告最多的为托幼机构(48/141,34.04%),其次是长期看护机构(41/141,29.08%)、医院(16/141,11.35 %)、学校(13/141,9.22%)、养老院(8/141,5.67%)和社区(6/141,4.26%),酒店或餐馆(4/141,2.84%),福利院、轮船、公司和康复中心各1起。

(4)传播途径:146起疫情中,39起报告了传播途径,其中29起为人与人传播(74.36%),7起(17.95%)为食源性传播,3起(7.69%)疑似食源性传播。

(5)病原学特征:146起暴发中,确定病毒组别的有119起。其中,51起疫情(42.86%)由GⅠ组SaV引起,45起(37.82%)由GⅣ组SaV引起,18起(15.13%)由GⅡ组SaV引起,4起(3.36%)由GⅤ组SaV引起,1起(0.84%)由GⅡ-GⅣ组重组SaV引起。57起暴发报告了基因型别,GⅠ.2占比最多(28/57,49.12%),其次为GⅠ.1(8)、GⅣ.1(7)、GⅡ.3(6)、GⅠ.3(3)、GⅡ.1(3)、GⅡ.2(1)和GⅡ.5(1)。SaV暴发在2007-2008年和2011-2013年出现报告高峰,2007年SaV的优势流行株为GⅣ组,2008、2011-2013年的流行优势株则为GⅠ组。

(6)临床症状:31起暴发共1 704例病例具有临床症状信息,腹泻最常见(1 331/1 704,78.12%),然后分别为恶心(829/1 198,69.20%)、腹痛(840/1 328,63.25%)、呕吐(824/1 704,48.36%)以及发热(529/1 531,34.53%)。

25起基因型明确的暴发中,GⅠ组和GⅣ组SaV感染所致胃肠炎临床表现以腹泻(722/808,89.34%;310/416,74.54%)为主,GⅤ组SaV感染呕吐较多(206/309,66.67%)。3种基因组SaV感染患者之间腹泻和呕吐发生率两两比较差异均有统计学意义(P<0.001)。

讨论日本学者于1979年报告了发生于札幌市的1起SaV急性胃肠炎暴发[7],本研究中1976年的SaV疫情为日本学者2017年对历史保存样本回顾性调查发现[34]。1976-2006年文献报告的SaV暴发数量较少,2007-2008年以及2011-2013年报告较多。本研究结果显示,SaV暴发偏好温度较低月份,冬季高发。Dey等[36]对2003-2009年日本5个地区(札幌、东京、舞鹤、大阪、佐贺)共3 232例散发婴幼儿胃肠炎患者进行了SaV检测,10月至次年3月检出率最高,与本研究结果相似。冬季人们室外活动减少,集体单位室内人员密度较大,SaV在封闭的空间内便于传播,因而易发生感染暴发。日本、加拿大、美国和荷兰等国报告疫情较多,这些国家大多属于温带气候。分析原因:这些国家传染病的防控工作开展较好,检验技术水平更先进,能够及时发现并报告疫情;另一方面,这些地区冬季相对较长,温度较低,有利于SaV的生存传播;此外,这些国家都为沿海国家,沿海地区贝类的生产和消费较为常见,贝类可被SaV污染[37],人类接触或食用贝类可能导致暴发[33]。从场所来看,暴发主要发生在托幼机构、长期看护机构、医院和学校等。分析可能的原因其一是由于儿童、老年人等人群免疫力较为低下,且没有养成良好的卫生习惯或卫生意识较差,是SaV的易感人群;其二是这些场所大多人口密集,且共同用餐、使用公共餐具、使用公共空间,易造成传染病的传播。

本研究发现,GⅠ组和GⅣ组病毒是SaV暴发中的优势流行株,而在散发病例中优势流行株主要为GⅠ组和GⅡ组[38]。可能不同型别SaV感染特点有所差异,但仍需更多研究证实。2007年SaV的优势流行株为GⅣ组,2008、2011-2013年的流行优势株则为GⅠ组。SaV感染后可产生短期的基因型特异性免疫,但对其他基因型无免疫保护[39]。2007年GⅣ组毒株出现引起疫情报告增加,感染过GⅣ组毒株的人群获得对该基因型的免疫保护,但对其他基因型无保护性免疫。随后2008年GⅠ组毒株活动增加,由于感染后免疫保护期较短,2011-2013年GⅠ组毒株又引起疫情报告增加。本研究结果显示不同基因型SaV感染者的临床症状不完全相同,GⅠ组和GⅣ组SaV感染者腹泻症状多见,GⅤ组SaV感染者较多有呕吐症状。这些差异可能是不同型别病原特性不同,也可能是患者年龄因素干扰所致,尚需进一步研究。目前SaV监测和研究对象主要是腹泻患者,但并非所有患者均有腹泻症状,因此在选择监测或研究对象时要予以注意。本研究仅有57起暴发报告了具体基因型,而且多数仅有衣壳区基因分型,大多数暴发没有确定基因型,不利于流行病学研究和疾病防控。建议以后的研究尽可能进行病原型别鉴定,最好同时确定聚合酶区和衣壳区分型,以及时发现重组株。

世界范围内SaV暴发的报告不多,远少于诺如病毒。分析原因:SaV可能不易感染人类且传播力不如诺如病毒;感染后症状轻于诺如病毒[1],暴发可能不易被识别;检测手段尚不普及,许多国家和地区没有开展SaV检测,无法发现暴发。目前SaV的致病机制、感染量、在外环境中的存活能力、机体免疫保护机制、宿主易感性等尚不明确[1]。因而前述的一些推测尚无证据支持。

本研究存在不足。多数疫情没有报告暴发持续时间、达到峰值时间、罹患率等,因而无法对相关流行病学特征进行详细分析;经济发达国家及地区SaV暴发更容易被报告和发表,导致地区分布分析可能存在偏倚;绝大多数长期看护机构发生的暴发没有报告患者的具体年龄,患者年龄分析时低估了老年人患者比例;多数暴发没有报告传播途径,水源性传播没有报告,可能对暴发传播途径占比有一定影响;受实验室检测技术限制,多数毒株没有详细的基因分型,无法详细分析其分子流行病学特征。

近年来我国诺如病毒急性胃肠炎暴发监测工作已取得较大进展,其流行特征已有基本了解,也出台了相应防控方案。但我国SaV暴发报告较少,开展检测工作的地区不多,其流行特征尚不明确,亦需要开展相应的培训工作和制定相应的防控方案,在有条件的地区开展监测工作。实际工作中如果疑似诺如病毒的疫情未有检测到病原,需排除SaV感染。

综上所述,SaV暴发主要为发达国家报告,寒冷月份高发,常发生于托幼机构和长期看护机构,主要流行株为GⅠ组和GⅣ组。我国SaV暴发防控工作较为落后,需开展相应的培训工作,在有条件的地区开展SaV暴发监测工作。

利益冲突 所有作者均声明不存在利益冲突

| [1] |

Oka T, Wang QH, Katayama K, et al. Comprehensive review of human sapoviruses[J]. Clin Microbiol Rev, 2015, 28(1): 32-53. DOI:10.1128/CMR.00011-14 |

| [2] |

Kobayashi S, Fujiwara N, Yasui Y, et al. A foodborne outbreak of sapovirus linked to catered box lunches in Japan[J]. Arch Virol, 2012, 157(10): 1995-1997. DOI:10.1007/s00705-012-1394-8 |

| [3] |

Usuku S, Kumazaki M. A gastroenteritis outbreak attributed to sapovirusgenogroup V in Yokohama, Japan[J]. Jpn J Infect Dis, 2014, 67(5): 411-412. DOI:10.7883/yoken.67.411 |

| [4] |

Johansson PJH, Bergentoft K, Larsson PA, et al. A nosocomial sapovirus-associated outbreak of gastroenteritis in adults[J]. Scand J Infect Dis, 2005, 37(3): 200-204. DOI:10.1080/00365540410020974 |

| [5] |

Wu FT, Oka T, Takeda N, et al. Acute gastroenteritis caused by Gi/2 sapovirus, Taiwan, 2007[J]. Emerg Infect Dis, 2008, 14(7): 1169-1171. DOI:10.3201/eid1407.071531 |

| [6] |

Usuku S, Kumazaki M, Kitamura K, et al. An outbreak of food-borne gastroenteritis due to sapovirus among junior high school students[J]. Jpn J Infect Dis, 2008, 61(6): 438-441. DOI:10.1097/QAI.0b013e31817c1ed0 |

| [7] |

Chiba S, Sakuma Y, Kogasaka R, et al. An outbreak of gastroenteritis associated with calicivirus in an infant home[J]. J Med Virol, 1979, 4(4): 249-254. DOI:10.1002/jmv.1890040402 |

| [8] |

Yoshida T, Kasuo S, Azegami Y, et al. Characterization of sapoviruses detected in gastroenteritis outbreaks and identification of asymptomatic adults with high viral load[J]. J Clin Virol, 2009, 45(1): 67-71. DOI:10.1016/j.jcv.2009.03.003 |

| [9] |

Miyoshi M, Yoshizumi S, Kanda N, et al. Different genotypic sapoviruses detected in two simultaneous outbreaks of gastroenteritis among schoolchildren in the same school district in Hokkaido, Japan[J]. Jpn J Infect Dis, 2010, 63(1): 75-78. DOI:10.1258/ijsa.2009.008500 |

| [10] |

Hergens MP, Öhd JN, Alm E, et al. Investigation of a food-borne outbreak of gastroenteritis in a school canteen revealed a variant of sapovirusgenogroup V not detected by standard PCR, Sollentuna, Sweden, 2016[J]. Eurosurveillance, 2017, 22(22): 30543. DOI:10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2017.22.22.30543 |

| [11] |

Yamashita Y, Ootsuka Y, Kondo R, et al. Molecular characterization of Sapovirus detected in a gastroenteritis outbreak at a wedding hall[J]. J Med Virol, 2010, 82(4): 720-726. DOI:10.1002/jmv.21646 |

| [12] |

Akihara S, Phan TG, Nguyen TA, et al. Existence of multiple outbreaks of viral gastroenteritis among infants in a day care center in Japan[J]. Arch Virol, 2005, 150(10): 2061-2075. DOI:10.1007/s00705-005-0540-y |

| [13] |

Hansman GS, Saito H, Shibata C, et al. Outbreak of gastroenteritis due to sapovirus[J]. J Clin Microbiol, 2007, 45(4): 1347-1349. DOI:10.1128/JCM.01854-06 |

| [14] |

Nidaira M, Taira K, Kato T, et al. Phylogenetic analysis of sapovirus detected from an outbreak of acute gastroenteritis on Ishigaki Island (Okinawa Prefecture, Japan) in 2012[J]. Jpn J Infect Dis, 2014, 67(2): 141-143. DOI:10.7883/yoken.67.141 |

| [15] |

Hansman GS, Ishida S, Yoshizumi S, et al. Recombinant sapovirus gastroenteritis, Japan[J]. Emerg Infect Dis, 2007, 13(5): 786-788. DOI:10.3201/eid1305.070049 |

| [16] |

Hassan-Rios E, Torres P, Munoz E, et al. Sapovirus gastroenteritis in preschool center, Puerto Rico, 2011[J]. Emerg Infect Dis, 2013, 19(1): 174-175. DOI:10.3201/eid1901.120690 |

| [17] |

Torner N, Martinez A, Broner S, et al. Epidemiology of acute gastroenteritis outbreaks caused by human calicivirus (norovirus and sapovirus) in Catalonia:a two year prospective study, 2010-2011[J]. PLoS One, 2016, 11(4): e0152503. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0152503 |

| [18] |

Oka T, Doan YH, Haga K, et al. Genetic characterization of rare genotype GⅡ.5 sapovirus strain detected from a suspected food-borne gastroenteritis outbreak among adults in Japan in 2010[J]. Jpn J Infect Dis, 2017, 70(2): 223-224. DOI:10.7883/yoken.JJID.2016.468 |

| [19] |

Herman KM, Hall AJ, Gould LH. Outbreaks attributed to fresh leafy vegetables, United States, 1973-2012[J]. Epidemiol Infect, 2015, 143(14): 3011-3021. DOI:10.1017/S0950268815000047 |

| [20] |

Ike AC, Hartelt K, Oehme RM, et al. Detection and characterization of sapoviruses in outbreaks of gastroenteritis in southwest Germany[J]. J Clin Virol, 2008, 43(1): 37-41. DOI:10.1016/j.jcv.2008.04.003 |

| [21] |

Iritani N, Yamamoto SP, Abe N, et al. Epidemics of GⅠ.2 sapovirus in gastroenteritis outbreaks during 2012-2013 in Osaka city, Japan[J]. J Med Virol, 2016, 88(7): 1187-1193. DOI:10.1002/jmv.24451 |

| [22] |

Svraka S, Vennema H, van der Veer B, et al. Epidemiology and genotype analysis of emerging sapovirus-associated infections across Europe[J]. J Clin Microbiol, 2010, 48(6): 2191-2198. DOI:10.1128/JCM.02427-09 |

| [23] |

Pang XL, Lee BE, Tyrrell GJ, et al. Epidemiology and genotype analysis of sapovirus associated with gastroenteritis outbreaks in Alberta, Canada:2004-2007[J]. J Infect Dis, 2009, 199(4): 547-551. DOI:10.1086/596210 |

| [24] |

Lee LE, Cebelinski EA, Fuller C, et al. Sapovirus outbreaks in long-term care facilities, Oregon and Minnesota, USA, 2002-2009[J]. Emerg Infect Dis, 2012, 18(5): 873-876. DOI:10.3201/eid1805.111843 |

| [25] |

徐春华, 王志, 王健. 一起小学札如病毒急性胃肠炎聚集性疫情调查[J]. 中国消毒学杂志, 2014, 31(5): 490-492. Xu CH, Wang Z, Wang J. Investigation on the cause of clustering outbreak of acute sapovirus gastroenteritis epidemic in primary students[J]. Chin J Disinfect, 2014, 31(5): 490-492. |

| [26] |

龙冬玲, 庄辉元, 靳淼, 等. 一起由札如病毒引起的急性胃肠炎暴发疫情的分子流行病学研究[J]. 国际病毒学杂志, 2017, 24(3): 183-186. Long DL, Zhuang HY, Jin M, et al. Molecular epidemiology of an acute gastroenteritis outbreak caused by sapovirus[J]. Int J Virol, 2017, 24(3): 183-186. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1673-4092.2017.03.009 |

| [27] |

何雅青, 卓菲, 张海龙, 等. 一起札如病毒所致成年人急性胃肠炎暴发的分子流行病学研究[J]. 疾病监测, 2012, 27(2): 101-103. He YQ, Zhuo F, Zhang HL, et al. Molecular epidemiology of a cute gastroenteritis outbreak caused by Sapovirus in Adults[J]. Dis Surveill, 2012, 27(2): 101-103. DOI:10.3784/j.issn.1003-9961.2012.2.006 |

| [28] |

颜玉炳, 苏成豪. 札如病毒致幼托儿童急性胃肠炎爆发疫情特征分析[J]. 中国校医, 2016, 30(5): 364-366. Yan YB, Su CH. Analysis of epidemiological characteristics of acute gastroenteritis outbreaks caused by sapovirus in preschool children[J]. Chin J School Doctor, 2016, 30(5): 364-366. |

| [29] |

Sakai Y, Nakata S, Tatsumi M, et al. Clinical severity of norwalk virus and sapporo virus gastroenteritis in children in Hokkaido, Japan[J]. Pediatr Infect Dis J, 2001, 20(9): 849-853. DOI:10.1097/00006454-200109000-00005 |

| [30] |

Mikula C, Springer B, Reichart S, et al. Sapovirus in adults in rehabilitation center, upper Austria[J]. Emerg Infect Dis, 2010, 16(7): 1186-1187. DOI:10.3201/eid1607.091789 |

| [31] |

Sala MR, Broner S, Moreno A, et al. Cases of acute gastroenteritis due to calicivirus in outbreaks:clinical differences by age and aetiologicalagent[J]. Clin Microbiol Infect, 2014, 20(8): 793-798. DOI:10.1111/1469-0691.12522 |

| [32] |

Ishida S, Yoshizumi S, Miyoshi M, et al. Characterization of sapoviruses detected in Hokkaido, Japan[J]. Jpn J Infect Dis, 2008, 61(6): 504-506. |

| [33] |

Iritani N, Kaida A, Abe N, et al. Detection and genetic characterization of human enteric viruses in oyster-associated gastroenteritis outbreaks between 2001 and 2012 in Osaka city, Japan[J]. J Med Virol, 2014, 86(12): 2019-2025. DOI:10.1002/jmv.23883 |

| [34] |

Mori K, Nagano M, Kimoto K, et al. Detection of enteric viruses in fecal specimens from nonbacterial foodborne gastroenteritis outbreaks in Tokyo, Japan between 1966 and 1983[J]. Jpn J Infect Dis, 2017, 70(2): 143-151. DOI:10.7883/yoken.JJID.2015.456 |

| [35] |

Péter P, Zoltán K, Andrea K, et al. First gastroenteritis outbreak caused by sapovirus (GⅠ2) in Hungary-part of an international epidemic?[J]. Orv Hetil, 2009, 150(26): 1223-1229. DOI:10.1556/OH.2009.28628 |

| [36] |

Dey SK, Phathammavong O, Nguyen TD, et al. Seasonal pattern and genotype distribution of sapovirus infection in Japan, 2003-2009[J]. Epidemiol Infect, 2012, 140(1): 74-77. DOI:10.1017/S0950268811000240 |

| [37] |

Varela MF, Hooper AS, Rivadulla E, et al. Human sapovirus in mussels from Ría do Burgo, A Coruña (Spain)[J]. Food Environ Virol, 2016, 8(3): 187-193. DOI:10.1007/s12560-016-9242-8 |

| [38] |

周锦辉, 严寒秋, 高志勇. 人类札如病毒流行概况[J]. 国际病毒学杂志, 2017, 24(2): 133-136. Zhou JH, Yan HQ, Gao ZY. Advarces in epidemiology of human sapovirus[J]. Int J Virol, 2017, 24(2): 133-136. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1673-4092.2017.02.016 |

| [39] |

Harada S, Oka T, Tokuoka E, et al. A confirmation of sapovirus re-infection gastroenteritis cases with different genogroups and genetic shifts in the evolving sapovirus genotypes, 2002-2011[J]. Arch Virol, 2013, 158(12): 2641-2642. DOI:10.1007/s00705-013-1757-9 |

2019, Vol. 40

2019, Vol. 40