文章信息

- 戚娟, 梁春梅, 严双琴, 李志娟, 李娟, 黄锟, 向海云, 陶翊然, 郝加虎, 童世庐, 陶芳标.

- Qi Juan, Liang Chunmei, Yan Shuangqin, Li Zhijuan, Li Juan, Huang Kun, Xiang Haiyun, Tao Yiran, Hao Jiahu, Tong Shilu, Tao Fangbiao.

- 铊暴露与出生结局的关联研究

- Study on the relationship of thallium exposure and outcomes of births

- 中华流行病学杂志, 2018, 39(8): 1112-1116

- Chinese Journal of Epidemiology, 2018, 39(8): 1112-1116

- http://dx.doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2018.08.019

-

文章历史

收稿日期: 2018-03-06

2. 243000 马鞍山市妇幼保健院;

3. 200127 上海交通大学医学院儿童医学中心临床流行病学与生物统计研究室

2. Ma'anshan Maternal and Child Health Center, Ma'anshan 243000, China;

3. Department of Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Shanghai Children's Medical Center School of Medicine, Shanghai Jiaotong University, Shanghai 200127, China

铊(thallium)是一种人体非必需微量元素,被广泛应用于化工、电子、医药、航天、高能物理、超导等行业[1]。全球每年约有5 000吨铊被释放到环境中,污染问题日益严重,对人体的危害越来越引起人们关注[2-3]。胎儿期是生长发育的关键时期,孕期铊暴露易对子代健康造成影响。孕期铊中毒,可增加胎儿死亡、先天畸形等风险[4],分娩前较高尿铊水平可增加新生儿低出生体重、早产等风险[5-6]。本研究对马鞍山市孕妇孕早期、孕中期外周血和新生儿脐血中铊浓度进行检测,分析铊暴露对出生结局的影响,为孕期保健提供合理依据。

对象与方法1.研究对象:基于马鞍山市优生优育出生队列(Ma’anshan Birth Cohort,MABC),以2013年5月至2014年9月在马鞍山市妇幼保健院纳入的3 474名孕妇作为研究对象,具体纳入标准见文献[7]。剔除双胎妊娠39名、早产(<32周)5名、胚停75名、自然流产45名、治疗性引产30名、死胎死产10名、宫外孕2名,慢性疾病19名(糖尿病合并妊娠13名、慢性高血压6名),孕早、中期外周血和脐血三期血样全缺失7例,出生结局数据缺失6例。最终纳入符合标准孕妇3 236名,收集孕早期外周血2 954份、孕中期外周血3 083份、脐血2 707份。本研究经安徽医科大学伦理委员会批准,所有研究对象均签署知情同意书。

2.研究方法:

(1)资料收集:采用自行编制的调查问卷《孕产期母婴健康记录表》,分别于孕早(<14周)、中(平均孕26周)、晚期(平均孕34周)进行问卷调查,内容包括孕妇一般人口统计学信息;既往妊娠史及疾病史;吸烟、饮酒;营养补充剂及药物使用;产前检查结果等。并于孕早、中期问卷调查时采集孕妇外周血、分娩后立即采集新生儿脐血。血液收集后立即离心,取上清于PP管中,-80 ℃冰箱保存待测。新生儿出生体重、身长、头围摘自医学出生记录。相关信息和样本采集均由经过培训的研究人员完成。

(2)血铊浓度检测:用1%稀硝酸溶液1 : 25稀释血清样品,使用NexION350X电感耦合等离子质谱仪(PerkinElmer公司)检测血清中Tl205元素含量,具体检测方法见文献[8]。为了保证检测的准确性,使用血清微量元素L-1(批号:1309438,购自挪威Seronorm公司)进行质量控制。铊的检出限为0.000 2 μg/L,本研究中铊的检出率为100.00%,日间和日内相对标准偏差分别为5.45%、3.93%,加入1 μg/L标准物后回收率为99.59%。

3.统计学分析:应用EpiData 3.0软件进行数据双录入,采用SPSS 16.0软件进行统计学分析。定量资料统计描述采用x±s,定性资料采用频数和构成比,孕妇外周血及新生儿脐血中铊浓度均呈正偏态分布,以M和QR表示;孕早、中期外周血和新生儿脐血中铊浓度采用Spearman相关和配对Mann- Whitney检验分析;孕期外周血和脐血中铊浓度经对数转换后,采用单因素方差分析和t检验分析不同孕妇铊分布特征,将单因素分析中有统计学意义以及其他文献已知相关混杂因素作为控制因素,运用多元线性回归模型分析孕期外周血和脐血中铊浓度与出生结局的关联。以出生结局(出生体重、身长、头围)为因变量,经对数转换后血清铊浓度为自变量,控制变量为孕妇年龄、孕前BMI、孕期增重、父母身高、孕妇居住地、文化程度、人均月收入、产次、孕妇吸烟、饮酒、妊娠期并发症(糖尿病、高血压)、分娩方式、出生时孕周。检验水准为α=0.05。

结果1.孕妇和新生儿基本情况:3 236名孕妇年龄为(26.61±3.64)岁。新生儿中50.9%(n=1 647)为男婴,49.1%(n=1 589)为女婴,婴儿体重为(3 368.41± 440.28)g,身长为(50.03±1.96)cm,头围为(34.05±1.55)cm。

2.孕妇外周血及新生儿脐血中铊浓度:孕妇外周血和新生儿脐血中铊元素的检出率均为100.00%,孕妇孕早、中期外周血及新生儿脐血中铊浓度分别为61.7(50.8~77.0)、60.3(50.8~75.2)和38.5(33.6~44.1)ng/L。配对Mann-Whitney检验分析结果显示,铊元素在孕早期外周血及孕中期外周血(P=0.01)、孕早期外周血与脐血(P<0.001)、孕中期外周血与脐血(P<0.001)中差异有统计学意义。Spearman相关分析结果显示,铊浓度在孕早期外周血与孕中期外周血(r=0.111,P<0.001)、孕早期外周血与脐血(r=0.071,P<0.001)之间呈正相关,在孕中期外周血与脐血(r=0.014,P=0.468)之间的相关性无统计学意义。见表 1。

3.不同特征孕妇铊暴露水平:孕前BMI、居住地与孕早、中期外周血铊浓度有统计学关联,差异有统计学意义(均P<0.05);孕妇年龄与新生儿脐血中铊浓度有关,不同年龄组间差异有统计学意义(P=0.036)。铊浓度在不同文化程度、人均月收入、孕妇是否吸烟、饮酒等组间分布差异无统计学意义(P>0.05)。见表 2。

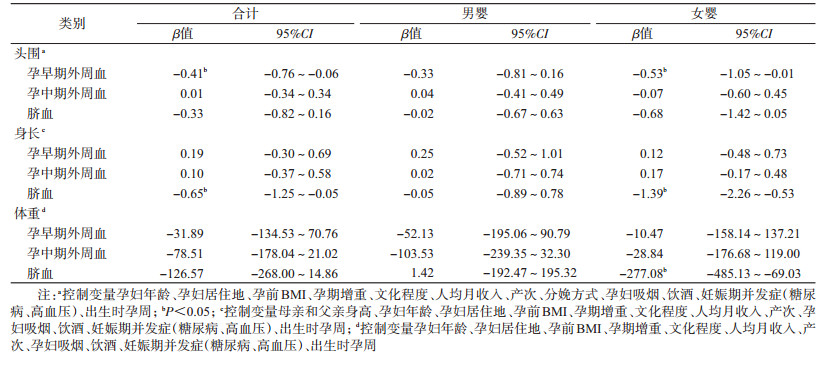

4.孕妇孕期和新生儿脐血中铊浓度与出生结局关联的多元线性回归分析:调整混杂因素后,孕早期外周血铊浓度与新生儿头围呈负相关,外周血铊浓度对数值每增加1个单位,新生儿头围减少0.41(95%CI:-0.76~-0.06)cm;脐血中铊浓度与新生儿身长呈负相关,脐血铊浓度对数值每增加1个单位,新生儿身长减少0.65(95%CI:-1.25~-0.05)cm;孕中期外周血铊浓度与新生儿出生体重、身长、头围均无显著关联(P>0.05)。性别分层分析显示,在女婴中,孕早期外周血铊浓度与新生儿头围呈负相关(β=-0.53,95%CI:-1.05~-0.01),脐血中铊浓度与新生儿体重(β=-277.08,95%CI:-485.13~-69.03)、身长(β=-1.39,95%CI:-2.26~-0.53)呈负相关。在男婴中,各期铊暴露与新生儿出生体重、身长、头围均无关联(P>0.05)。见表 3。

5.敏感性分析:为检验模型的稳定性,在多元线性回归模型的基础上增加了以下敏感性分析:保留孕早、中期外周血和脐血中铊数据全部完整的研究对象,进一步调整孕期营养剂的补充(叶酸、钙剂),结果无明显改变。

讨论铊是一种优先控制污染物,但近年来在环境中不断蓄积[9]。研究发现韩国水泥厂附近土壤中铊浓度为1.20~12.91 mg/kg[10],法国南部酸性矿井排水系统中铊浓度高达534 μg/L[11]。Liu等[12]的研究结果显示,中国广州市一家钢铁厂周围土壤中铊平均浓度为1.34 mg/kg,蔬菜中为0.89~1.80 mg/kg,大多数蔬菜中铊浓度(如莴苣)超过了德国食品环境质量标准中其最大允许水平(0.5 mg/kg)。美国国家健康与营养调查研究发现从1999-2012年美国人群尿铊浓度逐渐上升[13]。由此可见,当前铊污染形势相当严峻,且环境铊污染对居民健康的危害一直未得到有效控制。

本研究基于马鞍山市优生优育出生队列,调查了妊娠孕妇不同孕期及脐血中铊暴露情况。本研究中孕期铊暴露水平高于克罗地亚共和国东部人群水平(<0.05 μg/L)[14],脐血中铊浓度明显高于中国上海市(20.0 ng/L)和比利时弗兰德斯地区(0.017 μg/L)[15-16],但低于中国大连地区[(42.0±29.2)ng/L][17]。研究发现铊浓度在孕妇孕早、中期外周血和新生儿脐血中逐渐下降,这与其他研究结果一致[18-20],可能与妊娠期的生理变化有关,如孕期血浆量增加[21]。这可能反映了怀孕期间金属暴露的主要变化及不同妊娠期新陈代谢的改变,某一孕期外周血铊浓度可以作为产前铊暴露的生物标记物用来估计整个孕期铊暴露水平。铊浓度在孕早期外周血与脐血之间呈正相关,提示孕妇从外界环境暴露于铊浓度越高,经胎盘转运进入胎儿体内的铊含量就越多。但本研究发现孕中期外周血与脐血之间无统计学关联,需要进一步研究。

国内外关于孕期铊暴露水平与出生时体格发育的研究多集中在出生体重,有研究表明孕晚期和脐血中铊暴露可降低新生儿出生体重[20],本研究结果显示,脐血中铊浓度对新生儿出生体重的影响存在性别差异,铊浓度与女童出生体重呈负相关,这与Govarts等[16]的研究结果一致。动物研究发现铊在大脑内的残留可对大脑造成延迟影响[22],鸡胚铊暴露可导致鸡胚胫骨短小弯曲、发育迟缓、甲状腺机能低下[23]。本研究发现孕早期外周血铊浓度与新生儿头围呈负相关,脐血中铊浓度与新生儿身长呈负相关。同时,研究发现铊对胎儿的影响存在性别差异,女婴较男婴更敏感。目前铊暴露对胎儿生长发育影响的机制尚不明确。有研究表明铊可通过氧化应激方式影响胎盘线粒体功能,干扰酶和激素相关活动,从而影响胎儿生长发育[24]。也有研究发现胎盘对慢性缺氧的反应存在性别差异[25],这可能是孕期铊暴露对不同性别胎儿发育影响不同的原因。

利益冲突: 无

| [1] | Rodríguez-Mercado JJ, Altamirano-Lozano MA. Genetic toxicology of thallium:a review[J]. Drug Chem Toxicol, 2013, 36(3): 369–383. DOI:10.3109/01480545.2012.710633 |

| [2] | Karbowska B. Presence of thallium in the environment:sources of contaminations, distribution and monitoring methods[J]. Environ Monit Assess, 2016, 188(11): 640. DOI:10.1007/s10661-016-5647-y |

| [3] | Peter AL, Viraraghavan T. Thallium:a review of public health and environmental concerns[J]. Environ Int, 2005, 31(4): 493–501. DOI:10.1016/j.envint.2004.09.003 |

| [4] | Hoffman RS, Hoffman R. Thallium poisoning during pregnancy:A case report and comprehensive literature review[J]. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol, 2000, 38(7): 767–775. DOI:10.1081/CLT-100102390 |

| [5] | Xia W, Du XF, Zheng TZ, et al. A case-control study of prenatal thallium exposure and low birth weight in China[J]. Environ Health Perspect, 2016, 124(1): 164–169. DOI:10.1289/ehp.1409202 |

| [6] | Jiang YQ, Xia W, Zhang B, et al. Predictors of thallium exposure and its relation with preterm birth[J]. Environ Pollut, 2018, 233: 971–976. DOI:10.1016/j.envpol.2017.09.080 |

| [7] |

葛星, 徐叶清, 黄三唤, 等. 妊娠期肝内胆汁淤积症对分娩结局影响的出生队列研究[J]. 中华流行病学杂志, 2016, 37(2): 187–191.

Ge X, Xu YQ, Huang SH, et al. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy and fetal outcomes:a prospective birth cohort study[J]. Chin J Epidemiol, 2016, 37(2): 187–191. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2016.02.007 |

| [8] | Liang CM, Li ZJ, Xia X, et al. Determine multiple elements simultaneously in the sera of umbilical cord blood samples-a very simple method[J]. Biol Trace Elem Res, 2017, 177(1): 1–8. DOI:10.1007/s12011-016-0853-6 |

| [9] | Xiao TF, Yang F, Li SH, et al. Thallium pollution in China:A geo-environmental perspective[J]. Sci Total Environ, 2011, 421/42: 51–58. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2011.04.008 |

| [10] | Lee JH, Kim DJ, Ahn BK. Distributions and concentrations of thallium in Korean soils determined by single and sequential extraction procedures[J]. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol, 2015, 94(6): 756–763. DOI:10.1007/s00128-015-1533-5 |

| [11] | Casiot C, Egal M, Bruneel O, et al. Predominance of aqueous Tl(Ⅰ) species in the river system downstream from the abandoned Carnoulès mine (southern France)[J]. Environ Sci Technol, 2011, 45(6): 2056–2064. DOI:10.1021/es102064r |

| [12] | Liu J, Luo XW, Wang J, et al. Thallium contamination in arable soils and vegetables around a steel plant-A newly-found significant source of Tl pollution in South China[J]. Environ Pollut, 2017, 224: 445–453. DOI:10.1016/j.envpol.2017.02.025 |

| [13] | Shao WT, Liu Q, He XW, et al. Association between level of urinary trace heavy metals and obesity among children aged 6-19 years:NHANES 1999-2011[J]. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int, 2017, 24(12): 11573–11581. DOI:10.1007/s11356-017-8803-1 |

| [14] | Curković M, Sipos L, Puntarić D, et al. Detection of thallium and uranium in well water and biological specimens of an eastern Croatian population[J]. Arh Hig Rada Toksikol, 2013, 64(3): 385–394. DOI:10.2478/10004-1254-64-2013-2300 |

| [15] |

余晓丹, 颜崇淮, 沈晓明, 等. 上海市婴幼儿胎儿期重金属暴露水平及危险因素[J]. 中华预防医学杂志, 2011, 45(9): 806–809.

Yu XD, Yan CH, Shen XM, et al. Exposure level and risk factors of heavy metal in prenatal period among Shanghai Infants[J]. Chin J Prev Med, 2011, 45(9): 806–809. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-9624.2011.09.009 |

| [16] | Govarts E, Remy S, Bruckers L, et al. Combined effects of prenatal Exposures to Environmental Chemicals on Birth Weight[J]. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2016, 13(5): 495–513. DOI:10.3390/ijerph13050495 |

| [17] |

邵小翠, 朴丰源, 关怀, 等. 大连地区母血和脐血铊浓度及其相关的影响因素[J]. 癌变·畸变·突变, 2010, 22(2): 119–122.

Shao XC, Piao FY, Guan H, et al. Blood thallium levels of maternal and umbilical cord blood and the related factors in Dalian[J]. Carcinogen, Teratogen Mutagen, 2010, 22(2): 119–122. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1004-616X.2010.02.010 |

| [18] | Fort M, Cosín-Tomás M, Grimalt JO, et al. Assessment of exposure to trace metals in a cohort of pregnant women from an urban center by urine analysis in the first and third trimesters of pregnancy[J]. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int, 2014, 21(15): 9234–9241. DOI:10.1007/s11356-014-2827-6 |

| [19] | Forns J, Fort M, Casas M, et al. Exposure to metals during pregnancy and neuropsychological development at the age of 4 years[J]. Neurotoxicology, 2014, 40: 16–22. DOI:10.1016/j.neuro.2013.10.006 |

| [20] | Hu X, Zheng T, Cheng Y, et al. Distributions of heavy metals in maternal and cord blood and the association with infant birth weight in China[J]. J Reprod Med, 2015, 60(1/2): 21–29. |

| [21] | King JC. Physiology of pregnancy and nutrient metabolism[J]. Am J Clin Nutr, 2000, 71(5 Suppl): 1218S–1225S. |

| [22] | Galván-Arzate S, Pedraza-Chaverrí J, Medina-Campos ON, et al. Delayed effects of thallium in the rat brain:regional changes in lipid peroxidation and behavioral markers, but moderate alterations in antioxidants, after a single administration[J]. Food Chem Toxicol, 2005, 43(7): 1037–1045. DOI:10.1016/j.fct.2005.02.006 |

| [23] | Hall BK. Critical periods during development as assessed by thallium-induced inhibition of growth of embryonic chick tibiae in vitro[J]. Teratology, 1985, 31(3): 353–361. DOI:10.1002/tera.1420310306 |

| [24] | Vriens A, Nawrot TS, Baeyens W, et al. Neonatal exposure to environmental pollutants and placental mitochondrial DNA content:A multi-pollutant approach[J]. Environ Int, 2017, 106: 60–68. DOI:10.1016/j.envint.2017.05.022 |

| [25] | Matheson H, Veerbeek JHW, Charnock-Jones DS, et al. Morphological and molecular changes in the murine placenta exposed to normobaric hypoxia throughout pregnancy[J]. J Physiol, 2016, 594(5): 1371–1388. DOI:10.1113/JP271073 |

2018, Vol. 39

2018, Vol. 39