文章信息

- 段晓楠, 严双琴, 汪素美, 胡晶晶, 方姣, 龚纯, 万宇辉, 苏普玉, 陶芳标, 孙莹.

- Duan Xiaonan, Yan Shuangqin, Wang Sumei, Hu Jingjing, Fang Jiao, Gong Chun, Wan Yuhui, Su Puyu, Tao Fangbiao, Sun Ying.

- 下丘脑-垂体-肾上腺轴昼夜节律指标随青春期发育变化的特征

- Developmental characteristics of circadian rhythms in hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis during puberty

- 中华流行病学杂志, 2018, 39(8): 1086-1090

- Chinese Journal of Epidemiology, 2018, 39(8): 1086-1090

- http://dx.doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2018.08.014

-

文章历史

收稿日期: 2018-02-07

2. 243011 安徽省马鞍山市妇幼保健院

2. Ma'anshan Maternal and Child Health Center, Ma'anshan 243011, China

下丘脑-垂体-肾上腺(hypothalamic-pituitary- adrenal,HPA)轴作为主要的生理应激系统,通过皮质醇分泌调节内源性应激反应,其功能变化有重要的神经内分泌学意义。清晨皮质醇水平在醒后30~40 min迅速增加,形成峰值后逐渐下降,并在近午夜时达最低点而后缓慢增加[1]。当前儿童青少年中HPA轴昼夜节律相关研究多集中于昼夜节律异常与心理病理症状的关联[2-5],而对于HPA轴昼夜节律在青春期发育过程中基本特征尚不清楚[6-9]。理解HPA轴昼夜节律随青春期发育的变化特征,有助于理解青春期多种精神病理症状的高发现象,为预防青少年心理健康问题提供相关信息。本研究采用多时点、复合型指标评价皮质醇昼夜节律,通过收集清晨觉醒时、醒后30 min和晚上入睡时皮质醇,计算皮质醇觉醒应答(cortisol awakening response,CAR)、皮质醇昼夜斜率(durinal cortisol slope,DCS)和昼间皮质醇总分泌量,即皮质醇曲线下面积(the area under the curve relative to ground,AUC),旨在多维度评估HPA轴昼夜节律在不同青春期发育进程的变化特点,为深入研究HPA轴与身心健康关联提供基本证据支持。

对象与方法1.研究对象:2015年10月对安徽省马鞍山市3所小学2~3年级1 070名儿童进行体格检查和第二性征发育评估。2016年和2017年开展体格评估与青春期发育的随访调查,同时进行HPA轴昼夜节律指标的基线与随访调查,收集清晨觉醒时、醒后30 min和晚上入睡时3个时点唾液样本。见图 1。本研究通过了安徽医科大学伦理委员会的审批,调查对象均由其父母签署了知情同意书。

|

| 注:a以实际提供唾液的儿童数量为准 图 1 马鞍山市儿童队列基线与随访调查流程 |

2.研究方法:

(1)基本资料:问卷调查包括性别、出生日期、入睡和起床时间、每周体力活动等信息。体格检查采用机械式身高坐高计测量身高,测量人员平视水平压板读数。测量误差不得超过0.5 cm。采用电子体重计测量体重,使用前校正,测量误差不超过0.1 kg。由与儿童同性别的儿科内分泌专业研究生采用视诊与触诊结合的方法评价青春期发育。

(2)男、女童青春期发育进程的判定:女童乳房发育评价采用Tanner分期法[10],男童采用Prader睾丸体积测量子评价睾丸容积。乳房TannerⅠ期代表未发育,Ⅴ期代表乳房发育达成年人水平,将乳房发育Ⅱ期作为青春期启动的标志。男童睾丸容积4 ml作为青春期启动的标志。根据青春期发育随访结果,将男、女童划分为“持续未发育”(随访期间均未发育)、“开始发育”(基线未发育、随访期发育)、“持续发育”(基线和随访均已发育)。

(3)唾液收集:使用Salivette唾液采集器(德国Sarstedt公司)收集3个时间点的唾液样本,即清晨觉醒时、醒后30 min和晚上入睡时。要求调查对象在每次收集前至少30 min不能刷牙、进食、喝饮料(饮水除外)。收集唾液时将棉棒放在口中咀嚼1 min,直至完全浸入唾液,将棉棒放回管中,次日将唾液管交回调查员。调查员收取唾液管后立即进行离心,并将离心后的唾液样品置于-20 ℃冰箱中保存。

(4)皮质醇检测:采用上海源叶生物科技有限公司唾液皮质醇ELISA试剂盒(批号:20161003)测定皮质醇浓度。所有的操作均按说明书要求进行,具体步骤:①将不同浓度(0、0.75、1.5、3、6及12 nmol/L)的标准品各50 μl依次加入。②样本孔先加待测样本10 μl,再加样本稀释液40 μl;空白孔不加样本也不加稀释液。③除空白孔外,标准品孔和样本孔中每孔加入辣根过氧化物酶(HRP)标记的检测抗体100 μl,用封板膜封住反应孔,37 ℃水浴锅或恒温箱温浴60 min。④弃去液体,吸水纸上拍干,每孔加满洗涤液,静置1 min,甩去洗涤液,吸水纸上拍干,如此重复洗板5次(也可用洗板机洗板)。⑤每孔加入底物A、B各50 μl,37 ℃避光孵育15 min。⑥每孔加入终止液50 μl,15 min内在450 nm波长处检测A值,最后绘制标准曲线计算皮质醇的浓度。

(5)HPA轴昼夜节律评价:根据一天中收集的3个时点的皮质醇浓度样本计算3个HPA轴节律指标:CAR、昼间皮质醇总分泌量、DCS[11-12]。皮质醇觉醒应答反映觉醒后30~40 min内皮质醇分泌的增长;昼间皮质醇分泌总量表示一天中皮质醇的总分泌量的大小,以AUC表示昼间皮质醇总分泌量,使用梯形规则计算[12]。AUC=[(m1+m2)×T1]/2+[(m2+m3)×T2]/2;其中m1~m3表示白天3个时点(早晨觉醒时、醒后30 min和晚上入睡时)收集的唾液皮质醇浓度,T1和T2表示两个唾液收集时点间的时间间隔(h)。DCS反映HPA轴节律一天中的变化幅度。计算2017年与2016年的HPA轴昼夜节律各指标的差值,包括CAR改变值、AUC改变值和DCS差值。

3.统计学分析:采用EpiData 3.0软件进行数据录入,采用SPSS 23.0软件进行统计学分析。年龄服从正态分布,用x±s表示;采用t检验比较年龄在基线与随访期的差异;采用χ2检验比较乳房发育分期与睾丸容积构成比在基线与随访期的差异。HPA轴昼夜节律基线各指标浓度属非正态分布,以M(Q25~Q75)表示。采用Mann-Whitney U检验比较HPA轴昼夜节律指标在基线与随访期差异,采用K个独立样本的Kruskal-Wallis检验HPA轴昼夜节律指标及变化值在青春期不同发育进程组儿童中的差异。

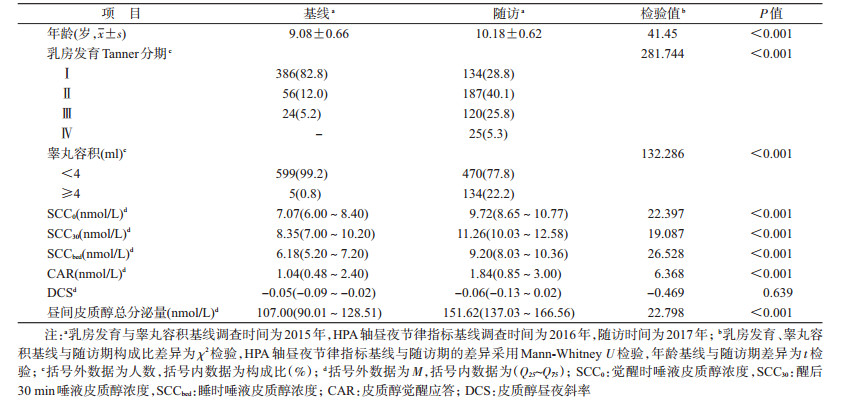

结果1.基本情况:与基线相比,随访结束时觉醒时、醒后30 min和入睡时皮质醇浓度升高,差异有统计学意义(Z值分别为22.397、19.087、26.528,均P<0.01);CAR、昼间皮质醇总分泌量均明显升高,差异有统计学意义(Z值分别为6.368、22.798,均P<0.01);DCS在基线期与随访期的差异无统计学意义(Z=-0.469,P>0.05)。见表 1。

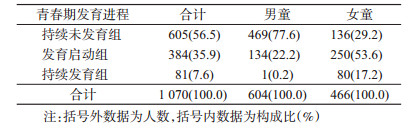

2.男、女童青春期发育进程:根据2015-2017年随访期间青春期发育变化,56.5%(605/1 070)的儿童处于持续未发育阶段;35.9%(384/1 070)的儿童处于青春期发育启动阶段;7.6%(81/1 070)的儿童处于持续发育阶段。见表 2。

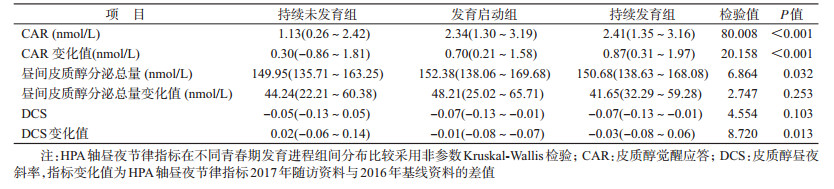

3. HPA轴昼夜节律指标与青春期发育的关系:青春期启动组和持续发育组CAR、CAR变化值高于持续未发育组,差异有统计学意义(CAR:Z值分别为8.551、4.680,均P<0.01;CAR变化值:Z值分别为4.079、2.700,均P<0.01);青春期启动组与持续发育组CAR及CAR变化值差异无统计学意义(Z值分别为0.047、0.925,均P>0.05)。见表 3。

与持续未发育组相比,青春期启动组中昼间皮质醇总分泌量明显升高,差异有统计学意义,持续发育组中差异无统计学意义(Z=2.591,P=0.01;Z=1.618,P=0.106);青春期启动组与持续发育组的差异无统计学意义(Z=0.047,P=0.963)。昼间皮质醇总分泌量变化值在不同青春期发育进程组儿童中差异无统计学意义(χ2=2.747,P=0.253)。

与持续未发育组相比,DCS变化值在青春期启动组和持续发育组中明显降低,差异有统计学意义(Z=-2.450,Z=-2.151,均P<0.05),持续发育组中变化值低于青春期启动组,差异无统计学意义(Z=-0.820,P=0.412)。DCS在不同青春期发育进程组儿童中差异无统计学意义(χ2=4.554,P=0.032)。

讨论本研究基于健康儿童队列,结合一天中多时点唾液收集和青春期第二性征评价,探讨HPA轴昼夜节律指标随青春期发育的变化特征。结果显示,CAR和昼间皮质醇总分泌量随青春期发育启动和进展明显升高,青春期发育启动组和进展组儿童CAR增加值明显高于未发育组,DCS明显低于未发育组。

CAR随青春期发育启动或进展逐渐升高,提示青春期发育可能使HPA轴觉醒后30 min皮质醇分泌量增加。与国外研究不一致,如Oskis等[13]发现月经来潮女童的CAR明显低于月经未来潮女童;Adam[14]报道CAR在青春期已发育青少年中低于青春期未发育的个体。Shirtcliff等[15]认为觉醒后30 min皮质醇水平在青春期可能呈“U”形分布,9~11岁皮质醇水平降低,11岁后皮质醇水平升高。但上述研究均为横断面调查,研究对象年龄范围较大,可能是本研究结果与上述研究结果不一致的原因之一。

昼间皮质醇总分泌量随青春期发育启动而升高,与国外调查结果较为一致。Oskis等[13]发现月经来潮女童中昼间皮质醇总分泌量更高,LeMoult等[16]也提出随着青春期发育进展,昼间皮质醇总分泌量增加。但本研究未发现昼间皮质醇总分泌量变化值在青春期不同发育阶段儿童中的变化,提示青春期发育启动前昼间皮质醇总分泌量可能已经开始增加。

本研究提示DCS随青春期发育而降低,即昼夜皮质醇差值更大,斜率更陡峭,这一结果与Rotenberg等[17]的研究结果不一致,其横断面研究结果显示9~18岁阴毛已发育的青少年DCS更平缓。但阴毛发育与乳房和睾丸发育是青春期发育的不同通路,受不同的神经内分泌过程调控。

目前关于青春期发育对HPA轴昼夜节律影响的机制尚不清楚。Black等[18]在9岁儿童中发现,HPG轴的激素指标脱氢表雄酮和睾酮与皮质醇浓度正相关,提出HPG轴与HPA轴间的正向偶联关系。这一观点进一步支持本研究发现的HPA轴昼夜节律随青春期发育而升高这一结论。

本研究存在局限性。首先课题仅收集了一天中唾液皮质醇评价HPA轴昼夜节律,而未能连续收集2~3 d;其次儿童清晨觉醒时间为自我报告,而非佩戴电子设备的客观监测,可能存在偏倚;第三,研究对象的年龄偏小,纵向随访年限较短,尚不能描述HPA轴昼夜节律指标在青春期发育中、晚期的变化趋势。

综上所述,本研究基于健康儿童群体,为阐明HPA轴昼夜节律随青春期发育的变化模式提供了基线资料,提示青少年特定健康问题与HPA轴功能异常的关联研究中需考虑青春期发育这一重要的影响因素。

利益冲突: 无

| [1] | Stalder T, Kirschbaum C, Kudielka BM, et al. Assessment of the cortisol awakening response:Expert consensus guidelines[J]. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 2016, 63: 414–432. DOI:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.10.010 |

| [2] | McGinnis EW, Lopez-Duran N, Martinez-Torteya C, et al. Cortisol awakening response and internalizing symptoms across childhood:exploring the role of age and externalizing symptoms[J]. Int J Behav Dev, 2016, 40(4): 289–295. DOI:10.1177/0165025415590185 |

| [3] | Adam EK, Vrshek-Schallhorn S, Kendall AD, et al. Prospective associations between the cortisol awakening response and first onsets of anxiety disorders over a six-year follow-up-2013 Curt Richter Award Winner[J]. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 2014, 44: 47–59. DOI:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.02.014 |

| [4] | Dietrich A, Ormel J, Buitelaar JK, et al. Cortisol in the morning and dimensions of anxiety, depression, and aggression in children from a general population and clinic-referred cohort:An integrated analysis.. The TRAILS study[J]. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 2013, 38(8): 1281–1298. DOI:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.11.013 |

| [5] | Nederhof E, Van Oort FVA, Bouma EM, et al. Predicting mental disorders from hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis functioning:a 3-year follow-up in the TRAILS study[J]. Psychol Med, 2015, 45(11): 2403–2412. DOI:10.1017/S0033291715000392 |

| [6] | Doane LD, Mineka A, Zinbarg RE, et al. Are flatter diurnal cortisol rhythms associated with major depression and anxiety disorders in late adolescence? The role of life stress and daily negative emotion[J]. Dev Psychopathol, 2013, 25(3): 629–642. DOI:10.1017/S0954579413000060 |

| [7] | Marceau K, Ruttle PL, Shirtcliff EA, et al. Developmental and contextual considerations for adrenal and gonadal hormone functioning during adolescence:implications for adolescent mental health[J]. Dev Psychobiol, 2015, 57(6): 742–768. DOI:10.1002/dev.21214 |

| [8] | Dantzer R, Kalin NH. The cortisol awakening response at its best[J]. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 2016, 63: 412–413. DOI:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.11.002 |

| [9] | Simons SS, Cillessen AH, de Weerth C. Associations between circadian and stress response cortisol in children[J]. Stress, 2017, 20(1): 52–58. DOI:10.1080/10253890.2016.1276165 |

| [10] | Marshall WA, Tanner JM. Variations in pattern of pubertal changes in girls[J]. Arch Dis Child, 1969, 44(235): 291–303. DOI:10.1136/adc.44.235.291 |

| [11] | Šupe-Domić D, Milas G, Hofman ID, et al. Daily salivary cortisol profile:Insights from the Croatian Late Adolescence Stress Study (CLASS)[J]. Biochem Med, 2016, 26(3): 408–420. DOI:10.11613/BM.2016.043 |

| [12] | Pruessner JC, Kirschbaum C, Meinlschmid G, et al. Two formulas for computation of the area under the curve represent measures of total hormone concentration versus time-dependent change[J]. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 2003, 28(7): 916–931. DOI:10.1016/S0306-4530(02)00108-7 |

| [13] | Oskis A, Loveday C, Hucklebridge F, et al. Diurnal patterns of salivary cortisol across the adolescent period in healthy females[J]. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 2009, 34(3): 307–316. DOI:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.09.009 |

| [14] | Adam EK. Transactions among adolescent trait and state emotion and diurnal and momentary cortisol activity in naturalistic settings[J]. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 2006, 31(5): 664–679. DOI:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2006.01.010 |

| [15] | Shirtcliff EA, Dismukes AR, Marceau K, et al. A dual-axis approach to understanding neuroendocrine development[J]. Dev Psychobiol, 2015, 57(6): 643–653. DOI:10.1002/dev.21337 |

| [16] | LeMoult J, Colich NL, Sherdell L, et al. Influence of menarche on the relation between diurnal cortisol production and ventral striatum activity during reward anticipation[J]. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci, 2015, 10(9): 1244–1250. DOI:10.1093/scan/nsv016 |

| [17] | Rotenberg S, McGrath JJ, Roy-Gagnon MH, et al. Stability of the diurnal cortisol profile in children and adolescents[J]. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 2012, 37(12): 1981–1989. DOI:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.04.014 |

| [18] | Black SR, Lerner MD, Shirtcliff EA, et al. Patterns of neuroendocrine coupling in 9-year-old children:Effects of sex, body-mass index, and life stress[J]. Biol Psychol, 2017, 132: 252–259. DOI:10.1016/j.biopsycho.2017.11.004 |

2018, Vol. 39

2018, Vol. 39