文章信息

- 李慧, 宋璐璐, 申丽君, 刘冰青, 郑小璇, 张莉娜, 李媛媛, 夏玮, 张斌, 周爱芬, 王友洁, 徐顺清.

- Li Hui, Song Lulu, Shen Lijun, Liu Bingqing, Zheng Xiaoxuan, Zhang Lina, Li Yuanyuan, Xia Wei, Zhang Bin, Zhou Aifen, Wang Youjie, Xu Shunqing.

- 母亲身高与早产的相关分析

- Association between maternal body height and risk of preterm birth

- 中华流行病学杂志, 2018, 39(3): 313-316

- Chinese Journal of Epidemiology, 2018, 39(3): 313-316

- http://dx.doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2018.03.012

-

文章历史

收稿日期: 2017-08-05

2. 430030 武汉, 华中科技大学同济医学院公共卫生学院劳动卫生与环境卫生学系;

3. 430030 武汉市妇女儿童医疗保健中心

2. Department of Occupational and Environmental Health, School of Public Health, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan 430030, China;

3. Woman and Children Medical and Healthcare Center of Wuhan, Wuhan 430030, China

早产是指妊娠满28周至不足37周间的分娩[1]。早产是围产儿发病以及死亡的重要原因[2]。早产对儿童生长发育具有长期不利的影响,给家庭和社会带来了巨大的经济负担[3]。因此探索早产的危险因素,有利于医务人员确定早产的高危人群。身高是一个测量简单,容易获得的指标。研究发现身高较矮孕妇的子宫体积较小、骨盆较狭窄[4],易发生宫内生长受限和胎膜早破[5-6],增加早产风险[7]。目前关于身高影响早产风险的机制尚不清楚,研究也多数限于欧美国家且结论不一[8-12]。由于受种族、经济条件等的影响,不同国家间的身高分布存在差异,其他国家人群的研究结论并非适用于我国人群。为此本研究拟通过武汉健康宝贝出生队列探讨身高与早产的关联。

对象与方法1.研究对象:以2012年9月至2014年10月在武汉市妇女儿童医疗保健中心分娩的孕妇为对象建立武汉健康宝贝出生队列。纳入标准为在武汉市居住且产后继续留在该市居住,分娩单胎活产儿并能理解和完成调查问卷内容的孕妇。此期间共有11 311名研究对象进入队列。本次分析排除89例分娩出生缺陷儿的孕妇和身高或其他协变量信息缺失孕妇152例,最终获得11 070名研究对象。所有参与队列的孕妇均签署知情同意书。

2.研究方法:通过面对面问卷调查、查阅保健手册和病历记录收集资料。问卷调查内容主要包括年龄、文化程度、职业、吸烟、饮酒、被动吸烟、体育锻炼等。查阅保健手册和病历记录的内容主要包括妊娠期高血压、妊娠期糖尿病、产次、孕周等。孕前体重为孕妇在第一次产检时回忆获得,并计算孕前BMI。问卷调查由经统一培训考核合格调查员参与。现场质量控制员对每天的问卷进行核查,如有错项或漏项及时标明,由调查员电话回访核实补充。问卷采用平行双录入并核查。

3.相关指标与定义:身高是由专业人员采用身高仪在孕妇第一次产检时按常规方法测定,取值精确到0.1 cm。孕周是依据末次月经确定。早产根据《妇产科学》相关诊断标准定义为妊娠满28周至不足37周的分娩[1]。被动吸烟是指每周至少1次且每次暴露于二手烟时间>15 min。

4.统计学分析:采用SAS 9.4软件。计量资料先进行正态性检验,符合正态分布的计量资料用x±s表示,以t检验进行组间比较;计数资料用频数(百分比)表示,采用χ2检验进行组间比较。由于目前身高较矮还没有标准的界值点,所以根据身高的四分位数将研究对象分为4组(<158、158~、160~以及>164 cm),以身高>164 cm组作参照组。采用logistic回归分析计算身高与早产的OR值和95%CI,身高作为分类变量或连续变量纳入回归模型。为计算身高作为分类变量的线性趋势(趋势P值),以各身高分组的中位数作为连续性变量纳入回归模型。按年龄(<28岁或≥28岁)、孕前BMI(<24 kg/m2或≥24 kg/m2)、文化程度(高中及以下或大学及以上)和产次(初产或经产)进行分层分析,并用Wald检验计算交互作用。排除患妊娠期糖尿病或高血压的孕妇,对身高与早产进行敏感性分析。所有分析采用双侧检验,P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。

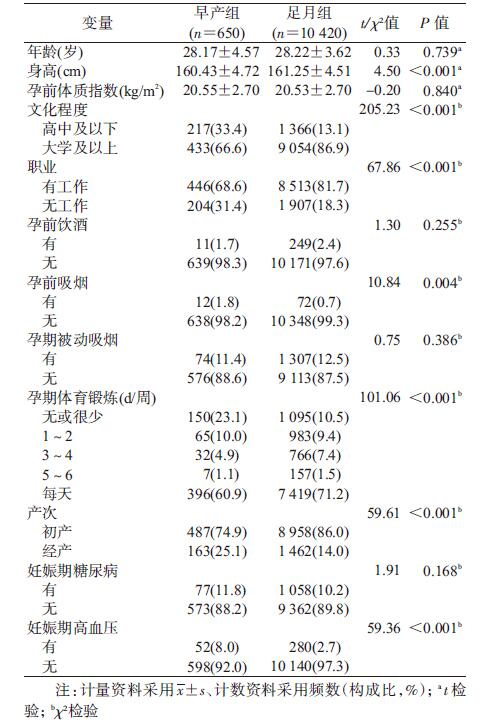

结果1.一般情况:11 070名孕妇年龄(28.22±3.68)岁,孕周(39.08±1.41)周,身高(161.20±4.52)cm,孕前BMI为(20.53±2.70)kg/m2;早产发生率为5.9%(n=650)。表 1显示身高、文化程度、职业、孕前吸烟、孕期体育锻炼、产次、妊娠期高血压在早产组和足月组间分布的差异有统计学意义(P<0.05)。

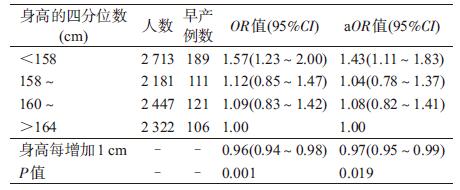

2.身高与早产关系的logistic回归分析:控制可能的混杂因素后,分析显示身高与早产呈负相关(P=0.003),身高<158 cm组发生早产的风险是身高>164 cm组的1.46倍(OR=1.46,95%CI:1.16~1.83)。身高每增加1 cm,早产的风险减少3%(OR=0.97,95%CI:0.95~0.99)。见表 2。

3.身高与早产关系的分层分析:身高与年龄、孕前BMI、文化程度及产次对早产的风险没有交互作用(P for interaction>0.05)。见图 1。

|

| 注:控制年龄、孕前体质指数、文化程度、职业、孕前饮酒、孕前吸烟、孕期被动吸烟、孕期体育锻炼、产次、妊娠期糖尿病以及妊娠期高血压;OR值(95%CI)为身高<158 cm组相对于>164 cm组早产风险,方块代表OR值,横线代表 95%CI 图 1 孕妇身高与早产关系的分层分析 |

4.身高与早产关系的敏感性分析:排除1 407例患妊娠期糖尿病或高血压的孕妇后,身高与早产的负相关关系依然存在(P for trend=0.019)。见表 3。

本研究利用武汉健康宝贝出生队列的大样本数据,分析母亲身高与早产的关系。研究结果显示,身高与早产的风险呈负相关。

本研究发现身高较矮的孕妇早产风险增加,与以往文献报道一致[8-10]。Shachar等[8]分析美国加利福尼亚1 655 385条出生登记信息后发现自报的母亲身高与早产呈负相关且独立于孕前BMI。瑞典一项研究纳入192 432名孕妇(其中部分身高信息为自我报告),发现身高≤155 cm的孕妇早产风险是身高≥179 cm的2.07倍[10]。但也有研究并未发现身高和早产的关系[11-12]。美国一项孕期感染和营养研究纳入2 319名孕妇,调查发现身高和早产无相关性[12]。上述研究结果的差异可能是由于种族间身高差异、身高分组不同及样本量大小造成的。

亚组分析显示在年龄<28岁、孕前BMI<24 kg/m2和初产妇组中,身高较矮对早产的影响更大。可能的原因是年龄较大、孕前BMI较大和经产妇是早产的高危人群,更有可能具有早产的其他危险因素,并可能掩盖了身高对早产的作用。研究发现身高与妊娠期糖尿病和高血压有关[13-14],且增加早产风险。排除这两种疾病的敏感性分析显示,身高与早产的负相关关系依然存在,说明结果的稳定性。

儿童期的社会经济和营养状况是影响成年期身高的重要因素[15-16]。研究发现儿童期不良的经济状况或营养不足会增加今后的早产风险[17-18]。由于成年期的文化程度可能间接反映儿童期的经济状况[19],本研究在回归模型中控制了文化程度,发现身高与早产依然呈负相关关系,表明儿童期的经济状况可能并不能完全解释身高与早产的关系。

本研究存在局限性。首先未区别早产类型(自发性和医源性早产),因此不能分析身高和各种早产类型的关系;其次研究中虽控制了较多的混杂因素,但未收集到如母亲儿童期营养状况和孕期膳食营养等与早产有关的混杂因素,可能会导致一定的残余混杂。

综上所述,本研究发现身高较矮的孕妇早产风险增加。因此对该类人群应加强监测,预防和降低早产的发生风险。

利益冲突: 无

| [1] |

谢幸, 苟文丽. 妇产科学[M]. 8版. 北京: 人民卫生出版社, 2013.

Xie X, Gou WL.Obstetrics and gynecology[M]. 8th ed. Beijing: People's Medical Publishing House, 2013. |

| [2] | Liu L, Johnson HL, Cousens S, et al. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality:an updated systematic analysis for 2010 with time trends since 2000[J]. Lancet, 2012, 379(9832): 2151–2161. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60560-1 |

| [3] | Morken NH. Preterm birth:new data on a global health priority[J]. Lancet, 2012, 379(9832): 2128–2130. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60857-5 |

| [4] | Özaltin E, Hill K, Subramanian SV. Association of maternal stature with offspring mortality, underweight, and stunting in low-to middle-income countries[J]. JAMA, 2010, 303(15): 1507–1516. DOI:10.1001/jama.2010.450 |

| [5] | Zhang X, Cnattingius S, Platt RW, et al. Are babies born to short, primiparous, or thin mothers "normally" or "abnormally" small?[J]. J Pediatr, 2007, 150(6): 603–607. DOI:10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.01.048 |

| [6] | van Roosmalen J, Brand R. Maternal height and the outcome of labor in rural Tanzania[J]. Int J Gynaecol Obstet, 1992, 37(3): 169–177. DOI:10.1016/0020-7292(92)90377-U |

| [7] | Goldenberg RL, Culhane JF, Iams JD, et al. Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth[J]. Lancet, 2008, 371(9606): 75–84. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60074-4 |

| [8] | Shachar BZ, Mayo JA, Lee HC, et al. Effects of race/ethnicity and BMI on the association between height and risk for spontaneous preterm birth[J]. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 2015, 213(5): 700–700.e9. DOI:10.1016/j.ajog.2015.07.005 |

| [9] | Smith GCS, Shah I, White IR, et al. Maternal and biochemical predictors of spontaneous preterm birth among nulliparous women:a systematic analysis in relation to the degree of prematurity[J]. Int J Epidemiol, 2006, 35(5): 1169–1177. DOI:10.1093/ije/dyl154 |

| [10] | Derraik JGB, Lundgren M, Cutfield WS, et al. Maternal height and preterm birth:a study on 192, 432 Swedish women[J]. PLoS One, 2016, 11(4): e0154304. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0154304 |

| [11] | Meis PJ, Michielutte R, Peters TJ, et al. Factors associated with preterm birth in Cardiff, Wales:Ⅱ. Indicated and spontaneous preterm birth[J]. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 1995, 173(2): 597–602. DOI:10.1016/0002-9378(95)90288-0 |

| [12] | Savitz DA, Dole N, Herring AH, et al. Should spontaneous and medically indicated preterm births be separated for studying aetiology?[J]. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol, 2005, 19(2): 97–105. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-3016.2005.00637.x |

| [13] | Brite J, Shiroma E, Bowers K, et al. Height and the risk of gestational diabetes:variations by race/ethnicity[J]. Diabet Med, 2014, 31(3): 332–340. DOI:10.1111/dme.12355 |

| [14] | Antwi E, Groenwold RHH, Browne JL, et al. Development and validation of a prediction model for gestational hypertension in a Ghanaian cohort[J]. BMJ Open, 2017, 7(1): e012670. DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012670 |

| [15] | Bjerregaard P. The Greenland Population Study Group. Childhood conditions and education as determinants of adult height and obesity among Greenland Inuit[J]. Am J Hum Biol, 2010, 22(3): 360–366. DOI:10.1002/ajhb.20999 |

| [16] | Perkins JM, Subramanian SV, Smith GD, et al. Adult height, nutrition, and population health[J]. Nutr Rev, 2016, 74(3): 149–165. DOI:10.1093/nutrit/nuv105 |

| [17] | Miller GE, Culhane J, Grobman W, et al. Mothers' childhood hardship forecasts adverse pregnancy outcomes:role of inflammatory, lifestyle, and psychosocial pathways[J]. Brain Behav Immun, 2017, 65: 11–19. DOI:10.1016/j.bbi.2017.04.018 |

| [18] | Bloomfield FH. How is maternal nutrition related to preterm birth?[J]. Annu Rev Nutr, 2011, 31(1): 235–261. DOI:10.1146/annurev-nutr-072610-145141 |

| [19] | Blane D, White I, Morris J.Education, social circumstances and mortality[M]. Health and Social Organisation, 1996. |

2018, Vol. 39

2018, Vol. 39