文章信息

- 中华预防医学会, 中华预防医学会疫苗与免疫分会.

- Chinese Preventive Medicine Association, Vaccine and Immunology Branch of Chinese Preventive Medicine Association.

- 肺炎球菌性疾病免疫预防专家共识(2017版)

- Expert consensus on immunization for prevention of pneumococcal disease in China (2017)

- 中华流行病学杂志, 2018, 39(2): 111-138

- Chinese Journal of Epidemiology, 2018, 39(2): 111-138

- http://dx.doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2018.02.001

-

文章历史

收稿日期: 2018-01-03

肺炎球菌性疾病(pneumococcal disease, PD)是全球严重的公共卫生问题之一。肺炎链球菌(Streptococcus pneumoniae, Spn)是引起儿童肺炎、脑膜炎、菌血症等严重疾病的主要病原菌, 也是引起急性中耳炎(acute otitis media, AOM)和鼻窦炎等的常见病因。据WHO估算, 2008年全球约有880万<5岁儿童死亡, 其中约47.6万名死于Spn感染, 且发展中国家Spn感染的发病率和死亡率远高于工业化国家, 其中大多数死亡发生在非洲和亚洲[1]。Spn也是引起中国婴幼儿和老年人发病和死亡的重要病因[2-6]。全球<5岁儿童PD病例数最高的10个国家全部位于非洲和亚洲, 占全球总病例数的66%, 而中国位列第二, 占全球总病例数的12%[1]。WHO将可用疫苗预防的疾病进行分级, 其中PD和疟疾为需“极高度优先(very high priorities)”使用疫苗预防的疾病[7]。本文在WHO关于“肺炎球菌疫苗立场文件(2012年)”的基础上, 结合国内外研究的最新进展, 对PD的病原学、临床学、流行病学、疾病负担、疫苗学等方面进行系统综述, 通过PD相关知识的全面系统介绍, 提高专业人员PD防控水平; 在发挥疫苗最佳预防作用与科学使用疫苗方面, 为预防保健和预防接种人员提供相关证据。

一、病原学1881年Sternberg和Pasteur分离并培养出肺炎球菌, 1886年Fraenkel将其命名为肺炎球菌(Pneumococcus)。1920年命名为肺炎双球菌(Diplococcus pneumoniae)。1974年正式命名为肺炎链球菌(Spn)[8]。

1.生物学性状:Spn呈矛头状, 有单个存在, 或成双或短链状排列。有荚膜, 革兰染色阳性。兼性厌氧, 营养要求高, 在含有血液或血清的培养基中才能生长。Spn的抗原主要有荚膜多糖和C多糖(即M蛋白)两种菌体抗原, 荚膜多糖为重要的毒力因子。根据荚膜多糖的组成差异, Spn可分为多种血清型, 目前有丹麦血清分型系统和美国血清分型系统。丹麦血清分型系统基于不同型别菌株之间的交叉反应, 所以具有血清型交叉反应的型别归类为共同的血清群, 同一血清群不同的血清型用数字后面的字母表示, 目前共发现有90多个血清型[9]。而美国血清分型系统中, 血清型是根据发现的先后顺序进行命名的。Spn抵抗力较弱, 对一般消毒剂敏感, 荚膜菌株在干痰中可存活1~2个月。

2.致病机制:Spn是一种重要的条件致病菌, 寄生在健康人鼻咽部。正常情况下并不致病, 当寄生的环境发生变化时, 如机体抵抗力下降时, 麻疹、流感等呼吸道病毒感染以后, 或营养不良、老年体弱等情况下, Spn将透过黏膜防御体系发生侵袭性感染[10-11], 可进入下呼吸道引起肺炎, 可穿过血脑屏障引起细菌性脑膜炎, 也可穿过肺泡上皮细胞、侵袭血管内皮细胞进入血液引起菌血症, 还可从鼻咽部移行进入鼻窦, 引起鼻窦炎, 通过咽鼓管进入中耳, 引起中耳炎。Spn致病过程包括黏附、炎症反应、细菌产物的细胞毒作用[12]。研究表明, Spn的荚膜多糖是致病主要毒力因子, 不同荚膜血清型的Spn存活能力及致病力也不同, 这与补体成分在荚膜上的沉积、降解以及巨噬细胞的清除作用相关。荚膜一方面允许补体C3b的沉积, 阻止其降解为C3d, 而易被巨噬细胞上的C3b受体捕获而被迅速吞噬清除, 只能引起较弱的免疫反应。另一方面C3b降解为C3d, C3d不被巨噬细胞上的C3b受体捕获, 从而诱导较强的抗体反应[13]。此外, Spn的一些蛋白质作为炎症介质或直接攻击宿主组织而在致病过程中也起到重要作用, 如溶血素、自溶酶、Spn表面蛋白A、Spn表面黏附素A、神经氨酸酶等[12, 14]。Spn侵袭宿主细胞的信号传导、自然转化等机制在致病过程中扮演重要角色。相关调查也表明, 大气污染、暴露于吸烟环境、病毒感染等因素, 也与Spn的致病有密切关系[15]。

抗荚膜多糖的抗体具有保护作用。Spn感染后, 可建立型特异性免疫。自然康复取决于机体产生荚膜多糖型特异性抗体, 发病后5~6 d就可形成。荚膜与相应抗体结合后易被吞噬, 某些型别荚膜能激活补体, 对杀灭细菌有意义[16]。

3.实验室检查:通过Spn培养进行实验室诊断。主要应用荚膜肿胀试验、胆汁溶解试验和奥普托欣试验来鉴定菌株, 分子分型用聚合酶链式反应(polymerase chain reaction, PCR)和荧光定量PCR方法以及脉冲场凝胶电泳(pulsed field gel electrophoresis, PFGE)、多位点序列分型(multilocus sequence typing, MLST)、多位点可变数目串联重复序列分析(multiple-locus variable number tandem repeat analysis, MLVA)等[17]。血清分型抗体采用酶联免疫吸附试验(enzyme linked immunosorbent assay, ELISA)和体外调理吞噬试验(opsonophagocytic assay, OPA)方法[18-20]。

二、临床学1.PD:根据Spn感染部位不同, 可分为侵袭性肺炎球菌性疾病(invasive pneumococcal disease, IPD)和非侵袭性肺炎球菌性疾病(non-invasive pneumococcal disease, NIPD)两大类。IPD是指Spn侵入原本无菌的部位和组织所引发的感染, 主要包括脑膜炎、菌血症和菌血症性肺炎等[21]。NIPD即Spn感染到原本与外环境相通的部位所引起的疾病, 主要包括AOM、鼻窦炎和非菌血症性肺炎等。Taylor等[21]回顾文献显示, Spn可以导致95种少见的IPD感染, 包括骨髓炎、心包炎、心内膜炎、腹膜炎、化脓性关节炎、胰腺脓肿、肝脓肿、牙龈感染、腹股沟淋巴结炎、卵巢脓肿、睾丸脓肿、坏死性筋膜炎、溶血尿毒症综合征(hemolytic uremic syndrome)等。华-佛综合征(Waterhouse-Friederichsen syndrome)也可由Spn感染引起。21世纪初, 由Spn导致的儿童坏死性肺炎病例有增多现象[22]。

2.临床诊断:PD的临床诊断依据主要是从感染部位分离出Spn[23], 但获得确定的病原学依据较为困难, 其原因包括:抗生素广泛使用造成病原菌的分离率大大降低; NIPD不伴有菌血症, 血液培养难有阳性结果; 由于Spn常在上呼吸道定植, 因此呼吸道标本的细菌培养结果容易受到干扰, 虽然深部呼吸道标本的细菌培养可以确诊, 但需要侵入性操作(如肺穿刺等), 患儿或家长难以接受[24]。此外, 部分基层医疗机构不具备病原菌培养和分离所需的条件, 也使得PD的临床诊断难度加大。从临床感染类型或症状体征无法准确区分Spn与其他细菌感染。

3.治疗:PD的临床治疗过程中首要考虑的是选择敏感抗生素。开始抗生素治疗前, 应尽可能采集血标本等进行病原学检查。但Spn对常用抗生素可产生耐药性, 且部分地区Spn耐药率呈逐年增长趋势[25-26], 使得临床治疗难度大大增加。经验性选择抗生素治疗PD时应考虑临床感染类型、给药途径和耐药性流行特点。

4.抗菌药物的耐药性:目前PD的临床治疗过程中, 抗生素治疗是首选。然而, Spn对常用抗菌药物, 如青霉素类、大环内酯类、喹诺酮类、头孢菌素和复方新诺明等, 可产生明显的耐药性, 已成为全球性的严峻问题。随着大规模肺炎球菌疫苗接种的引进, 在部分发达地区Spn耐药菌株已有所减少[1], 但在抗生素广泛应用、耐药克隆大量传播而结合疫苗应用较少的许多亚洲国家, Spn的耐药现象仍很严重[26]。

我国流行病学研究表明, 儿科Spn耐药性日益严峻。2006-2007年, 从全国4家儿童医院<5岁肺炎住院患儿中分离到的Spn, 对青霉素的不敏感率为86%, 对头孢曲松和头孢呋辛的不敏感率分别为24.7%和81.0%, 其相对于2000-2002年的不敏感率显著增加[27]。浙江省一项研究对2011-2015年下呼吸道感染学龄前儿童痰标本分离出的Spn耐药性进行回顾性分析, 发现Spn对青霉素G、红霉素、头孢呋辛、头孢曲松、头孢噻肟、头孢吡肟、克林霉素、复方新诺明、阿莫西林/克拉维酸等抗菌药物的耐药率均呈逐年增长趋势[28]。2010-2011年我国10个城市13家医院临床分离的非重复Spn的耐药性研究显示, 从≤5岁儿童中分离的Spn对口服青霉素、注射用青霉素、阿莫西林/克拉维酸、头孢呋辛、头孢曲松、头孢克洛、磺胺甲恶唑/甲氧苄啶的耐药率分别为73.0%、89.3%、47.5%、88.5%、36.9%、88.5%、73.7%, Spn对≤5岁儿童组的耐药率显著高于其他年龄组[29]。重庆市一项研究, 将儿童侵袭性Spn耐药性与非侵袭性Spn耐药性进行对比, 发现侵袭性菌株对红霉素、青霉素、美罗培南、头孢噻肟、克林霉素等的不敏感率显著高于非侵袭性菌株[30]。北京儿童医院研究发现, 肺炎球菌疫苗覆盖的菌株耐药性比非PCV覆盖的菌株耐药性高, 19A的耐药性最高[31]。

此外, 我国Spn对常用抗菌药物的交叉耐药和多重耐药发生率高。2012年亚太地区病原体耐药监测网络数据显示, Spn在亚洲地区总体多重耐药比例为59.3%, 而在中国的多重耐药比例高达83.3%[32]。2013-2014年, 北京儿童医院一项研究发现, 住院患儿Spn对3种抗菌药物的多重耐药率为12.8%, 对4种抗菌药物的多重耐药率为78.1%, 对5种抗菌药物的多重耐药率为2.1%, 总体多重耐药比例达93.0%[25]。

三、流行病学1.传染源、传播途径、易感人群:Spn广泛分布于自然界, 人类是其唯一宿主。Spn常临时定殖于人类鼻咽部[33], 婴幼儿是主要的储存宿主。在中国<5岁健康或上呼吸道感染儿童中, 鼻咽拭子Spn分离率可达20%~40%[34]。Spn在人与人之间传播, 一般经由呼吸道飞沫传播或由定植菌导致自体感染。Spn感染的危险性随年龄、基础疾病、生活环境等不同而具有较大的差异。婴幼儿和老年人感染的危险性相对较高。

儿童易感人群和危险因素包括:①年龄<2岁[2], 其发病率远高于其他年龄段人群(据2012年WHO立场文件报道, 平均75%的IPD病例和83%的Spn脑膜炎病例发生在<2岁儿童, <2岁儿童不同年龄组的病例分布也存在较大差异, 8.7%~52.4%的肺炎病例发生于<6月龄婴儿[1]; 丹麦一项研究住院率与围产期风险因素关系时发现, 在<2岁儿童中, 早产儿、低出生体重儿童或具有出生缺陷的儿童PD住院率最高[35]); ②处于托幼机构等集体单位; ③患有镰状细胞病(sickle cell disease, SCD)、HIV(human immunodeficiency virus)感染、慢性心肺病等[36]; ④人工耳蜗植入者或脑脊液漏[36]; ⑤早产儿、低出生体重儿、缺少母乳喂养、营养缺乏儿童以及室内空气污染等[1, 35, 37]; ⑥暴露于吸烟环境及多子女的家庭是健康儿童IPD的危险因素[38]。

成年人易感人群和危险因素包括年龄>65岁[39-40]和19~64岁同时伴有①慢性疾病:慢性呼吸道疾病, 尤其是慢性阻塞性肺疾病(chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, COPD)和哮喘患者罹患IPD的风险更高; 慢性心脏病, 并随心脏病严重程度的增加而增加; 糖尿病, 血糖水平越高, Spn的感染危险越高, 同时糖尿病也是Spn感染进展为菌血症的一个独立危险因素; 慢性肝病和肝硬化、慢性肾功能衰竭、肾病综合征[41]; ②免疫功能受损者(HIV感染, 血液肿瘤、泛发性恶性肿瘤, 功能性或解剖性无脾者、脾功能障碍、器官和骨髓移植受者)和免疫抑制药物应用[42-45], 再发的IPD在健康人群中并不常见, 但处在严重免疫缺陷状态者则可能随时发生[46]; ③人工耳蜗植入者或脑脊液漏; ④吸烟和酗酒, 其中吸烟可能是具有免疫能力的成年IPD患者最大的独立危险因素, 并存在剂量反应关系, 吸烟可能导致口腔产生Spn定殖, 随着年吸烟量的增加IPD风险也增加[47-50]; ⑤反复发作呼吸道感染、吞咽障碍、咳嗽反射减退; ⑥医源性因素, 如气管插管、气管切开、呼吸机应用、鼻饲管和H2受体阻滞剂的应用、抗生素及激素的不合理应用等; ⑦近期感染流感病毒以及其他呼吸道病毒。流感及大气污染也与PD的感染率具有相关性, 研究发现流感季节成年人IPD发生率明显增高, 且临床表现显著加重; 大气污染(如臭氧、一氧化氮)与IPD感染情况呈显著的相关性[37]。季节性流感和社区获得性肺炎(community acquired pneumonia, CAP)之间的关系不清楚[51-52], 但有报告指出肺炎是大流行性流感的常见并发症[53]。

2.疾病负担:在疫苗使用前, PD是<5岁儿童和>65岁老年人以及有基础疾病人群的常见疾病, 也是导致这些人群死亡的重要原因, 其危害已成为严重的公共卫生问题。因此, WHO将PD和疟疾列为需“极高度优先”使用疫苗预防的疾病。

(1) 全球疾病负担:据WHO估计, 2002年全球<5岁儿童疫苗可预防死因中PD占28%, 位居首位[54]。2008年全球<5岁儿童死亡中5%归因于Spn[55]。2010年全球<5岁儿童肺炎病例中, Spn肺炎258.5万例(18.3%), 死亡41.1万例(32.7%); 西太区<5岁儿童肺炎病例中, Spn肺炎26.3万例(18.4%), 死亡2万例(32.8%)[56]。全球疾病负担工作组估计[57], 2016年全球Spn脑膜炎死亡23 100(95%CI:18 700~30 900)例, 死亡率为0.3/10万(95%CI:0.3/10万~0.4/10万), 损失生命年为126.84万(95%CI:99.62万~172.15万)。

在疫苗接种前时代, IPD全球分布情况, 欧洲<2岁儿童PD发病率为44.4/10万[58], 非洲国家<2岁儿童PD发病率为60/10万~797/10万[59-61], 发病率高于欧洲。

IPD有年龄相关的易感性, 主要侵犯6月龄至2岁儿童。在美国引入7价肺炎球菌结合疫苗(7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, PCV7)之前, <5岁儿童中, Spn每年导致大约1.7万例IPD, 包括700例脑膜炎和200名儿童死亡。6~11月龄儿童IPD的发病率最高, 为235/10万, 2~4岁下降为35.2/10万, 5~17岁年龄儿童发病率最低(3.9/10万)[46]。加拿大报道的各年龄段发病率与美国大体相同, 最年幼儿童发病率相对较低, 而6~17月龄发病率最高, 达到161.2/10万[62]。欧洲<2岁儿童发病率最高(以7月龄至1岁最高), 2岁以后发病率稳步下降[63-64]。

Spn肺炎也是成年人肺炎最常见的临床表现。在欧洲和美国, 约30%~50%成年人CAP住院病例与Spn感染有关。

无明确感染部位的菌血症是美国<2岁儿童中最常见的IPD, 约占70%。在<2岁儿童IPD中, 有菌血症的肺炎占12%~16%[65]。欧美国家研究显示, 50%~90%的菌血症是由Spn引起[66-68]。

WHO估计, 2015年全球下呼吸道感染伤残调整生命年(DALY)占总疾病负担的5.34%, 在各病因中位列第二; 脑膜炎DALY占总疾病负担的0.87%[69]。全球疾病负担研究结果显示, Spn肺炎和Spn脑膜炎DALY在下呼吸道感染和脑膜炎中约占四分之一[70-71]。

伴随着疾病负担的是因健康和生产力损失而造成的沉重的直接和间接经济负担。例如, 美国2010年研究估计, ≥50岁的美国成年人中, 每年由PD产生的直接和间接总成本分别为37亿美元和18亿美元[72]; 加拿大2003年研究估计, 6月龄至9岁儿童的PD带来的社会总成本为1.25亿加元, 其中84%来自中耳炎[73]。

(2) 中国疾病负担:我国关于PD疾病负担的系统研究较少。根据WHO的估计及其他一些研究, 也能反映中国PD的疾病负担较重。

WHO最近估计, 2015年中国<5岁儿童PD严重病例21万余例, 死亡约7 000例; 其中Spn肺炎严重病例数近20万例, 病死率为1%, 死亡率为6.43/10万; Spn脑膜炎8 000余例, 病死率为13%, 死亡率为1.35/10万; 其他严重病例近万例, 病死率为10%, 死亡率为1.21/10万。全球疾病负担工作组估计[57], 2016年中国Spn脑膜炎死亡606.4(95%CI:445.9~862.2)例, 病死率为0.04/10万(95%CI:0.03/10万~0.06/10万), 损失生命年5.23万(95%CI:4.15万~6.54万)。

据2015年中国卫生统计年鉴显示, 2014年全国肺炎出院人数为187.3万, 病死率为0.64%;出院病例中, <5岁儿童占63%, ≥60岁老年人占16.7%[74]。宁桂军等[75]在甘肃省白银市调查显示, <5岁儿童肺炎发病密度估计为0.074/人年, 其中0岁组最低(0.044/人年)、1岁组最高(0.088/人年)。

我国缺少全国性和全人群的PD监测数据。系统评价显示, <5岁儿童肺炎病例中Spn检出率为5.2%~11.0%[76], Spn也是老年人肺炎的主要病原[77-78]。

孙谨芳等[4]研究估计, 中国2010年<1岁儿童Spn脑膜炎发病率为9.21/10万, 病死率为6.23%;1~4岁Spn脑膜炎发病率为5.56/10万, 病死率为4.26%。据死因监测系统估计[79], 2013年全国Spn脑膜炎死亡1 787(95%CI:1 474~2 023例)例。细菌性脑膜炎幸存者中, 15%~30%留有神经后遗症[80-82], 包括智力迟钝、脑瘫、听力丧失和惊厥[83]。

根据中国台湾地区全民健康保险医疗统计[84]和死因统计[85], 2006-2015年<5岁儿童年平均菌血症为4 786例(包括住院、门诊和急诊), 发病率为469/10万, 死亡6人, 病死率为0.128%。8.5%的儿童菌血症是由Spn引起的[86]。

2008-2013年唐山市0~3岁儿童AOM的患病率为56.3%, 4~6岁为29.2%[87]。2013年唐山市173例上呼吸道感染并发AOM患儿中, Spn检出率为10.37%[88]。2014年西安市290例儿童AOM分泌物中, Spn检出率为18.73%[89]。

我国的下呼吸道感染和脑膜炎疾病负担低于全球平均水平, 但是全球疾病负担研究结果显示, 2015年我国下呼吸道感染死亡和早死仍列前10位病因[90]。2015年我国下呼吸道感染DALY占总疾病负担的1.40%, 脑膜炎DALY占总疾病负担的0.15%;Spn脑膜炎DALY在脑膜炎中约占16.46%(DALY率5.95/10万), 占总疾病负担的0.02%;Spn肺炎数据未见报告[90]。

目前我国PD总体经济负担的研究数据缺乏, 但一些研究估计了全因肺炎和脑膜炎的医疗费用[91-95], 其费用资料多数来自医院诊疗记录或医保记录回顾。研究显示, 不同地区费用有明显差异, 脑膜炎医疗费用远远高于肺炎, 且<2岁儿童和>50岁成年人费用相对较高。复旦大学根据全国医保中心数据估计, 2008-2010年我国因肺炎住院的次均总费用分别为7 650、6 598和6 545元; 不同地区、不同医保支付系统中肺炎治疗费用有明显差距, 省会城市与直辖市的住院总费用是全国平均水平的3.48倍。上海市数据显示[94], 2011年肺炎患者平均住院日为13.0 d, 住院次均总费用为10 971元, 患者平均住院日和费用数据呈U形分布, 即<2岁儿童和>50岁成年患者例数和治疗费用明显高于其他人群; 其中<12月龄儿童住院次均费用为8 918元, 12~23月龄为7 385元, 50~64岁为10 160元, ≥65岁为14 520元, 而24月龄至34岁均低于7 000元。此外, 2011年上海市脑膜炎患者平均住院日为22.63 d, 次均费用为23 322元; 各年龄段平均住院日及费用均明显高于肺炎患者, 而低龄儿童及老年人住院费用相对较高, 其中<12月龄儿童次均费用为23 823元, 12~23月龄为28 679元, 24~35月龄为35 651元, ≥65岁为34 495元。北京市和珠海市的CAP调查结果与上海市有差别, 但直接医疗费用均超过万元[92-93]。2011年1月至2012年3月北京市东城区一项样本医院调查显示, 成年人CAP病例平均直接医疗费用为11 119.37元, 包括本人及家属误工、交通、护工的总费用为12 147.97元, 费用与年龄呈正相关[93]。2012年8月至2014年7月珠海市一项哨点医院调查显示, CAP患者平均直接医疗费用为12 701.19元, 总费用为16 091.50元[92]。2012年中国CDC在黑龙江省、河北省、甘肃省和上海市的4个镇开展的社区人群问卷调查显示, <5岁儿童临床诊断肺炎的平均直接医疗费用为5 722元, 费用中位数为3 549元; 其中<12月龄和12~23月龄费用中位数相对较高, 分别为3 900元和4 024元[91]。

我国对实验室确诊的PD医疗费用有两项研究。2005-2009年上海市儿童医院共诊断27例<18岁IPD患者, 其中0~1岁占48.15%, 2~4岁占37.04%, ≥5岁仅占14.81%;平均住院日为20.48 d, 平均治疗费用为18 517.39元; 而Spn败血症、脑膜炎和肺炎患者平均医疗费用分别为22 143.88、28 899.48和4 295.65元[94]。中国CDC急性脑炎脑膜炎监测研究显示, 2006年9月至2014年12月在山东省济南市、湖北省宜昌市和河北省石家庄市的哨点医院共诊断69例Spn脑膜炎, 人均直接医疗费用为4.32万元, 直接非医疗费用为1.00万元, 总直接费用为5.32万元; 总间接费用为1.06万元; 总费用为6.38万元[96]。我国台湾地区研究估计, 2010年≥50岁成年人中PD的直接医疗费用达34亿新台币, 其中肺炎住院费用占比超过90%[97]。

3.血清型分布:Spn致病血清型分布在地理区域、年龄和临床表现上有一定差异, 但是从系统评价研究的结果来看, 现有各种疫苗所包含的血清型覆盖了包括我国在内各地大多数致病的血清型, 其中PCV7覆盖约60%, 10价肺炎球菌结合疫苗(PCV10)覆盖约70%, 13价肺炎球菌结合疫苗(PCV13)覆盖约80%, 23价肺炎球菌多糖疫苗(23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine, PPV23)覆盖>85%。

(1) 全球血清型分布:Johnson等[98]1980-2007年文献系统回顾表明, Spn致病血清型分布随地理区域、年龄和临床表现不同而有差异。全球<5岁儿童约70%的IPD是由6~11种血清型所致, 最常见血清型是1、5、6A、6B、14、19F和23F。在WHO各区域中, 1、5和14型导致的IPD在全球占28%~43%, 在20个最贫困国家中约占30%;19F和23F导致的IPD在全球占9%~18%。在欧洲、北美洲和大洋洲, 18C型也很常见。在纳入各国免疫规划之前, PCV7在全球各区域<5岁儿童IPD中的血清型覆盖率为49%~82%, PCV10为70%~84%, PCV13为74%~88%。

2006-2007年美国<5岁儿童中63%的IPD是由PCV13中包含但PCV7中不包含的6种血清型引起的[99]。19A血清型的增加尤其必要, 因为其似乎已成为美国最常引起IPD的替代血清型(非PCV7血清型)[100]。2010年美国将PCV13纳入儿童常规免疫程序, 对8家儿童医院的监测显示, 在住院的儿童中因血清型19A导致的IPD减少了58%;但19A仍然是最常分离出的血清型[101]。

Iroh等[102]系统评价2000-2015年非洲儿童IPD血清型显示, IPD发病率为62.6/1 000人年, PCV10和PCV13覆盖率分别为66.9%和80.6%。

在PCV7上市前, PPV23所包含的23个血清型覆盖了美国和一些工业化国家中约85%~90%的成年人IPD[1]。1996-2005年英国的监测显示, 在PCV7上市前, >5岁的IPD病例中, PPV23的血清型覆盖率为92%[103]。2000-2006年捷克基于实验室的IPD监测有相似发现, PPV23的血清型覆盖率在各年龄组无明显差别, 全人群血清型覆盖率为86.1%[104]。

(2) 中国血清型分布:1980-2008年我国文献的系统回顾研究认为[105], 14、19A和19F型是我国<5岁儿童肺炎和脑膜炎病例中最常见的血清型, PCV7可覆盖<5岁儿童约79.5%的血清型。

韦宁等[106]对我国PD血清型分布的系统评价显示, ≤18岁人群疫苗血清型覆盖情况为:1996-2004年PCV7为59.5%, PCV13为75.7%;2005-2013年PCV7为60.2%, PCV13为84.8%。≤5岁人群侵袭性菌株疫苗血清型覆盖情况为:PCV7为60.2%, PCV13为87.7%, PCV13可提供更高的覆盖率。傅锦坚等[107]系统评价我国内地健康儿童鼻咽部携带Spn及其血清型的分布显示, Spn携带率为21.7%;PCV7覆盖携带者血清型的47.3%, PCV13为64.1%。

Lyu等[108]系统评价2006-2016年我国Spn血清型分布, 最主要的血清型为19F、19A、23F、14和6B型。PCV13对侵袭性和非侵袭性血清型的覆盖率分别为76.2%~95.2%和59.0%~98.8%, PPV23则分别为84.0%~98.3%和67.9%~99.1%。

四、疫苗1.疫苗研发进展:肺炎球菌疫苗是预防Spn感染的最有效手段。其使用历史最早可追溯到1911年Wright发明的全菌体疫苗, 预防大叶性肺炎。目前已上市的疫苗为肺炎球菌多糖疫苗(pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine, PPV)和肺炎球菌多糖结合疫苗(pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, PCV), 研发设计均基于Spn荚膜多糖, 涵盖了导致PD的最常见血清型。

(1) 多糖疫苗:早期4价的Spn荚膜多糖疫苗的保护效果已于1945年被证实[109], 但抗生素和化学药物的出现使已初步发展起来的多糖疫苗研发和应用停滞不前, 随后抗生素耐药菌株的出现使得疫苗研发再次被提上日程。1977年美国成功研制出14价肺炎球菌多糖疫苗(PPV14), 1978年由美国食品药品管理局(Food and Drug Administration)批准上市。1983年美国率先成功研制出PPV23并广泛使用, 覆盖的血清型包括1、2、3、4、5、6B、7F、8、9N、9V、10A、11A、12F、14、15B、17F、18C、19A、19F、20、22F、23F和33F型[110]。PPV为非T细胞依赖性抗原, 在<2岁婴幼儿体内难以产生有效的保护性抗体, 且不同人对不同血清型应答高低不一。目前在我国批准上市使用的PPV23有3种, 分别由默沙东(中国)有限公司、成都生物制品研究所有限责任公司和云南沃森生物技术股份有限公司生产。

(2) 多糖结合疫苗:PCV将Spn荚膜多糖与蛋白质共价结合, 从而荚膜多糖抗原由非T细胞依赖性抗原转变为T细胞依赖抗原, 使婴幼儿在免疫后能产生良好的抗体应答, 且能产生记忆应答。已批准上市的多糖结合疫苗有PCV7、PCV10和PCV13。

PCV7于2000年由惠氏(Wyeth)公司研发成功并经美国批准上市, 含4、6B、9V、14、18C、19F和23F型7个血清型[46], 目前已被PCV13替代。PCV10于2009年由葛兰素史克(GlaxoSmithKline)公司研制成功并经欧盟批准上市, 含1、4、5、6B、7F、9V、14、18C、19F和23F型10个血清型。PCV13于2010年由辉瑞公司(原惠氏公司)研制成功并经美国批准上市, 含1、3、4、5、6A、6B、7F、9V、14、18C、19A、19F和23F型13个血清型。目前我国批准上市使用的PCV仅一种, 为辉瑞公司生产的PCV13。

(3) 未来疫苗:PCV也存在着血清型选择、荚膜血清型转换、制备过程复杂、成本价格较高等问题, 研究者开始关注其他方向的研发。①结合疫苗:包括PCV15在内覆盖更多血清型的多糖结合疫苗[111]。②蛋白疫苗:用Spn蛋白作为潜在候选疫苗, 包括Spn溶血素、Spn表面蛋白A(PspA)、胆碱结合蛋白A(CbpA)等, 其中PsaA和Spn溶血素是目前首选的候选疫苗[112]。Spn表面的蛋白抗原没有血清型的局限, 并已证实有很好的免疫原性和有效的免疫保护力, 因此是肺炎球菌疫苗发展的方向之一。③联合疫苗:着眼于将Spn蛋白疫苗研究中的候选因子混合在一起, 增强保护效能, 将多种Spn蛋白质混合制成联合疫苗, 是一个新的研究方向[113-115]。但尚未有一种联合疫苗得到认可, 需要继续尝试找出更好的组合。④脱氧核糖核酸(DNA)疫苗:对于DNA疫苗的研究, 在动物中已得到开展。有结果表明[116], 动物研究中Spn DNA通过刺激B细胞产生抗体和诱导吞噬细胞而在宿主保护机制中发挥非特异性作用。⑤减毒活疫苗:减毒活疫苗也是肺炎球菌疫苗的一个热门方向[117]。

2.疫苗免疫原性:肺炎球菌疫苗的免疫原性是反映疫苗接种后产生保护作用的间接指标。常用的免疫原性评价指标有各血清型IgG抗体≥0.35 μg/ml的比例、各血清型IgG抗体几何平均浓度(geometric mean concentration, GMC)、各血清型OPA抗体≥1:8的比例、各血清型OPA抗体几何平均滴度(geometric mean titer, GMT)。IgG抗体≥0.35 μg/ml和OPA抗体≥1:8与预防IPD的保护力有很好的相关性, 但是预防Spn中耳炎、肺炎或鼻咽部定植的IgG抗体浓度和OPA抗体滴度尚无统一定论[118]。

儿童接种PCV基础免疫2剂次或3剂次后再加强1剂次后均能产生较好的免疫原性。只是基础免疫后IgG抗体≥0.35 μg/ml的比例和GMC前者略低于后者, 加强免疫后, PCV能够产生良好的回忆反应, 个别血清型免疫原性较弱; 免疫原性检测结果OPA方法略低于ELISA; 老年人接种PCV13诱导的免疫应答等于或优于PPV23。PPV23也可诱导出明显的免疫应答, 但是各型血清阳转率差异较大。PCV/PPV23程序较PPV23/PCV程序产生的OPA抗体应答高。

(1) PCV免疫原性:

● PCV7和PCV13“3+1”免疫程序:婴儿3剂次基础免疫和1剂次加强免疫的免疫程序, 即在6周龄时启动基础免疫, 每针间隔4~8周; 1~2岁接种加强剂次。①3剂次基础免疫免疫原性:PCV7基础免疫后, 各血清型IgG抗体≥0.35 μg/ml的比例≥87%、OPA抗体≥1:8的比例≥80%[119]。接种PCV7儿童对6A、19A型有交叉保护。但是19A型OPA抗体≥1:8的比例远低于IgG抗体≥0.35 μg/ml比例, 说明诱导产生的19A型抗体功能较弱, 与美国引入PCV7后未观察到疫苗对19A的保护力结果一致[99]。PCV13基础免疫后, 各血清型IgG抗体≥0.35 μg/ml的比例均≥82%, 仅一项研究显示6B型的IgG抗体≥0.35 μg/ml的比例为72.6%。各血清型OPA抗体≥1:8的比例均≥84%。②加强免疫免疫原性[119]:PCV7和PCV13加强免疫后7种共有血清型的IgG抗体GMC均高于基础免疫后, PCV13的额外6种血清型的5种亦高于基础免疫后, 部分研究显示仅3型未升高或增高倍数较低。加强免疫后PCV7和PCV13的7种共有血清型OPA抗体≥1:8比例均≥96.7%;其余6种血清型均≥97.8%。PCV7和PCV13加强免疫后7种共有血清型的OPA抗体≥1:8的比例均大于等于基础免疫后的比例, PCV13额外6种血清型OPA抗体≥1:8的比例除6A和3型外, 其余4种均高于基础免疫后的比例。

●PCV7和PCV13“2+1”免疫程序:婴儿2剂次基础免疫和1剂次加强免疫免疫原性, 即2剂次基础免疫在婴儿6周龄时开始, 间隔时间在低龄婴儿最好在8周以上, 在≥7月龄的婴儿中最好间隔4~8周或更长; 在9~15月龄时加强免疫1剂次。在“2+1”程序中, PCV13与PCV7均诱导出较强的免疫应答[119]。但是基础免疫后各血清型IgG抗体≥0.35 μg/ml的比例和GMC均略低于3剂次基础免疫, 尤其是6B和23F型血清型。“2+1”免疫程序也能诱导回忆反应。加强免疫后PCV7和PCV13的7种共有血清型OPA抗体≥1:8比例均≥93.4%;其余6种血清型均≥98.7%。“2+1”免疫程序中所有血清型的OPA抗体GMT高于基础免疫后。

●PCV13在较大年龄儿童中的免疫原性:既往未接种过肺炎球菌疫苗、无疫苗接种禁忌、无免疫功能低下且未患过Spn引起的相关疾病的健康儿童中, 24~72月龄接种1剂次PCV13, 12~24月龄接种2剂次PCV13, 或者7~12月龄接种2剂次PCV13且12~16月龄加强免疫1剂次; 三种免疫程序免疫后诱导的13种血清型IgG抗体≥0.35 μg/ml的比例均≥88%, 24~72月龄接种1剂次PCV13组大部分血清型IgG抗体GMC低于其他两组; 三种免疫程序诱导的13种血清型IgG抗体GMC均不低于既往报告的3剂次基础免疫获得的结果; 若与“3+1”免疫程序相比, 大部分血清型GMC较低[120]。

●既往接种过PCV7者接种PCV13免疫原性:既往接种过PCV7的15~23月龄儿童接种2剂次PCV13(间隔≥56 d)和24~60月龄儿童接种1剂次PCV13, 两组的7种共有血清型抗体≥0.35 μg/ml的比例均≥98.2%, 其余6种血清型抗体≥0.35 μg/ml的比例≥92%, 较大年龄儿童其余6种血清型抗体GMC高于基础免疫后, 原因可能为已有Spn鼻咽部定植[121]。

接种4剂次PCV13、接种4剂次PCV7、PCV7基础免疫+PCV13加强免疫三组进行比较, PCV7/PCV13组加强免疫后的额外6种血清型IgG GMC高于3剂次PCV13基础免疫后, 但除3型外, 其余5种血清型低于4剂次PCV13组加强免疫后。对7种共有血清型, 3组均诱导产生强免疫应答, PCV7组略高于其余2组, 加强免疫后PCV7/PCV13组除6B外均低于PCV7组, 除6B、18C、23F外其余4种血清型均低于PCV13组[122]。

既往接种2剂次PCV7者接种1剂次PCV13后可诱导产生13种血清型IgG抗体GMC增高; 该程序诱导产生的额外6种血清型抗体GMC与其他研究报告的3剂次PCV13的差异无统计学意义[123]。

总之, 1或2剂次PCV13能加强PCV7诱导的7种血清型IgG抗体应答, 能诱导出针对额外6种血清型合理的免疫应答, 但是PCV7/PCV13序贯程序加强免疫后诱导的针对额外6种血清型的IgG抗体GMC低于4剂次PCV13程序。

●PCV13在老年人中的免疫原性:美国和欧洲开展的研究表明, 老年人接种PCV13诱导的相应血清型免疫应答等效或优于PPV23。60~64岁之前未接种过肺炎球菌疫苗者中, 接种1剂次PCV13者诱导的两种疫苗共有的12种血清型OPA抗体GMT中, 3、5、14和19F血清型OPA抗体GMT与接种1剂次PPV23者的差异无统计学意义, 其余8种共有血清型的OPA抗体GMT高于接种1剂次PPV23者[124]。在既往接种过1剂次PPV23且已间隔至少5年的≥70岁者中, 接种1剂次PCV13诱导的3型和14型OPA抗体GMT, 与接种1剂次PPV23诱导的OPA抗体GMT的差异无统计学意义, 其余10种血清型OPA抗体GMT高于接种1剂次PPV23者[125]。

●PCV和PPV23序贯程序的免疫应答:PCV/PPV23序贯程序较PPV23/PCV序贯程序产生的OPA抗体应答高[125-128]。接种PPV23后1年接种PCV13, 与接种PCV13后1年接种PPV23相比, 前者的OPA抗体应答低于后者[128]。接种PCV7或PCV13后分别间隔2、6、12个月或3~4年再接种PPV23, 结果表明, PPV23接种后抗体水平高于PCV接种前基线, 且非劣效于PCV接种后的抗体水平[128-131]。

(2) PPV23免疫原性:在具有免疫能力的成年人中, 用PPV23进行免疫接种可以诱导血清型特异性抗荚膜抗体水平显著增高, 在老年人中也是如此[129-134]。PPV23能诱导出≥65岁人群12种疫苗血清型(1、3、4、5、6B、7F、9V、14、18C、19A、19F、23F)的功能性免疫应答。免疫后65~74岁组和≥75岁组的OPA抗体GMT均显著增高, 两组免疫后/免疫前抗体增长倍数和4倍增高比例的差异均无统计学意义[135]。老年人首次接种疫苗后4年以上复种疫苗, 其抗荚膜抗体水平明显升高[136-137]。

<2岁婴幼儿对大多数血清型的Spn荚膜多糖抗体应答很弱[138-140]; ≥2岁儿童一般在疫苗接种后产生明显的抗体水平升高[141-143]。我国一项在>2岁儿童中开展的PPV23免疫原性研究表明, PPV23可诱导出明显的免疫应答, 23种血清型抗体的2倍增长率在51.49%~97.01%之间, 8、9N、18C和33F型血清型增长率>90%[144]。

(3) 同时接种的免疫原性:PCV与含白喉、破伤风、百日咳(无细胞和全细胞疫苗)、乙型肝炎、脊髓灰质炎(灭活疫苗和口服减毒活疫苗)、b型流感嗜血杆菌、麻疹、流行性腮腺炎、风疹、水痘、C群脑膜炎球菌(结合疫苗)、轮状病毒等抗原成分的单价疫苗或联合疫苗同时接种, 其免疫原性不会发生明显改变[145-146]。

≥65岁人群同时接种PPV23与流感疫苗, 与单独接种相比, 两种疫苗的免疫原性均未受到影响[147]。

(4) 特殊人群的免疫原性:免疫抑制人群如骨髓或器官移植、血液肿瘤、慢性肝病、炎症性肠病、正在使用免疫抑制治疗、慢性肾或呼吸道疾病病例, 疫苗应答均会减弱[148-154]。骨髓移植病例的应答减弱可能长达4~10年。严重B细胞缺乏患者抗体应答功能受损致疫苗无应答。有基础疾病但无免疫抑制人群, 如无脾、实体肿瘤、用TNF-α抑制剂治疗、风湿病、糖尿病、SCD病例和年纪较大的健康老人中, 疫苗应答不会减弱[16, 155-158]。既往接种过PPV23的无脾儿童再接种PCV与再接种PPV23相比, 抗体应答会持续更长时间[156]。何杰金淋巴瘤病例联合使用两种疫苗也会改善免疫应答[159]。对器官移植患者两种疫苗联合使用不会改善疫苗应答[160]。

3.疫苗的效力或效果:PCV引入已显著降低疫苗接种人群的Spn相关疾病, 如IPD、CAP、AOM、鼻窦炎等的发生率及鼻咽部携带率, 非疫苗接种人群的上述疾病发生率也有所下降。PCV13与PCV7相比, 前者降低上述疾病发生率及鼻咽部携带率的效果更优。PPV23接种后, 可预防IPD的发生; 但其保护效力在老年人群, 随着年龄的增加而下降。

(1) PCV7:一项临床试验数据表明[161], 在全程免疫的婴儿中PCV7预防疫苗血清型引起的IPD的效力为97.4%(95%CI:82.7%~99.9%)。另一项综述结果表明[162], <2岁健康儿童中PCV7预防疫苗覆盖血清型IPD的效力为80%(95%CI:58%~90%); 预防全因IPD的效力为58%(95%CI:29%~75%); 预防符合WHO标准的胸部X线确诊CAP的效力为27%(95%CI:15%~36%); 预防临床诊断CAP的效力为6%(95%CI:2%~9%)。另一项随机对照试验研究了PCV7对AOM的预防效力[163], 结果表明, 疫苗预防实验室确诊的疫苗血清型AOM的效力为57%(95%CI:44%~67%); 预防全部Spn血清型引起AOM的效力为34%(95%CI:21%~45%); 预防全因急性AOM的效力是6%~7%。

婴儿接种PCV7能够减少未接种人群的IPD发生率。1998-2008年18~49、50~64和≥65岁人群的IPD发生率分别下降34%、14%和37%。美国CDC数据显示, 接种PCV7可使该血清型引起的疾病发生率下降90%~93%, 其中年轻人全因CAP住院率明显下降[164]。

(2) PCV13:

●预防IPD的效果:PCV13应用已显著降低婴幼儿(包括接种和未接种者)IPD发生率, PCV13降低IPD发生率的效果优于PCV7。

美国使用“3+1”免疫程序, 当65%的18月龄儿童完成免疫程序, 且63%的14~59月龄全程接种PCV7儿童补种1剂PCV13后, 与继续使用PCV7相比, IPD发生率下降了64%(95%CI:59%~68%)。由6种新血清型引起的IPD发生率下降了93%(95%CI:91%~94%)。成年人IPD发生率下降12%~32%。由6种新血清型引起的IPD发生率下降58%~72%, 以18~49岁成年人效果最好。PCV13免疫引入3年后约可预防1万例IPD儿童病例和2万例成年病例, 减少3 000例死亡, 其中97%是成年人[165]。

加拿大也使用“3+1”免疫程序。PCV13引入3年后, <5岁儿童IPD发生率由18/10万降至14.2/10万, 但≥5岁人群的IPD发生率(9.7/10万)未改变。PCV13血清型的构成比明显下降, 儿童由66%降至41%;≥5岁人群由54%降至43%[166]。

英国和威尔士使用“2(2、4月龄)+1”免疫程序, 疫苗接种率超过90%, 2013-2014年度与PCV13引入前相比, 全年龄组的IPD发生率下降32%, 发生率比(incidence rate ratio, IRR)为0.68(95%CI:0.64~0.72);PCV7血清型病例减少86%, 另6种血清型病例减少69%, 下降最多的年龄组为<2岁(89%)和2~4岁(91%); 未接种成年人中也有明显下降(64%~72%), 与PCV7引入前相比, IPD发生率下降56%(IRR=0.44, 95%CI:0.43~0.47)[167]。

丹麦使用“2(3、5月龄)+1(12月龄)”免疫程序, 接种率为79%~92%, 未开展补种。引入PCV13后与基线相比下降21%(IRR=0.79, 95%CI:0.76~0.83)。在<2岁儿童中下降最明显(71%, IRR=0.29, 95%CI:0.21~0.37)。50~64岁和≥65岁未接种人群中也观察到下降, 分别为19.5%(IRR=0.80, 95%CI:0.73~0.88)和19.6%(IRR=0.75, 95%CI:0.70~0.80)[168]。

以色列使用“2+1”(2、4、12月龄接种)程序, 接种率超过70%。与PCV引入前相比, 由13种血清型引起的IPD发生率下降95%(IRR=0.05, 95%CI:0.03~0.09)[169]。

●预防CAP的效果:PCV13的应用已显著降低<2岁接种儿童的CAP发生率。美国报道PCV13引入后CAP住院率明显下降, <2、2~4岁儿童和18~39岁成年人中分别下降21%、17%和12%[170]。

法国一项针对1月龄至15岁人群的研究表明, PCV13应用前后相比, CAP病例数量下降16%, 其中婴儿病例下降32%;CAP严重程度也降低, 并发胸腔积液的病例下降53%。由PCV13覆盖血清型引起的病例下降74%[171]。

乌干达2008年引入PCV7, 2010年引入PCV13, 常规免疫使用“2+1”免疫程序, 对2005-2009年出生儿童开展1剂次PCV13补充免疫。PCV7和PCV13接种已显著降低0~14岁的CAP发生率, 与PCV7接种时期相比, PCV13接种进一步降低了CAP发生率[172]。

尼加拉瓜2010年引入PCV13的“3+0”免疫程序(2、4、6月龄接种)。PCV13引入前后相比, 婴儿和1岁儿童全因CAP住院率的IRR值分别为0.67(95%CI:0.59~0.75)和0.74(95%CI:0.67~0.81), CAP急诊的IRR值分别为0.87(95%CI:0.75~1.01)和0.84(95%CI:0.74~0.95);2~4和5~14岁儿童CAP就诊次数很少, 提示有人群免疫力[173]。

●预防其他非侵袭性疾病效果:一项研究显示, 在接种PCV13的39例AOM患者中耳分离物中, 除16型(不包含在PCV13中)外均未发现Spn, 提示PCV13对AOM有保护作用[174]。美国在PCV13引入1年后的一项研究发现, 15例AOM患者的鼓膜穿刺液中仅1例检出Spn(为11型, 非PCV13血清型)[175]。另一项研究比较PCV7引入前后和PCV13引入后AOM发生情况, PCV7引入后与PCV引入前相比, PCV7和6A血清型引起的AOM下降73%, PCV13引入后PCV7和6A血清型引起的AOM进一步下降(23%), 由PCV13额外血清型引起的AOM下降85%[176]。PCV13血清型引起的AOM已接近消除, Kaplan等[175]收集的中耳分离物中, PCV13血清型的分离比例明显下降, 由2011年的50%降至2013年的29%。

一项对91例<18岁Spn分离阳性的慢性鼻窦炎患者鼻窦分离物的分析发现, PCV13引入后病原的流行病学发生改变, 67%的分离物为非PCV13血清型, 且PCV13引入后PCV13血清型减少31%[177]。

●降低Spn携带率的效果:多项研究表明, PCV13可显著降低疫苗血清型Spn携带。PCV13引入使PCV7血清型携带进一步下降, 效果优于PCV7引入后。

Cohen等[178]研究了AOM患者的Spn携带率。结果表明, 在接种PCV13的儿童中, 总Spn携带率和PCV13中非PCV7血清型携带率明显低于仅接种PCV7的儿童。在接种PCV13和PCV7儿童中, 总Spn携带率分别为53.9%和64.6%, PCV13中非PCV7血清型携带率分别为9.5%和20.7%。

2010年美国波士顿开展的一项<60月龄儿童Spn携带率监测发现, 与未接种者相比, PCV13接种者中PCV13血清型菌定植下降74%, 携带率下降>50%, 表明疫苗有显著的间接效果[179]。

2012-2013年在英国开展的一项研究表明, 与PCV7引入前相比, 在PCV7和PCV13引入后PCV7血清型携带明显下降; 而PCV7引入后, PCV13额外6种血清型携带率增加, 但在PCV13引入后明显下降(OR=0.05, 95%CI:0.01~0.37)[180]。

(3) PPV23:接种PPV23后预防IPD的效力随着接种对象年龄的增加而下降, <55岁人群中效力最高, ≥85岁人群效力最低; 随着时间的增长而下降(接种后<3年效果最好, >5年效果最差)[181]。见表 1。

PPV23预防非菌血症性肺炎球菌肺炎的效力和效果尚存在争议, 但在健康成年和老年人中, 不同研究结果显示其预防IPD的效果一致。观察性研究表明, PPV23预防有基础疾病的免疫功能正常老年和成年人IPD的效果约50%~80%[182]。但是在免疫功能低下人群和高龄人群中的效果尚未证实。近期一项纳入15个随机对照试验(RCT)和7个观察性研究的Meta分析表明, 基于10个RCT结果, PPV23预防IPD的效力和效果为74%(95%CI:56%~85%); 基于7个观察研究结果获得的PPV23预防IPD的效力和效果为52%(95%CI:39%~63%)[182]。另一项Meta分析(包括6个RCT试验)结果表明[183], PPV23预防Spn菌血症的效力为10%(95%CI:-77%~54%)。1剂次PPV23在成年人中预防肺炎的保护效果较弱[184-185]。

(4) 同时接种效果:瑞典一项同时接种肺炎球菌疫苗和流感疫苗的研究表明, 在≥65岁成年人中, 与未接种疫苗的人群相比, 接种流感疫苗和肺炎球菌疫苗人群IPD住院率下降68%, 住院时间下降40%, PD的住院率下降13%, 住院时间下降38%[186]。

(5) 特殊人群效果:马拉维HIV感染者中PCV7预防PCV7血清型IPD的效果估计为74%(95%CI:30%~90%), PPV23提供的保护有限[187]。美国一项观察性研究表明, 在≤10岁SCD的儿童中接种≥1剂次PCV7, 疫苗预防IPD的效果为81%(95%CI:19%~96%)[158]。

4.免疫持久性:婴幼儿接种PCV13后, 体内能产生持久的保护性抗体, 一般能持续2年以上。欧洲一项研究对在2、3、4和12月龄接种4剂PCV13的婴幼儿进行随访, 发现PCV13加强免疫1年后, 除3型外, 其他血清型抗体浓度均≥0.35 μg/ml, 加强免疫2年后, 除4型和3型外, 各血清型抗体浓度仍≥0.35 μg/ml; PCV13在早产儿中接种后1~2年内, 抗体浓度虽略低于正常婴幼儿, 但大部分血清型抗体浓度同样≥0.35 μg/ml。此外, 从其他PCV的使用经验及其免疫持久性资料来看, PCV13保护期有望持续更长时间。

PPV23可诱导抗体滴度升高, 但随着时间增长抗体滴度会下降。老年人中, 疫苗接种4~7年的抗体滴度降至疫苗接种前的基线水平, 但是抗体下降的临床意义尚不清楚。开展的两项疫苗接种后保护力持久性研究中, 一项发现疫苗接种后疫苗效果随着年龄的增长而下降, 随着时间的延长而下降。另一研究发现, 疫苗接种后>9年疫苗效果仍然相对稳定[155]。由于随着年龄的增加Spn感染的发生率也增高[188], PPV23需再次接种。再次接种不会诱导加强免疫应答, 诱导的应答与基础应答相似, 如1~2年复种疫苗应答低, 不良事件发生的可能性也增高。如果至少5年的间隔复种疫苗, 未发现低应答[189]。复种的疫苗间隔通常为5年, 但是在无脾患者和严重免疫抑制患者中复种疫苗的间隔应缩短。

5.疫苗安全性:根据临床试验、上市后观察和综述等文献回顾, PCV7、PCV13和PPV23疫苗的单独接种、与其他疫苗同时接种及复种的安全性良好, 常见反应为接种部位疼痛、接种部位红肿等, 常见的全身反应为发热, 症状轻微且具有自限性。上市后能观察到热性惊厥、川崎病等疾病报告, 但未确定其因果关联。

(1) 局部反应:

●PCV7和PCV13:Li等[190]在广西地区开展的纳入800名健康儿童的开放对照研究中, 观察了PCV7基础免疫及加强免疫的安全性和有效性。在基础免疫中, 不管是单独接种或与白喉-破伤风-无细胞百日咳联合疫苗(diphtheria, tetanus, acellular pertussis combined vaccine, DTaP)同时接种, PCV7都有良好的安全性, 接种后注射部位出现红斑和硬结/肿胀的受试者分别为<12%和<8%, 仅1%的受试者出现>2.5 cm的红斑和硬结/肿胀; 在加强免疫中, 接种后注射部位出现的红斑和硬结/肿胀的受试者均<3%, 所有报告的红斑和硬结/肿胀均<2.5 cm或未经测量; 1%左右的受试者出现了触痛[191]。我国另一项安全性临床试验中, 纳入72名PCV13受种者, 成年人中最常见的局部反应为接种部位疼痛(95.8%), 儿童组最常见为肢体活动受限(75%), 婴儿组中为接种部位红肿(25%), 均为轻度或中度; 婴幼儿局部反应持续时间为≤2.4 d, 成年人接种部位疼痛平均持续3.3 d, 接种部位红和肿平均持续9 d[192]。

美国一项上市后监测研究发现, PCV13和PCV7的疑似预防接种异常反应(adverse events following immunization, AEFI)中最常见的局部反应均为接种部位红斑(构成比分别为25.5%、15.2%), 其次为接种部位肿(构成比分别为19.4%、5.5%)和接种部位疼痛(构成比分别为9.8%、5.5%)[193]。另一项针对美国疫苗不良事件报告系统(Vaccine Adverse Events Reporting System, VAERS)数据中≥19岁成年人接种PCV13后的分析发现, 19~65岁成年人最常见的局部反应为接种部位红斑、接种部位疼痛; >65岁为接种部位红斑和接种部位肿[194]。以上两项研究结果类似。

意大利的一项在老年人(≥70岁)的PCV13观察性研究发现, 最常见的局部反应为接种部位疼痛(27.4%)[195]。

●PCV10:在埃塞俄比亚开展一项多中心纵向研究证实, 儿童接种2剂次包装无防腐剂的PCV10后发生接种部位脓肿的风险不高于接种百白破-乙型肝炎-流感嗜血杆菌联合疫苗(DPT-HepB-Hib)[196]。同期在肯尼亚开展的类似研究结果也证实PCV10未增加接种部位脓肿的风险[197]。

●PPV23:2001年杨耀等[198]在广西梧州市对成都生物制品研究所研制的PPV23进行Ⅰ、Ⅱ~Ⅲ期临床研究。在Ⅰ期临床观察中25例受种者中, 发现9例在接种后6~24 h内接种部位疼痛的局部反应; 在Ⅱ~Ⅲ期临床中, 接种组总疼痛率为30.8%, 红肿反应率为0.1%, 未见其他局部反应发生。2009-2010年张岷等[199]对我国18个省(自治区、直辖市)大面积使用PPV23的临床安全性进行观察, 样本量接近15万人, 0~7 d内局部反应分别包括接种部位发红、肿胀、硬结、疼痛、瘙痒和皮疹, 发生率均<1%。

利用美国VAERS系统中1999-2013年监测数据对PPV23上市后安全性进行评估, 非严重AEFI中PPV23接种后最常见的局部反应为接种部位红斑(28%)和接种部位疼痛(25%)[200]。美国利用疫苗安全数据链接(Vaccine Safety Data link, VSD)系统对PPV23第3剂次接种进行评估发现[201], 与第1剂次和第2剂次相比, 接种第3剂次并未增加接种部位反应(需要就医)的风险。另一项关于PPV23复种(间隔至少5年)的研究显示[202], 与首剂次接种相比, 复种PPV23后2 d内局部反应(≥10.2 cm)增多(RR=3.3, 95%CI:2.1~5.1)。这些反应在3 d内(中位数)恢复。

(2) 全身反应:

●PCV7和PCV13:在南京市开展的PCV13安全性临床试验中, 成年人常见全身反应为肌肉疼痛、疲劳、头痛和关节痛, 部分儿童出现睡眠紊乱(延长或缩短)、轻度发热(37.7~38.5 ℃), 仅发现1例支气管肺炎, 与疫苗接种无关[192]。在李荣成等[191]开展PCV7基础免疫和加强免疫的安全性和有效性研究中, 基础免疫最常见的全身反应为发热, <13%的受试者出现发热(≥38 ℃); 加强免疫中, 约10%的受试者出现了发热(>37.5%), 其余食欲降低、易激惹和睡眠中断等反应也有报告, 且加强免疫未出现严重不良事件(severe adverse event, SAE)。

2010-2014年中国AEFI监测数据显示[203-207], PCV7常见异常反应为过敏性皮疹和血管性水肿。美国的一项上市后监测研究发现, PCV13的AEFI中最常见的全身反应为发热(24.2%)、烦躁(10.3%)、呕吐(9.2%); PCV7则为发热(32.2%)、烦躁(11.1%)和荨麻疹(10.0%)[136]。另一项研究也提示发热为19~65岁成年人接种PCV13的最常见全身反应[194]。

意大利一项在≥70岁老年人的PCV13观察性研究提示, 接种后肌肉疼痛(13.6%)、疲劳(10.7%)和头痛(9.9%)最常见, 发热(2.2%)低于临床试验结果[195]。

●PPV23:杨耀等[198]开展的PPV23Ⅰ、Ⅱ~Ⅲ期临床研究显示, Ⅰ期临床观察中仅1例(4%)出现接种后48 h内一过性提问升高(达到37.5 ℃); Ⅱ~Ⅲ期临床中, 全身轻中度发热反应率为0.6%(24~48 h后消失), 未见其他全身性反应。张岷等[199]开展的样本量接近15万人PPV23 Ⅳ期临床安全性观察中, 0~7 d内出现全身反应发热、头疼、乏力/嗜睡、烦躁、恶心/呕吐、腹泻、过敏反应, 其中发热发生率为1.2%, 其余发生率均<0.3%。

PPV23在美国上市后AEFI中最常见的全身反应在儿童和成年人中均为发热; 在上市后24年的监测中, 通过不均衡分析, 也未发现任何安全性担忧[200]。

中国2010-2014年AEFI监测结果显示[203-207], PPV23常见异常反应为过敏性皮疹和血管性水肿。

(3) 罕见事件或安全性信号:一项针对6~23月龄儿童预防接种后热性惊厥风险的研究发现, 虽然疫苗接种后热性惊厥的绝对风险很小, 但是与其他疫苗相比, PCV7接种后热性惊厥风险增高(IRR=1.98, 95%CI:1.00~3.91);三价灭活流感疫苗单独接种的热性惊厥风险没有增高(IRR=0.46, 95%CI:0.21~1.20), 但与PCV7同时接种则风险升高(IRR=3.50, 95%CI:1.13~10.85)[208]。

美国对PCV13上市后成年人接种后AEFI进行监测[194], 发现1例过敏性休克、11例吉兰-巴雷综合征(Guillain-Barre syndrome, GBS)和14例死亡, 但经过评估, 均无法确认与疫苗接种存在因果关联, 而且通过数据挖掘分析, 也未发现PCV13接种后存在GBS的不均衡报告信号。

美国加州Kaiser Permanente开展的一项上市后大型观察性研究(样本量为162 305人)中[209], 在分析安全性中以既往流感嗜血杆菌疫苗(Hib)接种婴儿作为对照, 发现PCV7接种后出现川崎病住院风险增加。Center等[209]利用该大型研究数据, 调整了相关混杂因素后分析发现, PCV7接种者与对照组, 川崎病住院风险的差异无统计学意义(RR=1.67, 95%CI:0.93~3.00), 仅在亚裔人群中存在关联(RR=3.33, 95%CI:1.85~6.01)。

(4) 不同疫苗比较:Thompson等[210]对在婴幼儿中开展PCV13和PCV7进行Meta分析(纳入9个国家13项临床试验), 发现两疫苗在婴儿中局部反应发生率类似, 如疼痛(46.7%、44.8%)、肿胀(28.5%、26.9%)、红(36.4%、33.9%); 在学步儿童(11~15月龄)中, 疼痛在PCV7中高于PCV13(54.4%、48.8%, P=0.005)。两组全身反应中, 发热发生率类似, 且均多数症状较轻(<39 ℃); 食欲减退、烦躁和睡眠干扰的发生率也类似。未发现两组之间严重AEFI发生率存在显著性差异。

Trotta等[211]对2009-2011年在意大利4个地区常规儿童预防接种活动中进行PCV7和PCV13安全性比较发现, PCV13和PCV7与无细胞百白破-流感嗜血杆菌-乙型肝炎-灭活脊髓灰质炎联合疫苗(DTaP-Hib-HepB-IPV)同时接种, 估算AEFI的IRR值为1.08(95%CI:0.70~2.91), 说明两者间的差异无统计学意义; 单独接种PCV13或与DTaP-Hib-HepB-IPV同时接种, 在整体AEFI上, 同时接种出现保护作用(IRR=0.59, 95%CI:0.49~0.72), 虽然此保护性未发现神经系统事件和惊厥, 但两者间的差异也无统计学意义(神经系统事件:IRR=1.44, 95%CI:0.77~2.67;惊厥:IRR=1.46, 95%CI:0.50~4.25)。尽管如此, 还是发现常规使用PCV13接种后神经系统事件或惊厥的风险上升, 因此建议开展进一步调查。

Tseng等[212]利用美国VSD系统对PCV13接种后(纳入599 229剂次疫苗)安全性进行评估, 并与之前(2005-2009年或2007-2009年)接种PCV7进行比较, 未发现热性惊厥、荨麻疹、血管性水肿、哮喘、血小板减少症和急性过敏反应明显升高, 脑病风险升高, 但审阅临床资料后未确认。PCV13与PCV7相比, 接种后0~28 d发生的川崎病相对风险为1.94(95%CI:0.79~4.86), 虽然差异无统计学意义, 但研究者建议针对此信号需开展进一步研究。

Arana利用美国VAERS数据对上市后PCV13和PCV7的安全性进行比较, 认为两疫苗接种后安全性事件构成类似, 未发现任何安全性担忧[2]。

2011年澳大利亚采用PCV13取代PCV7, 一项上市后在婴儿中的安全性研究显示[213], PCV13与PCV7接种后, 整体AEFI报告发生率分别为228.1/10万剂次和163.2/10万剂次(IRR=1.4, P<0.001), 有7种临床症状(诊断)两种疫苗存在显著性差异, 其中腹泻、烦躁、呕吐、腹部疼痛、嗜睡、胃肠道反应以PCV13高于PCV7, 低张力地反应状态(HHE)则反之。PCV7接种后最常见的AEFI为皮疹(21.1/10万剂次)、腹泻(16.9/10万剂次)、全身过敏反应(15.3/10万剂次)和发热(14.8/10万剂次); PCV13接种后最常见的AEFI为发热(30.9/10万剂次)、腹泻(29.8/10万剂次)、烦躁(28.1/10万剂次)和呕吐(23/10万剂次)。对于严重AEFI, PCV13与PCV7之间的差异无统计学意义(PCV13:19.54/10万剂次, PCV7:25.28/10万剂次, IRR=0.77, P=0.25)。研究中有急性过敏反应、惊厥等病例报告, 但未评估与疫苗是否存在因果关联, 也未发现罕见或严重AEFI的安全性信号。

(5) 不同疫苗同时接种:PCV7与DTaP-HepB-IPV同时接种后的发热(≥38 ℃)发生风险略高于单独接种两种疫苗, 但其发生率较低[214]。Ghaffar[215]对PCV7安全性回顾研究认为, 在英国、德国、法国开展的DTaP-IPV-Hib和口服脊髓灰质炎减毒活疫苗(OPV)与PCV7同时接种均未发现安全性问题。PCV7在HIV感染儿童、低出生体重和早产婴儿、SCD儿童中安全性亦良好[214]。

(6) 特殊人群疫苗接种:在加拿大开展的一项儿童器官移植受体PCV7和PPV23接种安全性研究纳入31例心脏移植、18例肝脏移植、5例肺移植和27例肾移植患者, 发现常见AEFI为局部反应(PCV7:19%, PPV23:16%)和发热(PCV:3.8%, PPV:4.9%), 未发现任何严重AEFI[216]。

6.成本效果:接种肺炎球菌疫苗可通过降低脑膜炎、肺炎等相关疾病的治疗、护理、交通成本和间接误工成本, 避免潜在后遗症相关成本, 从而减少个人、家庭、医疗卫生系统和全社会PD相关经济负担。按照WHO推荐的成本效果评价标准, 增量成本效果比小于所在国家人均国内生产总值时认为干预措施非常具有成本效果, 介于人均国内生产总值的1~3倍时认为具有成本效果。

(1) PCV:截至目前, 全球已发表大量关于PCV的经济学评价研究, 多数研究显示儿童接种PCV具有较好的成本效果。2016年一项纳入22项中低收入国家研究的系统综述中有20项研究显示PCV儿童免疫程序具有成本效益。此外, 多项系统综述均显示PCV13和PCV10具有相对于PCV7更好的成本效益[217-218]。很多国家已将PCV被纳入儿童免疫规划。截至2017年3月, 全球194个国家和地区已有137个将PCV纳入免疫规划[219]。

我国研究预测, 如果将PCV7纳入儿童免疫规划, 10年内将可预防1 620万Spn相关疾病及70.9万死亡, 但其中1 080万病例和63.6万死亡是因疫苗的间接群体保护效应才得以避免[220]。2013-2016年我国开展9项PCV相关的经济学评价研究显示[94-95, 220-224], 3项研究的结论为节约成本, 1项为非常具有成本效果, 3项为具有成本效果, 2项为不具有成本效果。结论为不符合成本效益的2项研究, 其敏感性分析显示PCV成本效果对疫苗价格、疫苗群体保护效应和PD发病率等敏感。涉及PCV13的研究只有2项, 均为社会角度研究, 并采用了Markov模型。Maurer等[222]比较了将PCV7、PCV10和PCV13纳入中国儿童免疫规划的成本效果, 该研究尽可能采用了中国流行病学资料, 费用资料引自对上海地区样本医院的研究, PCV价格为146美元, 疫苗接种费用2美元。结果发现, 与不接种疫苗相比, PCV7、PCV10和PCV13均具有成本效果, 但PCV13的增量成本效果比最小, 其中PCV7的增量成本效果比为1.822 4万美元/质量调整生命年(quality adjusted life year, QALY), PCV10为1.666 4万美元/QALY, PCV13为1.146 4万美元/QALY。Mo等[223]则在假设疫苗接种率为20%, 比较了PCV7、PCV13和PPV23对<7岁儿童PD的影响和各疫苗的成本效果, 研究中采用台湾地区的发病率资料, 而费用资料来自上海地区样本医院, 各剂次PCV价格和接种费用合计561.324美元, PPV23价格和接种费合计为30.647美元。结果显示, PPV23可以减少12.1%的肺炎和18.8%的IPD; PCV7可以减少12.2%的肺炎、4.2%的中耳炎和28.8%的IPD; 而PCV13可以减少最多的疾病负担, 减少15.3%的肺炎、10.0%的中耳炎和31.3%的IPD。与不接种疫苗相比, PPV23具有成本效果, PCV7和PCV13不具有成本效果, PCV7和PCV13的增量成本效果比分别为104 094美元/QALY和29 460美元/QALY。PCV7达到节省成本、非常具有成本效果、具有成本效果和不具有成本效果的价格分别为<330.80、330.80~347.39、347.39~380.60和>380.60美元; PCV13达到相应成本效果的价格分别为<452.56、452.56~480.01、480.01~534.95和>534.95美元。若要达到节省成本, PCV7和PCV13价格需要分别降低41.1%和19.4%。在该研究中, PPV23是以假设为基础的唯一具有成本效果的疫苗。但需要注意的是, PPV23不能预防<2岁儿童中的肺炎链球菌性疾病, 而该年龄组儿童是<5岁儿童中肺炎链球菌性疾病的发病高峰。在儿童中, 相对于PPV23, PCV具有可以诱导免疫记忆、降低鼻咽部病原携带率、对侵袭性和非侵袭性疾病的疫苗效果均较好等很多优势。因此, 中国可将PPV23作为预防>2岁儿童肺炎链球菌性疾病的初步选择; 若PCV大幅降低价格或实现国产化, PCV将是预防儿童肺炎链球菌性疾病的最佳选择。

(2) PPV23:多项对全球研究的系统综述发现, 在成年人尤其是老年人和高危人群中接种PPV23, 对于预防侵袭性PD具备成本效益, 甚至可能节省成本[225-227]。截至目前, 我国有8项关于PPV23的经济学评价研究报告, 其中2项是模型分析[223, 228], 6项是基于RCT的分析[229-234], 涉及>60岁老年人及COPD、糖尿病和心脏病患者等高危人群; 7项研究结果显示节省费用(效益成本比为2.06~12)[223, 229-234]; 1项在上海市>60岁老年人中的模型研究结果为PPV23接种非常具有成本效果(增量成本效果比为1.669 9万美元/QALY)[228]。

五、WHO和美国免疫咨询委员会(Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, ACIP)接种建议1.WHO[1]:建议全球各国均应将PCV纳入本国的儿童免疫接种规划, 特别是那些儿童死亡率高(即<5岁儿童死亡率>50‰)的国家应将引进多抗原PCV作为国家免疫规划中的高优先项目。PCV10和PCV13在疫苗覆盖的血清型方面具有相当的安全性和效力。在选择PCV时, 应考虑疫苗血清型是否符合本地确定的目标人群流行的血清型、疫苗的供应和成本效果方面的问题。如果已选用上述PCV中的某一种疫苗开始基础免疫, 后续剂次最好也选择同一产品。目前尚未证实PCV10和PCV13是否可交替使用。但在现有条件不允许使用同一种疫苗完成免疫程序时, 则应使用另一种PCV产品完成后续剂次接种。

在婴儿接种PCV时, 采用3剂基础免疫程序(“3+0”程序); 或者, 也可采用替代性的2剂基础免疫加1剂加强免疫程序(“2+1”程序)。在选择“3+0”程序和“2+1”程序时, 各国应充分考虑各地的具体情况, 如PD的流行病学、可能的接种率和疫苗各剂次接种的时间安排。如采用3p+0方案, 在6周龄时即可启动基础免疫, 每针间隔4~8周, 接种时间可以是6、10和14周龄, 或2、4和6月龄, 具体可视方便免疫接种安排而定。如选用2p+1方案, 2剂基础免疫在婴儿6周龄时即开始; 间隔时间在低龄婴儿最好在8周以上, 在≥7月龄的婴儿中最好间隔4~8周或更长。在9~15月龄时应加强免疫1剂。

对于既往未接种过PCV或未完成接种程序的儿童, 一旦从IPD康复, 应根据WHO推荐的与年龄相适应的接种程序进行接种。HIV阳性婴儿和早产儿如在12月龄前已完成3剂次基础免疫, 可在满1岁后再加强免疫1剂次。如接种程序中断, 应及时补种, 但无须重复既往已接种的剂次。

“初始免疫接种”(catch-up)作为疫苗纳入免疫规划的一部分, 可加速提供群体保护, 进而充分发挥疫苗对疾病的保护和降低细菌携带的效果。在引进PCV10或PCV13时, 为提供最大程度的免疫保护, 可为12~24月龄尚未接种过肺炎球菌结合疫苗的儿童以及2~5岁肺炎球菌感染高风险的儿童接种2剂(至少间隔2个月)。

肺炎球菌结合疫苗可与婴儿免疫接种规划中的其他任何疫苗同时、不同部位接种。

一般认为, 肺炎球菌结合疫苗接种于所有目标人群以及免疫功能低下者是安全的。肺炎球菌结合疫苗尚未获准用于接种某些年龄组, 如育龄期妇女。理论上PCV10和PCV13在妊娠期接种不太可能发生危害, 但迄今尚未对这种安全性进行过评估。

需要在流行病学特点不同的地区开展进一步的研究, 探讨>50岁人群大规模接种肺炎球菌结合疫苗产生的影响, 以明确在这一人群中开展肺炎球菌结合疫苗免疫接种的相对优先性。然而, 鉴于在婴儿中常规接种PCV7后, 成年人中已观察到明确的群体保护效应, 应把工作重点放在引进婴儿期肺炎球菌结合疫苗并保持其高接种率。

资源有限的地区常存在许多竞争性的卫生保健优先任务。在这些地区, 现有证据不支持在老龄人群和高危人群中常规开展PPV23接种, 由于受益证据等级较低, 也不建议在HIV阳性成年人中常规开展PPV23接种。在没有常规开展高危人群PPV23接种的国家, 根据现有数据不足以推荐引进PPV23, 以降低流感相关疾病的发病率和死亡率。

(1) 接种PCV13建议:所有<2岁儿童常规接种PCV13, 婴儿基础免疫3剂次, 常规在2、4和6月龄接种。首剂可以于6周龄接种。第4剂加强免疫推荐在12~15月龄接种。对于12月龄内儿童接种, 各剂次间至少间隔4周; 12月龄以上儿童接种, 每剂至少间隔8周。

>65岁成年人既往未接种过PCV13或接种史不详, 应接种1剂次PCV13。对大多数有免疫功能的成年人应在接种1剂次PCV13后至少1年后接种1剂次多糖疫苗(PPV23)加强免疫。免疫缺陷、脑脊液渗漏和耳蜗植入者的成年人至少8周后加强免疫。

(2)≥65岁成年人接种PCV13和PPV23的建议:

●未接种肺炎球菌疫苗:既往没有接种过肺炎球菌疫苗或接种史不详的年龄≥65岁成年人应首先接种1剂次PCV13, 接种后间隔6~12个月接种1剂PPV23;两种疫苗不应同时接种, PCV13和PPV23之间接种间隔最少为8周。

●既往接种过PPV23:既往接种过≥1剂次PPV23的≥65岁成年人, 若尚未接种PCV13, 也应接种1剂次PCV13。PCV13与最近1次接种PPV23间隔应至少1年。对于明确需要再次接种PPV23的患者, 应在PCV13接种后6~12个月内以及最近1次接种PPV23至少5年后进行接种。

(3) 6~18岁的免疫功能不全儿童接种PCV13和PPV23的建议:

●未接种PPV23:没有接种过PCV13的6~18岁儿童且由于解剖或功能衰竭(包括SCD)、HIV感染、人工耳蜗植入、脑脊液漏或其他免疫功能障碍因素而处于IPD风险增加的条件下, 应先接种1剂次PCV13, 8周后接种1剂次PPV23。对解剖或功能性贫血(包括SCD)、HIV感染或其他免疫功能不全的儿童, 在接种第1剂次PPV23的5年以后进行PPV23复种。

●既往接种过PPV23:未接种过PCV13的6~18岁儿童, 由于解剖学或功能性衰竭, 包括SCD、HIV感染、脑脊液渗漏、人工耳蜗植入或其他免疫功能不全因素导致IPD风险增加; 以及既往接受过至少1剂次PPV23, 不管有无接种PCV7, 应在最近1次接种PPV23至少8周后接种1剂次PCV13。如果明确需要第2剂PPV23, 应在最后1次接种PPV23后≥5年。以上儿童在65岁以前不应该接受超过2剂次PPV23。

(4) 免疫功能低下的成年人患者接种PCV13和PPV23建议:具有特定免疫功能缺陷的成年人, 符合肺炎球菌疫苗接种条件的, 应在其下一个肺炎球菌疫苗接种机会期间接种PCV13。

●未接种肺炎球菌疫苗者:年龄≥19岁的具有免疫功能低下症状、功能性或解剖学贫血、脑脊液漏或耳蜗植入物以及既往尚未接种过PCV13或PPV23的成年人应先接种1剂次PCV13, 至少8周后接种1剂次PPV23。PPV23接种应符合目前高危人群PPV23的接种建议。对于具有功能或解剖学贫血和免疫受损条件的19~64岁的成年人, 第2剂PPV23建议在第1剂PPV23接种5年后。另外, 65岁以前因任何症状接种PPV23的患者应在65岁, 或者在接种上1剂次PPV23至少5年之后复种。

●既往接种过PPV23:年龄≥19岁存在免疫功能低下症状, 既往接种过≥1剂次PPV23的成年人, 应在接种最后1剂次PPV23至少1年后接种PCV13。对于需要额外接种PPV23的患者, 应在接种PCV13后8周内以及最近1次接种PPV23后至少5年接种。

(5) 具有医学指征人群接种PCV13和PPV23的建议:ACIP列出了6~64岁人群使用PCV13和PPV23医学指征的建议(表 2)[237]。

目前, 肺炎球菌疫苗在我国属于第二类疫苗, 接种单位应遵照《疫苗流通和预防接种管理条例》和《预防接种工作规范》的要求, 按照疫苗说明书规定和“知情同意、自愿自费”的原则, 科学告知家长或受种者后, 为受种者及时提供疫苗接种。

1.接种对象:

(1) PCV13:适用于6周龄~15月龄婴幼儿。

(2) PPV23:用于2岁以上感染Spn、患PD风险增加的人群, 尤其是以下重点人群但不局限于以下人群:①老年人群; ②患有慢性心血管疾病(包括充血性心力衰竭和心肌病)、慢性肺疾病(包括COPD和肺气肿)或糖尿病的个体; ③患酒精中毒、慢性肝脏疾病(包括肝硬化)及脑脊液漏的个体; ④功能性或解剖性无脾个体(包括SCD和脾切除); ⑤免疫功能受损人群(包括HIV感染者、白血病、淋巴瘤、何杰金病、多发性骨髓瘤、一般恶性肿瘤、慢性肾衰或肾病综合征患者)、进行免疫抑制性化疗(包括皮质激素类)的患者以及器官或骨髓移植患者。

2.接种程序:

(1) PCV13:推荐常规免疫接种程序为2、4、6月龄进行基础免疫, 12~15月龄加强免疫。基础免疫首剂最早可以在6周龄接种, 之后各剂间隔4~8周。

(2) PPV23:通常应种对象只接种1剂次。对需要复种的, 按照说明书要求进行接种, 复种间隔至少为5年。

3.接种途径及剂量:

(1) PCV13:使用前充分摇匀, 仅供肌肉注射。首选部位婴儿为大腿前外侧(股外侧肌), 幼儿为上臂三角肌。肌肉注射剂量为0.5 ml, 注意避免神经和血管集中或其附近部位注射疫苗。

(2) PPV23:上臂外侧三角肌皮下或肌内注射。每次注射0.5 ml。

4.接种禁忌和注意事项:禁忌证意味着不应该接种疫苗。注意事项意味着在某些情况下, 如果疫苗接种的获益超过风险, 则可以接种疫苗。以下情形适用于所有疫苗:①对疫苗中任何成分过敏是接种该疫苗的禁忌证; ②中度或重症的急性疾病, 无论是否发热, 接种疫苗应谨慎。

需说明的注意事项:①严禁静脉注射; ②血小板减少症、任何凝血障碍或接受抗凝血剂治疗者, 接种途径为肌肉注射时应非常谨慎(应在凝血因子替代或类似治疗后尽早接种, 接种时应用更小的针头, 接种后按压注射部位≥2 min, 不得揉搓); ③疫苗只能对本身所含Spn血清型具有预防保护作用, 不能预防疫苗以外的血清型别和其他微生物导致的侵袭性疾病、肺炎或中耳炎; ④疫苗不能保证所有受种者都不会罹患PD; ⑤正在进行免疫抑制治疗的患者或有免疫功能障碍的, 可能无法达到预期的血清抗体应答; ⑥不推荐2岁以下(不包括2岁)的婴幼儿使用PPV23;⑦在中国尚未进行PCV13与其他疫苗同时接种的临床试验, 国内暂不推荐本品与其他免疫规划疫苗或常规儿童疫苗同时接种; ⑧接种本品时, 应备有肾上腺素等药物, 以备偶有发生严重过敏反应时急救用。接受本品注射者在注射后应在现场观察至少30 min。

其他禁忌和慎用情况可参考相应企业的疫苗说明书。

七、非疫苗预防措施预防感染性疾病的一般措施可预防Spn相关疾病。相关研究显示, 非纯母乳喂养、营养缺乏以及室内空气污染等可能是儿童人群患该病的危险因素。因此出生头几个月鼓励纯母乳喂养、锌元素的补充等[243]。在生长发育阶段, 根据发育状况给予足够的营养, 及时合理地添加辅食。要积极防治佝偻病等营养性疾病, 因其与肺炎的发生及治疗效果均有较密切的关系。多到户外活动, 锻炼身体, 增强体质, 提高自身的免疫力, 增强对寒冷天气的适应能力。应保证居室内空气流通, 减少室内空气污染[244]。由于细菌常经由飞沫传播, 在家人或周围儿童患流感等呼吸道感染性疾病时, 要尽量减少接触, 避免交叉感染。入秋后天气渐渐转凉, 更应注意预防PD。在疾病流行期避免在人群较多的公共场所活动。鼓励戒烟, 合理使用抗生素, 积极治疗基础疾病, 预防和管理HIV感染。做好常规疫苗接种, 如麻疹、流感疫苗接种, 对预防Spn感染有积极意义。

镰刀细胞贫血症的婴幼儿服用青霉素V(125 mg, 每天2次)与服用安慰剂相比较, 前者可降低Spn菌血症的发病率达84%。因此, 推荐上述患儿在出生后4个月之前每天使用青霉素进行预防。功能或解剖性无脾儿童, 推荐口服青霉素G或V, 以预防PD。对多糖疫苗很可能没有反应的无脾儿童(例如2岁以下或接受大剂量化疗及降细胞疗法的人), 用抗生素预防Spn感染[42]。

八、后续有待研究的相关问题肺炎球菌疫苗的应用有效地预防了Spn相关疾病的发生, 尤其是PCV的应用, 对儿童PD的预防效果显著且一致, 其疫苗的安全性也进一步得到确认。但是, 在疫苗应用前后, 还有一些涉及Spn病原、疾病、疫苗和宿主的相关问题需要研究解决, 有些相关结果需要进一步确认。

1.病原学和血清学检测:人们对可以鉴别细菌种类的替代技术给予了相当大的关注, 希望这些技术能够克服在CAP患者中进行痰检测的局限性[245]。在Spn抗体检测方面, ELISA法已经得到广泛验证, 抗体浓度和疫苗有效性之间的关联性也得到证实; 对于OPA方法, 由于可以检测抗体功能活性, 更能反映疫苗接种后产生抗体的保护效果, 将OPA方法标准化并易于推广使用应成为未来研究的重点。

2.致病机制:Spn血清型有90多种, 但是有的血清型致病的程度不同, 有的血清型不致病, 其机制不清, 需要开展更多的研究。有报道与Spn荚膜多糖的化学组成和分子大小有关[246-247]; 不同的血清型Spn毒力随它们的荚膜激活补体的经典途径和旁路途径、沉积并降解补体成分、抵抗吞噬作用的能力而变化[248-249]。

3.致病起始年龄人群的差异:发展中国家患IPD儿童起始月龄大大早于发达国家。发展中国家2月龄以内的儿童经常会成为Spn的携带者(相反, 美国儿童在平均6月龄时才携带首个菌株)[250], 与发达国家相比, 发展中国家的儿童在6月龄前患IPD的比例相对较大[251-253], 而且3周龄以内的新生儿感染并不少见[252]。需要对导致发病年龄差异的原因和因素开展研究, 以便有针对性调整不同地区的PD疫苗免疫策略和防控措施。

4.致病菌血清型谱分布随年龄的变化:在全球大多数地区, 与年龄较大儿童和成年人相比, 导致幼儿疾病的Spn血清型谱较窄[254-255], 3个血清型导致了50%的幼儿IPD, 4~5个血清型导致了50%的大龄儿童和成年人IPD[254]。1型和5型导致了儿童大部分IPD[254, 256-258]; 据报告, 18C型也具有此种趋势[259]。

5.抗生素耐药随着年龄、种族和地理区域的变化:从全球来看, 挪威、瑞典等北欧各国Spn的抗生素耐药率始终较低。相反, 法国、西班牙、中国香港地区、新加坡和南非的抗生素耐药率很高[260]。在美国, 田纳西州等南部各州发现Spn耐药株的频度比其他地方高[261-262]。5岁以下儿童的耐药株发生率最高。

6.预防带菌的研究结果不一致:英国一项研究对2岁以上婴儿接种PCV7后的对照研究显示, 接种组和对照组的疫苗血清型带菌率(或各种Spn)无显著性差异。南非对接种3剂次PCV9的对照研究显示, 儿童在5.3岁时, PCV9不再降低鼻咽部疫苗血清型带菌率。有研究显示, HIV感染的儿童Spn定植率为71.6%, 高于HIV阴性者Spn定植率(50.9%)。多项研究显示, 接种疫苗后儿童带菌率显著下降[263]。因此, 预防带菌的效果需要更多的研究加以证实。

7.疫苗应用后非疫苗血清型成为优势菌株的潜力:从美国CDC的核心细菌主动监测系统(Active Bacterial Core surveillance, ABCs)项目来源的数据表明, 非PCV7疫苗血清型导致的5岁以内儿童IPD病例数在1998/1999年和2007年增加了128%[99]。接种能够降低社区儿童疫苗覆盖的血清型Spn带菌率[264-267]。替代疾病发生概率很可能部分取决于非疫苗血清型导致疾病的传播能力和致病能力。疫苗血清型疾病的减少同时伴随着非疫苗血清型导致疾病的增加, 因此需要对疫苗血清型和非疫苗血清型导致的疾病进行评估, 以确定疫苗的整体效应。

8.<2岁儿童是采用“3+1”还是“2+1”免疫程序:对足月婴儿和早产婴儿, 选择2和4月龄、3和5月龄、或4和6月龄时接种2剂PCV7进行基础免疫, 在11~12月龄加强1次剂接种(“2+1”程序)诱发的免疫应答和免疫记忆与标准的3剂次基础加1剂次加强程序(“3+1”程序)相仿[268-273]。因此, 有许多国家采用“2+1”程序, 而不是“3+1”程序。另外, WHO还提出了一种“2+1”程序的变化程序“3+0”, 即完成基础免疫后不进行加强免疫。

9.抗体持久性与发病的关系:年长成年人在接种首剂PPV后产生的抗荚膜抗体在疫苗接种次年即出现明显降低[133, 136, 274], 首次接种后4~7年下降到疫苗接种前水平[136, 275-278]。由于有关接种首剂PPV23后产生的临床保护时间方面的资料有限, 因此, 这种下降的临床意义尚不清楚。

10.理想的肺炎球菌疫苗:尽管PCV有很好的安全性记录, 而且其对侵袭性感染的有效性已经得到证实, 但仍然有几方面的限制性问题。其一, PCV只对表达疫苗所含有的多糖荚膜的Spn感染具有保护作用。当前临床使用和研发的疫苗配方涵盖了在儿童中流行的75%~90%菌株[17, 98, 254, 279-280]。这个数字在某些地区或用于其他年龄组时还较低。其二, 非疫苗血清型替代疾病的可能性会削弱疫苗血清型疾病的减少所观察到的总效益。第三, 结合疫苗生产的复杂性导致了只有非常少的公司能够生产此种疫苗, 从一定程度上提高了疫苗的价格。

11.结合蛋白与含有同类蛋白疫苗间的影响:抗白喉抗体的基线水平与对PCV7的免疫应答程度相关:成人中白喉抗体水平越高, 对结合疫苗的应答越强[281]。另外, PCV7或PCV13分别联合接种含C群的脑膜炎球菌多糖结合疫苗后, C群脑膜炎球菌的杀菌力抗体GMT在PCV13联合接种组低于PCV7联合接种组, 但抗体阳性率在两组之间差异无统计学意义[282]。

12.PPV23接种率的提高:达到PPV23的高接种率是更好发挥疫苗作用的前提, 不论是发达国家[235], 还是我国已将PPV23纳入省级增加国家免疫规划的地区, 与儿童国家免疫规划疫苗的接种率相比, 均处于较低水平, 如何提高儿童以外人群的疫苗接种率也是将来研究的一个方向。

13.我国PCV13适应症人群:目前我国批准的PCV13推荐使用的人群基础免疫在6月龄前完成, 加强免疫在12~15月龄完成; 而对于已超出月龄儿童的PCV13接种没有相应的规定[239]。但国外监测显示, 1岁和2岁是IPD最易高发的两个年龄段[46, 62]。WHO和其他国家均有6月龄至5岁儿童不同年龄段的接种程序。此外, PCV13已在国外成人应用, 也已取得非常好的效果。

14.我国PPV23上市后说明书涉及的问题:目前我国批准上市应用的PPV23既有国内企业生产, 也有国外企业生产, 其品种都相同, 即均含有相同的23种Spn血清型的荚膜多糖抗原。但是, 不同企业说明书的适应证、适应人群、禁忌证等不同, 给接种人员使用带来很大困扰[240-242]。应研究同品种疫苗说明书一致性的问题。

15.我国PD疾病负担:PD的流行特征和病原学血清型分布是制定疫苗免疫策略的关键因素[283]。由于PD还没有建立系统监测的方法, 疾病流行特征和病原学血清型分布只是一些不系统的研究, 其结果可能给免疫策略带来偏差。2008年WHO已把PD作为最优先的疫苗可预防疾病, 也建议各国将肺炎球菌疫苗作为优先纳入国家免疫规划的疫苗。因此, 我国建立PD监测系统, 开展疾病监测和相关研究非常必要。

16.我国肺炎球菌疫苗应用成本效益:美国常规使用PCV13的成本-效益研究结果表明, PCV13的实际成本效益好于预期, 原因是未接种儿童和成年人疾病发病率也有所下降[284]; 数学模型研究显示, PCV节约成本为7 800美元/生命年。其他国家也进行了相似的分析, 得出了相似的结果[285-286]。发展中国家PCV成本-效益的分析提示, 该疫苗可以大幅降低死亡率, 每剂价格在1~5美元时可以得到很高的成本-效益[287]。这些成本效益研究结果是疫苗纳入免疫规划的关键证据。我国应加强这些方面的研究, 尤其是疫苗投入的合理成本。

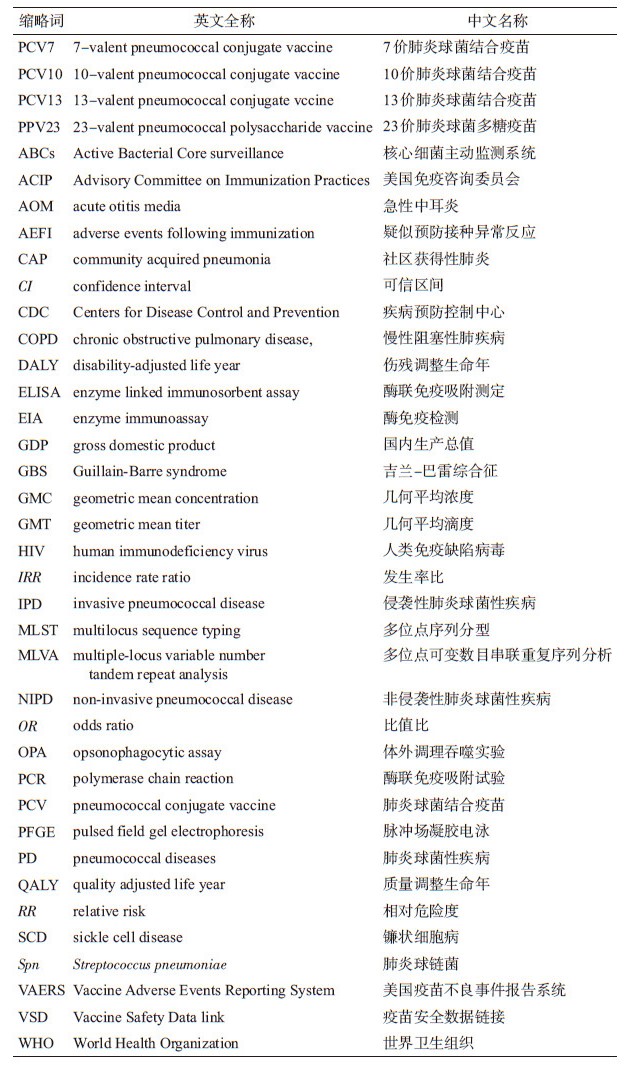

本文附常用术语中英文对照及缩略词表。

|

利益冲突: 无

| [1] | W HO. Pneumococcal vaccines:WHO position paper-2012[J]. Wkly Epidemiol Rec, 2012, 87(14): 129–144. |

| [2] | O'Brien KL, Wolfson LJ, Watt JP, et al. Burden of disease caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae in children younger than 5 years:global estimates[J]. Lancet, 2009, 374(9693): 893–902. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61204-6 |

| [3] | 中华人民共和国卫生部. 中国妇幼卫生事业发展报告(2011)[EB/OL]. (2011-09-21). http://www.gov.cn/gzdt/att/att/site1/20110921/001e3741a4740fe3bdab01.pdf. |

| [4] |

孙谨芳, 么鸿雁, 于石成, 等. 1990年和2010年中国3种细菌性脑膜炎疾病负担情况[J]. 疾病监测, 2015, 30(12): 1008–1013.

Sun JF, Yao HY, Yu SC, et al. Disease Burden of three kinds of bacterial meningitis in China, 1990 and 2010[J]. Dis Surveill, 2015, 30(12): 1008–1013. DOI:10.3784/j.issn.1003-9961.2015.12.006 |

| [5] |

黄广丽, 石庆生, 陈海霞, 等. 肺炎患儿咽部吸出物检测及细菌耐药性分析[J]. 河北医科大学学报, 2016, 37(1): 40–43.

Huang GL, Shi QS, Chen HX, et al. Bacteria detection in sputum and analysis of bacterial resistance in childhood pneumonia[J]. J Hebei Med Univ, 2016, 37(1): 40–43. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1007-3205.2016.01.011 |

| [6] |

刘又宁, 陈民钧, 赵铁梅, 等. 中国城市成人社区获得性肺炎665例病原学多中心调查[J]. 中华结核和呼吸杂志, 2006, 29(1): 3–8.

Liu YN, Chen MJ, Zhao TM, et al. A multicentre study on the pathogenic agents in 665 adult patients with community-acquired pneumonia in cities of China[J]. Chin J Tuberc Respir Dis, 2006, 29(1): 3–8. DOI:10.3760/j:issn:1001-0939.2006.01.003 |

| [7] | W HO. Meeting of the immunization strategic advisory group of experts, November 2007-conclusions and recommendations[J]. Wkly Epidemiol Rec, 2008, 83(1): 1–16. |

| [8] | Plotkin SA, Orenstein WA, Offit PA.Vaccines[M]. 6th ed. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2013: 542. |

| [9] | Park IH, Pritchard DG, Cartee R, et al. Discovery of a new capsular serotype(6C) within serogroup 6 of Streptococcus pneumoniae[J]. J Clin Microbiol, 2007, 45(4): 1225–1233. DOI:10.1128/JCM.02199-06 |

| [10] | Pennington JE. Treating respiratory infections in the era of cost control[J]. Am Fam Physician, 1986, 33(2): 153–160. |

| [11] | 张雪梅. 肺炎链球菌自然转化机制的研究进展[J]. 国外医学临床生物化学与检验学分册, 2002, 23(6): 348–350. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1673-4130.2002.06.016 |

| [12] |

孟江萍, 尹一兵. 肺炎链球菌致病机理的最新研究进展[J]. 微生物学杂志, 2002, 22(2): 39–41.

Meng JP, Yin YB. The newest advance in pathogenic mechanism of Streptococcus pneumoniae[J]. J Microbiol, 2002, 22(2): 39–41. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1005-7021.2002.02.015 |

| [13] | 陈保德. 肺炎链球菌致病的分子机理[J]. 国外医学临床生物化学与检验学分册, 2002, 23(6): 362–364. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1673-4130.2002.06.022 |

| [14] | 黄彬, 陈茶. 肺炎链球菌蛋白质类的毒力因子[J]. 国外医学临床生物化学与检验学分册, 1999, 20(2): 71–73. |

| [15] |

鲜墨, 吴忠道. 肺炎链球菌感染的流行病学及毒力因子研究进展[J]. 热带医学杂志, 2006, 6(6): 740–742, 693.

Xian M, Wu ZD. Epidemiological study of Streptococcus pneumoniae infection and the development of virulence factors[J]. J Trop Med, 2006, 6(6): 740–742, 693. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1672-3619.2006.06.045 |

| [16] | Meerveld-Eggink A, de Weerdt O, van Velzen-Blad H, et al. Response to conjugate pneumococcal and Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccines in asplenic patients[J]. Vaccine, 2011, 29(4): 675–680. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.11.034 |

| [17] | Hausdorff WP, Bryant J, Paradiso PR, et al. Which pneumococcal serogroups cause the most invasive disease:implications for conjugate vaccine formulation and use, part Ⅰ[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2000, 30(1): 100–121. DOI:10.1086/313608 |

| [18] | Romero-Steiner S, Libutti D, Pais LB, et al. Standardization of an opsonophagocytic assay for the measurement of functional antibody activity against Streptococcus pneumoniae using differentiated HL-60 cells[J]. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol, 1997, 4(4): 415–422. |

| [19] | Winkelstein JA, Smith MR, Shin HS. The role of C3 as an opsonin in the early stages of infection[J]. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med, 1975, 149(2): 397–401. DOI:10.3181/00379727-149-38815 |

| [20] | Romero-Steiner S, Frasch CE, Carlone G, et al. Use of opsonophagocytosis for serological evaluation of pneumococcal vaccines[J]. Clin Vaccine Immunol, 2006, 13(2): 165–169. DOI:10.1128/CVI.13.2.165-169.2006 |

| [21] | Taylor SN, Sanders CV. Unusual manifestations of invasive pneumococcal infection[J]. Am J Med, 1999, 107(1 Suppl 1): 12–27. DOI:10.1016/S0002-9343(99)00103-5 |

| [22] |

姚开虎, 赵顺英, 杨永弘. 儿童肺炎链球菌坏死性肺炎[J]. 中国循证儿科杂志, 2007, 2(6): 449–454.

Yao KH, Zhao SY, Yang YH. Streptococcus necrotizing pneumonia in children[J]. Chin J Evid-Based Pediatr, 2007, 2(6): 449–454. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1673-5501.2007.06.008 |

| [23] | 俞桑洁, 王辉, 沈叙庄, 等. 肺炎链球菌临床检验规程的共识[J]. 中华检验医学杂志, 2012, 35(12): 1066–1072. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1009-9158.2012.12.003 |

| [24] | 中华医学会儿科学分会呼吸学组, 《中华儿科杂志》编辑委员会. 儿童社区获得性肺炎管理指南(2013修订)(上)[J]. 中华儿科杂志, 2013, 51(10): 745–752. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0578-1310.2013.10.006 |

| [25] | Lyu S, Yao KH, Dong F, et al. Vaccine serotypes of Streptococcus pneumoniae with high-level antibiotic resistance isolated more frequently seven years after the licensure of PCV7 in Beijing[J]. Pediatr Infect Dis J, 2016, 35(3): 316–321. DOI:10.1097/INF.0000000000001000 |

| [26] | Song JH. Advances in pneumococcal antibiotic resistance[J]. Expert Rev Respir Med, 2013, 7(5): 491–498. DOI:10.1586/17476348.2013.816572 |

| [27] |

姚开虎, 王立波, 赵根明, 等. 四家儿童医院住院肺炎病例肺炎链球菌分离株的耐药性监测[J]. 中国当代儿科杂志, 2008, 10(3): 275–279.

Yao KH, Wang LB, Zhao GM, et al. Surveillance of antibiotic resistance of Streptococcus pneumoniae isolated from hospitalized patients with pneumonia in four children's hospitals in China[J]. Chin J Contemp Pediatr, 2008, 10(3): 275–279. |

| [28] |

王利民, 吴俊琪, 方寅飞. 学龄前儿童下呼吸道感染肺炎链球菌的流行病学特征与耐药性变迁[J]. 中国卫生检验杂志, 2016, 26(9): 1349–1352.

Wang LM, Wu JQ, Fang YF. Epidemiological characteristics and drug resistance changes of Streptococcus pneumoniae in lower respiratory tract infection of preschool children[J]. Chin J Health Lab Technol, 2016, 26(9): 1349–1352. |

| [29] |

王启, 张菲菲, 赵春江, 等. 2010-2011年中国肺炎链球菌耐药性和血清型研究[J]. 中华结核和呼吸杂志, 2013, 36(2): 106–112.

Wang Q, Zhang FF, Zhao CJ, et al. Antimicrobial resistance and serotype distribution of Streptococcus pneumoniae isolated from multicenters across China, 2010-2011[J]. Chin J Tuberc Respir Dis, 2013, 36(2): 106–112. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1001-0939.2013.02.009 |

| [30] | Kang LH, Liu MJ, Xu WC, et al. Molecular epidemiology of pneumococcal isolates from children in China[J]. Saudi Med J, 2016, 37(4): 403–413. DOI:10.15537/smj.2016.4.14507 |

| [31] | Yao KH, Wang LB, Zhao GM, et al. Pneumococcal serotype distribution and antimicrobial resistance in Chinese children hospitalized for pneumonia[J]. Vaccine, 2011, 29(12): 2296–2301. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.01.027 |

| [32] | Kim SH, Song JH, Chung DR, et al. Changing trends in antimicrobial resistance and serotypes of Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates in Asian countries:an Asian Network for Surveillance of Resistant Pathogens(ANSORP) study[J]. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2012, 56(3): 1418–1426. DOI:10.1128/AAC.05658-11 |

| [33] | W HO. Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine for childhood immunization-WHO position paper[J]. Wkly Epidemiol Rec, 2007, 82(12): 93–104. |

| [34] | Yao KH, Yang YH. Streptococcus pneumoniae diseases in Chinese children:past, present and future[J]. Vaccine, 2008, 26(35): 4425–4433. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.06.052 |

| [35] | Mahon BE, Ehrenstein V, Nørgaard M, et al. Perinatal risk factors for hospitalization for pneumococcal disease in childhood:a population-based cohort study[J]. Pediatrics, 2007, 119(4): e804–812. DOI:10.1542/peds.2006-2094 |

| [36] | Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. Preventing pneumococcal disease among infants and young children:recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices(ACIP)[J]. MMWR Recomm Rep, 2000, 49(RR-9): i–35. |

| [37] | Burgos J, Larrosa MN, Martinez A, et al. Impact of influenza season and environmental factors on the clinical presentation and outcome of invasive pneumococcal disease[J]. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis, 2015, 34(1): 177–186. DOI:10.1007/s10096-014-2221-9 |

| [38] | Pereiró I, Dez-Domingo J, Segarra L, et al. Risk factors for invasive disease among children in Spain[J]. J Infect, 2004, 48(4): 320–329. DOI:10.1016/j.jinf.2003.10.015 |

| [39] | Kadioglu A, Weiser JN, Paton JC, et al. The role of Streptococcus pneumoniae virulence factors in host respiratory colonization and disease[J]. Nat Rev Microbiol, 2008, 6(4): 288–301. DOI:10.1038/nrmicro1871 |

| [40] | Roy S, Knox K, Segal S, et al. MBL genotype and risk of invasive pneumococcal disease:a case-control study[J]. Lancet, 2002, 359(9317): 1569–1573. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08516-1 |

| [41] | Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A, et al. Infectious diseases society of America/American thoracic society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2007, 44(Suppl 2): S27–72. DOI:10.1086/511159 |

| [42] | C DC. Prevention of pneumococcal disease:recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices(ACIP)[J]. MMWR Recomm Rep, 1997, 46(RR-8): i–24. |

| [43] | CDC. Use of pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine for subjects over 65 years of age during an inter-pandemic period Stockholm, January 2007[EB/OL]. https://ecdc.europa.eu/sites/portal/files/media/en/publications/Publications/0701_TER_Use_of_pneumococcal_polysaccharide_vaccine.pdf. |

| [44] | Feikin DR, Feldman C, Schuchat A, et al. Global strategies to prevent bacterial pneumonia in adults with HIV disease[J]. Lancet Infect Dis, 2004, 4(7): 445–455. DOI:10.1016/S1473-3099(04)01060-6 |

| [45] | CDC. Recommended adult immunization schedule-United States, October 2006-September 2007[J/OL]. Wkly Epidemiol Rec, 2006, 55(40): Q1-Q4. [2006-10-13]. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5540a10.htm. |

| [46] | Robinson KA, Baughman W, Rothrock G, et al. Epidemiology of invasive Streptococcus pneumoniae infections in the United States, 1995-1998:opportunities for prevention in the conjugate vaccine era[J]. JAMA, 2001, 285(13): 1729–1735. DOI:10.1001/jama.285.13.1729 |

| [47] | Nuorti JP, Butler JC, Farley MM, et al. Cigarette smoking and invasive pneumococcal disease[J]. N Engl J Med, 2000, 342(10): 681–689. DOI:10.1056/NEJM200003093421002 |

| [48] | Bender JM, Ampofo K, Korgenski K, et al. Pneumococcal necrotizing pneumonia in Utah:does serotype matter?[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2008, 46(9): 1346–1352. DOI:10.1086/586747 |

| [49] | Talbot TR, Hartert TV, Mitchel E, et al. Asthma as a risk factor for invasive pneumococcal disease[J]. N Engl J Med, 2005, 352(20): 2082–2090. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa044113 |

| [50] | Sethi S, Murphy TF. Infection in the pathogenesis and course of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease[J]. N Engl J Med, 2008, 359(22): 2355–2365. DOI:10.1056/NEJMra0800353 |

| [51] | Talbot TR, Poehling KA, Hartert TV, et al. Seasonality of invasive pneumococcal disease:temporal relation to documented influenza and respiratory syncytial viral circulation[J]. Am J Med, 2005, 118(3): 285–291. DOI:10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.09.016 |

| [52] | Toschke AM, Arenz S, von Kries R, et al. No temporal association between influenza outbreaks and invasive pneumococcal infections[J]. Arch Dis Child, 2008, 93(3): 218–220. DOI:10.1136/adc.2006.098996 |

| [53] | Morens DM, Taubenberger JK, Fauci AS. Predominant role of bacterial pneumonia as a cause of death in pandemic influenza:implications for pandemic influenza preparedness[J]. J Infect Dis, 2008, 198(7): 962–970. DOI:10.1086/591708 |

| [54] | C DC. Vaccine preventable deaths and the Global Immunization Vision and Strategy, 2006-2015[J]. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 2006, 55(18): 511–515. |

| [55] | WHO. Estimated Hib and pneumococcal deaths for children under 5 years of age, 2008[R]. Geneva: WHO, 2013. |

| [56] | Walker CLF, Rudan I, Liu L, et al. Global burden of childhood pneumonia and diarrhoea[J]. Lancet, 2013, 381(9875): 1405–1416. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60222-6 |

| [57] | Naghavi M, Abajobir AA, Abbafati C, et al. Global, regional, and national age-sex specific mortality for 264 causes of death, 1980-2016:a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016[J]. Lancet, 2017, 390(10100): 1151–1210. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32152-9 |

| [58] | Isaacman DJ, McIntosh ED, Reinert RR. Burden of invasive pneumococcal disease and serotype distribution among Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates in young children in Europe:impact of the 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and considerations for future conjugate vaccines[J]. Int J Infect Dis, 2010, 14(3): e197–e209. DOI:10.1016/j.ijid.2009.05.010 |

| [59] | Karstaedt AS, Khoosal M, Crewe-Brown HH. Pneumococcal bacteremia during a decade in children in Soweto, South Africa[J]. Pediatr Infect Dis J, 2000, 19(5): 454–457. DOI:10.1097/00006454-200005000-00012 |

| [60] | Cutts FT, Zaman SMA, Enwere G, et al. Efficacy of nine-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine against pneumonia and invasive pneumococcal disease in The Gambia:randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial[J]. Lancet, 2005, 365(9465): 1139–1146. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71876-6 |

| [61] | Roca A, Sigaúque B, Quintó L, et al. Invasive pneumococcal disease in children < 5 years of age in rural Mozambique[J]. Trop Med Int Health, 2006, 11(9): 1422–1431. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-3156.2006.01697.x |

| [62] | Bjornson G, Scheifele D, Binder F, et al. Population-based incidence rate of invasive pneumococcal infection in children:Vancouver, 1994-1998[J]. Can Commun Dis Rep, 2000, 26(18): 149–151. |

| [63] | Eskola J, Takala AK, Kela E, et al. Epidemiology of invasive pneumococcal infections in children in Finland[J]. JAMA, 1992, 268(23): 3323–3327. DOI:10.1001/jama.1992.03490230053027 |

| [64] | von Kries R, Siedler A, Schmitt HJ, et al. Proportion of invasive pneumococcal infections in German children preventable by pneumococcal conjugate vaccines[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2000, 31(2): 482–487. DOI:10.1086/313984 |

| [65] | CDC. Epidemiology and prevention of vaccine-preventable diseases-pneumococcal disease[J/OL]. [2018-01-03]. http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/pneumo.htm. |

| [66] | Berezin EN, Iazzetti MA. Evaluation of the incidence of occult bacteremia among children with fever of unknown origin[J]. Braz J Infect Dis, 2006, 10(6): 396–399. DOI:10.1590/S1413-86702006000600007 |

| [67] | Avner JR, Baker MD. Occult bacteremia in the post-pneumococcal conjugate vaccine era:does the blood culture stop here?[J]. Acad Emerg Med, 2009, 16(3): 258–260. DOI:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00345.x |

| [68] | Alpern ER, Alessandrini EA, Bell LM, et al. Occult bacteremia from a pediatric emergency department:current prevalence, time to detection, and outcome[J]. Pediatrics, 2000, 106(3): 505–511. DOI:10.1542/peds.106.3.505 |

| [69] | WHO. DALY estimates, 2000-2015. Global summary estimates[J/OL]. http://www.who.int/entity/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/GHE2015_DALY_Global_2000_2015.xls?ua=1. |

| [70] | GBD 2015 DALYs, Collaborators HALE. Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life-years(DALYs) for 315 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy(HALE), 1990-2015:a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015[J]. Lancet, 2016, 388(10053): 1603–1658. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31460-X |

| [71] | Murray CJL, Vos T, Lozano R, et al. Disability-adjusted life years(DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990-2010:a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010[J]. Lancet, 2012, 380(9859): 2197–2223. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61689-4 |

| [72] | Weycker D, Strutton D, Edelsberg J, et al. Clinical and economic burden of pneumococcal disease in older US adults[J]. Vaccine, 2010, 28(31): 4955–4960. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.05.030 |

| [73] | Petit G, de Wals P, Law B, et al. Epidemiological and economic burden of pneumococcal disease in Canadian children[J]. Can J Infect Dis, 2003, 14(4): 215–220. DOI:10.1155/2003/781794 |

| [74] | 国家卫生和计划生育委员会. 2015中国卫生和计划生育统计年鉴[M]. 北京: 中国协和医科大学出版社, 2015. |

| [75] |

宁桂军, 王旭霞, 刘世文, 等. 2015-2016年甘肃省白银市5岁以下儿童社区获得性肺炎疾病负担回顾性调查[J]. 中国疫苗和免疫, 2017, 23(1): 18–21, 12.

Ning GJ, Wang XX, Liu SW, et al. Retrospective investigation of the disease burden of community acquired pneumonia among children under 5 years old in Baiyin city of Gansu province, 2015-2016[J]. Chin J Vaccines Immuniz, 2017, 23(1): 18–21, 12. |

| [76] | Ning GJ, Wang XX, Wu D, et al. The etiology of community-acquired pneumonia among children under 5 years of age in mainland China, 2001-2015:a systematic review[J]. Hum Vaccin Immunother, 2017, 13(11): 2742–2750. DOI:10.1080/21645515.2017.1371381 |

| [77] | Tao LL, Hu BJ, He LX, et al. Etiology and antimicrobial resistance of community-acquired pneumonia in adult patients in China[J]. Chin Med J(Engl), 2012, 125(17): 2967–2972. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0366-6999.2012.17.002 |

| [78] | Huang HH, Zhang YY, Xiu QY, et al. Community-acquired pneumonia in Shanghai, China:microbial etiology and implications for empirical therapy in a prospective study of 389 patients[J]. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis, 2006, 25(6): 369–374. DOI:10.1007/s10096-006-0146-7 |

| [79] | Zhou MG, Wang HD, Zhu J, et al. Cause-specific mortality for 240 causes in China during 1990-2013:a systematic subnational analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013[J]. Lancet, 2016, 387(10015): 251–272. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00551-6 |

| [80] | Limcangco MRT, Salole EG, Armour CL. Epidemiology of Haemophilus influenzae type b meningitis in Manila, Philippines, 1994 to 1996[J]. Pediatr Infect Dis J, 2000, 19(1): 7–11. DOI:10.1097/00006454-200001000-00003 |

| [81] | Mahmoud R, Mahmoud M, Badrinath P, et al. Pattern of meningitis in Al-Ain medical district, United Arab Emirates-a decadal experience(1990-99)[J]. J Infect, 2002, 44(1): 22–25. DOI:10.1053/jinf.2001.0937 |

| [82] | Hussain IHM, Sofiah A, Ong LC, et al. Haemophilus influenzae meningitis in Malaysia[J]. Pediatr Infect Dis J, 1998, 17(9 Suppl): S189–190. |

| [83] | Taylor HG, Michaels RH, Mazur PM, et al. Intellectual, neuropsychological, and achievement outcomes in children six to eight years after recovery from Haemophilus influenzae meningitis[J]. Pediatrics, 1984, 74(2): 198–205. |

| [84] | 卫生福利部统计处. 全民健康保险医疗统计[EB/OL]. (2017). http://www.mohw.gov.tw/CHT/DOS/Statistic.aspx?f_list_no=312&fod_list_no=1604. |

| [85] | 卫生福利部统计处. 死因统计[EB/OL]. (2017). http://www.mohw.gov.tw/CHT/DOS/Statistic.aspx?f_list_no=312&fod_list_no=1610. |

| [86] | Ting YT, Lu CY, Shao PL, et al. Epidemiology of community-acquired bacteremia among infants in a medical center in Taiwan, 2002-2011[J]. J Microbiol Immunol Infect, 2015, 48(4): 413–418. DOI:10.1016/j.jmii.2013.10.005 |

| [87] | 王进东, 张再兴, 孙静涛, 等. 唐山地区2008-2013年儿童急性中耳炎流行病学调查[J]. 中国妇幼保健, 2015, 30(6): 939–941. DOI:10.7620/zgfybj.j.issn.1001-4411.2015.06.47 |

| [88] |

刘俊英, 赵英, 张爱凤, 等. 唐山地区儿童急性中耳炎常见病原菌及药物敏感性分析[J]. 现代预防医学, 2014, 41(19): 3517–3519, 3529.

Liu JY, Zhao Y, Zhang AF, et al. Analysis of the common pathogens of acute otitis media and their drug sensitivity in children in Tangshan[J]. Mod Prevent Med, 2014, 41(19): 3517–3519, 3529. |

| [89] |

景阳, 韩想利, 王宇娟, 等. 西安地区290例儿童急性中耳炎分泌物细菌培养及药敏分析[J]. 检验医学与临床, 2016, 13(4): 457–459.

Jing Y, Han XL, Wang YJ, et al. Analysis of the 260 common pathogens of a cute otitis media and their drug sensitivity in children in Xi'an[J]. Labor Med Clin, 2016, 13(4): 457–459. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1672-9455.2016.04.009 |

| [90] | Evaluation IfHMa. Global health data exchange[EB/OL]. http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool. |

| [91] | Li Y, An ZJ, Yin DP, et al. Disease burden of community acquired pneumonia among children under 5 y old in China:A population based survey[J]. Hum Vaccin Immunother, 2017, 13(7): 1681–1687. DOI:10.1080/21645515.2017.1304335 |

| [92] | 周勇, 陈泽玲, 王缃赟. 珠海市社区获得性肺炎疾病负担研究[J]. 深圳中西医结合杂志, 2016, 26(20): 81–82. DOI:10.16458/j.cnki.1007-0893.2016.20.040 |

| [93] |

邸明芝, 曹迎, 黄辉, 等. 248例成人社区获得性肺炎病例疾病负担调查[J]. 现代预防医学, 2014, 41(14): 2560–2562, 2584.

Di MZ, Cao Y, Huang H, et al. Investigation on the expenses of 248 adult patients with community-acquired pneumonia in Dongcheng District, Beijing[J]. Mod Prevent Med, 2014, 41(14): 2560–2562, 2584. |

| [94] |

宋圣帆. 肺炎链球菌疾病费用研究与七价肺炎球菌结合疫苗的卫生经济学评价[D]. 上海: 复旦大学, 2013.

Song SF. The study on burden of pneumococcal diseases and cost effectiveness analysis of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in China[D]. Shanghai: Fudan University, 2013. |

| [95] |

朱琳, 刘国恩, 李冬美, 等. 儿童七价肺炎球菌结合疫苗的成本效果分析[J]. 中国卫生经济, 2013, 32(4): 71–75.

Zhu L, Liu GN, Li DM, et al. Ecomomic evaluation of 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine(PCV7)[J]. Chin Health Econom, 2013, 32(4): 71–75. DOI:10.7664/CHE20130423 |

| [96] | 刘文婷. 部分地区三种主要细菌性脑膜炎病例经济负担调查[D]. 北京: 中国疾病预防控制中心, 2016. |

| [97] | Wu DBC, Roberts CS, Huang YC, et al. A retrospective study to assess the epidemiological and economic burden of pneumococcal diseases in adults aged 50 years and older in Taiwan[J]. J Med Econ, 2014, 17(5): 312–319. DOI:10.3111/13696998.2014.898644 |

| [98] | Johnson HL, Deloria-Knoll M, Levine OS, et al. Systematic evaluation of serotypes causing invasive pneumococcal disease among children under five:the pneumococcal global serotype project[J]. PLoS Med, 2010, 7(10): e1000348. DOI:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000348 |

| [99] | Pilishvili T, Lexau C, Farley MM, et al. Sustained reductions in invasive pneumococcal disease in the era of conjugate vaccine[J]. J Infect Dis, 2010, 201(1): 32–41. DOI:10.1086/648593 |

| [100] | Kaplan SL, Barson WJ, Lin PL, et al. Serotype 19A is the most common serotype causing invasive pneumococcal infections in children[J]. Pediatrics, 2010, 125(3): 429–436. DOI:10.1542/peds.2008-1702 |

| [101] | Kaplan SL, Barson WJ, Lin PL, et al. Early trends for invasive pneumococcal infections in children after the introduction of the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine[J]. Pediatr Infect Dis J, 2013, 32(3): 203–207. DOI:10.1097/INF.0b013e318275614b |

| [102] | Iroh Tam PY, Thielen BK, Obaro SK, et al. Childhood pneumococcal disease in Africa-a systematic review and meta-analysis of incidence, serotype distribution, and antimicrobial susceptibility[J]. Vaccine, 2017, 35(15): 1817–1827. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.02.045 |

| [103] | Foster D, Knox K, Walker AS, et al. Invasive pneumococcal disease:epidemiology in children and adults prior to implementation of the conjugate vaccine in the Oxfordshire region, England[J]. J Med Microbiol, 2008, 57(Pt 4): 480–487. DOI:10.1099/jmm.0.47690-0 |

| [104] | Motlova J, Benes C, Kriz P. Incidence of invasive pneumococcal disease in the Czech Republic and serotype coverage by vaccines, 1997-2006[J]. Epidemiol Infect, 2009, 137(4): 562–569. DOI:10.1017/S0950268808001301 |

| [105] | Chen Y, Deng W, Wang SM, et al. Burden of pneumonia and meningitis caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae in China among children under 5 years of age:a systematic literature review[J]. PLoS One, 2011, 6(11): e27333. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0027333 |

| [106] |

韦宁, 安志杰, 王华庆. 中国≤18岁人群肺炎球菌相关病例中肺炎球菌血清型分布的系统评价[J]. 中国疫苗和免疫, 2014, 20(6): 547–555.

Wei N, An ZJ, Wang HQ. A systematic review of the serotype distribution of Streptococcus pneumoniae(pneumococcus)among all cases under 18 Years Old of pneumococcal infection in China[J]. Chin J Vaccines Immun, 2014, 20(6): 547–555. |

| [107] | 傅锦坚, 丁燕玲, 徐少林, 等. 中国内地健康儿童鼻咽携带肺炎链球菌及其血清型分布的系统评价[C]//第七届中国临床微生物学大会暨微生物学与免疫学论坛论文汇编. 宁波: 中国微生物学会临床微生物学专业委员会, 医学参考报社, 宁波大学, 宁波大学医学院附属医院, 2016. |

| [108] | Lyu S, Hu HL, Yang YH, et al. A systematic review about Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype distribution in children in mainland of China before the PCV13 was licensed[J]. Expert Rev Vaccines, 2017, 16(10): 997–1006. DOI:10.1080/14760584.2017.1360771 |

| [109] | MacLeod CM, Hodges RG, Heidelberger M, et al. Prevention of pneumococcal pneumonia by immunization with specific capsular polysaccharides[J]. J Exp Med, 1945, 82(6): 445–465. DOI:10.1084/jem.82.6.445 |

| [110] | Nieminen T, K?yhty H, Virolainen A, et al. Circulating antibody secreting cell response to parenteral pneumococcal vaccines as an indicator of a salivary IgA antibody response[J]. Vaccine, 1998, 16(2/3): 313–319. DOI:10.1016/S0264-410X(97)00162-X |

| [111] | Skinner JM, Indrawati L, Cannon J, et al. Pre-clinical evaluation of a 15-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine(PCV15-CRM197) in an infant-rhesus monkey immunogenicity model[J]. Vaccine, 2011, 29(48): 8870–8876. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.09.078 |

| [112] | 林铃. 肺炎球菌疫苗新策略[J]. 国际生物制品学杂志, 2006, 29(1): 5–7. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1673-4211.2006.01.003 |

| [113] | Briles DE, Ades E, Paton JC, et al. Intranasal immunization of mice with a mixture of the pneumococcal proteins PsaA and PspA is highly protective against nasopharyngeal carriage of Streptococcus pneumoniae[J]. Infect Immun, 2000, 68(2): 796–800. DOI:10.1128/IAI.68.2.796-800.2000 |

| [114] | Briles DE, Hollingshead S, Brooks-Walter A, et al. The potential to use PspA and other pneumococcal proteins to elicit protection against pneumococcal infection[J]. Vaccine, 2000, 18(16): 1707–1711. DOI:10.1016/S0264-410X(99)00511-3 |

| [115] | Cao J, Chen DP, Xu WC, et al. Enhanced protection against pneumococcal infection elicited by immunization with the combination of PspA, PspC, and ClpP[J]. Vaccine, 2007, 25(27): 4996–5005. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.04.069 |

| [116] | Lee LH, Lee CJ, Frasch CE. Development and evaluation of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines:clinical trials and control tests[J]. Crit Rev Microbiol, 2002, 28(1): 27–41. DOI:10.1080/1040-840291046678 |

| [117] |

王一平. 转化缺失的无荚膜肺炎链球菌作为活疫苗候选菌株的安全性及保护效果评价研究[D]. 重庆: 重庆医科大学, 2013.

Wang YP. The experimental research on safty and protective efficacy of a series of transformation defected noncapsulated Streptococcus pneumoniae strains as attenuated live vaccine candidates[D]. Chongqing: Chongqing Medical University, 2013. http://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTotal-SWZP201608017.htm |

| [118] | Jódar L, Butler J, Carlone G, et al. Serological criteria for evaluation and licensure of new pneumococcal conjugate vaccine formulations for use in infants[J]. Vaccine, 2003, 21(23): 3265–3272. DOI:10.1016/S0264-410X(03)00230-5 |

| [119] | Nunes MC, Madhi SA. Review on the immunogenicity and safety of PCV-13 in infants and toddlers[J]. Expert Rev Vaccines, 2011, 10(7): 951–980. DOI:10.1586/erv.11.76 |

| [120] | Wysocki J, Brzostek J, Szymański H, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of a 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine administered to older infants and children naive to pneumococcal vaccination[J]. Vaccine, 2015, 33(14): 1719–1725. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.02.005 |

| [121] | Frenck RJr, Thompson A, Yeh SH, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in children previously immunized with 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine[J]. Pediatr Infect Dis J, 2011, 30(12): 1086–1091. DOI:10.1097/INF.0b013e3182372c6a |

| [122] | EG, F L, S B. Safety and immunogenicity of a 13-valentpneumococcal conjugate vaccine given with routine pediatric vaccination to healthy children in France[C]//Proceedings of the 27th Annual Meeting of the European Societyfor Paediatric Infectious Disease(ESPID). Brussels, Belgium: ESPID, 2009. |

| [123] | SA S, SP T, G S. Phase 3, open-label trial of 13-valentpneumococcal conjugate vaccine as a toddler dose in healthy children previously partially immunized with 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine[C]//Proceedings of the 28th Annual Meeting of the EuropeanSociety for Paediatric Infectious Diseases(ESPID). Nice, France: ESPID, 2010. |

| [124] | Jackson LA, Gurtman A, van Cleeff M, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of a 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine compared to a 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine in pneumococcal vaccine-naive adults[J]. Vaccine, 2013, 31(35): 3577–3584. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.04.085 |

| [125] | Greenberg RN, Gurtman A, Frenck RW, et al. Sequential administration of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine in pneumococcal vaccine-naïve adults 60-64 years of age[J]. Vaccine, 2014, 32(20): 2364–2374. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.02.002 |

| [126] | Jackson LA, Gurtman A, van Cleeff M, et al. Influence of initial vaccination with 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine or 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine on anti-pneumococcal responses following subsequent pneumococcal vaccination in adults 50 years and older[J]. Vaccine, 2013, 31(35): 3594–3602. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.04.084 |

| [127] | Goldblatt D, Southern J, Andrews N, et al. The immunogenicity of 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine versus 23-valent polysaccharide vaccine in adults aged 50-80 years[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2009, 49(9): 1318–1325. DOI:10.1086/606046 |

| [128] | Miernyk KM, Butler JC, Bulkow LR, et al. Immunogenicity and reactogenicity of pneumococcal polysaccharide and conjugate vaccines in alaska native adults 55-70 years of age[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2009, 49(2): 241–248. DOI:10.1086/599824 |

| [129] | Kolibab K, Smithson SL, Shriner AK, et al. Immune response to pneumococcal polysaccharides 4 and 14 in elderly and young adults[J]. Immun Ageing, 2005, 2: 10. DOI:10.1186/1742-4933-2-10 |

| [130] | Carson PJ, Nichol KL, O'Brien J, et al. Immune function and vaccine responses in healthy advanced elderly patients[J]. Arch Intern Med, 2000, 160(13): 2017–2024. DOI:10.1001/archinte.160.13.2017 |

| [131] | Romero-Steiner S, Musher DM, Cetron MS, et al. Reduction in functional antibody activity against Streptococcus pneumoniae in vaccinated elderly individuals highly correlates with decreased IgG antibody avidity[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 1999, 29(2): 281–288. DOI:10.1086/520200 |

| [132] | Artz AS, Ershler WB, Longo DL. Pneumococcal vaccination and revaccination of older adults[J]. Clin Microbiol Rev, 2003, 16(2): 308–318. DOI:10.1128/CMR.16.2.308-318.2003 |

| [133] | Brandão AP, de Oliveira TC, de Cunto Brandileone MC, et al. Persistence of antibody response to pneumococcal capsular polysaccharides in vaccinated long term-care residents in Brazil[J]. Vaccine, 2004, 23(6): 762–768. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.07.024 |

| [134] | Simonsen V, Brandão AP, Brandileone MCC, et al. Immunogenicity of a 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine in Brazilian elderly[J]. Braz J Med Biol Res, 2005, 38(2): 251–260. DOI:10.1590/S0100-879X2005000200014 |

| [135] | Ahn JG, Kim HW, Choi HJ, et al. Functional immune responses to twelve serotypes after immunization with a 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine in older adults[J]. Vaccine, 2015, 33(38): 4770–4775. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.08.002 |

| [136] | Törling J, Hedlund J, Konradsen HB, et al. Revaccination with the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine in middle-aged and elderly persons previously treated for pneumonia[J]. Vaccine, 2003, 22(1): 96–103. DOI:10.1016/S0264-410X(03)00521-8 |

| [137] | Lackner TE, Hamilton RG, Hill JJ, et al. Pneumococcal polysaccharide revaccination:immunoglobulin g seroconversion, persistence, and safety in frail, chronically ill older subjects[J]. J Am Geriatr Soc, 2003, 51(2): 240–245. DOI:10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51064.x |

| [138] | Koskela M, Leinonen M, Haiva VM, et al. First and second dose antibody responses to pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine in infants[J]. Pediatr Infect Dis, 1986, 5(1): 45–50. DOI:10.1097/00006454-198601000-00009 |

| [139] | Temple K, Greenwood B, Inskip H, et al. Antibody response to pneumococcal capsular polysaccharide vaccine in African children[J]. Pediatr Infect Dis J, 1991, 10(5): 386–390. DOI:10.1097/00006454-199105000-00008 |

| [140] | Sell SH, Wright PF, Vaughn WK, et al. Clinical studies of pneumococcal vaccines in infants[J]. Rev Infect Dis, 1981(3 Suppl): S97–107. |

| [141] | Rose M, Hey C, Kujumdshiev S, et al. Immunogenicity of pneumococcal vaccination of patients with cochlear implants[J]. J Infect Dis, 2004, 190(3): 551–557. DOI:10.1086/422395 |

| [142] | Hey C, Rose MA, Kujumdshiev S, et al. Does the 23-valent pneumococcal vaccine protect cochlear implant recipients?[J]. Laryngoscope, 2005, 115(9): 1586–1590. DOI:10.1097/01.mlg.0000171016.82850.41 |

| [143] | Lee HJ, Kang JH, Henrichsen J, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of a 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine in healthy children and in children at increased risk of pneumococcal infection[J]. Vaccine, 1995, 13(16): 1533–1538. DOI:10.1016/0264-410X(95)00093-G |

| [144] | Kong YJ, Zhang W, Jiang ZW, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of a 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine in Chinese healthy population aged > 2 years:A randomized, double-blinded, active control, phase Ⅲ trial[J]. Hum Vaccin Immunother, 2015, 11(10): 2425–2433. DOI:10.1080/21645515.2015.1055429 |

| [145] | 美国食品药品管理局. 已批准的疫苗产品. Prevnar 13(肺炎球菌13价结合疫苗)[EB/OL]. http://www.fda.gov/BiologicsBloodVaccines/Vaccines/ApprovedProducts/ucm201667.htm. |

| [146] | EMA. 欧洲公共评估报告(EPAR): PCV10(2009年5月首次发布, 2011年10月更新)EMA/562289/2011[R]. EMA, 2011. |

| [147] | Song JY, Cheong HJ, Tsai TF, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of concomitant MF59-adjuvanted influenza vaccine and 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine administration in older adults[J]. Vaccine, 2015, 33(36): 4647–4652. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.05.003 |

| [148] | Agarwal N, Ollington K, Kaneshiro M, et al. Are immunosuppressive medications associated with decreased responses to routine immunizations? A systematic review[J]. Vaccine, 2012, 30(8): 1413–1424. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.11.109 |

| [149] | Kumar D, Welsh B, Siegal D, et al. Immunogenicity of pneumococcal vaccine in renal transplant recipients-three year follow-up of a randomized trial[J]. Am J Transplant, 2007, 7(3): 633–638. DOI:10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.01668.x |

| [150] | McCashland TM, Preheim LC, Gentry-Nielsen MJ. Pneumococcal vaccine response in cirrhosis and liver transplantation[J]. J Infect Dis, 2000, 181(2): 757–760. DOI:10.1086/315245 |

| [151] | Nordøy T, Husebekk A, Aaberge IS, et al. Humoral immunity to viral and bacterial antigens in lymphoma patients 4-10 years after high-dose therapy with ABMT.Serological responses to revaccinations according to EBMT guidelines[J]. Bone Marrow Transplant, 2001, 28(7): 681–687. DOI:10.1038/sj.bmt.1703228 |

| [152] | Sinisalo M, Vilpo J, ItäläM, et al. Antibody response to 7-valent conjugated pneumococcal vaccine in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia[J]. Vaccine, 2007, 26(1): 82–87. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.10.053 |

| [153] | Dransfield MT, Harnden S, Burton RL, et al. Long-term comparative immunogenicity of protein conjugate and free polysaccharide pneumococcal vaccines in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2012, 55(5): e35–44. DOI:10.1093/cid/cis513 |

| [154] | Mahmoodi M, Aghamohammadi A, Rezaei N, et al. Antibody response to pneumococcal capsular polysaccharide vaccination in patients with chronic kidney disease[J]. Eur Cytokine Netw, 2009, 20(2): 69–74. DOI:10.1684/ecn.2009.0153 |

| [155] | Butler JC, Breiman RF, Campbell JF, et al. Pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine efficacy.An evaluation of current recommendations[J]. JAMA, 1993, 280(15): 1826–1831. |

| [156] | Smets F, Bourgois A, Vermylen C, et al. Randomised revaccination with pneumococcal polysaccharide or conjugate vaccine in asplenic children previously vaccinated with polysaccharide vaccine[J]. Vaccine, 2007, 25(29): 5278–5282. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.05.014 |

| [157] | Lin PL, Michaels MG, Green M, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of the American Academy of Pediatrics-recommended sequential pneumococcal conjugate and polysaccharide vaccine schedule in pediatric solid organ transplant recipients[J]. Pediatrics, 2005, 116(1): 160–167. DOI:10.1542/peds.2004-2312 |

| [158] | Adamkiewicz TV, Silk BJ, Howgate J, et al. Effectiveness of the 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in children with sickle cell disease in the first decade of life[J]. Pediatrics, 2008, 121(3): 562–569. DOI:10.1542/peds.2007-0018 |

| [159] | Chan CY, Molrine DC, George S, et al. Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine primes for antibody responses to polysaccharide pneumococcal vaccine after treatment of Hodgkin's disease[J]. J Infect Dis, 1996, 173(1): 256–258. DOI:10.1093/infdis/173.1.256 |

| [160] | Gattringer R, Winkler H, Roedler S, et al. Immunogenicity of a combined schedule of 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine followed by a 23-valent polysaccharide vaccine in adult recipients of heart or lung transplants[J]. Transpl Infect Dis, 2011, 13(5): 540–544. DOI:10.1111/j.1399-3062.2011.00628.x |

| [161] | Black S, Shinefield H, Fireman B, et al. Efficacy, safety and immunogenicity of heptavalent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in children.Northern California Kaiser Permanente Vaccine Study Center Group[J]. Pediatr Infect Dis J, 2000, 19(3): 187–195. DOI:10.1097/00006454-200003000-00003 |

| [162] | Lucero MG, Dulalia VE, Nillos LT, et al. Pneumococcal conjugate vaccines for preventing vaccine-type invasive pneumococcal disease and X-ray defined pneumonia in children less than two years of age[J]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2009(4): CD004977. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD004977.pub2 |

| [163] | Eskola J, Kilpi T, Palmu A, et al. Efficacy of a pneumococcal conjugate vaccine against acute otitis media[J]. N Engl J Med, 2001, 344(6): 403–409. DOI:10.1056/NEJM200102083440602 |

| [164] | Grijalva CG, Nuorti JP, Arbogast PG, et al. Decline in pneumonia admissions after routine childhood immunisation with pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in the USA:a time-series analysis[J]. Lancet, 2007, 369(9568): 1179–1186. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60564-9 |

| [165] | Moore MR, Link-Gelles R, Schaffner W, et al. Effect of use of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in children on invasive pneumococcal disease in children and adults in the USA:analysis of multisite, population-based surveillance[J]. Lancet Infect Dis, 2015, 15(3): 301–309. DOI:10.1016/S1473-3099(14)71081-3 |

| [166] | Demczuk WHB, Martin I, Griffith A, et al. Serotype distribution of invasive Streptococcus pneumoniae in Canada after the introduction of the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, 2010-2012[J]. Can J Microbiol, 2013, 59(12): 778–788. DOI:10.1139/cjm-2013-0614 |

| [167] | Waight PA, Andrews NJ, Ladhani SN, et al. Effect of the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on invasive pneumococcal disease in England and Wales 4 years after its introduction:an observational cohort study[J]. Lancet Infect Dis, 2015, 15(5): 535–543. DOI:10.1016/S1473-3099(15)70044-7 |

| [168] | Harboe ZB, Dalby T, Weinberger DM, et al. Impact of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccination in invasive pneumococcal disease incidence and mortality[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2014, 59(8): 1066–1073. DOI:10.1093/cid/ciu524 |

| [169] | Ben-Shimol S, Greenberg D, Givon-Lavi N, et al. Early impact of sequential introduction of 7-valent and 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on IPD in Israeli children < 5 years:an active prospective nationwide surveillance[J]. Vaccine, 2014, 32(27): 3452–3459. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.03.065 |

| [170] | Simonsen L, Taylor RJ, Schuck-Paim C, et al. Effect of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on admissions to hospital 2 years after its introduction in the USA:a time series analysis[J]. Lancet Respir Med, 2014, 2(5): 387–394. DOI:10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70032-3 |

| [171] | Angoulvant F, Levy C, Grimprel E, et al. Early impact of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on community-acquired pneumonia in children[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2014, 58(7): 918–924. DOI:10.1093/cid/ciu006 |

| [172] | Pírez MC, Algorta G, Chamorro F, et al. Changes in hospitalizations for pneumonia after universal vaccination with pneumococcal conjugate vaccines 7/13 valent and Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate vaccine in a Pediatric Referral Hospital in Uruguay[J]. Pediatr Infect Dis J, 2014, 33(7): 753–759. DOI:10.1097/INF.0000000000000294 |

| [173] | Becker-Dreps S, Amaya E, Liu L, et al. Changes in childhood pneumonia and infant mortality rates following introduction of the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in Nicaragua[J]. Pediatr Infect Dis J, 2014, 33(6): 637–642. DOI:10.1097/INF.0000000000000269 |

| [174] | Zhao AS, Boyle S, Butrymowicz A, et al. Impact of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on otitis media bacteriology[J]. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol, 2014, 78(3): 499–503. DOI:10.1016/j.ijporl.2013.12.028 |

| [175] | Kaplan SL, Center KJ, Barson WJ, et al. Multicenter surveillance of Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates from middle ear and mastoid cultures in the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine era[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2015, 60(9): 1339–1345. DOI:10.1093/cid/civ067 |