文章信息

- 马恒敏, 王乐, 石菊芳, 应建明, 朱娟, 陈莉莉, 岳馨培, 龚继勇, 李晓, 王家林, 代敏.

- Ma Hengmin, Wang Le, Shi Jufang, Ying Jianming, Zhu Juan, Chen Lili, Yue Xinpei, Gong Jiyong, Li Xiao, Wang Jialin, Dai Min.

- 乳腺癌自然史模型研究系统评价:现状及构建中国人群特异性模型面临的挑战

- A systematic review of international simulation models on the natural history of breast cancer:current understanding and challenges for Chinese-population-specific model development

- 中华流行病学杂志, 2017, 38(10): 1419-1425

- Chinese Journal of Epidemiology, 2017, 38(10): 1419-1425

- http://dx.doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2017.10.025

-

文章历史

收稿日期: 2017-03-15

2. 100021 北京, 国家癌症中心/中国医学科学院北京协和医学院肿瘤病理科;

3. 250117 济南, 山东大学附属山东省肿瘤医院公共卫生科;

4. 730050 兰州, 甘肃省肿瘤医院肿瘤流行病学研究中心;

5. 450052 郑州大学第一附属医院病案管理科;

6. 266042 青岛市中心医院肿瘤防治中心

2. Department of Pathology, National Cancer Center/Cancer Hospital, National Cancer Center/Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College;

3. Department of Public Health, Shandong Cancer Hospital Affiliated to Shandong University, Jinan 250117, China;

4. Cancer Epidemiology Research Center, Gansu Provincial Cancer Hospital, Lanzhou 730050, China;

5. Department of Medical Records Management, the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou 450052, China;

6. Oncology Prevention Center, Qingdao Central Hospital, Qingdao 266042, China

乳腺癌严重威胁女性健康,我国每年新发病例达18.7万,死亡病例4.8万[1]。乳腺X线摄影筛查可降低乳腺癌死亡率且符合成本效果原则[2-3]。了解乳腺癌自然史,有助于筛查项目的效果评价,尤其是基于模型评价。本研究团队前期汇总了全球9项乳腺癌筛查随机对照试验,发现乳腺癌自然史状态及对应转移概率参数仍有限[4]。目前我国人群乳腺癌自然史模型研究十分有限,模型状态设置和参数多缺少循证支持和人群特异性[5]。因此,拟搜集全球乳腺癌自然史模型研究,归纳其方法、自然史状态设置及相关参数,结合数据可获得性提出适合我国人群的乳腺癌自然史模型建议,利于今后的筛查评价。

资料与方法1.文献检索策略:以PubMed和Cochrane Library英文数据库搜索全球乳腺癌自然史模型研究的相关文献。采用Mesh主题词和自由词(“breast neoplasms”、“breast cancer”、“costs and cost analysis”、“mass screening”、“models,statistical”、“natural history”等)相结合进行检索,时间限定为1980-2015年,文献语种为英语。为防止漏检,进一步追溯参考文献进行手工检索。此外,研究前期已检索万方、知网和维普等中文数据库,发现3项中国大陆人群乳腺癌筛查评价的模型研究[5],其中1项符合本研究纳入标准[6],因此未重复检索中文数据库。

2.文献纳入与排除标准:① 纳入标准:文献应同时满足癌种为乳腺癌,方法基于决策分析模型,且乳腺癌自然史健康状态设置明确;② 排除标准:包括综述、系统评价等非原创性研究;无乳腺癌自然史状态描述的相关研究;相同团队的自然史结构或参数重复研究;仅报告生存率或死亡率的预后研究。

3.资料提取:由2名研究人员根据提前制定的数据摘录表独立提取资料,意见不一致时提交课题组讨论决定,资料包括:发表年份、国家、样本量、覆盖年龄等;② 研究目的、模型类别、是否原创、有无调试等信息;③ 设置的自然史状态数量、起点和终点、乳腺癌前病变和癌症分类系统等信息;④ 不同起止状态间的一年进展概率参数、导管原位癌(ductal carcinoma in situ,DCIS)和浸润癌由临床前期至有临床症状出现的平均时间以及参数来源等信息。

4.统计学分析:采用Excel 2013软件进行数据处理,选取纳入研究中一年进展概率和临床前期出现临床症状的时间中位数和范围,以反映集中和离散趋势。

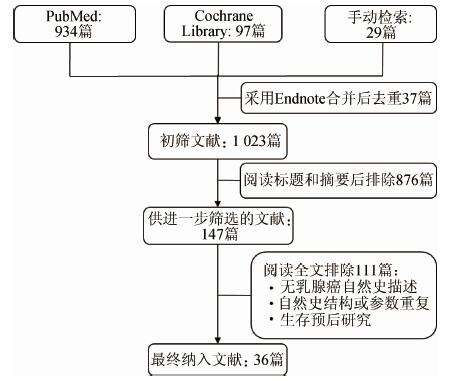

结果1.文献基本信息:初检删重后有1 023篇文献阅读标题和摘要,初筛后有147篇阅读全文,根据纳入、排除标准最终纳入36篇(图 1)。发表时间为1990-2015年[6-41],其中25篇发表于2005年之后[6, 18-41]。模拟样本量33 375~10 000 000,年龄多设定为≥40岁。人群以美洲(17篇)和欧洲(16篇)居多,部分研究涉及≥2个地区[15, 20, 22, 41]。模型主要用于筛查项目评价,卫生经济学和流行病学评价各有21篇和11篇,单纯自然史研究仅4篇。模型方法分为个体Markov(22篇)、队列Markov(10篇)和其他(4篇)。

|

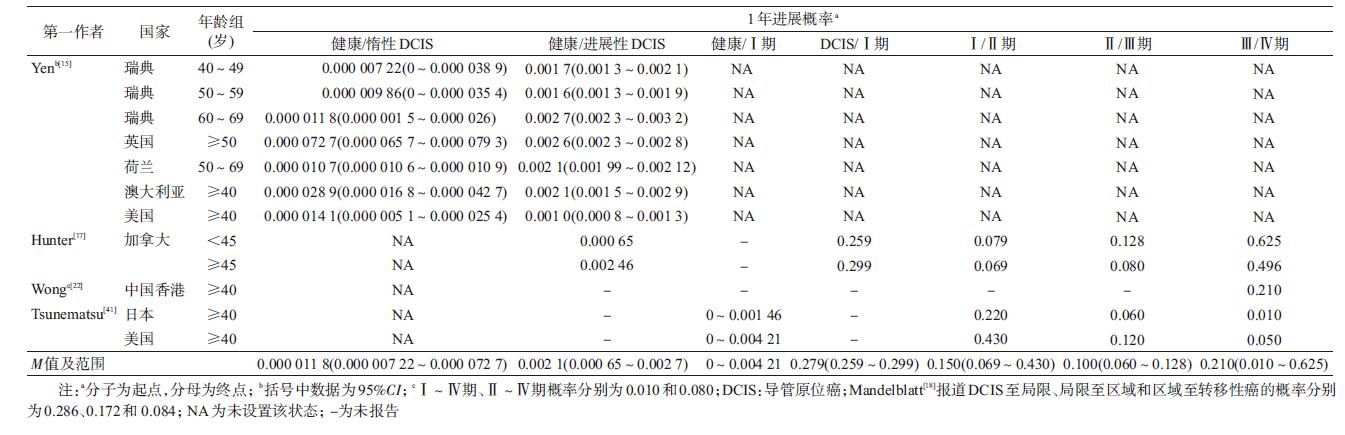

| 图 1 文献检索流程 |

2.乳腺癌自然史状态设置:36篇中报道自然史状态数目M=6(3~13),自然史状态包括“健康”(36篇)、DCIS(17篇)、乳腺浸润癌(36篇)和死亡(27篇)。DCIS状态可细分为14篇仅设置进展性DCIS(可发展为浸润癌)和3篇同时设置进展性和惰性DCIS(不发展为浸润癌)。明确报道浸润癌分类系统包括TNM分期(9篇)、肿瘤大小(9篇)和局限/区域/转移(5篇)。20篇文献报道1年进展概率或出现症状时间数据,参数来源多种,包括团队项目数据(14篇)[7-9, 11, 15-17, 28-29, 34-35, 37-38, 41]、已发表原创性研究(4篇)[15, 18, 37, 41]、公开数据库(4篇)[18, 22-23, 41]和参考其他模型(3篇)[10, 24-25]。见表 1。

3.乳腺癌自然史参数:

(1)不同状态间1年进展概率:5篇文献报道了状态间1年进展概率[15, 17-18, 22, 41],其中3篇报道了基于TNM分期的概率参数[17, 22, 41]:DCIS进展为Ⅰ期浸润癌的概率M=0.279(0.259~0.299),Ⅰ~Ⅱ期、Ⅱ~Ⅲ期、Ⅲ~Ⅳ期浸润癌的概率M值(范围)分别是0.150(0.069~0.430)、0.100(0.060~0.128)和0.210(0.010~0.625)。见表 2。

(2)DCIS从临床前期到出现临床症状的平均时间:7篇文献报道了不同年龄别的DCIS平均时间[7, 15-16, 23, 26, 35, 38],其中无中国人群数据。进展性DCIS不同年龄组(40~、50~、60~和≥70岁)的平均时间M值(范围)依次是2.82(0.00~7.00)、0.38(0.00~7.00)、0.30(0.00~0.70)和0.32(0.00~5.20)年;惰性DCIS结果稍有不同(表 3)。

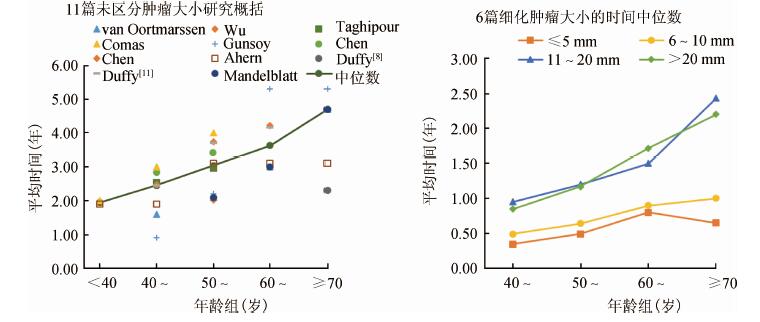

(3)浸润癌从临床前期到出现临床症状的平均时间:共计15篇文献报道了浸润癌平均时间[7-10, 16, 18, 23, 25-26, 28-29, 34-35, 37-38],其中6篇细化肿瘤大小[7, 10, 16, 23, 26, 35]。结果显示,浸润癌平均时间随年龄呈增加,不同年龄组(<40、40~、50~、60~和≥70岁)时间M值(范围)依次是1.95(1.90~2.00)、2.45(0.90~3.00)、3.04(2.02~4.00)、3.64(3.00~5.30)和4.70(2.30~5.30)年。细化肿瘤大小年龄别趋势与整体结果一致,大肿瘤组(≥11 mm)时间长于小肿瘤组(≤10 mm)。见图 2。

|

| 图 2 纳入文献中乳腺癌从临床前期到出现临床症状的平均时间在不同年龄组人群的变化 |

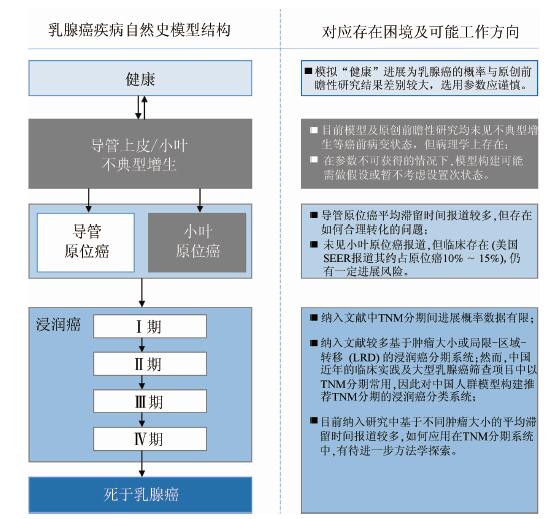

4.我国人群特异性乳腺癌自然史模型:基于本研究发现及结合我国实践,推荐我国人群特异性的乳腺癌自然史模型架构和下一步工作方向见图 3。

|

| 图 3 推荐的中国人群特异性乳腺癌自然史模型架构及工作方向 |

本文系统汇总了全球范围乳腺癌自然史的模型研究,发现此类研究逐年增多,并以Markov模型方法为主且多用于筛查项目评价,乳腺原位癌及癌前病变状态设置较少,浸润癌分类多样但参数有限。

纳入模型的研究中原位癌状态仅见DCIS设置,无其他状态。美国流行病学监测数据显示,2015年全美乳腺原位癌发病60 290例,其中小叶原位癌约占13.1%[3],提示其不可忽视。本研究团队前期开展筛查随机对照试验的系统综述发现,小叶原位癌的1年进展概率为0.018 1~0.035 8,高于DCIS对应概率[4]。同时,2012年WHO乳腺肿瘤组织学分类(第4版)中明确两类原位癌,即DCIS和小叶原位癌[42]。但新近发表的第8版AJCC癌症分期手册则认为“小叶原位癌归类良性病变,但存在恶变风险,且目前仍有争议”[43]。为此模型构建设置推荐保留小叶原位癌,但需补充其进展消退参数。此外,本文及前述系统综述均未见不典型增生等癌前病变状态[4],在缺少更多参数补充时,后期模型可能予以假设或不考虑设置。

本文纳入的文献较多基于肿瘤大小或“局限-进展-转移”的浸润癌分类系统。然而,近年我国临床实践及筛查项目中较为常用TNM分期[5, 44],因此对中国人群特异性模型构建推荐TNM分期系统仍存在一些问题:① 研究中TNM分期间转移概率参数有限且均非中国人群数据,与其他癌种一致[45-46],期待前瞻性筛查队列优化模型参数;② TNM分期综合了肿瘤大小、淋巴结和远处转移多个因素,且不同分期间可呈跳跃进展,如Wong等[22]报道由Ⅰ期直接进展至Ⅳ期,为模型的复杂性提出挑战;③ 一些研究报道了乳腺癌由临床前期到出现临床症状的平均时间,其对于确定筛查间隔意义较大[47-48],但如何将其转化为1年转移概率,仍需方法学方面的探索。

本研究存在局限性。① 仅在PubMed和Cochrane Library数据库检索文献,尽管补充了手工检索,仍可能漏检;② 纳入研究的1年转移概率M值及范围数据离散程度较大,可能与文献数量较少、国家别疾病负担存在差异、模型状态设置及参数来源等有关。

总之,本文在已有研究基础上结合我国实践,提出了适合我国人群的乳腺癌自然史模型架构,预期可应用于乳腺癌筛查项目的效果评价。然而,该框架仍有诸多不确定,有待进一步探讨。

利益冲突: 无

| [1] |

王乐, 张玥, 石菊芳, 等.

中国女性乳腺癌疾病负担分析[J]. 中华流行病学杂志, 2016, 37(7): 970–976.

Wang L, Zhang Y, Shi JF, et al. Disease burden of famale breast cancer in China[J]. Chin J Epidemiol, 2016, 37(7): 970–976. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2016.07.013 |

| [2] | Lauby-Secretan B, Scoccianti C, Loomis D, et al. Breast-cancer screening-viewpoint of the IARC working group[J]. N Engl J Med, 2015, 372(24): 2353–2358. DOI:10.1056/NEJMsr1504363 |

| [3] | Ward EM, Desantis CE, Lin CC, et al. Cancer statistics:breast cancer in situ[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2015, 65(6): 481–495. DOI:10.3322/caac.21321 |

| [4] |

岳馨培, 石菊芳, 毛阿燕, 等.

全球X线摄影筛查随机对照试验的乳腺癌疾病自然史研究[J]. 中华肿瘤杂志, 2017, 39(2): 154–160.

Yue XP, Shi JF, Mao AY, et al. Natural history of breast cancer:a systematic review of worldwide randomized controlled trials of mammography screening[J]. Chin J Oncol, 2017, 39(2): 154–160. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-3766.2017.02.017 |

| [5] |

王乐, 石菊芳, 黄慧瑶, 等.

我国乳腺癌筛查卫生经济学研究的系统评价[J]. 中华流行病学杂志, 2016, 37(12): 1662–1669.

Wang L, Shi JF, Huang HY, et al. Economic evaluation on breast cancer screening in mainland China:a systematic review[J]. Chin J Epidemiol, 2016, 37(12): 1662–1669. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2016.12.021 |

| [6] |

张峰, 罗立民, 鲍旭东, 等.

中国妇女乳腺X线钼靶摄影普查成本效益分析[J]. 肿瘤, 2012, 32(6): 440–447.

Zhang F, Luo LM, Bao XD, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of mammography screening for Chinese women[J]. Tumor, 2012, 32(6): 440–447. DOI:10.3781/j.issn.1000-7431.2012.06.008 |

| [7] | van Oortmarssen GJ, Habbema JDF, van der Maas PJ, et al. A model for breast cancer screening[J]. Cancer, 1990, 66(7):1601-1612. DOI:10.1002/1097-0142(19901001)66:7<1601::AID-CNCR2820660727>3.0.CO; 2-O. |

| [8] | Duffy SW, Chen HH, Tabar L, et al. Estimation of mean sojourn time in breast cancer screening using a markov chain model of both entry to and exit from the preclinical detectable phase[J]. Stat Med, 1995, 14(14): 1531–1543. DOI:10.1002/sim.4780141404 |

| [9] | Chen HH, Duffy SW, Tabar L. A markov chain method to estimate the tumour progression rate from preclinical to clinical phase, sensitivity and positive predictive value for mammography in breast cancer screening[J]. J R Stat Soc, 1996, 45(3): 307–317. DOI:10.2307/2988469 |

| [10] | Szeto KL, Devlin NJ. The cost-effectiveness of mammography screening:evidence from a microsimulation model for New Zealand[J]. Health Policy, 1996, 38(2): 101–115. DOI:10.1016/0168-8510(96)00843-3 |

| [11] | Duffy SW, Day NE, Tabár L, et al. Markov models of breast tumor progression:some age-specific results[J]. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr, 1997(22): 93–97. DOI:10.1093/jncimono/1997.22.93 |

| [12] | van den Akker-van Marle ME, Reep-van den Bergh CMM, Boer R, et al. Breast cancer screening in Navarra:interpretation of a high detection rate at the first screening round and a low rate at the second round[J]. Int J Cancer, 1997, 73(4):464-469. DOI:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19971114)73:4<464::AID-IJC2>3.0.CO; 2-Y. |

| [13] | van den Akker-van Marle E, de Koning H, Boer R, et al. Reduction in breast cancer mortality due to the introduction of mass screening in the Netherlands:comparison with the United Kingdom[J]. J Med Screen, 1999, 6(1): 30–34. DOI:10.1136/jms.6.1.30 |

| [14] | Carter KJ, Castro F, Kessler E, et al. A computer model for the study of breast cancer[J]. Comput Biol Med, 2003, 33(4): 345–360. DOI:10.1016/S0010-4825(03)00003-9 |

| [15] | Yen MF, Tabár L, Vitak B, et al. Quantifying the potential problem of overdiagnosis of ductal carcinoma in situ in breast cancer screening[J]. Eur J Cancer, 2003, 39(12): 1746–1745. DOI:10.1016/S0959-8049(03)00260-0 |

| [16] | Rijnsburger AJ, van Oortmarssen GJ, Boer R, et al. Mammography benefit in the Canadian National Breast Screening Study-2:a model evaluation[J]. Int J Cancer, 2004, 110(5): 756–762. DOI:10.1002/ijc.20143 |

| [17] | Hunter DJ, Drake SM, Shortt SE, et al. Simulation modeling of change to breast cancer detection age eligibility recommendations in Ontario, 2002-2021[J]. Cancer Detect Prev, 2004, 28(6): 453–460. DOI:10.1016/j.cdp.2004.08.003 |

| [18] | Mandelblatt JS, Schechter CB, Yabroff KR, et al. Toward optimal screening strategies for older women:costs, benefits, and harms of breast cancer screening by age, biology, and health status[J]. J Gen Intern Med, 2005, 20(6): 487–496. DOI:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0116.x |

| [19] | Shen Y, Parmigiani G. A model-based comparison of breast cancer screening strategies:mammograms and clinical breast examinations[J]. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 2005, 14(2): 529–532. DOI:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0499 |

| [20] | Groot MT, Baltussen R, Uyl-de Groot CA, et al. Costs and health effects of breast cancer interventions in epidemiologically different regions of Africa, North America, and Asia[J]. Breast J, 2006, 12(Suppl 1): S81–90. DOI:10.1111/j.1075-122X.2006.00206.x |

| [21] | Lee S, Zelen M. A stochastic model for predicting the mortality of breast cancer[J]. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr, 2006(36): 79–86. DOI:10.1093/jncimonographs/lgj011 |

| [22] | Wong IOL, Kuntz KM, Cowling BJ, et al. Cost effectiveness of mammography screening for Chinese women[J]. Cancer, 2007, 110(4): 885–895. DOI:10.1002/cncr.22848 |

| [23] | Okonkwo QL, Draisma G, der Kinderen A, et al. Breast cancer screening policies in developing countries:a cost-effectiveness analysis for India[J]. J Natl Cancer Inst, 2008, 100(18): 1290–1300. DOI:10.1093/jnci/djn292 |

| [24] | Rojnik K, Naveršnik K, Mateović-Rojnik T, et al. Probabilistic cost-effectiveness modeling of different breast cancer screening policies in Slovenia[J]. Value Health, 2008, 11(2): 139–148. DOI:10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00223.x |

| [25] | Ahern CH, Shen Y. Cost-effectiveness analysis of mammography and clinical breast examination strategies:a comparison with current guidelines[J]. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 2009, 18(3): 718–725. DOI:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0918 |

| [26] | de Gelder R, Bulliard JL, de Wolf C, et al. Cost-effectiveness of opportunistic versus organised mammography screening in Switzerland[J]. Eur J Cancer, 2009, 45(1): 127–138. DOI:10.1016/j.ejca.2008.09.015 |

| [27] | Baeten SA, Baltussen RMPM, Uyl-de Groot CA, et al. Incorporating equity-efficiency interactions in cost-effectiveness analysis-three approaches applied to breast cancer control[J]. Value Health, 2010, 13(5): 573–579. DOI:10.1111/j.1524-4733.2010.00718.x |

| [28] | Chen YL, Brock G, Wu DF. Estimating key parameters in periodic breast cancer screening-application to the Canadian national breast screening study data[J]. Cancer Epidemiol, 2010, 34(4): 429–433. DOI:10.1016/j.canep.2010.04.001 |

| [29] | Wu JCY, Hakama M, Anttila A, et al. Estimation of natural history parameters of breast cancer based on non-randomized organized screening data:subsidiary analysis of effects of inter-screening interval, sensitivity, and attendance rate on reduction of advanced cancer[J]. Breast Cancer Res Treat, 2010, 122(2): 553–566. DOI:10.1007/s10549-009-0701-x |

| [30] | Carles M, Vilaprinyo E, Cots F, et al. Cost-effectiveness of early detection of breast cancer in Catalonia (Spain)[J]. BMC Cancer, 2011, 11(1): 192. DOI:10.1186/1471-2407-11-192 |

| [31] | Schousboe JT, Kerlikowske K, Loh A, et al. Personalizing mammography by breast density and other risk factors for breast cancer:analysis of health benefits and cost-effectiveness[J]. Ann Intern Med, 2011, 155(1): 10–20. DOI:10.7326/0003-4819-155-1-201107050-00003 |

| [32] | Zelle SG, Nyarko KM, Bosu WK, et al. Costs, effects and cost-effectiveness of breast cancer control in Ghana[J]. Trop Med Int Health, 2012, 17(8): 1031–1043. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-3156.2012.03021.x |

| [33] | Souza FH, Polanczyk CA. Is age-targeted full-field digital mammography screening cost-effective in emerging countries? A micro simulation model[J]. Springerplus, 2013, 2: 366. DOI:10.1186/2193-1801-2-366 |

| [34] | Taghipour S, Banjevic D, Miller AB, et al. Parameter estimates for invasive breast cancer progression in the Canadian national breast screening study[J]. Br J Cancer, 2013, 108(3): 542–548. DOI:10.1038/bjc.2012.596 |

| [35] | Tan KHX, Simonella L, Wee HL, et al. Quantifying the natural history of breast cancer[J]. Br J Cancer, 2013, 109(8): 2035–2043. DOI:10.1038/bjc.2013.471 |

| [36] | Zelle SG, Vidaurre T, Abugattas JE, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of breast cancer control interventions in Peru[J]. PLoS One, 2013, 8(12): e82575. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0082575 |

| [37] | Comas M, Arrospide A, Mar J, et al. Budget impact analysis of switching to digital mammography in a population-based breast cancer screening program:a discrete event simulation model[J]. PLoS One, 2014, 9(5): e97459. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0097459 |

| [38] | Gunsoy NB, Garcia-Closas M, Moss SM. Estimating breast cancer mortality reduction and overdiagnosis due to screening for different strategies in the United Kingdom[J]. Br J Cancer, 2014, 110(10): 2412–2419. DOI:10.1038/bjc.2014.206 |

| [39] | Niëns LM, Zelle SG, Gutiérrez-Delgado C, et al. Cost-effectiveness of breast cancer control strategies in central America:the cases of Costa Rica and Mexico[J]. PLoS One, 2014, 9(4): e95836. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0095836 |

| [40] | Sankatsing VDV, Heijnsdijk EAM, van Luijt PA, et al. Cost-effectiveness of digital mammography screening before the age of 50 in the Netherlands[J]. Int J Cancer, 2015, 137(8): 1990–1999. DOI:10.1002/ijc.29572 |

| [41] | Tsunematsu M, Kakehashi M. An analysis of mass screening strategies using a mathematical model:comparison of breast cancer screening in Japan and the United States[J]. J Epidemiol, 2015, 25(2): 162–171. DOI:10.2188/jea.JE20140047 |

| [42] | Lakhani SR, Ellis IO, Schnitt SJ, et al.WHO classification of tumours of the breast[M]. 4th ed. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2012. |

| [43] | Giuliano AE, Connolly JL, Edge SB, et al. Breast cancer-major changes in the American joint committee on cancer eighth edition cancer staging manual[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2017, 67(4): 290–303. DOI:10.3322/caac.21393 |

| [44] | Li J, Zhang BN, Fan JH, et al. A nation-wide multicenter 10-year (1999-2008) retrospective clinical epidemiological study of female breast cancer in China[J]. BMC Cancer, 2011, 11: 364. DOI:10.1186/1471-2407-11-364 |

| [45] |

石菊芳, 代敏.

中国癌症筛查的卫生经济学评价[J]. 中华预防医学杂志, 2017, 51(2): 107–111.

Shi JF, Dai M. Health economic evaluation of cancer screening in China[J]. Chin J Prev Med, 2017, 51(2): 107–111. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-9624.2017.02.002 |

| [46] |

李志芳, 黄慧瑶, 石菊芳, 等.

结直肠癌疾病自然史模型研究的系统综述:体系分类、参数分析及推荐构建我国人群特异性模型[J]. 中华流行病学杂志, 2017, 38(2): 253–260.

Li ZF, Huang HY, Shi JF, et al. A systematic review of worldwide natural history models of colorectal cancer:classification, transition rate and a recommendation for developing Chinese population-specific model[J]. Chin J Epidemiol, 2017, 38(2): 253–260. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2017.02.024 |

| [47] | Jiang H, Walter SD, Brown PE, et al. Estimation of screening sensitivity and sojourn time from an organized screening program[J]. Cancer Epidemiol, 2016, 44: 178–185. DOI:10.1016/j.canep.2016.08.021 |

| [48] | Oeffinger KC, Fontham ETH, Etzioni R, et al. Breast cancer screening for women at average risk:2015 guideline update from the American Cancer Society[J]. JAMA, 2015, 314(15): 1599–1614. DOI:10.1001/jama.2015.12783 |

2017, Vol. 38

2017, Vol. 38