文章信息

- 郭乐倩, 章琦, 赵豆豆, 王玲玲, 陈宇, 米白冰, 党少农, 颜虹.

- Guo Leqian, Zhang Qi, Zhao Doudou, Wang Lingling, Chen Yu, Mi Baibing, Dang Shaonong, Yan Hong.

- 孕期空气污染物暴露与活产单胎新生儿出生体重的关联性分析

- Relationship between air pollution exposure during pregnancy and birth weight of term singleton live-birth newborns

- 中华流行病学杂志, 2017, 38(10): 1399-1403

- Chinese Journal of Epidemiology, 2017, 38(10): 1399-1403

- http://dx.doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2017.10.021

-

文章历史

收稿日期: 2017-02-15

2. 718000 榆林市第一医院病案科

2. Medical Records Department, The First Hospital of Yulin, Yulin 718000, China

出生体重是与围产结局关系密切的一个重要因素。其中,低出生体重(LBW,出生体重<2 500 g)是新生儿死亡率最重要的预报因子,也是衡量社会发展和卫生状况的重要指标[1]。近年来,空气污染与新生儿出生体重的关联研究成为新的热点,但因涉及的污染物种类、暴露的孕期不一致,出现相互矛盾的结果[2-3]。此外,国际上已有气象因素,如温度、相对湿度等对于新生儿不良出生结局影响的报道[4-5],而气象因素又可直接影响大气颗粒物的浓度[6]。由于国内有关联合气象因素分析大气污染物对出生体重的研究罕见报道。为此,本研究基于陕西省出生缺陷现况及其危险因素调查项目数据,分析西安市气象因素和室外空气污染物暴露与活产单胎新生儿出生体重的关联性。

对象与方法1.研究对象:根据人口密集程度和生育水平,采用多阶段随机抽样方法,于2013年6-11月随机抽取西安市5个区(莲湖区、灞桥区、雁塔区、新城区、碑林区),每个区随机抽取3个街道办事处,每个街道办事处随机抽取6个社区,每个社区随机调查60例妇女。纳入标准:① 2010-2013年曾经妊娠的15~49岁育龄妇女;② 妊娠结局明确,为活产、单胎;③ 婴儿出生体重数据完整。调查对象均签署知情同意书。最终共纳入4 631例婴儿。

2.研究方法:采用自行设计的调查问卷,由西安交通大学公共卫生学院硕士研究生及本科生面对面调查妇女的社会人口学信息、婚育史(孕次、产次等)、妊娠结局资料(每次妊娠终止日期、终止孕周、妊娠结局、胎婴儿性别、胎婴儿是否存活、胎婴儿出生体重等)。从西安市环境监测站下载2010-2013年空气质量日监测数据,包括主要污染物SO2、NO2和PM10每个监测站点逐日平均浓度及全市平均浓度等。根据产妇居住城区一一对应,估计孕期空气污染暴露量。另外,根据国际上通行方法[7],按照每例新生儿的出生时间和其母亲孕周,推算末次月经时间,以计算孕早、中、晚期上述3种污染物的平均暴露量。气象资料数据由兰州大学气象学院提供,包括西安市2010年1月至2013年12月逐日不同时段(08:00、12:00、20:00)的风速、气温、相对湿度等。计算孕早、中、晚期3种气象资料的平均水平[5]。

3.统计学分析:采用EpiData 3.1软件建立数据库,SPSS 17.0软件进行统计分析。空气污染物浓度及气象资料由x±s、百分位数描述。按照影响出生体重的因子分别计算平均出生体重和LBW发生率;前者组间两组比较采用t检验,多组比较采用方差分析(F检验),差异有统计学意义者进一步采用χ2检验。空气污染与出生体重的关联性采用多元线性回归分析,其中自变量依次分为“单污染物”、“双污染物”和“三污染物”。模型一未调整其他因素,模型二调整了与母亲和新生儿有关的一般因素,模型三在模型二的基础上继续调整了气象因素。检验水准α=0.05。

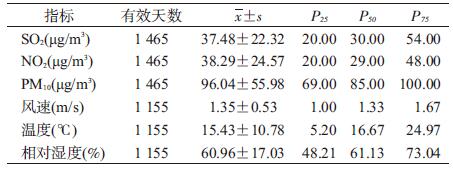

结果1.污染物、气象及暴露状况:2010-2013年西安市SO2日浓度为(37.48±22.32)μg/m3,NO2为(38.29±24.57)μg/m3,PM10为(96.04±55.98)μg/m3。风速为(1.35±0.53)m/s,温度为(15.43±10.78)℃,相对湿度为(60.96±17.03)%(表 1)。每名母亲孕早期接触SO2水平为(37.38±18.02)μg/m3,NO2为(30.32±12.96)μg/m3,PM10为(85.90±23.90)μg/m3,各孕期其他污染物指标及气象资料见表 2。

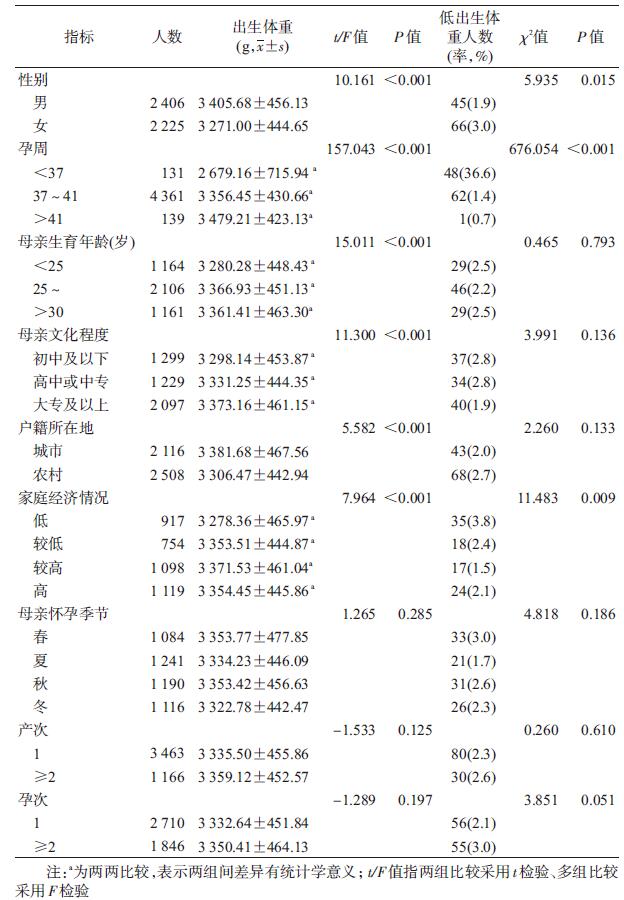

2.出生体重影响因素:分析显示婴儿性别为男、孕周越长、母亲生育年龄相对较高(≥25岁)、母亲文化程度越高、户籍为城市、家庭经济较好者其婴儿出生体重较高(表 3)。其中婴儿性别、母亲孕周、家庭经济状况对LBW发生率影响的差异有统计学意义(P<0.05)。

3.污染物暴露量与出生体重的关联分析:以出生体重为因变量,孕期污染物(单污染物、双污染物、三污染物)暴露量分别为自变量,采用多元线性回归方程拟合模型(模型一)。在此基础上,将单因素分析中差异有统计学意义的因子作为自变量,拟合调整模型(模型二)。在模型二的基础上调整3种气象因素,拟合出模型三。结果见表 4。不考虑污染物的协同作用时,模型一未发现差异有统计学意义;模型二、三中孕中期NO2和PM10暴露对出生体重影响的差异均有统计学意义(P<0.05),孕晚期NO2对出生体重影响的差异也有统计学意义(P<0.05),且污染物对出生体重的影响均呈负效应。考虑污染物的协同作用时,模型二和三显示孕早期引入PM10后,NO2对出生体重影响的差异有统计学意义(P<0.05),但效应呈正相关;孕中期引入SO2后,NO2和PM10暴露对出生体重影响的差异均有统计学意义(P<0.05);孕晚期引入SO2和(或)PM10后,NO2对出生体重的影响差异有统计学意义(P<0.05)。即孕中期接触NO2的平均浓度每增加10 μg/m3,出生体重可减少13.3 g(模型二减少10.9 g),接触PM10每增加10 μg/m3,出生体重减少6.6 g(模型二减少5.9 g);孕晚期接触NO2每增加10 μg/m3,出生体重减少13.7 g(模型二减少9.8 g)。

本研究联合气象因素后探讨了西安市SO2、NO2、PM10污染水平与新生儿出生体重之间的关联。结果显示新生儿性别为男、孕周越长、母亲生育年龄相对较高(≥25岁)、母亲文化程度越高、户籍在城市、家庭经济情况较好者新生儿出生体重较高。控制了上述因素及3种气象因素(风速、温度、相对湿度)后发现,孕中期NO2、PM10的暴露水平以及孕晚期NO2的暴露水平是新生儿出生体重的重要影响因子。

在多元线性回归分析中拟合3种模型。模型一未调整任何混杂,结果显示差异无统计学意义;模型二调整了孕周、性别、母亲生育年龄等一般混杂因素,模型三在此基础上继续调整了气象因素。结果发现,考虑污染物的协同作用后,孕早期出现NO2对出生体重存在正向效应,这与钱耐思等[8]在上海市的研究结果及相应的生理机制矛盾。但在Stieb等[9]的研究中也出现污染物SO2的暴露会增加出生体重。原因可能为地理环境不同导致结果不同,说明差异有统计学意义并不能完全反映真实情况。孕中期接触NO2的平均浓度每增加10 μg/m3,出生体重会减少13.3 g(模型二减少10.9 g),接触PM10每增加10 μg/m3,出生体重减少6.6 g(模型二减少5.9 g);孕晚期接触NO2每增加10 μg/m3,出生体重减少13.7 g(模型二减少9.8 g)。可见控制不同的混杂因素对其结果有重要影响。已有多项研究如Ghosh等[10]分析表明NO2对出生体重的影响多集中在孕中、晚期,与本文结果一致。对于PM10而言,本研究只发现其在孕中期暴露与出生体重有关,而与Xu等[11]发现孕早、中期暴露于PM10均可增加LBW发生风险的研究结果不完全一致。另外,本研究表明孕早、中、晚期暴露于SO2对LBW发生的影响均无统计学意义,该结果与Capobussi等[12]研究一致。出现上述结局异质性的原因除了混杂因素的纳入不同外,还可能与不同研究地区的空气污染水平有差异、人群对空气污染的易感性不同,或者污染物个体水平暴露评估方法、研究对象的入选标准、结局指标的测量以及最终使用的衡量空气污染与出生体重关联性的统计学方法不同有关。

目前关于空气污染对出生体重影响的生物学机制尚未明确。

本研究尚有不足,如利用环境监测资料分析时,只是对个体暴露水平进行了估算,存在一定的误差。本研究主要发现控制了气象因素及母亲婴儿个体差异后,孕中期NO2、PM10的暴露水平以及孕晚期NO2的暴露对婴儿出生体重具有负效应。今后可进一步分析各污染物之间的交互作用,深入探讨空气污染物对出生体重作用的具体生物学机制。

利益冲突: 无

| [1] | Yorifuji T, Kashima S, Doi H. Outdoor air pollution and term low birth weight in Japan[J]. Environ Int, 2015, 74: 106–111. DOI:10.1016/j.envint.2014.09.003 |

| [2] | Salihu HM, August EM, Mbah AK, et al. Effectiveness of a federal healthy start program in reducing the impact of particulate air pollutants on feto-infant morbidity outcomes[J]. Matern Child Health J, 2012, 16(8): 1602–1611. DOI:10.1007/s10995-011-0854-1 |

| [3] | Laurent O, Wu J, Li LF, et al. Investigating the association between birth weight and complementary air pollution metrics:a cohort study[J]. Environ Health, 2013, 12: 18. DOI:10.1186/1476-069X-12-18 |

| [4] | Giorgis-Allemand L, Pedersen M, Bernard C, et al. The influence of meteorological factors and atmospheric pollutants on the risk of preterm birth[J]. Am J Epidemiol, 2017, 185(4): 247–258. DOI:10.1093/aje/kww141 |

| [5] | Zhao N, Qiu J, Zhang YQ, et al. Ambient air pollutant PM10 and risk of preterm birth in Lanzhou, China[J]. Environ Int, 2015, 76: 71–77. DOI:10.1016/j.envint.2014.12.009 |

| [6] | Yin JP, Yin NB, Liu L, et al. Seasonal variation in birth months of patients with oral-facial clefts[J]. J Craniofac Surg, 2013, 24(1): e18–21. DOI:10.1097/SCS.0b013e3182670045 |

| [7] |

赵庆国, 李兵, 杜玉开.

空气污染物对出生体重影响的研究[J]. 中国预防医学杂志, 2008, 9(7): 607–613.

Zhao QG, Li B, Du YK. Study on the association between air pollutants and birth weight[J]. Chin Prev Med, 2008, 9(7): 607–613. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1009-6639.2008.07.007 |

| [8] |

钱耐思, 虞慧婷, 蔡任之, 等.

上海市母亲孕早期空气污染物暴露与新生儿出生体重的关系[J]. 环境与职业医学, 2016, 33(9): 827–832.

Qian NS, Yu HT, Cai RZ, et al. Association between maternal air pollution exposure during first trimester and birth weight in Shanghai[J]. J Environ Occup Med, 2016, 33(9): 827–832. DOI:10.13213/j.cnki.jeom.2015.16123 |

| [9] | Stieb DM, Chen L, Eshoul M, et al. Ambient air pollution, birth weight and preterm birth:a systematic review and Meta-analysis[J]. Environ Res, 2012, 117: 100–111. DOI:10.1016/j.envres.2012.05.007 |

| [10] | Ghosh JKC, Wilhelm M, Su J, et al. Assessing the influence of traffic-related air pollution on risk of term low birth weight on the basis of land-use-based regression models and measures of air toxics[J]. Am J Epidemiol, 2012, 175(12): 1262–1274. DOI:10.1093/aje/kwr469 |

| [11] | Xu XH, Sharma RK, Talbott EO, et al. PM10 air pollution exposure during pregnancy and term low birth weight in Allegheny County, PA, 1994-2000[J]. Int Arch Occup Environ Health, 2011, 84(3): 251–257. DOI:10.1007/s00420-010-0545-z |

| [12] | Capobussi M, Tettamanti R, Marcolin L, et al. Air pollution impact on pregnancy outcomes in Como, Italy[J]. J Occup Environ Med, 2016, 58(1): 47–52. DOI:10.1097/JOM.0000000000000630 |

2017, Vol. 38

2017, Vol. 38