文章信息

- 郭玲玲, 申嘉欣, 汝首杭, 王颖, 李玫, 冯永亮, 张萍, 邬惟为, 王素萍, 张亚玮, 杨海澜.

- Guo Lingling, Shen Jiaxin, Ru Shouhang, Wang Ying, Li Mei, Feng Yongliang, Zhang Ping, Wu Weiwei, Wang Suping, Zhang Yawei, Yang Hailan.

- 孕前体质指数对围孕期增补叶酸与小于胎龄儿关系影响的研究

- Association between periconceptional folic acid supplementation and small for gestational age birth based on pre-pregnancy body mass index

- 中华流行病学杂志, 2017, 38(9): 1263-1268

- Chinese journal of Epidemiology, 2017, 38(9): 1263-1268

- http://dx.doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2017.09.024

-

文章历史

收稿日期: 2017-01-19

2. 耶鲁大学公共卫生学院环境健康科学系;

3. 030001 太原, 山西医科大学第一医院妇产科

2. Division of Environmental Health Sciences, School of Public Health, Yale University, USA;

3. Obstetrics and Gynecology of First Affiliated Hospital, Shanxi Medical University, Taiyuan 030001, China

小于胎龄儿(SGA)是指出生体重低于同胎龄平均体重的第10百分位(P10)者,是新生儿死亡的重要原因,并影响儿童期、青春期体格和智力发育[1],也与成年后发生慢性疾病密切相关[2]。SGA的发生受母亲、胎儿等多方面因素影响[3]。研究表明,母亲围孕期增补叶酸不仅预防神经管畸形[4],还可预防SGA的发生[5]。孕前BMI是衡量孕妇营养状况的重要指标。研究显示,孕前BMI过低或过高与SGA的发生有关[6-7]。由此,孕前BMI可能会影响围孕期增补叶酸与SGA的关系。目前国内主要是单纯关于围孕期增补叶酸与SGA的研究[8],而国外的相关研究均未明确增补叶酸种类以及剂量且主要按孕前BMI分为两组进行探讨[9-10]。为此,本研究采用较大样本量探讨孕前不同BMI者中围孕期增补叶酸与SGA的关系,并分析增补叶酸种类和剂量,为预防控制SGA提供参考。

对象与方法1.研究对象:以2012年3月至2016年9月在山西医科大学第一医院产科分娩的孕妇作为研究队列,通过采集病历信息及问卷调查收集孕妇产前、产中及产后的流行病学和临床资料,同时收集新生儿基本信息。纳入标准:① 孕妇无精神性疾患,表达和理解能力正常;② 单胎活产,无出生缺陷。排除标准为死胎/产、流产、双/多胎者,<20孕周和大于胎龄儿。最终获得8 523份有效问卷。共收集1 066例SGA作为病例组,7 457例适于胎龄儿(AGA)作为对照组。研究经山西医科大学伦理委员会审查批准,所有研究对象均签署知情同意书。

2.研究方法:由培训合格的调查员采用统一的调查问卷进行面对面调查,并查阅病历相关信息,问卷内容包括孕妇一般人口学特征、妊娠情况、围产期保健及新生儿基本信息等。孕前体重由问卷调查获得,身高为入院时统一测量,并根据公式计算孕前BMI。采用巢式病例对照方法,探讨孕前不同BMI水平的孕妇围孕期增补叶酸与SGA的关系。

3.标准及分组:出生体重低于同胎龄平均体重的P10者为SGA,位于同胎龄平均出生体重的P10~90者为AGA[11]。根据2002年中国肥胖问题工作组提出的成年人适宜BMI(kg/m2)范围标准分组:孕前BMI<18.5为体重较低组、18.5≤BMI<24.0为体重正常组、24.0≤BMI<28.0为超重组、BMI≥28.0为肥胖组[12]。根据孕期增补叶酸情况分为未增补叶酸(整个孕期均未增补叶酸,即孕前/早/中/晚期均未增补叶酸)和围孕期增补叶酸(单纯孕前或孕早期增补叶酸,并坚持增补叶酸≥1个月)2种类型。根据围孕期增补叶酸种类主要分为单纯增补400 μg叶酸片(FA)组和单纯增补含400 μg叶酸的复合维生素(MV)组。

4.统计学分析:采用EpiData 3.1软件录入数据及逻辑纠错,采用SAS 9.4软件进行数据清理及统计学分析,单因素分析采用χ2检验,多因素分析采用非条件logistic回归,P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。

结果1.一般特征及叶酸增补情况:8 523名单胎活产孕妇年龄14~59岁,平均(29.45±4.57)岁。孕周为28~44周,平均(38.42±2.00)周。78.27%的孕妇居住在城市。59.40%家庭人均月收入在中等水平(2 000~4 000元)。新生儿平均出生体重(3 085.77±515.64)g,孕前BMI为(21.59±3.22)kg/m2。SGA平均出生体重(2 301.42±494.77)g,孕前BMI为(21.70±3.32)kg/m2。AGA平均出生体重(3 195.69±413.00)g,孕前BMI为(21.57±3.21)kg/m2。1 280人(15.02%)未增补叶酸,5 547人(65.08%)围孕期增补叶酸,此外其他增补者1 696人(19.90%)。围孕期单纯增补FA者5 437人,单纯增补MV者72人。

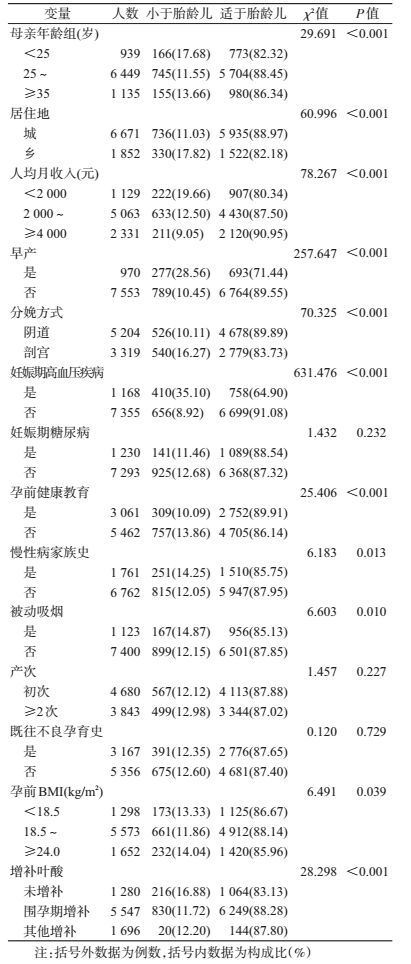

2. SGA的单因素分析:孕妇年龄、居住地、家庭人均月收入、早产、妊娠期高血压疾病、分娩方式、孕前健康教育、慢性病家族史、被动吸烟、孕前BMI和围孕期增补叶酸与SGA的发生有关,差异均有统计学意义(P<0.05),见表 1。

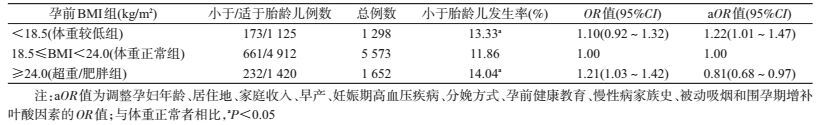

3.孕前BMI水平与SGA的关系:孕前不同BMI组SGA发生率差异有统计学意义(χ2=6.491,P= 0.039)。非条件logistic回归分析显示,调整孕妇年龄等因素后,孕前体重较低者(BMI<18.5 kg/m2)是SGA发生的危险因素(OR=1.22,95%CI:1.01~1.47),孕前超重/肥胖者(BMI≥24.0 kg/m2)可降低SGA的发生风险(OR=0.81,95%CI:0.68~0.97),见表 2。

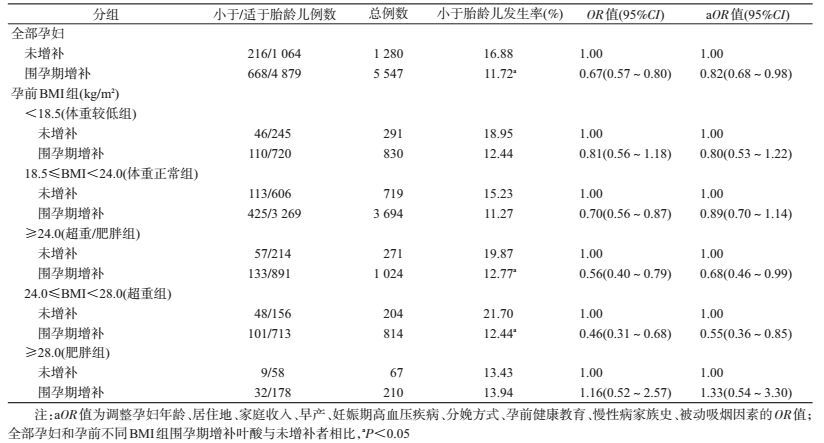

4.孕前不同BMI组围孕期增补叶酸与SGA的关系:围孕期增补叶酸的孕妇其新生儿SGA的发生率低于未增补叶酸者,差异有统计学意义(χ2=26.264,P<0.001)。非条件logistic回归分析显示,调整孕妇年龄等因素后,围孕期增补叶酸是SGA的保护因素(OR=0.82,95%CI:0.68~0.98)。按孕前BMI分层后显示,孕前超重组[24.0≤BMI(kg/m2)<28.0]围孕期增补叶酸可降低SGA的发生风险(OR=0.55,95%CI:0.36~0.85),而其他BMI组中未发现其有关(表 3)。

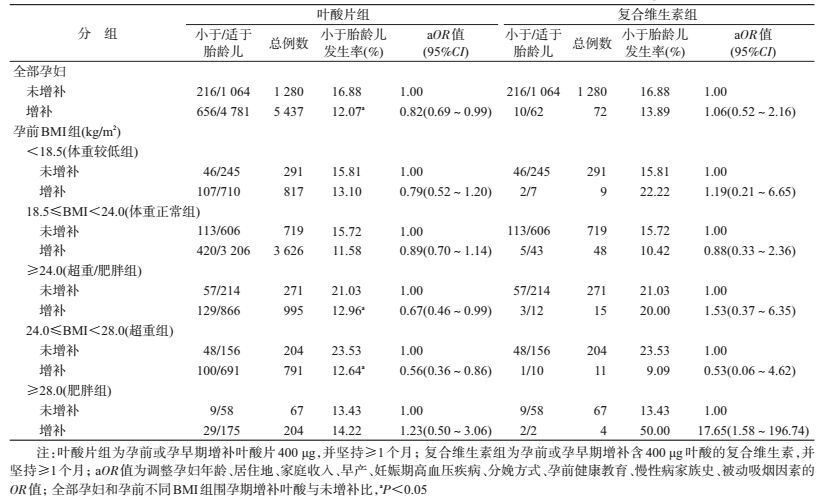

5.孕前不同BMI组围孕期分别单纯增补FA和MV与SGA的关系:非条件logistic回归分析显示,调整孕妇年龄等因素后,围孕期单纯增补FA是SGA的保护因素(OR=0.82,95%CI:0.69~0.99)。按孕前BMI分层后发现,孕前超重组[24.0≤BMI(kg/m2)<28.0]围孕期单纯增补FA可降低SGA的发生风险(OR=0.56,95%CI:0.36~0.86),而在其他BMI组中未发现其有关。围孕期单纯增补MV与SGA无关(表 4)。

孕妇叶酸营养状况与胎儿生长发育密切相关[13]。本研究显示孕妇围孕期增补叶酸可降低SGA的发生风险,与Timmermans等[14]研究结果一致。孕前BMI是衡量孕妇营养状态的一项指标,也是可以监测控制的因素。有研究报道女性孕前BMI<18.5 kg/m2是SGA的危险因素[6],孕妇体重过高会降低SGA的发生风险[7],与本研究结果相一致。因此,母亲孕前BMI可能会对围孕期增补叶酸与SGA的关系产生影响。

本研究显示孕前超重者围孕期增补叶酸发生SGA的风险明显降低,而其他BMI组中未发现围孕期增补叶酸与SGA有关。Catov等[9]研究显示,孕前BMI<30 kg/m2者围孕期增补MV可降低SGA的发生风险(OR=0.54,95%CI:0.32~0.91),而孕前BMI≥30 kg/m2者中未发现其对SGA有作用。Martinussen等[10]研究表明,孕前BMI<25 kg/m2者孕前或孕早期增补叶酸与SGA无关。提示,围孕期增补叶酸与SGA的关系受到孕前BMI的影响,但其原因目前尚不清楚。Mojtabai[15]研究表明,孕前BMI>30 kg/m2孕妇需要每天额外补充350 μg叶酸以达到与BMI<20 kg/m2的孕妇相同血清叶酸水平。研究表明,母亲较高的BMI与较低的血清叶酸浓度呈正相关[16],其原因可能为肥胖导致雌激素增加,而后者可降低体内血清叶酸浓度[17],可能影响表观遗传的调节(如DNA甲基化),最终使得对SGA的保护作用减弱或无效。所以,与BMI<28 kg/m2者增补相同的叶酸,BMI≥28 kg/m2者可能对SGA的保护作用减弱或无效。

本研究结果还表明,孕前/早期单纯增补FA对SGA发生起保护作用。Hodgetts等[18]研究也显示相同结果。本研究发现孕前超重者围孕期单纯增补FA可降低SGA的发生,而其他BMI组未发现有降低SGA的作用。提示孕前BMI可能会对围孕期增补叶酸与SGA的关系产生影响。Wang等[19]研究表明,体重较低/正常的孕妇围孕期增补FA可有效降低不良出生结局的发生,但是主要是针对发生神经管缺陷。本文孕前/早期单纯增补MV与SGA无关,其原因可能为样本数量少或由于其他维生素的存在对叶酸的作用产生干扰所致。

本研究存在不足。如肥胖组孕妇和单纯增补MV组人数相对较少,结果未能充分说明两组中孕妇围孕期增补叶酸与SGA的关系;本研究主要针对孕前、早期增补叶酸的情况,未探讨孕中、晚期的情况。

总之,本研究按照孕前不同BMI亚组进行围孕期增补叶酸对SGA的分析,发现孕前超重者围孕期单纯增补FA(400 μg叶酸片)可降低SGA的发生风险,而在其他BMI组未发现围孕期增补叶酸与SGA有关,提示孕前BMI可能影响围孕期增补叶酸与SGA发生的关系。

利益冲突: 无

| [1] | Hogeveen M, Blom HJ, den Heijer M. Maternal homocysteine and small-for-gestational-age offspring:systematic review and Meta-analysis[J]. Am J Clin Nutr, 2012, 95(1): 130–136. DOI:10.3945/ajcn.111.016212 |

| [2] | Levy-Marchal C, Jaquet D. Long-term metabolic consequences of being born small for gestational age[J]. PediatrDiabetes, 2004, 5(3): 147–153. DOI:10.1111/j.1399-543X.2004.00057.x |

| [3] | Boguszewski MC, Mericq V, Bergada I, et al. Latin American consensus:children born small for gestational age[J]. BMC Pediatr, 2011, 11(1): 66. DOI:10.1186/1471-2431-11-66 |

| [4] | Tinker SC, Cogswell ME, Devine O, et al. Folic acid intake among U.S. women aged 15-44 years, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2003-2006[J]. Am J Prev Med, 2010, 38(5): 534–542. DOI:10.1016/j.amepre.2010.01.025 |

| [5] |

严双琴, 徐叶清, 苏普玉, 等.

围孕期增补叶酸与不良出生结局的队列研究[J]. 中华流行病学杂志, 2013, 34(1): 1–4.

Yan SQ, Xu YQ, Su PY, et al. Relationship between folic acid supplements during peri-conceptional period and the adverse pregnancy outcomes:a cohort study[J]. Chin J Epidemiol, 2013, 34(1): 1–4. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2013.01.001 |

| [6] |

徐蓉, 郝加虎, 陶芳标, 等.

10407名单胎活产儿SGA发生率及其影响因素的队列研究[J]. 中国妇幼保健, 2012, 27(4): 560–565.

Xu R, Hao JH, Tao FB, et al. Cohort study on the incidence and effect factors of small for gestational age among 10407 infants with single fetus and live birth[J]. Mater Child Health Care China, 2012, 27(4): 560–565. |

| [7] | Liu YY, Dai W, Dai XQ, et al. Prepregnancy body mass index and gestational weight gain with the outcome of pregnancy:a 13-year study of 292568 cases in China[J]. Arch Gynecol Obstet, 2012, 286(4): 905–911. DOI:10.1007/s00404-012-2403-6 |

| [8] |

宫相君, 郝加虎, 陶芳标, 等.

孕妇增补微量营养素状况及其与妊娠结局关联的队列研究[J]. 中国妇幼保健, 2012, 27(22): 3395–3401.

Gong XJ, Hao JH, Tao FB, et al. Cohort study of the status of trace elements supplement and its relationship with pregnancy outcome[J]. Mater Child Health Care China, 2012, 27(22): 3395–3401. |

| [9] | Catov JM, Bodnar LM, Ness RB, et al. Association of periconceptional multivitamin use and risk of preterm or small-for-gestational-age births[J]. Am J Epidemiol, 2007, 166(3): 296–303. DOI:10.1093/aje/kwm071 |

| [10] | Martinussen MP, Bracken MB, Triche EW, et al. Folic acid supplementation in early pregnancy and the risk ofpreeclampsia, small for gestational age offspring and pretermdelivery[J]. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol, 2015, 195: 94–99. DOI:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2015.09.022 |

| [11] |

张宝林, 冯泽康, 张丽辉.

中国15个城市不同胎龄新生儿体格发育调查研究[J]. 中华儿科杂志, 1988, 26(4): 206–208.

Zhang BL, Feng ZK, Zhang LH. Investigation of the neonatal birth weight for gestational age and percentile in 15 cities in China[J]. Chin J Pediatr, 1988, 26(4): 206–208. |

| [12] |

中国肥胖问题工作组数据汇总分析协作组.

我国成人体重指数和腰围对相关疾病危险因素异常的预测价值:适宜体重指数和腰围切点的研究[J]. 中华流行病学杂志, 2002, 23(1): 5–10.

Coorperative Meta-analysis Group of China Obesity Task Force. Predictive values of body mass index and waist circumference to risk factors of related diseases in Chinese adult population[J]. Chin J Epidemiol, 2002, 23(1): 5–10. DOI:10.3760/j.issn.0254-6450.2002.01.003 |

| [13] | Furness DLF, Yasin N, Dekker GA, et al. Maternal red blood cell folate concentration at 10-12 weeks gestation and pregnancy outcome[J]. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med, 2012, 25(8): 1423–1427. DOI:10.3109/14767058.2011.636463 |

| [14] | Timmermans S, Jaddoe VWV, Hofman A, et al. Periconception folic acid supplementation, fetal growth and the risks of low birth weight and preterm birth:the Generation R Study[J]. Br J Nutr, 2009, 102(5): 777–785. DOI:10.1017/S0007114509288994 |

| [15] | Mojtabai R. Body mass index and serum folate in childbearing age women[J]. Eur J Epidemiol, 2004, 19(11): 1029–1036. DOI:10.1007/s10654-004-2253-z |

| [16] | Mahabir S, Ettinger S, Johnson L, et al. Measures of adiposity and body fat distribution in relation to serum folate levels in postmenopausal women in a feeding study[J]. Eur J Clin Nutr, 2008, 62(5): 644–650. DOI:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602771 |

| [17] | Butterworth CE Jr, Hatch KD, Macaluso M, et al. Folate deficiency and cervical dysplasia[J]. JAMA, 1992, 267(4): 528–533. DOI:10.1001/jama.1992.03480040076034 |

| [18] | Hodgetts VA, Morris RK, Francis A, et al. Effectiveness of folic acid supplementation in pregnancy on reducing the risk of small-for-gestational age neonates:a population study, systematic review and Meta-analysis[J]. BJOG, 2015, 122(4): 478–490. DOI:10.1111/1471-0528.13202 |

| [19] | Wang M, Wang ZP, Gao LJ, et al. Maternal body mass index and the association between folic acid supplements and neural tube defects[J]. Acta Paediatr, 2013, 102(9): 908–913. DOI:10.1111/apa.12313 |

2017, Vol. 38

2017, Vol. 38