文章信息

- 尤优, 严双琴, 黄锟, 毛雷婧, 周珊珊, 葛星, 郝加虎, 朱鹏, 陶芳标.

- You You, Yan Shuangqin, Huang Kun, Mao Leijing, Zhou Shanshan, Ge Xing, Hao Jiahu, Zhu Peng, Tao Fangbiao.

- 妊娠意愿与孕中晚期妊娠相关焦虑关联的队列研究

- Pregnancy intention and pregnancy-related anxiety in the second and third trimester:a birth cohort study

- 中华流行病学杂志, 2017, 38(9): 1179-1182

- Chinese journal of Epidemiology, 2017, 38(9): 1179-1182

- http://dx.doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2017.09.007

-

文章历史

收稿日期: 2017-01-17

2. 243000 安徽省马鞍山市妇幼保健院

2. Maternal and Child Health Care Center of Ma'anshan, Ma'anshan 243000, China

妊娠意愿从不同方面影响着孕妇、家庭乃至社会[1]。研究发现妊娠意愿对产妇孕期、产期和哺乳期的心理健康状态均有显著影响,尤其对孕期情绪,妊娠意愿是重要的影响因素[2]。流行病学调查数据显示,孕妇患焦虑的发生率已达10%~20% [3]。包括一般性焦虑、状态焦虑、特质焦虑及妊娠相关焦虑等[4],其中妊娠相关焦虑是孕期独特的焦虑症状,其定义为妊娠而产生的各种具体的担忧或担心,如对胎儿健康的担心,对分娩和镇痛的担心,对自身健康或体型的担心,对家庭结构变化的担心,对社会功能降低的担心等[5]。我国鲜有妊娠意愿对妊娠相关焦虑的研究,为此本文基于马鞍山优生优育队列(Ma’ anshan-Anhui Birth Cohort,MABC),探讨妊娠意愿与孕中、晚期妊娠相关焦虑的关联。

对象与方法1.研究对象:选取2013年5月至2014年9月在马鞍山市妇幼保健院建立围产保健手册并在该院定期产检及分娩的孕妇作为研究对象,纳入标准见参考文献[6]。本次分析的排除标准为无孕中、晚期有效问卷者。队列共纳入3 474人,其中孕中、晚期失访、胚胎停止发育以及问卷调查缺失等原因分别缺失282人和109人,最终纳入分析样本为3 083人。所有研究对象均签署书面知情同意。

2.研究方法:孕妇在建立围产保健手册时,首次产检并填写《孕早期母婴健康记录表》,收集一般人口学特征、妊娠史、妊娠意愿、配偶情况等信息,并由接受过培训的研究人员测量体重和身高。其中妊娠意愿是指孕妇的受孕意愿。通过回答问题“您此次是在什么情况下怀孕的”将妊娠意愿分为3类,即① 有充分思想准备怀孕(想怀孕,准备怀孕);② 顺其自然(没准备怀孕,但也不排斥怀孕);③ 意外妊娠(暂时不计划怀孕或不想怀孕)。在孕中期(孕24~28周)及孕晚期(孕32~34周)分别填写自编的《妊娠相关焦虑量表》,该量表信度较好,Cronbach’s α系数为0.82[7]。该量表孕中、晚期的Cronbach’s α系数分别为0.83、0.84,具有较好的一致性。量表由13个与妊娠相关条目组成,分为3个维度,即“关注自我”、“担心胎儿健康”、“害怕分娩”。量表采用4级评分:① 没有担心;② 偶尔担心;③ 经常担心;④ 一直担心;分别计为1、2、3、4分,将13个条目的得分相加得出总分,以总分P75所对应的得分作为划分妊娠相关焦虑的标准[8]。

3.统计学分析:采用EpiData 3.0和SPSS 20.0软件录入和分析数据。各组间基线资料的分布差异采用χ2检验。将有统计学意义的变量作为控制变量,采用二分类logistic回归进行多因素分析探究妊娠意愿与孕中、晚期妊娠相关焦虑的关联。以P<0. 05为差异有统计学意义。

结果1.一般特征:3 083名孕妇中年龄≤24岁组占35.9%,25~岁组占48.8%,≥30岁组占15.3%;城市人口占60.6%;文化程度为小学或初中占16.5%,高中或中专占22.3%,大专占31.4%,本科及以上占26.5%;独生子女占33.8%;家庭人均月收入<1 000元者占1.6%,2 500~4 000元占43.3%,>4 000元占30.6%;其配偶吸烟占46.7%;饮酒占61.3%;初产妇占55.8%。意外妊娠报告率为15.0%(461/3 083)。妊娠意愿在年龄、户口所在地、文化程度、家庭人均月收入、配偶吸烟状况以及产次上的差异有统计学意义(表 1)。

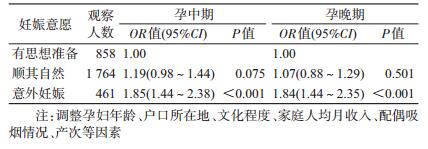

2.妊娠意愿与孕中、晚期妊娠相关焦虑的关联:采用多因素logistic回归分析在控制年龄、户口所在地、文化程度、家庭人均月收入、配偶吸烟情况、产次等混杂因素后,与有思想准备的孕妇相比,意外妊娠的孕妇孕中期出现妊娠相关焦虑的风险增加(OR=1.85,95%CI:1.44~2.38);孕晚期出现妊娠相关焦虑的风险也增加(OR=1.84,95%CI:1.44~2.35);顺其自然怀孕的孕妇在孕中、晚期未增加妊娠相关焦虑发生风险(表 2)。

本研究孕中期妊娠相关焦虑检出率为29.13%,孕晚期妊娠相关焦虑的检出率为30.36%。结果接近于Arch[9]横断面调查妊娠相关焦虑发生率(29.32%)。多项研究表明,妊娠相关焦虑比一般性焦虑、状态焦虑更能对孕妇、妊娠结局及子代的发育产生深远影响,如自发性早产[10]、婴儿低出生体重[11]、产后抑郁[12]以及影响子代心理健康[13]、行为发育[14]等。

本研究比较妊娠意愿对孕中、晚期妊娠相关焦虑的影响,其中意外妊娠的发生率为15.00%,结果发现与有思想准备孕妇相比,意外妊娠能增加孕中、晚期妊娠相关焦虑的发生风险,而顺其自然怀孕与孕中、晚期妊娠相关焦虑间的关联并无统计学意义。

国内外多采用一般性焦虑量表、状态-特征焦虑量表或爱丁堡产后抑郁量表评定孕期焦虑,结果显示非意愿妊娠孕妇更容易出现孕期焦虑或抑郁[15-18];但目前采用妊娠相关焦虑量表对孕期特有焦虑症状进行评定的研究较少。妊娠相关焦虑作为孕期独特的焦虑症状,能够更确切的探究孕期妇女的恐惧和担心,因此更具有代表性。而一般性焦虑量表或抑郁量表等只能解释很小一部分孕期恐惧[19]。Schetter等[20]对5 271名孕妇进行前瞻性队列研究,在孕中期(24~26周)采用妊娠相关焦虑量表评定,发现非意愿妊娠孕妇在孕中期有较高的妊娠相关焦虑。Arch[9]对美国311名孕妇进行横断面调查发现,非意愿妊娠孕妇中,不想怀孕的孕妇在整个孕期会出现妊娠相关焦虑,而暂时不计划怀孕的孕妇在孕期并未出现妊娠相关焦虑。本文证实了先前的研究结果。

本研究基于前瞻性出生队列研究,明确妊娠意愿对孕中、晚期妊娠相关焦虑的影响。但有关妊娠意愿分类,国内外大多数研究将妊娠意愿分为意愿妊娠和非意愿妊娠两类,也有部分研究进一步将非意愿妊娠分为不想怀孕和暂时不计划怀孕。有研究发现仅按上述标准划分两类忽略了部分未准备怀孕但也不排斥怀孕的孕妇[21]。因此本研究考虑了介于意愿妊娠和非意愿妊娠之间部分顺其自然怀孕的孕妇,将妊娠意愿分为意外妊娠、顺其自然和有思想准备3类。本文为队列研究,避免了回忆偏倚。

本文存在局限。流行病学研究发现,每年约有5 000万非意愿妊娠孕妇选择流产[22],本队列是在排除了部分因意外妊娠而选择流产的孕妇,因此可能低估了意外妊娠的发生率;研究中未考虑孕期不良生活事件或压力等可能对妊娠相关焦虑产生影响,结果可能存在偏倚;此外研究对象均来自同一医院,有局限性,影响了研究结果的外推。

总之,本研究认为意外妊娠能增加妊娠相关焦虑的发生率,妊娠意愿对孕妇的心理健康有重要的影响。

利益冲突: 无

| [1] | Moosazadeh M, Nekoei-Moghadam M, Emrani Z, et al. Prevalence of unwanted pregnancy in Iran:a systematic review and Meta-analysis[J]. Int J Health Plann Manage, 2014, 29(3): e277–290. DOI:10.1002/hpm.2184 |

| [2] |

王小丽, 董燕, 任东平, 等.

非意愿妊娠对孕妇不同孕期情绪状态的影响[J]. 中国健康心理学杂志, 2013, 21(5): 678–680.

Wang XL, Dong Y, Ren DP, et al. The influences of unintended pregnancy on emotion characteristics during different trimesters[J]. Chin J Health Psychol, 2013, 21(5): 678–680. DOI:10.13342/j.cnki.cjhp.2013.05.043 |

| [3] | Ali NS, Azam IS, Ali BS, et al. Frequency and associated factors for anxiety and depression in pregnant women:a hospital-based cross-sectional study[J]. Sci World J, 2012, 2012: 653098. DOI:10.1100/2012/653098 |

| [4] | Brunton RJ, Dryer R, Saliba A, et al. Pregnancy anxiety:a systematic review of current scales[J]. J Affect Disord, 2015, 176: 24–34. DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2015.01.039 |

| [5] | Mulder EJH, de Medina PGR, Huizink AC, et al. Prenatal maternal stress:effects on pregnancy and the (unborn) child[J]. Early Hum Dev, 2002, 70(1/2): 3–14. DOI:10.1016/S0378-3782(02)00075-0 |

| [6] |

葛星, 徐叶清, 黄三唤, 等.

妊娠期肝内胆汁淤积症对分娩结局影响的出生队列研究[J]. 中华流行病学杂志, 2016, 37(2): 187–191.

Ge X, Xu YQ, Huang SH, et al. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy and fetal outcomes:a prospective birth cohort study[J]. Chin J Epidemiol, 2016, 37(2): 187–191. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2016.02.007 |

| [7] |

肖利敏, 陶芳标, 章景丽, 等.

妊娠相关焦虑量表编制及信度评价[J]. 中国公共卫生, 2012, 28(3): 275–277.

Xiao LM, Tao FB, Zhang JL, et al. Development and reliability evaluation of a pregnancy-related anxiety questionnaire[J]. Chin J Public Health, 2012, 28(3): 275–277. DOI:10.11847/zgggws2012-28-03-08 |

| [8] |

曹慧, 严双琴, 丁昌芝, 等.

孕早期牙龈出血与妊娠相关焦虑症状关系[J]. 中国公共卫生, 2013, 29(7): 953–956.

Cao H, Yan SQ, Ding CZ, et al. Relationship between gum bleeding in first trimester of pregnancy and pregnancy-related anxiety[J]. Chin J Public Health, 2013, 29(7): 953–956. DOI:10.11847/zgggws2013-29-07-05 |

| [9] | Arch JJ. Pregnancy-specific anxiety:which women are highest and what are the alcohol-related risks?[J]. Compr Psychiatry, 2013, 54(3): 217–228. DOI:10.1016/j.comppsych.2012.07.010 |

| [10] | Kramer MS, Lydon J, Séguin L, et al. Stress pathways to spontaneous preterm birth:the role of stressors, psychological distress, and stress hormones[J]. Am J Epidemiol, 2009, 169(11): 1319–1326. DOI:10.1093/aje/kwp061 |

| [11] |

章景丽. 妊娠相关焦虑与不良妊娠结局关联的队列研究[D]. 合肥: 安徽医科大学, 2011.

Zhang JL. Pregnancy-related anxiety and adverse pregnancy outcomes:a population-based cohort study[D]. Hefei:Anhui Medical University, 2011. http://cdmd.cnki.com.cn/Article/CDMD-10366-1011162603.htm |

| [12] | Milgrom J, Gemmill AW, Bilszta JL, et al. Antenatal risk factors for postnatal depression:a large prospective study[J]. J Affect Disord, 2008, 108(1/2): 147–157. DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2007.10.014 |

| [13] | Buss C, Davis EP, Hobel CJ, et al. Maternal pregnancy-specific anxiety is associated with child executive function at 6-9 years age[J]. Stress, 2011, 14(6): 665–676. DOI:10.3109/10253890.2011.623250 |

| [14] | Nolvi S, Karlsson L, Bridgett DJ, et al. Maternal prenatal stress and infant emotional reactivity six months postpartum[J]. J Affect Disord, 2016, 199: 163–170. DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2016.04.020 |

| [15] | Bunevicius R, Kusminskas L, Bunevicius A, et al. Psychosocial risk factors for depression during pregnancy[J]. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand, 2009, 88(5): 599–605. DOI:10.1080/00016340902846049 |

| [16] | Karmaliani R, Asad N, Bann CM, et al. Prevalence of anxiety, depression and associated factors among pregnant women of Hyderabad, Pakistan[J]. Int J Soc Psychiatry, 2009, 55(5): 414–424. DOI:10.1177/0020764008094645 |

| [17] | Maxson P, Miranda ML. Pregnancy intention, demographic differences, and psychosocial health[J]. J Womens Health (Larchmt), 2011, 20(8): 1215–1223. DOI:10.1089/jwh.2010.2379 |

| [18] | Dagklis T, Papazisis G, Tsakiridis I, et al. Prevalence of antenatal depression and associated factors among pregnant women hospitalized in a high-risk pregnancy unit in Greece[J]. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol, 2016, 51(7): 1025–1031. DOI:10.1007/s00127-016-1230-7 |

| [19] | Huizink AC, Mulder EJH, de Medina PGR, et al. Is pregnancy anxiety a distinctive syndrome?[J]. Early Hum Dev, 2004, 79(2): 81–91. DOI:10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2004.04.014 |

| [20] | Schetter CD, Niles AN, Guardino CM, et al. Demographic, medical, and psychosocial predictors of pregnancy anxiety[J]. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol, 2016, 30(5): 421–429. DOI:10.1111/ppe.12300 |

| [21] | Kavanaugh ML, Schwarz EB. Prospective assessment of pregnancy intentions using a single-versus a multi-item measure[J]. Perspect Sex Reprod Health, 2009, 41(4): 238–243. DOI:10.1363/4123809 |

| [22] | Akbarzadeh M, Yazdanpanahi Z, Zarshenas L, et al. The women's perceptions about unwanted pregnancy:a qualitative study in Iran[J]. Glob J Health Sci, 2016, 8(5): 189–196. DOI:10.5539/gjhs.v8n5p189 |

2017, Vol. 38

2017, Vol. 38