文章信息

- 李姗姗, 张若, 兰欣, 屈鹏飞, 党少农, 陈方尧, 颜虹.

- Li Shanshan, Zhang Ruo, Lan Xin, Qu Pengfei, Dang Shaonong, Chen Fangyao, Yan Hong.

- 孕期环境空气污染物暴露和先天性心脏病关系的Meta分析

- Prenatal exposure to ambient air pollution and congenital heart disease:a Meta-analysis

- 中华流行病学杂志, 2017, 38(8): 1121-1126

- Chinese journal of Epidemiology, 2017, 38(8): 1121-1126

- http://dx.doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2017.08.025

-

文章历史

收稿日期: 2016-12-05

目前我国出生缺陷总发生率约为5.6%,严重影响儿童的生命和生活质量,给家庭和社会带来了沉重的精神和经济负担[1]。先天性心脏病(先心病),是指在胚胎发育的过程中出现了心脏、血管结构和功能上的异常[2]。近10年来,先心病发生率呈上升趋势,始终位居出生缺陷监测的首位[3]。先心病主要包括室间隔缺损(ventricular septal defect,VSD)、房间隔缺损(atrial septal defect,ASD)、动脉导管未闭(patent ductus arteriosus,PDA)、法洛四联症(tetralogy of fallot,TOF)、主动脉缩窄(coarctation of aorta,COA)、肺动脉狭窄(pulmonary artery stenosis,PAS)和肺动脉瓣狭窄(pulmonary valve stenosis,PVS),其中以VSD最为常见[4]。先心病病因未明,普遍认为是环境因素和遗传因素相互作用的结果[5]。近年来随着空气污染日益严重,越来越多的学者开始研究空气污染物与疾病之间的关系,但目前有关先心病的结论尚存在争论。为此,我们拟对国内外发表的有关孕期空气污染暴露和先心病关系的研究文章进行Meta分析,以期为先心病的一级预防提供参考依据。

资料与方法1.文献检索策略:在PubMed、Web of Science和Google Scholar等英文数据库和中国知网、万方数据知识服务平台、维普期刊资源整合服务平台等中文数据库检索2000年1月1日至2016年11月30日发表的相关文献。中文数据库检索词为“出生缺陷”、“先天性心脏病”、“空气污染”、“环境污染”、“孕期”、“大气颗粒物或PM2.5或PM10”、“二氧化硫或SO2”、“二氧化氮或NO2”、“一氧化碳或CO”、“臭氧或O3”;英文数据库检索词为“congenital abnormalities”、“birth defect”、“cardiac anomalies”、“congenital heart disease”、“air pollution”、“nitrogen dioxide or NO2”、“atmospheric particulate or PM2.5 or PM10”、“sulfur dioxide or SO2”、“carbon monoxide or CO”、“ozone or O3”。同时通过手工检索和文献追溯获取更多的相关文献。

2.纳入与排除标准:纳入标准:① 为孕期室外空气污染物暴露对先心病影响的研究;② 研究类型为病例对照或队列研究;③ 污染物和先心病有明确分类;④ 中文或英文。排除标准:① 综述或病例报告类文献;② 污染物无明确测量数据(比如污染区或非污染区);③ 无法获取效应量及其可信区间。

3.数据提取:资料提取内容主要包括第一作者、发表年份、研究地点和时间、样本量、病例和对照选取标准、空气污染物和先心病种类、暴露时间、暴露评估方法、统计分析方法以及模型中控制的混杂因素等。由于不同文献研究的污染物暴露时期不同,我们提取最接近心脏发育的时期(孕3~8周)的效应值[6]。同时根据研究中污染物数据的类型,从两个方面来进行分析:① 高浓度对比低浓度的污染物与先心病关系的Meta分析(由于部分文献仅提供污染物每升高一个单位先心病发生的危险度,使用报道中提供的四分位数间距,把连续性数据计算所得的危险度转换为污染物每增加一个四分位数间距先心病的危险度);② 连续性变化的污染物与先心病关系的Meta分析(为了保证数据的可比性,不同研究中污染物的单位将进行统一转换:PM10和PM2.5单位为10 μg/m3;O3和NO2单位为10 mm3/m3;SO2单位为1 mm3/m3;CO单位为1 cm3/m3)。采用Newcastle Ottawa Scale评分标准[7]对纳入的文献进行方法学质量评价。

4.统计学分析:采用Stata 12.0软件对数据进行Meta分析,采用I2统计量衡量各研究结果间的异质性大小,如果各研究间不存在异质性(I2≤40%和P>0.10),采用固定效应模型计算合并OR值及其95%CI;如果存在异质性,采用随机效应模型。采用敏感性分析评价Meta分析结论的稳定性,判断剔除队列研究、未控制混杂因素、污染物暴露时期非孕早期、使用模型估计污染物暴露水平、病例样本量<100等研究前后合并效应值的差异。采用Egger线性回归法对发表偏倚进行定量分析,检验水准取双侧α=0.05。

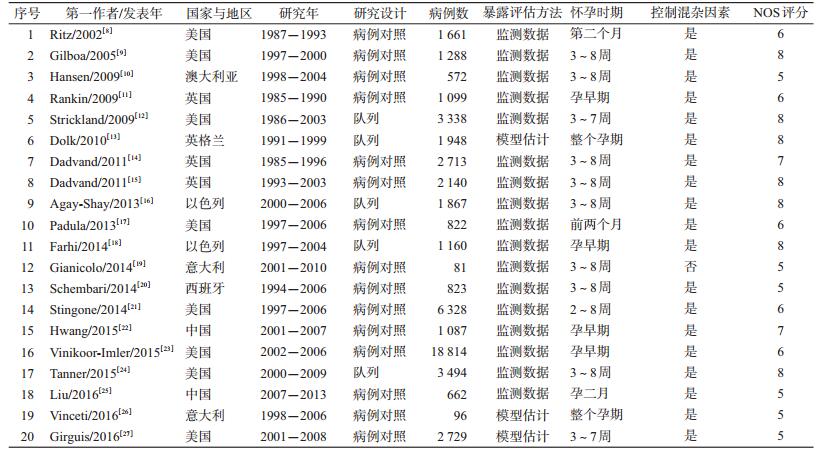

结果1.纳入文献概况:共检索出相关文献1 936篇,剔除与研究目的无关,综述和病例报告类文献,无明确先心病分类、无法获得效应值和可信区间等,最终纳入20篇文献(其中Dadvand在2011年发表的2篇关于污染物与先心病关系的文章,因研究的时期,污染物种类和水平不完全相同,作2项独立研究处理),全部为英文。研究地区包括美国(8篇)、英国(4篇)、意大利(2篇)、以色列(2篇)、澳大利亚(1篇)、西班牙(1篇)、中国(2篇)。其中,病例对照研究和队列研究各15篇和5篇。大部分研究仅使用污染物监测数据来评估污染物暴露水平,有3项研究结合气象数据、道路汽车流量、土地使用等数据建立统计模型来估计污染物暴露情况。按NOS标准对20项研究进行质量评价,得分范围为5~8分。见表 1。

2. Meta分析:

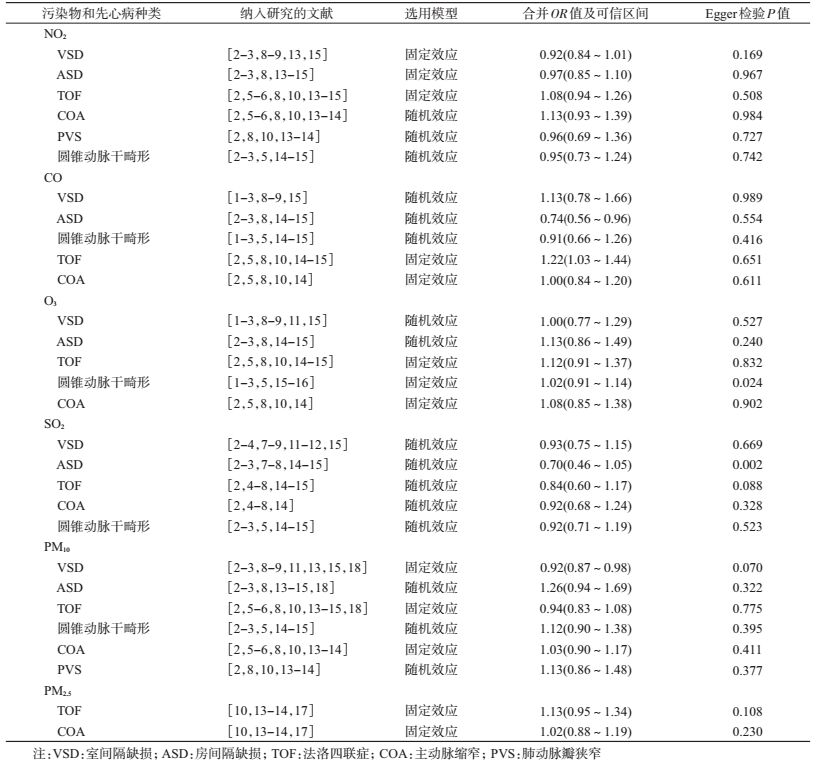

(1) 污染物高浓度比低浓度时,与先心病关系的Meta分析:当污染物的数据类型是等级变量时,对先心病的8个亚型和6种污染物的关系分别进行Meta分析,除PM2.5与先心病的组合只包括4篇文献,其余污染物与先心病的组合至少包括5篇文献。根据异质性检验结果选择固定效应或随机效应模型,结果显示,CO对ASD的影响差异有统计学意义(P<0.05),其合并OR值为0.74 (95%CI:0.56~0.96),CO对TOF的影响差异有统计学意义(P<0.05),其合并OR值为1.22 (95%CI:1.03~1.44),PM10对VSD的影响差异有统计学意义(P<0.05),其合并OR值为0.92 (95%CI:0.87~0.98)。见表 2。

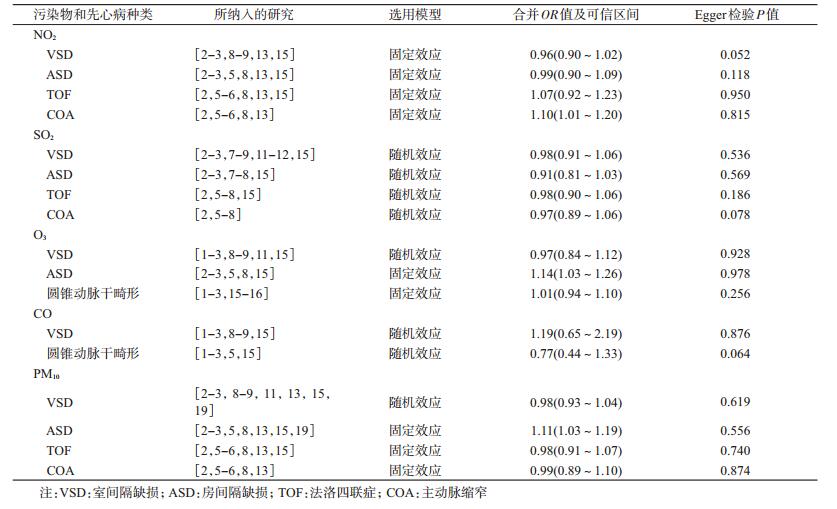

(2) 污染物连续性变化时,与先心病关系的Meta分析:当污染物的数据类型是连续性变量时,对先心病的5个亚型和5种污染物的关系分别进行Meta分析,每个组合至少包括5篇文献。根据异质性检验结果选择固定效应或随机效应模型,结果显示,NO2对COA的影响差异有统计学意义(P<0.05),其合并OR值为1.10(95%CI:1.01~1.20),O3对ASD的影响差异有统计学意义(P<0.05),其合并OR值为1.14 (95%CI:1.03~1.26),PM10对ASD的影响差异有统计学意义(P<0.05),其合并OR值为1.11 (95%CI:1.03~1.19)。见表 3。

3.敏感性分析:先后移除队列研究[12-13, 16, 18, 24]、暴露时期非孕早期[13, 26]、未控制混杂因素[19]、使用模型估计污染物暴露水平[13, 26-27]、病例数<100[19, 26]的研究后,发现所有组合的合并OR值结果稳定。

4.发表偏倚:使用Egger法对发表偏倚进行定量分析,结果显示,当污染物高浓度比低浓度时,O3的暴露和圆锥动脉干畸形的发生、SO2暴露和ASD的发生可能存在发表偏倚(P<0.05),其余各相关研究均不存在发表偏倚(P>0.05)。见表 2,3。

讨论本文Meta分析收集了国内外2000-2016年公开发表的关于大气污染对先心病影响的相关流行病学研究,将包括NO2、SO2、CO、O3、PM10、PM2.5在内的6种污染物对常见先心病亚型的影响效应值分别进行合并。本研究结果进一步证实了孕期大气污染物暴露增加先心病的发生危险,即暴露于高浓度的CO,相比于低浓度,TOF的发生增加1.22倍;空气中NO2的浓度每升高10 mm3/m3,发生COA的危险升高到1.01倍;空气中O3的浓度每升高10 mm3/m3,发生ASD的危险升高到1.14倍;空气中PM10的浓度每升高10 μg/m3,发生ASD的危险升高到1.10倍。此外,本研究还发现CO暴露和ASD的发生,PM10暴露和VSD的发生存在负相关。

由于PM2.5相关研究数量较少,本文Meta分析并未发现孕期PM2.5暴露与先心病发生的相关性。但细颗粒物PM2.5因其颗粒直径较小、表面积较大,与粗颗粒物相比,更容易富集有毒物质,对人体健康的危害更大[28]。国内外对PM2.5与不良妊娠结局关系的研究尚处于起步阶段,提示未来应加快该领域的流行病学研究。本研究发现,孕期CO、PM10暴露和某些先心病亚型的发生呈负相关。多个流行病学研究对污染物暴露与先心病发生的负相关均有报道[9-10, 15-16, 20, 22],分析可能是由于研究方法学限制或者分析模型中未对某些关键混杂因素进行控制,也有可能是因为孕期污染物暴露导致孕早期胎儿流产,从而减少了出生缺陷的发生[29]。

目前已有动物实验证明,孕期暴露于空气污染物O3、NO2、CO对胎儿具有致畸作用[30-33]。空气污染物致畸作用的机制可能包括:触发机体氧化应激反应,进而影响神经嵴细胞的迁移和分化;导致组织缺氧;影响机体新陈代谢和对有害异物的解毒作用;影响体细胞DNA的效应,例如,干扰程序化凋亡(死亡)等基本过程;影响滋养层细胞的功能和早期胎儿生长发育等[14]。

本次Meta分析结果存在局限性。由于各研究地区污染物暴露水平高低不同,且污染物的评估方法和控制的混杂因素不一致,导致纳入分析的文献存在异质性。同时,检索文献语种的限制可能产生偏倚。此外,本研究结果虽表明孕期空气污染物暴露与先心病的发生相关,但影响强度较小,可提供的证据有限。

综上所述,孕期暴露于CO、O3、NO2、PM10可能会增加先心病的风险,提示孕期,尤其是胎儿心脏发育的关键时期(孕3~8周),孕妇应尽量避免暴露于空气污染严重的环境中。

利益冲突: 无

| [1] |

中华人民共和国卫生部. 中国出生缺陷防治报告(2012)[R]. 北京: 中华人民共和国卫生部, 2012.

Ministry of Health of the People's Republic of China. Report on prevention and treatment of birth defects in China[R]. Beijing:Ministry of Health of the People's Republic of China, 2012. |

| [2] |

申昆玲.儿科学[M]. 2版. 北京: 北京大学医学出版社, 2009.

Shen KL.Pediatrics[M]. 2nd ed. Beijing: Peking University Medical Press, 2009. |

| [3] |

郝建珍, 陈燕杰, 耿红, 等.

北京市东城区1995-2014年出生缺陷分析[J]. 中国公共卫生, 2016, 32(4): 547–550.

Hao JZ, Chen YJ, Geng H, et al. Birth defects in Dongcheng district of Beijing, 1995-2014[J]. Chin J Public Health, 2016, 32(4): 547–550. DOI:10.11847/zgggws2016-32-04-36 |

| [4] |

施淼, 洪新如, 孙庆华.

先天性心脏病病因学的研究进展[J]. 国际妇产科学杂志, 2012, 39(2): 183–186.

Shi M, Hong XR, Sun QH. Progress on etiology research of congenital heart disease[J]. J Int Obetet Gynecol, 2012, 39(2): 183–186. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1674-1870.2012.02.019 |

| [5] |

高燕, 黄国英.

先天性心脏病病因及流行病学研究进展[J]. 中国循证儿科杂志, 2008, 3(3): 213–222.

Gao Y, Huang GY. Advance in the Etiology and the epidemiology of congenital heart disease[J]. Chin J Evid Based Pediatr, 2008, 3(3): 213–222. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1673-5501.2008.03.009 |

| [6] | Vrijheid M, Martinez D, Manzanares S, et al. Ambient air pollution and risk of congenital anomalies:a systematic review and Meta-analysis[J]. Environ Health Perspect, 2011, 119(5): 598–606. DOI:10.1289/ehp.1002946 |

| [7] | Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in Meta-analyses[EB/OL]. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. |

| [8] | Ritz B, Yu F, Fruin S, et al. Ambient air pollution and risk of birth defects in Southern California[J]. Am J Epidemiol, 2002, 155(1): 17–25. DOI:10.1093/aje/155.1.17 |

| [9] | Gilboa SM, Mendola P, Olshan AF, et al. Relation between ambient air quality and selected birth defects, seven county study, Texas, 1997-2000[J]. Am J Epidemiol, 2005, 162(3): 238–252. DOI:10.1093/aje/kwi189 |

| [10] | Hansen CA, Barnett AG, Jalaludin BB, et al. Ambient air pollution and birth defects in brisbane, australia[J]. PLoS One, 2009, 4(4): e5408. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0005408 |

| [11] | Rankin J, Chadwick T, Natarajan M, et al. Maternal exposure to ambient air pollutants and risk of congenital anomalies[J]. Environ Res, 2009, 109(2): 181–187. DOI:10.1016/j.envres.2008.11.007 |

| [12] | Strickland MJ, Klein M, Correa A, et al. Ambient air pollution and cardiovascular malformations in Atlanta, Georgia, 1986-2003[J]. Am J Epidemiol, 2009, 169(8): 1004–1014. DOI:10.1093/aje/kwp011 |

| [13] | Dolk H, Armstrong B, Lachowycz K, et al. Ambient air pollution and risk of congenital anomalies in England, 1991-1999[J]. Occup Environ Med, 2010, 67(4): 223–227. DOI:10.1136/oem.2009.045997 |

| [14] | Dadvand P, Rankin J, Rushton S, et al. Association between maternal exposure to ambient air pollution and congenital heart disease:a register-based spatiotemporal analysis[J]. Am J Epidemiol, 2011, 173(2): 171–182. DOI:10.1093/aje/kwq342 |

| [15] | Dadvand P, Rankin J, Rushton S, et al. Ambient air pollution and congenital heart disease:a register-based study[J]. Environ Res, 2011, 111(3): 435–441. DOI:10.1016/j.envres.2011.01.022 |

| [16] | Agay-Shay K, Friger M, Linn S, et al. Air pollution and congenital heart defects[J]. Environ Res, 2013, 124: 28–34. DOI:10.1016/j.envres.2013.03.005 |

| [17] | Padula AM, Tager IB, Carmichael SL, et al. Ambient air pollution and traffic exposures and congenital heart defects in the San Joaquin Valley of California[J]. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol, 2013, 27(4): 329–339. DOI:10.1111/ppe.12055 |

| [18] | Farhi A, Boyko V, Almagor J, et al. The possible association between exposure to air pollution and the risk for congenital malformations[J]. Environ Res, 2014, 135: 173–180. DOI:10.1016/j.envres.2014.08.024 |

| [19] | Gianicolo EAL, Mangia C, Cervino M, et al. Congenital anomalies among live births in a high environmental risk area-a case-control study in Brindisi (southern Italy)[J]. Environ Res, 2014, 128: 9–14. DOI:10.1016/j.envres.2013.11.002 |

| [20] | Schembari A, Nieuwenhuijsen MJ, Salvador J, et al. Traffic-related air pollution and congenital anomalies in Barcelona[J]. Environ Health Perspect, 2014, 122(3): 317–323. DOI:10.1289/ehp.1306802 |

| [21] | Stingone JA, Luben TJ, Daniels JL, et al. Maternal exposure to criteria air pollutants and congenital heart defects in offspring:results from the national birth defects prevention study[J]. Environ Health Perspect, 2014, 122(8): 863–872. DOI:10.1289/ehp.1307289 |

| [22] | Hwang BF, Lee YL, Jaakkola JJK. Air pollution and the risk of cardiac defects:a population-based case-control study[J]. Medicine (Baltimore), 2015, 94(44): e1883. DOI:10.1097/md.zhlxbxzz-38-8-112101883 |

| [23] | Vinikoor-Imler LC, Stewart TG, Luben TJ, et al. An exploratory analysis of the relationship between ambient ozone and particulate matter concentrations during early pregnancy and selected birth defects in Texas[J]. Environ Pollut, 2015, 202: 1–6. DOI:10.1016/j.envpol.2015.03.001 |

| [24] | Tanner JP, Salemi JL, Stuart AL, et al. Associations between exposure to ambient benzene and PM2.5 during pregnancy and the risk of selected birth defects in offspring[J]. Environ Res, 2015, 142: 345–353. DOI:10.1016/j.envres.2015.07.006 |

| [25] | Liu CB, Hong XR, Shi M, et al. Effects of prenatal PM10 exposure on fetal cardiovascular malformations in Fuzhou, China:a retrospective case-control study[J]. Environ Health Perspect, 2016. DOI:10.1289/EHP289 |

| [26] | Vinceti M, Malagoli C, Malavolti M, et al. Does maternal exposure to benzene and PM10 during pregnancy increase the risk of congenital anomalies?A population-based case-control study[J]. Sci Total Environ, 2016, 541: 444–450. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.09.051 |

| [27] | Girguis MS, Strickland MJ, Hu XF, et al. Maternal exposure to traffic-related air pollution and birth defects in Massachusetts[J]. Environ Res, 2016, 146: 1–9. DOI:10.1016/j.envres.2015.12.010 |

| [28] |

杨洪斌, 邹旭东, 汪宏宇, 等.

大气环境中PM2.5的研究进展与展望[J]. 气象与环境学报, 2012, 28(3): 77–82.

Yang HB, Zou XD, Wang HY, et al. Study progress on PM2.5 in atmospheric environment[J]. J Meteorol Environ, 2012, 28(3): 77–82. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1673-503X.2012.03.014 |

| [29] | Dolk H, Vrijheid M. The impact of environmental pollution on congenital anomalies[J]. Br Med Bull, 2003, 68(1): 25–45. DOI:10.1093/bmb/ldg024 |

| [30] | Longo LD. The biological effects of carbon monoxide on the pregnant woman, fetus, and newborn infant[J]. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 1977, 129(1): 69–103. DOI:10.1016/0002-9378(77)90824-9 |

| [31] | Garvey DJ, Longo LD. Chronic low level maternal carbon monoxide exposure and fetal growth and development[J]. Biol Reprod, 1978, 19(1): 8–14. DOI:10.1095/biolreprod19.1.8 |

| [32] | Kavlock R, Daston G, Grabowski CT. Studies on the developmental toxicity of ozone. I. Prenatal effects[J]. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol, 1979, 48(1): 19–28. DOI:10.1016/S0041-008X(79)80004-6 |

| [33] | Di Giovanni V, Cagiano R, Carratù MR, et al. Alterations in the ontogeny of rat pup ultrasonic vocalization produced by prenatal exposure to nitrogen dioxide[J]. Psychopharmacology, 1994, 116(4): 423–427. DOI:10.1007/BF02247472 |

2017, Vol. 38

2017, Vol. 38