文章信息

- 于慧会, 黄慧瑶, 姜岩松, 朱陈, 郭春光, 代敏, 邢晓静, 石菊芳.

- Yu Huihui, Huang Huiyao, Jiang Yansong, Zhu Chen, Guo Chunguang, Dai Min, Xing Xiaojing, Shi Jufang.

- CT结肠成像技术用于结直肠肿瘤筛查诊断效果的多亚组Meta分析

- Accuracy of CT colonography for the detection of colorectal neoplasm:a subgroup Meta-analysis

- 中华流行病学杂志, 2017, 38(6): 814-820

- Chinese Journal of Epidemiology, 2017, 38(6): 814-820

- http://dx.doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2017.06.025

-

文章历史

收稿日期: 2016-11-01

2. 100021 北京, 国家癌症中心 中国医学科学院北京协和医学院肿瘤医院城市癌症早诊早治项目办公室;

3. 150086 哈尔滨医科大学卫生管理学院卫生经济教研室;

4. 310022 杭州, 浙江省肿瘤医院 浙江省肿瘤防治办公室

2. Program Office for Cancer Screening in Urban China, Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, Peking Union Medical College, Beijing 100021, China;

3. College of Health Management, Harbin Medical University, Harbin 150086, China;

4. Zhejiang Provincial Office for Cancer Prevention, Zhejiang Cancer Center, Zhejiang Cancer Hospital, Hangzhou 310022, China

结直肠肿瘤包括结直肠息肉(腺瘤、幼年性息肉和炎症性息肉)和结直肠癌,其中>85%的结直肠癌是由腺瘤癌变引起,≥10 mm的腺瘤是结直肠癌的癌前病变[1]。结直肠癌疾病负担严重[2-3],早期诊断治疗可以提高结直肠癌患者的生存率,Ⅳ期结直肠癌患者的5年生存率约为10%,而Ⅰ期患者5年生存率>90%[4-5]。证据显示通过筛查发现早期癌/癌前病变,进行有效治疗,可降低结直肠癌死亡率[6]。

目前,广泛用于结直肠肿瘤筛查的技术主要有粪便隐血试验(FOBT)和结直肠镜(CS)检查[7]。FOBT的灵敏度和特异度相对较低,一般作为结直肠肿瘤的初筛技术[8];CS筛查结直肠肿瘤的准确度高且可以直接在镜下进行腺瘤切除,但费用高、存在疼痛及可能出现的出血、穿孔等不良事件,导致依从性低,筛查项目效果不尽如人意[9]。CT结肠成像(computed tomographic colonography,CTC)是指经腹部CT检查获得的数据由计算机处理后构建产生的结肠图像,这些图像模拟光镜检查的效果,是一种微创性检查,对结直肠肿瘤具有较高的准确度[10]。为分析CTC对不同大小肿瘤的诊断效能,以及检查前肠道准备、粪便标记甚至阅片人经验、方式等因素对影响CTC的诊断效能,笔者进行CTC筛查结直肠肿瘤的相关文献荟萃,按肿瘤大小分组(≥6 mm和≥10 mm)对灵敏度、特异度进行Meta分析,并对可能影响CTC诊断效能的因素进行亚组分析,进而为CTC筛查结直肠肿瘤的人群运用提供合理的参考依据。

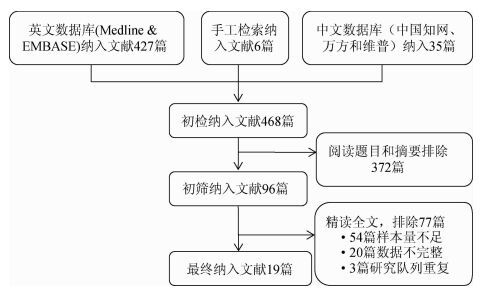

资料与方法1.文献检索:在Medline、Embase英文数据库和中国知网、万方数据知识服务平台、维普期刊资源整合服务平台,检索CTC技术运用于结直肠肿瘤筛查准确度的相关文献,检索日期1994年1月(首次描述CTC)至2016年1月。中文检索以结直肠肿瘤、CT结肠成像、灵敏度和特异度为关键词;英文检索以“colorectal neoplasm”、“colonography,computed tomographic”、“sensitivity and specificity”为主题词,结合相应自由词进行文献检索。此外,手动检索相关系统综述及研究的参考文献作为电子数据库的补充。

2.纳入及排除标准:纳入标准为① 原创性CTC筛查结直肠肿瘤的准确度研究;② 结直肠肿瘤诊断明确(经结肠镜检或病理组织学核实);③ 可获得真阳性、假阳性、假阴性、真阴性的患者数量。排除标准为① 研究对象有既往结直肠癌或癌前病变病史;② 诊断准确度由结直肠病变(如腺瘤)个数计算所得;③ 准确度指标结果为估算值;④ 样本量<200;⑤ 综述或病例报告研究;⑥ 针对同一队列人群研究发表的早期文献。

3.数据提取及质量评价:由2名工作人员背对背按照预先制定的数据表提取数据,若出现不一致时,商议决定。从研究基本特征变量、CTC诊断影响因素及CTC筛查四格表数据3个方面提取数据,具体变量为① 研究基本特征变量包括第一作者、发表年份、研究地区、研究对象特征(普通人群、高危人群和症状人群等)、样本量、年龄;② 影响CTC诊断因素包括是否肠道准备、粪便标记,是否进行双阅片及阅片人的经验(≥100和<100张CT片);③ CTC筛查四格表数据:≥6 mm和≥10 mm结直肠肿瘤的真阳性数、假阳性数、假阴性数和真阴性数。另外,采用QUADAS(Quality of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies)标准进行文献质量评价。该量表为国际通用的系统综述中诊断性研究的质量评价工具,本研究采用的QUADAS 2003年版本[11]。

4.统计学分析:采用Stata 11.0软件进行统计分析。利用综合受试者工作曲线(summary receiver operating characteristic,SROC)曲线下面积(AUC)、灵敏度和特异度描述CTC技术准确度。以双变量混合效应模型(bivariate mixed-effects models)分别对灵敏度及特异度进行合并;通过Q检验的P值以及统计量I2判断纳入研究间的异质性,以I2值为25%、50%、75%作为临界值分成低、中、高3个级别。另外,本研究采用线性回归法进行发表偏倚量化检验。所有统计学检验以P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。

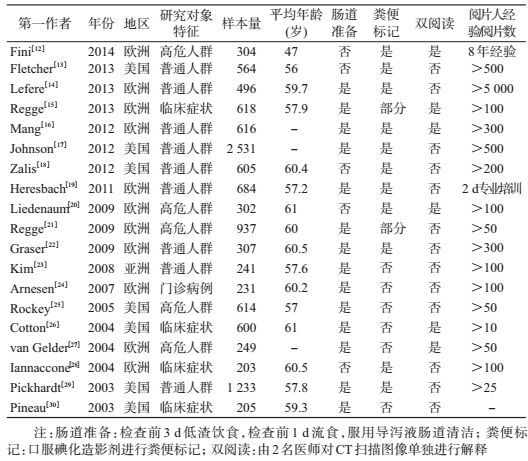

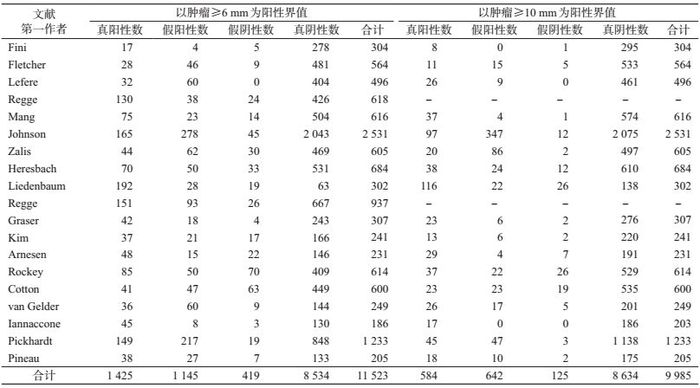

结果1.纳入文献的基本特征:共检索出468篇相关文献(图 1),排除372篇,对初步纳入的96篇文献进行全文精读,再排除77篇,最终纳入19篇文献[12-30],其中11篇(58%)的研究地点是欧洲,7篇(37%)研究地点是美国,1篇研究地点为亚洲。共有14篇(74%)文献描述了肠道准备,进行粪便标记的有13篇(68%),进行双人阅读CT片的文献6篇(32%),要求阅片人的阅片数量>100个图像的文献有12篇(63%)。19篇文献共纳入研究对象11 540人,文献中样本量范围为203~2 531人。9篇(47%)文献研究对象为普通人群进行CTC检查,5篇(26%)文献的研究对象为结直肠癌的高危人群,5篇为有临床症状者。所有文献采用的金标准为非盲法的结肠镜检查(表 1、2)。

|

| 图 1 文献筛选流程图 |

2.文献质量评价:采用的QUADAS共14个条目,覆盖了疾病谱(条目1)、选择标准(条目2)、金标准(条目3)、疾病进展偏倚(条目4)、部分参照偏倚(条目5)、多重参照偏倚(条目6)、混合偏倚(条目7)、待评价试验的实施(条目8)、金标准的实施(条目9)、试验解读偏倚(条目10)、金标准解读偏倚(条目11)、临床解读偏倚(条目12)、难以解释的试验结果(条目13)和退出病例(条目14)。依据QUADAS量表的评价准则,对纳入的19篇文献进行了质量评价,个别文献中存在未完成肠镜而退出的病例,但数量极少,对整体结果的影响甚微。

3.阈值效应检验:对所有≥6 mm结直肠肿瘤研究的灵敏度与特异度进行相关性检验,得到Spearman系数为-0.17,P>0.05,说明灵敏度和特异度是独立的,表明各研究间不存在阈值效应;≥10 mm组的Spearman相关系数为0.33,P>0.05。

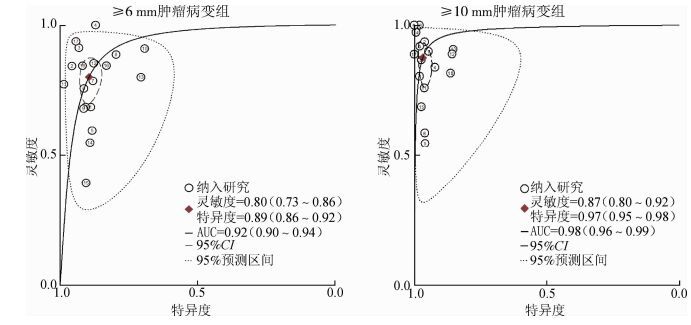

4. SROC曲线分析:观察SROC曲线图(图 2),灵敏度及特异度未呈“肩背状”分布,提示纳入的研究间不存在阈值效应。肿瘤为≥6 mm的灵敏度为0.80,特异度为0.89,AUC=0.92;≥10 mm肿瘤病变的灵敏度是0.87,特异度是0.97,AUC=0.98。

|

| 注:菱形区域为最佳诊断分界点;AUC为受试者工作曲线下面积 图 2 CTC筛查结直肠肿瘤的加权受试者工作曲线 |

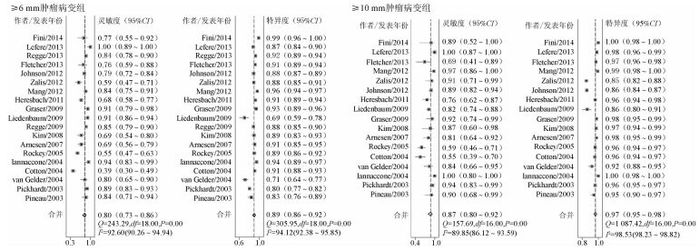

5. Meta分析:采用双变量混合效应模型对总体灵敏度和特异度进行统计推断(图 3)。异质性检验结果提示两组均存在异质性(P<0.05)。≥6 mm肿瘤病变组总体灵敏度为0.80(95%CI:0.73~0.86),总体特异度为0.89(95%CI:0.86~0.92)。≥10 mm肿瘤病变组灵敏度是0.87(95%CI:0.80~0.92)、特异度是0.97(95%CI:0.95~0.98)。

|

| 图 3 CTC检测结直肠肿瘤的灵敏度和特异度 |

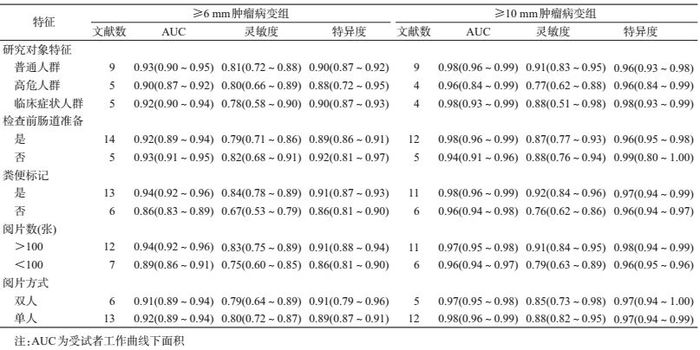

对筛查人群特征、检查前通便准备(是/否)、粪便标记(是/否)、阅片方式(双阅读/单人阅读)以及阅片人经验(>100/<100张CT片)进行亚组分析。≥6 mm肿瘤病变组(表 3),普通人群的AUC=0.93(0.90~0.95),灵敏度为0.81(0.72~0.88),特异度为0.90(0.87~0.92);高危人群分别为0.90(0.87~0.92)、0.80(0.66~0.89)、0.88(0.72~0.95);临床症状人群分别为0.92(0.90~0.94)、0.78(0.58~0.90)、0.90(0.87~0.93);进行粪便标记组分别为0.94(0.92~0.96)、0.84(0.78~0.89)、0.91(0.87~0.93),未进行粪便标记组分别为0.86(0.83~0.89)、0.67(0.53~0.79)、0.86(0.81~0.90);阅片人经验>100张CT片合并组分别为0.94(0.92~0.96)、0.83(0.75~0.89)、0.91(0.88~0.94),<100张CT片组分别为0.89(0.86~0.91)、0.75(0.60~0.85)、0.86(0.81~0.90)。≥10 mm组亚组分析结果见表 3。

6.发表偏倚:以诊断优势比(diagnostic odds ratio,DOR)为因变量,1/有效样本量的平方根[root(ESS)]为自变量,权重为有效样本容量。经线性回归检验,回归线的斜率为16.21,P=0.22,表明文献间不存在发表偏倚。

讨论在我国CT结直肠成像技术主要用于临床辅助诊断,并未应用于人群筛查。我国农村结直肠早诊早治技术方案为以危险因素数学模型评估问卷和FOBT为普通人群初筛手段,从普通人群中挑选出高危人群(评估结果阳性)进一步行结肠镜检查[31]。城市癌症筛查项目中结直肠癌筛查采用问卷评估出高危人群的直接行结肠镜检查[32]。

本文总体Meta分析结果显示,≥6 mm肿瘤病变组的AUC、灵敏度和特异度分别为0.92、0.80和0.89;≥10 mm肿瘤病变组AUC=0.98,灵敏度和特异度分别为0.87和0.97。说明CTC筛查结直肠肿瘤有较高的灵敏度和特异度,尤其针对高风险肿瘤(>10 mm)有更好的诊断价值。在大规模的肿瘤人群筛查时,不仅要考虑使用技术的准确度,还要考虑人群的依从性。荷兰基于人群的结直肠筛查发现结肠镜和CTC的参与率分别为22%和34%,进展期肿瘤的检出率分别为8.7%和6.1%,综合比较两种筛查手段的诊断率相似[33]。从卫生经济学角度评价,CTC筛查成本低于结直肠镜,是具有较高成本效益的结直肠肿瘤筛查手段[34]。

本研究对影响CTC诊断效能的因素进行亚组分析,结果显示各因素对特异度影响甚微,但是无论肿瘤病变的大小,检查前进行粪便标记,阅片人的经验丰富有助于提高诊断灵敏度。≥6 mm肿瘤病变组,粪便标记者和非标记者的灵敏度分别为0.84和0.67;阅片人经验丰富与相对不足者的灵敏度分别为0.83和0.75。≥10 mm肿瘤病变组粪便标记和非标记者的灵敏度分别为0.92和076;阅片人经验丰富与相对不足者的灵敏度分别为0.91和0.79。针对阅片人经验,有研究发现不同水平的阅片人(腹部影像学者、初级放射线医生和胃肠病学初学者)对CT图像解释的准确率相近[35]。

Plumb等[36]对粪隐血试验阳性的高危人群CTC检查结果进行荟萃分析,结直肠肿瘤≥6 mm的灵敏度为0.89,特异度为0.75,≥10 mm的由于数据不足无法呈现。本研究≥6 mm的高危人群灵敏度0.80,特异度0.88,两研究结果不一致的原因可能为本研究的高危人群不仅包括粪便隐血试验阳性人群,还包括结直肠癌的一级亲属、结直肠息肉史等其他高危人群。本研究对不同三类人群(普通人群、高危人群和有临床症状者)的CTC诊断效果汇总,发现其诊断效能无明显变化,提示无论是人群大规模筛查还是机会性筛查,CTC具有较好的诊断价值。

基于目前证据,CTC诊断结直肠肿瘤具有较高的灵敏度和特异度,是一种潜在的结肠肿瘤筛查手段。检查前进行粪便标记、经验丰富的阅片人有助于提高CTC的灵敏度。基于我国人群开展CTC筛查技术准确性研究是未来努力的重要方向。

利益冲突: 无

| [1] | Greuter MJ, Xu XM, Lew JB, et al. Modeling the Adenoma and Serrated pathway to Colorectal Cancer (ASCCA)[J]. Risk Anal, 2013, 34(5): 889–910. DOI:10.1111/risa.12137 |

| [2] |

张玥, 石菊芳, 黄慧瑶, 等.

中国人群结直肠癌疾病负担分析[J]. 中华流行病学杂志, 2015, 36(7): 709–714.

Zhang Y, Shi JF, Huang HY, et al. Burden of colorectal cancer in China[J]. Chin J Epidemiol, 2015, 36(7): 709–714. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2015.07.010 |

| [3] |

陈竺.全国第三次死因回顾抽样调查报告[M]. 北京: 中国协和医科大学出版社, 2008.

Chen Z.The third national death cause survey in China[M]. Beijing: China Union Medical University Press, 2008. |

| [4] | Brenner H, Kloor M, Pox CP. Colorectal cancer[J]. Lancet, 2014, 383(9927): 1490–1502. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61649-9 |

| [5] | Siegel R, DeSantis C, Virgo K, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2012[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2012, 62(4): 220–241. DOI:10.3322/caac.21149 |

| [6] | Lieberman D, Ladabaum U, Cruz-Correa M, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer and evolving issues for physicians and patients:a review[J]. JAMA, 2016, 316(20): 2135–2145. DOI:10.1001/jama.2016.17418 |

| [7] | Levin B, Lieberman DA, McFarland B, et al. Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008:a joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology[J]. Gastroenterology, 2008, 134(5): 1570–1595. DOI:10.1053/j.gastro.2008.02.002 |

| [8] | Benson VS, Atkin WS, Green J, et al. Toward standardizing and reporting colorectal cancer screening indicators on an international level:the International Colorectal Cancer Screening Network[J]. Int J Cancer, 2012, 130(12): 2961–2973. DOI:10.1002/ijc.26310 |

| [9] |

黄慧瑶, 石菊芳, 代敏.

中国大肠癌筛查的卫生经济学评价研究进展[J]. 中华预防医学杂志, 2015, 49(8): 747–751.

Huang HY, Shi JF, Dai M. Research progress in health economic evaluation of colorectal cancer screening in China[J]. Chin J Prev Med, 2015, 49(8): 747–751. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-9624.2015.08.017 |

| [10] | Spada C, Stoker J, Alarcon O, et al. Clinical indications for computed tomographic colonography:European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) and European Society of Gastrointestinal and Abdominal Radiology (ESGAR) Guideline[J]. Eur Radiol, 2015, 25(2): 331–345. DOI:10.1007/s00330-014-3435-z |

| [11] | Whiting P, Rutjes AWS, Reitsma JB, et al. The development of QUADAS:a tool for the quality assessment studies of diagnostic accuracy included in systematic reviews[J]. BMC Med Res Methodol, 2003, 10(3): 25. DOI:10.1186/1471-2288-3-25 |

| [12] | Fini L, Laghi L, Hassan C, et al. Noncathartic CT colonography to screen for colorectal neoplasia in subjects with a family history of colorectal cancer[J]. Radiology, 2014, 270(3): 784–790. DOI:10.1148/radiol.13130373 |

| [13] | Fletcher JG, Silva AC, Fidler JL, et al. Noncathartic CT colonography:image quality assessment and performance and in a screening cohort[J]. AJR Am J Roentgenol, 2013, 201(4): 787–794. DOI:10.2214/AJR.12.9225 |

| [14] | Lefere P, Silva C, Gryspeerdt S, et al. Teleradiology based CT colonography to screen a population group of a remote island; at average risk for colorectal cancer[J]. Eur J Radiol, 2013, 82(6): e262–267. DOI:10.1016/j.ejrad.2013.02.010 |

| [15] | Regge D, Della Monica P, Galatola G, et al. Efficacy of computer-aided detection as a second reader for 6-9-mm lesions at CT colonography:multicenter prospective trial[J]. Radiology, 2013, 266(1): 168–176. DOI:10.1148/radiol.12120376 |

| [16] | Mang T, Hermosillo G, Wolf M, et al. Time-efficient CT colonography interpretation using an advanced image-gallery-based, computer-aided "first-reader" workflow for the detection of colorectal adenomas[J]. Eur Radiol, 2012, 22(12): 2768–2779. DOI:10.1007/s00330-012-2522-2 |

| [17] | Johnson CD, Herman BA, Chen MH, et al. The national CT colonography trial:assessment of accuracy in participants 65 years of age and older[J]. Radiology, 2012, 263(2): 401–408. DOI:10.1148/radiol.12102177 |

| [18] | Zalis ME, Blake MA, Cai W, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of laxative-free computed tomographic colonography for detection of adenomatous polyps in asymptomatic adults:a prospective evaluation[J]. Ann Intern Med, 2012, 156(10): 692–702. DOI:10.7326/0003-4819-156-10-201205150-00005 |

| [19] | Heresbach D, Djabbari M, Riou F, et al. Accuracy of computed tomographic colonography in a nationwide multicentre trial, and its relation to radiologist expertise[J]. Gut, 2011, 60(5): 658–665. DOI:10.1136/gut.2010.225623 |

| [20] | Liedenbaum MH, van Rijn AF, de Vries AH, et al. Using CT colonography as a triage technique after a positive faecal occult blood test in colorectal cancer screening[J]. Gut, 2009, 58(9): 1242–1249. DOI:10.1136/gut.2009.176867 |

| [21] | Regge D, Laudi C, Galatola G, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of computed tomographic colonography for the detection of advanced neoplasia in individuals at increased risk of colorectal cancer[J]. JAMA, 2009, 301(23): 2453–2461. DOI:10.1001/jama.2009.832 |

| [22] | Graser A, Stieber P, Nagel D, et al. Comparison of CT colonography, colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy and faecal occult blood tests for the detection of advanced adenoma in an average risk population[J]. Gut, 2009, 58(2): 241–248. DOI:10.1136/gut.2008.156448 |

| [23] | Kim YS, Kim N, Kim SH, et al. The efficacy of intravenous contrast-enhanced 16-raw multidetector CT colonography for detecting patients with colorectal polyps in an asymptomatic population in Korea[J]. J Clin Gastroenterol, 2008, 42(7): 791–798. DOI:10.1097/MCG.0b013e31811edcb7 |

| [24] | Arnesen RB, Von Benzon E, Adamsen S, et al. Diagnostic performance of computed tomography colonography and colonoscopy:a prospective and validated analysis of 231 paired examinations[J]. Acta Radiol, 2007, 48(8): 831–837. DOI:10.1080/02841850701422096 |

| [25] | Rockey DC, Paulson E, Niedzwiecki D, et al. Analysis of air contrast barium enema, computed tomographic colonography, and colonoscopy:prospective comparison[J]. Lancet, 2005, 365(9456): 305–311. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17784-8 |

| [26] | Cotton PB, Durkalski VL, Pineau BC, et al. Computed tomographic colonography (virtual colonoscopy):a multicenter comparison with standard colonoscopy for detection of colorectal neoplasia[J]. JAMA, 2004, 291(14): 1713–1719. DOI:10.1001/jama.291.14.1713 |

| [27] | van Gelder RE, Nio CY, Florie J, et al. Computed tomographic colonography compared with colonoscopy in patients at increased risk for colorectal cancer[J]. Gastroenterology, 2004, 127(1): 41–48. DOI:10.1053/j.gastro.2004.03.055 |

| [28] | Iannaccone R, Laghi A, Catalano C, et al. Computed tomographic colonography without cathartic preparation for the detection of colorectal polyps[J]. Gastroenterology, 2004, 127(5): 1300–1311. DOI:10.1053/j.gastro.2004.08.025 |

| [29] | Pickhardt PJ, Choi JR, Hwang I, et al. Computed tomographic virtual colonoscopy to screen for colorectal neoplasia in asymptomatic adults[J]. N Engl J Med, 2003, 349(23): 2191–1200. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa031618 |

| [30] | Pineau BC, Paskett ED, Chen GJ, et al. Virtual colonoscopy using oral contrast compared with colonoscopy for the detection of patients with colorectal polyps[J]. Gastroenterology, 2003, 125(2): 304–310. DOI:10.1016/S0016-5085(03)00885-0 |

| [31] |

卫生部疾病预防控制局, 癌症早诊早治项目专家委员会.癌症早诊早治项目技术方案(2011年版)[M].北京:人民卫生出版社, 2011.

Bureau of Disease Prevention and Control, Ministry of Health of the People's Republic of China, Cancer Screening Program in Urban China Experts Committee. Technical plan of cancer screening program in urban China(2011)[M]. Beijing:People's Medical Publishing House, 2011. |

| [32] |

代敏, 石菊芳, 李霓.

中国城市癌症早诊早治项目设计及预期目标[J]. 中华预防医学杂志, 2014, 47(2): 179–182.

Dai M, Shi JF, Li N. Design and target of cancer screening program in urban China[J]. Chin J Prev Med, 2014, 47(2): 179–182. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-9624.2013.02.018 |

| [33] | Stoop EM, de Haan MC, de Wijkerslooth TR, et al. Participation and yield of colonoscopy versus non-cathartic CT colonography in population-based screening for colorectal cancer:a randomised controlled trial[J]. Lancet Oncol, 2012, 13(1): 55–64. DOI:10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70283-2 |

| [34] | Pyenson B, Pickhardt PJ, Sawhney TG, et al. Medicare cost of colorectal cancer screening:CT colonography vs. optical colonoscopy[J]. Abdom Imaging, 2015, 40(8): 2966–2976. DOI:10.1007/s00261-015-0538-1 |

| [35] | Rosenfeld G, Fu YT, Quiney B, et al. Does training and experience influence the accuracy of computed tomography colonography interpretation?[J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2014, 20(6): 1574–1581. DOI:10.3748/wjg.v20.i6.1574 |

| [36] | Plumb AA, Halligan S, Pendsé DA, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of CT colonography for the detection of colonic neoplasia after positive faecal occult blood testing:systematic review and Meta-analysis[J]. Eur Radiol, 2014, 24(5): 1049–1058. DOI:10.1007/s00330-014-3106-0 |

2017, Vol. 38

2017, Vol. 38