文章信息

- 张蕴伟, 高慧, 黄锟, 许媛媛, 盛杰, 陶芳标.

- Zhang Yunwei, Gao Hui, Huang Kun, Xu Yuanyuan, Sheng Jie, Tao Fangbiao.

- 孕早期邻苯二甲酸酯暴露与孕晚期空腹血糖水平关联的队列研究

- A cohort study on association between the first trimester phthalates exposure and fasting blood glucose level in the third trimester

- 中华流行病学杂志, 2017, 38(3): 388-392

- Chinese journal of Epidemiology, 2017, 38(3): 388-392

- http://dx.doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2017.03.023

-

文章历史

收稿日期: 2016-08-15

2. 230601 合肥, 人口健康与优生安徽省重点实验室

2. Anhui Provincial Laboratory for Population Health and Eugenics, Hefei 230601, China

邻苯二甲酸酯(PAE)作为一类增塑剂广泛应用于各类塑料制品中,用以增强塑料的弹性、透明度和耐久性。其中邻苯二甲酸二辛酯(DEHP)约占欧盟聚氯乙烯增塑剂市场的50.0%[1-2]。2009-2010年美国国家健康与营养调查(NHANES)报道,PAE代谢物在人群尿样中的检出率超过96.0%[3],脐血中15种PAE检出率为18.4%~100.0%[4]。有研究认为孕期PAE暴露与孕妇血糖水平关联,而2013年欧洲地区孕妇妊娠期糖尿病(GDM)患病率约为10.9%[5],马耳他2010年GDM报告率达到16.5%[6],我国GDM的发生率多数地区超过10.0%[7-9]。由于GDM与诸多不良妊娠结局有关联[10-12],且目前孕期PAE暴露与孕妇血糖水平关联性的研究较少且存在争议[13-14],为此本研究分析马鞍山优生优育出生队列(Ma’anshan Birth Cohort,MABC)中的孕妇,以探讨孕早期PAE暴露与孕晚期FPG间的关联性。

对象与方法1.研究对象:以MABC中2013年5月至2014年9月在马鞍山市妇幼保健院进行产前检查并符合纳入标准的3 474名孕妇为研究对象。纳入标准:①知情同意,自愿参加本研究;②年龄≥18岁;③孕周≤14周;④在马鞍山市妇幼保健院建卡且在该院产检和分娩;⑤无严重精神疾患,能理解并填写问卷题目。排除标准依据参考文献[15]。剔除妊娠期显性糖尿病和糖尿病合并妊娠11人,双胎9人,无PAE实验数据153人,缺失FPG值292人,共3 009人纳入研究。

2.研究方法:

(1)问卷调查和临床资料收集:于首次孕期体检(孕周≤14周)、孕24~28周和孕32~36周进行3次问卷调查,包括人口社会学信息(孕妇年龄、身高、文化程度、家庭收入、居住地等)、不良生活方式(孕前吸烟史、饮酒史等)、妊娠史及既往疾病史等及测量孕妇身高并询问孕前体重,计算孕前BMI。问卷调查同时收集孕妇晨尿样本和检测FPG。于孕24~28周采用75 g口服糖耐量试验(OGTT)诊断GDM,诊断标准按照“妊娠合并糖尿病诊治指南(2014)”[16],即FPG≥5.1 mmol/L或OGTT-1 h≥10.0 mmol/L或OGTT-2 h≥8.5 mmol/L中符合任意一项者。

(2)实验室检测:按高慧等[12]方法采用固相萃取-高效液相色谱-串联质谱法(SPE-HPLC-MS/MS)定量分析孕妇尿样中PAE代谢物浓度。包括邻苯二甲酸单甲酯(MMP)、邻苯二甲酸单乙酯(MEP)、邻苯二甲酸单丁酯(MBP)、邻苯二甲酸单(2-乙基-5-羟基己基)酯(MEHHP)、邻苯二甲酸单苄酯(MBzP)、邻苯二甲酸单(2-乙基己基)酯(MEHP)和邻苯二甲酸单(2-乙基-5-酮基己基)酯(MEOHP)7种代谢物。采用苦味酸法(试剂盒购于南京建成生物工程研究所)定量分析孕妇尿样中肌酐浓度。

3.统计学分析:运用Epi Data 3.0软件建立数据库,平行录入问卷调查资料。运用SPSS 13.0软件分析资料。将尿中各代谢物浓度进行自然对数转换后,数据服从正态分布。以自然对数转换后的孕早期PAE代谢物浓度为自变量,孕妇孕晚期FPG值为因变量,孕早期FPG水平为基线资料,调整孕妇年龄、孕前BMI、家庭人均月收入、生育史、孕周等混杂因素,同时将尿肌酐浓度也作为协变量放入线性回归模型中校正尿样稀释度[17]。在风险性研究中,根据孕妇孕晚期FPG水平将其分为正常组(FPG<5.1 mmol/L)和GDM组(FPG≥5.1 mmol/L),按照孕早期尿中PAE各代谢物浓度第50分位数(P50)分组,分为低暴露组和高暴露组,运用logistic回归模型分析不同暴露组别的孕妇孕晚期患GDM的风险。本研究将尿样中PAE代谢物浓度高于检出限(limit of detection,LOD)定义为检出,低于LOD的代谢物浓度采用

1.样本人群特征:3 009名孕妇诊断GDM 385人,患病率为12.8%;空腹血糖受损(IFG)4人,合并入正常组;糖耐量减低(IGT)67人。研究对象年龄18~42岁,平均(26.41±3.64)岁。孕前BMI平均(20.60±2.78)kg/m2,平均孕周为(25.62±1.03)周。居住在城镇的孕妇占78.1%,农村占21.9%。文化程度初中及以下占19.7%,高中或大专占53.6%,本科及以上占26.7%。家庭人均月收入<2 500元占26.0%,2 500~4 000元占42.9%,>4 000元占31.1%。吸烟和饮酒的比例分别为4.2%和8.3%。有9.3%的孕妇在此次怀孕前有过孕产史。

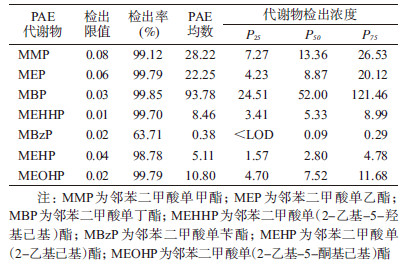

2.孕早期尿PAE代谢物检出率和暴露水平分布:7种PAE代谢物中,除MBzP检出率为63.71%外,其余代谢物检出率均>98.00%。低分子量PAE代谢物(MMP、MEP和MBP)的浓度较高分子量PAE代谢物(MEHHP、MBzP、MEHP和MEOHP)高,平均浓度最高的代谢物为MBP,浓度最低的为MBzP(表 1)。

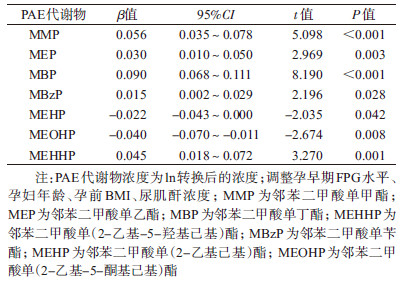

3.孕早期PAE暴露水平与孕晚期FPG水平的关联:单因素分析显示,年龄、孕前BMI与孕妇FPG水平显著关联。为防止孕早期FPG值干扰孕早期PAE暴露与孕晚期FPG值的关联性,将孕早期FPG值作为控制因素,分析孕早期PAE暴露水平对孕晚期FPG水平的影响。共线性检验显示各代谢物之间存在多重共线性,所以分别将各代谢物放入线性回归模型中分析。结果发现,低分子量PAE代谢物(MMP、MEP和MBP)浓度与FPG水平呈正相关,差异有统计学意义;高分子量PAE代谢物中MBzP、MEHHP浓度与FPG水平呈正相关,MEHP、MEOHP浓度与FPG水平呈负相关,差异有统计学意义。低分子量PAE代谢物总浓度(∑LMW)与FPG水平呈正相关,差异有统计学意义(表 2)。

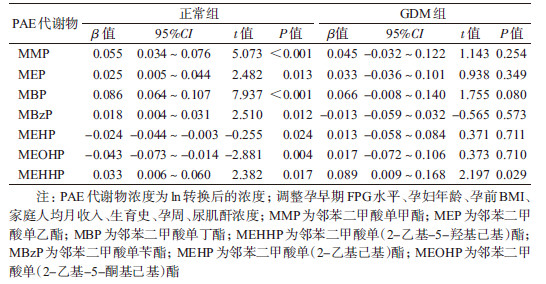

4.不同组别孕妇孕早期PAE暴露与孕晚期FPG水平的关联:根据GDM诊断结果将孕妇分为正常组和GDM组,分析两组PAE暴露与孕晚期FPG水平的关联(表 3)。结果显示,孕早期MMP、MEP、MBP、MBzP暴露与正常组FPG水平呈正相关,MEHP、MEOHP暴露与正常组FPG水平呈负相关,差异有统计学意义,但孕早期暴露与GDM组FPG水平关联的差异均无统计学意义;MEHHP暴露与正常组和GDM组FPG水平均呈正相关,∑LMW代谢物浓度与正常组和GDM组FPG水平也均呈正相关,差异有统计学意义。此外,MMP暴露与IGT孕妇孕晚期FPG水平呈正相关,差异有统计学意义,其余6种代谢物与IGT孕妇FPG水平的关联均无统计学意义。

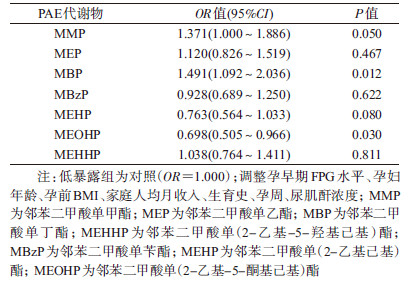

5.孕早期PAE暴露与孕晚期GDM的风险性:根据孕妇孕晚期FPG水平分为正常组和GDM组,按照孕早期尿PAE各代谢物浓度分为低暴露组和高暴露组,分析不同暴露组别的孕妇患GDM的风险性。表 4显示,MMP和MBP高暴露组孕妇孕晚期患GDM的风险分别是低暴露组孕妇的1.371倍和1.491倍,差异有统计学意义;MEOHP高暴露组孕妇孕晚期患GDM的风险是低暴露组的0.698倍,差异有统计学意义。

本研究探讨孕早期PAE暴露与孕晚期FPG水平间的关联性和孕晚期GDM发生的风险性,尿中MMP、MEP、MBP、MBzP、MEHHP浓度与FPG水平呈正相关,MEHP、MEOHP浓度与FPG水平呈负相关。孕早期MMP和MBP暴露会增加孕晚期GDM发生的风险,MEOHP暴露会降低孕晚期GDM发生的风险。此外,孕妇年龄、孕前BMI、家庭收入水平、生育史和孕周等因素也可影响GDM的发生,但未发现这些因素会影响PAE的暴露。

国内外关于孕期PAE暴露与FPG水平关联性的人群研究较少。Robledo等[13]研究发现尿中邻苯二甲酸一异丁基酯(MiBP)和MBzP浓度较高的孕妇,其孕期血糖水平低于浓度较低的孕妇,但Shapiro等[14]未发现孕期PAE暴露对GDM有影响。在其他人群的研究显示,PAE暴露会增加糖尿病的患病风险。一项12~80岁人群的研究发现,尿中PAE代谢物浓度与FPG水平呈显著正相关[18],另一项针对70岁老年人的研究显示MMP、MiBP和MEP会增加2型糖尿病的患病率,但未发现MEHP与2型糖尿病患病率的关联[19]。Watkins等[20]一项关于宫内及青春期PAE暴露及其代谢指标的研究表明,宫内暴露于MEP与青春期男性胰岛素分泌降低相关,宫内暴露于DEHP与青春期女性胰岛素生长因子1(IGF-1)升高相关,青春期女性暴露于DEHP与较高的IGF-1和胰岛素分泌水平相关,青春期男性暴露于MBzP与较低的IGF-1水平相关。

动物研究显示,染毒2周的实验组小鼠FPG水平显著高于对照组小鼠,胰岛素耐量实验表明染毒3周后的实验组小鼠胰岛素敏感性有轻微下降[21]。此外,染毒组小鼠胰岛素受体、胰岛素受体底物、血浆葡萄糖转运蛋白(GLUT4)等也有所降低[22]。Nora等[23]的研究发现,DEHP染毒虽然会导致胰岛素耐受性显著受损,但并不影响葡萄糖耐量、胰岛素抵抗指数、FPG、胰岛素、血清TG浓度等指标。这可能说明DEHP染毒不会引起全身水平的糖代谢障碍。

相关研究表明,PAE暴露会增加总DNA甲基化水平,并下调胰岛中β细胞生长和功能相关基因,孕期PAE暴露介导基因表观遗传学的改变是导致子代β细胞功能障碍和全身糖代谢异常的重要因素[24]。宫内暴露PAE会下调成年期子代胰岛素信号转导通路相关基因(GLUT4等)的表达,诱发葡萄糖代谢异常[25]。Rajesh等[26]的研究发现PAE通过下调细胞膜上GLUT4水平,进而干扰胰岛素信号分子的表达及其磷酸转移途径,降低葡萄糖的摄取和氧化。

虽然动物和人群研究均表明PAE暴露会影响糖代谢,但不同种类PAE的影响可能存在差异甚至相反,且孕期PAE暴露对孕妇FPG水平和GDM的影响也暂无定论,因此需要开展更深入的研究。本研究发现PAE代谢物对正常孕妇FPG水平的影响较GDM孕妇更为显著,这可能是由于GDM患者已发生明显的糖代谢紊乱,而PAE对于糖代谢的影响效应较弱,故而干扰了二者之间的关联性,但还需更多机制学方面的研究予以证实。PAE作为一种环境内分泌干扰物,其健康危害性已被大量研究证实,提示孕妇应当减少PAE的接触,防止对胎儿产生不良影响。

本文为大样本出生队列研究。先前关于孕期PAE对FPG水平影响的人群研究较少,本文为此方向的研究提供了新证据。本研究也存在缺陷,如单点尿样测量可能未能完全反映孕妇孕早期PAE暴露情况,但也有研究表明PAE暴露具有持续性和稳定性,因此单点采样能够反映近一段时间的暴露[27-30];此外,尿样稀释度仅采用尿肌酐浓度进行校正,而未测量尿比重,使得PAE水平可能有偏差。

利益冲突: 无

| [1] | Shin IS, Lee MY, Cho ES, et al. Effects of maternal exposure to di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) during pregnancy on susceptibility to neonatal asthma[J]. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol, 2014, 274(3): 402–407. DOI:10.1016/j.taap.2013.12.009 |

| [2] | Andrade AJ, Grande SW, Talsness CE, et al. A dose response study following in utero and lactational exposure to di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP):reproductive effects on adult male offspring rats[J]. Toxicology, 2006, 228(1): 85–97. DOI:10.1016/j.tox.2006.08.020 |

| [3] | Zota AR, Calafat AM, Woodruff TJ. Temporal trends in phthalate exposures:findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2001-2010[J]. Environ Health Perspect, 2014, 122(3): 235–241. DOI:10.1289/ehp.1306681 |

| [4] | Huang YJ, Li JN, Garcia JM, et al. Phthalate levels in cord blood are associated with preterm delivery and fetal growth parameters in Chinese women[J]. PLoS One, 2014, 9(2): e87430. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0087430 |

| [5] | International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas. International Diabetes Federation[M]. 6th ed. Brussels:Belgium, 2013. |

| [6] | Cuschieri S, Craus J, Savona-Ventura C, et al. The role of untimed blood glucose in screening for gestational diabetes mellitus in a high prevalent diabetic population[J]. Scientifica (Cairo), 2016, 2016: 3984024. DOI:10.1155/2016/3984024 |

| [7] |

王璇, 陈廷美, 于德纯, 等.

IADPSG标准下妊娠期糖尿病发病率及危险因素调查[J]. 实用医学杂志, 2014, 30(8): 1318–1320.

Wang X, Chen TM, Yu DC, et al. Investigations on the incidence of gestational diabetes mellitus diagnosed by IADPSG criteria and risk factors[J]. J Pract Med, 2014, 30(8): 1318–1320. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1006-5725.2014.08.045 |

| [8] |

郝宝珺, 沈洁, 万亨, 等.

广州市天河区妊娠期糖尿病发病率回顾性调查[J]. 中国糖尿病杂志, 2014, 22(7): 620–621.

Hao BJ, Shen J, Wan H, et al. A retrospective survey of the incidence of gestational diabetes mellitus in Guangzhou Tianhe district[J]. Chin J Diabetes, 2014, 22(7): 620–621. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1006-6187.2014.07.011 |

| [9] |

徐湘, 朱晓巍, 蒋艳敏, 等.

2748例住院孕妇妊娠期糖尿病发病率及危险因素的研究[J]. 南京医科大学学报:自然科学版, 2015(5): 695–698.

Xu X, Zhu XW, Jiang YM, et al. Study on the incidence and risk factors of gestational diabetes mellitus in 2748 pregnant women[J]. J Nanjing Med Uni, 2015(5): 695–698. DOI:10.7655/NYDXBNS20150520 |

| [10] |

汪漪. 妊娠期糖尿病与妊娠结局的关系[D]. 苏州: 苏州大学, 2014.

Wang Y. The relationship between gestational diabetes mellitus and pregnancy outcomes[D]. Suzhou:Suzhou University, 2014. |

| [11] | Cruz J, Grandía R, Padilla L, et al. Macrosomia predictors in infants born to Cuban mothers with gestational diabetes[J]. MEDICC Rev, 2015, 17(3): 27–32. |

| [12] |

高慧, 许媛媛, 孙丽, 等.

高效液相色谱-串联质谱法同时测定人尿液中7种邻苯二甲酸酯代谢物[J]. 色谱, 2015, 33(6): 622–627.

Gao H, Xu YY, Sun L, et al. Determination of seven phthalate metabolites in human urine by high performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry[J]. Chin J Chromatography, 2015, 33(6): 622–627. DOI:10.3724/SP.J.1123.2015.01037 |

| [13] | Robledo CA, Peck JD, Stoner J, et al. Urinary phthalate metabolite concentrations and blood glucose levels during pregnancy[J]. Int J Hyg Environ Health, 2015, 218(3): 324–330. DOI:10.1016/j.ijheh.2015.01.005 |

| [14] | Shapiro GD, Dodds L, Arbuckle TE, et al. Exposure to phthalates, bisphenol A and metals in pregnancy and the association with impaired glucose tolerance and gestational diabetes mellitus:The MIREC Study[J]. Environ Int, 2015, 83: 63–71. DOI:10.1016/j.envint.2015.05.016 |

| [15] |

毛雷婧, 葛星, 徐叶清, 等.

孕前体重指数和孕中期体重增加对妊娠期糖尿病发病影响的队列研究[J]. 中华流行病学杂志, 2015, 36(5): 416–420.

Mao LJ, Ge X, Xu YQ, et al. Pregestational body mass index, weight gain during first half of pregnancy and gestational diabetes mellitus:a prospective cohort study[J]. Chin J Epidemiol, 2015, 36(5): 416–420. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2015.05.002 |

| [16] |

中华医学会妇产科学分会产科学组, 中华医学会围产医学分会妊娠合并糖尿病协作组.

妊娠合并糖尿病诊治指南 (2014)[J]. 中华妇产科杂志, 2014, 49(8): 561–569.

Obstetrics and Gynecology Group of Chinese Medical Association, Association of Diabetic Pregnancy Study Group of Perinatal Medicine of Chinese Medical Association. Diagnosis and treatment of gestational diabetes mellitus (2014)[J]. Chin J Obstet Gynecol, 2014, 49(8): 561–569. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0529-567x.2014.08.001 |

| [17] | Kim JH, Park H, Lee J, et al. Association of diethylhexyl phthalate with obesity-related markers and body mass change from birth to 3 months of age[J]. J Epidemiol Community Health, 2016, 70(5): 466–472. DOI:10.1136/jech-2015-206315 |

| [18] | Huang T, Saxena AR, Isganaitis E, et al. Gender and racial/ethnic differences in the associations of urinary phthalate metabolites with markers of diabetes risk:National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001-2008[J]. Environ Health, 2014, 13(1): 6. DOI:10.1186/1476-069X-13-6 |

| [19] | Lind PM, Zethelius B, Lind L. Circulating levels of phthalate metabolites are associated with prevalent diabetes in the elderly[J]. Diabetes Care, 2012, 35(7): 1519–1524. DOI:10.2337/dc11-2396 |

| [20] | Watkins DJ, Peterson KE, Ferguson KK, et al. Relating phthalate and BPA exposure to metabolism in peripubescence:the role of exposure timing, sex, and puberty[J]. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2016, 101(1): 79–88. DOI:10.1210/jc.2015-2706 |

| [21] | Zhou W, Chen MH, Shi WB, et al. Influence of phthalates on glucose homeostasis and atherosclerosis in hyperlipidemic mice[J]. BMC Endocr Disord, 2015, 15: 13. DOI:10.1186/s12902-015-0015-4 |

| [22] | Priya VM, Mayilvanan C, Akilavalli N, et al. Lactational exposure of phthalate impairs insulin signaling in the cardiac muscle of F1 female albino rats[J]. Cardiovasc Toxicol, 2014, 14(1): 10–20. DOI:10.1007/s12012-013-9233-z |

| [23] | Nora K, Hesselbarth N, Gericke M, et al. Di-(2-ethylhexyl)-phthalate (DEHP) causes impaired adipocyte function and alters serum metabolites[J]. PLoS One, 2015, 10(12): e0143190. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0143190 |

| [24] | Rajesh P, Balasubramanian K. Gestational exposure to di (2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) impairs pancreatic β-cell function in F1 rat offspring[J]. Toxicol Lett, 2014, 232(1): 46–57. DOI:10.1016/j.toxlet.2014.09.025 |

| [25] | Rajesh P, Balasubramanian K. Phthalate exposure in utero causes epigenetic changes and impairs insulin signalling[J]. J Endocrinol, 2014, 223(1): 47–66. DOI:10.1530/JOE-14-0111 |

| [26] | Rajesh P, Sathish S, Srinivasan C, et al. Phthalate is associated with insulin resistance in adipose tissue of male rat:role of antioxidant vitamins[J]. J Cell Biochem, 2013, 114(3): 558–569. DOI:10.1002/jcb.24399 |

| [27] | Braun JM, Smith KW, Williams PL, et al. Variability of urinary phthalate metabolite and bisphenol A concentrations before and during pregnancy[J]. Environ Health Perspect, 2012, 120(5): 739–745. DOI:10.1289/ehp.1104139 |

| [28] | Dewalque L, Pirard C, Vandepaer S, et al. Temporal variability of urinary concentrations of phthalate metabolites, parabens and benzophenone-3 in a Belgian adult population[J]. Environ Res, 2015, 142: 414–423. DOI:10.1016/j.envres.2015.07.015 |

| [29] | Townsend MK, Franke AA, Li X, et al. Within-person reproducibility of urinary bisphenol A and phthalate metabolites over a 1 to 3 year period among women in the Nurses' Health Studies:a prospective cohort study[J]. Environ Health, 2013, 12(1): 80. DOI:10.1186/1476-069X-12-80 |

| [30] | Suzuki Y, Niwa M, Yoshinaga J, et al. Exposure assessment of phthalate esters in Japanese pregnant women by using urinary metabolite analysis[J]. Environ Health Prev Med, 2009, 14(3): 180–187. DOI:10.1007/s12199-009-0078-9 |

2017, Vol. 38

2017, Vol. 38