文章信息

- 赵永谦, 王黎君, 罗圆, 殷鹏, 黄正京, 刘涛, 林华亮, 肖建鹏, 李杏, 曾韦霖, 马文军, 周脉耕.

- Zhao Yongqian, Wang Lijun, Luo Yuan, Yin Peng, Huang Zhengjing, Liu Tao, Lin Hualiang, Xiao Jianpeng, Li Xing, Zeng Weilin, Ma Wenjun, Zhou Maigeng.

- 中国66个县/区日温差对人群死亡影响的时间序列研究

- Lagged effects of diurnal temperature range on mortality in 66 cities in China: a time-series study

- 中华流行病学杂志, 2017, 38(3): 290-296

- Chinese journal of Epidemiology, 2017, 38(3): 290-296

- http://dx.doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2017.03.004

-

文章历史

收稿日期: 2016-09-25

2. 100050 北京, 中国疾病预防控制中心慢性非传染性疾病预防控制中心;

3. 511430 广州, 广东省疾病预防控制中心 广东省公共卫生研究院

2. National Center for Chronic and Non-communicable Disease Control and Prevention, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Beijing 100050, China;

3. Guangdong Provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Guangdong Provincial Institute of Public Health, Guangzhou 511430, China

气候变化导致全球平均气温屡创新高,高温热浪等极端气候事件频发。已有许多研究关注高温热浪对健康的影响[1-5],但对日温差(某日内最高气温与最低气温的差值)的健康效应研究不多,且多局限在单个城市或较小地域内[6-12],大范围多城市的研究较少[12]。已有研究显示,日温差与居民死亡有关联,老年人和儿童是脆弱人群[13-17]。在全球变暖背景下,日最低气温增速高于最高气温增速,许多城市的日温差呈降低趋势[18-19],探索日温差健康效应的时空分布及其影响因素,对于适应气候变化,降低健康风险意义重大。因此,本研究选择中国66个县/区开展日温差与居民死亡关系的研究,了解日温差健康效应的时空变异对脆弱人群的影响,为制定适应气候变化的政策提供科学依据。

资料与方法1.研究现场:从死因监测点中选取人口超过20万的66个县/区以确保足量的日死亡数可用于模型拟合[20]。研究地点分散在中国北部、中部和南部,覆盖约4 400万人口。北部包括黑龙江省、辽宁省、吉林省、北京市、天津市、河北省、内蒙古自治区、山西省、陕西省、甘肃省、宁夏回族自治区、新疆维吾尔自治区和青海省等的23个县/区。中部包括江苏省、浙江省、安徽省、上海市、河南省、湖北省、湖南省、江西省和山东省等的25个县/区。南部包括四川省、贵州省、西藏自治区、云南省、重庆市、福建省、广东省和广西壮族自治区等的18个县/区。

2.资料来源:从中国CDC获取2006年1月1日至2011年12月31日居民死亡资料,包括死因、死亡日期、年龄、性别、文化程度和死亡地(医院内或院外)等信息。根据第10版国际疾病分类标识(ICD-10)对死因分类,非事故死亡为:A00~R99。

气象学资料从中国气象科学数据共享服务网(http://cdc.cma.gov.cn/home.do)获取,包括日平均温度(℃)、日最低温度(℃)、日最高温度(℃)和日相对湿度(%)等信息。

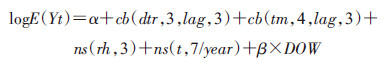

3.研究方法:利用分布滞后非线性模型(DLNM)分析单个社区日死亡数与日温差的关系,计算公式

(1)

(1)

式中,log()为连接函数,E()为t日的期望死亡数;cb表示交叉基函数;ns()表示自然样条函数;rh为相对湿度;dtr为日温差;tm为平均温度;t为1~n的整数序列,用以控制长期趋势和季节趋势;β是回归系数;DOW为控制“星期几效应”的分类变量。利用柯西泊松模型赤池信息标准(QAIC)选择非线性变量的自由度[21-22]:长期趋势为7/年,日相对湿度为3。利用交叉基函数生成日温差-滞后矩阵,其中日温差和滞后的自然样条函数自由度均为3,确定最大滞后为12以获取完整日温差效应[12]。同样使用交叉基函数生成平均温度矩阵,以在不同滞后期控制平均温度对居民死亡的影响,其中平均温度自然样条函数自由度为4,滞后期自由度为3,最大滞后亦为12[11]。

统计分析分两步进行,首先分析单个县/区日温差与死亡的关系以及极端日温差的效应。极端日温差效应分为极低日温差效应和极高日温差效应:极低日温差为P5的日温差,极高日温差则为P95的日温差。以日温差M为参考,评价极端日温差的死亡效应。

第二步利用Meta分析整合66个县/区的结果,分析全国范围内、北部、中部和南部日温差与日死亡的关系和极端日温差效应,以累计超额危险度(cumulative excess risk,CER)评价日温差的累计死亡效应,计算公式:

(2)

(2)

根据年龄(≥75岁组和<75岁组)、性别(男、女)和死亡地(院外死亡和院内死亡)分为不同亚组,以确定日温差死亡效应的脆弱人群。按季节分为夏秋季(5~10月)和冬春季(11月至次年4月),以寻找日温差死亡效应的季节模式。

4.统计学分析:采用R3.0.0软件进行统计分析,利用R包“dlnm”拟合分散滞后非线性模型,利用“metafor”包实现Meta分析。

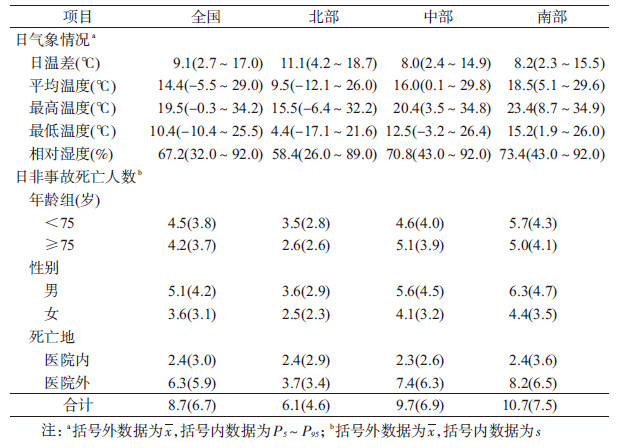

结果1.描述性分析:2006-2011年共1 260 913例死亡。不同区域居民死亡和气象特征均不同:北部、中部和南部县/区每日死亡人数均值为6.1、9.7和10.7人;日温差北部最大(11.1 ℃),中部最小(8.0 ℃);北部平均温度、最低温度、最高温度和相对湿度均最低,而南部则最高(表 1)。

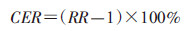

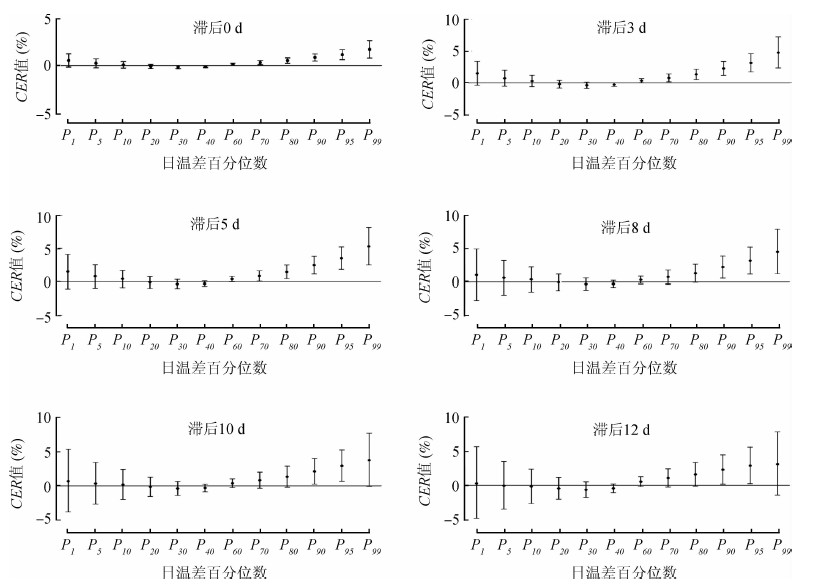

2.分布滞后非线性回归模型:在控制平均温度的效应后,比较不同滞后期日温差的累计死亡效应,可见全国范围内极低和极高日温差对死亡的影响差异有统计学意义(图 1)。极高日温差表现为急性死亡效应,在暴露当天出现,在滞后5 d达到峰值,然后逐渐下降。极低日温差的累计死亡效应随滞后时间增加而改变,但差异均无统计学意义。冬春季和夏秋季分析,极端日温差亦表现出相似的结果,且冬春季的极高日温差累计死亡效应强度和持续时间均高于夏秋季(图 2),冬春季极高日温差的累计死亡效应在滞后7 d达到峰值,夏秋季日温差则在滞后4 d达到峰值,在滞后7 d后基本消失。

|

| 图 1 2006-2011年不同百分位数日温差在不同滞后期累计超额危险度变化情况 |

|

| 图 2 不同季节不同百分位数日温差在不同滞后期累计超额危险度变化情况 |

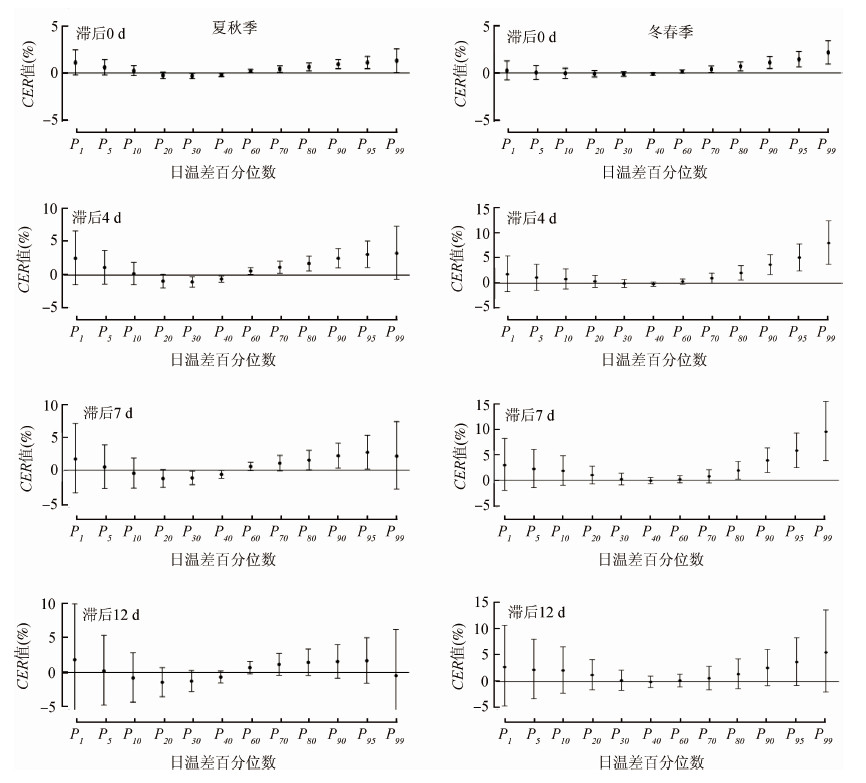

极端日温差对死亡的影响存在空间异质性(图 3,表 2)。各区域极低日温差的累计死亡效应差异均无统计学意义。对于极高日温差,南部和中部县/区的死亡效应在暴露当天即出现,中部县/区可持续12 d,南部则可持续8 d,北部则差异无统计学意义。

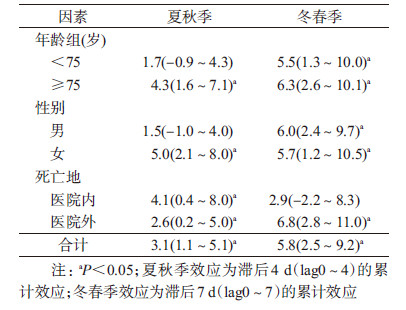

|

| 图 3 不同县/区极端日温差的累计超额危险度变化情况 |

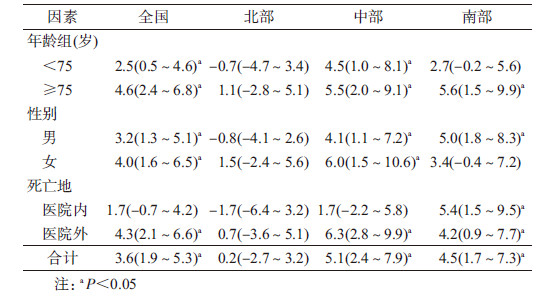

在不同县/区,各年龄、性别和死亡地人群极高日温差效应,差异有统计学意义(表 2)。在全国和中部县/区,老年人、女性和医院外人群的风险高于年轻人和男性;而在南部,极高日温差对男性和医院内人群的死亡风险高于女性和医院外人群。不同季节,极高日温差效应亦存在差异(表 3)。极高日温差在夏秋季和冬春季均存在明显的累计死亡效应,且在冬春季的效应更为明显(夏秋季最大CER=3.1%,95%CI:1.1%~5.1%;冬春季最大CER=5.8%,95%CI:2.5%~9.2%);无论冬春季和夏秋季,老年人的风险均高于年轻人;在夏秋季,男性和医院内人群的极高日温差的累计死亡效应高于女性和医院外人群,冬春季则相反。

在全球气候变化的大背景下,对日温差的健康效应愈发引人关注[6-12, 23],但少有研究对其空间异质性进行研究。本研究涉及66个县/区逾4 400万人口,研究结果显示,在控制平均温度的影响后,日温差与居民死亡之间存在非线性关系,暴露-反应曲线呈J形:极高日温差存在明显的累计死亡效应,而中等日温差和低日温差的累计死亡效应则不明显。不同于以往研究[24],本研究在控制平均温度滞后效应后,不同季节和不同地区极低日温差累计超额死亡效应差异均无统计学意义,可能是以前的研究大多只控制温度当天的效应,没有控制温度的滞后效应。

极高日温差对人群死亡的影响存在时空异质性:仅在南部和中部县/区存在累计超额死亡效应,且中部高于南部,冬春季高于夏秋季。由于人体温度调节系统处理突发情况能力有限,突发温度变异会引起人体相应变化,例如,血胆固醇、心率和血小板黏度均增加,而机体免疫能力下降[25-26],因此一日内较大的温度变化可导致人群中出现超额死亡。低纬度的南部城市冬春季温暖,当地居民在面对诸如2008年寒潮的大幅度降温时难以适应[27],可能是极高日温差对南部超额死亡风险较高的原因。相对于南部,中部冬春季寒冷且缺乏集中供暖设备,人群暴露于极高日温差机会更多,这可能是中部累计超额死亡风险高于南部的原因。而集中供暖,北部居民暴露的真实日温差远低于环境日温差,这可能是北部极高日温差的累计死亡效应差异无统计学意义的原因[1]。不同季节,极端日温差的效应亦有不同:极高日温差在夏秋季和冬春季均存在显著累计死亡效应,且在冬春季的死亡效应高于夏秋季,提示寒冷季节大幅度降温可能是极高日温差死亡效应主要原因,因此在冬春季应防范温度较大的变化对人群健康的危害。

社会经济水平差异与气候变化等环境风险高负担息息相关[28-31],中国广州地区的一项研究提示女性、老年人和文化程度较低人群对日温差更敏感[32];韩国首尔、仁川和大田城市研究极端日温差的死亡效应在老年人、女性及医院外人群中更显著[12]。本研究提示,极高日温差死亡效应在各年龄和性别的人群中均存在明显的死亡效应。在各城市不同季节,老年人极高日温差死亡风险高,这可能因为老年人存在基础疾病对温度变化更敏感。既往研究指出,不同性别和死亡地人群对温度效应的敏感程度受居住地影响[33],本研究结果亦表明,不同季节和地区人群中,极高日温差死亡效应的敏感人群不同。因此,应关注极高日温差对全人群的影响,并根据季节和居住地采取针对性的应对措施[34-35]。

本研究探索了中国不同县/区极端日温差的死亡效应及其差异,发现极端日温差对脆弱人群存在明显的健康影响,且存在时空异质性,这是目前我国日温差死亡效应的大数据研究,但研究仍有一定的局限性:首先,由于数据难以获取,未能将空气污染和流感数据纳入分析;第二,将环境温度作为个体暴露温度,但个体暴露温度可能受到使用空调等适应行为的影响而与室外温度不一致[36];第三,研究采用生态学设计方法,可能存在生态学方面的缺陷。

利益冲突: 无

| [1] | Basu R, Malig B. High ambient temperature and mortality in California:exploring the roles of age, disease, and mortality displacement[J]. Environ Res, 2011, 111(8): 1286–1292. DOI:10.1016/j.envres.2011.09.006 |

| [2] | Curriero FC, Heiner KS, Samet JM, et al. Temperature and mortality in 11 cities of the eastern United States[J]. Am J Epidemiol, 2002, 155(1): 80–87. DOI:10.1093/aje/155.1.80 |

| [3] | Guo YM, Barnett AG, Pan XC, et al. The impact of temperature on mortality in Tianjin, China:a case-crossover design with a distributed lag nonlinear model[J]. Environ Health Perspect, 2011, 119(12): 1719–1725. DOI:10.1289/ehp.1103598 |

| [4] | Tian ZX, Li SS, Zhang JL, et al. Ambient temperature and coronary heart disease mortality in Beijing, China:a time series study[J]. Environ Health, 2012, 11: 56. DOI:10.1186/1476-069X-11-56 |

| [5] | Zanobetti A, Schwartz J. Temperature and Mortality in Nine US Cities[J]. Epidemiology, 2008, 19(4): 563–570. DOI:10.1097/EDE.0b013e31816d652d |

| [6] | Kan HD, London SJ, Chen HL, et al. Diurnal temperature range and daily mortality in Shanghai, China[J]. Environ Res, 2007, 103(3): 424–431. DOI:10.1016/j.envres.2006.11.009 |

| [7] | Liang WM, Liu WP, Kuo HW. Diurnal temperature range and emergency room admissions for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Taiwan[J]. Int J Biometeorol, 2009, 53(1): 17–23. DOI:10.1007/s00484-008-0187-y |

| [8] | Cao JY, Cheng YX, Zhao N, et al. Diurnal temperature range is a risk factor for coronary heart disease death[J]. J Epidemiol, 2009, 19(6): 328–332. DOI:10.2188/jea.JE20080074 |

| [9] | Lim YH, Park AK, Kim H. Modifiers of diurnal temperature range and mortality association in six Korean cities[J]. Int J Biometeorol, 2012, 56(1): 33–42. DOI:10.1007/s00484-010-0395-0 |

| [10] | Chen GH, Zhang YH, Song GX, et al. Is diurnal temperature range a risk factor for acute stroke death?[J]. Int J Cardiol, 2007, 116(3): 408–409. DOI:10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.03.067 |

| [11] | Luo Y, Zhang YH, Liu T, et al. Lagged effect of diurnal temperature range on mortality in a subtropical megacity of China[J]. PLoS One, 2013, 8(2): e55280. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0055280 |

| [12] | Lim YH, Hong YC, Kim H. Effects of diurnal temperature range on cardiovascular and respiratory hospital admissions in Korea[J]. Sci Total Environ, 2012, 417/418: 55–60. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2011.12.048 |

| [13] | Barnett AG, Åström C. Commentary:what measure of temperature is the best predictor of mortality?[J]. Environ Res, 2012, 118: 149–151. DOI:10.1016/j.envres.2012.05.008 |

| [14] | Lin HL, Zhang YH, Xu YJ, et al. Temperature changes between neighboring days and mortality in summer:a distributed lag non-linear time series analysis[J]. PLoS One, 2013, 8(6): e66403. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0066403 |

| [15] | Guo YM, Barnett AG, Yu WW, et al. A large change in temperature between neighbouring days increases the risk of mortality[J]. PLoS One, 2011, 6(2): e16511. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0016511 |

| [16] | Lin S, Luo M, Walker RJ, et al. Extreme high temperatures and hospital admissions for respiratory and cardiovascular diseases[J]. Epidemiology, 2009, 20(5): 738–746. DOI:10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181ad5522 |

| [17] | Rocklöv J, Forsberg B. The effect of high ambient temperature on the elderly population in three regions of Sweden[J]. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2010, 7(6): 2607–2619. DOI:10.3390/ijerph7062607 |

| [18] | Lewis SC, Karoly DJ. Evaluation of historical diurnal temperature range trends in CMIP5 models[J]. J Climate, 2013, 26(22): 9077–9089. DOI:10.1175/JCLI-D-13-00032.1 |

| [19] | Ha J, Shin YS, Kim H. Distributed lag effects in the relationship between temperature and mortality in three major cities in South Korea[J]. Sci Total Environ, 2011, 409(18): 3274–3280. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2011.05.034 |

| [20] | Ma WJ, Zeng WL, Zhou MG, et al. The short-term effect of heat waves on mortality and its modifiers in China:an analysis from 66 communities[J]. Environ Int, 2015, 75: 103–109. DOI:10.1016/j.envint.2014.11.004 |

| [21] | Hastie TJ, Tibshirani RJ.Generalized additive models[M].London: Chapman and Hall, 1990: 587–602. |

| [22] | Gasparrini A, Armstrong B, Kenward MG. Distributed lag non-linear models[J]. Stat Med, 2010, 29(21): 2224–2234. DOI:10.1002/sim.3940 |

| [23] | Holopainen J, Helama S, Partonen T. Does diurnal temperature range influence seasonal suicide mortality? Assessment of daily data of the Helsinki metropolitan area from 1973 to 2010[J]. Int J Biometeorol, 2014, 58(6): 1039–1045. DOI:10.1007/s00484-013-0689-0 |

| [24] | Ding Z, Guo P, Xie F, et al. Impact of diurnal temperature range on mortality in a high plateau area in southwest China:a time series analysis[J]. Sci Total Environ, 2015, 526: 358–365. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.05.012 |

| [25] | Schneider A, Schuh A, Maetzel FK, et al. Weather-induced ischemia and arrhythmia in patients undergoing cardiac rehabilitation:another difference between men and women[J]. Int J Biometeorol, 2008, 52(6): 535–547. DOI:10.1007/s00484-008-0144-9 |

| [26] | Ballester F, Corella D, Pérez-Hoyos S, et al. Mortality as a function of temperature. A study in Valencia, Spain, 1991-1993[J]. Int J Epidemiol, 1997, 26(3): 551–561. DOI:10.1093/ije/26.3.551 |

| [27] | Xie HY, Yao ZB, Zhang YH, et al. Short-term effects of the 2008 cold spell on mortality in three subtropical cities in Guangdong province, China[J]. Environ Health Perspect, 2013, 121(2): 210–216. DOI:10.1289/ehp.1104541 |

| [28] | Anderson BG, Bell ML. Weather-related mortality:how heat, cold, and heat waves affect mortality in the United States[J]. Epidemiology, 2009, 20(2): 205–213. DOI:10.1097/EDE.0b013e318190ee08 |

| [29] | Anderson GB, Bell ML. Heat waves in the United States:mortality risk during heat waves and effect modification by heat wave characteristics in 43 U.S. communities[J]. Environ Health Perspect, 2011, 119(2): 210–218. DOI:10.1289/ehp.1002313 |

| [30] | Goggins WB, Chan EYY, Ng E, et al. Effect modification of the association between short-term meteorological factors and mortality by urban heat islands in Hong Kong[J]. PLoS One, 2012, 7(6): e38551. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0038551 |

| [31] | Medina-Ramón M, Zanobetti A, Cavanagh DP, et al. Extreme temperatures and mortality:assessing effect modification by personal characteristics and specific cause of death in a multi-city case-only analysis[J]. Environ Health Perspect, 2006, 114(9): 1331–1336. DOI:10.1289/ehp.9074 |

| [32] | Yang J, Liu HZ, Ou CQ, et al. Global climate change:impact of diurnal temperature range on mortality in Guangzhou, China[J]. Environ Pollut, 2013, 175: 131–136. DOI:10.1016/j.envpol.2012.12.021 |

| [33] | Basu R. High ambient temperature and mortality:a review of epidemiologic studies from 2001 to 2008[J]. Environ Health, 2009, 8: 40. DOI:10.1186/1476-069X-8-40 |

| [34] | De US, Khole M, Dandekar MM. Natural hazards associated with meteorological extreme events[J]. Nat Hazards, 2004, 31(2): 487–497. DOI:10.1023/B:NHAZ.0000023363.93647.c7 |

| [35] | Ebi KL, Schmier JK. A stitch in time:improving public health early warning systems for extreme weather events[J]. Epidemiol Rev, 2005, 27(1): 115–121. DOI:10.1093/epirev/mxi006 |

| [36] | Medina-Ramón M, Schwartz J. Temperature, temperature extremes, and mortality:a study of acclimatisation and effect modification in 50 US Cities[J]. Occup Environ Med, 2007, 64(12): 827–833. DOI:10.1136/oem.2007.033175 |

2017, Vol. 38

2017, Vol. 38