文章信息

- 谢双华, 王刚, 郭兰伟, 陈朔华, 苏凯, 李放, 昌盛, 冯小双, 吕章艳, 陈玉恒, 任建松, 崔宏, 李霓, 吴寿岭, 代敏, 赫捷 .

- Xie Shuanghua, Wang Gang, Guo Lanwei, Chen Shuohua, Su Kai, Li Fang, Chang Sheng, Feng Xiaoshuang, Lyu Zhangyan, Chen Yuheng, Ren Jiansong, Cui Hong, Li Ni, Wu Shouling, Dai Min, He Jie .

- 腰围与男性肺癌发病关系的前瞻性队列研究

- Relation between waist circumference and risk of male lung cancer incidence: a prospective cohort study

- 中华流行病学杂志, 2017, 38(2): 137-141

- CHINESE JOURNAL OF EPIDEMIOLOGY, 2017, 38(2): 137-141

- http://dx.doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2017.02.001

-

文章历史

收稿日期: 2016-08-01

2. 063000 唐山, 开滦总医院

2. Kailuan General Hospital, Tangshan 063000, China

肺癌是严重威胁人类健康的恶性肿瘤之一,居全球及我国恶性肿瘤发病和死亡的首位[1]。已知的危险因素包括吸烟、遗传和职业暴露等[2]。研究提示,BMI与肺癌发病风险呈负相关[3-5],但关于腹部脂肪蓄积的身体测量指标腰围与肺癌发病关系的研究较少[6-13],结论不一致。本研究利用前瞻性队列研究,探讨腰围与男性肺癌发病的关联及其强度。

对象与方法1. 研究对象:以开滦集团全体在职及离退休男性职工为调查对象,2006年5月建立的开滦集团男性动态队列。纳入标准:①年龄≥18岁;②签署知情同意书。排除标准:①至基线调查时已患恶性肿瘤;②基线调查时缺乏腰围测量数据。

2. 基线调查、随访和质量控制:基线调查由经过培训的医护人员采用统一设计的《开滦集团公司员工健康体检表》进行面对面调查,内容包括社会人口学特征、吸烟饮酒等生活方式、工作环境等信息。之后,由医护人员进行健康体检,体检包括查体、血液生化检查和影像学检查等。具体结果见文献[14]。基线调查后,研究对象参加开滦集团组织的每两年1次的健康体检,本研究借此进行相应随访,以了解研究对象恶性肿瘤发病、死亡及死亡原因等信息。对随访过程中的新发肿瘤病例,经培训的医护人员到其诊治的医院摘录病史资料,包括病理诊断、CT和核磁等检查结果以及其他临床诊断资料,以核实肺癌诊断;对死亡者除搜集病历外,医护人员还对其家属进行死因调查,并到公安部门进一步核实死因。同时,利用开滦集团医疗保险系统、唐山市医疗保险系统以及开滦总医院的出院信息系统提供的肿瘤发病数据作为补充,收集可能遗漏的肺癌新发病例。采用WHO国际癌症研究署(IARC)提供的CanReg 4软件对癌症新发病例进行录入和逻辑核查。

3. 自变量和结局变量:基线健康体检时,医护人员利用校准的体重秤和皮尺,根据标准方法测量调查对象的身高、体重、腰围。测身高和体重时要求被测者空腹、赤脚、脱帽、穿单衣、立正站立;测腰围时要求被测者直立,两臂自然下垂,不收腹,呼吸保持平稳,皮尺水平放在髋骨上、腰最细的部位。每项指标均测量2次,如果2次测量读数超过容许误差(1 cm或1 kg),则进行第3次测量,取接近的2次测量值均值用于分析。结合《中国成人超重和肥胖症预防与控制指南》中规定的男性腹部脂肪蓄积的腰围标准(男性腰围≥85 cm即可判定为腹部脂肪蓄积)及本研究人群腰围分布特征,采用腰围分布的五分位数进行分组:<80、80~、85~、90~、≥95 cm,并以相对正常的腰围组(80~cm组)为参比组,探索腰围与男性肺癌发病风险的关联。BMI<18.5 kg/m2为低体重,18.5 kg/m2≤BMI<25.0 kg/m2为正常体重,25.0 kg/m2≤BMI<30.0 kg/m2为超重,BMI≥30.0 kg/m2为肥胖。新发肺癌确诊采用病理诊断,若无病理诊断,由2名肿瘤科医生,结合其他临床信息,统一给出肺癌诊断意见。

4. 统计学分析:采用SAS 9.3软件对数据进行整理和分析。采用精确法计算队列中每名调查对象的观察人年数。进入队列的时间为首次参加体检的时间,出队列时间为首次诊断恶性肿瘤日期,死亡日期或本次随访截止日期(2014年12月31日)。采用 χ2检验比较不同特征的调查对象,其腰围分布的差异;以腰围分布为自变量,是否肺癌发病为因变量,采用多因素Cox比例风险回归模型分析腰围与肺癌发病风险的关系,计算粗HR值(95%CI)及调整了年龄、教育程度、吸烟状态、累计吸烟量、饮酒、工作环境、糖尿病史、体育锻炼情况后的HR值(95%CI)。趋势检验是将腰围的分组等级作为连续性变量纳入模型中检验,得到的P值即趋势检验P值。以P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。

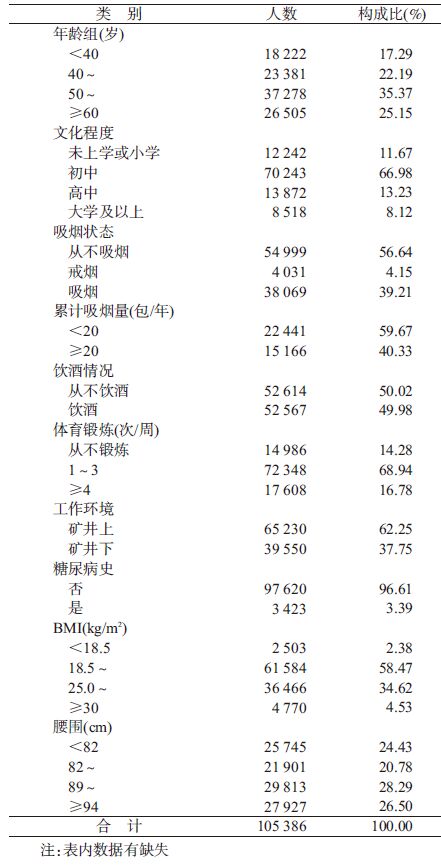

结 果1. 基本特征:截至2014年12月31日,105 386名19~104岁研究对象共计随访739 651.13人年,平均随访时间为7.00年,共收集肺癌新发病例707例,肺癌粗发病密度为95.59/10万人年。本研究队列中,调查对象年龄(51.69±13.22)岁,BMI均值为(24.30± 3.21)kg/m2,超重及肥胖率为39.15%(41 236人),腰围均值为(88.10±9.66) cm。吸烟、饮酒、体育锻炼频率≤3次/周分别占研究对象的39.21%(38 069人)、49.98%(52 567人)、83.22%(87 334人)。初中及以下学历、在矿井下工作的调查对象分别占78.65%(82 485人)、37.75%(39 550人)。见表 1。

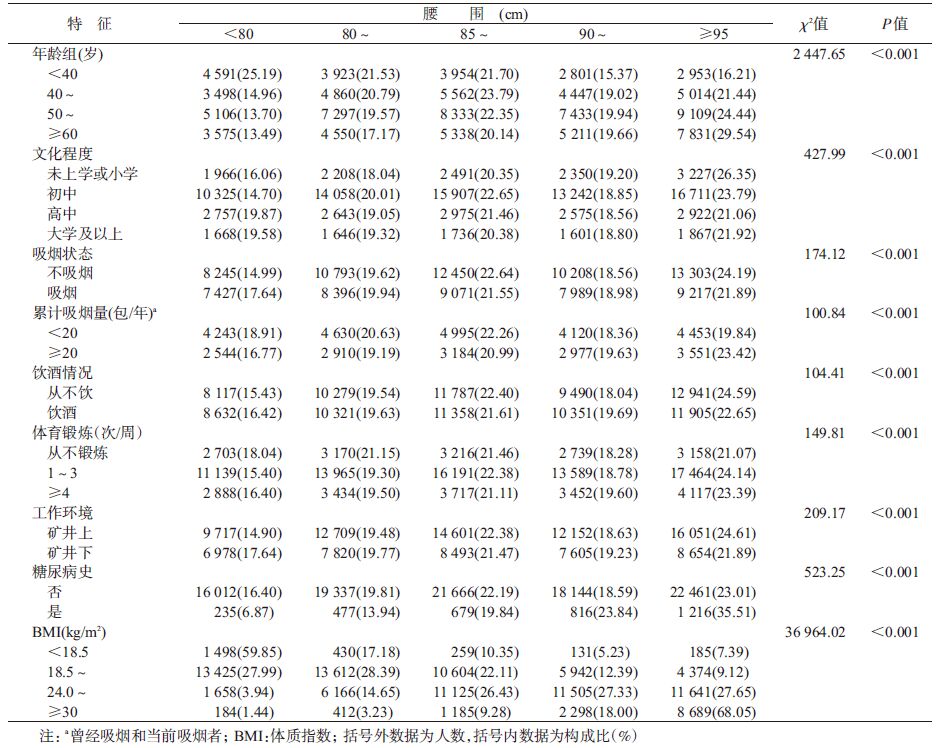

2. 研究对象腰围分布特征:不同特征的研究对象腰围分布不同。年龄较高,文化程度较低,不吸烟、不饮酒者腰围较高(均P<0.05),而矿井上工作、有糖尿病史、BMI较高者,其腰围也较高(均P<0.05)。见表 2。

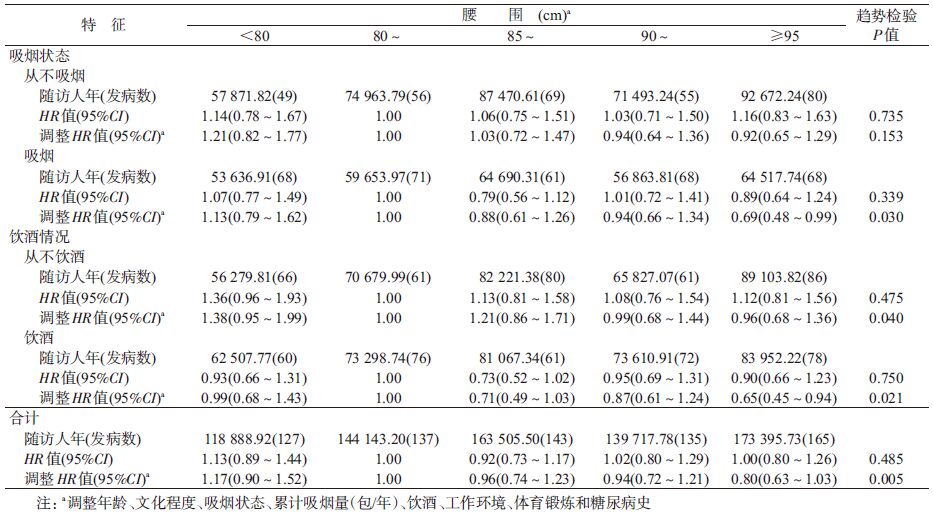

3. 不同腰围与肺癌发病风险分析:调整年龄、文化程度、吸烟状态、累计吸烟量、饮酒、体育锻炼、工作环境、糖尿病史因素后,以80~ cm组为参照组,腰围<80、85~、90~和≥95 cm组发生肺癌的HR值(95%CI)分别为1.17(0.90~1.52)、0.96 (0.74~1.23)、0.94(0.72~1.21)和0.80(0.63~1.03),趋势检验P=0.005。分别按吸烟、饮酒状态进行分层分析后发现,在吸烟者中,腰围与肺癌发病风险呈负相关,相比腰围80~cm组,≥95 cm组发生肺癌风险降低了31%(HR=0.69,95%CI:0.48~0.99)。在饮酒者中,相比腰围80~ cm组,≥95 cm组发生肺癌的风险可降低35%(HR=0.65,95%CI:0.45-0.94)。见表 3。

本研究结果显示,腰围可能与肺癌发病风险呈负相关。目前关于腰围与肺癌发生关系的研究较少,且结果不一致。Bethea等[11]在非洲裔美国女性中的研究显示,腰围可能与女性肺癌呈负相关,五分位数分类中次高组(33~36英寸,1英寸=2.54 cm)与最低组(<28英寸)相比,其发生肺癌的风险降低了37%(HR=0.63,95%CI:0.41~0.97),本研究结果与之相似。Folsom等[12]和Olson等[6]先后对美国同一老年女性队列进行随访研究。Folsom等[12]的研究未发现腰围与肺癌发生之间存在相关性,而Olson等[6]对腰围与不同病理组织类型肺癌发病关系进行进一步研究,结果显示,对于小细胞肺癌和鳞状细胞肺癌,腰围可增加其发病风险,而对于肺腺癌,未发现腰围与其发病之间存在相关性。Olson等[6]和Kabat等[9]分别对不同的美国老年女性队列进行随访研究发现,腰围与老年女性肺癌发病风险呈正相关,但该正相关性主要表现在吸烟人群中,在不吸烟人群中,未发现腰围与肺癌发病风险之间存在正相关关系。因此,研究人群的一致性(不同性别、年龄和种族)、肺癌病理组织学类型的差异,以及吸烟的混杂因素在一定程度上可以解释本研究与其他研究间结果的不一致性。腰围与肺癌发生的生物学机制目前尚未明确,可能与激素、胰岛素抵抗、瘦素和慢性炎症等相关[15-17],需要进一步研究。

本研究的设计避免了回忆偏倚对研究结果的影响,同时,研究对象腰围等身体测量指标均由经培训的医护人员采用统一的标准测量而得,避免了因自报而导致的分类偏倚。

本研究存在局限性。已有研究提示,腰围与肺癌关系可能与肺癌不同的病理组织学类型相关,本研究未能进一步分析腰围与不同病理组织学类型肺癌发生的关系。此外,未能对肺部既往疾病史、肺癌家族史等可能的危险因素进行调整、缺乏被动吸烟和大气污染等环境暴露因素数据等。

本研究结果提示,腰围与中国男性肺癌发生风险可能呈负相关;但有关腰围与肺癌发病的关系,尚待进一步研究。

利益冲突: 无

| [1] | Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics,2012[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2015, 65(2): 87–108. DOI:10.3322/caac.21262 |

| [2] | World Cancer Research Fund,American Institute for Cancer Research. Food,nutrition,physical activity,and the prevention of cancer:a global perspective[R]. Washington DC:AICR,2007. |

| [3] | Renehan AG, Tyson M, Egger M, et al. Body-mass index and incidence of cancer:a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective observational studies[J]. Lancet, 2008, 371(9612): 569–578. DOI:10.1016/s0140-6736(08)60269-x |

| [4] | Yang Y, Dong JY, Sun KK, et al. Obesity and incidence of lung cancer:a meta-analysis[J]. Int J Cancer, 2013, 132(5): 1162–1169. DOI:10.1002/ijc.27719 |

| [5] | Li XL, Bai YS, Wang SH, et al. Association of body mass index with chromosome damage levels and lung cancer risk among males[J]. Sci Rep, 2015, 5: 9458. DOI:10.1038/srep09458 |

| [6] | Olson JE, Yang P, Schmitz K, et al. Differential association of body mass index and fat distribution with three major histologic types of lung cancer:evidence from a cohort of older women[J]. Am J Epidemiol, 2002, 156(7): 606–615. DOI:10.1093/aje/kwf084 |

| [7] | Leitzmann MF, Moore SC, Koster A, et al. Waist circumference as compared with body-mass index in predicting mortality from specific causes[J]. PLoS One, 2011, 6(4): e18582. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0018582 |

| [8] | Lam TK, Moore SC, Brinton LA, et al. Anthropometric measures and physical activity and the risk of lung cancer in never-smokers:a prospective cohort study[J]. PLoS One, 2013, 8(8): e70672. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0070672 |

| [9] | Kabat GC, Kim M, Hunt JR, et al. Body mass index and waist circumference in relation to lung cancer risk in the Women's Health Initiative[J]. Am J Epidemiol, 2008, 168(2): 158–169. DOI:10.1093/aje/kwn109 |

| [10] | Drinkard CR, Sellers TA, Potter JD, et al. Association of body mass index and body fat distribution with risk of lung cancer in older women[J]. Am J Epidemiol, 1995, 142(6): 600–607. DOI:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117681 |

| [11] | Bethea TN, Rosenberg L, Charlot M, et al. Obesity in relation to lung cancer incidence in African American women[J]. Cancer Causes Control, 2013, 24(9): 1695–1703. DOI:10.1007/s10552-013-0245-6 |

| [12] | Folsom AR, Kushi LH, Anderson KE, et al. Associations of general and abdominal obesity with multiple health outcomes in older women:the Iowa Women's Health Study[J]. Arch Intern Med, 2000, 160(14): 2117–2128. DOI:10.1001/archinte.160.14.2117 |

| [13] | Dewi NU, Boshuizen HC, Johansson M, et al. Anthropometry and the risk of lung cancer in EPIC[J]. Am J Epidemiol, 2016, 184(2): 129–139. DOI:10.1093/aje/kwv298 |

| [14] |

郭兰伟, 李霓, 王刚, 等.

BMI与恶性肿瘤发病风险的前瞻性队列研究[J]. 中华流行病学杂志, 2014, 35(3): 231–236.

Guo LW, Li N, Wang G, et al. Body mass index and cancer incidence:a prospective cohort study in northern China[J]. Chin J Epidemiol, 2014, 35(3): 231–236. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2014.03.003 |

| [15] | Petridou ET, Sergentanis TN, Antonopoulos CN, et al. Insulin resistance:an independent risk factor for lung cancer[J]. Metabolism, 2011, 60(8): 1100–1106. DOI:10.1016/j.metabol.2010.12.002 |

| [16] | Lessard A, Alméras N, Turcotte H, et al. Adiposity and pulmonary function:relationship with body fat distribution and systemic inflammation[J]. Clin Invest Med, 2011, 34(2): e64–70. |

| [17] | Renehan AG, Zwahlen M, Egger M. Adiposity and cancer risk:new mechanistic insights from epidemiology[J]. Nat Rev Cancer, 2015, 15(8): 484–498. DOI:10.1038/nrc3967 |

2017, Vol. 38

2017, Vol. 38