文章信息

- 董丽, 胡尚英, 张倩, 冯瑞梅, 张莉, 赵雪莲, 马俊飞, 史少东, 张询, 潘秦镜, 章文华, 乔友林, 赵方辉 .

- Dong Li, Hu Shangying, Zhang Qian, Feng Ruimei, Zhang Li, Zhao Xuelian, Ma Junfei, Shi Shaodong, Zhang Xun, Pan Qinjing, Zhang Wenhua, Qiao Youlin, Zhao Fanghui .

- 山西省宫颈癌筛查队列中人乳头瘤病毒基因型别分布10年动态变化规律研究

- Changes in genotype prevalence of human papillomavirus over 10-year follow-up of a cervical cancer screening cohort

- 中华流行病学杂志, 2017, 38(1): 20-25

- Chinese journal of Epidemiology, 2017, 38(1): 20-25

- http://dx.doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2017.01.004

-

文章历史

收稿日期: 2016-07-08

2. 046200 长治, 山西省襄垣县妇幼保健院

2. Xiangyuan County Women and Children's Hospital, Changzhi 046200, China

随着高危型人乳头瘤病毒(HR-HPV)感染作为宫颈癌发生的必要病因得到证实[1-3],针对HR-HPV为靶点的分子技术,包括基于杂交捕获原理的HC2技术和PCR为原理的Cobas 4800技术已在筛查中得到广泛应用,并在筛查灵敏度、结果可重复性以及筛查宫颈腺癌等方面体现出优于传统细胞学的特点[4-7]。2015年美国妇科肿瘤协会及美国阴道镜和宫颈病理学会等组织发布的早期宫颈癌和癌前病变筛查指南推荐的筛查暂行指南建议HR-HPV检测用于宫颈癌初筛[6-7],宫颈癌的筛查方法正逐渐从传统细胞学为基础的形态学筛查向HPV为基础的分子筛查转变[8]。

通过早期筛查发现宫颈癌及癌前病变并给予及早治疗是降低宫颈癌发病率和死亡率的重要途径[9-10]。目前国际上多个发达国家已经建立了国家范围内的宫颈癌筛查体系,我国也正通过重大公共卫生服务项目“两癌筛查”等不断扩大宫颈癌的筛查覆盖率。但在相对稳定的筛查人群中,随着定期筛查和治疗病变,阻断筛查个体HPV自然感染过程的同时[11],筛查人群自然的HPV型别分布模式也可能发生相应改变。现有研究或以横断面研究形式针对一般筛查人群描述其HPV型别的分布特征[12-13],或以临床研究形式针对患者个体探讨治疗后HPV再感染或清除的变化趋势[11, 14]。本研究利用山西省襄垣县宫颈癌筛查队列中2005-2014年3次随访人群的流行病资料和实验室检测指标,评估宫颈癌筛查队列HPV型别分布的10年动态变化规律,并进一步从不同病理级别进行分层分析,以及对多重感染随筛查年龄的变化角度进行分析。

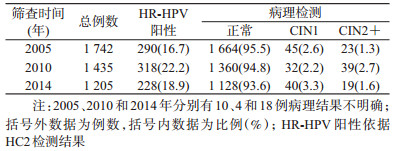

资料与方法1.研究流程:1999年6月,在我国宫颈癌高发区山西省襄垣县,采用整群抽样方法选取1 997名35~45岁女性,建立了宫颈癌筛查队列(SPOCCSⅠ队列),所有女性均进行6项检测(HPV检查的自我取样、医生取样以及荧光分光镜检、液基细胞学检测、醋酸染色后直接肉眼观察和阴道镜检查),并在阴道镜下行4象限随机活检和颈管搔刮(ECC)[15-16]。一经病理组织学确诊为宫颈上皮内瘤变2级及以上(CIN2+),则被建议以LEEP手术等临床手段进行治疗。并于2005年(n=1 742)、2010年(n=1 435)和2014年(n=1 205)通过对该人群子宫颈完整者采用HPV DNA检测、液基细胞学检查和醋酸染色(VIA)肉眼观察(2014年未做VIA)进行阶段性随访,任一阳性者转诊阴道镜检查,异常者取直接活检或4象限随机活检。此外还收集了筛查人群的人口学特征、吸烟、初次性行为年龄、本人及其配偶的婚外性行为等流行病学危险因素。因1999年无剩余标本,本研究仅对2005年和2010年既往保存和2014年新收集的宫颈细胞学标本进行基因型别检测,研究流程见图 1。

|

| 图 1 SPOCCS Ⅰ队列随访流程 |

2.随访疾病结局的确定:以2005年1 742例研究对象作为分析总体,随访终点指标为CIN2+,一旦出现结局则终止对该对象的随访。疾病结局以组织病理学结果为准,如未达到临床上活检采集要求而无病理学结果者,根据其HPV检测、细胞学检查和阴道镜检结果综合判定其最终结局[16-19]。

3.检测方法:

(1)HR-HPV DNA检测:宫颈脱落细胞学标本送至中国医学科学院肿瘤医院行杂交捕获HR-HPV检测(HC2,Qiagen)。该技术以混合探针RNA-DNA杂交形式检测13种高危型HPV(HPV16、18、31、33、35、39、45、51、52、56、58、59和68),但不能单独区分每一型别。标本中DNA含量>1.0 pg/ml者为HR-HPV阳性。

(2)线性反向探针杂交技术(LiPA)为基础的HPV基因分型检测:取-70 ℃保存的HR-HPV DNA检测结果为阳性者的剩余宫颈脱落细胞学标本,采用SPF10为引物(DDL诊断公司,荷兰)、PCR为基础的LiPA(比利时Innogenetics公司)进行HPV基因型别的检测。该技术可分别识别28种HPV型别,包括13种HR-HPV型别(涵盖HC2检测型别),3种可疑致癌型HPV型别(HPV26、53和66)和12种低危型别(HPV6、11、40、43、44、54、69、70、71、73、74和82),检测结果阳性为LiPA-HPV阳性。

4.统计学分析:利用EpiData 3.1软件编译数据库。采用双录入和双核查,确保数据准确无误。采用SPSS 18.0软件进行分析,运用Pearson χ2检验对比随访研究对象和失访对象的一般特征,采用线性混合模型比较随访期间总人群、病理结果正常以及CIN1人群中不同型别HPV感染率的变化,采用线性趋势χ2检验比较随访期间CIN2+人群中不同型别HPV感染率的变化。检验水准为α=0.05。

结果1.随访对象基本特征:1999年基线筛查的1 997例中,有1 742例符合标准者参加了2005年随访,其中23例经病理确诊为CIN2+,在排除92例非宫颈原因子宫切除(子宫肌瘤等)、死亡和宫颈疾病子宫切除(CIN2+)和192例失访者后,1 435例符合随访标准者参加了2010年随访,其中39例为新发CIN2+,随访率为89.0%。按照相同标准排除34例不符合随访标准的病例和234例失访者后,2014年共1 205例参加了随访,其中19例为新发CIN2+,随访率为75.0%(表 1)。本研究以2005年随访的1 742例作为分析总体,对比2010、2014年每个访视中随访对象和失访对象其HPV感染率、吸烟、初次性行为年龄、本人及其配偶的婚外性行为等危险因素的差异,结果显示差异均无统计学意义(P>0.05)。提示随行人群的总体代表性较好。

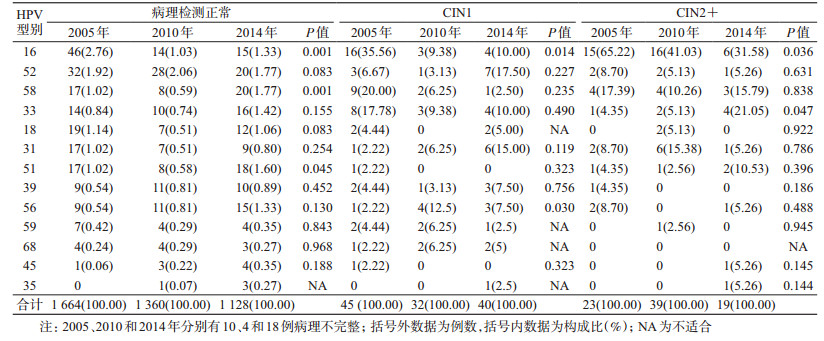

2.总人群中HPV型别分布特征随时间的动态变化趋势:队列人群中最常见为HPV16和52型别,但排列次序具有时间变化趋势。2005年HPV16最高,阳性率为4.6%,其他常见型别按降序排列依次为HPV52(2.2%)、58(1.7%)、33(1.4%)、18(1.3%)、51(1.1%)、31(1.1%)和56(1.1%),2010年HPV16和52阳性率均为2.2%,HPV58、33、31、56均为1.0%,2014年HPV52为优势型别(2.3%),略高于HPV16(2.2%),其他常见型别为HPV58(1.9%)、33(1.9%)、51(1.8%)、56(1.4%)和18(1.2%),线性混合模型估算结果显示,HPV16人群感染率随时间下降有统计学意义(F=8.125,P<0.001),HPV33、51和58感染率随时间变化均表现为略微下降后升高(F=3.048,P=0.048;F=3.824,P=0.022;F=3.803,P=0.023)。HPV52感染率比较稳定,随时间变化不明显。其他高危型别如HPV18、31、35、39、56等感染率随时间的动态变化趋势亦不明显(P>0.05)。见图 2。

|

| 图 2 SPOCCS Ⅰ队列总人群中不同HR-HPV型别分布 |

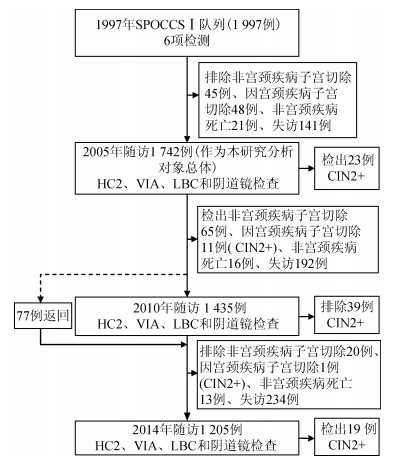

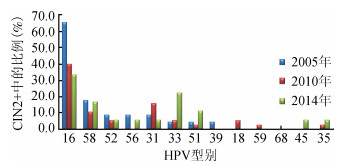

3.不同病理级别人群HR-HPV型别分布随时间的动态变化:采用线性混合模型分析显示,正常人群中HPV16感染率随时间有下降趋势(F=7.165,P=0.001),HPV51和58感染率随时间变化均表现为略微下降后升高(F=3.109,P=0.045,F=7.184,P=0.001),其他型别变化不明显。在CIN1人群中,HPV16感染率同样随时间下降(F=4.526,P=0.014),HPV56感染率明显上升,其他型别无明显变化(P>0.05)。在CIN2+人群中,HPV16检出率随着随访时间呈下降趋势,由2005年的65.22%,经2010年的41.03%下降至2014年的31.58%(χ2=4.420,P=0.036),HPV33所占比例明显上升,从2005年4.35%,经2010年5.13%,提高至2014年21.05%(χ2=3.950,P=0.047),HPV51虽然有上升趋势,但差异无统计学意义。其他高危型别随筛查时间动态变化趋势不明显(图 3、表 2)。

|

| 图 3 SPOCCSⅠ队列CIN2+人群中不同HR-HPV型别感染的分布 |

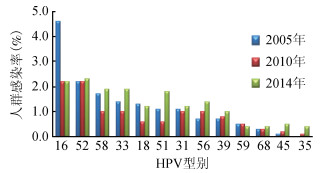

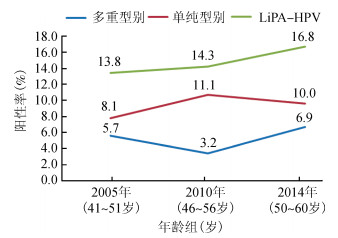

4.多重HPV感染随年龄的变化趋势:依据基因分型结果,随访研究对象HPV阳性率随着年龄增长呈现升高趋势,由2005年的13.8%、2010年14.3%升高至2014年的16.8%。进一步按单一型别和多重型别感染划分为单纯感染和多重感染进行线性混合模型分析,结果显示,多重感染率在筛查过程中随年龄的增长有所变化(F=10.689,P<0.001),从2005年(41~51岁)时的5.7%,下降到2010年(46~56岁)的3.2%,之后回到2014年(50~60岁)的6.9%(图 4)。

|

| 图 4 SPOCCSⅠ队列中多重HPV感染的年龄变化趋势 |

国内外大量资料显示,HPV型别分布特征存在地区差异。在世界范围内,细胞学检测结果正常人群中HPV16、18、31、58、52为常见感染型别,其中HPV16为几乎所有地区最常见的型别,HPV52在非洲地区东部、日本和中国台湾地区更为常见。本研究基于SPOCCSⅠ队列的长期随访,结果显示,HPV16和52是中国人群常见的感染型别,这与国内大多数横断面研究结果一致[20-22]。但进一步研究还发现在筛查期间HPV16感染率逐渐下降,而HPV52成为主要感染型别,表现为2005年HPV16在总人群中感染率高达6.7%,远高于HPV52(2.2%)、58(1.7%)等常见型别;5年后筛查,人群中HPV16型和52的感染率近乎一致(均为2.2%);10年后筛查,HPV52型(2.3%)高于HPV16型(2.2%),成为优势型别。此外,其他部分高危型别如HPV33、51和58等在总人群中感染率上升,当进一步针对病变程度分层分析后,发现主要发生改变的仍然是HPV16,其感染比例在每个病理级别中均随筛查过程而呈现下降趋势,其中可能包括两方面原因。一方面,可能与女性一生中HPV感染率及感染型别自然史随年龄增长的变化规律有关[23]。Argyri等[23]通过横断面观察14~70岁女性基因型别变化规律的研究也发现,随着年龄增长,HPV16感染率呈现下降趋势,其中50岁以后的年龄人群中感染率下降尤为明显。这与本研究结果相吻合。此外,另有国外研究报道女性在围绝经期(45~50岁)会出现HPV感染的第二个高峰[24-26]。本研究结果显示中国女性在41~60岁时HPV感染率一直维持在较高水平,且随年龄增长HPV阳性率逐渐升高,与国外研究报道基本吻合[24, 26]。本研究结果还显示,HPV多重感染率随年龄增长有明显波动,并在51~60岁时突然增高。这是伴随HPV16和52优势型别转变的又一特征性变化,提示两者可能存在共同的影响因素。前瞻性队列研究显示在开始性行为后的3年内46%女性可感染HPV,但大多数感染可能在1~2年内自动清除[27-28],而大龄女性免疫能力下降,尤其是围绝经期女性因生理因素造成体内激素改变,清除既往感染和新发感染的能力减弱,更易出现HPV感染和多重型别共同感染的现象。此外,围绝经期女性或其配偶性行为方式改变也可能是女性HPV型别分布发生变化的影响因素之一[29-30]。

SPOCCSⅠ队列在筛查过程中对检出的宫颈癌或癌前病变者进行临床干预。目前CIN2作为临床干预的阈值已列入宫颈筛查异常结果管理规范[6]。根据大规模横断面研究证实HPV16在中国人群宫颈癌及CIN2+中的感染率分别为76.7%和68.7%,HPV52相应感染率分别为2.2%和6.5%[31]。虽然本研究人群中发展为CIN2+的数量较少,但也显示筛查初期CIN2+的HPV16感染率为65.2%,HPV52为8.7%,在CIN2+患者得到治疗的同时,HPV16感染也会清除,其在人群中感染率会在一定程度上出现相应的降低。前瞻性队列研究结果显示,不同型别HPV致宫颈癌能力存在较大差异[32-34],且感染后癌前病变的出现时间亦不尽相同。一项对波特兰20 514例女性宫颈癌筛查的长期随访研究结果表明,HPV16阳性者10年间发展为CIN3+的累积发病风险(CIR)高达17.2%,但筛查出的病例均集中于早期,随访15个月时CIN3+的CIR接近9.0%,39个月时已接近13.0%,之后病例检出速度明显减缓[33]。鉴于HPV16是致宫颈癌能力最强的型别,且近期发病风险高,因此在筛查初期从总队列早期剔除的人数最多。这可能部分解释本研究队列人群中HPV16感染率随筛查时间延长所占比例降低的原因[35-36]。

本研究基于我国目前随访时间最长的宫颈癌筛查队列使我们有机会了解长期筛查过程中HPV基因型别的动态变化趋势。但研究中也存在一定局限性,如1999年无剩余的宫颈脱落细胞学标本,因而无法获得基线时HPV基因分型结果;研究中仅针对HC2阳性标本进行基因分型检测,估算不同HR-HPV人群感染率时默认HC2阴性即为所有高危型别均为阴性,因此可能低估了不同型别HPV相应的阳性率。

总之,基于本研究提示的宫颈癌筛查队列中HR-HPV感染型别随时间动态变化的规律,建议针对有宫颈癌筛查史的人群进行HPV检测时,尤其是采用HPV基因分型技术进行宫颈癌筛查应考虑HPV型别分布动态变化的特点。

利益冲突: 无

| [1] | Walboomers JMM, Jacobs MV, Manos MM, et al. Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide[J]. J Pathol , 1999, 189(1) : 12–19. DOI:10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199909)189:1 < 12::AID-PATH431>3.0.CO; 2-F |

| [2] | Schiffman MH, Bauer HM, Hoover RN, et al. Epidemiologic evidence showing that human papillomavirus infection causes most cervical intraepithelial neoplasia[J]. J Natl Cancer Inst , 1993, 85(12) : 958–964. DOI:10.1093/jnci/85.12.958 |

| [3] | Castle PE, Glass AG, Rush BB, et al. Clinical human papillomavirus detection forecasts cervical cancer risk in women over 18 years of follow-up[J]. J Clin Oncol , 2012, 30(25) : 3044–3050. DOI:10.1200/JCO.2011.38.8389 |

| [4] | Ronco G, Giorgi-Rossi P, Carozzi F, et al. Efficacy of human papillomavirus testing for the detection of invasive cervical cancers and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia:a randomised controlled trial[J]. Lancet Oncol , 2010, 11(3) : 249–257. DOI:10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70360-2 |

| [5] | Castle PE, Stoler MH, Wright TC Jr, et al. Performance of carcinogenic human papillomavirus (HPV) testing and HPV16 or HPV18 genotyping for cervical cancer screening of women aged 25 years and older:a subanalysis of the ATHENA study[J]. Lancet Oncol , 2011, 12(9) : 880–890. DOI:10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70188-7 |

| [6] | Massad LS, Einstein MH, Huh WK, et al. 2012 updated consensus guidelines for the management of abnormal cervical cancer screening tests and cancer precursors[J]. J Low Genit Tract Dis , 2013, 17(Suppl 5) : S1–27. DOI:10.1097/LGT.0b013e318287d329 |

| [7] | Huh WK, Ault KA, Chelmow D, et al. Use of primary high-risk human papillomavirus testing for cervical cancer screening:interim clinical guidance[J]. Gynecol Oncol , 2015, 136(2) : 178–182. DOI:10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.12.022 |

| [8] | Dijkstra MG, Snijders PJF, Arbyn M, et al. Cervical cancer screening:on the way to a shift from cytology to full molecular screening[J]. Ann Oncol , 2014, 25(5) : 927–935. DOI:10.1093/annonc/mdt538 |

| [9] | Su SY, Huang JY, Ho CC, et al. Evidence for cervical cancer mortality with screening program in Taiwan, 1981-2010:age-period-cohort model[J]. BMC Public Health , 2013, 13 : 13. DOI:10.1186/1471-2458-13-13 |

| [10] | Castanon A, Landy R, Sasieni P. By how much could screening by primary human papillomavirus testing reduce cervical cancer incidence in England?[J]. J Med Screen , 2016. DOI:10.1177/0969141316654197 |

| [11] | Pirtea L, Grigoras D, Matusz P, et al. Human papilloma virus persistence after cone excision in women with cervical high grade squamous intraepithelial lesion:a prospective study[J]. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol , 2016, 2016 : 3076380. DOI:10.1155/2016/3076380 |

| [12] | de Sanjosé S, Diaz M, Castellsagué X, et al. Worldwide prevalence and genotype distribution of cervical human papillomavirus DNA in women with normal cytology:a meta-analysis[J]. Lancet Infect Dis , 2007, 7(7) : 453–459. DOI:10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70158-5 |

| [13] | Zeng ZY, Yang HT, Li ZB, et al. Prevalence and genotype distribution of HPV infection in China:analysis of 51, 345 HPV genotyping results from China's Largest CAP Certified Laboratory[J]. J Cancer , 2016, 7(9) : 1037–1043. DOI:10.7150/jca.14971 |

| [14] | Gosvig CF, Huusom LD, Andersen KK, et al. Long-term follow-up of the risk for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or worse in HPV-negative women after conization[J]. Int J Cancer , 2015, 137(12) : 2927–2933. DOI:10.1002/ijc.29673 |

| [15] |

赵方辉, 李楠, 马俊飞, 等.

山西省襄垣县妇女人乳头状瘤病毒感染与宫颈癌关系的研究[J]. 中华流行病学杂志 , 2001, 22(5) : 375–378.

Zhao FH, Li N, Ma JF, et al. Study of the association between human papillomavirus infection and cervical cancer in Xiangyuan coumty, Shanxi province[J]. Chin J Epidemol , 2001, 22(5) : 375–378. DOI:10.3760/j.issn.0254-6450.2001.05.020 |

| [16] | Belinson J, Qiao YL, Pretorius R, et al. Shanxi Province Cervical Cancer Screening Study:a cross-sectional comparative trial of multiple techniques to detect cervical neoplasia[J]. Gynecol Oncol , 2001, 83(2) : 439–444. DOI:10.1006/gyno.2001.6370 |

| [17] | Shi JF, Belinson JL, Zhao FH, et al. Human papillomavirus testing for cervical cancer screening:results from a 6-year prospective study in rural China[J]. Am J Epidemiol , 2009, 170(6) : 708–716. DOI:10.1093/aje/kwp188 |

| [18] | Wang SM, Colombara D, Shi JF, et al. Six-year regression and progression of cervical lesions of different human papillomavirus viral loads in varied histological diagnoses[J]. Int J Gynecol Cancer , 2013, 23(4) : 716–723. DOI:10.1097/IGC.0b013e318286a95d |

| [19] | Zhao FH, Hu SY, Zhang Q, et al. Risk assessment to guide cervical screening strategies in a large Chinese population[J]. Int J Cancer , 2016, 138(11) : 2639–2647. DOI:10.1002/ijc.30012 |

| [20] | Wang R, Guo XL, Wisman GBA, et al. Nationwide prevalence of human papillomavirus infection and viral genotype distribution in 37 cities in China[J]. BMC Infect Dis , 2015, 15 : 257. DOI:10.1186/s12879-015-0998-5 |

| [21] | Wang SM, Li J, Qiao YL. HPV prevalence and genotyping in the cervix of Chinese women[J]. Front Med Chin , 2010, 4(3) : 259–263. DOI:10.1007/s11684-010-0095-5 |

| [22] | Ye J, Cheng XD, Chen XJ, et al. Prevalence and risk profile of cervical human papillomavirus infection in Zhejiang province, southeast China:a population-based study[J]. Virol J , 2010, 7 : 66. DOI:10.1186/1743-422X-7-66 |

| [23] | Argyri E, Papaspyridakos S, Tsimplaki E, et al. A cross sectional study of HPV type prevalence according to age and cytology[J]. BMC Infect Dis , 2013, 13 : 53. DOI:10.1186/1471-2334-13-53 |

| [24] | Castle PE, Schiffman M, Herrero R, et al. A prospective study of age trends in cervical human papillomavirus acquisition and persistence in Guanacaste, Costa Rica[J]. J Infect Dis , 2005, 191(11) : 1808–1816. DOI:10.1086/428779 |

| [25] | Centurioni MG, Puppo A, Merlo DF, et al. Prevalence of human papillomavirus cervical infection in an Italian asymptomatic population[J]. BMC Infect Dis , 2005, 5 : 77. DOI:10.1186/1471-2334-5-77 |

| [26] | Hernández-Hernández DM, Ornelas-Bernal L, Guido-Jiménez M, et al. Association between high-risk human papillomavirus DNA load and precursor lesions of cervical cancer in Mexican women[J]. Gynecol Oncol , 2003, 90(2) : 310–317. DOI:10.1016/S0090-8258(03)00320-2 |

| [27] | Ho GYF, Bierman R, Beardsley L, et al. Natural history of cervicovaginal papillomavirus infection in young women[J]. N Engl J Med , 1998, 338(7) : 423–428. DOI:10.1056/NEJM199802123380703 |

| [28] | Moscicki AB, Shiboski S, Broering J, et al. The natural history of human papillomavirus infection as measured by repeated DNA testing in adolescent and young women[J]. J Pediatr , 1998, 132(2) : 277–284. DOI:10.1016/S0022-3476(98)70445-7 |

| [29] | Moscicki AB, Schiffman M, Kjaer S, et al. Chapter 5:updating the natural history of HPV and anogenital cancer[J]. Vaccine , 2006, 30(Suppl 5) : F24–33. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.06.018 |

| [30] | Althoff KN, Paul P, Burke AE, et al. Correlates of cervicovaginal human papillomavirus detection in perimenopausal women[J]. J Women's Health , 2009, 18(9) : 1341–1346. DOI:10.1089/jwh.2008.1223 |

| [31] | Chen W, Zhang X, Molijn A, et al. Human papillomavirus type-distribution in cervical cancer in China:the importance of HPV16 and 18[J]. Cancer Causes Control , 2009, 20(9) : 1705–1713. DOI:10.1007/s10552-009-9422-z |

| [32] | Chen HC, Schiffman M, Lin CY, et al. Persistence of type-specific human papillomavirus infection and increased long-term risk of cervical cancer[J]. J Natl Cancer Inst , 2011, 103(18) : 1387–1396. DOI:10.1093/jnci/djr283 |

| [33] | Khan MJ, Castle PE, Lorincz AT, et al. The elevated 10-year risk of cervical precancer and cancer in women with human papillomavirus (HPV) type 16 or 18 and the possible utility of type-specific HPV testing in clinical practice[J]. J Natl Cancer Inst , 2005, 97(14) : 1072–1079. DOI:10.1093/jnci/dji187 |

| [34] | Lyons YA, Kamat AA, Zhou HJ, et al. Non-16/18 high-risk HPV infection predicts disease persistence and progression in women with an initial interpretation of LSIL[J]. Cancer Cytopathol , 2015, 123(7) : 435–442. DOI:10.1002/cncy.21549 |

| [35] | Smith JS, Lindsay L, Hoots B, et al. Human papillomavirus type distribution in invasive cervical cancer and high-grade cervical lesions:a meta-analysis update[J]. Int J Cancer , 2007, 121(3) : 621–632. DOI:10.1002/ijc.22527 |

| [36] | Clifford GM, Smith JS, Plummer M, et al. Human papillomavirus types in invasive cervical cancer worldwide:a meta-analysis[J]. Br J Cancer , 2003, 88(1) : 63–73. DOI:10.1038/sj.bjc.6600688 |

2017, Vol. 38

2017, Vol. 38