文章信息

- 李静, 罗书全, 丁贤彬, 杨军, 李京, 刘小波, 高景宏, 许磊, 唐文革, 刘起勇.

- Li Jing, Luo Shuquan, Ding Xianbin, Yang Jun, Li Jing, Liu Xiaobo, Gao Jinghong, Xu Lei, Tang Wenge, Liu Qiyong.

- 重庆市逐日温度对人群死亡及寿命损失年影响的研究

- Influence of daily ambient temperature on mortality and years of life lost in Chongqing

- 中华流行病学杂志, 2016, 37(3): 375-380

- Chinese Journal of Epidemiology, 2016, 37(3): 375-380

- http://dx.doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2016.03.017

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期: 2015-08-07

2. 400042 重庆市疾病预防控制中心;

3. 250012 济南, 山东大学公共卫生学院

2. Chongqing Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Chongqing 400042, China;

3. Department of Epidemiology, School of Public Health, Shandong University, Jinan 250012, China

气候变化对人类健康的影响近年来备受关注,而如何应对气候变化引起的温度变化对健康的影响已成为全球性公共卫生挑战[1, 2]。在全球气候变暖的背景下,我国高温热浪将变得更加频繁,且持续时间更长[3]。因而来自不同地区的气象健康研究将为全面评估气候变化对我国人群健康影响提供依据。重庆市夏季气候具有 “高温、高湿、少风”的特点,高温酷暑尤为突出,此外冬季无集中供暖,因而人群对气温变化可能更为敏感。以往气温与健康关系研究的结局指标主要是人群死亡率或患病率,而该两指标只考虑死亡人数或患病人数而忽略健康结局在不同年龄的差异[4]。寿命损失年(YLL)是评价劳动力人口健康水平敏感指标,可反映死亡对整个社会造成的损害,是精确测量疾病负担的方法,普遍应用于确定引起人群早死的主要死因[5]。为此本研究分析重庆市极端气温对人群死亡率及YLL的影响。

资料与方法1. 研究资料:源自重庆市CDC 2010-2013年重庆市主城区每天空气污染数据,包括空气中粒径≤10 μm颗粒物(PM10)、二氧化硫(SO2)、二氧化氮(NO2);同期气象数据来自中国气象科学数据共享服务网(http://cdc.nmic.cn/home.do),包括日均温度、日均相对湿度、日均气压;同期全人群死亡个案数据来源于重庆市CDC,包括性别、年龄、住址、出生日期、死亡日期及死亡原因的国际疾病编码(ICD- 10)等;从WHO网站(http://apps.who.int/gho/data/view.main.60340?lang=en)下载2012年和2013年中国男、女性分年龄段期望寿命表。本研究重点关注非意外(ICD-10:A00~R99)死亡、心血管系统疾病(I00~I99)死亡及呼吸系统疾病(J00~J99)死亡。

2. 指标及定义:平均温度的最大滞后期设定为30 d,各变量及温度滞后维度的自由度通过查阅文献和赤池信息准则(Akaike information criterion)确定。采用平均温度从P90到P99升高1 ℃致人群死亡的RR值与YLL变化估计高温效应;采用平均温度从P1到P10降低1 ℃致人群死亡的RR值与YLL变化估计低温效应。

3. 统计学分析:采用R 3.0.3软件和分布滞后非线性模型(distributed lag non-linear models)拟合不同滞后时间的暴露-反应非线性关系[6]。以往研究提示每天死亡人数为计数资料且为小概率事件,服从Poisson分布,而YLL服从正态分布,因此基本模型为

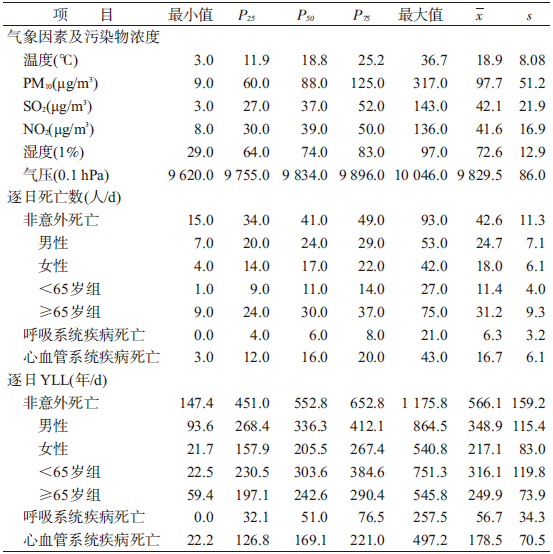

1. 基本情况:2010-2013年重庆市日均气温为18.9 ℃,日均非意外死亡42.6人(其中男性24.7人,≥65岁年龄组31.2人,心血管系统疾病16.7人,呼吸系统疾病6.3人),日均非意外死亡的YLL为566.1年(其中男性348.9年,<65岁年龄组316.1年,心血管系统疾病为178.5年,呼吸系统疾病为56.7年)。见表 1。

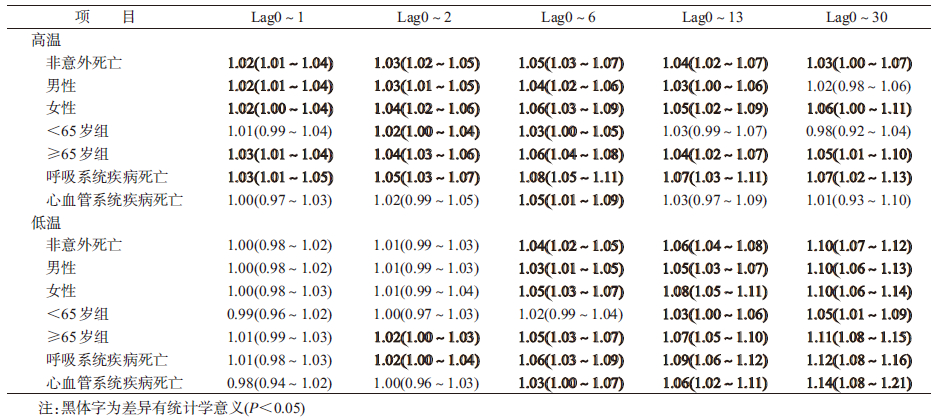

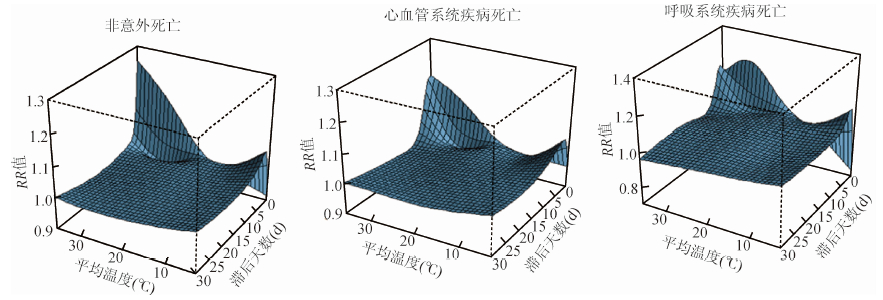

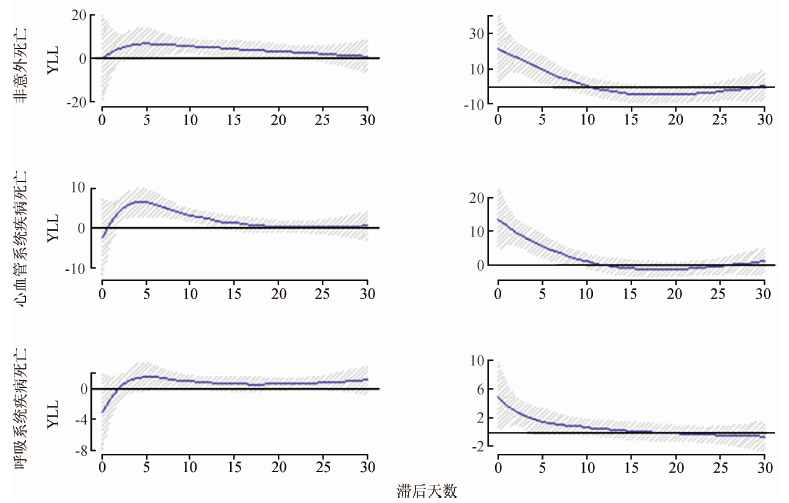

日均气温与非意外、心血管系统疾病及呼吸系统疾病死亡的日死亡人数及日YLL呈“U”或“W”形(图 1),即高温和低温时,以上各类疾病死亡的风险增加。考虑温度对死亡影响的滞后效应,高温在当天就表现出危害效应,随着滞后天数的增加,死亡风险不断增加,滞后7 d时达到最大,随后的1周死亡风险及YLL降低,直至效应消失。而低温在滞后1周后才表现出危害效应,随着滞后天数的增加,死亡风险及YLL不断增加,可持续至低温发生后的第30天(图 2~4)。

|

| 图 1 2010-2013年重庆市逐日平均气温对逐日死亡人数及YLL的影响 |

|

| 图 2 不同滞后天数的日均气温对不同死因RR值影响的3D分析 |

|

| 图 3 不同滞后时间的日均气温对非意外死亡RR值的等高线图 |

|

| 图 4 不同滞后天数下高温及低温对不同死因YLL的影响 |

2. 高温对不同人群及疾病死亡风险的影响:高温对人群日死亡人数及YLL的影响均在滞后7 d时达到最大值,因此计算累积7 d的RR值及YLL。结果显示,当日平均气温从30.3 ℃升至34.5 ℃时(即高温时),气温每升高1 ℃,人群非意外死亡的累积相对危险度(CRR)为1.05(95%CI:1.03~1.07),其中女性死亡风险明显大于男性,≥65岁年龄组明显高于<65岁组的死亡风险,呼吸系统及心血管系统疾病死亡风险的CRR值分别为1.08(95%CI:1.05~1.11)和1.05(95%CI:1.01~1.09)。

高温时,日均气温每升高1 ℃,人群非意外死亡的YLL增加23.81(95%CI:12.31~35.31) 年,其中男性的YLL大于女性,≥65岁年龄组的YLL明显大于<65岁组,死于呼吸系统疾病和心血管系统疾病的YLL分别为14.34(95%CI:8.98~19.70)年和4.43(95%CI:1.64~7.21)年(表 2,3)。

3. 低温对不同人群及疾病死亡风险的影响:低温最重要的健康危害发生在滞后0~14 d,结果显示,低温滞后14 d对人群非意外死亡的CRR值为1.06(95%CI:1.04~1.08),其中女性大于男性;低温对≥65岁组人群有危害,而对<65岁组人群并未显示出危害效应;低温对呼吸系统及心血管系统疾病死亡的CRR值分别为1.09(95%CI:1.06~1.12)和1.06(95%CI:1.02~1.11)。

低温引起非意外死亡的YLL为23.34(95%CI:10.04~36.64)年,低温对女性及≥65岁年龄组人群影响更大,差异有统计学意义,死于呼吸系统疾病的YLL为16.39(95%CI:10.19~22.59年)年,低温可增加心血管系统疾病死亡的YLL但差异无统计学意义(表 2、3)。

讨 论本研究提示重庆市日均气温对人群死亡的效应呈现“U”或“W”形;高温的影响急促短暂,而低温的影响通常滞后1周但持续较长时间。目前国内外研究结果也显示温度与死亡的关系通常描述为“U”、“V”、 “J” 或“W”形[7, 8, 9],即高温效应滞后期短,而低温滞后期长[10];日均温度与YLL的关系曲线为“U”形,在高温和低温时YLL增加,低温对YLL影响的滞后期长,高温的滞后期短[11, 12],与本研究结果一致。

重庆地区极端高温和低温均可明显增加非意外、心血管系统及呼吸系统疾病死亡的风险及YLL,与国内外相关研究结果一致[4, 9, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16]。分析极端气温对敏感人群的影响显示,极端气温对≥65岁年龄组人群的死亡风险和YLL影响更大。极端高温时,女性的死亡风险大于男性,然而男性的YLL却大于女性,因此高温对年轻男性影响更大。低温时,女性的死亡风险及YLL均大于男性,低温对女性的影响更大。重庆市室外高温作业人员大部分是男性,加之夏季高温酷暑明显,室外作业缺乏有效的降温设施,因而高温对年轻男性影响更大。而冬季无集中供暖设施,且湿度大,当地居民更易受室外冷空气的影响。由于性别的生理差异,以及社会经济地位及承受压力能力的差异[17],从而导致低温时女性更加敏感。

本研究存在局限性。首先,气象数据仅源于重庆市主城区一个监测站,易造成估计结果的不准确;其次,结果可能受居民空调拥有率、社会经济水平等因素影响,出现一定偏倚。

利益冲突 无| [1] Costello A,Abbas M,Allen A,et al. Managing the health effects of climate change:Lancet and University College London Institute for Global Health Commission[J]. Lancet,2009,373(9676):1693-1733. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60935-1. |

| [2] Hajat S,Kosatky T. Heat-related mortality:a review and exploration of heterogeneity[J]. J Epidemiol Commun Health,2010,64(9):753-760. DOI:10.1136/jech.2009.087999. |

| [3] Allen SK,Plattner GK,Nauels A,et al. Climate Change 2013:The Physical Science Basis. An overview of the Working Group 1 Contribution to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change[R]. Vienna,Austria:IPCC,2014. |

| [4] Yang J,Ou CQ,Guo YM,et al. The burden of ambient temperature on years of life lost in Guangzhou,China[J]. Sci Rep,2015,5:12250. DOI:10.1038/srep12250. |

| [5] Wang H,Dwyer-Lindgren L,Lofgren KT,et al. Age-specific and sex-specific mortality in 187 countries,1970-2010:a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010[J]. Lancet,2012,380(9859):2071-2094. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61719-X. |

| [6] 杨军,欧春泉,丁研,等. 分布滞后非线性模型[J]. 中国卫生统计,2012,29(5):772-773,777. Yang J,Ou CQ,Ding Y,et a1. Distributed lag non-linear model[J]. Chin J Health Stat,2012,29(5):772-773,777. |

| [7] Armstrong B. Models for the relationship between ambient temperature and daily mortality[J]. Epidemiology,2006,17(6):624-631. DOI:10.1097/01.ede.0000239732.50999.8f. |

| [8] Braga AL,Zanobetti A,Schwartz J. The effect of weather on respiratory and cardiovascular deaths in 12 U.S. cities[J]. Environ Health Perspect,2002,110(9):859-863. |

| [9] 杨军,欧春泉,丁研,等. 广州市逐日死亡人数与气温关系的时间序列研究[J]. 环境与健康杂志,2012,29(2):136-138. Yang J,Ou CQ,Ding Y,et al. Association between daily temperature and mortality in Guangzhou:a time-series study[J]. J Environ Health,2012,29(2):136-138/a>. |

| [10] Abrignani MG,Corrao S,Biondo GB,et al. Influence of climatic variables on acute myocardial infarction hospital admissions[J]. Int J Cardiol,2009,137(2):123-129. DOI:10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.06.036. |

| [11] Huang CR,Barnett AG,Wang XM,et al. The impact of temperature on years of life lost in Brisbane,Australia[J]. Nat Climate Change,2012,2(4):265-270. DOI:10.1038/nclimate 1369. |

| [12] Huang CR,Barnett AG,Wang XM,et al. Effects of extreme temperatures on years of life lost for cardiovascular deaths:a time series study in Brisbane,Australia[J]. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes,2012,5(5):609-614. DOI:10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.112.965707. |

| [13] Basu R. High ambient temperature and mortality:a review of epidemiologic studies from 2001 to 2008[J]. Environ Health,2009,8(1):40. DOI:10.1186/1476-069X-8-40. |

| [14] Analitis A,Katsouyanni K,Biggeri A,et al. Effects of cold weather on mortality:results from 15 European cities within the PHEWE project[J]. Am J Epidemiol,2008,168(12):1397-1408. DOI:10.1093/aje/kwn266. |

| [15] 李萌萌,周脉耕,张霞,等. 济南市4个区气温对非意外死亡及死因别死亡的影响[J]. 中华流行病学杂志,2014,35(6):684-688. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2014.06.015. Li MM,Zhou MG,Zhang X,et al. Impact of temperature on non-accidental deaths and cause-specific mortality in four districts of Jinan[J]. Chin J Epidemiol,2014,35(6):684-688. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2014.06.015. |

| [16] Egondi T,Kyobutungi C,Rocklöv J. Temperature variation and heat wave and cold spell impacts on years of life lost among the urban poor population of Nairobi,Kenya[J]. Int J Environ Res Public Health,2015,12(3):2735-2748. DOI:10.3390/ijerph120302735. |

| [17] Seeman TE,Singer BH,Ryff CD,et al. Social relationships,gender,and allostatic load across two age cohorts[J]. Psychosom Med,2002,64(3):395-406. DOI:10.1097/00006842-200205 000-00004. |

2016, Vol. 37

2016, Vol. 37