文章信息

- 刘冬静, 王苹, 王竹青, 袁园, 李静, 王科, 吴涛.

- Liu Dongjing, Wang Ping, Wang Zhuqing, Yuan Yuan, Li Jing, Wang Ke, Wu Tao.

- 后GWAS时代非综合征型唇腭裂致病基因的探索——从综合征型到非综合征型

- Exploring pathogenic genes of non-syndromic oral cleft in post-GWAS era: from syndromic oral cleft to non- syndromic oral cleft

- 中华流行病学杂志, 2015, 36(11): 1319-1323

- Chinese Journal of Epidemiology, 2015, 36(11): 1319-1323

- http://dx.doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2015.11.027

-

文章历史

- 投稿日期: 2015-05-28

2. 北京市疾病预防控制中心;

3. 北京大学口腔医院;

4. 青岛大学医学院附属医院

2. Beijing Center for Disease Control and Prevention;

3. Peking University Hospital of Stomatology;

4. The Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University

唇腭裂是一类常见的出生缺陷,活产儿的患病率约为1/700[1]。患儿因口腔颌面部结构异常,致进食、语言、生长发育及心理健康均受影响。唇腭裂按解剖结构可分为单纯腭裂(cleft palate only,CPO)和唇裂合并或不合并腭裂(cleft lip with or without cleft palate,CL/P),通常认为两者具有不同的病因。唇腭裂患病率存在种族和性别差异,亚洲人群患病率为1.52‰[2],高于白种人的1.0‰和非洲人的0.4‰[1];男性和女性CL/P患者的比例约为2 ∶ 1,而在CPO患者中这一比例约为1 ∶ 2[1]。唇腭裂可分为综合征型与非综合征型两类,前者为单基因遗传病,患儿伴有其他系统器官畸形或生长发育异常,目前其致病基因已较明确。而后者为一类多基因影响的复杂疾病,患儿不伴有其他畸形或异常,此类型较之综合征型更为常见,约70%的CL/P患者及50%的CPO患者为非综合征型[3]。中国人群非综合征型唇腭裂(non-syndromic oral cleft,NSOC)的发生率为1.13/1 000~1.30/1 000活产儿,高于其他地区和种族人群[2]。探索该病的病因将为制定有效的预防策略从而降低人群发病风险提供重要依据。

NSOC的发生是遗传与环境因素共同作用的结果,该病致病基因的定位为目前研究的热点与难点。迄今多项大规模全基因组关联研究(Genome-Wide Association Studies,GWAS)为NSOC易感基因的探索提供了高质量的证据,发现并验证了多个候选基因与该病的关联。然而,GWAS从研究设计上强调对全基因组常见遗传变异的覆盖率,并不以检测位点所具备的潜在生物学功能作为选择位点的前提。同时,GWAS发现的信号往往位于DNA序列的非功能区,难以解释其生物学致病机制。既往研究显示,一些综合征型唇腭裂的致病基因同时与NSOC存在关联,如van der Woude综合征的致病基因IRF6与非综合征型唇裂合并或不合并腭裂(non-syndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate,NSCL/P)的关联在多个独立研究中得到了证实[4, 5, 6, 7]。这一定位NSOC致病基因的思路正是在合理的生物学背景下探索遗传危险因素的作用。其理论依据为同一基因能够导致罕见的综合征型(100 000~200 000个活产儿中出现1例)或较常见的非综合征型(500~2 000个活产儿中出现1例)唇腭裂的发生,导致前者发生的突变是罕见而显著有害的,导致后者发生的突变是常见而危害性弱的,两种突变在不同程度上影响了同一基因的功能,从而产生不同程度的疾病表现[8]。本文对已有证据支持其与NSOC相关联的综合征型唇腭裂致病基因进行综述,以探讨这一策略在后GWAS时代筛选非综合征型唇腭裂致病基因中的价值。

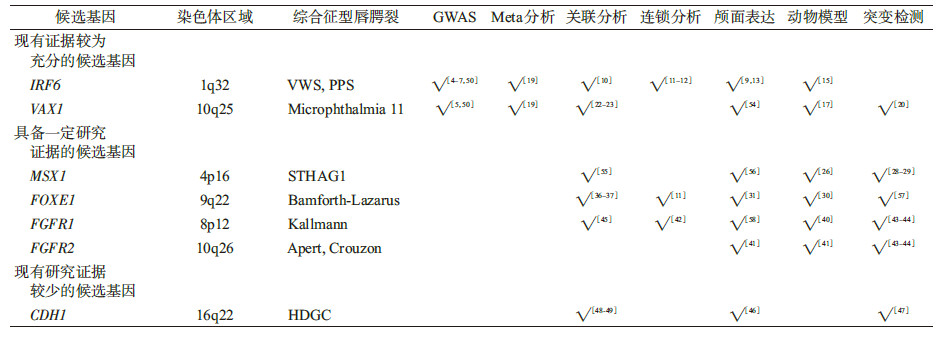

1. 现有证据较为充分的候选基因:此类基因符合以下特征:①现有GWAS研究发现其与NSOC的发病风险显著关联;②有Meta分析证实其阳性关联;③有较高质量的独立候选基因研究重复发现关联;④表达分析、动物模型等研究支持其相关生物学功能。此类候选基因包括IFR6和VAX1。

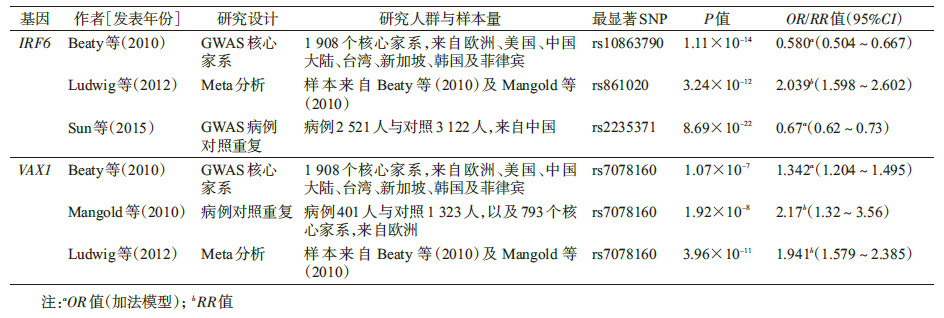

(1)干扰素调节因子6基因(interferon regulatory factor 6,IRF6):IRF6位于染色体1q32.3~1q41区域,其编码产物属于转录因子家族。Kondo等[9]于2002年在北欧人群中发现IRF6基因突变可导致常染色体显性疾病Van der Woude综合征(VWS,OMIM #119300)和腘翼状胬肉综合征(PPS,OMIM #119500),此两种综合征的患者常伴有唇腭裂的表型。2004年,Zucchero等[10]首次发现IRF6基因多态性与NSOC的发生存在显著关联。Zucchero等对来自全球10个人群的1 986个唇腭裂家系进行研究,结果显示rs642961位点与NSCL/P存在关联,且这一关联在之后的全基因组连锁分析中得到验证[11, 12]。rs642961位于IRF6上游的增强子内,对其致病生物学机制的研究发现,突变可以影响IRF6上转录因子AP-2a的结合位点[13],而AP-2a对颅面正常发育必不可少[14]。此后,IRF6多态性与NSCL/P的关联在多个候选基因关联研究、GWAS[4, 5, 6, 7]及对GWAS结果在不同人群已研究得到进一步证实,动物模型和表达分析等也支持IRF6与唇腭裂存在生物学关联[15, 16]。表 1总结了相关GWAS研究与Meta分析的结果。IRF6是运用“从综合征型到非综合征型唇腭裂”这一研究思路比较成功的范例。

(2)腹前同源盒基因1(ventral anterior homeobox 1,VAX1):VAX1位于染色体10q25-26区域,编码转录调节因子,参与视觉神经系统发育。此基因在颅面部结构有广泛的表达。动物实验表明,vax1基因纯合突变的小鼠出现包括腭裂在内的颅面部异常[17]。近年来发现,VAX1突变可能导致人类Microphthal-mia综合征(OMIM等#614402),该病患者主要表现为无眼或小眼畸形,可伴有双侧唇腭裂[18]。VAX1基因与NSCL/P的关联最早由Mangold等[5]在欧洲人群中开展的GWAS发现,该基因附近的rs7078160和rs4752028得到了全基因组水平显著的结果,并在独立家系样本中得以验证。2012年Ludwig等[19]的Meta分析也重复了这一结果(表 2)。同年一项对德国人群NSCL/P的测序研究筛选出17个VAX1突变,其频率在病例和对照中无显著差异,但提示VAX1的长转录异构体可能参与疾病发生[20]。还有研究发现其可能通过亲源效应影响NSCL/P的风险[21]。此外,在欧洲、中非、东南亚等不同人种开展的多个独立研究也重复发现了VAX1多态性与NSCL/P的关联[22, 23]。

迄今为止,GWAS研究、候选基因关联研究、连锁分析、动物模型和表达分析等多方面的证据已证实IRF6与非综合征型唇腭裂的发生相关联,而VAX1也已有较可靠的证据,进一步定位致病位点、阐明致病生物学机制等是未来的研究热点。

2. 具备一定研究证据的候选基因:现有若干较高质量的独立候选基因研究发现这类综合征型唇腭裂的致病基因同时与NSOC具有显著关联,并获得表达分析、动物模型等功能分析支持,但尚无来自GWAS的研究证据。相关基因包括MSX1、FOXE1、FGFR1及FGFR2。

(1)肌节同源盒基因1(muscle segment homoebox gene1,MSX1):MSX1位于染色体4p16区域,序列高度保守,其编码的转录因子与四肢形成和颅面部发育密切相关。20世纪90年代,研究者发现MSX1突变引起人类选择性牙齿发育不全,伴或不伴有唇腭裂(selective tooth agenesis with or without cleft,STHAG1,OMIM #106600),此异常为孟德尔遗传病[24, 25]。msx1缺陷型的小鼠表现出一系列颌面部异常[26]。国内外对MSX1基因的生物学功能已有一定研究,对MSX1的表达、功能以及与其他分子的相互作用已经提出了一些可能的机制。最近有研究利用生物信息技术初步描绘了以MSX1为中心的基因网络,并阐述了MSX1与IFR6、SUMO1、BMP4、FGFR等多个NSCL/P候选基因在网络中的相互作用[27]。目前,MSX1多态性与NSCL/P的关联尚未明确。在候选基因时代,虽然在多个人群中观察到MSX1与NSCL/P存在显著关联,但研究结果并不一致。2009年起开展的几项GWAS没有在MSX1基因区域得到显著的信号。另外,有研究表明MSX1罕见变异能够增加NSCL/P的发生风险。MSX1全基因测序显示,2%的NSCL/P患者存在该基因的突变[28]。截至2013年至少已有位于25个NSCL/P候选基因的68个罕见突变通过测序被发现,Leslie和Murray[29]将这些突变与正常对照的基因序列进行比对,并预测突变的性质,研究结果有力的支持了MSX1罕见变异与NSCL/P发生的关联。

(2)FOXE1:位于染色体9q22区域,其编码产物是叉头框(fork-head box,FOX)转录因子家族的成员。已有动物模型和表达分析证据支持FOXE1在唇和腭发育中的作用[30, 31]。Bamforth等[32]最早描述了Bamforth- Lazarus (OMIM #241850)综合征的临床表现,包括无甲状腺、腭裂、后鼻孔闭锁等临床特征,其后Clifton-Bligh等[33]发现这一异常与FOXE1突变相关。2004年一项对13个NSOC全基因组连锁分析进行的Meta分析首次将染色体9q21区域列入非综合征型唇腭裂候选区域,这一区域得到了全基因组水平显著的结果(HLOD=6.6)[11]。之后多个对9q21区域易感基因的精细定位证据指向FOXE1[34, 35]。2013年Beaty等[7]利用1 108个NSCL/P核心家系对该课题组2010年发表的GWAS结果进行验证,位于FOXE1的 rs6478391得到临近显著的结果。FOXE1多态性与NSCL/P的关联在多个人群中被观察到[36, 37],也陆续有罕见变异在NSCL/P患者中被筛选出,但不同研究也常有不一致的结果。对非综合征型腭裂(non-syndromic cleft palate only,NSCPO)的研究常因样本量不足而难以发现真实的效应,不过目前一些证据支持FOXE1是NSCL/P和NSCPO共有的候选基因。目前对FOXE1突变致病的生物学机制已有初步的探究,如Venza等[38]发现位于基因启动子的C(-1204)G纯合突变可能通过影响转录因子MYF-5(生肌决定因子)与启动子的结合来抑制FOXE1的转录,从而影响唇腭的正常发育。对其下游基因的研究发现,FOXE1蛋白可在转录与翻译水平调节唇裂候选基因MSX1和TGF-β 3的表达[39]。

(3)FGFR1和FGFR2:成纤维细胞生长因子受体基因(fibroblast growth factor receptor genes)是一个多基因家族,成员同属酪氨酸激酶受体基因。其所参与的FGF信号通路介导细胞增殖、迁移和分化等过程,与多条其他信号通路交织形成信号网络,共同协调胚胎发育的各个环节。已有多项表达分析、动物模型等研究描述FGF信号通路在腭发育中的作用[40, 41]。FGFR家族基因突变可引起多种人类发育紊乱性遗传病,其中与FGFR1异常相关的Kallmann综合征(OMIM #147950)及由FGFR2突变引起的Apert综合征(OMIM #101200)和Crouzon综合征(OMIM #123500)的患者均可出现唇腭裂的表型。2007年Riley等[42]开展的全基因组连锁分析首次将染色体8p11-23列入NSCL/P候选区域,在进一步的精细定位中FGFR1得到了最显著的结果。其后Riley等[43, 44]对FGF信号通路基因的外显子和保守非编码区进行测序,并结合生物学功能筛选出多个潜在致病突变,如FGFR1无义突变R609X、FGFR2错义突变D138N等。2013年Leslie和Murray[29]将NSCL/P患者携带的突变与正常对照的基因序列进行比对,结果支持FGFR1和FGFR2罕见变异与NSCL/P的发生相关联。FGFR基因多态性与NSCL/P的关联研究在多个人群中得到了有统计学意义的结果,如最近一项在亚洲和马里兰人群中开展的研究发现,FGFR1在NSCL/P核心家系中存在传递不平衡现象,FGFR2与母亲孕期吸烟及补充维生素存在交互作用[45]。

目前,国内外多项研究为上述基因的表达、功能及调控提出了一系列可能的机制。然而,这些基因与NSOC的关联关系仍缺乏高质量的人群研究证据,例如来自GWAS和Meta分析的证据,未来尚需进一步探索以更好地诠释其在非综合征型唇腭裂发生中的作用。

3. 现有研究证据较少的候选基因:这类基因仅有小样本量的人群研究证据提示其与NSOC发生的关系,且来自表达分析、动物模型和突变检测等方面的研究结果尚不足以说明问题。此类基因包括钙黏素1基因(cadherin 1,CDH1)TP63、TBX22和PVRL1等。CDH1位于染色体16q22.1区域,其编码产物E钙黏蛋白主要介导上皮细胞胞间黏附过程,对维持正常的组织形态和细胞分化起重要作用。CDH1表达异常与多种癌症相关,包括遗传性弥漫型胃癌、子宫内膜癌、卵巢癌等。Frebourg等[46]于2006年首次描述了CDH1胚系突变与综合征型唇腭裂的关联。此后其他研究相继报道了多个携带CDH1突变的此种综合征型唇腭裂病例。2012年,Vogelaar等[47]对81名NSOC患者进行CDH1编码区域的测序及功能分析,筛选出3个潜在的功能性错义突变。目前已有研究在波兰[48]、中国汉族[49]人群中观察到CDH1和NSOC存在关联,但总体来说相关研究尚较少,且因样本量不足、病因异质性等原因没有得出较一致的结果。其他现有研究证据较少的NSOC候选基因包括TP63(tumor protein p63)、TBX22(T-Box 22)及PVRL1(poliovirus receptor-related 1)等,对于这些基因的研究往往样本量小,研究结果相互不一致,难以推断其与NSOC的关系,相关研究仍有待开展。

最近Sun等[50]在中国人群中开展的一项GWAS通过三阶段的病例对照设计再次验证了IRF6和VAX1与NSCL/P的关联,同时,此项GWAS还发现了与中国人群疾病发生相关的新的候选区域:染色体16p13.3。此区域最显著的位点 rs8049367(p=8.98×10-12)位于CREBBP基因上游,ADCY9基因下游,而这一区域的缺失在既往研究中被发现与Rubinstein-Taybi综合征的发生相关[51, 52],此综合征的表型谱包含唇腭裂[53]。研究者进一步对候选基因进行表达分析,发现相对于在非患者干细胞培养物中的表达水平,ADCY9在NSCL/P患者牙髓干细胞中的表达显著上调。16p13.3这一新的NSCL/P候选区域首次被发现,有待于进一步的重复。

本文详述的基因中,IRF6、VAX1属于与NSOC关联较为明确的候选基因,其余基因证据仍不充分(表 2)。如前所述,多数基因尚未得到较一致的研究结果,其原因可能为样本量不足导致研究设计的把握度不足、疾病本身的复杂性与异质性等。另外,由于表型的相似或重叠,综合征型与非综合征型唇腭裂有时难以区分。部分唇腭裂表型可能是某综合征表型谱中的一部分,患者因病症较轻等原因没有报告其他异常,易被错误归类为非综合征型,由此对NSOC致病基因的正确鉴定产生一定的影响。

复杂疾病的病因学研究不仅需要从统计学意义上发现疾病相关基因,更要揭示基因突变如何参与疾病发生的生物学机制。即便是人群关联证据比较明确的候选基因,仍需继续定位致病位点、阐明生物学致病机制。从综合征型唇腭裂致病基因入手来寻找NSOC致病基因的思路有其合理性及价值,在后GWAS时代应充分利用这一研究策略,结合基因的生物学功能深入探索NSOC遗传危险因素,以期为唇腭裂的产前咨询、出生缺陷的有效防治提供有力的科学保障。

| [1] Dixon MJ,Marazita ML,Beaty TH,et al. Cleft lip and palate: synthesizing genetic and environmental influences[J]. Nat Rev Genet,2011,12(3):167-178. |

| [2] Cooper ME,Ratay JS,Marazita ML. Asian oral-facial cleft birth prevalence[J]. Cleft Palate Craniofac J,2006,43(5):580-589. |

| [3] Shi M,Wehby GL,Murray JC. Review on genetic variants and maternal smoking in the etiology of oral clefts and other birth defects[J]. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today,2008,84(1):16-29. |

| [4] Birnbaum S,Ludwig KU,Reutter H,et al. Key susceptibility locus for nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate on chromosome 8q24[J]. Nat Genet,2009,41(4):473-477. |

| [5] Mangold E,Ludwig KU,Birnbaum S,et al. Genome-wide association study identifies two susceptibility loci for nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate[J]. Nat Genet,2009,42(1):24-26. |

| [6] Beaty TH,Murray JC,Marazita ML,et al. A genome-wide association study of cleft lip with and without cleft palate identifies risk variants near MAFB and ABCA4[J]. Nat Genet,2010,42(6):525-529. |

| [7] Beaty TH,Taub MA,Scott AF,et al. Confirming genes influencing risk to cleft lip with/without cleft palate in a case-parent trio study[J]. Hum Genet,2013,132(7):771-781. |

| [8] Vieira AR. Unraveling human cleft lip and palate research[J]. J Dent Res,2008,87(2):119-125. |

| [9] Kondo S,Schutte BC,Richardson RJ,et al. Mutations in IRF6 cause Van der Woude and popliteal pterygium syndromes[J]. Nat Genet,2002,32(2):285-289. |

| [10] Zucchero TM,Cooper ME,Maher BS,et al. Interferon regulatory factor 6(IRF6) gene variants and the risk of isolated cleft lip or palate[J]. N Engl J Med,2004,351(8):769-780. |

| [11] Marazita ML,Murray JC,Lidral AC,et al. Meta-analysis of 13 genome scans reveals multiple cleft lip/palate genes with novel loci on 9q21 and 2q32-35[J]. Am J Hum Genet,2004,75(2):161-173. |

| [12] Marazita ML,Lidral AC,Murray JC,et al. Genome scan,fine-mapping,and candidate gene analysis of non-syndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate reveals phenotype-specific differences in linkage and association results[J]. Hum Hered,2009,68(3):151-170. |

| [13] Rahimov F,Marazita ML,Visel A,et al. Disruption of an AP-2α binding site in an IRF6 enhancer is associated with cleft lip[J]. Nat Genet,2008,40(11):1341-1347. |

| [14] Milunsky JM,Maher TA,Zhao G,et al. TFAP2A mutations result in branchio-oculo-facial syndrome[J]. Am J Hum Genet,2008,82(5):1171-1177. |

| [15] Richardson RJ,Dixon J,Malhotra S,et al. Irf6 is a key determinant of the keratinocyte proliferation-differentiation switch[J]. Nat Genet,2006,38(11):1329-1334. |

| [16] Iwata J,Suzuki A,Pelikan RC,et al. Smad4-Irf6 genetic interaction and TGF β-mediated IRF6 signaling cascade are crucial for palatal fusion in mice[J]. Development,2013,140(6):1220-1230. |

| [17] Hallonet M,Hollemann T,Pieler T,et al. Vax1,a novel homeobox-containing gene,directs development of the basal forebrain and visual system[J]. Genes Dev,1999,13(23):3106-3114. |

| [18] Slavotinek AM,Chao R,Vacik T,et al. VAX1 mutation associated with microphthalmia,corpus callosum agenesis,and orofacial clefting:the first description of a VAX1 phenotype in humans[J]. Hum Mutat,2012,33(2):364-368. |

| [19] Ludwig KU,Mangold E,Herms S,et al. Genome-wide meta- analyses of nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate identify six new risk loci[J]. Nat Genet,2012,44(9):968-971. |

| [20] Nasser E,Mangold E,Tradowsky DC,et al. Resequencing of VAX1 in patients with nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate[J]. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol,2012,94(11):925-933. |

| [21] Butali A,Suzuki S,Cooper ME,et al. Replication of genome wide association identified candidate genes confirm the role of common and rare variants in PAX7 and VAX1 in the etiology of nonsyndromic CL(P)[J]. Am J Med Genet A,2013,161(5):965-972. |

| [22] Mostowska A,Hozyasz KK,Wojcicka K,et al. Polymorphic variants at 10q25.3 and 17q22 loci and the risk of non-syndromic cleft lip and palate in the polish population[J]. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol,2012,94(1):42-46. |

| [23] Figueiredo JC,Ly S,Raimondi H,et al. Genetic risk factors for orofacial clefts in Central Africans and Southeast Asians[J]. Am J Med Genet A,2014,164(10):2572-2580. |

| [24] van den Boogaard MJ,Dorland M,Beemer FA,et al. MSX1 mutation is associated with orofacial clefting and tooth agenesis in humans[J]. Nat Genet,2000,24(4):342-343. |

| [25] Lidral AC,Reising BC. The role of MSX1 in human tooth agenesis[J]. J Dent Res,2002,81(4):274-278. |

| [26] Satokata I,Maas R. Msx1 deficient mice exhibited cleft palate and abnormalities of craniofacial and tooth development[J]. Nat Genet,1994,6(4):348-356. |

| [27] Dai JW,Mou ZF,Shen SY,et al. Bioinformatic analysis of Msx1 and Msx2 involved in craniofacial development[J]. J Craniofac Surg,2014,25(1):129-134. |

| [28] Jezewski PA,Vieira AR,Nishimura C,et al. Complete sequencing shows a role for MSX1 in non-syndromic cleft lip and palate[J]. J Med Genet,2003,40(6):399-407. |

| [29] Leslie EJ,Murray JC. Evaluating rare coding variants as contributing causes to non-syndromic cleft lip and palate[J]. Clin Genet,2013,84(5):496-500. |

| [30] De Felice M,Ovitt C,Biffali E,et al. A mouse model for hereditary thyroid dysgenesis and cleft palate[J]. Nat Genet,1998,19(4):395-398. |

| [31] Trueba SS,Augé J,Mattei G,et al. PAX8,TITF1,and FOXE1 gene expression patterns during human development:new insights into human thyroid development and thyroid dysgenesis-associated malformations[J]. J Clin Endocrinol Metab,2005,90(1):455-462. |

| [32] Bamforth JS,Hughes IA,Lazarus JH,et al. Congenital hypothyroidism,spiky hair,and cleft palate[J]. J Med Genet,1989,26(1):49-51. |

| [33] Clifton-Bligh RJ,Wentworth JM,Heinz P,et al. Mutation of the gene encoding human TTF-2 associated with thyroid agenesis,cleft palate and choanal atresia[J]. Nat Genet,1998,19(4):399-401. |

| [34] Letra A,Menezes R,Govil M,et al. Follow-Up Association Studies of Chromosome Region 9q and Nonsyndromic Cleft Lip/Palate[J]. Am J Med Genet A,2010,152A(7):1701-1710. |

| [35] Moreno LM,Mansilla MA,Bullard SA,et al. FOXE1 association with both isolated cleft lip with or without cleft palate,and isolated cleft palate[J]. Hum Mol Genet,2009,18(24):4879-4896. |

| [36] Aldhorae KA,Boehmer AC,Ludwig KU,et al. Nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate in arab populations:genetic analysis of 15 risk loci in a novel case-control sample recruited in Yemen[J]. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol,2014,100(4):307-313. |

| [37] Nikopensius T,Kempa I,Ambrozaityte L,et al. Variation in FGF1,FOXE1,and TIMP2 genes is associated with nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate[J]. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol,2011,91(4):218-225. |

| [38] Venza M,Visalli M,Venza I,et al. Altered binding of MYF-5 to FOXE1 promoter in non-syndromic and CHARGE-associated cleft palate[J]. J Oral Pathol Med,2009,38(1):18-23. |

| [39] Venza I,Visalli M,Parrillo L,et al. MSX1 and TGF-beta 3 are novel target genes functionally regulated by FOXE1[J]. Hum Mol Genet,2011,20(5):1016-1025. |

| [40] Wang C,Chang JYF,Yang C,et al. Type 1 fibroblast growth factor receptor in cranial neural crest cell-derived mesenchyme is required for palatogenesis[J]. J Biol Chem,2013,288(30):22174-22183. |

| [41] Rice R,Spencer-Dene B,Connor EC,et al. Disruption of Fgf10/Fgfr2b-coordinated epithelial-mesenchymal interactions causes cleft palate[J]. J Clin Invest,2004,113(12):1692-1700. |

| [42] Riley BM,Schultz RE,Cooper ME,et al. A genome-wide linkage scan for cleft lip and cleft palate identifies a novel locus on 8p11-23[J]. Am J Med Genet A,2007,143(8):846-852. |

| [43] Riley BM,Murray JC. Sequence evaluation of FGF and FGFR gene conserved non-coding elements in non-syndromic cleft lip and palate cases[J]. Am J Med Genet A,2007,143(24):3228- 3234. |

| [44] Riley BM,Mansilla MA,Ma J,et al. Impaired FGF signaling contributes to cleft lip and palate[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA,2007,104(11):4512-4517. |

| [45] Wang H,Zhang TX,Wu T,et al. The FGF and FGFR gene family and risk of cleft lip with or without cleft palate[J]. Cleft Palate Craniofac J,2013,50(1):96-103. |

| [46] Frebourg T,Oliveira C,Hochain P,et al. Cleft lip/palate and CDH1/E-cadherin mutations in families with hereditary diffuse gastric cancer[J]. J Med Genet,2006,43(2):138-142. |

| [47] Vogelaar IP,Figueiredo J,van Rooij IA,et al. Identification of germline mutations in the cancer predisposing gene CDH1 in patients with orofacial clefts[J]. Hum Mol Genet,2013,22(5):919-926. |

| [48] Hozyasz KK,Mostowska A,Wojcicki P,et al. Nucleotide variants of the cancer predisposing gene CDH1 and the risk of non-syndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate[J]. Fam Cancer,2014,13(3):415-421. |

| [49] Song YB,Zhang SY. Association of CDH1 promoter polymorphism and the risk of non-syndromic orofacial clefts in a Chinese Han population[J]. Arch Oral Biol,2011,56(1):68-72. |

| [50] Sun YM,Huang YQ,Yin AH,et al. Genome-wide association study identifies a new susceptibility locus for cleft lip with or without a cleft palate[J]. Nat Commun,2015,6:6414. |

| [51] Lai AH,Brett MS,Chin WH,et al. A submicroscopic deletion involving part of the CREBBP gene detected by array-CGH in a patient with Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome[J]. Gene,2012,499(1):182-185. |

| [52] Kim SR,Kim HJ,Kim YJ,et al. Cryptic microdeletion of the CREBBP gene from t(1; 16) (p36.2; p13.3) as a novel genetic defect causing Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome[J]. Ann Clin Lab Sci,2013,43(4):450-456. |

| [53] Hennekam RC,van Doorne JM. Oral aspects of Rubinstein- Taybi syndrome[J]. Am J Med Genet Suppl,1990,6:42-47. |

| [54] Soria JM,Taglialatela P,Gil-Perotin S,et al. Defective postnatal neurogenesis and disorganization of the rostral migratory stream in absence of the Vax1 homeobox gene[J]. J Neurosci,2004,24(49):11171-11181. |

| [55] Ma L,Xu M,Li D,et al. A miRNA-binding-site SNP of MSX1 is associated with NSOC susceptibility[J]. J Dent Res,2014,93(6):559-564. |

| [56] Yang GB,Yuan GH,Ye WD,et al. An atypical canonical bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling pathway regulates Msh homeobox 1 (Msx1) expression during odontogenesis[J]. J Biol Chem,2014,289(45):31492-31502. |

| [57] Srichomthong C,Ittiwut R,Siriwan P,et al. FOXE1 mutations in Thai patients with oral clefts[J]. Genet Res,2013,95(5):133-137. |

| [58] Peters KG,Werner S,Chen G,et al. Two FGF receptor genes are differentially expressed in epithelial and mesenchymal tissues during limb formation and organogenesis in the mouse[J]. Development,1992,114(1):233-243. |

2015, Vol. 36

2015, Vol. 36