文章信息

- 黎健, 潘浩, 肖文佳, 胡家瑜, 袁政安.

- Li Jian, Pan Hao, Xiao Wenjia, Hu Jiayu, Yuan Zheng'an.

- 上海市2010-2014年确认和疑似诺如病毒感染聚集性疫情流行病学分析

- Epidemiology of confirmed and suspected norovirus outbreaks in Shanghai, 2010-2014

- 中华流行病学杂志, 2015, 36(11): 1249-1252

- Chinese Journal of Epidemiology, 2015, 36(11): 1249-1252

- http://dx.doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2015.11.013

-

文章历史

- 投稿日期: 2015-03-06

诺如病毒(NoV)是致人类腹泻的重要病原[1]。由于NoV具有传播途径多,感染剂量低,缺乏持续免疫力,人群普遍易感等特点,成为全球散发性非细菌性胃肠炎及急性非细菌性胃肠炎聚集性疫情的首要原因[2],美国95%的急性非细菌性胃肠炎暴发是由NoV引起[3]。近年来我国NoV所致的急性胃肠炎聚集性疫情也呈逐渐升高的趋势。为此本文分析上海市2010年1月至2014年11月NoV聚集性疫情的发病状况和流行病学特征。

资料与方法1.数据资料:源自2010年1月至2014年11月上海市各区县发生的疑似或确认NoV聚集性疫情调查报告。聚集性疫情定义为学校、幼儿园、养老院等集体单位内同一班级或同一宿舍,1 d内发生≥3例,或连续3 d内发生>5例,以呕吐和/或腹泻为主要症状的病例。确认聚集性疫情为病例吐泻物、食品或饮水等样本中检出NoV的疫情;疑似聚集性疫情为病例有呕吐、腹泻等NoV感染的主要临床表现,且疫情发生在NoV感染高发的秋冬季,但样本中未检出NoV的疫情。

2.病原学检测:应用实时荧光定量反转录聚合酶链反应检测NoV核酸(采用上海之江生物科技股份有限公司试剂盒)。

3.统计学分析:以Excel软件双录入建立数据库,逻辑校对后导入SPSS 16.0软件分析。计数资料采用χ2检验或Fisher精确概率法检验,结果判定P值取双侧概率,检验水准α取值为0.05。

结果1.一般情况:2010年1月至2014年11月上海市NoV聚集性疫情呈逐渐增加趋势。此期间报告疑似或确认NoV聚集性疫情共80起,其中确认疫情59起(73.75%),疑似疫情21起(26.25%)。共报告感染病例2 399例,总罹患率为4.17%。罹患人数M=18(5~278)例/起。各起疫情的罹患人数主要为10~50例,其中32起(40.00%)为10~20例/起,27起(33.75%)为21~50例/起。

2.疫情持续时间及峰值时间:此期间疫情持续时间M=4.5(1~20) d。其中疫情持续时间 < 5 d有40起(50.00%),5~9 d有28起(35.00%),≥10 d有12起(15.00%)。疫情达到峰值时间M=2(0~12) d。其中疫情峰值 < 2 d有52起(65.00%),3~4及≥5 d的分别有17起(21.25%)和11起(13.75%)。

3. 聚集性疫情的分布特征:

(1)季节分布:秋冬季为高发季节,其中10、11和12月各报告8、19和12起,1和2月各报告8和6起,该5个月疫情总起数占总数的66.25%;夏季少有发生,6-9月共报告3起(3.75%)。

(2)地点分布:疫情主要发生在学校(小学、中学和九年一贯制学校)、幼儿园和养老院,共发生75起(93.75%)。其中小学、中学和一贯制学校分别发生26、10和7起,三者之和占总起数的53.75%;幼儿园和养老院各发生19和13起,各占总数的23.75%和16.25%。此外医院和社区分别发生3和2起。从疫情涉及的班级、宿舍或病房数量分析,有24起疫情发生在幼儿园和学校1个班级内,占幼儿园和学校疫情总数的38.71%,其他38起疫情均扩散至≥2个的班级;而16起发生在养老院和医院的疫情均蔓延扩散至≥2个宿舍或病房,二者间的差异有统计学意义(Fisher's检验,P=0.002)。

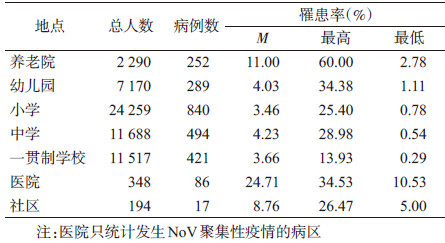

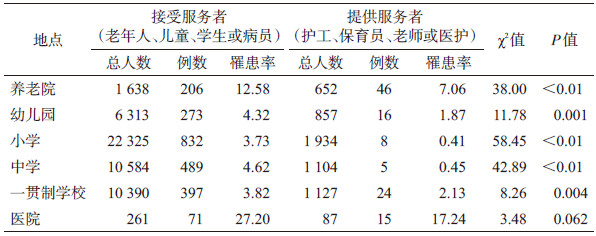

(3)人群分布:学生、托幼儿童及养老院老年人发病例数最多,分别为1 755、289及252例,占总病例数的73.16%、12.05%及10.50%。分析罹患率(表 1),医院住院病例和养老院老年人平均罹患率较高,分别为24.71%和11.00%;而托幼儿童及学生的平均罹患率较低,均 < 5%。各类机构人群平均罹患率的差异有统计学意义(χ2=683.12,P < 0.01)。各集体机构的员工(护工、保育员、老师或医护人员)均有一定发病。其中提供服务者罹患率均低于接受服务者的罹患率(表 2)。除医院外,其他机构的提供服务者和接受服务者的罹患率差异均有统计学意义(P < 0.01)。

4.主要临床特征:分析2 399例病例显示以呕吐为主要的临床症状,共有1 900例(79.20%),平均呕吐7.53次;腹泻694例(28.93%),平均腹泻7.31次;发热364例(15.17%)。3项临床症状例数间的差异有统计学意义(χ2=2 251.48,P < 0.01)。

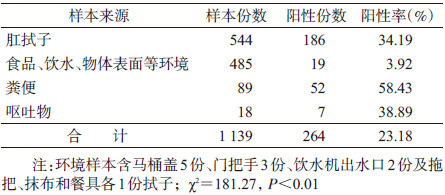

5.实验室检测:对77起确认或疑似疫情采集各类标本1 603份,检出NoV阳性299份,阳性率为18.65%。有54起疫情采集的标本可细分种类,实验室检测结果显示(表 3),1 139份各类标本中,病例生物样本阳性检出率较高,其中粪便阳性率最高(58.43%),其次为呕吐物(38.89%)和肛拭子(34.19%);食品、饮水、物体表面涂抹拭子等环境样本的阳性率较低,仅3.92%。

6.暴露来源:分析NoV聚集性疫情的流行曲线,并结合疫情持续时间(M=4.5 d)及疫情达到峰值时间(M=2 d),判定2010年1月至2014年11月上海市NoV聚集性疫情的暴露形式主要为短期共同来源(图 1中A、B),其中40起(50%)为短期共同来源暴露,流行曲线主要为单峰型分布,表现为首发病例出现后,在2~3 d内流行达到高峰,然后疫情逐渐平息,持续时间一般不超过5 d。12起疫情(15%)呈连续蔓延传播形式(图 1中C、D),病例较多,流行时间>10 d,呈现不止一个流行高峰,出现了二代甚至三代病例。

|

| 图 1 上海市NoV聚集性疫情流行形式 |

7.主要传播途径:2010年1月至2014年11月上海市NoV聚集性疫情的主要传播途径为接触传播,表现为潜伏期病例或已出现症状但未隔离的病例继续与健康人群发生密切接触而形成"病例-健康人"的疫情扩散,此类途径传播包括18起幼儿园托幼儿童、35起学校学生、10起养老院老年人和2起医院病例的疫情,共占疫情总起数的81.25%;其次,集体机构员工作为中介而形成"病例-员工-健康人的传播链也不容忽视,此类途径传播包括2起幼儿园保育员、14起养老院护工、2起医院医生、各1起学校老师和保洁员传播的疫情(均检出NoV);此外,也时有发生间接接触传播,有10起疫情(12.5%)是在物体(门把手、马桶盖、抹布)表面涂抹拭子中检出NoV。虽然所有食品和饮水样本检测结果均为阴性,但有5起疫情是自食堂从业人员肛拭子中检出NoV,2起疫情自饮水机出水口检出NoV,共占疫情总数的8.75%,说明"粪-口"也是传播途径之一。

讨论上海市近年来越来越多的证据显示NoV感染聚集性疫情呈逐年增加趋势,且是引起急性胃肠炎聚集性疫情的重要病原[4, 5, 6, 7, 8]。NoV聚集性疫情具有较明显的季节性高发规律,温带地区秋冬季为高发季节[9, 10],但夏季也出现小高峰[11, 12]。本研究表明2010-2014年上海市NoV聚集性疫情有66.25%发生在秋冬季,呈明显的秋冬季高峰,未出现夏季小高峰。

本文分析显示NoV聚集性疫情高发地点为学校、幼儿园和养老院等相对封闭的集体机构,主要是由病例和健康人之间的密切接触引起的人-人传播。而集体机构的服务提供者也有一定比例的发病,说明在其照顾、护理或治疗病例中将NoV传染给其他健康人,因此集体机构员工对NoV聚集性疫情的扩散风险应该引起重视。本文中接受服务者的罹患率多高于提供服务者,与美国的报道一致[10]。可能的原因:提供服务者的手部卫生情况较好,长期在易暴露于NoV的集体机构中获得较高的免疫力,而不愿意报告疾病也是可能原因之一[13, 14]。本文分析表明经食物或饮水等"粪-口"途径引起的传播虽然相对较少,但其风险不容忽视[15]。有研究报道二次供水系统污染导致NoV聚集性疫情[16],本文中2起疫情是自饮水机出水口检出NoV。且在马桶盖、门把手等物体表面样本中检出NoV,提示应重视间接接触传播对于疫情扩散的公共卫生意义。上海市NoV聚集性疫情主要为短期共同来源暴露,表现为单峰型的流行曲线,持续时间一般不超过5 d。其他相关研究也证实共同来源暴露在集体机构NoV聚集性疫情中较为多见[17, 18]。

综上所述,NoV是引起上海市急性胃肠炎聚集性疫情的主要病原之一,且呈明显的秋冬季高峰,因此应进一步完善NoV聚集性疫情监测,特别是在高发季节对高发场所加强监测,以便有效控制疫情及防止疫情扩散蔓延。

| [1] Kapikian AZ, Wyatt RG, Dolin R, et al. Visualization by immune electron microscopy of a 27-nm particle associated with acute infectious nonbacterial gastroenteritis[J]. J Virol, 1972, 10(5):1075-1081. |

| [2] Patel MM, Widdowson MA, Glass RI, et al. Systematic literature review of role of noroviruses in sporadic gastroenteritis[J]. Emerg Infect Dis, 2008, 14(8):1224-1231. |

| [3] Mead PS, Slutsker L, Dietz V, et al. Food-related illness and death in the United States[J]. Emerg Infect Dis, 1999, 5(5):607-625. |

| [4] Jin M, Sun JL, Chang ZR, et al. Outbreaks of noroviral gastroenteritis and their molecular characteristics in China, 2006-2007[J]. Chin J Epidemiol, 2010, 31(5):549-553. (in Chinese) 靳淼, 孙军玲, 常昭瑞, 等. 中国2006-2007年诺如病毒胃肠炎暴发及其病原学特征分析[J]. 中华流行病学杂志, 2010, 31(5):549-553. |

| [5] Tu ET, Bull RA, Greening GE, et al. Epidemics of gastroenteritis during 2006 were associated with the spread of norovirus GⅡ.4 variants 2006a and 2006b[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2008, 46(3):413-420. |

| [6] Buesa J, Collado B, López-Andújar P, et al. Molecular epidemiology of caliciviruses causing outbreaks and sporadic cases of acute gastroenteritis in Spain[J]. J Clin Microbiol, 2002, 40(8):2854-2859. |

| [7] Lau CS, Wong DA, Tong LK, et al. High rate and changing molecular epidemiology pattern of norovirus infections in sporadic cases and outbreaks of gastroenteritis in Hong Kong[J]. J Med Virol, 2004, 73(1):113-117. |

| [8] Medici MC, Martinelli M, Abelli LA, et al. Molecular epidemiology of norovirus infections in sporadic cases of viral gastroenteritis among children in Northern Italy[J]. J Med Virol, 2006, 78(11):1486-1492. |

| [9] Bernard H, Höhne M, Niendorf S, et al. Epidemiology of norovirus gastroenteritis in Germany 2001-2009:eight seasons of routine surveillance[J]. Epidemiol Infect, 2014, 142(1):63-74. |

| [10] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Outbreaks of acute gastroenteritis transmitted by person-to-person contact-United States, 2009-2010[J]. MMWR Surveill Summ, 2012, 61(9):1-12. |

| [11] Lopman BA, Reacher M, Gallimore C, et al. A summertime peak of “winter vomiting disease”:surveillance of norovirus in England and Wales, 1995 to 2002[J]. BMC Public Health, 2003, 3:13. |

| [12] Lopman B, Vennema H, Kohli E, et al. Increase in viral gastroenteritis outbreaks in Europe and epidemic spread of new norovirus variant[J]. Lancet, 2004, 363(9410):682-688. |

| [13] Lindesmith L, Moe C, Marionneau S, et al. Human susceptibility and resistance to Norwalk virus infection[J]. Nat Med, 2003, 9(5):548-553. |

| [14] Boxman IL, Verhoef L, Dijkman R, et al. Year-round prevalence of norovirus in the environment of catering companies without a recently reported outbreak of gastroenteritis[J]. Appl Environ Microbiol, 2011, 77(9):2968-2974. |

| [15] Loury P, Le Guyader FS, Le Saux JC, et al. A norovirus oyster-related outbreak in a nursing home in France, January 2012[J]. Epidemiol Infect, 2015, 143(12):2486-2493. |

| [16] Li Y, Guo HX, Xu ZH, et al. An outbreak of norovirus gastroenteritis associated with a secondary water supply system in a factory in south China[J]. BMC Public Health, 2013, 13:283. |

| [17] Ding H, Deng J, Xie L, et al. Survey of outbreak of infectious diarrhea caused by norovirus typeⅠin seven schools[J]. Dis Surveill, 2010, 25(4):279-281. (in Chinese) 丁华, 邓晶, 谢立, 等. 一起涉及7所学校的Ⅰ型诺如病毒感染性腹泻暴发调查[J]. 疾病监测, 2010, 25(4):279-281. |

| [18] Wen D, Gu CY, Zu RQ, et al. An outbreak of norovirus gastroenteritis in a primary school[J]. Jiangsu J Prev Med, 2012, 23(5):4-7. (in Chinese) 闻栋, 顾朝阳, 祖荣强, 等. 一起诺如病毒致胃肠炎暴发疫情调查[J]. 江苏预防医学, 2012, 23(5):4-7. |

2015, Vol. 36

2015, Vol. 36